Analysis of cases caused by acute spider bite

Zihni Sulaj, Gentian Vyshka, Amarda GashiUniversity Hospital Center ‘Mother Theresa’, Tirana, AlbaniaFaculty of Medicine, University of Medicine, Tirana, Albania

Analysis of cases caused by acute spider bite

Zihni Sulaj1, Gentian Vyshka2*, Amarda Gashi1

1University Hospital Center ‘Mother Theresa’, Tirana, Albania

2Faculty of Medicine, University of Medicine, Tirana, Albania

ARTICLE INFO ABSTRACT

Article history:

Received 2 Mar 2015

Received in revised form 7 Mar 2015 Accepted 5 Apr 2015

Available online 10 Jul 2015

Keywords:Spider bite Pain

Hypertension Diagnosis

Rate

Mortalities

We performed a retrospective study of 176 patients in the University Hospital Center of Tirana (Albania), during the period 2001-2011, admitted with the diagnosis of a suspected spider bite. Three fatalities were registered during this decade covered from our study, with a clinical picture of marked hypertension, tachycardia and acute cardiac failure leading to death within a minimum of 25 hours and a maximum of 42 hours from the occurrence. Out of the total of 176 patients, we had 59% (104 cases) females, and 41% males. The overwhelming majority of the patients lived in rural areas (155 of the cases); extremities were mostly affected from the bites. A summary of clinical signs and a brief review of the available literature are made in the results and discussion section of this paper. Authors advocate that special precautions should be taken especially in severe forms of interesting autonomous nerve system, with aggressive fluid resuscitation, supportive therapy and close monitoring of vital signs.

E-mail: gvyshka@gmail.com

1. Introduction

Creatures that inject or secrete poisonous fluids are a cause of significant morbidity and mortality on a global scale[1]. These creatures are categorized as poisonous if they possess a special apparatus to inject the poison. Many spiders produce toxic venoms that can cause skin lesions, systemic illnesses, neurotoxicity, and death.

However, the majority of the bites among humans are unintentional and mostly harmless[2-4]. That human envenomation occurs at all, is the result of two factors: specific aggressive behavior and adaption to human environment. Understanding the venomous function and what mechanisms are involved in the fast evolutionary process of venom components is a major field of investigation[5]. However, in the evolutionary process, the spider venom has increased complexity to secure a bioactivity of a complex cocktail made of highly potent and selective ingredients that will affect a broad range of targets and offer the best adaptation to environmental changes.

The preferred collective term for envenoming spider bites is “araneism”[3].

The severity of the poisoning depends on the species of the spider, the type of bite, the level of toxicity in the injected poison, the amount of injected poison, the location of the bite and the health status of the bitten individual[6]. The clinical consequences are local and systemic, organic as well as psychological. Del Brutto describes three main syndromes caused by the poisoning of spider bites, namely, latrodectism, loxoscelism and the poisoning from spiders with funnel-like webs[7].

The distribution of medically important spiders is the most important factor in identification of where clinically important arachnoidism occurs throughout the world[8]. But, the epidemiologic analysis of spider bites is confounded by several factors, among others, suspected versus confirmed bites and stings, and lack of entomologic identification of biting arthropods[9]. As a result, spider envenomation and death resulting from spider bite in humans worldwide is unknown and more than likely under-represented[10].

Albania is located in a hotspot of biodiversity in the Mediterranean Basin which includes a rich fauna of spider species which are not fully studied[11,12]. The ways that the Black Widow Spiders (BWS),invades and develops in new habitats during the last decades both in Albania and in Europe have not been thoroughly studied[7,8].

Latrodectus tredecimguttatus (L. tredecimguttatus) or the Mediterranean widow occupies dry habitats, dunes, sandy beaches and on low vegetation[13]. Other mildly venomous spiders in Europe can be found in the Dysderidae family[14]. In the country, there are only anecdotic data on existence of the morbidity and even mortality concerning the spider envenomations. However, no systematic studies on incidence, epidemiology, clinical and demographic profile of victims of spider bite were conducted up to now.

2. Materials and methods

This is a retrospective descriptive study based on the data cumulated from registration forms and clinical files of the patients receiving hospital treatment in the period 2001-2011. The codes for the diagnoses i.e. ICD9 (E905.1, E906.4) were manually put together.

Study population included 176 subjects whose clinical documentation was more complete and the diagnosis was more credible. We excluded patients aged younger the 14 years, patients whose documentation was not clear for spider allegation and clinical cases where spider envenomation was not the primary condition for patient’s hospital treatment.

The study was conducted at the National Clinical Toxicology and Addictology Center, which specializes in the treatment of acute poisonings and overdoses and which is part of the “Mother Theresa”University Hospital Center in Tirana, Albania. Demographic data were recorded for each case of spider bite, including age, gender, place of residence, time of year and season, circumstances leading to the bite, time and date, as well as other typical clinical general and local data. All the above mentioned information was input into MS Excel 2007, spreadsheets and descriptive statistics were calculated.

The study included hospitalized patients aged 14 years or older for a total of 176 individuals whose clinical documentation was more complete and the diagnoses were more credible. The clinical documentation relating to the three fatal cases was discussed in thorough detail below.

3. Results

There were a total of 1 642 cases presented to ED due to biological and environmental poisonings from whom 608 cases were registered with a suspected or probable diagnosis of spider bites. Only 28.9% of them i.e. n = 176, were admitted for hospitalization, from whom 59% (104) were female and 40.9% (72) were male. Most of the subjects, 88% (155) lived in rural areas while 12% (22) lived in urban areas. In 78.4% of cases (n = 138) incidents happened outside the dwelling, in orchards, greenhouses and in cultivated fields; while only 4.8% were in-door bites. For the remaining 17% (30), there was no information on the circumstances leading to the bite. From the information that was available on patient files, in 76.1% (134) of cases, the most common sites of bites were the upper and lower extremities.

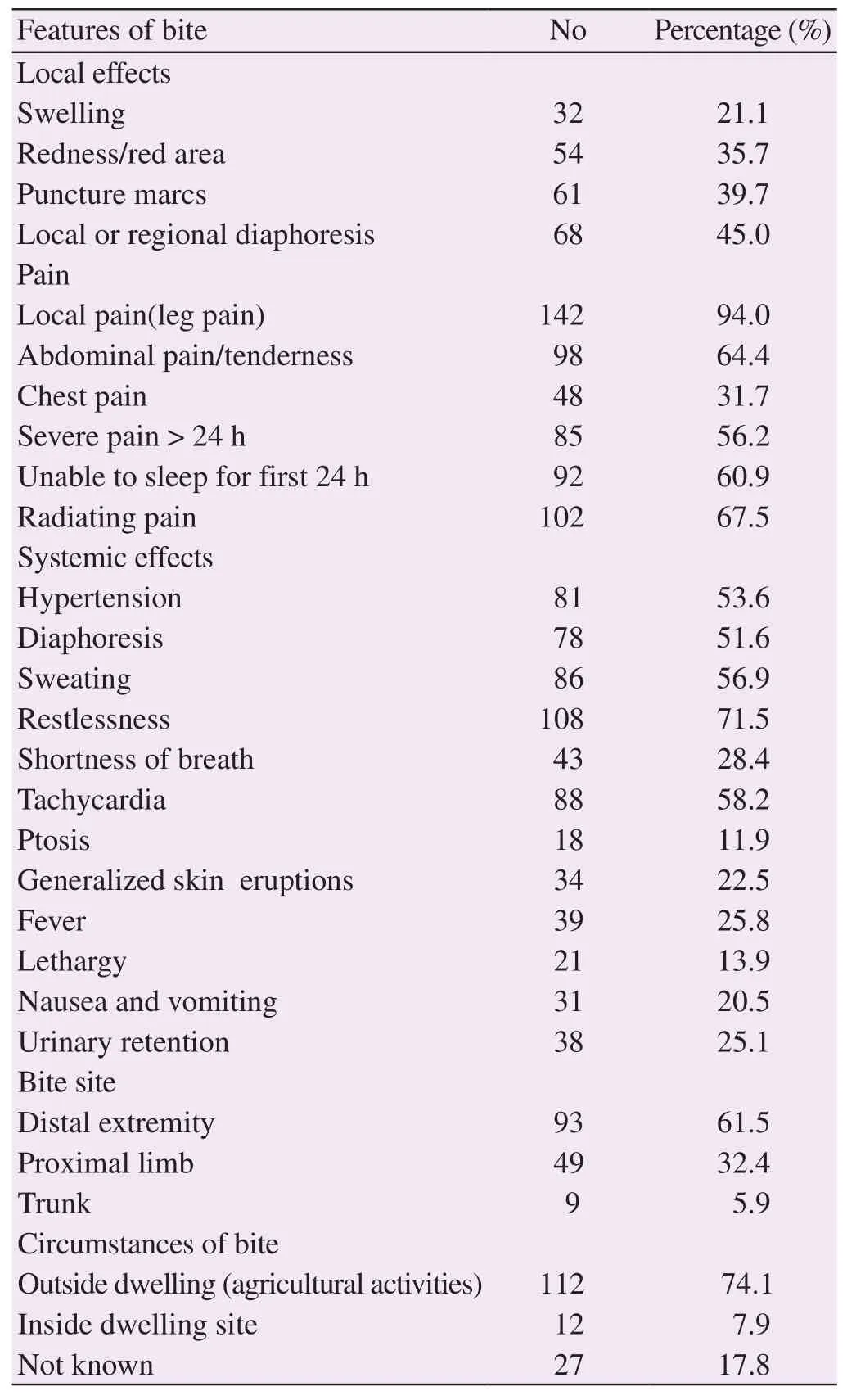

Based on notes found on patient’s files concerning the diagnosis of our patients cluster, in 85.7% (151) of cases it was a high probabilityfor a spider’s bite. In fact, in 13.4% (n = 22) of the cases, there were some types of description relating to the spider, but no one fulfilled the above criteria for a verified spider bite. The diagnosis at hospital discharge in 85.8% (n = 151) of the cases, was related with to BWS bites i.e. L. tredecimguttatus. It was impossible however to distinguish if any bites were coming from spp. steatoda spiders or fake BWS. In 7.3% (n = 13) of the cases, clinical files contained information on various skin lesions probably relating to bites from Loxosceles rufescens spiders of which 2% (n = 3) contained also descriptive information on necrosis of different sizes on the hands of patients. About 7% (n = 12) of all the cases, contained no clinical information regarding the possible involvement of spiders in suspected incidents apart from information on atypical skin lesions. Despite the difficulties in organizing and ranking the signs and symptoms of L. tredecimguttatus, spider bite (as presumably widow spider), as detailed in the patients’ clinical files, the most consistent symptoms are presented in Table 1.

Table 1Clinical profile of 151 probable spider bite victims.

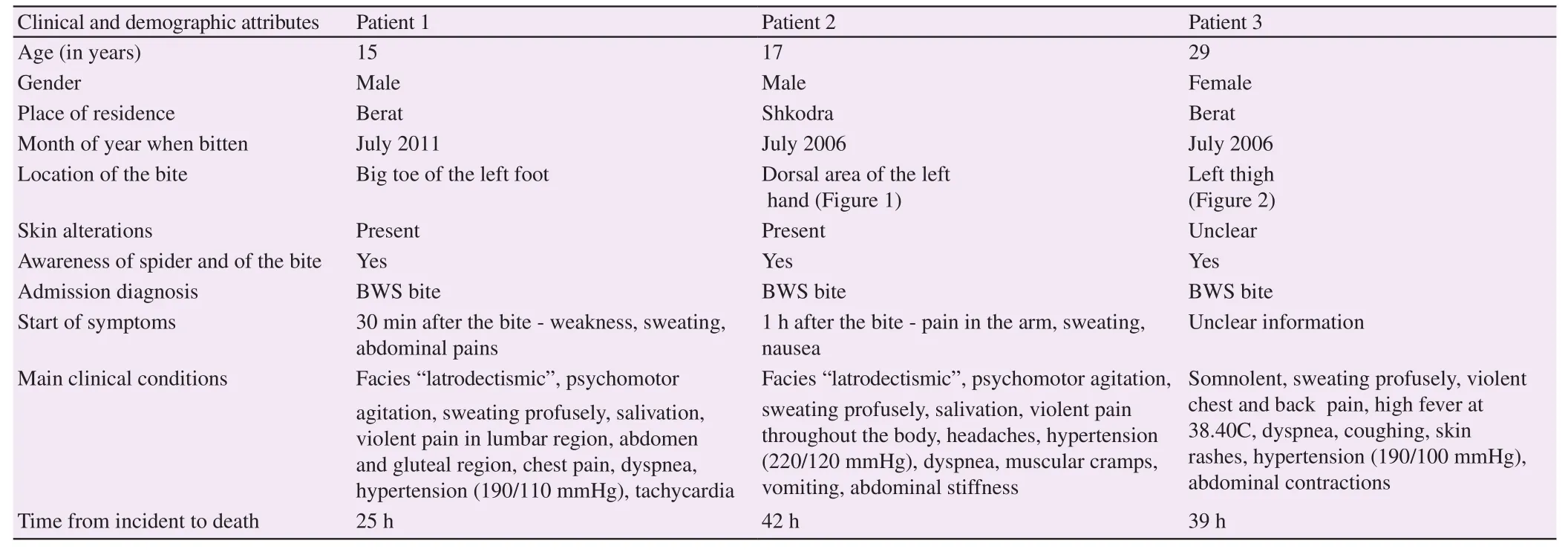

During the study period in 2001 - 2011, there were registered three fatal cases. Two of the cases were registered in July 2006 within one week from each other. The third case was registered in July 2011. Two of the cases originated from the Berat area, in the central-eastern part of the country whereas the third originated fromShkodra, in the northwest of the country.

The average age of the deceased was 20.33 (57.33) years. All three patients lived in rural communities. None of the individuals had any history of chronic diseases or any heart congenital defect anomalies from birth. Up to the moment of the bite, the three individuals had been perfectly healthy. Clinical symptoms, as it were described on patient’s files, in all three fatal poisoning cases were complex. Apart from the diffused violent pains, profuse sweating, muscular contractions, agitations, strong headaches, insomnia and anxiety, the symptoms were further complicated by the malignant hypertension, unresponsive to antihypertensive drugs, with a systolic blood pressure averaging 200 mmHg an average diastolic blood pressure of 110 mmHg, tachycardia, dyspnea, chest pain and acute cardiogenic pulmonary edema followed by cardio-respiratory arrest, as the final cause of death.

Table 2Clinical description of the three fatal spider bite cases.

Figure 1. Signs of black widow spider bite, back of left hand (2nd fatality case).

Figure 2. Signs of black widow spider bite, left pretibial region (3rd fatality case).

The clinical characteristics of the three fatal cases are summarized in Table 2.

4. Discussion

Our study, presumably the first of its kind in the country, despite its limitations and biases, evidences a clear significant morbidity related to the bites of these specific species of venomous spiders. As relatively new medical issue (the first case registered in 1999), they reflect country recent invasion history to the widow spider species, concretely L. tredecimguttatus which bites dominated the clinical picture in this case series.

The epidemiologic analysis of spider bites is confounded by several factors including the extensive differential diagnosis[3]. The correct diagnosis, in particular in retrospective studies is the most debatable issue among many authors[15,16].

Jung has stated that in the absence of evidence for the identification of the cause of poisoning, all efforts are focused on the main dilemma: if the implicated venom has an available antidote[8]. A verified spider bite diagnosis requires that the spider has to be collected while or immediately after biting, and an expert has to identify the spider itself[17,18].

Authors suggest that these conditions rarely coincide. Braitberg reported that spider identification was problematic and the clinician is better off in recognizing the ‘toxic syndrome’ than in attempting to identify the spider responsible for the bite[19].

There are no commercially available laboratory tests for identifying the presence of spider venom. Thus, the diagnosis is made clinically. Rapid identification of the spider involved, whether caught by the patient or not, and correlation with known effects of that spider group would allow appropriate early advice to patients[20]. But there are few available arachnologists, and the lengthy process required to identify the spiders means these cannot be identified for every patient at the time of the bite.

As in other reports in this study the crucial factors in reaching a probable diagnosis of spider bite, mostly latrodectism were the knowledge and experience of clinical toxicologists , epidemiological features, typical seasonal distribution and occurrence in farming andoutdoor activities[21-23]. The case history is one of the most important elements, forming the essential basis for a plausible assessment of a case of disease, especially when the lack of knowledge in the spider semiology is present[22]. However, in retrieving the patient’s history one should be vigilant because most victims’ reports of spider bites are unreliable[21].

From our study, we think that the lack of information and awareness, and similarities in pain and other sensations of spider biting with other biological or physical causes during farming and open air activities had caused the insufficient noticing and collection of them.

Authors have reported that medical staff should always consider a spider bite in the differential diagnosis of unexplained autonomic and neurological dysfunction, particularly in children[20]. At the contrary, multiple lesions or more than one lesion on widely-separated parts of the body will suggest another etiology, since spider bites are typically single lesions. Furthermore, bites are generally not simultaneously sustained by multiple residents of the same household.

In our case series of probable spider bite, we found out that not all alleged cases of spider bites were actually accurate. Such cases anyhow should be urgently treated by taking in consideration other pathologies as well. The patients who display signs and symptoms suggesting a spider bite of the Latrodectus spp. where pain is present overall must be observed and treated mainly with symptomatic drugs for at least 6 to 8 h. Although patient deaths are rare, our incidence has been 1.7%.

Precautions should be taken especially in severe forms affecting vegetative nerve functions and the heart. In such cases, it is advisable to perform a close cardiac monitoring. The enzymes affecting the myocardium should also be evaluated on a regular basis. Latrodectus antivenin should be available at all times and should be applied correctly based on the risk-benefit concept. The antivenin, regardless of its relative high cost, would have probably saved the lives of the three unfortunate victims of the incidents we referred to in this study. In addition, the education of medical staff on diagnostic and therapeutic criteria and the public information aimed at residents of rural areas during summer months in order to highlight preventive measures with poisonous spiders are important and achievable measures in the short-term perspective.

Conflict of interest statement

The authors report no conflict of interest.

References

[1] White J. Bites and stings from venomous animals: a global overview. Ther Drug Monit 2000; 22(1): 65-8.

[2] Weinstein SA, Dart RC, Staples A. Envenomations: an overview of clinical toxinology for the primary care physician. Am Fam Physician 2009; 80(8): 793-802.

[3] Diaz JH. The global epidemiology, syndromic classification, management, and prevention of spider bites. Am J Trop Med Hyg 2004; 71(2): 239-50.

[4] Saucier JR. Arachnid envenomation. Emerg Med Clin North Am 2004; 22(2): 405-22, ix.

[5] Kuhn-Nentwig L, Stöcklin R, Nentwig W. Venom Composition and Strategies in Spiders: Is Everything Possible? Adv In Insect Phys 2011; 40: 1-86.

[6] Bury D, Langlois N, Byard RW. Animal-related fatalities-part II: characteristic autopsy findings and variable causes of death associated with envenomation, poisoning, anaphylaxis, asphyxiation, and sepsis. J Forensic Sci 2012 ; 57(2): 375-80.

[7] Del Brutto OH. Neurological effects of venomous bites and stings: snakes, spiders, and scorpions. Handb Clin Neurol 2013; 114: 349-68.

[8] Junghanss T, Bodio M. Medically important venomous animals: biology, prevention, first aid, and clinical management. Clin Infect Dis 2006; 43(10): 1309-17.

[9] Isbister GK, Fan HW. Spider bite. Lancet 2011; 378(9808): 2039-47.

[10] Diaz JH, Leblanc KE. Common spider bites. Am Fam Physician 2007; 75(6): 869-73.

[11] Nicholson GM, Graudins A. Antivenoms for the treatment of spider envenomation. Toxin Reviews 2003; 22: 35-59.

[12] Vrenozi B. A collection of spiders (Araneae) in Albanian coastal areas. Arachnologische Mitteilungen 2012; 44: 41-6.

[13] Le Peru B. The spiders of Europe, a synthesis of data: Volume 1 Atypidae to Theridiidae. Société Linnéenne de Lyon 2011; 1: 1-522.

[14] Bodio M, Junghanss T. [Accidents with venomous and poisonous animals in Central Europe]. Ther Umsch 2009; 66(5): 349-55. German.

[15] Vetter RS, Isbister GK, Bush SP, Boutin LJ. Verified bites by yellow sac spiders (genus Cheiracanthium) in the United States and Australia: where is the necrosis? Am J Trop Med Hyg 2006; 74(6): 1043-8.

[16] Goddard J. Physician’s Guide to arthropods of medical importance. 6th ed. New York: CRC Press; 2012.

[17] Nentwig W, Gnädinger M, Fuchs J, Ceschi A. A two year study of verified spider bites in Switzerland and a review of the European spider bite literature. Toxicon 2013; 73: 104-10.

[18] Isbister GK, Sibbritt D. Developing a decision tree algorithm for the diagnosis of suspected spider bites. Emerg Med Australas 2004; 16(2): 161-6.

[19] Braitberg G, Segal L. Spider bites - Assessment and management. Aust Fam Physician 2009; 38(11): 862-7.

[20 Isbister GK, Gray MR. A prospective study of 750 definite spider bites, with expert spider identification. QJM 2002; 95(11): 723-31.

[21] Dzelalija B, Medic A. Latrodectus bites in northern Dalmatia, Croatia: clinical, laboratory, epidemiological, and therapeutical aspects. Croat Med J 2003; 44(2): 135-8.

[22] Díez García F, Laynez Bretones F, Gálvez Contreras MC, Mohd H, Collado Romacho A, Yélamos Rodríguez F. [Black widow spider (Latrodectus tredecimguttatus) bite. Presentation of 12 cases]. Med Clin (Barc) 1996; 106(9): 344-6. Spanish.

[23] Vetter RS, Cushing PE, Crawford RL, Royce LA. Diagnoses of brown recluse spider bites (loxoscelism) greatly outnumber actual verifications of the spider in four western American states. Toxicon 2003; 42(4): 413-8.

doi:Short communication 10.1016/j.joad.2015.04.013

*Corresponding author:Gentian Vyshka, Faculty of Medicine, University of Medicine, Tirana, Albania.

Journal of Acute Disease2015年3期

Journal of Acute Disease2015年3期

- Journal of Acute Disease的其它文章

- Diagnosis of chronic myeloid leukemia from acute intracerebral hemorrhage: a case report

- Evaluation of the safety profile and antioxidant activity of fatty hydroxamic acid from underutilized seed oil of Cyperus esculentus

- Therapeutic potential of bryophytes and derived compounds against cancer

- Risk factors for medical complications of acute hemorrhagic stroke

- DPOAE measurements in comparison to audiometric measurements in hemodialyzed patients

- Successful application of acute cardiopulmonary resuscitation