Risk factors for medical complications of acute hemorrhagic stroke

Jangala Mohan Sidhartha, Aravinda Reddy Purma, Lomati Venkata Pavan Kumar Reddy, Nagaswaram Krupa Sagar, Marri Prabhu Teja, Meda Venkata subbaiah, Muniswami PurushothamanRajiv Gandhi Institute of Medical Sciences, Kadapa 5600, IndiaDepartment of Clinical Pharmacy, P. Rami Reddy Memorial College of Pharmacy, Kadapa 5600, IndiaP. Rami Reddy Memorial College of Pharmacy, Kadapa 5600, India

Risk factors for medical complications of acute hemorrhagic stroke

Jangala Mohan Sidhartha1, Aravinda Reddy Purma1, Lomati Venkata Pavan Kumar Reddy2*, Nagaswaram Krupa Sagar2, Marri Prabhu Teja2, Meda Venkata subbaiah3, Muniswami Purushothaman3

1Rajiv Gandhi Institute of Medical Sciences, Kadapa 516003, India

2Department of Clinical Pharmacy, P. Rami Reddy Memorial College of Pharmacy, Kadapa 516003, India

3P. Rami Reddy Memorial College of Pharmacy, Kadapa 516003, India

ARTICLE INFO ABSTRACT

Article history:

Received 29 Mar 2015

Received in revised form 3 Apr 2015 Accepted 19 Apr 2015

Available online 3 Aug 2015

Keywords:

Hemorrhagic Stroke Hypertension

Risk factors

Mortality

Diabetes mellitus

Stroke complications

Objective: To assess the risk factors leading to medical complications of hemorrhagic stroke. Methods: We conducted an observational study in neurology, emergency and general medicine wards at a tertiary care teaching hospital in Kadapa. We recruited hemorrhagic stroke patients, and excluded the patients have evidence of trauma or brain tumor as the cause of hemorrhage. We observed the subjects throughout their hospital stay to assess the risk factors and complications.

Results: During period of 12 months, 288 subjects included in the study, 89% of them identified at least 1 prespecified risk factor for their admission in hospital and 75% of them experienced at least 1 prespecified complication during their stay in hospital. Around 47% of subjects deceased, among which 64% were females.

Conclusions: Our study has assessed that hypertension followed by diabetes mellitus are the major risk factors for medical complications of hemorrhagic stroke. Female mortality rate was more when compared to males.

Tel: +91-9032805464

E-mail: pavankumar.lomati@gmail.com

1. Introduction

Stroke is traditionally defined as a clinical syndrome characterized by an acute loss of focal brain function with symptoms lasting more than 24 h or leading to (earlier) death, and it is due to inadequate blood supply to a part of the brain (ischemic stroke) or spontaneous hemorrhage into a part of the brain (primary intracerebral hemorrhage) or over the surface of the brain (subarachnoid hemorrhage)[1]. Haemorrhagic stroke (HS) is caused by bleeding of a blood vessel supplying the brain. Subarachnoid hemorrhage, which usually occurs due to rupturing of an aneurysm, may also lead to stroke. It tends to more severe and associated with higher early mortality[2]. HS most commonly occur in association with hypertension. Several factors identified as associated with an increased risk of stroke; see Table 1[3].

Table 1Risk factors for stroke.

The hospital mortality and morbidity rate of patients with acute stroke ranges from 7.6% to 30%. From these, neurological deaths constitute about 80% and non-neurological deaths constitute about 17%[4]. Neurological deaths such as progressive increased intracranial pressure and subsequent herniation were the most common causes of death in both groups within the first 4 days of admission[5].

Medical complications after stroke are common, present barriers to optimal recovery or related to poor outcomes and are potentially preventable or treatable[6]. Estimates of frequency of complications range from 40% to 96% of patients, with severity of stroke as the most important risk factor[7]. The complications have been fatal in some cases, contributing to the hospital mortality[8].

2. Materials and methods

The departments included General medicine, Emergency medicine and Neurology. Patients required from each department had at least 18 years of age or older and clinical diagnoses of hemorrhagic stroke with a measurable neurological deficit occurring within 7 days and reviewed their progress on a weekly basis until discharge from the hospital. Eligible patients had seen and consecutively approached for enrollment, with a target enrollment of 20 patients from all departments. We excluded patients with trauma, brain tumor as the cause of hemorrhage and patient with incomplete followups. Evidence or clinical suspicions of ischemic stroke patients were also excluded. Each participating site obtained institutional review board approval before the study initiation, and each patient provided written informed consent prior the enrollment. Duration of study participation for each patient was a single site visit. Enrolled patients had clinical and laboratory information abstracted from their medical records by office staff. We utilized a data collection form to assess risk factors and monitor the incidence of complications. Information abstracted from the chart included: sex, age, race, date of recruitment, diabetes, hypertension, hypercholesterolemia, elevated triglyceride levels, low density lipoprotein, current smoker and significant alcohol intake. Glasgow Coma Scale and modified Rankin scale were also recorded.

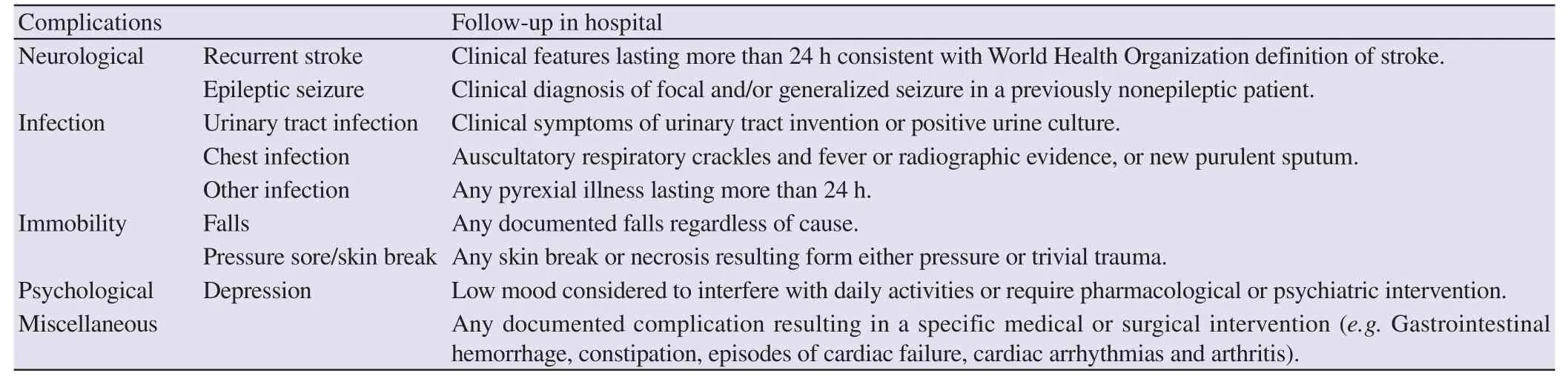

Table 2Modified predefined complications.

Following the work by Langhorne et al, modified predefined complications were utilized to monitor the occurrence of complications (Table 2)[3]. These complications monitored on daily by the physician. The selected potentially life threatening complications are as follows: acute congestive aspiration pneumonia, cardiac arrhythmias, chest infections, deep vein thrombosis, epileptic seizure, falls, heart failure, pulmonary embolism and recurrent stroke. The patient’s condition, whether he survived or succumbed to his illness, was noted upon discharge.

3. Results

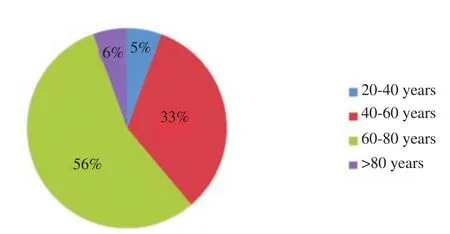

Two hundred and eighty eight consecutive patients recruited from all departments. There were 152 (52.8%) males. Mean age was (71.0 ± 9.2) years and 218 (75.7%) had their first-ever stroke. Most of these patients were in the age group of 60-80 years (Figure 1). One hundred and twenty three (42.7%) patients admitted to a general neurology, 89 (31%) to an emergency ward and 76 (26.4%) to a general medical ward.

Figure 1. Patient distribution based on age group.

3.1. Risk factors for admission

On admission, the following risk factors were noted among the subjects: hypertension in 217 (75.35%), diabetes mellitus in 76 (26.39%), alcohol consumption > 30 g/day in 88 (30.56%) and current cigarette smoking in 92 (31.94%). One hundred and eighty nine (65.6%) had a Glasgow Coma Scale score≥8. A total of 257 patients (89.23%) experienced at least 1 prespecified risk factor for their admission in hospital. The main risk factors showed in Table 3.

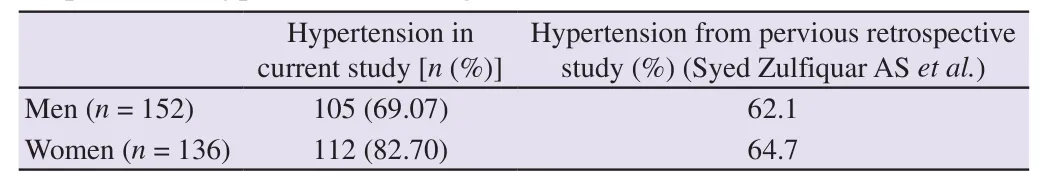

Among these hypertension is a major risk factor for causing stroke, the proportion of hypertension in HS patients showed in Table 4 (along with summary results from previous retrospective of HS patients).

Table 3Risk factors in HS patients.

Table 4Proportion of hypertension among HS.

3.2. Complications in hospital

A total of 216 (75%) complications were seen in this cohort of patients. Among the neurological complications, 36 (12.50%) patients developed recurrent stroke and 24 (8.33%) had epileptic seizure. Among the non-neurologic complications, the most commonly encountered were diabetes, constipation, and chest infections with a rate of 11%, 7.63%, and 6.25% respectively.

Recurrent stroke and seizure were more frequent during the first week. Chest infection was the most common complication during the entire two weeks of observation, with a peak incidence during the first week. The main complications of our study showed in Table 5.

Table 5Complications after admission in hospital.

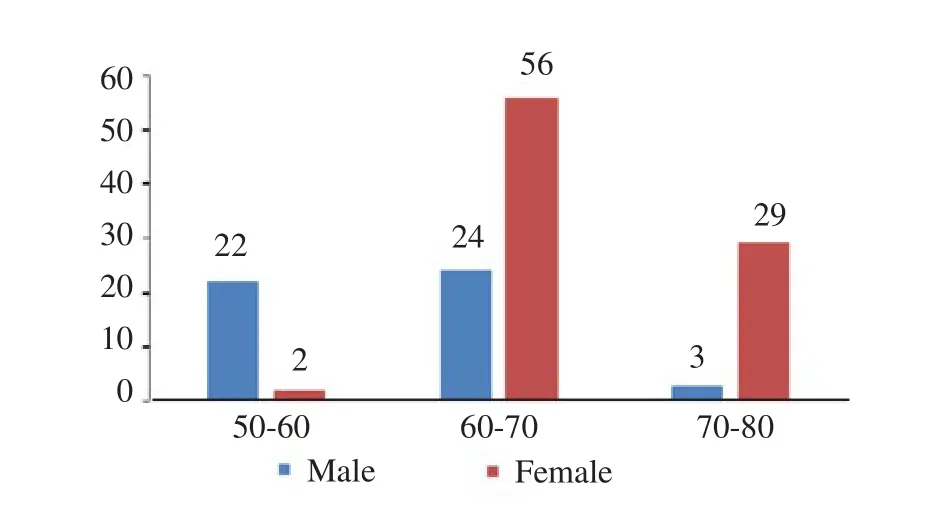

3.3. Mortality

One hundred and fifty two (52.78%) were discharged alive and 136 (47.2%) died during confinement. Most of these deaths occurred during the first week from admission. Among 87 (64%) were females in the age group of 50-80 years shown in Figure 2.

Figure 2. Distribution of HS mortality.

4. Discussion

This study conducted among the patients attending in RIMS, Kadapa to ascertain the risk factors for causing complications of HS in adults. Out of 288 patients male ratio was slightly increased when compared to women, similarly in a cohort study showed 57% male ratio[4]. Most people fall in the age group of 60-80 years.

4.1. Risk factors

Hypertension is a major risk factor common to both coronary heart disease and stroke, in our study the rate was 75.34%. There is prolific evidence, both from cohort studies and case–control studies, shows that hypertension is the single most important risk factor for intracerebral hemorrhage[9,10]. Out of 217 hypertension patient shows 203 patients were having blood pressure > 160/90 shows almost 7 fold increased risk for HS when compared to normotensives. Similarly a meta-analysis showed that self-reported hypertension or a measured blood pressure of > 160/90 increased the risk of ICH more than nine fold[9]. The proportion of hypertension in our study was more in women but in a study the rate was very similar in men[11].

Diabetes mellitus, smoking and alcohol were showing similar risk for HS. Smoking studies have consistently shown tobacco use as a risk factor for ICH, though the effect size is not as large as for hypertension[12,13]. There is compelling evidence relating high alcohol intake with a higher risk of ICH[10,12].

4.2. Complications

In our study the complications after occurrence of stroke was 75%, similarly earlier studies have demonstrated that complications after the occurrence of stroke showed range from 40% to 96%[5,8]. Among these death (47.2%), loss of muscle control (38.9%) and speech problem (35.7%) were the major complications followingoccurrence of stroke. Our findings that approximately 8.33% of patients were shows seizures after admission in hospital, similarly some studies reported range from 1.4% to 17%[14]. Hypertension and diabetes mellitus were the major comorbid conditions in our study.

4.3. Mortality

Patients with HS are generally at high risk for mortality[15,16]. In our study the mortality rate was 47.2%. The mortality rate was high in our study, when compared to other studies the ranges from 7.6% to 30%[17]. Hematoma expansions, edema formation, and intraventricular hemorrhage leading to increased intracranial pressure are likely contributors to the acute excess mortality[18-20].

In adults hypertension followed by diabetes mellitus are the major risk factors for medical complications of HS. Female mortality rate was more in hemorrhagic stroke compared to men. Females are more prone to hemorrhagic stroke because of high risk of hypertension.

Conflict of interest statement

The authors report no conflict of interest.

Acknowledgements

The authors are grateful to staffs of Rajiv Gandhi Institute of Medical Sciences for their contribution and help.

References

[1] Gorelick PB, Testai F, Hankey G, Wardlaw JM. Hankey’s clinical neurology. 2nd ed. Boca Raton: CRC Press; 2014.

[2] Ganti L, Jain A, Yerragondu N, Jain M, Bellolio MF, Gilmore RM, et al. Female gender remains an independent risk factor for poor outcome after acute nontraumatic intracerebral hemorrhage. Neurol Res Int 2013; doi: 10.1155/2013/219097.

[3] Mant J, Walker MF, editors. ABC of stroke. Hoboken: John Wiley & Sons, Ltd. Publication; 2011, p. 1-25.

[4] Navarro JC, Bitanga E, Suwanwela N, Chang HM, Ryu SJ, Huang YN, et al. Complication of acute stroke: a study in ten Asian countries. Neurol Asia 2008; 13: 33-9.

[5] Indredavik B, Rohweder G, Naalsund E, Lydersen S. Medical complications in a comprehensive stroke unit and an early supported discharge service. Stroke 2008; 39: 414-20.

[6] Ji R, Wang D, Shen H, Pan Y, Liu G, Wang P, et al. Interrelationship among common medical complications after acute stroke pneumonia plays an important role. Stroke 2013; 44: 3436-44.

[7] Rocco A, Pasquini M, Cecconi E, Sirimarco G, Ricciardi MC, Vicenzini E, et al. Monitoring after the acute stage of stroke: a prospective study. Stroke 2007; 38: 1225-8.

[8] Ingeman A, Andersen G, Hundborg HH, Svendsen ML, Johnsen SP. Processes of care and medical complications in patients with stroke. Stroke 2011; 42: 167-72.

[9] O’Donnell MJ, Xavier D, Liu L, Zhang H, Chin SL, Rao-Melacini P, et al. Risk factors for ischaemic and intracerebralhaemorrhagic stroke in 22 countries (the Inter-Stroke study): a case–control study. Lancet 2010; 376(9735): 112-23.

[10] Zhang YD, Bayoumy IE, Zhang YH, Yang HJ, Liu J. Risk factors and predictors of early mortality after acute stroke: hospital based study. Glo Adv Res J Med Med Sci 2014; 3(6): 111-6.

[11] Shahab F, Irfan MS, Shuaib A, Syed ZAS. Hemorrhagic stroke; frequency of hypertension, diabetes and smoking in patients. Prof Med J 2014; 21(6): 1204-8.

[12] Zhang Y, Tuomilehto J, Jousilahti P, Wang Y, Antikainen R, Hu G. Lifestyle factors on the risks of ischemic and hemorrhagic stroke. Arch Intern Med 2011; 171(20): 1811-8.

[13] Andersen KK, Olsen TS, Dehlendorff C, Kammersgaard LP. Hemorrhagic and ischemic strokes compared: stroke severity, mortality, and risk factors. Stroke 2009; 40(6): 2068-72.

[14] Yang TM, Lin WC, Chang WN, Ho JT, Wang HC, Tsai NW, et al. Predictors and outcome of seizures after spontaneous intracerebral hemorrhage. Clinical article. J Neurosurg 2009; 111: 87-93.

[15] Connolly ES Jr, Rabinstein AA, Carhuapoma JR, Derdeyn CP, Dion J, Higashida RT, et al. Guidelines for the management of aneurysmal subarachnoid hemorrhage: a guideline for healthcare professionals from the American Heart Association/American Stroke Association. Stroke 2012; 43: 1711-37.

[16] Morgenstern LB, Hemphill JC III, Anderson C, Becker K, Broderick JP, Connolly ES, et al. Guidelines for the management of spontaneous intracerebral hemorrhage: a guideline for healthcare professionals from the American Heart Association/American Stroke Association. Stroke 2010; 41: 2108-29.

[17] Khan SN, Vohra EA. Risk factors for stroke: a hospital based study. Pak J Med Sci 2007; 23(1): 17-22.

[18] Broderick J, Connolly S, Feldmann E, Hanley D, Kase C, Krieger D, et al. Guidelines for the management of spontaneous intracerebral hemorrhage in adults 2007 update: a guideline from the American Heart Association/American Stroke Association Stroke Council, High Blood Pressure Research Council, and the Quality of Care and Outcomes in Research Interdisciplinary Working Group. Stroke 2007; 38: 2001-23.

[19] Ferro JM. Update on cerebral haemorrhage. J Neurol 2006; 253: 985-99.

[20] Hänggi D, Steiger HJ. Spontaneous intracerebral haemorrhage in adults: a literature overview. Acta Neurochir (Wien) 2008; 150(4): 371-9.

doi:Medical emergency research 10.1016/j.joad.2015.07.002

*Corresponding author:Lomati Venkata Pavan Kumar Reddy, Department of Clinical Pharmacy, P. Rami Reddy Memorial College of Pharmacy, Kadapa 516003, India.

Journal of Acute Disease2015年3期

Journal of Acute Disease2015年3期

- Journal of Acute Disease的其它文章

- Diagnosis of chronic myeloid leukemia from acute intracerebral hemorrhage: a case report

- Analysis of cases caused by acute spider bite

- Evaluation of the safety profile and antioxidant activity of fatty hydroxamic acid from underutilized seed oil of Cyperus esculentus

- Therapeutic potential of bryophytes and derived compounds against cancer

- DPOAE measurements in comparison to audiometric measurements in hemodialyzed patients

- Successful application of acute cardiopulmonary resuscitation