施肥对麦田土壤可溶性有机氮的影响

梁 斌,李俊良,杨学云,周建斌,3, *

1 青岛农业大学资源与环境学院,青岛 266109 2 西北农林科技大学资源环境学院,杨凌 712100 3 农业部西北植物营养与农业环境重点实验室,杨凌 712100

施肥对麦田土壤可溶性有机氮的影响

梁斌1,2,李俊良1,杨学云2,周建斌2,3, *

1 青岛农业大学资源与环境学院,青岛2661092 西北农林科技大学资源环境学院,杨凌7121003 农业部西北植物营养与农业环境重点实验室,杨凌712100

利用长期定位试验,研究施肥和小麦生长对土壤可溶性有机氮(EON)的影响。长期不同施肥土壤包括不施肥(No-F)、施用化肥(NPK)和有机肥与化肥配施(MNPK)3种。EON含量范围为7.5—29.3 kg/hm2,No-F、NPK和MNPK土壤中EON分别占可溶性总氮的40%、56%和56%。长期有机肥与化肥配施显著提高0—15 cm土层EON含量,但对30 cm以下土层EON含量无影响。在小麦开花期,可溶性有机氮的含量及其相对含量显著高于拔节期和收获期。虽然施用氮肥对当季EON含量无显著影响,但同位素示踪微区试验表明,土壤耕层(0—15 cm)中仍有0.4%—2.8%的可溶性有机氮来源于当季施入的肥料氮。可见,化学氮肥向可溶性有机氮的转化缓慢,但农田土壤中可溶性有机氮含量与矿质态氮含量相当,发生淋溶损失的风险大。

长期定位施肥试验;小麦生长期;淋溶;15N标记

土壤可溶性有机氮(Extractable organic N, EON)虽仅占土壤全氮的很小部分,但近年来的研究表明,它是土壤氮库中最活跃的组分之一,对土壤氮素循环影响很大[1]。在林地土壤中可溶性有机氮占可溶性总氮的比例可高达90%以上[2],土壤EON与土壤氮素迁移和供应的关系不可忽视[3]。可溶性有机氮含量与土壤氮素矿化和土壤微生物量氮显著相关[4],研究表明土壤不溶性有机氮向EON的转化是土壤中有机氮矿化的限制因子[3]。可溶性有机氮除了是土壤微生物氮素的重要来源之外[5],一些低分子量的EON可以直接或者通过菌根被植物吸收利用[3]。在一些降雨量大或灌溉地区,可溶性有机氮的淋溶损失是氮素损失的重要途径之一[6-7],在林地生态系统中EON是氮素损失的主要形态[8]。综上说明EON在土壤氮素组成、转化、供应和损失方面都具有重要的意义。

土壤可溶性有机氮含量及其行为易受土地利用方式、施肥状况和种植作物等因素影响。目前对农田土壤可溶性有机氮含量的影响因素研究相对较少,且得出的一些结果不尽一致。比如,Currie等[9]研究表明,施用化学氮肥提高土壤中EON含量,McDowell等[10]也得出类似的结论。但Vestgarden等[11]却发现,连续九年施用化学氮肥(每年30 kg/hm2)使土壤溶解性有机氮含量显著降低;Gundersen等[12]报告指出,施用氮肥并不影响溶解性有机氮的含量。因此,有必要进一步研究施肥对农田土壤中可溶性有机氮的影响。在林地中,可溶性有机氮是氮素损失的主要形态[8],那么在农田中可溶性有机氮的淋溶情况也是值得关注的问题。因为有机氮的淋溶不但关系到氮肥的利用状况,还可能带来一系列生态环境问题。

本研究利用已经进行了19a的田间试验,研究了长期不同施肥处理对麦田土壤耕层及0—100 cm剖面可溶性有机氮的影响以及短期内氮肥向可溶性有机氮转化情况,揭示施肥对土壤有机氮含量及其淋溶特性的影响,同时阐明了小麦不同生长阶段对土壤表层EON含量的影响,以期为完善土壤氮素循环理论、有效调控土壤氮素供应提供依据。

1 材料与方法

1.1试验设计

长期定位试验开始于1990年,种植制度为小麦单作,小麦收获后休闲至下季小麦种植。设对照(No-F,不施肥)、施用NPK化肥(NPK)、有机肥配施NPK化肥(MNPK)3个处理。其中氮肥为尿素,磷肥为过磷酸钙,钾肥为氯化钾。NPK处理施用量分别为N 135.0 kg/hm2、P 47.1 kg/hm2、K 56 kg/hm2。MNPK处理中过磷酸钙和氯化钾的施用量与NPK处理相同,氮肥用量与NPK处理相同,其中70%的氮来源于牛厩肥,30%的氮由尿素提供,各施肥处理的肥料均于小麦播种前一次性施用。小区面积为 399 m2(21 m×19 m)。土壤经19年不同施肥处理后其0—20 cm土层基本理化性状见表1。土壤质地为重壤土,土壤颗粒<0.002 mm、0.002—0.02 mm和 >0.02 mm的粘粒、粉粒和砂粒含量分别为168、516、316 g/kg。

2009年10月小麦种植施肥前,在每处理土壤内用PVC管设置氮同位素示踪微区试验,PVC管长63 cm,直径为24.5 cm,其中60 cm打入土中,3 cm留在地表之上。微区设施氮肥(+N)和不施氮肥(CK)两处理,重复3次,其中施入的氮肥为15N标记的尿素(丰度为19.58%)。在小麦种植前将所有处理土柱内0—15 cm土层土壤取出施入微区以外相同的磷、钾肥,在+N处理中按165 kg N/hm2的量加入标记尿素,CK处理不加氮肥,施肥后回填到原来PVC管中。于2009年10月18日播种,播种量为每PVC管30粒,小麦出苗后间苗至20株。

表1 长期不同施肥处理0—20 cm土层理化性状

以上数据为平均值(标准差)(n=3);同一行不同小写字母表示差异达显著水平

1.2土壤样品的采集

于小麦拔节期(2010年3月26日)、开花期(2010年5月4日)和收获期(2010年6月15日)在微区试验处理内采集土壤样品(0—15 cm),利用土钻在每土柱内采集混合样,过2 mm筛,测定其中可溶性总氮、矿质氮含量及其15N丰度。于小麦收获期在各长期定位试验处理中按10 cm一层采集0—100 cm土壤剖面样品,测定土壤剖面可溶性有机氮和矿质氮含量。

图1 小麦不同生长阶段土壤中(0—15 cm)来源于当季氮肥的可溶性有机氮百分比Fig.1 Percent of soil extractable organic N derived from 15N-labeled fertilizer in soils (0—15 cm) under long-term different fertilization managements during stem elongation (ET), flowering (FT), and harvest (HT) stage of wheat

1.3样品测定与数据分析

土壤样品采集过筛后,用0.5 mol/L硫酸钾浸提(土水比1∶4),浸提液中可溶性总氮用过硫酸钾氧化—紫外分光光度计比色法测定,矿质氮利用流动分析仪测定,可溶性有机氮含量为可溶性总氮和矿质氮含量之差,可溶性有机氮相对含量是指可溶性有机氮占可溶性总氮含量的百分比。微区试验处理中一部分土壤浸提液经过硫酸钾氧化后扩散[13],测定其中可溶性总氮的15N丰度,另一部分浸提液直接扩散,测定其中矿质态氮的15N丰度。扩散后的15N丰度用质谱仪测定,样品15N丰度测定由美国加利福尼亚大学戴维斯分校稳定同位素研究所完成。可溶性有机氮中的15N含量为可溶性总氮和矿质态氮中15N含量之差,来源于肥料的可溶性有机氮百分比用Ndff(%)表示,施入肥料向可溶性有机氮转化率用Con(%)表示,计算公式如下:

Ndff(%)=可溶性有机氮15N原子百分超/肥料15N丰度

(1)

Con(%)=可溶性有机氮含量×Ndff/施氮量

(2)

图表中的数据,用SAS Version 8.1 for Windows 作方差分析,若差异显著,采用LSD 法进行多重比较。

2 结果与分析

2.1施肥对土壤可溶性有机氮含量的影响

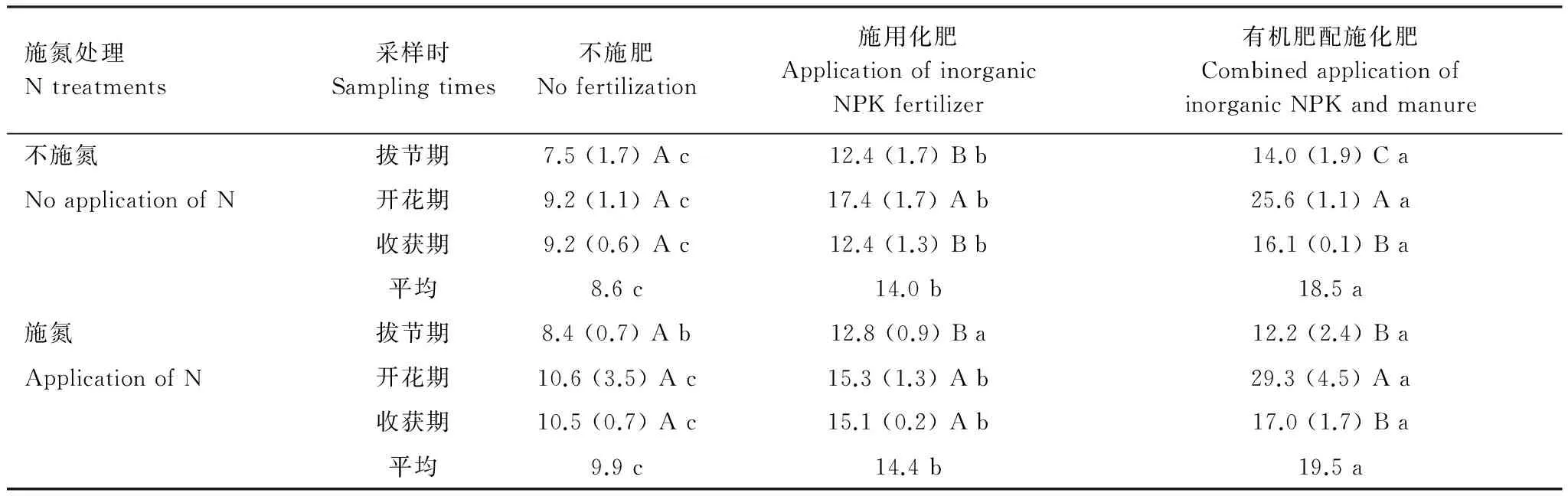

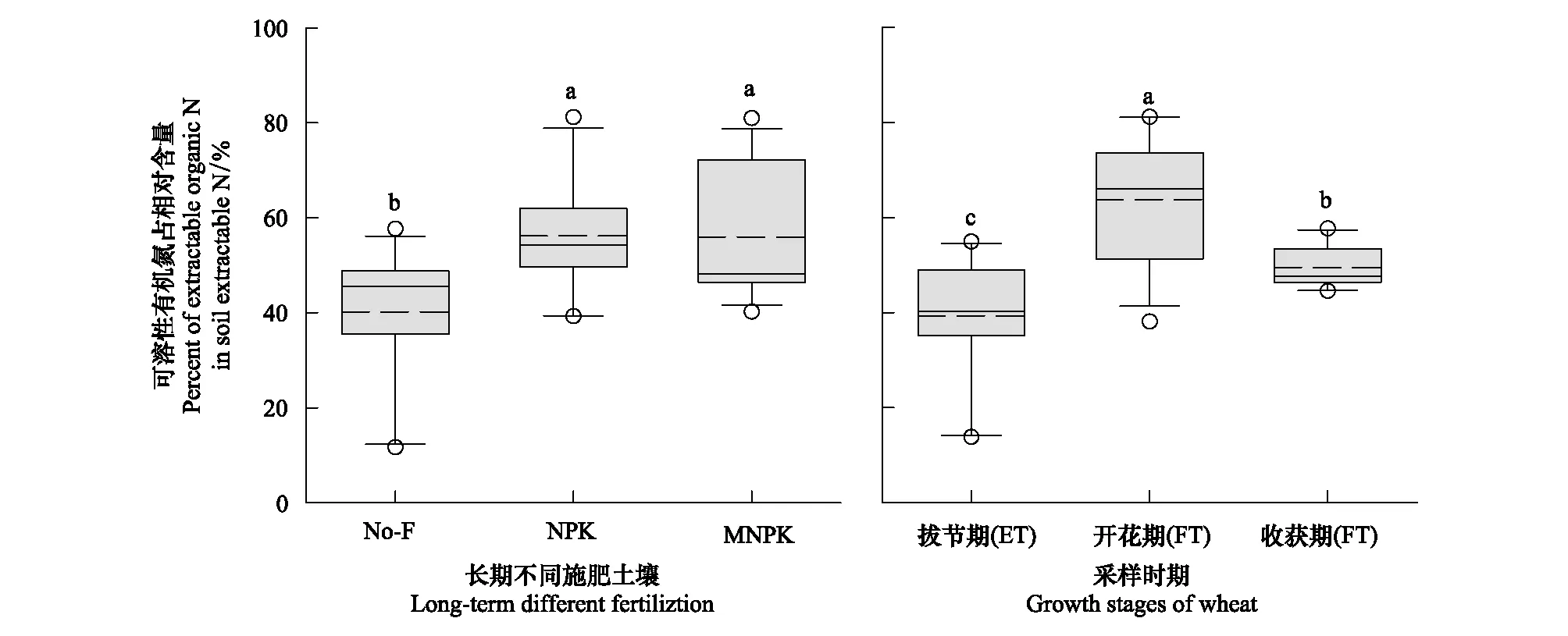

土壤可溶性有机氮的含量为7.5—29.3 kg/hm2(表2),占全氮的比例为0.6%—0.8%,其中来源于当季施入肥料氮的比例为0.5%—2.8%(图1),仅占施入氮肥的0.03%—0.24%。长期不同施肥显著影响EON含量(P< 0.01)(表3)。与No-F相比,长期施用化肥使EON显著增加34%—89%,平均增幅为55%(表2)。长期有机无机配施土壤可溶性有机氮含量范围为12.2—25.6 kg/hm2,平均为19.0 kg/hm2,显著高于NPK处理(表2)。MNPK和NPK土壤EON相对含量分别为40%—81%和39%—81%,平均皆为56%(图2)。No-F土壤可溶性有机氮的相对含量为40%,显著低于NPK和MNPK土壤(图2)。

表2土壤耕层(0—15 cm)可溶性有机氮含量(kg/hm2)

Table 2Soil extractable organic N content in 0—15 cm layer of soils under long-term different fertilization managements at different growth stage of wheat

施氮处理Ntreatments采样时Samplingtimes不施肥Nofertilization施用化肥ApplicationofinorganicNPKfertilizer有机肥配施化肥CombinedapplicationofinorganicNPKandmanure不施氮拔节期7.5(1.7)Ac12.4(1.7)Bb14.0(1.9)CaNoapplicationofN开花期9.2(1.1)Ac17.4(1.7)Ab25.6(1.1)Aa收获期9.2(0.6)Ac12.4(1.3)Bb16.1(0.1)Ba平均8.6c14.0b18.5a施氮拔节期8.4(0.7)Ab12.8(0.9)Ba12.2(2.4)BaApplicationofN开花期10.6(3.5)Ac15.3(1.3)Ab29.3(4.5)Aa收获期10.5(0.7)Ac15.1(0.2)Ab17.0(1.7)Ba平均9.9c14.4b19.5a

表中数据为平均值(标准差)(n=3); 同一行不同小写字母和同一列不同大写字母表示差异在0.05水平显著

表3 不同施肥和生长时期对土壤可溶性有机氮影响的F检验

2.2小麦不同生长阶段可溶性有机氮含量

3个采样时期中,开花期EON含量最高,此时期NPK和MNPK土壤EON含量较拔节期分别提高48%和82%。小麦生长对No-F土壤EON含量无显著影响(表2)。生长时期显著影响EON相对含量。小麦开花期可溶性有机氮相对含量最高,各处理范围为38%—81%,平均为64%;小麦收获期可溶性有机氮相对含量平均为50%;拔节期可溶性有机氮的相对含量最低,各处理平均为39%(图2)。

图2 长期不同施肥和小麦不同生长时期土壤耕层(0—15 cm)可溶性有机氮相对含量Fig.2 Effect of long-term fertilization and growth stage of wheat on percent of soil extractable organic N in soil extractable N

2.3可溶性有机氮在土壤0—100 cm剖面的分布

长期不同施肥主要影响0—30 cm土层EON含量,对30 cm以下土层EON含量影响不大(图3)。No-F、NPK和MNPK土壤CK处理0—100 cm土壤剖面EON累积量分别为43.1、51.6、55.2 kg/hm2(图4);MNPK和NPK土壤中EON累积量无显著差异,两者均显著高于No-F土壤。在种植前未施氮肥处理不同土壤40—100 cm累积的可溶性有机氮分别占可溶性总氮的43%—50%。种植前施用氮肥使土壤EON增加14%—34%,No-F、NPK和MNPK土壤分别达到58.1、67.2、63.2 kg/hm2(图4)。

图3 长期不同施肥土壤不施氮(a)和施氮(b)处理0—100 cm剖面可溶性有机氮含量Fig.3 Soil extractable organic N content in 0—100 cm layers of soils under long-term different fertilization managements

图4 长期不同施肥土壤可溶性有机氮在0—100 cm剖面的累积Fig.4 Accumulative soil extractable organic N in 0—100 cm layers of soils under long-term different fertilization managements

3 讨论

3.1土壤可溶性有机氮的含量

在本试验中,长期不同施肥土壤耕层EON含量为8—27 kg/hm2,No-F,NPK和MNPK 3种施肥处理的土壤EON占可溶性总氮的比例分别为13%—67%,38%—82%和44%—57%。Jensen等[14]研究表明,在沙土和沙壤土可溶性有机氮含量范围分别为:8—20、15—30 kg/hm2。Mcneill等[15]的研究中可溶性有机氮占可溶性总氮的比例为55%—66%。可见,农田土壤中可溶性有机氮含量与矿质态氮含量相当,是农田土壤中一个重要的氮库。

3.2长期不同施肥对土壤可溶性有机氮的影响

与长期施用化肥相比,长期有机肥配施化肥显著提高土壤EON含量以及可溶性有机氮占可溶性总氮的百分比,其他学者也得出相同的结论[26-27]。增加的可溶性有机氮一方面来源于施入的有机肥[28],另一方面来源于增加的作物根系脱落物等残体[18-19]。另外,长期有机无机配施土壤中微生物量氮是施用化肥土壤的1.3倍,微生物量的增加也可提高EON含量[25]。

3.3短期施用氮肥对土壤可溶性有机氮的影响

施入土壤的氮素除被作物吸收、微生物固持和损失外,还有一部分可在生物和非生物因素下转化为可溶性有机氮。在林地酸性土壤中,Dail等[29]研究指出,在对照、辐射灭菌和高温灭菌土壤中分别大约有30%、40%和55%所加入的硝态氮转化为土壤可溶性有机氮。Compton等[30]和Perakis等[31]也得出,硝态氮加入土壤之后,有很大一部分迅速地转化为土壤可溶性有机氮。Davidson等[32]研究发现,硝态氮加入土壤之后,在铁锰等化合物的作用下转化为亚硝态氮,而亚硝态氮与土壤有机物结合转化为可溶性有机氮。但其他学者[33-34]通过试验,并没有发现大量硝态氮向可溶性有机氮的转化。在本研究中,各小麦生长时期各土壤中有0.5%—2.8%的可溶性有机氮来源于当季施用的肥料氮,占当季施入氮肥的0.5%以下。说明化学氮肥向可溶性有机氮的转化比较缓慢,没有发生快速大量转化的情况。肥料氮在施肥当季转化为土壤可溶性有机氮的机理包括:(1)在肥料氮施入土壤之后,通过土壤微生物的固持与转化,部分肥料氮以可溶性有机氮的形态释放到土壤中[1];(2)施入的肥料氮可通过作物吸收及其分泌分泌物转化为土壤可溶性有机氮[35]。

3.4小麦生长阶段对土壤可溶性有机氮的影响

作物的生长对土壤可溶性有机氮含量有显著的影响[36]。本研究中,在小麦开花期土壤可溶性有机氮含量和占可溶性有机氮的比例皆为最高。这说明旺盛生长的作物增加土壤可溶性有机氮的含量,其他学者也得出相同的结论[37-38]。这是因为在旺盛生长阶段,作物根系、根系脱落物和土壤微生物量都较高所致。研究表明,在作物开花期根系脱落物的碳可达根系碳含量的两倍[39]。一方面,根系的分泌物及脱落物本身含有大量的可溶性有机氮;另一方面,较多的有机碳为土壤微生物提供了大量的能源物质,从而增加了土壤微生物的数量,而微生物数量与土壤可溶性有机氮含量呈显著正相关关系[20,37]。

3.5可溶性有机氮在土壤剖面的分布

长期有机肥配施化肥显著提高0—15 cm土层可溶性有机氮含量,但对20 cm以下土壤可溶性有机氮含量无影响,MNPK土壤40—100 cm剖面中累积的EON与No-F和NPK土壤相当。说明长期有机肥配施化肥仅增加土壤耕层可溶性有机氮含量。但Dyke等[40]指出,与单施化肥相比,施用有机肥使更多的可溶性有机氮淋溶到土壤下层。结果不同的原因可能与Dyke等[40]的研究中有机肥的施用量更高(每年有机肥提供的氮量为240 kg/hm2)和试验进行的时间更长(156a)有关。在种植前未施氮肥处理不同土壤40—100 cm累积的可溶性有机氮分别占可溶性总氮的43%—50%。Madou等[41]研究表明,土壤中通过淋溶损失的氮素中土壤可溶性有机氮占17%—32%,说明可溶性有机氮的淋溶损失是氮素损失的重要途径之一。Van Kessel等[7]也报道指出,可溶性有机氮是农田土壤中氮素淋溶损失的重要形态,尤其是在降雨量氮或灌溉地区。因此,在评价农田氮素淋溶损失时,应该考虑可溶性有机氮的损失。

[1]Haynes R J. Labile organic matter fractions as central components of the quality of agricultural soils: An overview. Advances in Agronomy, 2005, 85: 221-268.

[2]Hannam K D, Prescott C E. Soluble organic nitrogen in forests and adjacent clearcuts in British Columbia, Canada. Canadian Journal of Forest Research, 2003, 33(9): 1709-1718.

[3]Jones D L, Shannon D, V Murphy D, Farrar J. Role of dissolved organic nitrogen (DON) in soil N cycling in grassland soils. Soil Biology and Biochemistry, 2004, 36(5): 749-756.

[4]Zhong Z K, Makeschin F. Soluble organic nitrogen in temperate forest soils. Soil Biology and Biochemistry, 2003, 35(2): 333-338.

[5]Hart S C, Nason G E, Myrold D D, Perry D A. Dynamics of gross nitrogen transformation in an old-growth forest: the carbon connection. Ecology, 1994, 75(4): 880-891.

[6]张宏威, 康凌云, 梁斌, 陈清, 李俊良, 严正娟. 长期大量施肥增加设施菜田土壤可溶性有机氮淋溶风险. 农业工程学报, 2013, 29(21): 99-107.

[7]Van Kessel C, Clough T, van Groenigen J W. Dissolved organic nitrogen: an overlooked pathway of nitrogen loss from agricultural systems?. Journal Of Environmental Quality, 2009, 38(2): 393-401.

[8]Smolander A, Kitunen V, Mälkönen E. Dissolved soil organic nitrogen and carbon in a Norway spruce stand and an adjacent clear-cut. Biology and Fertility of Soils, 2001, 33(3): 190-196.

[9]Currie W S, Aber J D, McDowell W H, Boone R D, Magill A H. Vertical transport of dissolved organic C and N under long-term N amendments in pine and hardwood forests. Biogeochemistry, 1996, 35(3): 471-505.

[10]McDowell W H, Currie W S, Aber J D, Yano Y. Effects of chronic nitrogen amendments on production of dissolved organic carbon and nitrogen in forest soils. Water, Air, and Soil Pollution, 1998, 105(1/2): 175-182.

[11]Vestgarden L, Abrhamsen G, Stuanes A O. Soil solution response to nitrogen and magnesium application in a Scots pine forest. Soil Science Society of America Journal, 2001, 65(6): 1812-1823.

[12]Gundersen P, Callesen I, De Vries W. Nitrate leaching in forest ecosystems is related to forest floor C/N ratios. Environmental Pollution, 1998, 102(1): 403-407.

[14]Jensen L S, Mueller T, Magid J, Nielsen N E. Temporal variation of C and N mineralization, microbial biomass and extractable organic pools in soil after oilseed rape straw incorporation in the field. Soil Biology and Biochemistry, 1997, 29(7): 1043-1055.

[15]McNeill A M, Sparling G P, Murphy D V, Braunberger P, Fillery I R P. Changes in extractable and microbial C, N, and P in a Western Australian wheatbelt soil following simulated summer rainfall. Australian Journal of Soil Research, 1998, 36(5): 841-854.

[16]Fang Y T, Zhu W X, Gundersen P, Mo J M, Zhou G Y, Yoh M. Large loss of dissolved organic nitrogen from nitrogen-saturated forests in subtropical China. Ecosystems, 2009, 12(1): 33-45.

[17]Dijkstra F A, West J B, Hobbie S E, Reich P B, Trost J. Plant diversity, CO2, and N influence inorganic and organic N leaching in grasslands. Ecology, 2007, 88(2): 490-500.

[18]Embacher A, Zsolnay A, Gattinger A, Munch J C. The dynamics of water extractable organic matter (WEOM) in common arable topsoils: II. Influence of mineral and combined mineral and manure fertilization in a Haplic Chernozem. Geoderma, 2008, 148(1): 63-69.

[19]丛日环. 小麦-玉米轮作体系长期施肥下农田土壤碳氮相互作用关系研究 [D]. 北京: 中国农业科学院, 2012.

[21]Zhong W H, Cai Z C, Zhang H. Effects of long-term application of inorganic fertilizers on biochemical properties of a rice-planting red soil. Pedosphere, 2007, 17(4): 419-428.

[22]葛体达, 唐东梅, 宋世威, 黄丹枫. 不同园艺生产系统土壤可溶性有机氮差异. 应用生态学报, 2009, 20(2): 331-336.

[23]Zak D R, Pregitzer K S, Burton A J, Edwards I P, Kellner H. Microbial responses to a changing environment: implications for the future functioning of terrestrial ecosystems. Fungal Ecology, 2011, 4(6): 386-395.

[24]McDowell W H, Magill A H, Aitkenhead-Peterson J A, Aber J D, Merriam J L, Kaushal S S. Effects of chronic nitrogen amendment on dissolved organic matter and inorganic nitrogen in soil solution. Forest Ecology and Management, 2004, 196(1): 29-41.

[25]Liang B, Yang X Y, Murphy D V, He X H, Zhou J B. Fate of 15 N-labeled fertilizer in soils under dryland agriculture after 19 years of different fertilizations. Biology and Fertility of Soils, 2013, 49(8): 977-986.

[26]Ros G H, Hoffland E, van Kessel C, Temminghoff E J M. Extractable and dissolved soil organic nitrogen---A quantitative assessment. Soil Biology and Biochemistry, 2009, 41(6): 1029-1039.

[27]宋震震, 李絮花, 李娟, 林治安, 赵秉强. 有机肥和化肥长期施用对土壤活性有机氮组分及酶活性的影响. 植物营养与肥料学报, 2014, 20(3): 525-533.

[28]赵满兴, 周建斌, 陈竹君, 杨绒. 有机肥中可溶性有机碳、氮含量及其特性. 生态学报, 2007, 27(1): 297-403.

[29]Dail D B, Davidson E A, Chorover J. Rapid abiotic transformation of nitrate in an acid forest soil. Biogeochemistry, 2001, 54(2): 131-146.

[30]Compton J E, Boone R D. Soil nitrogen transformations and the role of light fraction organic matter in forest soils. Soil Biology and Biochemistry, 2002, 34(7): 933-943.

[31]Perakis S S, Hedin L O. Fluxes and fates of nitrogen in soil of an unpolluted old-growth temperate forest, southern Chile. Ecology, 2001, 82(8): 2245-2260.

[32]Davidson E A, Chorover J, Dail D B. A mechanism of abiotic immobilization of nitrate in forest ecosystems: the ferrous wheel hypothesis. Global Change Biology, 2003, 9(2): 228-236.

[33]Colman B P, Fierer N, Schimel J P. Abiotic nitrate incorporation, anaerobic microsites, and the ferrous wheel. Biogeochemistry, 2008, 91(2/3): 223-227.

[34]Davidson E A, Dail D B, Chorover J. Iron interference in the quantification of nitrate in soil extracts and its effect on hypothesized abiotic immobilization of nitrate. Biogeochemistry, 2008, 90(1): 65-73.

[35]Zsolnay A. Dissolved organic matter: artefacts, definitions, and functions. Geoderma, 2003, 113(3/4): 187-209.

[36]Murphy D V, Macdonald A J, Stockdale E A, Goulding K W T, Fortune S, Gaunt J L, Poulton P R, Wakefield J A, Webster C P, Wilmer W S. Soluble organic nitrogen in agricultural soils. Biology and Fertility of Soils, 2000, 30(5/6): 374-387.

[37]Liang B, Yang X Y, He X H, Zhou J B. Effects of 17-year fertilization on soil microbial biomass C and N and soluble organic C and N in loessial soil during maize growth. Biology and Fertility of Soils, 2011, 47(2): 121-128.

[38]Murphy D V, Stockdale E A, Poulton P R, Willison T W, Goulding K W T. Seasonal dynamics of carbon and nitrogen pools and fluxes under continuous arable and ley-arable rotations in a temperate environment. European Journal of Soil Science, 2007, 58(6): 1410-1424.

[39]Amos B, Walters D T. Maize root biomass and net rhizodeposited carbon: an analysis of the literature. Soil Science Society of America Journal, 2006, 70(5): 1489-1503.

[40]Dyke G V, George B J, Johnston A E, Poulton P R, Todd A D. The Broadbalk Wheat Experiment 1968—1978: yields and plant nutrients in crops grown continuously and in rotation//Rothamsted Experimental Station Report for 1982, part 2. Harpenden: Rothamsted Experimental Station,. 1983: 5-44.

[41]Madou M C, Haynes R J. Soluble organic matter and microbial biomass C and N in soils under pasture and arable management and the leaching of organic C, N and nitrate in a lysimeter study. Applied Soil Ecology, 2006, 34(2/3): 160-167.

Effect of fertilization on extractable organic nitrogen in wheat monoculture cropping systems

LIANG Bin1,2, LI Junliang1, YANG Xueyun2, ZHOU Jianbin2,3,*

1CollegeofResourcesandEnvironmentalSciences,QingdaoAgricultureUniversity,Qingdao266109,China2CollegeofResourcesandEnvironmentalSciences,NorthwestAgricultureandForestryUniversity,Yangling712100,China3KeyLaboratoryofPlantNutritionandtheAgri-EnvironmentinNorthwestChina,MinistryofAgriculture,Yangling712100,China

Soil extractable organic nitrogen (SON) is an important nutrient pool involved in N transformations, and the content and conversion of SON are affected by fertilization practices. However, many gaps remain in our understanding of SON, especially in agricultural soil. The effects of long-term (1990—2009) fertilization on SON at elongation, flowering, and harvest stages in wheat were evaluated in a loess soil (Eum-Orthic Anthrosol) in northwestern China. The treatments included no fertilization (No-F), application of inorganic NPK fertilizer (NPK), and combined application of inorganic NPK and manure (MNPK). Using15N tracer techniques,15N-labeled urea (165 kg N/hm2) was applied to microplots within each treatment to investigate the effect of short-term addition of N on content of SON during the wheat-growing season in wheat monoculture cropping systems. The SON content was 7.5—29.3 kg/hm2and accounted for 40%, 56%, and 56% of total extractable N in No-F, NPK, and MNPK, respectively. Compared with No-F, application of inorganic NPK fertilizer increased SON content significantly (55% on average) in the 0—15 cm soil layer. Soil extractable organic N content in the MNPK treatment was significantly higher (by 32%—35%) than that in the NPK treatment in the 0—15 cm layer. Long-term fertilization had no effect on SON content below 30 cm. SON was highest at flowering and was significantly higher during flowering than at the elongation stage in NPK and MNPK (by 48% and 82%, respectively). In relation to No-F, fertilization treatments increased the SON significantly in the 0—100 cm soil profile, SON was 43.1, 51.6, 55.2 kg/hm2in No-F, NPK, and MNPK, respectively. Addition of N had no significant effect on SON content in the 0—15 cm soil layer during the same growing season; however, 0.4%—2.8% of SON was derived from the15N-labeled fertilizer applied before seeding, representing 0.03%—0.24% of the fertilizer, and short-term addition of N increased SON in the 0—100 cm soil profile by 35%, 30%, and 14% in No-F, NPK, and MNPK, respectively. We conclude that the conversion of inorganic N to extractable organic N was slow. However, long-term fertilization increased SON content in the topsoil, and SON is a significant nitrogen pool in agriculture soils.

long-term fertilization; wheat growth stage; leaching;15N labeling

国家自然科学基金资助项目(31372137, 31401947)

2014-12-12; 网络出版日期:2015-10-30

Corresponding author.E-mail: jbzhou@nwsuaf.edu.cn

10.5846/stxb201412122482

梁斌,李俊良,杨学云,周建斌.施肥对麦田土壤可溶性有机氮的影响.生态学报,2016,36(14):4430-4437.

Liang B, Li J L, Yang X Y, Zhou J B.Effect of fertilization on extractable organic nitrogen in wheat monoculture cropping systems.Acta Ecologica Sinica,2016,36(14):4430-4437.