How does auditors’work stress affect audit quality? Empirical evidence from the Chinese stock market

Huanmin Yan,Shengwen Xie

aSchool of Economics and Management,Nanchang University,China

bCenter for Accounting Studies,Jiangxi University of Finance and Economics,China

How does auditors’work stress affect audit quality? Empirical evidence from the Chinese stock market

Huanmin Yana,*,Shengwen Xieb

aSchool of Economics and Management,Nanchang University,China

bCenter for Accounting Studies,Jiangxi University of Finance and Economics,China

ARTICLEINFO

Article history:

Received 15 February 2015

Accepted 9 September 2016

Available online 18 October 2016

Auditors’work stress Audit tenure Individual characteristics Audit quality

With reference to the Job Demands–Control Model,we empirically examine the ef f ect of auditors’work stress on audit quality using a sample of Chinese A-share listed companies and their signature auditors from 2009 to 2013. The results show that(1)there is generally no pervasive deterioration in audit quality resulting from auditors’work stress;(2)there is a signif i cant negative association between work stress and audit quality in the initial audits of new clients;and(3)the perception of work stress depends on auditors’individual characteristics.Auditors from international audit firms and those in the role of partner respond more strongly to work stress than industry experts. Auditors tend to react more intensively when dealing with state-owned companies.We suggest that audit firms attach more importance to auditors’work stress and rationalize their allocation of audit resources to ensure high audit quality.

©2016 Sun Yat-sen University.Production and hosting by Elsevier B.V.This is an open access article under the CC BY-NC-ND license(http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/).

1.Introduction

Work stress has been referred to as an‘‘occupational f l u”in this era of the knowledge-driven economy(Lu, 2006).Under the mechanism of market competition,various professionals such as lawyers,doctors and executives all face some degree of work stress,as do auditors,who enjoy the reputation of the economic police.In the US,the Public Company Accounting Oversight Board has expressed concern that audit quality might be compromised due to auditors’workload or time pressure.1Auditing Standard No.7-Engagement Quality Review and Conforming Amendment to the Board’s Interim Quality Control Standards.Auditors in China suf f er from pervasive workstress resulting from time limits,human resources,liability risks,etc.Work stress peaks in the busy season, from January to February,when auditors’work schedules average more than 10 h per day.It is therefore logical to question(1)whether and how pervasive work stress affects auditors’decision-making and audit quality; and(2)whether auditors’response to work stress supports conf l ict theory or incentive theory,or both?

Despite its widespread existence in audit practice,academic studies concerning auditors’work stress are rare.The unavailability of large samples and the consequent absence of empirical evidence mean that a majority of studies are based on questionnaire surveys or experimental studies,and there is still no consensus among researchers(Jones et al.,2010;Liu and Zhang,2008).Fortunately,we have access to the mandatorily disclosed information on Chinese listed companies’signature auditors required by the China Securities Regulatory Commission(CSRC).Therefore,in this paper we empirically examine the effects of auditors’individual work stress on audit quality using large samples of listed companies and their corresponding signature auditors in the Chinese A-share market from 2009 to 2013,following the framework of the Job Demands–Control model proposed by Karasek(1979).We hope that our work will help to clarify the mechanism by which work stress affects audit behavior and the coping system regarding the stress response.

Specif i cally,the primary originalities and contributions of this paper are as follows:(1)Despite the fact that auditors’work stress is familiar to us in practice,academic studies concerning the issue are seldom addressed. This study helps to f i ll this gap by of f ering a logical argument and empirical evidence in the context of the Chinese stock market.(2)Our conclusion,which is more systematic than those in the literature based solely on the analysis of work demands(stressors),is drawn from a comprehensive study of the combined effects of work demands and work control,while taking into account the particular demands of auditing.(3)The paper enriches related studies on auditors’work stress from a psychological perspective by taking into consideration individual dif f erences in perception,thus leading to the finding that responses to work stress vary signif i cantly from person to person.

2.Literature review

Since the early twentieth century,with the development of industrialization and informatization,work stress has become an important issue in the f i elds of psychology,behavioral science and sociology.There has been widespread discussion regarding the def i nition of work stress,its influence mechanism and coping strategies,resulting in a series of outstanding academic achievements represented by Stimulation Theory, Response Theory(Selye,1976)and Interaction Theory(Karasek,1979),among others.The above studies indicate that individual responses to work stress can affect physical and mental health,work quality and even organizational performance through the stimulus and response system(Janssen,2001;Lu et al.,2010).However,the ef f ect of work stress on audit quality is seldom addressed in the f i eld of auditing studies.

First,among the diagnoses and experimental studies,Soobaroyen and Chengabroyan(2006)and Agoglia et al.(2010)argue that stress due to work or time budgeting tends to impair audit efficiency and quality.Liu (2008)claims that the time pressure of audit engagements could impede the proper implementation of audit procedures and damage audit quality,according to a survey of a nationwide audit f i rm.Stress due to time budgeting or deadlines also tends to aggravate auditors’perceived pressure(Margheim et al.,2011).Second, in terms of empirical studies,Lo´pez and Peters(2012)argue that workloads can damage audit quality at the level of the audit f i rm.A few scholars focusing on‘‘busyness”(which dif f ers from work stress)find it harmful to audit quality(e.g.,Sundgren and Svanstro¨m,2014),while others do not.For example,Goodwin and Wu (2016)suggest that the relationship between auditor busyness and audit quality depends on whether the former is in equilibrium,yet Choo(1986)finds an inverse U-shaped relation between the two.Choo’s work is supported by Huang and Bai(2014),who draw a similar conclusion from the results of a questionnaire survey involving several audit firms in China’s Nanjing,Suzhou and other regions.However,the universality of that conclusion is still under question given the limited representativeness of the study sample.

In the past 20 years,scholars have begun to consider auditors’work stress.However,the academic results are not fruitful,nor are the findings consistent.What is more,the literature discussing the effects of work stress on audit performance and quality is limited by a lack of reliability and generalizability,because most studies use experimental or survey designs.We are very fortunate that the accessibility of personal information on the auditors of Chinese listed companies,the market competition environment and the centralized auditing ofannual reports in peak season make it possible to carry out a systematic study.Given this,in this paper we provide an in-depth investigation of the topic from an individual perspective to address the shortage of academic research.This paper is expected to contribute to a solution to the practical issues concerning auditors’work stress,and at the same time providing scientif i c evidence for perfecting the regulatory policies on auditors’behavior.

3.Theoretical analysis and hypothesis development

Combining various interpretations of work stress,we def i ne it as a series of physiological,psychological and behavioral responses due to the continuing effects of one or more stressors on individuals in an organization(Xu,1999).In terms of auditing,auditors’work stress mainly results from the conf l ict between limited auditing resources and overwhelming audit workload within a limited time window(Lo´pez and Peters,2012).

According to the Job Demands–Control Model proposed by Karasek(1979),which is widely recognized in the f i elds of psychology and management science,work stress includes two key aspects:job demands and job control.The ef f ect of work stress depends on the interaction between work demands and work control.2In this paper,job demands and work demands and job control and work control are used synonymously.Work demands refer to difficulty and workload,including the amount of work,time and role conf l icts;work control reflects the individual’s response to work demands,including coping strategies and relief mechanisms.Previous studies find that work stress is positively related to the intensity of work demands,and negatively associated with work control(Landsbergis,1988;Fletcher and Jones,1993);moreover,work control is helpful for improving job satisfaction and job performance(Greenberger et al.,1989;Dwyer and Ganster,1991). In terms of auditing work,auditors’work demands(stressors)include multiple aspects ranging from time pressure and workload,cost control and performance evaluation to legal risk and responsibility.In view of work demands,an auditor’s work control ability(coping strategies)usually includes time planning,allocation of manpower and material resources,adjustment of the audit plan,etc.3In general,the work control strategies of an audit f i rm mainly include organizational support,incentive mechanism,etc.,but every auditor uses each of these strategies.Then,the joint ef f ect depends on the ef f ectiveness of the auditor’s work control over work demands,and the heterogeneity of an auditor’s work control ability will lead to different responses.Hence,given the quality control mechanism of an audit f i rm, how does an auditor’s work stress influence the audit behavior and audit quality?To clarify this mechanism, we analyze it from the perspective of time pressure,work load,cost and assessment,in the context of the competitive environment and institutional background of the Chinese audit market.

Time pressure is the main concern.Many studies show that time pressure,including time limitation pressure and time budget pressure,is the main factor affecting auditor behavior(Rhode,1978;Margheim et al., 2011).First,the CSRC stipulates that all listed companies should disclose their audited f i nancial reports before 30 April,which means that auditors face a clear time limitation pressure because they must f i nish all of the audit work within the prescribed time and issue a fair audit report.Usually,the auditing process is more complex when the auditee is larger,and auditors will bear a greater workload and take longer to complete the audit,so the time pressure is more obvious.For example,the auditor of PetroChina listed on the Main Board will experience greater time pressure than the auditor of Donghua Energy Ltd.,an SME-listed company in the energy industry.Second,according to preliminary data from the past f i ve years,auditors on average sign the f i nancial statements of more than three listed companies a year in the China stock market. The auditors in charge sign the audit reports of more than four companies on average,which means that they face a certain amount of stress from time budgeting.They have to allocate their work hours reasonably according to the features of each auditee.Usually,if an auditor takes a number of clients in a f i scal year, the working time allocated to each client will be less,and he will bear a heavier time budgeting pressure.Under the dual pressures of a prescribed time limit and time budgeting,auditors must take corresponding control measures,including allocating time to all clients and arranging the audit staf f,but whether these control measures can work e ff ectively depends on how well the time pressure is controlled.In general,as the time limitation and time budget pressures increase,the auditor’s boundary of control is likely to be exceeded,especially in the busy audit season when a number of engagements need to be carried out in parallel.Time pressure isgreater,and it becomes difficult to ensure that each client has enough disposable time to implement full audit procedures appropriately,so auditors have to compress time or even cut short audit procedures(Willett and Page,1996;Soobaroyen and Chengabroyan,2006),which directly affects the reliability and adequacy of the audit evidence obtained,and thereby affects the efficiency of the audit judgment(Pierce and Sweeney,2004).

Second,workload and job burnout are discussed.In China,auditing is recognized as a special service performed under high stress,but with low job satisfaction.Generally,in the busy annual audit season, the more engagements an auditor undertakes,the more difficult or complicated the auditing projects,so the greater the workload intensity.In view of the high intensity of the workload,the auditor and his team often implement control measures such as lengthening their working hours,sometimes for several months, which undoubtedly influences the efficiency and ef f ectiveness of auditing work.The possible negative consequences include the unreasonable compression of audit time,and following audit procedures in a parrot-like fashion(Agoglia et al.,2010).More importantly,auditors who experience intense time pressure and bear a high-intensity workload,beyond their capacity and over a long period,will suf f er from job burnout.4Job burnout is a comprehensive set of symptoms including individual emotional exhaustion,the disintegration of personality and low personal accomplishment.Moreover,the greater the workload pressure,the stronger the sense of job burnout will be.Further,auditors’job burnout can lead to emotional exhaustion,extreme tiredness or even depersonalization (Sweeney and Summers,2002).The potential consequences of such manifestations include reduced professional skepticism and audit efficiency,such as accepting questionable evidence;less recalculation or reexecution of programs that are time consuming and labor intensive;and a reduction in the necessary analyses,which make it difficult to identify inconsistent f l uctuations between the auditee and its industry information or anomalies between the actual and expected data.Hence,there is less likelihood of detecting accounting dif f erences or misstatements and an increased probability of audit failure,f i nally resulting in reduced audit quality(Margheim et al.,2011).

Third,audit cost and performance appraisal are considered.Although people regard auditors as the‘‘economic police,”auditors are responsible for their own prof i ts and losses,and are economic actors with limited rationality.They must,therefore,comply with the‘‘cost-benef i t principle,”with limitations on the expenditures for each auditee,including manpower and physical resources.It is necessary to match audit quality with audit fees.In general,under the premise of the given audit resources of an audit f i rm,the more complex and difficult the audit projects,the more clients there are,and the greater the resource constraints and cost control pressure.In the busy audit season,the cost control pressure on auditors conf l icts with the quality control requirements of the audit f i rm.This is especially true when there is intense audit market competition,and performance appraisal systems tend to be based on the time budget.In short,this kind of conf l ict increases the potential for unethical behavior,such as spending less time on audits or even violating auditing standards, thus increasing the probability of audit failure(Liu,2008).

Fourth,auditors are subject to legal risks and responsibilities.Given the changing economic environment, industry globalization,increasingly complicated business transactions and f i nancial accounting,auditors are facing growing difficulties in their work.However,public investors tend to place increasing expectations on auditors due to contract objectives,decision making and risk aversion(Schipper and Vincent,2003).In addition,with the gradual improvements in audit laws and regulations,the legal risks and responsibilities of audit fi rms and auditors for failing to carry out proper auditing are become increasingly explicit.In contrast, improvements in audit knowledge and technological innovations are relatively slow,resulting in unbalanced development and an increasing gap between investors’expectations and auditors’ability.This gap further intensi fi es auditors’stress and escalates the e ff ects of stress on auditing behavior and quality.

In summary,individual work stress is created by the combined e ff ects of time pressure,workload,cost control,performance appraisal,legal risks and responsibilities.This stress,along with the resulting job burnout, in fl uences auditors’psychological activities and behavioral decisions,which in turn a ff ect audit efficiency and quality.Usually,the greater the stress,the greater the observed e ff ects;however,consistent with Incentive Theory,it is possible that the e ff ects of stress on audit quality might be limited or even bene fi cial when there are e ff ective work controls on work demands(McClenahan et al.,2007).Nevertheless,the relationship betweenwork stress and audit quality remains an empirical question that is yet to be tested.Thus,we propose the following hypothesis:

H1.Auditors’work stress affects audit quality.

Next,we consider whether the relationship between auditors’work stress and audit quality is subject to other factors due to the distinctiveness of auditing work.Audit tenure may be one such factor.Specif i cally, to evaluate the audit risk during the initial audit of a new client,the auditor must gain a comprehensive understanding of the client’s operating characteristics,accounting policies,industry development and other information.In this case,the auditor needs to invest more initial audit costs in the new client,including working hours,human and material resources and so on.The more clients an auditor is responsible for, the greater the total workload and the fewer working hours and audit resources he will able to spend on each client,especially new clients.This is how the direct conf l ict between work demand and work control is created. Moreover,the more intense the conf l ict,the greater the work stress and its negative effects are likely to be,and the greater the negative consequences on the audit performance,the provision of sufficient evidence and the efficiency of the audit judgment.Correspondingly,in non-initial audits for continuing clients,5In this paper,an‘‘old client”refers to a company that has been audited by a signature auditor at least once;that is,the audit tenure is at least two years.given a certain total workload and stress,the ef f ectiveness of work controls on work demands tends to improve with subsequent audits,and the accumulation of experience and knowledge acquired through the familiarity with and mastery of specif i c client and industry information.The improvement in ef f ectiveness then mitigates the negative effects of work stress on audit quality.This analysis leads to the second hypothesis:

H2.The influence of auditors’work stress on audit quality is mainly observed in the initial audit engagement of a new client.

4.Research design

4.1.Sample and data

Our sample comprises A-share companies listed on the Shanghai and Shenzhen stock markets from 2009 to 2013.Financial data for these companies are derived from the CSMAR database,and each auditor’s personal information is manually collated and corrected according to company annual reports and information system of the CICPA.Consistent with former studies,we remove(1)companies in the f i nance industry;(2)companies with missing f i nancial data for the previous year,with initial public of f erings or with less than 15 industry-year observations in the calculation of discretionary accruals;and(3)companies with missing data on the signature auditor.Additionally,we winsorize the continuous variables in the intervals 0–1%and 99–100%.The f i nal sample includes 9639 f i rm-year observations.

4.2.Variables and model

4.2.1.Variable def i nitions

(1)Auditors’work stress(WS).Work stress is measured by the number of listed companies audited by an auditor,taking into consideration both the number of companies and the business complexity of each company.Therefore,we estimate work stress by the following equation:

where for listed company j audited by auditor i,TAijrefers to the natural logarithm of total assets;n is the total number of listed companies audited by auditor i in the f i scal year;and m is the number of signature auditors of specif i c company j.In the majority of cases,there are two auditors in charge of audit-ing a company’s annual report(m=2),although in a few cases there are three(m=3,accounting for about 1.75%).WS reflects the average work stress borne by the two or three signature auditors of a specif i c company.

(2)Audit quality.Audit quality is measured by the absolute value of discretionary accruals(DA)using the Modif i ed Jones Model.In addition,we use audit failure as a substitute variable in the robustness tests.

(3)Initial audit.The initial audit is def i ned as the first audit of a company and the signing of the corresponding annual reports:FST equals 1 for new clients,and 0 otherwise(see Table 1).

4.3.Model design

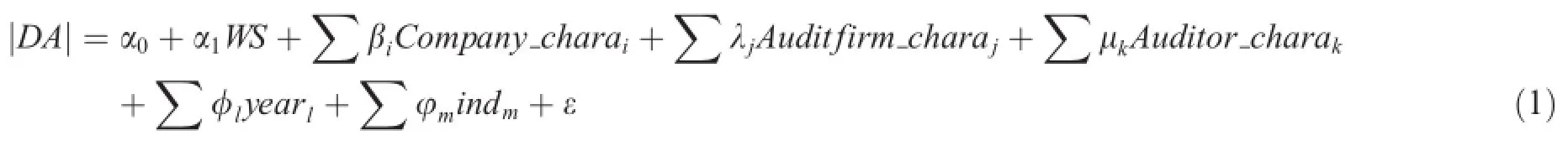

(1)Test of Hypothesis 1 We establish model 1 to test the influence of auditors’work stress on audit quality.

|DA|refers to the absolute value of discretionary accruals,as a proxy of audit quality.WS refers to auditors’work stress,which is expected to be positive.We take three determinants of audit quality into consideration:company characteristics(Company_chara),audit f i rm characteristics(Auditf i rm_chara)and auditor characteristics(Auditor_chara),drawing on the experience of Xue et al.(2012),Gul et al. (2013),among others.

Table 1Variable def i nitions.

Table 2Descriptive statistics.

(2)Test of Hypothesis 2

We establish model 2 to test the influence of auditors’work stress on audit quality with different audit tenures.

WS*FST refers to the interaction term between WS and FST,which is expected to be positive.To test hypothesis H2,the analysis is divided into two steps.First,we conduct a regression test on model 1 grouped by initial audit(FST equals 1 or 0),and second,we include the interaction term(WS*FST) and conduct another regression test on model 2.

5.Empirical results and analysis

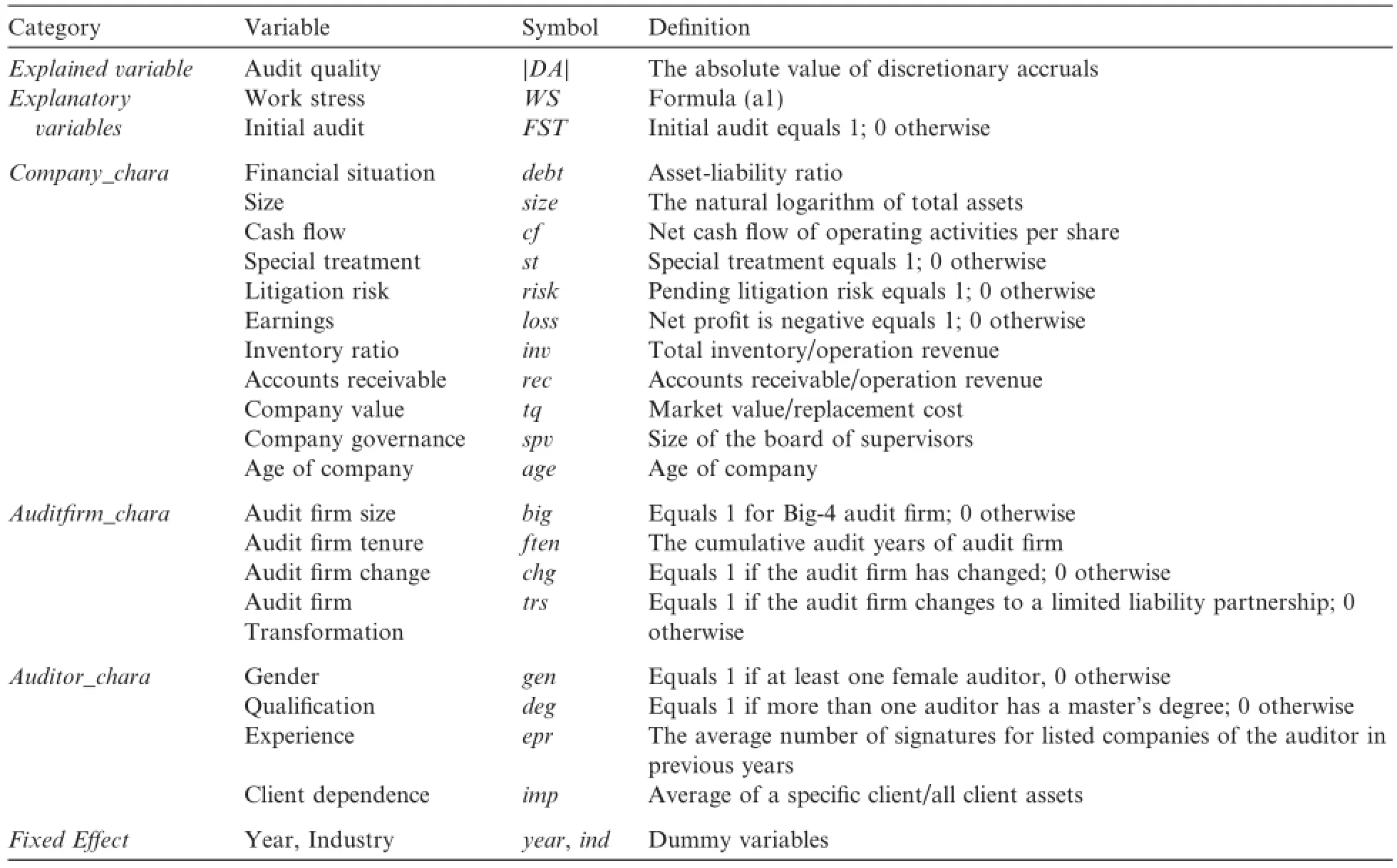

5.1.Descriptive statistics and correlation analysis

Tables 2 and 3 report the descriptive statistics and correlation analyses.6We also test whether there is a u-shaped relationship between work stress and audit quality.The results show that the Pearson coefficient of|DA|and WS squared is not signif i cant,and the univariate and multivariate analyses show that the regression coefficient of WS squared is not signif i cant.Moreover,the robustness test using alternative measurements of work stress and audit quality does not support a u-shaped relationship.Table 2 shows that there is substantial variation in WS,making it suitable for analyzing work stress reactions at the individual level. In terms of the composition of audit clients,new clients account for about 14.5%.Table 3 shows that the correlation between WS and|DA|is insignif i cant in the full sample.After distinguishing by audit tenure, the correlation between WS and|DA|is signif i cantly positive at the 5%level in the initial audit,while it is insignif i cant in the non-initial audit.Moreover,the correlation between WS*FST and|DA|is signif i cantlypositive.This indicates that the ef f ect of auditors’work stress on audit quality is more obvious in the initial audits of new clients,which is yet to be further tested.

5.2.Multivariate analysis

5.2.1.Preliminary test of the full sample

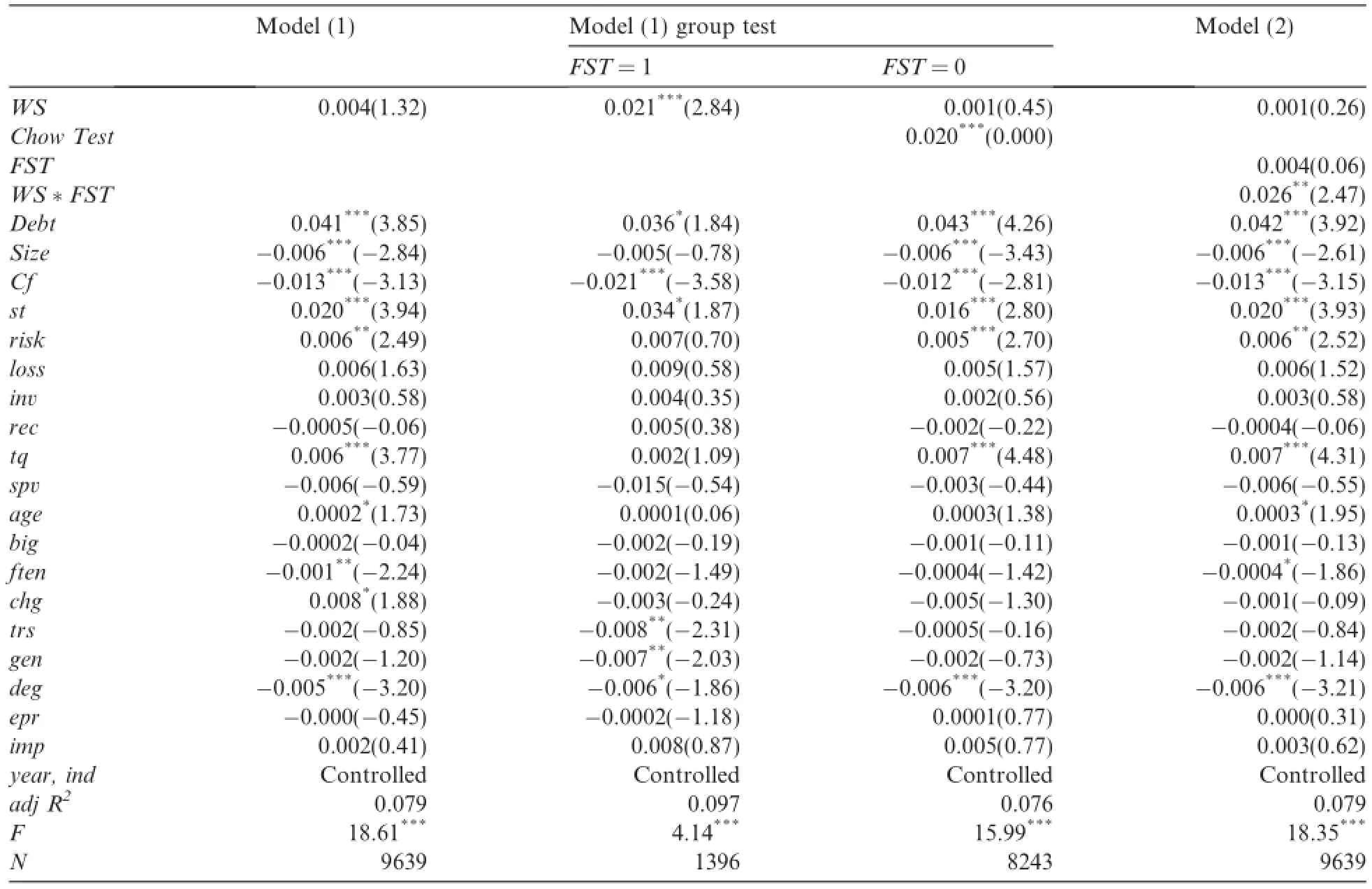

Table 4 reports the regression results of the full sample.The results of model 1 show that when audit quality is measured by|DA|,the coefficient of WS is positive but not signif i cant,suggesting that work stress does not impair audit quality overall in the Chinese audit market.Therefore,the finding that auditors’work stress is controlled fails to support H1.However,this does not mean that auditors’work stress has no ef f ect,as we still need to consider the particular details of audit work.

5.2.2.Considering audit tenure

Considering audit tenure,first,the result of model(1)shows that the coefficient of WS is signif i cantly positive at the 1%level in the initial audits of new customers(FST=1),but decreases and is non-signif i cant in non-initial audits(FST=0).Moreover,the results of the Chow test show a signif i cant dif f erence between these two groups.Second,when the interaction term(WS*FST)is included in model(2),the coefficient of WS*FST is signif i cantly positive at the 5%level.These results show that signature auditors have different work stress reactions with different audit tenures.The ef f ect of work stress on audit quality is mainly indicated in the initial audit,ref l ecting a negative reaction,which supports H2.In other words,in the initial audits of new clients,the conf l ict between work demands and work control exerts a negative ef f ect on audit efficiency and audit quality due to unclear business features,accounting methods and industry information.This evidence supports the Conf l ict Theory.However,in the non-initial audit stage,the effects of learning by doing, which occur with the accumulation of audit experience and the acquisition of relevant knowledge,can enhance the signature auditor’s work control capability and ease the negative ef f ect of work stress.

Among the control variables,some coefficients of size and cf are signif i cantly negative,while other coefficients of debt,st and risk are signif i cantly positive,indicating that earnings quality is better in larger companies that have better cash f l ow.This result is consistent with previous studies(Xue et al.,2012).In addition,the signif i cantly negative coefficient of deg suggests that highly educated auditors help to ensure a high quality audit.

6.Further analysis

6.1.Perception of work stress varies from person to person

Audit work has a distinct people-oriented characteristic,which means that auditors’perceptions of work stress and their reactions are likely to vary from person to person.Individuals dif f er in their ability to cope with the same level of work stress.different auditors adopt different coping strategies with varying degrees of ef f ectiveness,which eventually leads to work stress having different effects on audit quality.Previous studies also indicate that individual heterogeneity is an important factor affecting audit quality.There are two main factors that influence auditors’perceptions of stress:individual heterogeneities,such as the auditor’s role,industry expertise,gender and age;and audit f i rm heterogeneities,such as the efficiency of quality control mechanisms,support mechanisms and mechanisms for sharing legal responsibility.

Table 4Multivariate regression.

6.1.1.The role of signature auditors

In China,the annual f i nancial reports of listed companies should be audited and signed by at least two auditors to clarify the legal responsibility,which means that the different roles of signature auditors determine different legal responsibilities.Specif i cally,partner auditors have responsibility for the residual control and income of the audit f i rm and thus bear more legal responsibilities than non-partners.In particular,after a partnership is transformed into a limited liability partnership,the legal responsibilities of the partners increase signif i cantly.Therefore,it is possible that the different legal responsibilities of partners and non-partners may lead to dif f erences in their reactions to stress.

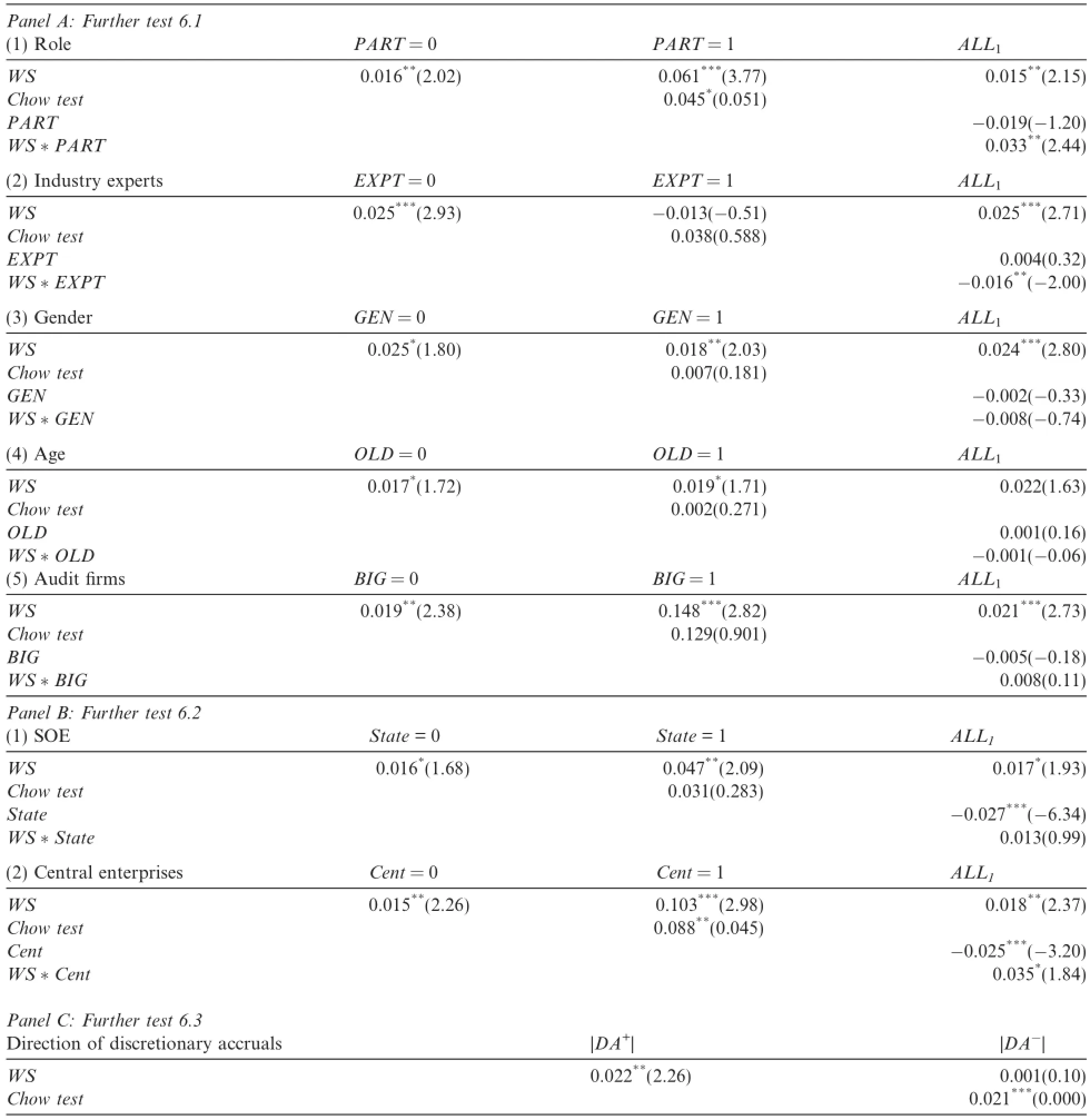

For this purpose,we partition the full sample into two groups:partners(PART equals 1)and non-partners (PART equals 0).7If all signature auditors are partners,we def i ne it as a partners’group,and otherwise as a non-partners’group.We test the sample of non-initial audits(old clients),but do not draw any evidential conclusions.As shown in Panel A of Table 5,when PART equals 0,the regression coefficient of work stress(WS)is 0.016 and signif i cant at the 5%level in the initial audit engagement of a new client.When PARTequals 1,the regression coefficient of WS increases to 0.061 and signif i cant at the 1%level,and the Chow test shows that there is a signif i cant dif f erence between the two groups.In addition,the coefficient of the WS*PART interaction is signif i cantly positive at the 5%level.These results comprehensively indicate that partner auditors have a stronger response to stress than non-partners.The reasonable explanation for this phenomenon is that partners of audit firms bear relatively more legal responsibilities and are more conscious

of their brand reputation.Although we do not deny that this can urge partners to ensure the quality of audit,it also leads to greater work stress in response to the same workload,which increases work stress indirectly.

Table 5Further tests.

6.1.2.Industry expertise

Industry expertise is behind the saying,‘‘Able men are always busy”:the most able auditors can be deemed industry experts.Compared with non-experts,does the advantage of experience in the client’s industry ease the stress reaction in the initial audit of a new client?

For this purpose,we partition the full sample into two groups:industry experts(EXPT equals 1)and nonexperts(EXPT equals 0).8If at least one of the signature auditors has audited more than f i ve companies belonging to the same industry within in the previous year,we def i ne it as an expert group,and otherwise as a non-expert group.In the sample of initial audits(new clients),the accumulated number of companies audited within the previous year is 1.8 on average,which is lower than the mean value of 4.8 in the full sample. Similar to the study by Xue(2012),we use the def i nition standard of the top 20%and top 20 in the industrial market,and we f i nally obtain consistent conclusions.Panel A of Table 5 shows that the coefficient of WS is 0.025 and signif i cant at the 1%level in the group of non-experts(EXPT equals 0),while WS is insignif i cant in the group of industry experts(EXPT equals 1).The Chow test shows that there is no signif i cant dif f erence between these two groups, but the coefficient of WS*EXPT is signif i cantly negative.This shows that the ef f ect of industry experts cannot completely eliminate,but does partially alleviate,the negative effects of auditors’work stress on audit quality.

6.1.3.The gender of signature auditors

In daily life,males and females have different physiological and psychological responses to stress,and thus theirperceptionsandreactionstoworkstressaredifferent.Therefore,weexaminewhethertheeffectsofauditors’work stress dif f er between males and females.We def i ne a group that includes at least one female auditor as a female group(GEN equals 1),and otherwise as non-female(GEN equals 0).9In addition,if all signature auditors are female we def i ne the group as female,and otherwise as non-female;we find no signif i cant dif f erence between these two groups.Panel A of Table 5 shows that the coefficients of WS in the non-female group are larger than in the other,but the dif f erence is not signif i cant. This indicates that there is no signif i cant correlation between an auditor’s gender and the ef f ect of work stress.

6.1.4.The age of signature auditors

People of different ages may have different perceptions of and reactions to work stress.In terms of audit work,younger auditors are usually able to withstand greater work intensity such as increased working hours. However,older auditors have richer experience that may help to ease the perception of work stress.Therefore, we examine whether work stress is influenced by auditors’age.We partition the full sample into two groups: an old(OLD equals 1)and a non-old group(OLD equals 0).10If the average age of the signature auditor is greater than the mean value of 44.19,then the group is classif i ed as old,and otherwise as non-old.The results in Table 5 show that there is no signif i cant dif f erence between the two groups,which means that the ef f ect of work stress on audit quality is not influenced by the auditor’s age.

6.1.5.Audit f i rm characteristics

The audit service provided by an auditor clearly relies on the audit f i rm,so the audit f i rm’s mechanisms for restraining auditors’professional behavior are likely to affect perceptions of and reactions to work stress. Specif i cally,the audit quality control mechanism and the work support mechanism for auditors,such as the allocation of audit resources and peer review mechanism,di ff er depending on the scale and type of audit fi rm.These factors together constitute the behavior constraint mechanism,which a ff ects auditors’psychological perception.In short,the heterogeneous characteristics of di ff erent audit fi rms can also a ff ect the perception and reaction of work stress.Fortunately,the Chinese audit market provides a natural condition,namely the co-existence of local and Big 4 audit fi rms.As the quality control mechanism,sta ffsupport and restraint mechanisms of these two kinds of fi rms are di ff erent,is there any di ff erence in work stress response?

We partition the full sample into two groups:local fi rms(BIG equals 0)and Big 4 fi rms(BIG equals 1). Table 5 shows that compared with local audit fi rms,the auditors of Big 4 fi rms have a more obvious stressresponse,but the dif f erence between the two groups is not signif i cant.This lack of dif f erence may be due to the joint ef f ect of two forces:on the one hand,compared to local audit firms,Big 4 firms usually provide better work support and incentive mechanisms for auditors,which can ease work stress;on the other hand,perhaps more importantly,the need for Big 4 firms to protect their strong brand reputation and reduce risk imposes more rigid service requirements and stricter restrictions,which may enhance the auditor’s perception of and reaction to work stress.

6.2.Property nature of audit clients

Listed companies in the Chinese security market can be divided into state-owned companies and non-stateowned companies according to their property.In terms of state-owned companies,central holding companies and local government holding companies coexist,which are characteristics of the Chinese security market.In particular,the central holding companies have to be audited by both a public audit f i rm and the Chinese National Audit Office.Therefore,is there any dif f erence in the perception of and response to work stress for the two types of companies?

Based on this characteristic of the Chinese security market,we conduct further analysis.In Panel B of Table 5,we divide the full sample into state-owned companies(State equals 1)and non-state-owned companies(State equals 0).The results show that the reaction to work stress is more obvious in the sub-sample of state-owned companies,but this dif f erence is not signif i cant.We then divide the full sample into central holding companies(Cent equals 1)and local government holding companies(Cent equals 0),and the results show that the reaction to work stress is more obvious in the sub-sample of central holding companies,and the Chow test shows that the dif f erence is signif i cant.The coefficient of WS*Cent is also signif i cantly positive.These results show that government audits increase auditors’work stress and negative reactions,but unfortunately government audits do not enhance the quality of independent audits.

6.3.Direction of discretionary accruals

Wedividethefullsampleintotwosub-samplesbydistinguishingbetweenpositivediscretionaryaccruals(|DA +|)and negative discretionary accruals(|DA-|).The regression results listed in Panel C of Table 5 show that the coefficient of WS is signif i cantly positive in the positive(|DA+|)but not in the negative discretionary accruals(| DA-|)sub-group.This dif f erence between the two sub-samples is signif i cant,indicating that the negative reaction to work stress is mainly embodied in tolerating the positive discretionary accruals of initial audit clients.

7.Robustness tests

To strengthen the reliability of the results,we perform the following robustness tests.

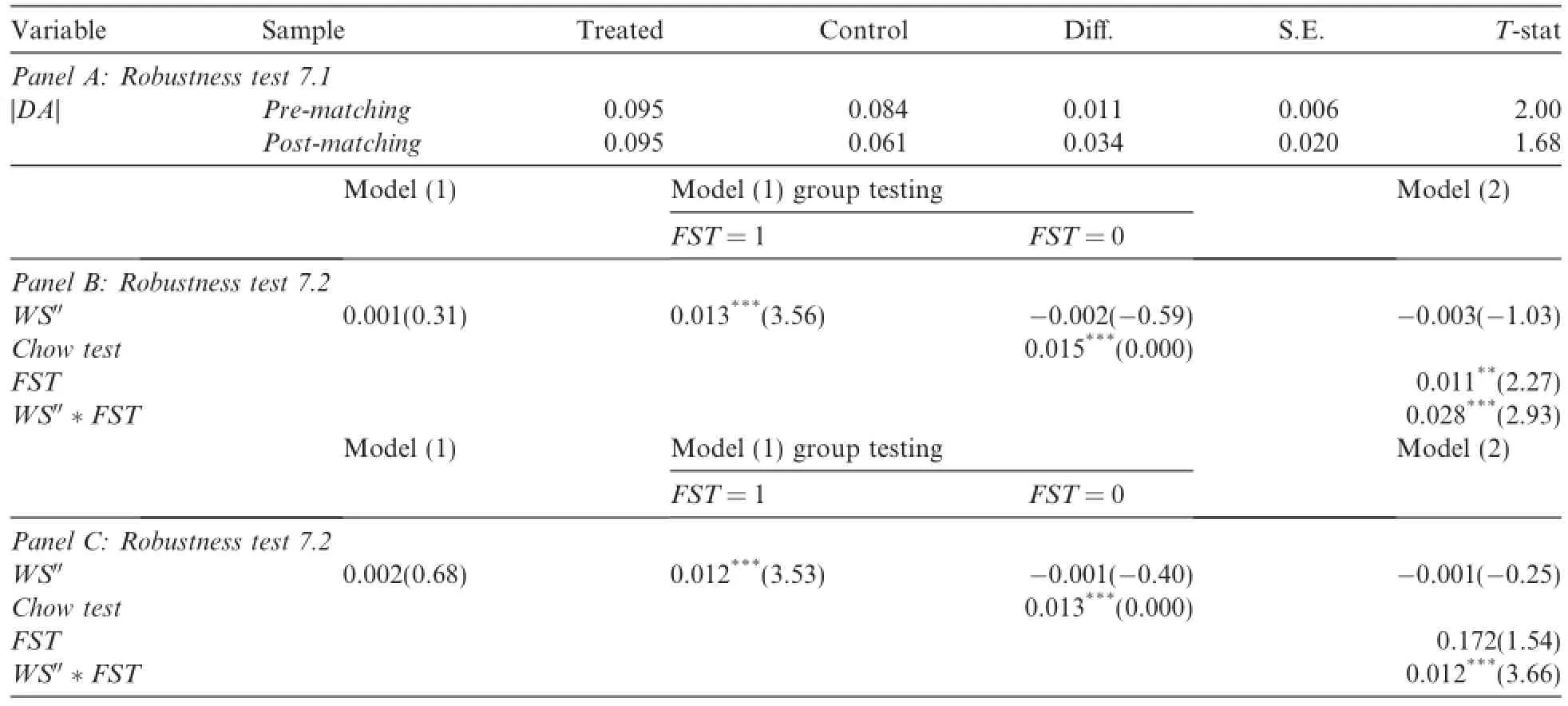

7.1.Endogeneity test

In exploring the relationship between auditors’work stress and audit quality,there may be a problem with client-auditor self-selection;that is,auditors with a heavy workload and high stress may exercise less discretion in selecting clients.They may be more likely to accept clients with poor quality accounting information,which leads to lower audit quality.To alleviate this problem,we adopt the propensity score matching method.First, we calculate the median of auditors’work stress by sub industry and sub year,and judge the intensity of work stress accordingly.We classify those with stress levels higher than the median as the treated group,and the rest as the control group.Then,we use the nearest neighbor matching method to perform tests.The results listed in Table 6 show that the T value is 2.00 before and 1.68 after the nearest neighbor matching,suggesting that there is a signif i cant positive correlation between WS and|DA|in the initial audits of new clients.11Other empirical results,which are not shown in Table 6 due to limited space,indicate that the T values are 1.68 and 1.79 using the radius matching method and kernel matching method,respectively,which are consistent with the above.In addition,we use the above methods to test the full sample,and obtain consistent conclusions.

Table 6Robustness tests.

7.2.Alternative measurement of auditors’work stress

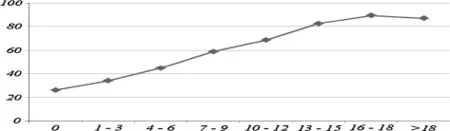

There is an occupational characteristic of audit work:the longer an auditor works,the more his qualif i cations and abilities increase,as well as the number of clients.In Fig.1,the horizontal axis represents the accumulated working years of auditors before the observation year,and the vertical axis represents auditors’business workload(the mean value of the sum of the natural logarithm of the audit client’s assets).To rule out the possible ef f ect of auditors’qualif i cations or abilities on the measurement of auditors’work stress, we adopt the following specif i c methods.First,according to the number of working years(Years)accumulated before the observation year,we divide the auditors into eight grades(N)with 3-year intervals12The maximum and minimum numbers of Years are 0 and 20;Years=0 is def i ned as the first year(N equals 1);Years=(1–3)is def i ned as the second year(N equals 2);Years>18 is def i ned as the eighth year(N equals 8).;second,we calculate the annual average workload of various grades of auditors(V_N);and third,we def i ne WS''as the measurement of work stress in the regression analysis,where WS''is equal to WS minus V_N.

The results in Table 6 show that the coefficients of WS''and WS''*FST are signif i cantly positive,which means that auditors’work stress has a signif i cantly negative ef f ect on audit quality only in the initial audits of new clients.Furthermore,considering auditors’individual characteristics,empirical results that are not shown due to the limited space indicate that the stress reaction of partner auditors is more pronounced, but industry experts can partially alleviate the reaction.However,the stress reaction has no signif i cant association with the gender or age of signature auditors.

7.3.Alternative measurement of audit quality

Figure 1.Diagram of auditors’working years and workload.

Following previous studies(Xie and Yan,2014),audit failure(AF)is adopted as an alternative measurement of audit quality.13If the signature auditors issue a company with a clean opinion,but a fi nancial restatement occurs after the disclosure of the annual fi nancial report,AF equals 1,and 0 otherwise.The sample of fi rms with fi nancial restatements is sorted manually from fi nancial statement footnotes and restatements.Table 6 shows that the coefficient of WS''is signif i cantly positive only in the sample of initial audits of new clients,and the coefficient of WS''*FST is signif i cantly positive.In addition,according to the signature auditors’individual characteristics including their role,industry expertise,sex and age,the results(which are not shown due to limited space)are in accordance with the above.

8.Conclusions

Work stress can affect work quality and organizational performance.The auditing industry is a peopleoriented industry and the work stress of auditors cannot be neglected.However,the literature on auditors’work stress reactions and coping mechanisms is insufficient,as it lacks studies with large samples and empirical evidence.This paper takes advantage of the favorable condition in the Chinese stock market,which requires mandatory disclosure of the signature auditors’personal information.With reference to the Job Demands–Control Model,we empirically examine the effects of auditors’individual work stress on audit quality using a sample of listed companies on the Chinese A-share market and their corresponding signature auditors from 2009 to 2013.The main findings are as follows.(1)In general,there is no pervasive deterioration in audit quality resulting from auditors’work stress that is under control.(2)There is a signif i cant negative association between work stress and audit quality in the initial audits of new clients after setting apart different stages of audit tenure,due to the lack of comprehensive understanding of client and industry information.However, with the learning by doing ef f ect brought about by ongoing auditing,the negative response reaction tends to be reduced.(3)Perceptions of work stress and related responses vary from person to person according to signature auditors’individual characteristics.The results suggest that auditors from international audit firms and those in the role of partner show a more distinct response to work stress while auditors with industry expertise demonstrate a weaker reaction.However,there is no evidence that gender or age affects auditors’stress response.Auditors also tend to be more sensitive and react more intensively when dealing with state owned, especially central government owned,enterprises.

In summary,based on a comprehensive analysis and discussion of the relationship between work pressure and audit quality at the individual level,this paper clarif i es the mechanism by which work stress affects audit behavior and the coping system in response to stress.The findings not only make up for the shortage of empirical studies,but also of f er a perspective on and evidence from the Chinese stock market.More importantly,our findings provide practical guidance on the standardization of auditors’behavior and the quality management of audit firms.Specif i cally,to ensure service quality,we recommend that experienced auditors be assigned to new clients because negative responses toward stress are most apparent in initial audits.Second,we favor the exchange of internal experience within audit firms,the ongoing accumulation of client and industry information and the cultivation of industry expertise.Third,we advise auditing regulators and supervising departments to consider the establishment of an upper limit on the number of clients during busy periods,with full consideration of multidimensional factors including the audit f i rm’s features and individual auditors’capabilities.These measures should help to resolve the negative effects of overwhelming work stress on audit quality.We admit that these suggestions may contain certain biases and execution difficulties in audit practice,which concern problems that need prompt resolution,further analysis and practical examination.

Acknowledgments

This paper received f i nancial support from the National Natural Science Foundation of China(Nos. 71662021 and 71462014).We owe many thanks to Prof.Xingqiang Du(our discussant at the CJAR special issue conference,April 2015),Oliver Zhen Li,Donghua Chen and the anonymous reviewers for their helpful comments and suggestions.All errors remain our own.

Agoglia,C.P.,Brazel,J.F.,Hatf i eld,R.C.,Jackson,S.B.,2010.How do audit workpaper reviewers cope with the conf l icting pressures of detecting misstatements and balancing client workloads?Auditing:J.Practice Theory 29(2),27–43.

Choo,F.,1986.Job stress,job performance,and auditor personality characteristics.Auditing:J.Practice Theory 5(2),17–34.

Dwyer,D.J.,Ganster,D.W.,1991.The effects of job demands and control on employee attendance and satisfaction.J.Org.Behav.12(7), 595–608.

Fletcher,B.C.,Jones,F.,1993.A refutation of Karasek’s demand-discretion model of occupational stress with a range of dependent measures.J.Org.Behav.14(4),319–330.

Goodwin,J.,Wu,D.,2016.What is the relationship between audit partner busyness and audit quality?Contemp.Account.Res.33(1), 341–377.

Greenberger,D.B.,Strasser,S.,Cummings,L.L.,Dunham,R.B.,1989.The impact of personal control on performance and satisfaction. Org.Behav.Hum.Decis.Process.43(1),29–51.

Gul,F.A.,Wu,D.,Yang,Z.,2013.Do individual auditors affect audit quality?Evidence from archival data.Account.Rev.88(6),1993–2023.

Huang,H.,Bai,P.,2014.CPA’s job stress,perceived organizational support and job performance.Auditing Res.2,89–94(in Chinese).

Janssen,O.,2001.Fairness perceptions as a moderator in the curvilinear relationships between job demands,and job performance and job satisfaction.Acad.Manage.J.44(5),1039–1050.

Jones III,A.,Norman,C.S.,Wier,B.,2010.Healthy lifestyle as a coping mechanism for role stress in public accounting.Behav.Res. Account.22(1),21–41.

Karasek,R.A.,1979.Job demands,job decision latitude,and mental strain:implications for job redesign.Adm.Sci.Q.24(2),285–307.

Landsbergis,P.L.,1988.Occupational stress among health care workers:a test of the job demand-control model.J.Org.Behav.9(3),217–239.

Liu,C.,2008.CPA behavior under time pressure:evidence from a large f i rm.Auditing Res.2,79–85(in Chinese).

Liu,C.,Zhang,J.,2008.Time pressure,accountability and audit judgment performance:an experimental study.China Account.Rev.4, 405–424(in Chinese).

Lo´pez,D.M.,Peters,G.F.,2012.The ef f ect of workload compression on audit quality.Auditing:J.Practice Theory 31(4),139–165.

Lu,C.,2006.Flu of 21st century:killer of happiness.People’s Tribune 6,16–18(in Chinese).

Lu,L.,Kao,S.F.,Siu,O.L.,Lu,C.Q.,2010.Work stressors,Chinese coping strategies,and job performance in Greater China.Int.J. Psychol.45(4),294–302.

Margheim,L.,Kelley,T.,Pattison,D.,2011.An empirical analysis of the effects of auditor time budget pressure and time deadline pressure.J.Appl.Bus.Res.21(1),23–27.

Mcclenahan,C.A.,Giles,M.L.,Mallett,J.,2007.The importance of context specif i city in work stress research:a test of the demand–control–support model in academics.Work Stress 21(1),85–95.

Pierce,B.,Sweeney,B.,2004.Cost–quality conf l ict in audit firms:an empirical investigation.Eur.Account.Rev.13(3),412–441.

Rhode,J.G.,1978.Survey on the influence of selected aspects of the auditor’s work environment on professional performance of certif i ed public accountants.Summarized in The Commission on Auditors’Responsibilities:Report of Tentative Conclusions.New York,NY: AICPA.

Schipper,K.,Vincent,L.,2003.Earnings quality.Account.Horizons 17(Suppl.),97–110.

Selye,H.,1976.The Stress of Life,vol.1.McGraw-Hill Book Company,New York,pp.30–42.

Soobaroyen,T.,Chengabroyan,C.,2006.Auditors’perceptions of time budget pressure,premature sign of f s and under-reporting of chargeable time:evidence from a developing country.Int.J.Auditing 10(3),201–218.

Sundgren,S.,Svanstro¨m,T.,2014.Auditor-in-charge characteristics and going-concern reporting.Contemp.Account.Res.31(2),531–550.

Sweeney,J.T.,Summers,S.L.,2002.The ef f ect of the busy season workload on public accountants’job burnout.Behav.Res.Account.14 (1),223–245.

Willett,C.,Page,M.,1996.A survey of time budget pressure and irregular auditing practices among newly qualif i ed UK chartered accountants.British Account.Rev.28(2),101–120.

Xie,S.,Yan,H.,2014.Comparative study on the ef f ect of CPA f i rm rotation and CPA rotation.Auditing Res.4,81–88(in Chinese).

Xu,C.,1999.Work stress system:mechanism,handling and management.J.Zhejiang Normal Univ.:Social Sci.5,69–73(in Chinese).

Xue,S.,Ye,F.,Fu,C.,2012.Partners’industry expertise,tenure and audit quality:evidence from China.China Account.Finance Rev.3, 109–133(in Chinese).

*Corresponding author.

E-mail addresses:yhmjxufe@163.com(H.Yan),xieshw@126.com(S.Xie).

http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.cjar.2016.09.001

1755-3091/©2016 Sun Yat-sen University.Production and hosting by Elsevier B.V.

This is an open access article under the CC BY-NC-ND license(http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/).