Outcome Trials in the Therapeutic Management of Hypertension in East Asians

Ji-Guang Wang and Yan Li

Introduction

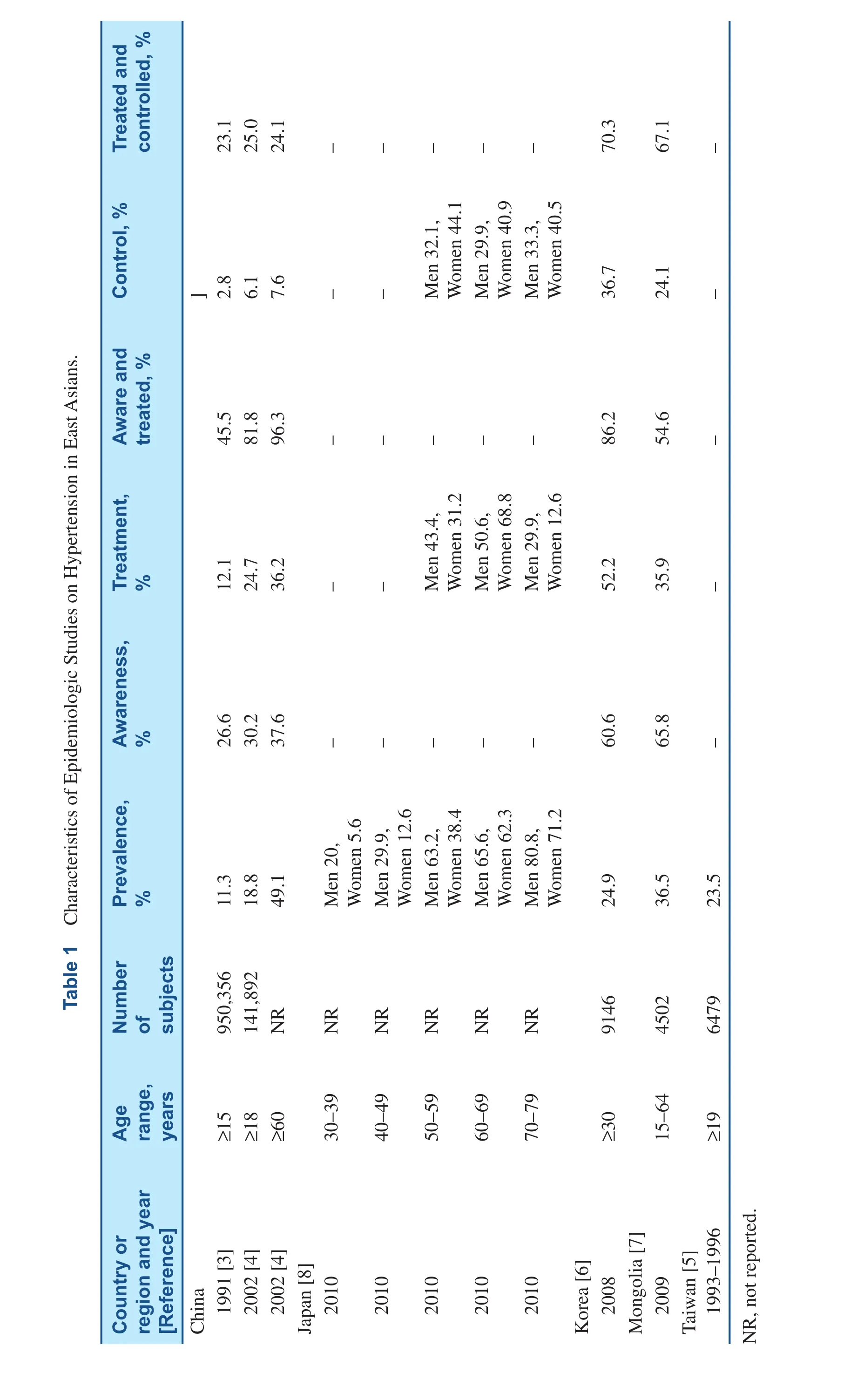

After World War II, the prevalence of hyper tension in East Asians increased substantially in most countries and regions. Taking China as an example, the prevalence of hypertension increased from less than 10% before 1980 [1, 2] to approximately 25% in the latest nationwide survey in 2012 [3, 4]. This increase can to some extent be attributable to the increased number of elderly people over the years.However, Westernized lifestyle characterized by high salt, high fat, high sugar and high calorie diet and physical inactivity could be a major risk factor for the increasing prevalence of hypertension in these populations. If the most recent data in East Asians is compared across countries or regions, the prevalence of hypertension ranged from about 25%in Chinese living either in the mainland [4] or in Taiwan [5] and Koreans [6], to approximately 40%in Mongolians [7] (Table 1). The overall prevalence of hypertension was not reported in the most recent Japanese national blood pressure survey in 2010.The age-specific data suggested that the prevalence of hypertension in Japanese was high [8]. The prevalence of hypertension in persons of 60–69 years was more than 60% in both men and women [8],much higher than the 49.1% prevalence in Chinese of 60 years or older in 2002 [4].

There is not much high quality data on the management of hypertension except for the national blood pressure surveys in China [4] and Korea [6].According to the currently available data, Koreans[6] and Japanese [8] seemed to have higher awareness, treatment and control rates of hypertension than other East Asian populations [4, 5, 7] (Table 1).The control rate of hypertension was about 35% in Koreans [6] and Japanese [8], 24% in Mongolians[7], and less than 10% in Chinese [4]. Nevertheless,several classes of efficacious antihypertensive drugs are readily available for the management of hypertension in most countries or regions. In the past several decades, several outcome trials on the therapeutic management of hypertension were conducted in East Asians. This review article summarizes the literature of outcome trials on hypertension in this region.

Placebo-Controlled Trials

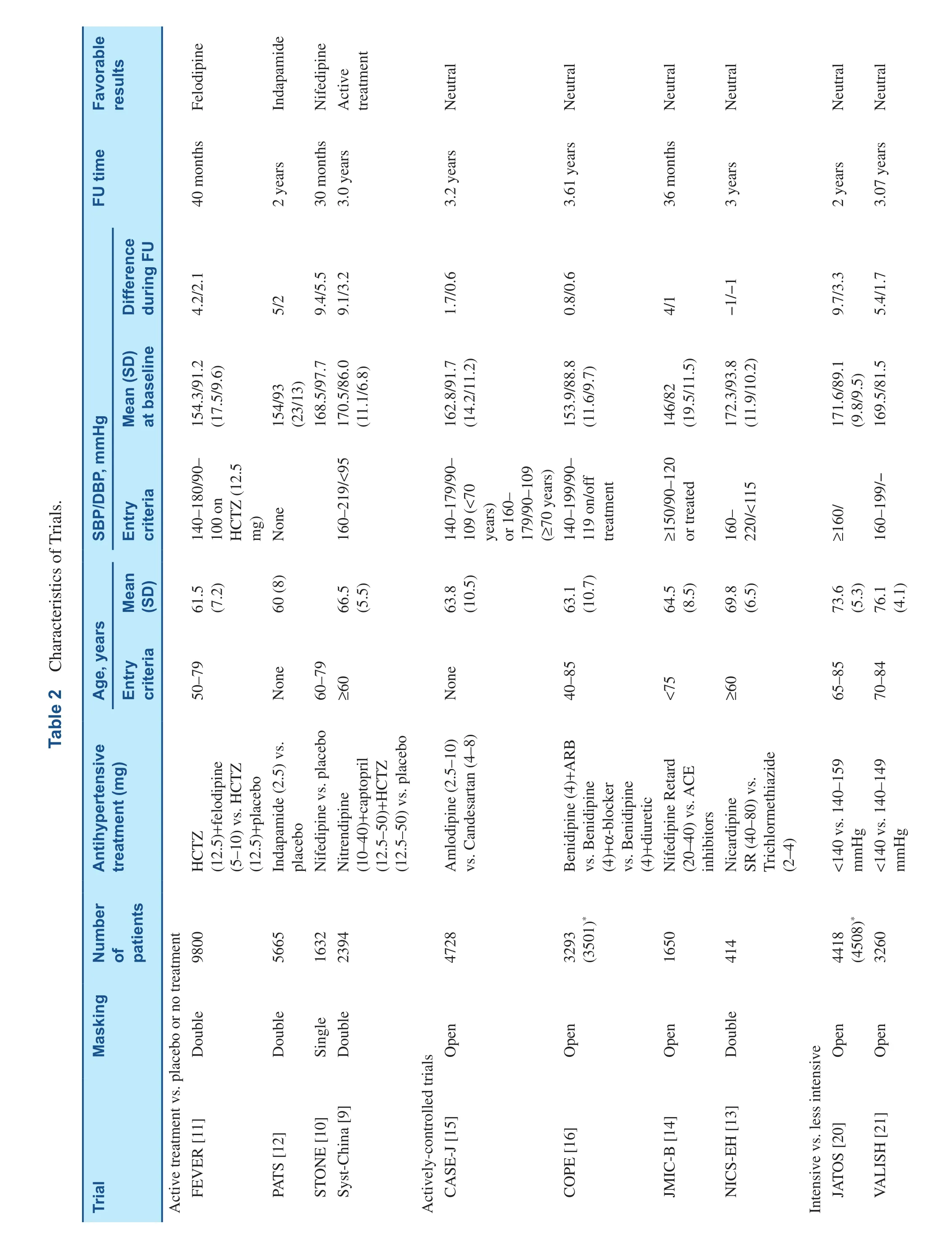

Since the late 1980s, several placebo-controlled outcome trials were conducted in China to investigate whether antihypertensive therapy would prevent cardiovascular complications in hypertensive patients (Table 2) [9–12].

The Systolic Hypertension in China (Syst-China)trial investigated whether active antihypertensive treatment would prevent fatal and non-fatal stroke in 2394 elderly (≥60 years) patients with isolated systolic hypertension (systolic blood pressure ≥160 mmHg and diastolic blood pressure <95 mmHg).Active antihypertensive treatment was initiated by nitrendipine, with the possible addition of captopril and hydrochlorothiazide, to achieve the goal systolic blood pressure of 150 mmHg or lower. At 2 years of follow-up, active treatment (n=1253),compared with placebo (n=1141), reduced systolic/diastolic blood pressure by 9.1/3.2 mmHg. During a median follow-up of 3 years, active treatment reduced the incidence rate of fatal and non-fatal stroke by 38%. Active treatment also signi ficantly reduced all-cause mortality, cardiovascular mortality, stroke mortality, and all fatal and non-fatal cardiovascular endpoints by 39%, 39%, 58%, and 37%, respectively [9].

The Shanghai Trial of Nifedipine in the Elderly(STONE) was a single-blind study in 1632 elderly(60–79 years) patients with hypertension (systolic blood pressure 160–219 mmHg or diastolic blood pressure 96–124 mmHg), alternately allocated to either nifedipine (n=817) or placebo (n=815).During a mean follow-up of 30 months, nifedipine treatment reduced systolic/diastolic blood pressure by 9.3/5.5 mmHg, and the incidence of fatal and non-fatal stroke by 58%. Nifedipine also signi fi-cantly reduced the incidence of all fatal and nonfatal cardiovascular events by 60% [10].

The Felodipine Event Reduction (FEVER)trial compared felodipine (5 mg daily) with placebo in 9800 patients (50–79 years of age) with a systolic/ diastolic blood pressure in the range of 140–180/90–100 mmHg after 6 weeks of treatment with hydrochlorothiazide 12.5 mg per day. During a mean follow-up of 3.3 years, felodipine, compared with placebo reduced systolic/diastolic blood pressure by 4.2/2.1 mmHg, and the primary endpoint(fatal and non-fatal stroke) by 27%. Felodipine also signi ficantly reduced all cardiovascular events, all cardiac events, all-cause mortality, coronary events,heart failure, cardiovascular death, and cancer by 27%, 35%, 31%, 32%, 30%, 33%, and 36%, respectively [11].

The Post-stroke Antihypertensive Treatment Study(PATS) was a double-blind blood pressure lowering trial with indapamide (2.5 mg daily) in hypertensive and non-hypertensive patients with a history of stroke or transient ischemic attack. During a median follow-up of 2 years, indapamide reduced systolic/diastolic blood pressure by 5/2 mmHg, and the incidence of recurrent stroke by 29%. Indapamide also signi ficantly reduced the incidence of all fatal and non-fatal cardiovascular endpoints by 23% [12].

Actively-Controlled Trials

Since the 1990s, several actively-controlled outcome trials were conducted in Japan to compare various classes or combinations of antihypertensive drugs as initial therapy for the prevention of cardiovascular complications (Table 2) [13–16]. All these trials had an open design, except for the doubledummy National Intervention Cooperative Study in Elderly Hypertensives (NICS-EH) [13], and had a relatively small sample size in the detection of a modest or moderate difference between antihypertensive drug classes.

?

?

NICS-EH compared two outdated antihypertensive drugs (sustained-release nicardipine [n=204]versus trichlormethiazide [n=210]) in 414 elderly(≥60 years) patients with hypertension (systolic blood pressure 160–220 mmHg and diastolic blood pressure <115 mmHg). During 5 years of follow-up,nicardipine was slightly less efficacious than trichlormethiazide in lowering systolic/diastolic blood pressure (−1/−1 mmHg). During follow-up, a total of 39 events occurred in the two groups combined,and no signi ficant difference was observed in any outcome between the two treatment groups [13].

The Japan Multicenter Investigation for Cardiovascular Diseases-B (JMIC-B) trial compared nifedipine retard with angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitors (enalapril 5–10 mg, imidapril 5–10 mg, or lisinopril 10–20 mg, once daily)in 1650 patients with both hypertension and coronary heart disease, diagnosed according to coronary angiography (stenosis ≥75%), a history of angina pectoris (>2 episodes per week), or ST-segment depression of at least 1 mm during the treadmill exercise test. During a mean follow-up of 36 months, blood pressure reductions were greater in the nifedipine group than the ACE inhibitors group(−4/−1 mmHg). The incidence rate of the primary endpoint (cardiac events: cardiac death or sudden death, myocardial infarction, hospitalization for angina pectoris or heart failure, serious arrhythmia, and coronary interventions) was similar in the nifedipine (116 events, 14.0%) and ACE inhibitors(106 events, 12.9%) groups (+5%; P=0.75) [14].

The Candesartan Antihypertensive Survival Evaluation in Japan (CASE-J) trial compared amlodipine- with candesartan-based antihypertensive regimens in 4728 high risk hypertensive patients. To achieve the goal blood pressure of 140/90 mmHg or below, diuretics, α-blockers, β-blockers, and/or αβ-blockers could be added. During a mean follow-up of 3.2 years, systolic/diastolic blood pressures were 1.7/0.6 mmHg lower in the amlodipine group than the candesartan group, even though more patients in the candesartan group required addition of other antihypertensive drugs (54.5% vs. 42.7%;P<0.0001). The incidence rates of the primary (sudden death and cerebrovascular, cardiac, renal, and vascular events) and secondary endpoints were not statistically different between the two treatment groups. The risk of stroke was slightly but nonsigni ficantly lower in the amlodipine group than the candesartan group (−23%; P=0.28) [15].

?

The Combination Therapy of Hypertension to Prevent Cardiovascular Events (COPE) trial was designed to compare three combinations of antihypertensive drugs in the prevention of cardiovascular events in 3501 patients of 40–85 years old and with uncontrolled hypertension (systolic/diastolic blood pressure ≥140/90 mmHg) by the calcium channel blocker benidipine 4 mg/day. Patients were randomly assigned to receive angiotensin receptor blocker (n=1167), β-blocker (n=1166), or thiazide diuretic (n=1168) in addition to benidipine. During a median follow-up of 3.61 years, blood pressure was reduced similarly in the three groups, with a control rate of 64.1%, 66.9%, and 66.0% at the end of treatment in the benidipine–angiotensin receptor blocker, benidipine–β-blocker, and benidipine–thiazide groups, respectively. The cardiovascular composite endpoint occurred in 41 (3.7%), 48 (4.4%),and 32 (2.9%) patients, respectively, with a hazard ratio of 1.26 (P=0.35) in the benidipine–angiotensin receptor blocker and 1.54 (P=0.06) in the benidipine–β-blocker groups compared with the benidipine–thiazide group [16].

None of these trials had sufficient power to detect a modest or moderate but clinically relevant difference between various classes of antihypertensive drugs. However, if the results of these trials were pooled with that of studies in other populations, there could be signi ficant difference between different drug classes. For instance, if the CASE-J trial [15]was combined with the Valsartan Antihypertensive Long-term Use Evaluation (VALUE) [17] and Irbesartan Diabetic Nephropathy Trial (IDNT)[18] trials that also compared amlodipine with an angiotensin receptor blocker, amlodipine provided superior protection against stroke and myocardial infarction by 16% and 17%, respectively [19].

Intensive Versus Less Intensive Blood Pressure Control

Two Japanese trials compared intensive with less intensive blood pressure control in elderly hypertensive patients [20, 21]. These two trials again had a relatively small sample size and hence inadequate power in the detection of a modest or moderate difference between different levels of blood pressure control.

The Japanese Trial to Assess Optimal Systolic Blood Pressure in Elderly Hypertensive Patients(JATOS) compared the 2-year effect of intensive(systolic blood pressure <140 mmHg, n=2212) versus less intensive treatment (systolic blood pressure 140–159 mmHg, n=2206) in 4418 elderly (65–85 years) patients with essential hypertension (pretreatment systolic blood pressure ≥160 mmHg).The first line drug was a long-acting calcium channel blocker, efonidipine. At last clinic visit, systolic/diastolic blood pressures were signi ficantly lower in the intensive than the less intensive treatment group(135.9/74.8 vs. 145.6/78.1 mmHg), with a between group difference of 9.7/3.3 mmHg. However, no signi ficant difference between the two treatment groups was observed for the incidence of the primary endpoint (combination of cardiovascular disease and renal failure, 86 patients in each group; P=0.99)and for total mortality (54 in the intensive-treatment group vs. 42 in the less intensive-treatment group,P=0.22). In a post-hoc analysis, however, there was interaction between age and treatment for the primary endpoint (P=0.03). Intensive blood pressure control tended to confer bene fit in younger elderly(65–74 years) but harm in older elderly (≥75 years)[20].

The Valsartan in Elderly Isolated Systolic Hypertension (VALISH) Study compared intensive (systolic blood pressure ≤140 mmHg, n=1545)with less intensive blood pressure control (systolic blood pressure 140–150 mmHg, n=1534) in the prevention of cardiovascular mortality and morbidity in 3260 elderly (70–84 years) patients with isolated systolic hypertension (systolic blood pressure 160–199 mmHg). At baseline, age averaged 76.1 years, and systolic/diastolic blood pressures were 169.5/81.5 mmHg. At 3 years of follow-up,systolic/diastolic blood pressures were 136.6/74.8 mmHg and 142.0/76.5 mmHg, respectively, with a between-group difference of 5.4/1.7 mmHg. During a median follow-up of 3.07 years, the overall rate of the primary composite endpoint was slightly lower in the intensive (10.6/1000 patient-years)than the less intensive blood pressure control group(12.0/1000 patient-years, hazard ratio 0.89; 95%CI 0.60–1.34; P=0.38). However, none of the differences between the two groups reached statistical signi ficance for any outcome [21].

Subgroups of Multinational Trials

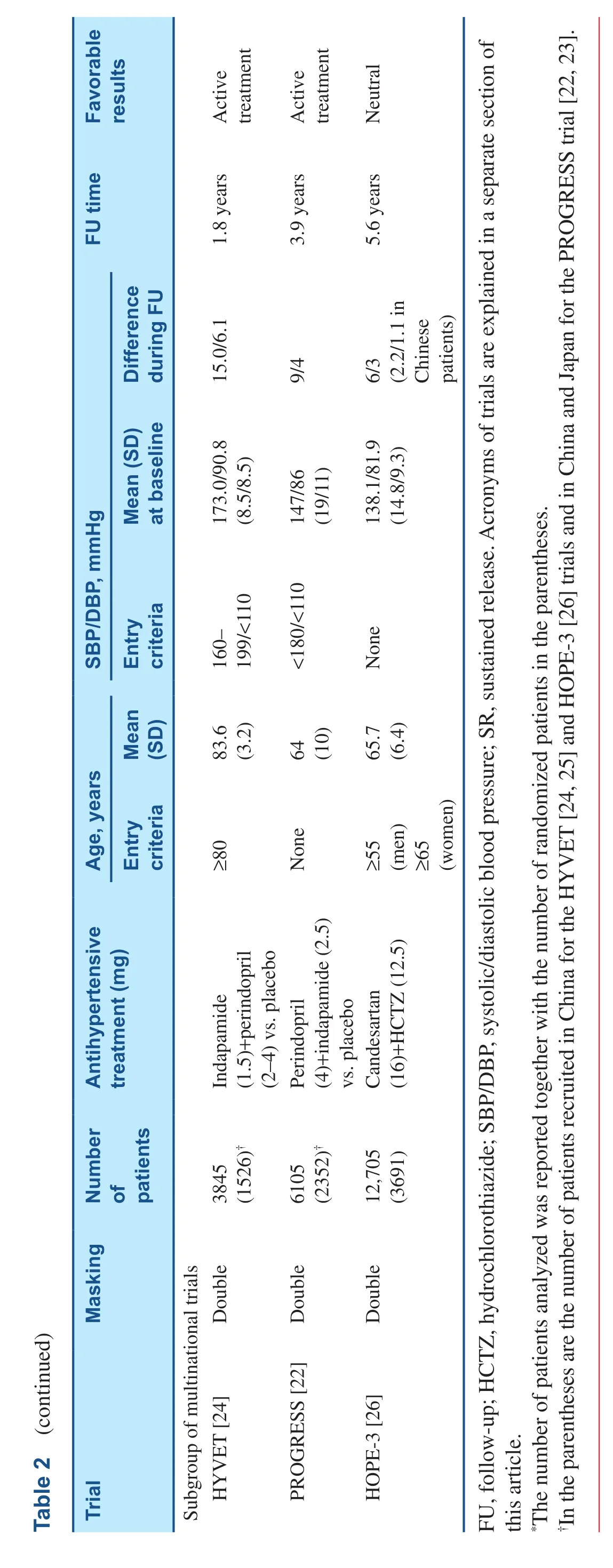

Since the 1990s, several multinational trials in blood pressure lowering treatment involved East Asians, such as the perindopril PROtection aGainst REcurrent Stroke Study (PROGRESS) [22, 23], the HYpertension in the Very Elderly Trial (HYVET)[24, 25], and the Heart Outcomes Prevention Evaluation-3 (HOPE-3) trial [26].

The PROGRESS trial was designed to determine the effects of a blood-pressure lowering regimen in 6105 hypertensive and non-hypertensive patients with a history of stroke or transient ischemic attack,recruited from 172 centers in Asia, Australasia, and Europe. Over 4 years of follow-up, active treatment(perindopril 4 mg daily with the possible addition of indapamide, n=3051), compared with placebo(n=3054), reduced blood pressure by 9/4 mmHg,and the incidence of fatal and non-fatal stroke by 28%. Active treatment also signi ficantly reduced the risk of total major vascular events by 26% [22].Of particular note, the PROGRESS trial included 2335 Asians, either Chinese or Japanese. Active treatment reduced systolic/diastolic blood pressure by 10.3/4.6 mmHg in Asians and by 8.1/3.6 mmHg in Western participants. The risk reduction tended to be greater in Asians for stroke (39% vs. 22%, P for homogeneity=0.10) and major vascular events(38% vs. 20%, P for homogeneity=0.06) [23].

The HYVET trial investigated whether antihypertensive treatment would reduce the risk of stroke in 3845 very elderly (≥80 years) patients with hypertension (systolic blood pressure ≥160 mmHg and diastolic blood pressure <110 mmHg), recruited from Australasia, China, Europe, and Tunisia.Active treatment was started by indapamide (sustained release, 1.5 mg) with the possible addition of perindopril 2 or 4 mg. At 2 years of follow-up,active treatment (n=1933), compared with placebo(n=1912), reduced systolic/diastolic blood pressure by 15.0/6.1 mmHg. During a median follow-up of 1.8 years, active treatment reduced the incidence of fatal and non-fatal stroke by 30%, stroke mortality by 39%, all-cause mortality by 21%, cardiovascular mortality by 23%, and heart failure by 64% [24]. The HYVET trial included 1526 patients from China.Although the outcome results in Chinese were not published separately, the overall results should apply for Chinese people of 80 years or older [25].

The recently published HOPE-3 trial was a 2×2 factorial study for blood pressure and lipid-lowering treatments in 12,705 patients at intermediate cardiovascular risk. There was no threshold of blood pressure for inclusion into the trial. Mean systolic/diastolic blood pressures at baseline were 138.1/81.9 mmHg. Over a median follow-up of 5.6 years, active antihypertensive treatment with a single-pill combination of candesartan 16 mg/hydrochlorothiazide 12.5 mg per day, compared with placebo, reduced systolic/diastolic blood pressures by 6/3 mmHg, but did not in fluence either the risk of the two co-primary endpoints (cardiovascular mortality, stroke, and myocardial infarction without[de finition 1] or with [de finition 2] cardiac arrest,congestive heart failure and revascularization) or the risk of any secondary endpoint. Nonetheless, a posthoc analysis suggested that active antihypertensive treatment signi ficantly reduced the risk of both coprimary outcomes 1 and 2 by 27% and 24%, respectively, in the top tertile of baseline systolic blood pressure. The mean systolic/diastolic blood pressure reductions were only 2.2/1.1 mmHg in 3691 patients recruited from China, much smaller than in patients recruited from other regions. However,the outcome results were not different between the Chinese and patients from other regions (P=0.48 for homogeneity across regions) [26].

Conclusions and Future Perspectives

There is some but insufficient outcome trial data from East Asians. Nonetheless, the currently available data suggested that antihypertensive treatment was highly efficacious in the prevention of cardiovascular complications especially stroke. The trials that compared intensive with less intensive antihypertensive therapy did not prove superiority of intensive blood pressure lowering to a level below 140 mmHg in elderly Japanese. These trials had a relatively small sample size and short duration of follow-up, and therefore probably had inadequate power for the detection of modest or moderate bene fit. There is a need for high quality outcome trials in East Asians, especially in the context of the recent Systolic Blood Pressure Intervention Trial(SPRINT) that clearly demonstrated outcome bene fit of intensive systolic blood pressure control to a level of 120 mmHg [27].

Conflict of Interest

Dr. Wang reports receiving lecture and consulting fees from MSD, Novartis, P fizer, Sankyo, Sano fi,and Servier. Dr. Li. declares no Conflict of interest.

Acronyms of Trials

CASE-J (Candesartan Antihypertensive Survival Evaluation in Japan Trial) [15]; COPE (The Combination Therapy of Hypertension to Prevent Cardiovascular Events) [16]; FEVER (Felodipine Event Reduction Study) [11]; HOPE-3 (Heart Outcomes Prevention Evaluation-3) [26]; HYVET(Hypertension in the Very Elderly Trial) [24, 25];IDNT (Irbesartan Diabetic Nephropathy Trial)[18]; JATOS (The Japanese Trial to Assess Optimal Systolic Blood Pressure in Elderly Hypertensive Patients) [20]; JMIC-B (Japan Multicenter Investigation for Cardiovascular Diseases-B) [14];NICS-EH (National Intervention Cooperative Study in Elderly Hypertensives) [13]; PATS (Poststroke Antihypertensive Treatment Study) [12];PROGRESS (Perindopril PrOtection Against Recurrent Stroke Study) [22, 23]; SPRINT (Systolic Blood Pressure Intervention Trial) [27]; STONE(Shanghai Trial of Nifedipine in the Elderly) [10];Syst-China (Systolic Hypertension in China trial)[9]; VALISH (The Valsartan in Elderly Isolated Systolic Hypertension) [21] and VALUE (Valsartan Antihypertensive Long-term Use Evaluation(VALUE) [17].

REFERENCES

1. Wu YK, Lu CQ, Gao RC, Yu JS,Liu GC. Nation-wide hypertension screening in China during 1979–1980. Chin Med J (Engl)1982;95:101–8.

2. Wu YK, Wu ZS, Yao CH.Epidemiologic studies of cardiovascular diseases in China. Chin Med J (Engl) 1983;96:201–5.

3. Wu X, Duan X, Gu D, Hao J,Tao S, Fan D. Prevalence of hypertension and its trends in Chinese populations. Int J Cardiol 1995;52:39–44.

4. Li LM, Rao KQ, Kong LZ, Yao CH,Xiang HD, Zhai FY, et al. Technical Working Group of China National Nutrition and Health Survey. A description on the Chinese national nutrition and health survey in 2002.Chin J Epidemiol 2005;26:478–84(Chinese).

5. Pan WH, Chang HY, Yeh WT,Hsiao SY, Hung YT. Prevalence,awareness, treatment and control of hypertension in Taiwan: results of Nutrition and Health Survey in Taiwan (NAHSIT) 1993–1996. J Hum Hypertens 2001;15:793–8.

6. Lee HS, Lee SS, Hwang IY,Park YJ, Yoon SH, Han K, et al.Prevalence, awareness, treatment and control of hypertension in adults with diagnosed diabetes:the Fourth Korea National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey(KNHANES IV). J Hum Hypertens 2013;27:381–7.

7. Otgontuya D, Oum S, Palam E,Rani M, Buckley BS. Individualbased primary prevention of cardiovascular disease in Cambodia and Mongolia: early identification and management of hypertension and diabetes mellitus. BMC Public Health 2012;12:254.

8. Miura K, Nagai M, Ohkubo T.Epidemiology of hypertension in Japan: where are we now? Circ J 2013;77:2226–31.

9. Liu L, Wang JG, Gong L, Liu G, Staessen JA, for the Systolic Hypertension in China (Syst-China)Collaborative Group. Comparison of active treatment and placebo for older Chinese patients with isolated systolic hypertension. J Hypertens 1998;16:1823–9.

10. Gong L, Zhang W, Zhu Y,Zhu J, Kong D, Pagé V, et al.Shanghai trial of nifedipine in the elderly (STONE). J Hypertens 1996;14:1237–45.

11. Liu L, Zhang Y, Liu G, Li W, Zhang X,Zanchetti A; FEVER Study Group.The Felodipine Event Reduction(FEVER) Study: a randomized long-term placebo-controlled trial in Chinese hypertensive patients. J Hypertens 2005;23:2157–72.

12. PATS Collaborative Group. Poststroke antihypertensive treatment study. A preliminary result. Chin Med J 1995;108:710–7.

13. National Intervention Cooperative Study in Elderly Hypertensives Study Group. Randomized double-blind comparison of a calcium antagonist and a diuretic in elderly hypertensives. Hypertension 1999;34:1129–33.

14. Yui Y, Sumiyoshi T, Kodama K, Hirayama A, Nonogi H,Kanmatsuse K, et al. Japan Multicenter Investigation for Cardiovascular Diseases-B Study Group. Comparison of nifedipine retard with angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitors in Japanese hypertensive patients with coronary artery disease: the Japan Multicenter Investigation for Cardiovascular Diseases-B(JMIC-B) randomized trial.Hypertens Res 2004;27:181–91.

15. Ogihara T, Nakao K, Fukui T,Fukiyama K, Ueshima K, Oba K,et al. Candesartan Antihypertensive Survival Evaluation in Japan Trial Group. Effects of candesartan compared with amlodipine in hypertensive patients with high cardiovascular risks: candesartan antihypertensive survival evaluation in Japan trial. Hypertension 2008;51:393–8.

16. Matsuzaki M, Ogihara T, Umemoto S, Rakugi H, Matsuoka H, Shimada K, et al. Combination Therapy of Hypertension to Prevent Cardiovascular Events Trial Group. Prevention of cardiovascular events with calcium channel blocker-based combination therapies in patients with hypertension:a randomized controlled trial. J Hypertens 2011;29:1649–59.

17. Julius S, Kjeldsen SE, Weber M, Brunner HR, Ekman S,Hansson L, et al. VALUE trial group. Outcomes in hypertensive patients at high cardiovascular risk treated with regimens based on valsartan or amlodipine: the VALUE randomised trial. Lancet 2004;363:2022–31.

18. Lewis EJ, Hunsicker LG, Clarke WR, Berl T, Pohl MA, Lewis JB,et al.; Collaborative Study Group.Renoprotective effect of the angiotensin-receptor antagonist irbesartan in patients with nephropathy due to type 2 diabetes. N Engl J Med 2001;345:851–60.

19. Wang JG, Li Y, Franklin S, Safar M. Prevention of stroke and myocardial infarction by amlodipine and angiotensin receptor blockers: a quantitative overview.Hypertension 2007;50:181–8.

20. JATOS Study Group. Principal results of the Japanese trial to assess optimal systolic blood pressure in elderly hypertensive patients (JATOS). Hypertens Res 2008;31:2115–27.

21. Ogihara T, Saruta T, Rakugi H, Matsuoka H, Shimamoto K, Shimada K, et al. Valsartan in Elderly Isolated Systolic Hypertension Study Group. Target blood pressure for treatment of isolated systolic hypertension in the elderly: valsartan in elderly isolated systolic hypertension study.Hypertension 2010;56:196–202.

22. PROGRESS Collaborative Group. Randomised trial of a perindopril-based blood pressure lowering regimen among 6105 individuals with prior stroke or transient ischaemic attack. Lancet 2001;358:1033–41.

23. Arima H, Anderson C, Omae T, Liu L, Tzourio C, Woodward M, et al.,PROGRESS Collaborative Group.Perindopril-based blood pressure lowering reduces major vascular events in Asian and Western participants with cerebrovascular disease:the PROGRESS trial. J Hypertens 2010;28:395–400.

24. Beckett NS, Peters R, Fletcher AE,Staessen JA, Liu L, Dumitrascu D, et al. HYVET Study Group.Treatment of hypertension in patients 80 years of age or older. N Engl J Med 2008;358:1887–98.

25. Liu L, Wang JG, Ma SP, Wang W, Lu FH, Zhang LQ, et al.Chinese subjects entered in the Hypertension in the Very Elderly Trial (HYVET). Chin Med J 2008;121:1509–12.

26. Lonn EM, Bosch J, López-Jaramillo P, Zhu J, Liu L, Pais P, et al. HOPE-3 Investigators.Blood-pressure lowering in intermediate-risk persons without cardiovascular disease. N Engl J Med 2016;374:2009–20.

27. SPRINT Research Group,Wright JT Jr, Williamson JD,Whelton PK, Snyder JK, Sink KM, et al. A randomized trial of intensive versus standard bloodpressure control. N Engl J Med 2015;373:2103–16.

Cardiovascular Innovations and Applications2016年3期

Cardiovascular Innovations and Applications2016年3期

- Cardiovascular Innovations and Applications的其它文章

- In flammasomes and Atherosclerosis

- The Gut Microbiota and Atherosclerosis:The State of the Art and Novel Perspectives

- Psychosocial Risk Factors and Cardiovascular Disease: Epidemiology, Screening, and Treatment Considerations

- Management of Hypertension: JNC 8 and Beyond

- ACC/AHA Guidelines for Cardiovascular Disease Prevention and Cholesterol Management:Implications of New Therapeutic Agentsa

- Smoking and Passive Smoking