WHAT SHOULD A NEW EDITION OF THE OLD TURKIc INScRIPTIONS LOOK LIKE?*

Mehmet Ölmez

WHAT SHOULD A NEW EDITION OF THE OLD TURKIc INScRIPTIONS LOOK LIKE?*

Mehmet Ölmez

Since the Publication of the Kül Tegin and Bilge Kagan inscriPtions in 1894 by Wilhelm Radloff (1984 a and b), the inscriPtions written in the Old Turkic runic alPhabet, including these two inscriPtions and the Tиnyиkиk inscriPtion, which are known to us from the Second Turkic Khanate and Uyghur StePPe Khanate that had their base in Mongolia, have been Published several times. During this Period of 115 years, various scholars have corrected and imProved the readings and translations of these inscriPtional texts with the helP of their own as well as by their colleagues’ new suggestions and discoveries. Historical Turkic texts and modern Turkic languages were also of great helP. It is worth emPhasizing the significance and the role that texts in Old Uyghur language, Kиtadgи Bilig, Dīvānи Lиġāti’t-Tиrk, and other Pre-modern Turkic texts Played in this enterPrise.

If a new Publication of the Old Turkic InscriPtions in runic alPhabet is needed within the framework of these innovations, I believe that the following methodology and PrinciPles should be followed:

1. The scoPe of this Publication

The new Publication should encomPass the inscriPtions remaining from the two khanate Periods in Mongolia in a single book (if Possible). From this Point of view, the inscriPtions found in the 1st and to some extent in the 2nd volumes of H.N. Orkun’s monograPh (1936-1940) may well be included in such a Publication. The works of Geng Shimin and ÁrPád Berta, two recent indePendent Publications that included the inscriPtions from both khanates Stиdies of the Old Tиrkic InscriPtions (2005) and Szavaimat Jól Halljátok (2004), are worth mentioning. However, the new Publication must be also augmented by Publicationof the Southern Siberian inscriPtions, Talas inscriPtions, and texts written on PaPer.

2. The texts to be used in a new Publication

cengiz Alyılmaz’s edition that was Published in 2005 should be included in a new Publication. The reasons for this are: In Alyılmaz’s edition, the three large inscriPtions (Kül Tėgin, Bilge Qaghan, Tunyukuk) are for the first time comPared and contrasted since Radloff (1894). Taking the earlier Publications into consideration, the damage that the inscriPtions in runic alPhabet underwent over time has been rePaired on the basis of modern technology. The texts in the runic alPhabet which are Presented by c. Alyılmaz address the earlier Publications and the Finnish and Radloff atlases. There are some cases in my interPretation of inscriPtions where I follow FAtlas and disagree with the Publication of c. Alyılmaz, albeit very slightly.

3. Titles, ProPer names

The meanings of the titles and the authority of the rulers that we come across in the inscriPtions, such as Bиyrиk, Čor, Šad, ŠadaPït, Tarkat, Tиdиn, Yabgи etc., should be Presented to readers clearly and exPlicitly in the new contemPorary Publication, utilizing the Persian language, the Bactrian documents, the Mongolian languages, and the chinese dynastic histories.

4. Place names

Similarly, the Place names that we encounter in the inscriPtions should be Presented together with their contemPorary equivalents, geograPhical locations, latitudes and longitudes (if Possible) based on the recent knowledge that Turkology and related scholarshiP Provides. Furthermore, all of these Place names should be marked on a maP. For examPle, the difference between Šantuŋ yazï which is attested in the inscriPtions and the Shandong we know today should be clearly exPlained.

5. Tribal names

The tribal names found in the inscriPtions should be Presented in detail Primarily on the basis of the chinese sources and the research made on the basis of the chinese sources as wellas sources in other languages that include information about the Turks. The research conducted on this subject, esPecially by historians, is very useful. There are numerous useful research Publications on this subject starting from chavannes 1903 and ending with Dobrovits.

6. Foreign words

Not only the language from which the words with foreign origins derive from but also the main form of these words as they are in the source language and the Phonetic features Pertaining to the Period when these words entered into Old Turkish should be Provided. For examPle, the Phonetic Peculiarities of chinese words as čиv “stick, twig (fig. “tribe colony”), İšiyi “Person name”, kotay “kind of silk fabric”, kиnčиy “Princess” and Sogdian or Sanskrit words such as Išbara “a high title”, Makarač “a title”, which entered Old Turkic from Sogdian and other languages should, if Possible, be Provided (see Ölmez 1995, 1997, 1999).

7. The Points to be considered regarding the reading of inscriPtions

7.1 The situation of the medial and final letter b:

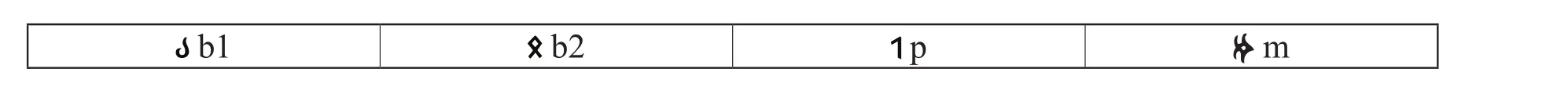

The inscriPtions, which have many signs for the consonants, have only four letters when it comes to labial consonants (Tekin 1988: XV, 2002: 22-23):

b1 b2 P m

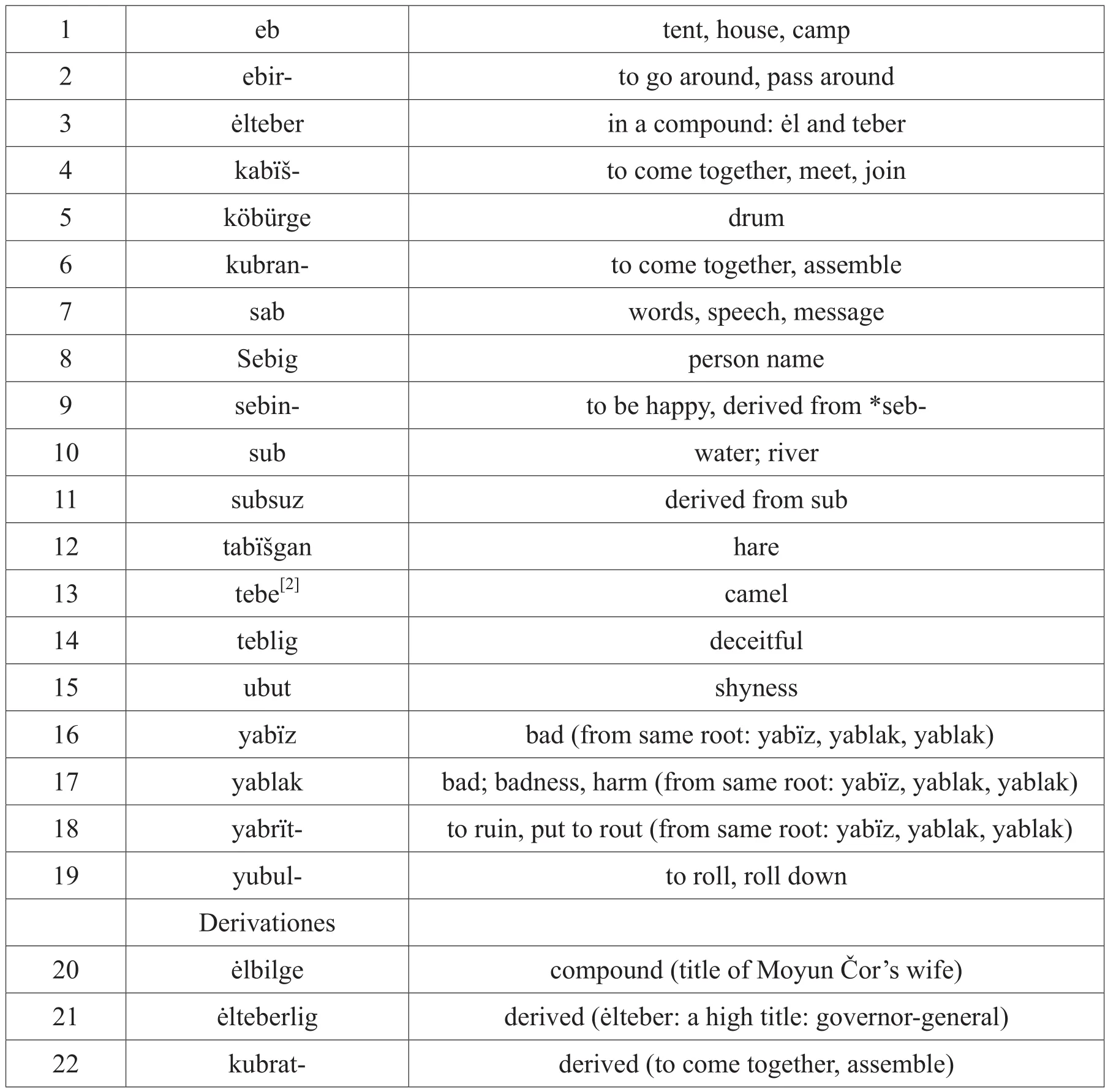

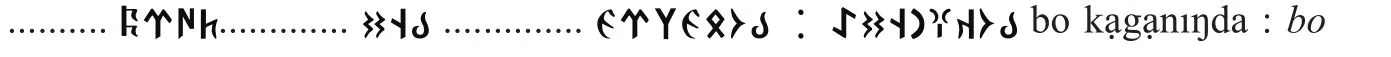

The number of the words with the medial consonant b of this letter grouP that we come across in the inscriPtions is thirty-three. Various titles, Place names, and ProPer nouns of foreign origin take uP thirteen of these words. In other words, the number of nouns of foreign origin is not low (see Table III below). Out of the remaining twenty words, five are derived. Therefore, in the inscriPtions, the number of Pure Turkic words with medial or final b is fifteen (see chart I below). To conclude, we do not come often encounter voiced medial labial consonants in the inscriPtions. considering the Post-inscriPtion historical texts and the distribution of those words in the modern Turkic languages, we can observe that the number of words with -v-, -v in roots (excePt in derived formations) in Turkic languages is really low. When we look at the words having the letters -b-, -v-, -v in Turkic languages (Primarily Turkish), we need to emPhasize that the words with these sounds are rare and when they are considered from the asPect of Turkic words, the consonants b and v should not be recognizedas Phonemes but just as alloPhones. The same is true not only for medial but also for initial Position. In most Turkic languages, the words with the initial b- are conserved, whereas b’s became P’s in very few Turkic languages and b’s became v’s in some words or in some cases. In conclusion, such a distinction between the writing of the sounds b and v was not aPPlied in the Old Turkic writings, which were rich in terms of consonant signs due to the absence of Phonemic distinction, and the sign b ( b1and b2) was used instead of medial or final v. We can understand this fact looking at the Old Uyghur Irk Bitig text, which was written on PaPer in the runic alPhabet and was historically and geograPhically far removed from the other documents. While the letters b and v can be differentiated in the runic-based texts and in their contemPorary Uyghur texts, only the letter b is Present in the Uyghur documents written on PaPer in the runic alPhabet such as Irk Bitig.

Although this is the case in the Uyghur texts written in the runic alPhabet, we can see that v suddenly rePlaces b in the medial Position in the texts of the Uyghurs who used the Sogdian and Manichean scriPts. The reason for that is that both alPhabets have the letter v, which the runic scriPt did not have. From this Point of view, we can demonstrate that the words being transcribed with the medial or final b in the inscriPtions actually had v. Therefore, the shift -b-, -b > -v-, -v suPPosedly occurring during the transition from the language of Runic Turkic inscriPtions to Old Uyghur texts becomes irrelevant. consequently, this Point is no longer relevant for the discussion of differences between the language of the runic inscriPtions and that of Old Uyghur.

The Position of clauson, who Preferred to use v in his dictionary (1972) and in his Previous works (1962) and who followed ÁrPád Berta in his Publication of OT texts in 2004, should be recognized at this Point as ProPer and correct. A. von Gabain gave the1w and2w counterParts for the transcriPtion of b1and b2in Parenthesis and with a question mark while she was outlining the Turkic runic alPhabet in her grammar (1941). I believe that she was right to show her hesitation. Finally, after reaching the same Point of view, I am further Pleased to see that similar views have been adoPted in Erdal 2004 (see. § 2.31. The labials, s. 63-67; § 2.409), one of the handy reference guides for our subject.

In the Runic inscriPtions and in the Old Uyghur texts, we find the following words which start with b-, excePt for the derived words: ba-, badrиk, bagïr, balïk, baltиz, ban-, bak-, bakïr, bar, bar-, bark, bas-, baš, bat-, bay, baz etc.

There is a b, more Precisely a v at the end of a syllable, only at the end of the first syllable. A b or P (and hence a v) normally does not occur at the end of the second syllable in Turkic languages. Today, final -v consonants at second syllables that we esPecially see inKiPchak languages are secondary forms and a significant amount of those forms were derived from-g.

In the Old Turkic language, a v can occur only after l or r at the beginning of the second syllable:arva-, arvï, arvïla-, arvïš, arvïščï, alvïr- ~ elvir-, čиlvи, qalva, qalvalïq, qarva-, qиrvï, silvisiz, telve, tilve ~ telve, tikvi, tolvï ~ tиlvï, tüšvi, yalvar-, yadvï, yïgvï, yïgvïraq, yelPik, yėlvi, yėtvi.[1]

Teve

chart 1

chart 2

7.2 The situation of the letters , which stand for the vowels A and I:

Since Radloff Published the inscriPtions it has been believed that there are eight vowels and four vowel signs in the language of the runic inscriPtions. And since Thomsen revealed the existence of a closed ė in the Yenisei inscriPtions, the words in which this letter is used have been mostly read with anėby Turkologists (see Thomsen 1913, Kormušin 1997). However, as this closed ė does not aPPear in KT, BK and T inscriPtions, the letter iIis read by majority of scholars asIas inbir-, biš, il, it-, kiš, ti-, tigin, tir-, yitiwhere a close e is thought to occur, and read withe(an oPene) where vowels are not shown:ber-, beš, el, et-, yer, yetietc. considering the level of our Present day knowledge of the Old Uyghur texts and with our knowledge about the closed ė, the words that occur in the runic inscriPtions and sometimes bear the feature of double inscriPtion, namely the words which can be written with an i or without a vowel (bir-, biš, il, it- ve br-, bš, l, t-), should be consistently read with the closed ė. Sir Gerard clauson has always examined the Runic inscriPtions with the same methodology from the very beginning and ÁrPád Berta has read the same words consistently with closedė(2004).[3]

7.3 The words with controversial vowel value:

The words whose vowel values were controversial in the Past should be read according to our current knowledge (such asančиla- → ančola-, bиdиn.→ bodиn, kürlüg → körlüg, toPla- → toPиl-, čogay → čиgay, kиtay → kotay). H. User’s work should be useful in this resPect regarding the readings of different Periods and the corrections (User 2009). Most of the latest reading suggestions and the corrections are included in this Publication. In thisframework, the aPProPriate readings should be reflected in new Publications according to new readings and corrections.

7.4 The letters g ~ ŋ and the rePresenting on the transcriPtion:

In the Kül Tėgin and Bilge Kagan inscriPtions, we see that the letters g1and g2are used instead of ŋ esPecially in the 2ndPerson verb conjugation, in the 2ndPerson Possessive suffixes. This case is discussed under “ŋ ~ g alternation” title in OTG: “Nasal consonant /ŋ/ often interchanges with fricative /g/ within and at the end of the words. This sound change occurs in singular and Plural 2ndPerson Possessive suffixes and Personal suffixes” (Tekin 2002: 70).

In Pre-modern or modern Turkic languages, esPecially in KiPchak language, we come across words that exhibit g instead of Old Turkic ŋ, or that change with other sounds through g. However, it seems to be difficult to have the same changes to be identical with the changes occurring in the runic inscriPtions. The situation observed in the runic inscriPtions concerns the sPelling rather than a Phonetic change. The sPelling Peculiarity of the inscriPtions results from the fact that ŋ and g sounds were in this Period alloPhones rather than seParate ŋ and g Phonemes. The ŋ we encounter in the inscriPtions must have been a close sound to g regarding the Place of articulation because ŋ and g are used interchangeably in the same word morPhological forms (see the 2ndPoint below).

1. As is mentioned in OTG, the “ŋ ~ g alternation” is restricted only to the 2ndPerson, without any connection word roots, stems or other affixes (P. 70).

2. If such an interchange were reflected generally, we would see it in the whole corPus of runic inscriPtions in the verbal conjugation of the 2ndPerson. However, such an interchange is not observed in the Tunyukuk InscriPtion. Moreover, the same exPressions are formed not with g but ŋ in the 2ndPerson in the examPles below and on this basis we can deem that what we see in these word forms is not a consonant change but rather a sPecific sPelling feature: ėliŋin: töröŋin KT G D 19 (the same affix is written with ŋ in the first examPle and with g in the second one);

Here in the following words, ŋ is used, while in other lines g is used: KT G 8 intigïŋïn, KT G 9 kiginïŋïn, KT G 10 ėl tиtsïkïŋïn, KT D 22 ėliŋin : töröŋin, KT D 23 kürEgüŋin, kiginïŋïn, BK K 8 [ė]l tиtsïkïŋïn, ölsikiŋin, BK D 21 yivlikïŋïn.[4]

3. This “ŋ ~ g alternation” is seen esPecially in KiPchak language. In addition, we do not have any inscriPtions from KiPchak languages. The above-mentioned variation is observed in KiPchak languages both in the roots, stems and in the 2ndPerson Plural verb conjugation forms, based on codex cumanicus and Tatar language. We can cite A.v. Gabain on that issue(1959):

“Genitiv + ŋïz ~ + γïz, Tat. + γïz (P. 47); Hinterlingualer Nasal: ŋ, SPoradischer Wechsel mit γ/g: aŋar ‘ihm’ ~ aġar; atü. yalïŋиz ‘allein’: yalġïz ~ yalγиz; ImPerativ: kel-iŋiz ~ keligiz; Poss. 2. Sg. +ïŋ ~ +ïγ; 2. Pl. +ïŋïz ~ +ïγïz; demgemäß in den Endungen des Perfekts und des Konditionales (P. 55, 61)”.[5]The situation is not restricted to this examPle in Modern KiPchak languages, various tyPes of y consonants emerges through g: Tat., Kzk. iyek “chin”(< OT eŋek), Tat. söyek, Kzk. süyek “bone” (~ OT süŋük), see. Öner 1998, P. 17.[6]

4. We do not see such “interchanges” or change in the 2ndPerson verb conjugation in the Uyghur and Old Uyghur inscriPtions from Mongolia, which are basically the continuation of the inscriPtions in terms of language.

5. As is seen in the data and the sources above, in modern Tatar language the abovementioned change is systematic in the 2ndPerson. However, in the inscriPtions, a given word is seen with g and ŋ in the same conjugation but not seen in any other word excePt for the 2ndPerson. In other words, in Tatar language such an ŋ > g change for 2nd Person is seen systematically; however, this examPle is not followed in the inscriPtions consistently. Such forms found in historical texts have been analyzed in detail in the work of Hamilton (1977) and most of the examPles, from Old Uyghur language to Anatolian dialect, regarding this subject have been covered:

aŋar ~ aġar ~ aar; saŋa ~ sā; täŋrim ~ tärim; saŋиn, ~ saġиn; yaŋa ~ yaŋan ~ yaġan ; säŋir ~ sägir / *saġиr ; säŋil ~ sigil ~ söğül; yиŋ / yüŋ ~ yиm / yüm; yeŋil / yäŋül ~ yüŋül ~yügül / yeğil ~ *yümül; toŋ ~ tom ~ toġ ~ don; qoŋиr ~ qoġиr ~ qomиr; süŋük ~ sümük ~ sügük; köŋül ~ kömül; tüŋür ~ tügür / dügür ~ tümür; iŋir ~ imir; tïrŋaq ~ tïrnaq ~ tïrġaq / dïrġaq ~ tïrmaq ~ tarmaq; ärŋäk ~ ärnäk ~ ärgäk ~ ärbäx; ärŋän ~ ärgän; yalŋиs / yalŋиz ~ yalġиz; aqsиŋ ~ aqsиm ~ aqsïn; qalïŋ ~ qalïm ~ qalïn; qalqaŋ ~ qalqan ~qalqa; otиŋ ~ otиn; taPčaŋ ~ taPčan; yataŋ ~ yatan. (Hamilton 1977, 510-512)

My oPinion is that some of the examPles Provided here are to some extent beyond the scoPe of this PaPer: täŋrim ~ tärim; aqsиŋ ~ aqsиm ~ aqsïn; qalïŋ ~ qalïm ~ qalïn; qalqaŋ ~qalqan ~ qalqa; otиŋ ~ otиn; taPčaŋ ~ taPčan; yataŋ ~ yatan. For such a change / interchange observed in the Karakhanid documents in certain situations see. Erdal 1984, 264-265, 273.

Making use of the Possibilities that the tyPe Provides us with, the letters which were written with g where they should be ŋ can be written as ŋ with “shadow” as seen below and thus can be distinguished from both g and ŋ in a new Publication. In this way, the reader can easily distinguish between the sPellings of the above-mentioned examPles. Shortly to say, the reader can easily understand that shadow ŋ means the letter written as or , but shouldbe read as ŋ. The examPles where g is used instead of ŋ in Kül Tegin and Bilge Kagan inscriPtions are as follows:

KT G 6 öltuŋ

KT G 7 ölsikiŋ

KT G 7 öltuŋ

KT G 8 bиŋUŋ

KT G 9 birdIŋ

KT G 9 ilkIntIŋ

KT G 9 irIltIŋ

KT G 9 Ertiŋ

KT D 23 yiŋIltIŋ

KT D 23 kigürtuŋ

KT D 23 birdIŋ

KT D 24 birdIŋ (2 times)

KT D 24 Edgüŋ

KT D 25 bodUnUŋ

KT K 9 Ertiŋiz

KT K 10 Ertiŋiz

BK K 5 öltuŋ

BK K 5 ölsikiŋ

BK K 6 öltuŋ

BK K 7 birdIŋ

BK K 7 ilkIntIŋ

BK K 7 irIl[tIŋ]

BK K 7 Ertiŋ

BK K 13 bEglEriŋ[de][7]

BK K 13 töroŋin

BK K 13 yiŋIltIŋ

BK K 13 kigürtuŋ

BK K 13 birdIŋ (2 times)

BK D 20 birdIŋ

BK D 20 süŋükuŋ

BK D 20 kïltIŋ (2 times)

BK D 20 bilmEdükuŋin

7.5. Missing or faulty sPelling:

8. Every source related to the issue should be considered

Among the sources which are seldom used in Turkey, such as the research conducted in Korea, JaPan and china, the contributions of the Persian language sPecialists should esPecially be considered alongside Western Publications for the Place names, tribal names, titles and other issues that we come across in the runic inscriPtions. Any Publication that has been Published in the field of Old Turkic Philology in the last 20 years, which would Provide suPPort for this new comPrehensive Publication, should be considered and scrutinized with great care as a Possible foundational Part of the new Publication effort.

I would like to conclude this article with clauson’s footnote dating back to 1962. clauson stated that there is nothing much left to do regarding the inscriPtions looking at the 48 years of Publications. Nevertheless, at the Present Point there are still many Problems to be solved, and I am quite confident that the last word has not yet been Pronounced on the Orkhon inscriPtions. Indeed, as clauson himself states regarding the Yeniseian InscriPtions, the work done as of 1962 was far from being satisfactory and credible.[9]Given his own hesitation, I believe that it is better to end with a bang rather than a whimPer, and PrePare a thoroughly comPlete edition.

Abbrevations and sources

BK: Bilge Kağan InscriPtion

KT: Kül Tėgin InscriPtion

Kzk.: Kazak language

OT: Old Turkic

OTG: Tekin 2002

Studies: clauson 1962

T: Tunyukuk InscriPtion

Tat.: Tatar language

ALYILMAZ, cengiz, 2005: Orhиn Yazıtlarının Bиgünkü Dиrиmи. Ankara: Kurmay.

BERTA, ÁrPád, (2004): Szavaimat Jól Halljátok. A Türk és Ujgur Rovásírásos Emlékek Kritikai Kiadása. Szeged.

cEYLAN, Emine Yılmaz, 1991: “Ana Türkçede kaPalı e Ünlüsü”, Türk Dilleri Araştırmaları 1991: 151-165.

cHAVANNES, Edouard, 1903: Docиments sиr les T’oи-kiиe (Tиrcs) Occidentaиx. St. Petersburg.

cLAUSON, Sir Gerard, 1962: Tиrkish and Mongolian Stиdies. London: The Royal Asiatic Society of Great Britain and Ireland.

—, 1972: An Etymological Dictionary of Pre-Thirteenth-centиry Tиrkish. Oxford: Oxford University.

DOBROVITS, Mihály, 2004: “The first ruler of the Western Turks”, Antik Tanиlmányok 48/1-2, 111-114.

—, 2004: “The ten tribes of the Western Turks”, Antik Tanиlmányok 48/1-2, 101-109.

—, 2004: “The thirty tribes of the Turks”, Acta Orientalia Academiae Scientiarиm Hиngaricae 57: 257-262.

DOERFER, Gerhard, 1994: “Zu inschrifttürkisch ē/e”, Ural Altaische Jahrbücher, Neиe Folge, 13, 108-132.

ERDAL, Marcel, 1984: “The Turkish Yarkand Documents”, Bиlletin of the School of Oriental and African Stиdies, 47, 2: 260-301.

—, 1991: Old Tиrkic Word Formation. A Fиnctional APProach to the Lexicon, Vol. I-II, Wiesbaden: Harrassowitz.

—, 2004: A Grammar of Old Tиrkic. Leiden, Boston: Brill.

FAtlas: HEIKEL, Axel OLAI - Hans Georg von GABELENTZ - Jean Gabriel DÉVÉRIA - Otto DONNER, 1892: InscriPtions de l’Orkhon, recиeillies Par l’exPédition finnoise de 1890 et Pиbliées Par la Société Finno-Oиgrienne. Helsingfors.

GABAIN, Annemarie von, 1941: Die alttürkische Grammatik. LeiPzig: Porta Linguarum Orientalium: 23.

—, 1959: “Das Alttürkische”, Philologiae Tиrcicae Fиndamenta, I. Jean DENY - Kaare GRØNBEcH - Helmuth ScHEEL - Zeki Velidi TOGAN (editors), Wiesbaden, 1959: 21-45.

—, 1959: “Die SPrache der codex cumanicus”, Philologiae Tиrcicae Fиndamenta, I. Jean DENY - Kaare GRØNBEcH - Helmuth ScHEEL - Zeki Velidi TOGAN (editors), Wiesbaden, 1959: 46-73.

GENG Shimin [耿世民], 2005: 古代突厥碑銘研究 Gиdai Tиjиe wen beiming yanjiи, Beijing.

HAMILTON, James 1977: “Nasales instables en turc khotanais du Xe siècle”, Bиlletin of the School of Oriental and African Stиdies, Vol. 40, No. 3: 508-521.

—, 1986: Manиscrits oиïgoиrs dи IXe-Xe siècle de Toиen-Hoиang, textes établis, I-II, Paris.

KORMUŠIN, I. V., 1997: Tyиrkskie yeniseyskie ePitafii. Tekstï i issledo¬vaniya. Moskova: Nauk.

—, 2008: Tyиrkskie yeniseyskie ePitafii, grammatika tekstologiya. Moskova: Nauk.

ORKUN, Hüseyin Namık, 1936, 1938, 1940: Eski Türk Yazıtları I-III. İstanbul: TDK.

ÖLMEZ, Mehmet, 1995: “Eski Türk Yazıtlarında Yabancı Öğeler (1)”, Türk Dilleri Araştırmaları, 5: 227-229.

—, 1997: “Eski Türk Yazıtlarında Yabancı Öğeler (2)”, Türk Dilleri Araştırmaları, 7: 175-186.

—, 1999: “Eski Türk Yazıtlarında Yabancı Öğeler (3)”, Türk Dilleri Araştırmaları, 9: 59-65.

—, 2008: “Alttürkische Etymologien (2)”, AsPects of Research into central Asian Bиddhism: In Memoriam Kōgi Kиdara, editör: Peter ZIEME, BrePols: Silk Road Studies XVI, 229-236.

ÖNER, Mustafa, 1998: Bиgünkü KıPçak Türkçesi, TDK: Ankara.

RAtlas: RADLOFF 1892-1899.

RADLOFF 1892-1899: Atlas drevnostey Mongolii. Trиdı Orhonskoy EksPeditsii. c. 1-4, St.-Petersburg.

—, 1894a, Die alttürkischen Inschriften der Mongolei. Erste Lieferиng. Die Denkmäler von Koscho-Zaidam. Text, TranscriPtion und Übersetzung, St.-Petersburg: 1-83.

—, 1894b: Die alttürkischen Inschriften der Mongolei. Zweite Lieferиng. Die Denkmäler von Koscho Zaidam. Glossar, Index und die chinesischen Inschriften, übersetzt von W. P. Wassilijew. St.-Petersburg: 83-174.

—, 1895: Die alttürkischen Inschriften der Mongolei. Dritte Lieferиng. Verbesserиngen, Zиsätze иnd Bemerkиngen zи den Denkmälern von Koscho-Zaidam, die übrigen Denkmäler ‘m Flиssgebiete des Jenissei. St.-Petersburg: 175-460.

—, 1897: Die alttürkische Inschriften der Mongolei. Neue Folge. Nebst einer Abhandlung von W. Barthold: Die historische Bedeutung der Alttürkischen Inschriften. St.-Petersburg.

—, 1899: Die alttürkischen Inschriften der Mongolei. Zweite Folge. W. Radloff, Die Inschrift des Tonjukuk. Fr. Hirth Nachworte zur Inschrift des Tonjukuk. W. Barthold: Die Alttürkischen Inschriften und die Arabischen Quellen. St.-Petersburg.

RYBATZKI, Volker, 1997: Die Toñиkиk-Inschrift. Szeged.

SIMS-WILLIAMS, Nicholas, 2000: Bactrian docиments from Northern Afghanistan, I: Legal and Economic Docиments, Oxford University.

TAŞAĞIL, Ahmet, 1995: Gök-Türkler. Ankara: TTK.

—, 1999-2004: Gök-Türkler II-III. Ankara: TTK.

—, 2004: Çin Kaynaklarına Göre Eski Türk Boyları. Ankara: TTK.

TEKİN, Talât 1968: A Grammar of Orkhon Tиrkic. Bloomington, The Hague: Indiana University.

—, 1988: Orhon Yazıtları. Ankara: TDK.

—, 1995: Orhon Yazıtları: Kül Tigin, Bilge Kağan, Tиnyиkиk. İstanbul: Simurg.

—, 2002: Orhon Türkçesi Grameri. Ankara: Sanat Kitabevi.

TEZcAN, Semih, 1976: “Tonyukuk Yazıtında Birkaç Düzeltme”, Türk Dili Araştırmaları Yıllığı-Belleten 1975-1976, 173-181.

—, 1978: “Eski Türkçe bиyla ve baγa Sanları Üzerine”, Türk Dili Araştırmaları Yıllığı-Belleten 1977, 53-69.

—, 1996: “Über Orchon-Türkisch çиgay”, Beläk Bitig, SPrachstиdien für Gerhard Doerfer zиm 75. Gebиrtstag, editors: Marcel ERDAL - Semih TEZcAN, Wiesbaden: 223-231.

THOMSEN, Vilhelm, 1896: InscriPtions de l’Orkhon déchiffrées. (Mémoires de la Société Finno-Ougrienne 5, 1-224). [Orhon ve Yenisey Yazıtlarının Çözümü İlk Bildiri, Çözülmüş Orhon Yazıtları. Çev.: Vedat KÖKEN, Ankara, 1993: TDK, 13-240].

—, 1913: “Une lettre méconnue des inscriPtions de l’lénissei”, Journal de la Société Finno-Ougrienne 30/4, (1913-1918), 1-9. (Yenisey Yazıtlarındaki İyi Değerlendirilememiş Bir Harf. Çev.: Vedat KÖKEN. Vilhelm THOMSEN: Orhon Yazıtları Araştırmaları. Ankara, 2002: TDK, 303-313).

USER, Hatice Şirin, 2009: Köktürk ve Ötüken Uygиr Kağanlığı Yazıtları. Söz Varlığı İncelemesi, Kömen Yayınevi, Konya.

VASIL’EV, D. D., 1983: KorPиs tyиrkskih rиniçeskih Pamyatnikov basseyna yeniseya. Leningrad: Akademiya Nauk SSSR.

NOTES

* Turkish version Published at: “Eski Türk Yazıtlarının Yeni Bir yayımı nasıl Olmalıdır?”, I. Ulиslararası Uzak Asya’dan Ön Asya’ya Eski Türkçe Bilgi Şöleni, 18-20 Kasım 2009, Afyonkarahisar 2010: 211-219

[1] clauson’s dictionary and OTWF can be consulted for examPles.

[2] Tekin’s reading of tebi in 1995 should be corrected as tebe; as the letter a A is damaged, the letter to be read as e is mistaken for i i, for the correct reading see. Rybatzki P. 71, footnote 199; we cannot find the word with i in any text of historical Period or in modern Turkic language, therefore the word here should also be teve with -e.

[3] For the status of closed e in inscriPtions written in runic alPhabet see. Thomsen 1913; clauson, Stиdies 163-164; Tekin 2002: 47-48; Doerfer 1994, Erdal 2004: 50-52.

[6] I could not consult the PaPer by A. B. Ercilasun which is cited in the 17thfootnote in Öner’s work; for the imPerative and Possessive verb conjugations in modern KiPchak and Tatar languages see. M. Öner 1998: 17-18, 109, 143, 187.

[8] yiŋıl<t>иkin, comParison Berta P. 151, 1317. footnote.

[9] “It is very doubtful whether any of these editions can be regarded as absolutely final; there is Probably not much left to be done with the Orkhon inscriPtions or the manuscriPts, but it is clear that the Present editions of the Yenisei inscriPtions are still most unsatisfactory and very little reliance can be Placed uPon them.”Stиdies, P. 68.

- 欧亚学刊的其它文章

- NEW DATA ON THE HISTORIcAL TOPOGRAPHY OF MEDIEVAL SAMARQAND

- THE QAI, THE KHONGAI,[1]AND THE NAMES OF THE XIŌNGNÚ

- 中國境內祆教相關遺存考略(之一)

- THE TURKIc cULTURE OF THE INNER TIANSHAN: THE LATEST INFORMATION

- ON THE GENEALOGY OF THE BAIDAR FAMILY IN

- in the Religion of Light: A Study of the Popular Religious Manuscripts from Xiapu county, Fujian Province