THE TURKIc cULTURE OF THE INNER TIANSHAN: THE LATEST INFORMATION

Kubatbek Tabaldyev

THE TURKIc cULTURE OF THE INNER TIANSHAN: THE LATEST INFORMATION

Kubatbek Tabaldyev

In the middle of the first millennium BcE, as the First Turkic Khanate and other unions were founded and nomadic Turkic tribes sPread across the vast territory of Eurasia, the first monuments of ancient Turkic culture were erected. Among these are tombs with fences and balbals, horse burials, and monuments with Turkic inscriPtions. The cultural heritage of the medieval Turkic PeoPle of Tien-Shan (Tianshan) was enriched by their works of art, mostly massive rock Paintings with engraved images of warriors (archers).

In the years 1998-2006, in the course of archaeological excavations in the south-eastern Part of the Kochkor valley conducted by teams from Kyrgyz State University, the American University of central Asia, and Kyrgyz-Turkish “Manas” University under the direction of K. Sh. Tabaldyev, a comPlex of ancient Turkic inscriPtions and rock arts was found and investigated. According to the content of the discovered art, we can assume that the image of a warrior riding a horse was a central motif in the Turkic rock arts of that Period (Figs.1-3). Hunting scenes Provided the background of these images. The rock art of this Period was more detailed than that of the earlier Period, and in it one can see new images such as tribal signs (tamgas). The images in the rock art of Persons and animals were Portrayed accurately with details shown, and their motions and gestures were highlighted, suggesting that the artist wanted to share his exPressions.

At the same time, new details in images were discovered, and some are followed by ancient Turkic inscriPtions which Provide further information. Dominant motifs were often rePeated and at Kok-Sai four examPles of an image of an equestrian figure holding a bird were discovered. DesPite the difference in size, these are all engraved using a similartechnique, and two of these images were followed by the same text. The style of the inscriPtions and the same tribal tamga evidence suggest that the artists who executed these works were from the same tribe or that these rock carvings were made by the same artist.

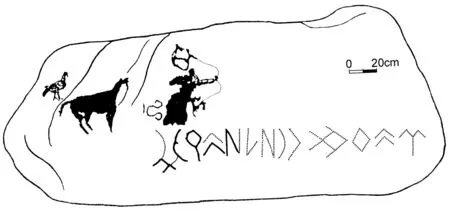

cultural tradition guided artists in choosing massive stones for the full realization of the images and texts they Planned. The Presence of funeral and memorial monuments of the Turkic Period at Kok-Sai Provides clear evidence of the significance of this territory for the sPiritual culture of the On Ok tribe (of the “Western Turks”). It is clear that the Kok-Sai comPlex served as a model for sacred outdoor Places. The examPles of rock art found in the Kochkor valley differ in their dimensions. One rock art work from Böirök-Bulak, for examPle, measures 3.80m by 1.75m. It Portrays an equestrian figure with a bird on his hand; there is also a tall bird which resembles a flamingo, as well as a grouP of other birds (Partridge, duck). The image of the rider measures 173cm by 168 cm; the tall bird, 90cm by 57cm; the other birds, 50cm by 37cm (see Fig. 1). The rider is Portrayed with a Pointed headdress, and the bird is on his left hand. The bird on the rider’s hand also differs from the other birds in that it has a shorter tail as well as a stirruP. The stirruP has rhomboid decorations.

The massive dimensions of the rock art from Böirök-Bulak, the detail of the images, and the meaning of the accomPanying text all indicate the nobility of the Person Portrayed in the work. According to the translation, this rock art was carved in honor of a man named Adyk (“Bear”), who could have been one of the leaders of the On Ok tribe.

These rock art works dePicting riders holding birds from the south-western Part of the Kochkor valley can be regarded as illustrating some tradition associated with the death of a Person. Some scholars who have conducted research on the rock art images of riders holding birds are of the same oPinion.[1]They have noted the relationshiP between the Portrayal of birds and the accomPanying texts in which the words “to fly (away)” and “to die” seem to be associated. In the monuments of Mongolia erected after the death of khans and even Kul-Tegin, death is exPressed by the word “иcha-bardy” (“he flew away”) – Kul-Tegin flew away in the Year of the Ram.[2]

The word “fly away” signified ascension to the heavens where the deceased would continue to exist.[3]The Kyrgyz PeoPle use the word “to fly away” as a synonym for the word“to die”. The mourning memorials in honor of deceased males contain the words “As a bird, he flew from my hands”. Such texts could also comPare a man to a bird “He was cunning as a bird”, or “My tynar flew away”.[4]One of the cunning birds, the tynar was a successful hunter.

In Kyrgyz folklore, the death of a hero is comPared to a flight in the direction of theMoon or Sun:

Asmandagy ak shumkar White falcon in the sky

Altyn boosun uzuPtur Breaking golden stirruPs

Aidy karai syzyPtyr Flew to the moon

Kumush booluu ak shumkar Falcon with silver stirruPs

Kumush boosun uzuPtur Breaking silver stirruPs

Kundu karai suzuPtur Flew to the sun

In the Kyrgyz ePic Kиrmanbek, the Protagonist was fatally wounded by his enemies. After the arrival of his friend Akkan, the sPirit of Kurmanbek allegorically leaves his body in form of the bird.

Turkic rock art is often a resource for recreating traditions, details of clothing, and hairstyles. The Pointed headdresses we see in some rock art images are regarded by some scholars as helmets, but such headdresses could also have imitated the form of helmets. There are textual descriPtions of such headdresses and in one chinese text about the Kyrgyz, translated by N. Bichurin, a headdress similar to those aPPearing in rock art is described: “In the winter Adjo wears a sable hat, in summer a hat with a golden rim, conical at the toP and curved at the bottom….”[5]In another translation by N. V. Kuner we read: “In this kingdom all subjects have their heads uncovered and braid their hair. In winter they make hats of sable. In summer, they use gold to decorate their hats which are Pointed at the toP and curved at the bottom. The subjects of the khanate make hats of felt, but they are of the same cut as those of the nobles.”[6]According to medieval sources, the headdress described above is similar to the Kyrgyz national headdress called kalPak, which is PoPular among Kyrgyz and Kazakh PeoPle even today.

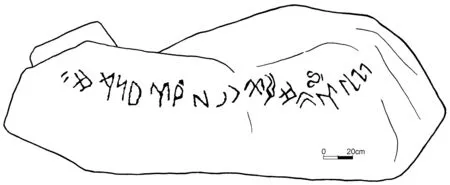

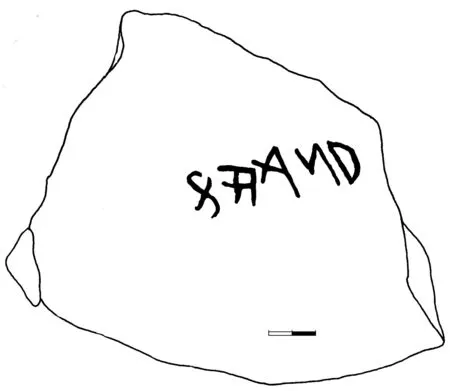

In the eastern Part of the Kochkor valley in the Kalmak-Tash area, there is an inscriPtion which reads “Er atym Bilge” (My heroic name is Bilge) (see Fig. 4), and this may have been one of the PoPular first names given to Turkic warriors. For examPle, we know of Bilge-khan, who was khan of the Eastern Turks and to whose son Suluk, the khan of the Turgesh PeoPle, gave his daughter. The most imPortant thing about this inscriPtion is that it was written from left to right, at variance to the usual Practice of arranging Turkic inscriPtions from right to left like Arabic. The rock art of Tien-Shan and that discovered earlier in Semirechie are both similar to that the Altai region, and over the last few years a series of Turkic inscriPtions in the graffiti style have also been found in Tien-Shan.[7]The Tien-Shan finds reflect theethnograPhic features of medieval central Asian Turkic PeoPles. Earlier equestrian images, as found at Kok-Sai and Böirök-Bulak, are less significant; later images are engraved in a more creative way as a Part of rituals in honor of the deceased. Evidence for this is Provided by the inscriPtion: “My name is Adyk, from the On Ok tribe, [my land is] Yarysh. I seParated [from there] at death.” (see Fig. 5) The rock art of the Western Turks is also more realistic in narrative comPosition.

The rock art tradition of the Turkic PeoPles of Tien-Shan develoPed, as was mentioned above, in the same direction as in other regions of central Asia, where the image of the equestrian warrior was widesPread. Praise of the image of the warrior-liberator, warrior-Parent, and warrior-chief continued through the sPiritual culture of Turkic language-sPeaking PeoPles. As a result the ePic of Manas was formed, reflecting the events of different historical ages.

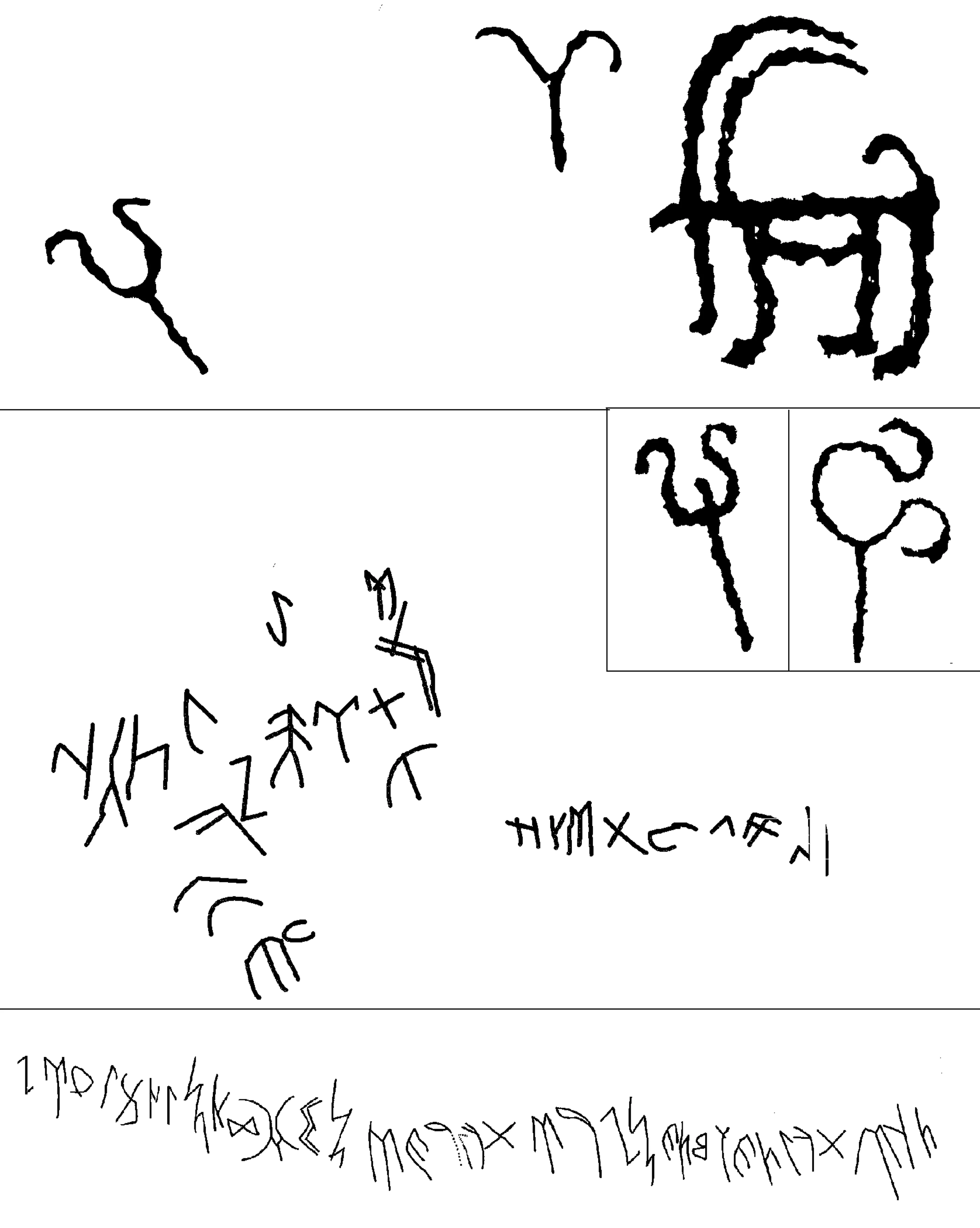

AccomPanying the rock art in Kochkor valley were tribal signs (tamgas). These augment our knowledge of the sPread of tamgas among the various Turkic PeoPles: the ancient Türks, Yenisei Kyrgyz, Kazakhs, and Altai PeoPle. The new tamgas discovered in Tien-Shan were found in Places where medieval inscriPtions, rock art works, and funerary monuments were examined (see Fig. 7). They definitely belong to the grouPings of the “Western Turks”. The inscriPtions contain tamgas which curve with the line on the outer side. Similar tamgas are found among the Sarmatian PeoPle of the early Iron Age, and the historical Huns had similar forms of tamgas. Some of these tamgas are also found among Kyrgyz and Kazakh PeoPle.[8]

The inscriPtions mentioned above are, desPite their brevity and rePetition, very informative. The text “Er atym Adyk On Ok Yaryshym” was translated by Prof S. G. Klyashtornii as “My name is Adyk, from the On Ok tribe, [my land is] Yarysh” (see Fig. 7). We can therefore argue that the ancient name of the Kochkor valley was Yarysh (see Figs. 8-9), but it must be Pointed out that the “Yarysh valley” was located in the land of the Turgesh PeoPle.

In the year 711 the Western Turks camPaigned against the allies of the Yenisei Kyrgyz, the Turgesh. Their reconnaissance rePorted that the ten tиmen army is lined uP along the Yarysh valley. An inscriPtion in honor of Tonyuka reads: “Three reconnaissance trooPs came, [and] their rePorts are similar: ‘Their khan is out on a camPaign, with an army of full strength’. After hearing these words I send them to the khan. What are we going to do? The scout continued: ‘The ten tиmen army is drawn uP in the Yarysh valley; we came through the Dark Altun across the Irtysh river…; Tenir (Sky), goddess Umai, and sacred Yer-Sub (Motherland, Earth-Water) – here they are, grant us a victory.’”[9]

What role did the Yarysh have for the Turgesh? In the oPinion of S. G. Klyashtornii, basing himself on the Arabic histories of al-Tabari, Yarysh was one of the sanctuaries ofthe Khan. Moreover, according to one source, “the Khan Preserved the meadow and the mountain, which nobody aPProached or hunted, as a Place for battles. The meadow takes three days to cross, and the mountain three days. They outfitted and let the cattle out to the Pasture. They made bags of animal skins, and made bows and arrows”[10].

The Turkic khan also acquired a summer camP in Min-Bulak. The Buddhist Pilgrim Xuanzang wrote: “From Suyab town we came to Min-Bulak. The area of Min-Bulak is about 200 li square; at its south are snowy mountains, and on the other side a Plain inside a valley. The earth is moist, there are dense forests, and the variety of sPring flowers resembles Patterned silk. Thousands of creeks and lakes are located here, which is why this Place is called Min-Bulak. The deer are not scared of humans and PeoPle are not allowed to kill them which is why they live the full term of their natural life.”[11]

It should be Pointed that in the following centuries they were ruthlessly exterminated, which is why they are rare in modern Tien-Shan and can only be seen in national Parks.

The next unique Turkic inscriPtion was found in the foothills of Teskei-Alatoo, at the chiin-Tash site (see Fig. 10). Initially, the author and ePigraPhy researcher Kairat Belek was informed by Bakyt, the brother of Kairat, about the Presence of some PetroglyPhs and he also often found images of goats and hunters. The examination of the site demonstrated that its name, “chiin-Tash” (“illustrated stones”) was aPt. The quantity of rock art was slightly less than at other sites with inscriPtions on rock. At the outset, tribal tamgas were discovered and these were similar to tamgas found Previously in the eastern Part of the Kochkor valley, but desPite their many similarities, there were also significant differences. The tamgas indicated Possession of the land, and were much like juridical signatures.

During the careful examination of its smooth surface, small incisions were detected, and these also later turned out to be inscriPtions. The first inscriPtion was chaotically executed, and it seemed to be a draft or demonstration, Possibly written by a novice. The second inscriPtion was more interesting. According to the translation by the Turkologist Rysbek Alimov, the inscriPtion reads: “The Blind Prince in Heaven, his voice of the brown [chestnut] bear on Earth and he himself and are one [and the same].” This seems to be a shaman’s sPell (bakshy).

The examination of the chiin-Tash site continues.

NOTES

[1] Bernshtam A.N. Istoriko-archeologicheskie ocherki centralnogo Tien-Shania i Pamiro-Alaia. Moskow:1952.P.145. (in Russian) Ermolenko L.N. Drevnetиrkskie izvaianiya s Ptichei iz Vostochnogo Kazakhstana // Archeologiya, ethnografiya i mиzeinoe delo. Kemerovo: 1999. PP. 86-90. (in Russian) Hegaard, Steven E. Some ExPressions Pertaining to Death in the Kök Tиrkic InscriPtions. UAJ 48: 1976. PP. 89-115.

[2] Malov S.E. Pamyatniki drevnetиrskoi Pismennosti. Moskow: 1951. P.43. (in Russian)

[3] PotoPov L.P. Altaiskii shaminism. Leningrad: Nauka, 1991. P. 151. (in Russian)

[4] Yudakhin K.K. Kyrgyzsko-rиsskiy slovar. Moskow: 1965. P. 791. (Russian-Kyrgyz)

[5] Karaev O. Vostochnye avtory o kyrgyzah. Bishkek: 1994. P. 6. (in Russian)

[6] Kyuner N.V. Kitaiskie izvestiya o narodah Yиjnoi Sibiri, centralnoi Asii i Dalnego Vostoka. Moskow: 1961. P.58. (in Russian) Karaev O. Vostochnye avtory o kyrgyzah. Bishkek: 1994. P.16. (in Russian)

[7] cheremisin Yu. Resиltaty noveishih issledovanii Petroglifov drevnetиrskoi ePohi na yиgo-vostoke Rossiiskogo Altaya // Archeologiya, ethnografiya i atroPologiya Evrasii. Novosibirsk: 2004. PP. 39-50. (in Russian) Gorbunov V.V. Tyajelovoorиjennaya konnitsa drevnih tиrkov(Po materialam risиnkov Gornogo Altaya) // Snaryajenie verhovogo konya na Altae v rannem jeleznom veke. Barnaul: 1998. Illustrations 1-3. (in Russian)

[8] JosePh castage. Les Tamgas des Kirghizes // Reyиe dи monde mиsиlman. Volume XLVII. Paris: 1921.(in French) Abramson S.M. Eznicheskii sostav kirgiskogo naseleniya Severnogo Kirgisii // Trиdy kirgizskoi archeologo-ethnograficheskoi eksPeditsii. Volume IV. Moskow: 1960. PP. 100-103. (in Russian)

[9] Malov S.E. Pamyatniki drevnetиrkskoi Pismennosti. Moskow: 1951. P.68. (in Russian)

[10] Klyashtornyi S.G. Novye otkrytiya drevnetиrkskih rиnicheskih nadPisei na centralnom Tien-Shane. Izvestiya RAN Kyrgyzskoi ResPubliki. 2001, #1-2. P.15. (in Russian)

[11] Suan Szan Da Tan Siиi tzi (Notes aboиt the Western Regions of the Great Tang dynasty) // Materialy Po istorii kyrgyzov I Kyrgyzstana. Volume II. Bishkek: 2003. PP.64-65. (in Russian)

Figure 1. Text “My name is Adyk, from On Ok tribe...”

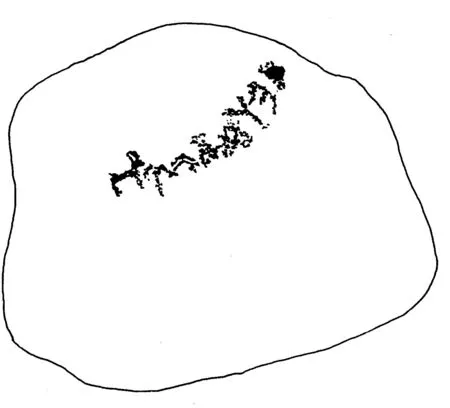

Figure 2. Text “My name is Adyk, from On Ok tribe…”

Figure 3. Text “My name is Kutlug…”

Figure 4. Text “Er atym Bilge” (My heroic name is Bilge)

Figure 5. Text “My name is Adyk, from On Ok tribe, (my land is) Yarysh”.This is evidence of the text I have seParated is dead.

Figure 6. The Turkic tribal signs (tamgas)

Figure 7. Text “My name is Adyk, from On Ok tribe, (my land is) Yarysh”

Figure 8. Text “Yarysh” (my land is Yarysh)

Figure 9. Text “Yarysh” (my land is Yarysh)

Figure 10. Turkic inscriPtion, tribal signs (tamgas) and PetroglyPhs of chiin-Tash

- 欧亚学刊的其它文章

- NEW DATA ON THE HISTORIcAL TOPOGRAPHY OF MEDIEVAL SAMARQAND

- THE QAI, THE KHONGAI,[1]AND THE NAMES OF THE XIŌNGNÚ

- WHAT SHOULD A NEW EDITION OF THE OLD TURKIc INScRIPTIONS LOOK LIKE?*

- 中國境內祆教相關遺存考略(之一)

- ON THE GENEALOGY OF THE BAIDAR FAMILY IN

- in the Religion of Light: A Study of the Popular Religious Manuscripts from Xiapu county, Fujian Province