Management earnings forecasts and analyst forecasts: Evidence from mandatory disclosure system

Yutao Wang,Yunsen Chen,Juxian Wang

School of Accountancy,Central University of Finance and Economics,China

Management earnings forecasts and analyst forecasts: Evidence from mandatory disclosure system

Yutao Wang*,Yunsen Chen,Juxian Wang

School of Accountancy,Central University of Finance and Economics,China

A R T I C L EI N F O

Article history:

Accepted 25 September 2014

Available online 8 January 2015

JEL classification:

G14

G20

M41

Management earnings forecasts

Selective disclosure

Analyst forecasts

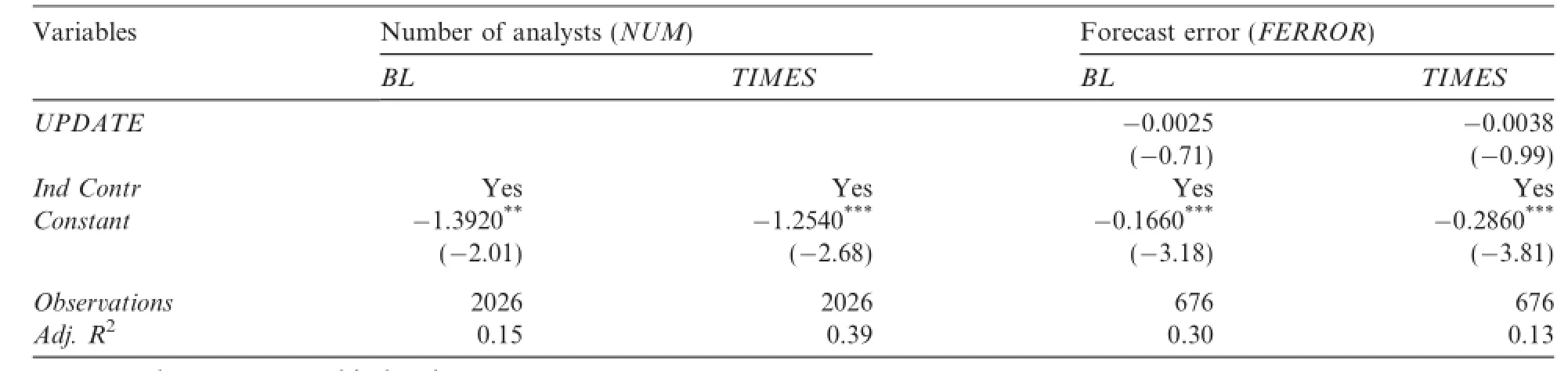

Distinct from the literature on the effects that management earnings forecasts (MEFs)properties,such as point,range and qualitative estimations,have on analyst forecasts,this study explores the effects of selective disclosure of MEFs. Under China’s mandatory disclosure system,this study proposes that managers issue frequent forecasts to take advantage of opportune changes in predicted earnings.The argument herein is that this selective disclosure of MEFs increases information asymmetry and uncertainty,negatively influencing analyst earnings forecasts.Empirical evidence shows that firms that issue more frequent forecasts and make significant changes in MEFs are less likely to attract an analyst following,which can lead to less accurate analyst forecasts.The results imply that the selective disclosure of MEFs damages informationtransmissionandmarketefficiency,whichcanenlighten regulators seeking to further enhance disclosure policies.

©2014 Production and hosting by Elsevier B.V.on behalf of China Journal of Accounting Research.Founded by Sun Yat-sen University and City University of Hong Kong.

1.Introduction

Management earnings forecasts(MEFs)of listed companies can reduce information asymmetry and the cost of capital,improving the efficiency of resource allocation in the capital market.Since 2001,regulators have constantly changed policies to promote and perfect the management forecast system in the Chinese capital market.A firm’s management must release earnings forecasts when they anticipate that the firm’sperformance may fluctuate or deviate significantly from preliminary expectations.This provides investors with more timely information and reduces information asymmetry in the capital market.The literature tends to focus either on the institutional background of voluntary management forecasts or on the alternative MEF types(e.g.,Libby et al.,2006;Wang and Wang,2012).However,few studies explore the effects of MEFs on analyst earnings forecasts(AEFs)under a mandatory system.This issue is especially important in China, as executives may make selective disclosures opportunistically under the mandatory system.The selective disclosure of MEFs may not be consistent with the regulation’s original intention,thus whether and how MEFs are selectively disclosed influence the behavior of market participants,making them important but rarely addressed questions.This study fills this gap by investigating MEFs’effects on analyst forecasts.

Under the existing mandatory management forecast system,as long as predicted performance reaches the required threshold,managers must disclose their earnings forecasts.Although the system is mandatory,managers have some selectivity in their choices that allow them to strategically maximize their own benefits before the actual earnings are disclosed in an annual report,such as selecting a certain management forecast form (qualitative or quantitative,point or range estimation).Some studies investigate how the types of MEFs affect the behavior of securities analysts,such as Libby et al.(2006)and Wang and Wang(2012).In contrast,this study focuses on the important issues of forecast frequency and significant changes.A significant change in a forecast is defined as managers making opposite forecasts in multiple MEFs,such as from loss to profit or from profit to loss.The selective disclosure of MEFs,such as multiple forecasts and significant forecast changes,is common in China’s capital market.For example,the listed firm“Green Earth”(stock code: 002200)forecast an increase in third-quarter earnings from 20%to 50%in 2009,then further revised the net profit range for 2009 downward to less than 30%in earnings forecasts made on January 30,2010.A net profit for 2009 of 62.12 million yuan was forecast in a preliminary earnings estimate on February 27, 2010,only to be corrected to a loss of 127.96 million yuan on April 28,2010.However,the earnings in 2009 were reported as a loss of 151.23 million yuan when the annual report was released on April 30, 2010.The company not only disclosed its earnings forecasts many times,but also changed their nature, prompting a significant change in earnings forecasts.

Management earnings forecasts aim to increase decision-related information for investors and reduce information asymmetry to reduce the cost of capital.As sophisticated investors,analysts rely on both public and private information to make earnings forecasts,and thus they are more sensitive to the quality and quantity of information.If a firm’s management selectively discloses MEFs,then analysts face greater information risk and uncertainty,which can result in them issuing less-accurate forecasts.Anecdotal evidence shows that MEFs are always a strong focus of financial analysts as a“prelude”to the annual financial statements of listed companies.1Analysts often use the earnings forecasts of listed companies to make forecast revisions and engage in further tracking.An example is DaYe Special Steel(000708),which published a positive profit alert for 2010 on January 24,2011,leading Guosen Securities to issue an analysis report based on the earnings forecast.They stated that the performance of beneficial equipment manufacturing was better than expected“the next day.”For details:http://stock.hexun.com/2011-01-25/127008640.html.As a channel of information transmission,MEFs provide more information and hence improve the quality of prediction for analysts(Libby et al.,2006).However,the error and uncertainty in MEFs may also affect analysts’forecast accuracy and dispersion(Barron et al.,1998;Zhang,2006).If a firm’s management makes a selective disclosure,such as multiple forecasts or significant forecast changes,the quantity and quality of analysts’access to public information changes,ultimately affecting their forecast quality.This study predicts that the selective disclosure of MEFs increases information uncertainty,causing analysts to change their subsequent decisions and thus reducing their forecast accuracy.The empirical results support this hypothesis and show that firms with greater forecast frequency and significant forecast changes are less likely to attract an analyst following and reduce analysts’forecast accuracy.

This study contributes to the literature in the following ways.First,it provides direct evidence of how selectively disclosing MEFs affects financial analysts’behavior.Previous studies mainly focus on the ways in which alternative MEF types influence analysts’forecasts.This study extends the research to include the economic consequences that selectively disclosing MEFs has on analysts’forecasts.Second,this study provides empirical evidence of the relationship between information disclosure and analyst behavior under an institutional background of mandatory MEFs.Unlike some mature capital markets,such as those in the United States,MEFs are mandatory in China.This study explores selective disclosure in a mandatory disclosure system to provide new empirical evidence of the relationship between MEFs and AEFs.Third,this study has important policy implications.It shows that the selective disclosure of MEFs,such as multiple forecasts and significant forecast changes,has a negative effect on AEFs.This indirectly affects investors’behavior and hence the effectiveness of the capital market,further destabilizing the Chinese capital market.If regulators focus only on system design and ignore execution efficiency,any regulatory effects will be superficial,implying that regulators should pay more attention to the effective implementation of MEF system,rather than perfecting the policy.

The rest of this study is organized as follows.Section 2 discusses the background and develops the hypotheses.Section 3 discusses the research design.Section 4 reports the empirical results and Section 5 concludes with a summary and a discussion of policy implications.

2.Institutional background and hypothesis development

2.1.Institutional background

The Chinese Securities Regulatory Commission(CSRC)oversees the Chinese capital market and delegates the authority to issue disclosure regulations to the stock exchanges.All Chinese companies end their fiscal years on December 31 and file quarterly,semiannual and annual financial reports with the stock exchanges. Before 1998,the CSRC did not stipulate a mandatory MEF system.Thus,investors in the capital market could not obtain comprehensive,timely information.This information asymmetry problem became an increasing concern for regulators and investors.In 1998,the CSRC enacted the requirement that listed firms suffering a loss in the previous three years or a large loss must disclose an earnings warning.This was the first time that the CSRC enacted a mandatory management forecast requirement,which was pivotal for China’s capital market.At the end of 2001,another requirement entitled,“Notice of Effectively Conducting Annual Report Disclosure Work of the Listed Firm”was implemented by both the Shenzhen and Shanghai Stock Exchanges.This notice required not only firms with anticipated fiscal-year losses,but also those with anticipated earnings increases or decreases,to issue mandatory management forecasts.This rule,however,only required listed firms to disclose forecasts within 30 calendar days of the end of the fiscal year,to increase information timeliness,because it is difficult to disentangle such forecasts from earnings preannouncements.2An earnings preannouncement is another way of disclosing earnings before the announcement of an annual report.

In 2002,significant changes were made in the requirements for MEFs.The CSRC confirmed the basic principle of“forecasting the next quarterly earnings in this quarterly report,”which meant that listed companies must make the forecast if a loss or a dramatic earnings increase or decrease was expected. Moreover,the“Notice of Effectively Conducting Annual Report Disclosure Work of the Listed Firm in 2002”required listed companies to make an immediate supplementary notice when necessary if they did not disclose a fiscal-year loss or a large change in earnings in the third-quarter or temporary reports,or if they did not report when their actual earnings differed from the forecasted earnings.Fundamentally,these requirements promote the timeliness of MEFs.More management forecasts are now made by listed firms in the fiscal year,narrowing the time gap between forecasts.More importantly,pre-forecast rather than post disclosure not only helps investors to understand earnings changes and make informed decisions,but also helps regulators to focus on firms with persistent abnormal accounting earnings changes.

In 2006,the CSRC began to require that listed companies with a loss the previous year and a profit the present year forecast their earnings.This requirement completed the MEF system.Until 2006,the mandatory MEF system required all listed firms to make an earnings forecast in the third-quarter report or a temporary announcement in the event of a loss,when a loss became a profit or when earnings increased or decreased more than 50%in one fiscal year.

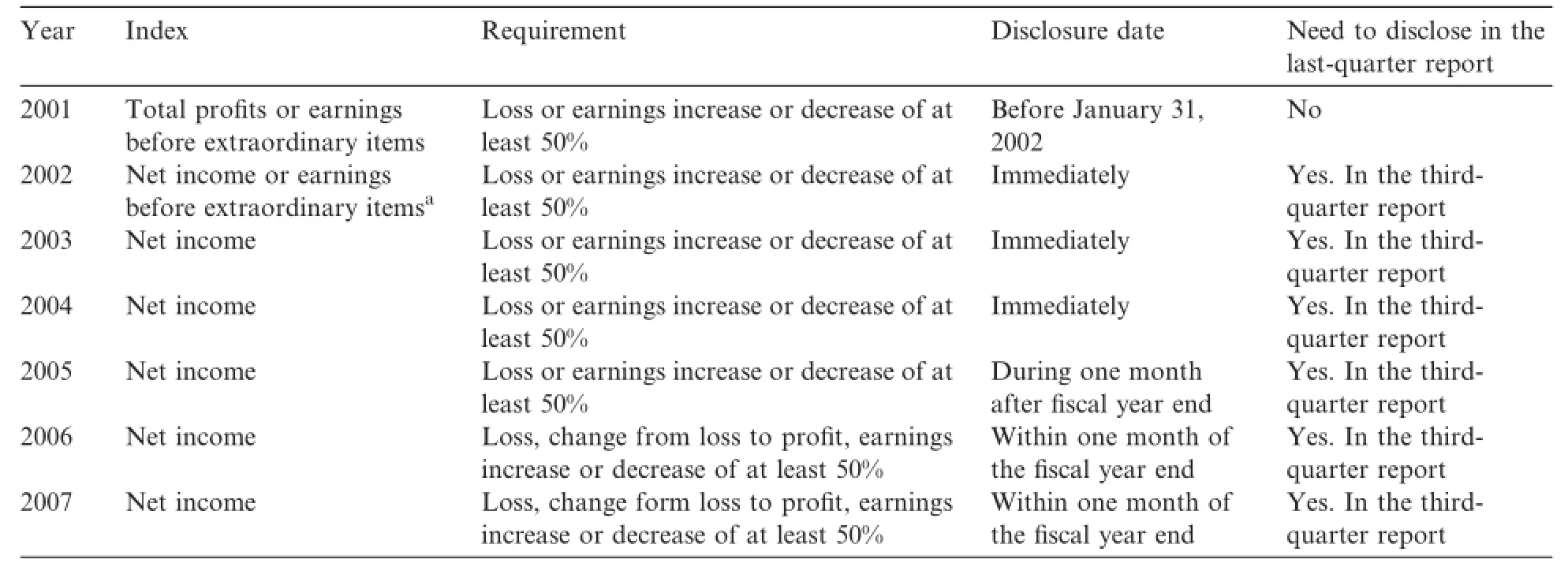

Similar to the literature,this study only focuses on the MEFs of annual earnings,not including semi-annual earnings.Table 1 lists the changes in the MEF system made by the Shenzhen and Shanghai Stock Exchanges during 2001–2007.3We do not analyze the management forecast system after 2007 because it changed from mandatory to voluntary disclosure.The sample thus covers the 2001–2007 period.

Table 1 Regulation of management earnings forecasts in China:2001–2007.

Table 1 shows that the MEF system began changing gradually in 2001,but was not complete until 2007. First,the system only required firms to disclose a loss in 2000.Beginning in 2001,firms with a loss or earnings increases or decreases of at least 50%were all required to make a disclosure.Beginning in 2006,firms sustaining a change from a loss to a profit or vice-versa joined the list of those required to disclose.Hence, the Chinese MEF system was improved gradually.Second,the indices used in this system have become increasingly stable and reasonable.Between 2001 and 2002,firms could choose between net income(and total profit)and earnings before extraordinary items as the benchmark.After 2002,however,net income was used exclusively.Such regulation changes can improve the relevance and usefulness of earnings forecast information,which is the main concern for investors.Third,listed firms are now required to make more timely MEF disclosures.Unlike in previous years,the recent regulation requires a firm’s management to disclose their earnings forecasts not only within one month of the fiscal year end,but also in the third quarter report. The present-day MEF system provides more timely and unambiguous accounting information to market participants,thus mitigating the information asymmetry between firms and investors.

2.2.Hypothesis development

Managers can usually decide whether,when and what to disclose to outside investors when maximizing stockholders’wealth or their private benefits(Hirst et al.,2008).The literature on voluntary MEF environments investigates the influence of management earnings disclosures from an information transmission perspective.For example,Skinner(1994)finds that firms disclose bad news through earnings forecasts to avoid litigation risk.Kothari et al.(2009)note that managers prefer to disclose good news earlier than bad news for career consideration reasons.Matsumoto(2002)finds that managers make earnings forecasts to decrease analysts’forecasts and mitigate the market reaction to bad news.Frankel and McNichols(1995) and Lang and Lundholm(2000)argue that firms disclose information more frequently and disclose more good news when they seek re-financing from outsiders.These studies show that in a voluntary disclosure environment,managers have an incentive to influence investor behavior to achieve specific goals.Given management’s rational economic perspective,they often disclose financial or non-financial information selectively or opportunistically to maximize their own benefits rather than those of outside investors.

It can be inferred that China’s mandatory MEF system forces managers to disclose MEFs once the subsequent predicted annual earnings reach a specific threshold,but managers can still use their disclosure behavior,such as alternative forms,forecast frequency or significant forecast changes to maximize their benefits.Because managers have information advantages over outside investors,it is very difficult for the latterto judge the reliability of MEFs,and they can be easily misled by managers with opportunistic incentives.This study investigates two typical MEF disclosure practices in China’s mandatory MEFs system:multiple forecasts and significant forecast changes.Multiple forecasts are defined by the disclosure numbers of MEFs for annual earnings and significant forecast changes are when managers release opposite earnings forecasts over at least two forecasts.For example,a manager might predict that the subsequent annual earnings will increase at least 50%from the previous year in one forecast,and in the next forecast the predicted earnings are revised to reflect at least a 50%decrease.This study investigates these selective MEF practices and their influence over analysts’forecasts.

As sophisticated investors,analysts rely on both public and private information to form their own forecasts.Previous studies investigate whether and how public information,such as annual reports,segment reports and management earnings forecasts,affect analysts’forecast properties(e.g.,Baldwin,1984; Hodder et al.,2008;Langberg and Sivaramakrishnan,2008;Libby et al.,2006).In the research on MEFs, early studies consistently find that MEFs are associated with statistically significant stock price reactions (e.g.,Ajinkya and Gift,1984;Penman,1980;Waymire,1984),which strongly suggests that MEFs provide new information not previously reflected in investors’beliefs about firms’earnings prospects.Based on these findings,Waymire(1986)further examine the relative accuracy of analyst earnings forecasts prepared both before and after(prior and posterior forecasts)voluntary MEFs,with the following primary results:(1) management forecasts are,on average,more accurate than analysts’forecasts prepared before management forecasts and(2)analysts’forecasts prepared after management forecasts are no more accurate than MEFs. These observed accuracy differences imply that managers hold inside information upon forecast release.These studies and findings on stock price reactions and analyst forecast behavior strongly suggest that MEFs provide new information related to firms’earnings prospects that financial analysts then absorb into their decision processes.Subsequent studies focus on the alternative MEF types,bias in MEFs and how managerial behavior influences analysts’forecasts.For example,Skinner(1994)and Libby et al.(2006)investigate the effects of point and range earnings forecasts and find that while forecast types do not have an immediate effect after performance disclosure,once the actual results have been released,the performance forecast form does affect analysts’forecasts.Tan et al.(2010)investigate whether and how biased MEFs influence analysts’forecasts. Specifically,they examine how analysts’incentives interact with the consistency and magnitude of bias in management’s guidance when determining the extent to which analysts’adjust their earnings estimates for the known bias.Experiments show that analysts do not adjust their forecasts to account for managers’tendency to provide downwardly-biased guidance,even though they are aware of this tendency(Hun-Tong et al.,2002),and the findings are ascribed to analysts’belief that maintaining a good relationship with management matters in the post-regulation fair disclosure environment.

Given the aforementioned studies,financial analysts rely on MEFs to make their forecasts.Although MEFs are mandatory in China’s market,management can make other selective choices,such as making multiple forecasts or significant forecast changes.This selective disclosure of MEFs exaggerates information uncertainty,making it more difficult for analysts to make informed decisions about processing this public information.Hence,MEFs significantly influence analysts’forecasts.Zhang(2006)investigates the relationship between information uncertainty and AEFs and finds that greater information uncertainty leads to larger forecast errors.Thus,it is reasonable to believe that the selective disclosure of MEFs increases information uncertainty,negatively affecting AEFs.

In summary,a negative association between the selective disclosure of MEFs and analysts’forecasts is expected,and the hypotheses are as follows.

H1.Selective MEFs(forecast frequency and significant forecast changes)have a negative effect on AEFs.

This study focuses on the two properties of analysts’forecasts:analyst following and forecast accuracy; hence,H1 is divided into the following sub-hypotheses.

H1a.Firms with more frequent forecasts or significant forecast changes are less likely to have an analyst following.

H1b.Firms with more frequent forecasts or significant forecast changes exhibit inferior AEF accuracy.

3.Research design

3.1.Empirical model and variable definitions

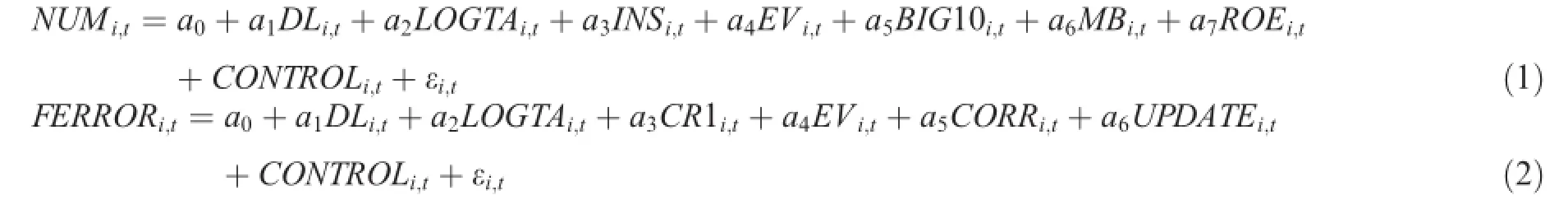

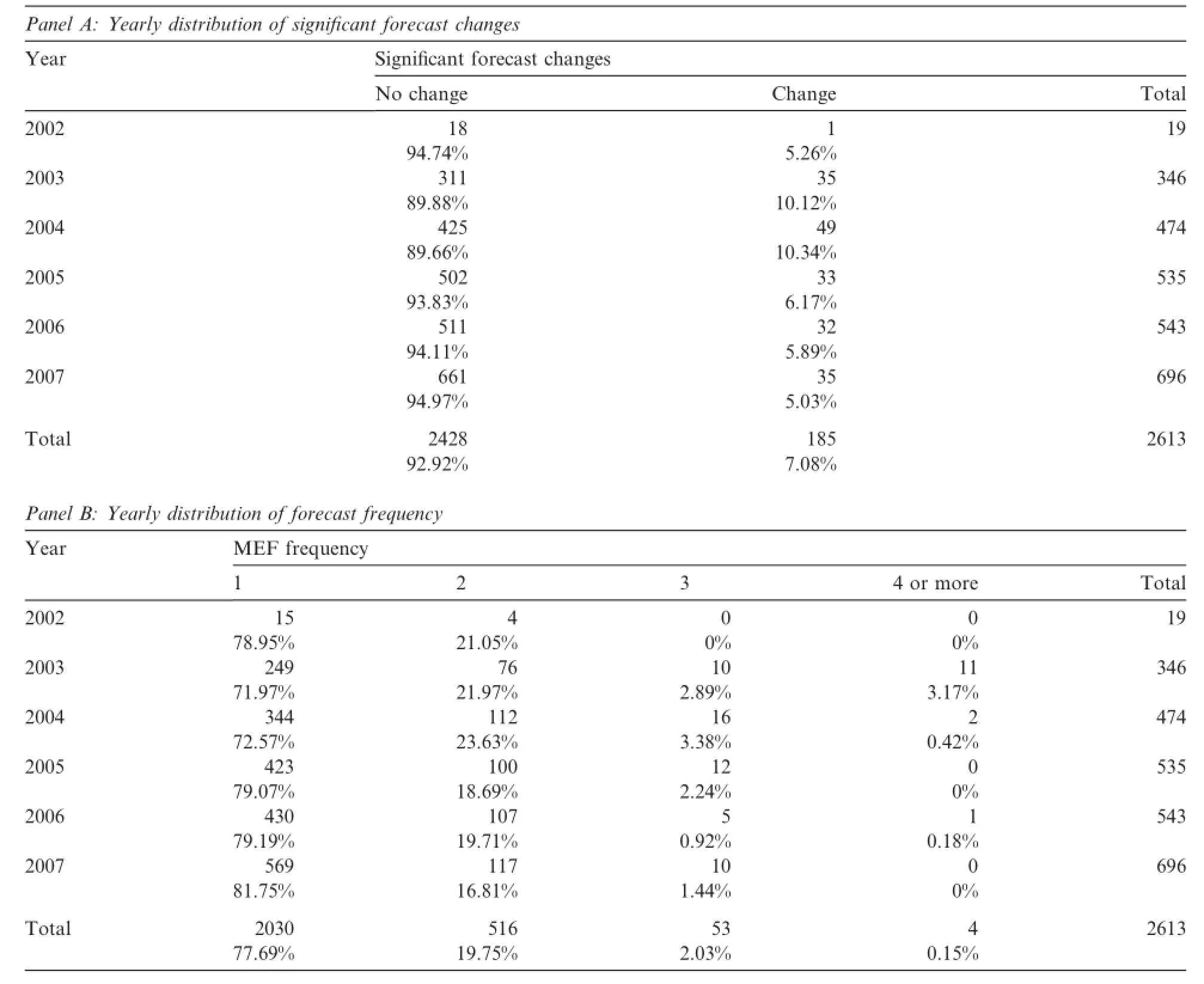

To investigate the effect of MEFs on analysts’forecasts,analyst following and forecast accuracy are used as the dependent variables and the following regression models are used to test the hypotheses.

where FERRORi,t=ABS[Mean(Fnetproi,t)-Netproi,t]/Tvali,trefers to analyst forecast accuracy.This measure captures the magnitude of the difference between analyst forecast earnings(Fnetpro)and actual earnings(Netpro).NUM is defined as the number of analysts following firm i in year t.The main variable of interest is DLi,t, which reflects the selective disclosure of MEFs and is divided into two variables:TIMEs and BL.Multiple forecasts(or forecast frequency)of MEFs is TIMEs,measured as MEF frequency.A significant forecast change is BL,an indicator that equals 1 if the current MEF is revised to oppose the previous one,and 0 otherwise.Citing previousstudies(e.g.,Bai,2009;WangandWang,2012),otherfactorsaffectinganalysts’forecastsarecontrolled for.LOGTA is firm size,such that a larger firm size results in a greater analyst following,more available information and lower analyst forecast error.INS is the holding ratio of institutional investors,such that a higher holdingratioresultsinbetterinstitutionalinvestorsupervisionofselective disclosure,ahigherlikelihoodofanalyst following and lower analyst forecast error.EV refers to earnings volatility and is calculated as the standard deviationofearningsduringthepreviousthreeyears,dividedbytheabsolutevalueofthemeanofthe3-yearearnings.Itispredictedthathigherearningsvolatilitywillresultinasmallerlikelihoodofanalystfollowingandlower forecastaccuracy.BIG10 refersto auditingqualityand isequal to 1 ifthe auditor isamong the 10 largest auditor firms according to client assets.MB is firm growth,calculated as the ratio of market valueto book value.ROE is earnings divided by net equity.CORR refer to the credibility of earnings information,calculated as the correlation coefficient between accounting earnings and annual stock returns.UPDATE refers to the frequency with which forecasts are updated by brokers,measured as the total number of all analyst reports for firm i in year t,divided by the number of brokers following the firm.All of the variable definitions are summarized in Table 2.

Table 2 Variable definitions.

3.2.Sample selection

The initial sample includes all of the MEFs for annual earnings released by A-share listed companies from 2001 to 2007.First,MEFs issued after April 30 the following year are dropped.Second,ambiguous MEFs are deleted.Third,firms issuing only B-stocks are dropped.Finally,firms in the financial industries are excluded. The remaining sample includes 3975 firm-year observations.For the analyst forecasts sample,because every analyst is capable of making multiple forecasts for a firm in a specific year,the most recent forecast for each analyst is kept.Second,the number of analysts following and analyst forecast errors based on firm year are calculated.Finally,after merging the MEF and AEF samples and excluding the observations with missing values for the control variables in the regressions,2613 firm-year observations are retained.Table 3 reports the sample selection procedure.The data on MEFs are from the WIND dataset and AEFs and other financial data are from the CSMAR dataset.

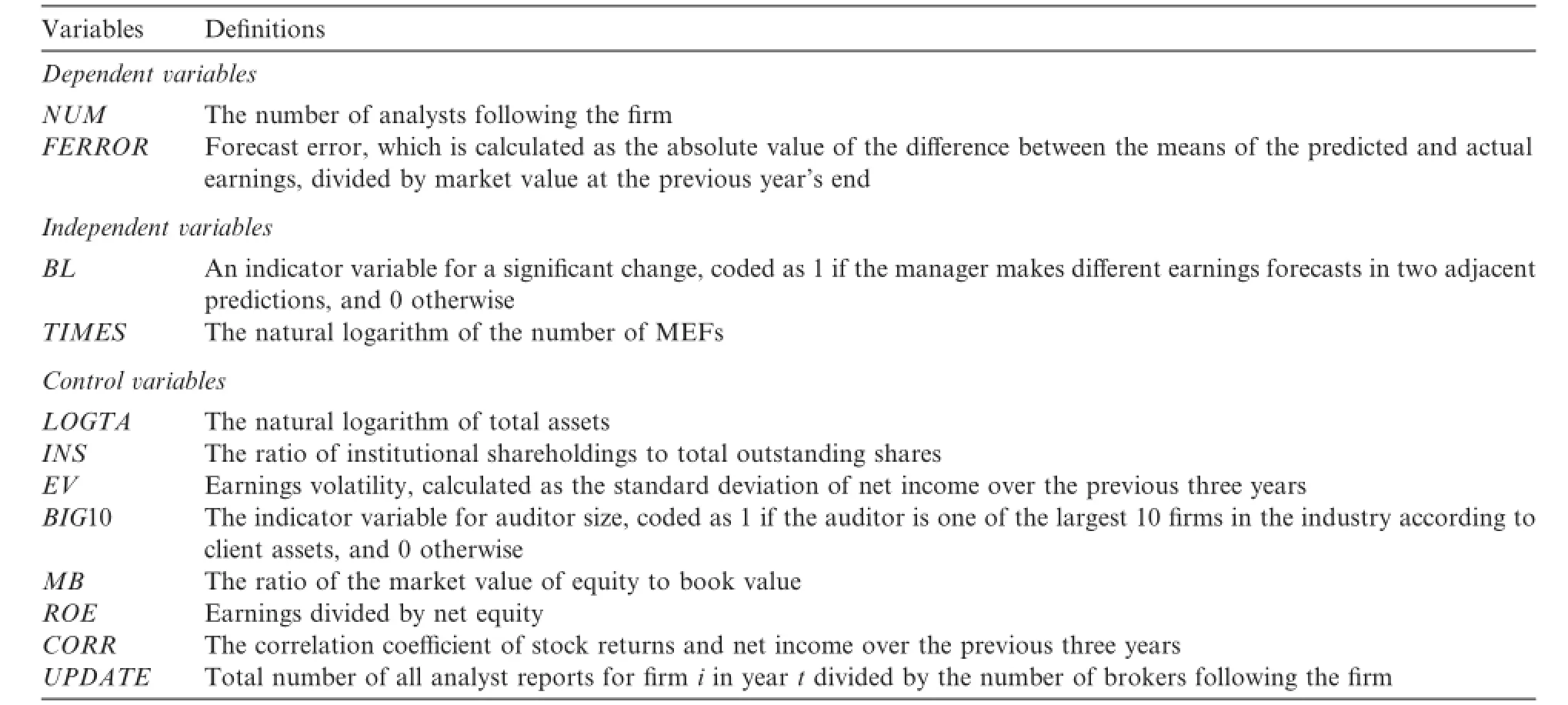

Table 4 lists the yearly distributions of significant forecast changes and forecast frequency in Panels A and B,respectively.4Table 4 only lists the yearly distributions from 2002 and deletes observations in 2001,which is due to missing analyst following data.Panel A shows that the ratio of significant forecast changes decreased from 10.12%in 2003 to 5%in 2007.Panel B shows that firms with one MEF increased from 71.97%in 2003 to 81.75%in 2007.In contrast,firms with two MEFs decreased over the period.These results imply that the improvement and strengthening of the MEF system weakened selective MEF disclosure.

4.Empirical analysis

4.1.Descriptive analysis

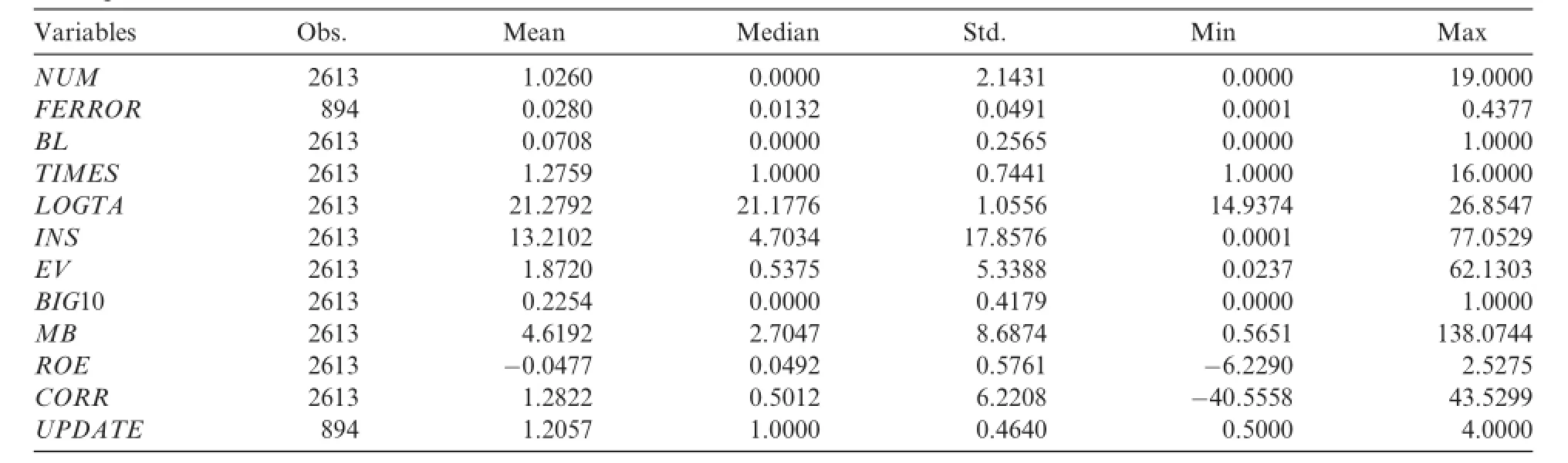

Table 5 shows the summary statistics for the main variables used in the analysis.The mean value of FERROR is 0.0280,which means that the difference between the average forecast earnings and actual earnings accounts for 2.8%of the year-end market value.NUM is the number of analysts following a firm in a year, which indicates that on average,every firm has at least one analyst following it with a maximum of 19 followers.The mean value of BL is 0.078,which means that between 2002 and 2007,about 7%of firms changed their earnings forecast dramatically.The mean value of TIMES is 1.27,which means that on average, each firm makes at least one earnings forecast.

4.2.Univariate tests

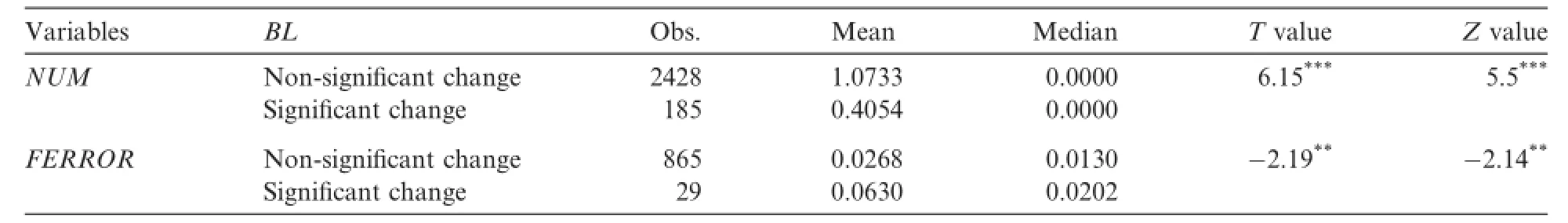

Table 6 reports the univariate test results for significant forecast changes.Based on the two groups,with and without significant forecast changes,Table 6 shows that firms with significant changes have lower analysts following(0.4054 vs 1.0733 for mean and 0.000 vs 0.000 for median)and higher forecast errors(0.063 vs0.0268 for mean and 0.0202 vs 0.0130 for median).The t-tests and Wilcoxon tests reveal a significant difference between these two groups,thus the univariate tests support our hypotheses.

Table 4 Yearly distributions of managers’selective earnings forecast disclosures.1

Table 5 Descriptive statistics.

Table 6 Univariate tests of significant forecast changes.

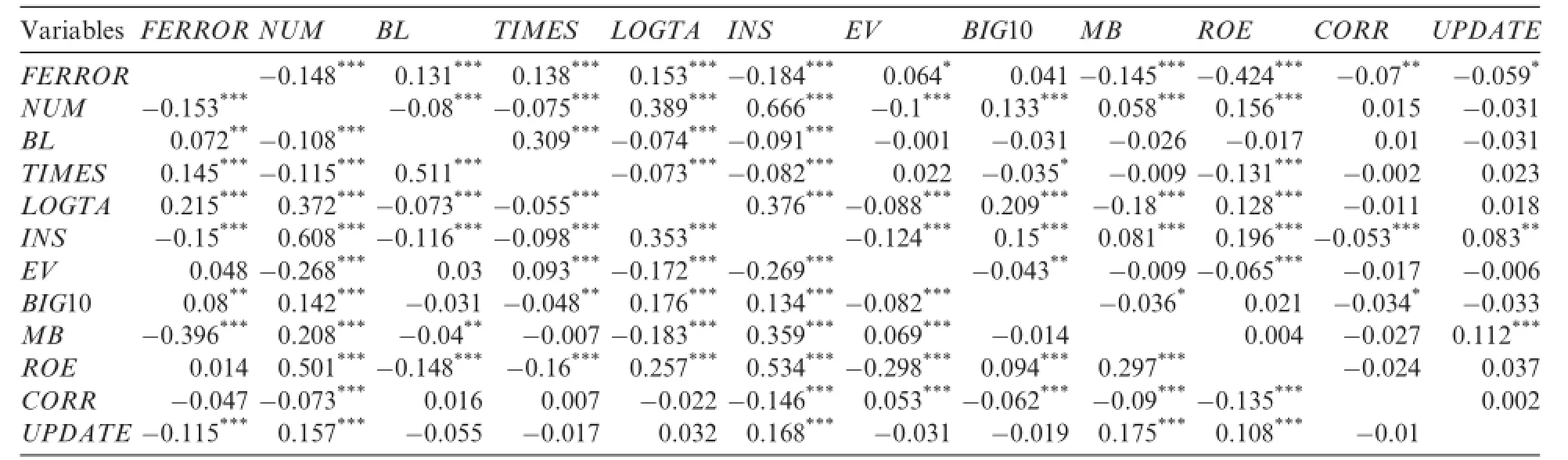

Table 7 reports the correlation coefficient matrix and shows that TIMES has a significant negative (positive)correlation with NUM(FERROR)at the 1%level.This indicates that a higher MEF frequency is associated with a smaller analyst following and a higher forecast error.This finding is consistent with our hypotheses.Table 7 also shows no notable associations among the other variables.

4.3.Multivariate tests

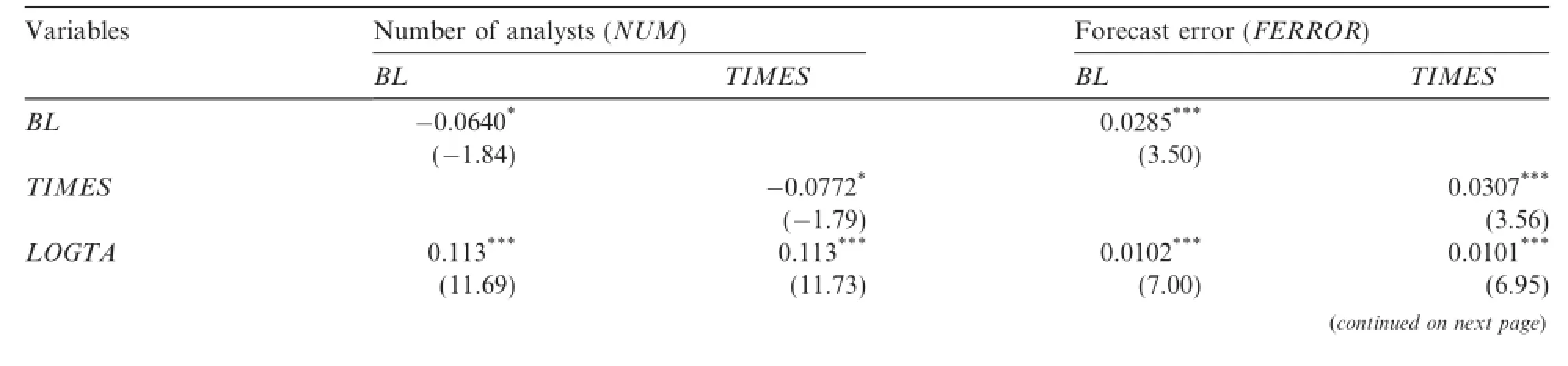

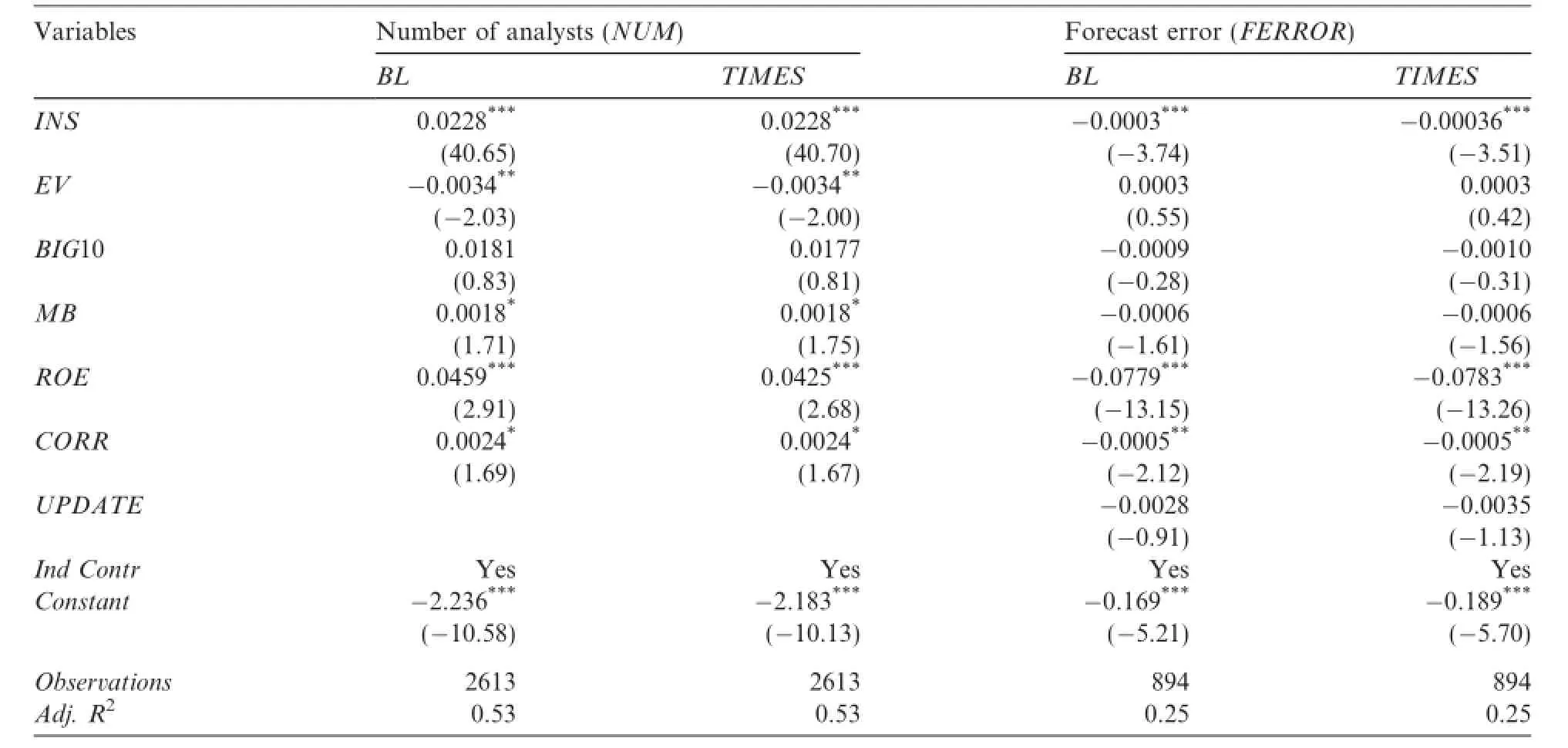

Based on Models(1)and(2),Table 8 reports the multivariate regression results.Consistent with the univariate analysis,firms with multiple forecasts and significant forecast changes experience a lower analystfollowing and higher forecast errors.Specifically,the coefficient on BL is significantly negatively related to NUM at the 10%level(coefficient=-0.064 with t=-1.84)and significantly positively related to FERROR at the 1%level(coefficient=0.029 with t=3.50).Meanwhile,the coefficient on TIMES is significantly negatively related to NUM at the 10%level(coefficient=-0.077 with t=-1.79)and significantly positively related to FERROR at the 1%level(coefficient=0.031 with t=3.56).Therefore,these results are consistent with our hypothesis that the selective disclosure of MEFs negatively influences analysts’forecasts.

Table 7 Coefficient correlation matrix.

Table 8 Relationship between managers’earnings forecasts and analyst forecasts.

Table 8(continued)

4.4.Additional analysis

The results show that the selective disclosure of MEFs increases the uncertainty of information for analysts, negatively influencing their forecasts.However,firms with a higher analyst following or forecast accuracy are less likely to experience selective MEF disclosure due to the outside governance from analysts.Hence,there is an endogeneity problem in the analysis.To mitigate this endogeneity issue and enhance the reliability of the results,a two-step regression based on the determination model is conducted.In the first step,the following model is constructed:

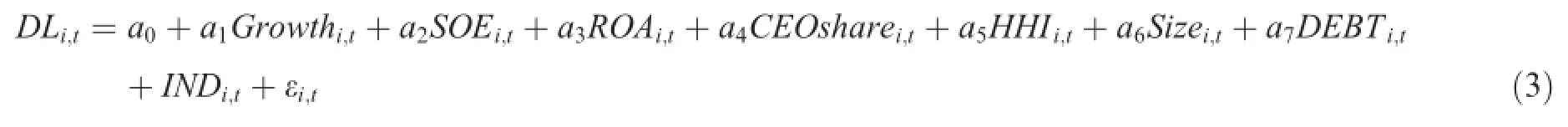

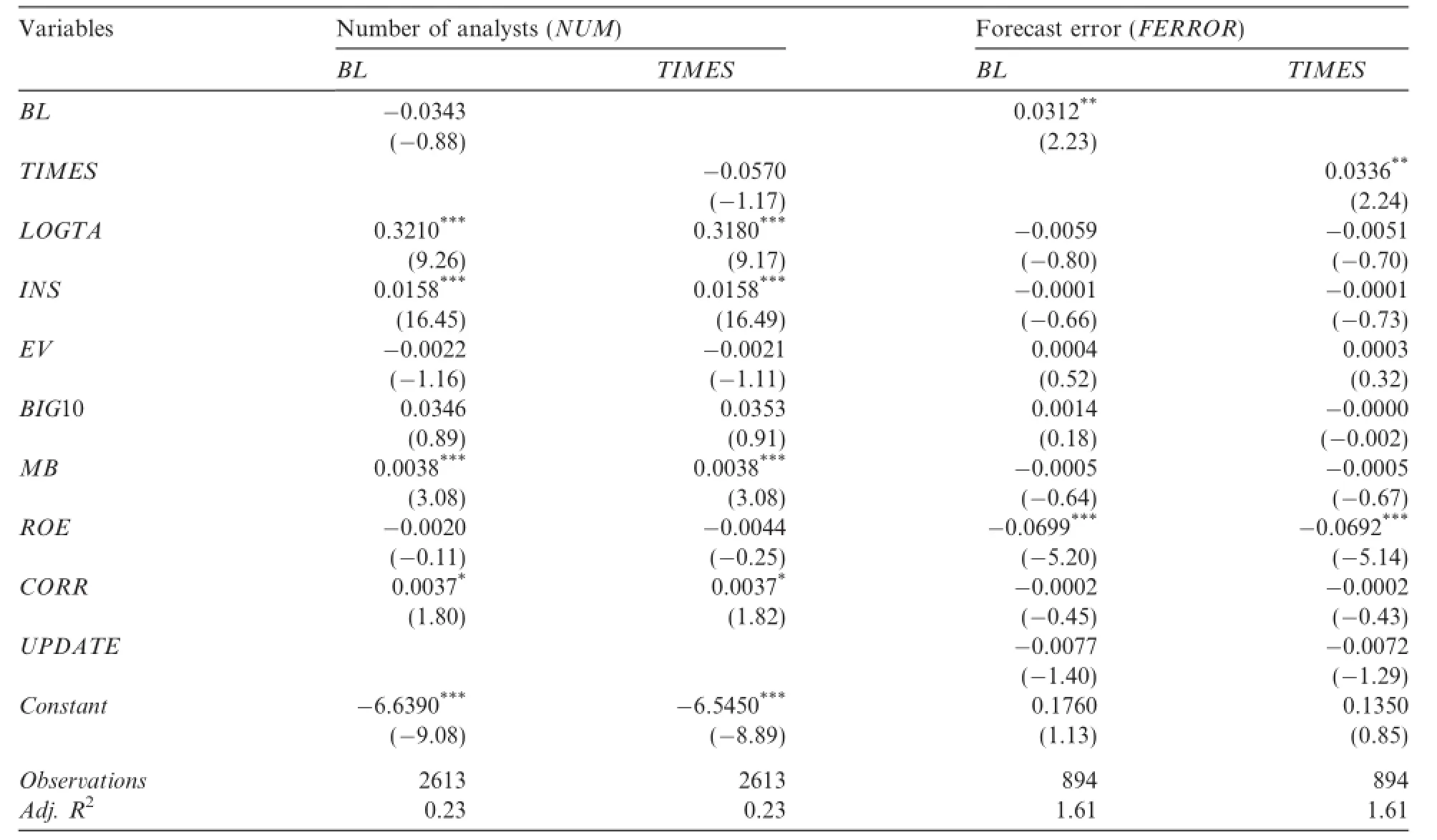

where DL refers to selective MEF disclosure,as measured by BL and TIMES.Growth indicates the difference in total assets between the present and previous year.SOE is the firm’s ownership,and equals 1 if the ultimate controller is the state,and 0 otherwise.ROA is return on total assets,which indicates the firm’s profitability.CEOshare is the proportion of shares held by the CEO,which represents insiders’incentives. HHI is the Herfindahl–Hirschman index,calculated as HHI=∑(Xi/X)2,where X=∑Xiand Xiis the sales of firm i.SIZE is measured as the natural logarithm of total assets.DEBT is the leverage of the firm and INDare industry dummy variables.The results based on Model(3)are listed in Table 9 and show that Growth, ROA and SIZE(DEBT)are(is)negatively(positively)related to BL and TIMES.Likewise,all four coefficients are significant in Columns(1)and(2)of Table 9,except for Growth and DEBT in Column(1).

Table 9 Determinants of management earnings forecasts.

Table 10 2SLS regression results.

Table 10(continued)

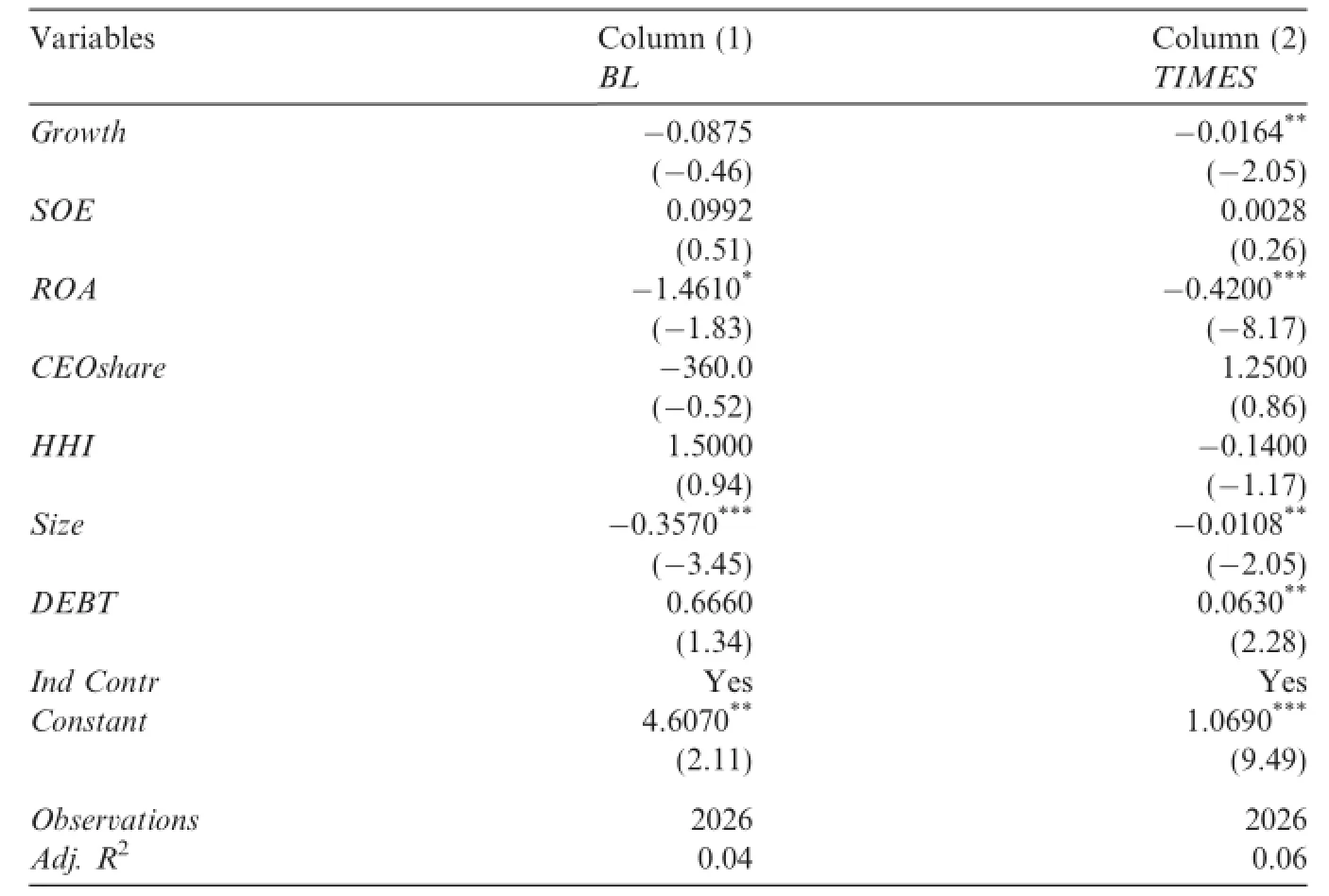

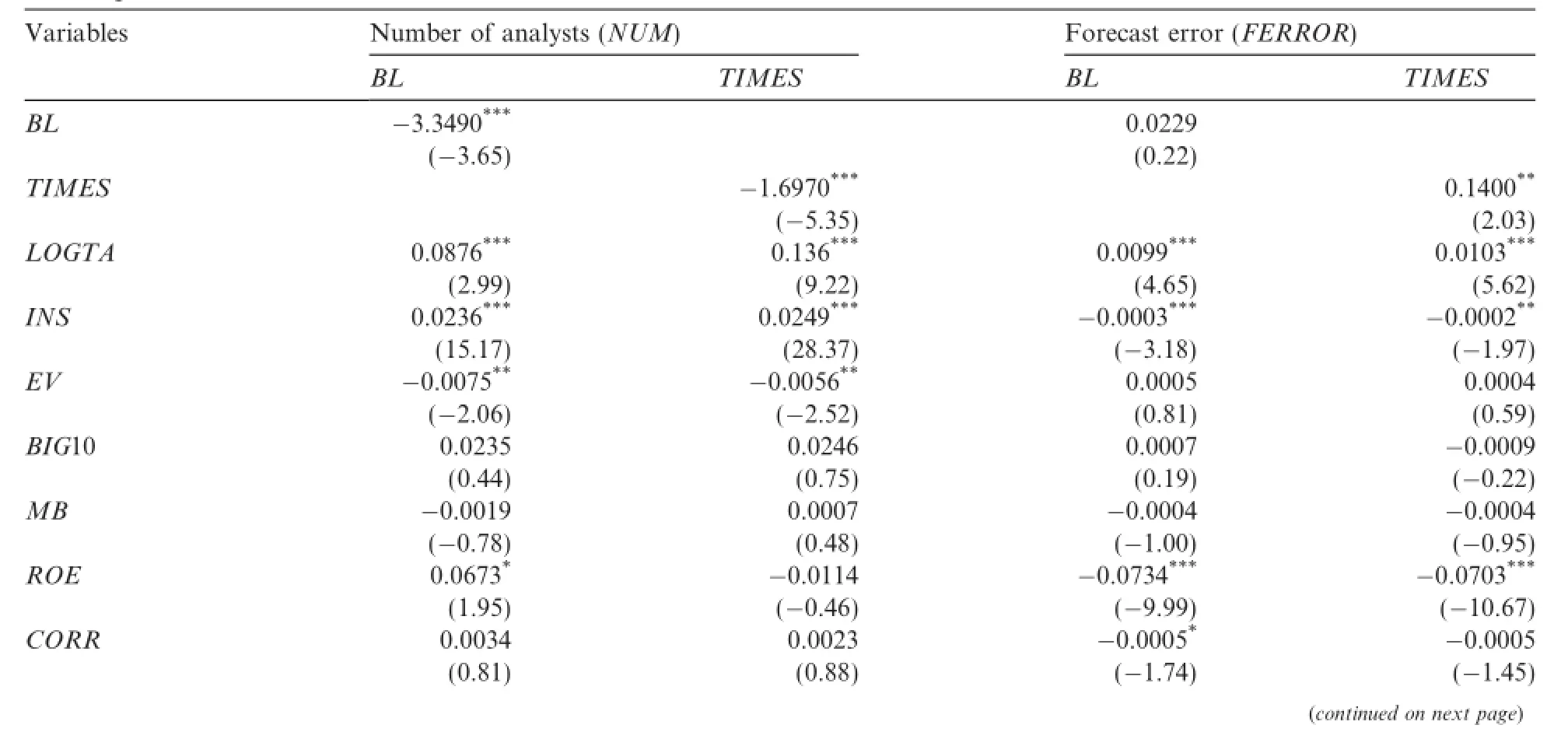

In the second stage,the predicted values of DL in Table 9 are incorporated into Models(1)and(2).The results are shown in Table 10,which shows that all of the results are consistent with our hypothesis,except that the coefficient of BL is no longer significant in the FERROR model.

4.5.Robustness tests

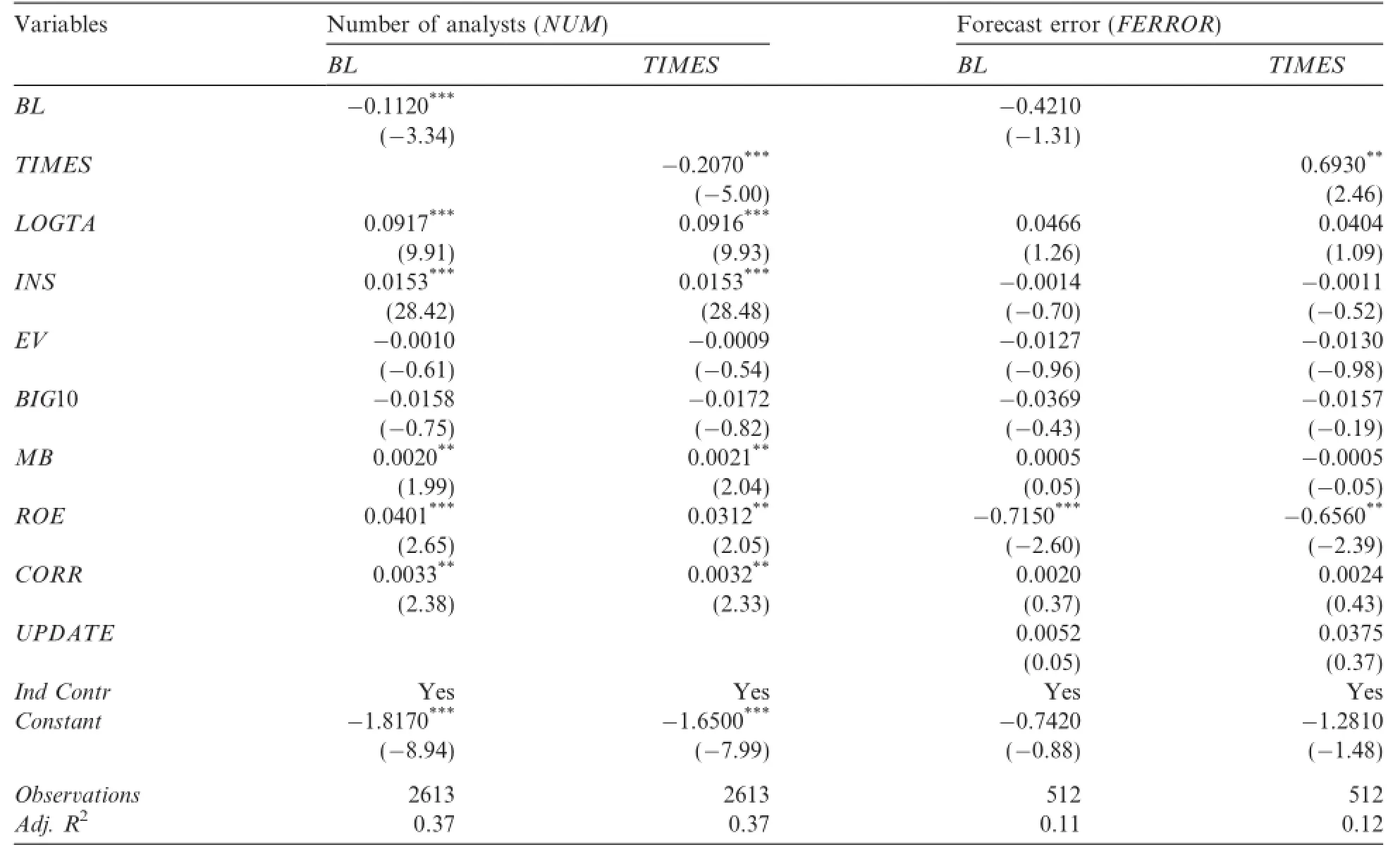

In addition to the main tests above,several robustness tests were conducted.First,the omitted variable problem is eliminated by controlling for firm fixed effects in the regression model.The results are shown inTable 11 and the findings are generally consistent with our hypothesis,except that BL and TIMES are no longer significant in the analyst following model.

Table 11 Robustness test(1):Fixed effects model.

Table 12 Robustness tests(2):Analyst forecast behavior after management earnings forecasts.

Second,the results may also be caused by simultaneity.Two methods are used to solve this problem.First, only analyst forecasts that were issued after MEFs disclosure are kept.This requirement reduces the final sample from 894 to 512.The results based on this sample(observations=512)are shown in Table 12 and are similar to those in Table 8.Second,BL and TIMES last year are used as the main explanatory variables and the untabulated results are also similar to those in Table 8.

Finally,the results may be driven by firm complexity.5We thank the referee for this suggestion.To control for this effect,several variables are selected to proxy for firm complexity,including intangible assets,accounts receivable,inventory and the sum of accounts receivable and inventory.The full sample is then divided into sub-samples to examine whether the results are consistent.The untabulated results show that there are no significant differences between the two sub-samples,indicating that the findings are not driven by firm complexity.

5.Conclusion

This study examines the association between selective MEF disclosure and analysts’forecasts under China’s mandatory MEF system.Two types of selective MEF disclosure and their effects on analysts’following and forecast accuracy are examined:forecast frequency and significant forecast changes.The empiricalresults show that such selective disclosure negatively influences analysts’forecasts and reduces analyst following and forecast accuracy.These results imply that in addition to MEF type,how and how frequently managers disclose MEFs also influence analysts’forecasts in mandatory MEF system,such as the one in China.

This study makes several important potential contributions to the literature and practice.First,MEFs are one of most important information sources for analysts’forecasts.This study examines the effect of managerial disclosure behavior on AEFs from an information uncertainty perspective.It also contributes to the literature on information disclosure quality(Lang and Lundholm,1996;Bai,2009;Langberg and Sivaramakrishnan,2008).Second,this study provides more empirical evidence illustrating the relationship between information uncertainty and analysts’behavior(Zhang,2006).Third,this study’s results have important policy implications.The empirical evidence shows that selective MEF disclosure negatively influences analysts’forecasts.Meanwhile,financial analysts are an important intermediary and they play a main role in mitigating the information asymmetry in the capital market.Thus,more resources should be devoted by regulators to supervise MEF disclosure in an effort to improve market efficiency.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank the executive editor and anonymous referees for their helpful suggestions.We would also like to thank Prof.Rui Oliver Meng,Su Xijia,Li Oliver,Chen Donghua in 2012 CJAR Summer Workshop at City University of Hong Kong.This study was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China(Project 71102124),grants from the Beijing Municipal Commission of Education“Pilot Reform of Accounting Discipline Clustering”,and grants from the Beijing Municipal Commission of Education“Joint Construction Project”.

References

Ajinkya,B.B.,Gift,M.J.,1984.Corporate managers’earnings forecasts and symmetrical adjustments of market expectations.J.Acc.Res. 22(2),425–444.

Bai,Xiaoyu,2009.The multiple influence of corporate disclosure policy on analyst forecast.J.Financial Res.4,92–112.

Baldwin,B.A.,1984.Segment earnings disclosure and the ability of security analysts to forecast earnings per share.Acc.Rev.59(3), 376–389.

Barron,O.E.,Kim,O.,Lim,S.C.,Stevens,D.E.,1998.Using analysts’forecasts to measure properties of analysts’information environment.Acc.Rev.73(4),421–433.

Frankel,R.,McNichols,M.,1995.Discretionary disclosure and external financing.Acc.Rev.70(1),135–150.

Hirst,D.E.,Koonce,L.,Venkataraman,S.,2008.Management earnings forecasts:a review and framework.Acc.Horizons 22(3),315.

Hodder,L.,Hopkins,P.E.,Wood,D.A.,2008.The effects of financial statement and informational complexity on analysts’cash flow forecasts.Acc.Rev.83(4),915–956.

Hun-Tong,T.,Libby,R.,Hunton,J.E.,2002.Analysts’reactions to earnings preannouncement strategies.J.Acc.Res.40(1),223–246. Kothari,S.P.,Shu,S.,Wysocki,P.D.,2009.Do managers withhold bad news?J.Acc.Res.47(1),241–276.

Lang,M.H.,Lundholm,R.J.,2000.Voluntary disclosure and equity offerings:reducing information asymmetry or hyping the stock? Contemp.Acc.Res.17(4),623–662.

Lang,M.,Lundholm,R.,1996.The relation between security returns,firm earnings,and industry earnings.Contemp.Acc.Res.13(2), 607–629.

Langberg,N.,Sivaramakrishnan,K.,2008.Voluntary disclosures and information production by analysts.J.Acc.Econ.46(1),78–100.

Libby,R.,Hun-Tong,T.,Hunton,J.E.,2006.Does the form of management’s earnings guidance affect analysts’earnings forecasts?Acc. Rev.81(1),207–225.

Matsumoto,D.A.,2002.Management’s incentives to avoid negative earnings surprises.Acc.Rev.77(3),483–514.

Penman,S.B.,1980.An empirical investigation of the voluntary disclosure of corporate earnings forecasts.J.Acc.Res.18(1),132–160.

Skinner,D.J.,1994.Why firms voluntarily disclose bad news.J.Acc.Res.32(1),38–60.

Tan,H.,Libby,R.,Hunton,J.E.,2010.When do analysts adjust for biases in management guidance?Effects of guidance track record and analysts’incentives.Contemp.Acc.Res.27(1),187–208.

Wang,Yutao,Wang,Yanchao,2012.Does earnings preannouncement information impose effects on the forecast behavior of financial analysts?J.Financial Res.6,193–206.

Waymire,G.,1984.Additional evidence on the information content of management earnings forecasts.J.Acc.Res.22(2),703–718.

Waymire,G.,1986.Additional evidence on the accuracy of analyst forecasts before and after voluntary management earnings forecasts. Acc.Rev.61(1),129.

Zhang,X.F.,2006.Information uncertainty and analyst forecast behavior.Contemp.Acc.Res.23(2),565–590.

29 October 2012

at:School of Accountancy,Central University of Finance and Economics,No.19,Haidian South District, Beijing 100081,China.

E-mail addresses:wangyutao@cufe.edu.cn(Y.Wang),chenyunsen@vip.sina.com,yschen@cufe.edu.cn(Y.Chen),gocontinue@163. com(J.Wang).

http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.cjar.2014.09.001

1755-3091/©2014 Production and hosting by Elsevier B.V.on behalf of China Journal of Accounting Research.Founded by Sun Yat-sen

University and City University of Hong Kong.

China Journal of Accounting Research2015年2期

China Journal of Accounting Research2015年2期

- China Journal of Accounting Research的其它文章

- The effect of stock market pressure on the tradeoff between corporate and shareholders’tax benefits

- Monetary policy and dynamic adjustment of corporate investment:A policy transmission channel perspective

- Short sellers’accusations against Chinese reverse mergers:Information analytics or guilt by association?☆

- Guidelines for Manuscripts Submitted to The China Journal of Accounting Research