Successful application of acute cardiopulmonary resuscitation

Derya Öztürk, Ertuğrul Altinbilek, Murat Koyuncu, Bedriye Müge Sönmez, Çilem Çaltili, Ibrahim Ikzcel, Cemil Kavalci, Gülsüm KavalciEmergency Department, Şişli Etfal Training and Research Hospital, İstanbul, TurkeyEmergency Department, Faculty of Medicine, Karabük University, Karabük, TurkeyEmergency Department, Numune Training and Research Hospital, Ankara, TurkeyEmergency Department, Faculty of Medicine, Baskent University, Ankara, TurkeyAnesthesia Dapartment, Yenimahalle State Hospital, Ankara, Turkey

Successful application of acute cardiopulmonary resuscitation

Derya Öztürk1, Ertuğrul Altinbilek1, Murat Koyuncu2, Bedriye Müge Sönmez3, Çilem Çaltili1, Ibrahim Ikzcel1, Cemil Kavalci4*, Gülsüm Kavalci5

1Emergency Department, Şişli Etfal Training and Research Hospital, İstanbul, Turkey

2Emergency Department, Faculty of Medicine, Karabük University, Karabük, Turkey

3Emergency Department, Numune Training and Research Hospital, Ankara, Turkey

4Emergency Department, Faculty of Medicine, Baskent University, Ankara, Turkey

5Anesthesia Dapartment, Yenimahalle State Hospital, Ankara, Turkey

ARTICLE INFO ABSTRACT

Article history:

Received 6 Apr 2015

Received in revised form 8 Apr 2015 Accepted 23 Apr 2015

Available online 8 Jul 2015

Keywords:

Cardiopulmonary arrest

Emergency Department

Cardiopulmonary resuscitation

Objective: To compare the quality and correct the deficiencies of cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR) procedures performed in patients who developed cardiopulmonary cardiopulmonary arrest before or after Emergency Department admission.

Methods: This study was conducted on patients who were applied CPR atŞŞişli Etfal Training and Research and Research Hospital, Emergency Department between 01 January 2012 and 31 December 2012. Chi-square and Mann-Whitney U test were used to compare the patients' data. The study data were analyzed in SPSS 18.0 software package. A P value less than 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results: A total of 155 patients who were applied CPR were included in the analysis. Among the study patients, seventy eight (50.3%) were brought to Emergency Department after developing cardiopulmonary arrest while 77 (49.7%) developed cardiopulmonary arrest at Emergency Department. The mean age of the study population was (66 ± 16) years and 64% of the patients were male. The initial rhythms of the CPR-applied patients were different (P < 0.05). There were no significant differences between the groups with respect to the treatment protocols or CPR responses (P > 0.05). The CPR response time was longer in ED (P < 0.05). The survival rate was lower in the trauma patients who developed cardiopulmonary arrest at ED(P < 0.05).

Conclusions: The scientific data obtained in this study suggest that an early response and therapy improves outcomes in CPR procedure.

Tel: +90 312 212 6868

E-mail: cemkavalci@yahoo.com

1. Introduction

Cardiopulmonary cardiopulmonary arrest is defined as sudden cessation of respiration and cardiac activity[1]. Cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR) is composed of establishing an effective airway, providing adequate ventilation, and delivering cardiac massages with appropriate medical and equipment support[2]. The CPR procedure is considered successful when the goal of obtaining a regular pulse and a decent blood pressure is achieved. A successful CPR is an intense professional satisfaction for the physician while it is invaluable for the patient and relatives.

The idea that death can be reversed has long drawn attention of humans and different techniques have been tried to achieve that goal. The first CPR procedure was performed by Kowenhoun in 1960 since when updated guidelines have been published every 5 years to correct deficiencies in the science of CPR[3]. Finally, a CPR guideline published in 2010 brought about radical changes in that field[4].

We aimed to compare the CPR procedures and treatment protocols in patients who developed before or during Emergency Department (ED) admission in an attempt to overcome our deficiencies in that field.

2. Materials and methods

This prospective study was approved by the local ethics committee and conducted on 155 patients who were applied CPR at Şişli Etfal Training and Research Hospital, Emergency Medicine Clinicbetween 01 January 2012 and 31 December 2012.

Interventions that were carried out on 155 patients at ED were scrutinized in the light of the current guidelines. Age, sex, duration of basic life support, rhythms at cardiopulmonary arrest onset, trauma history, CPR duration, time to CPR response in CPR responders, medications used during CPR effort, the number of defibrillations if performed, final diagnoses, and outcomes of CPR procedures were compared in this evaluation.

The study data were presented as the patient number (n), percentage (%), and arithmetic mean ± SD. The patients were divided into 2 groups as those who developed cardiopulmonary arrest at ED and those who developed cardiopulmonary arrest prior to ED admission. The groups were compared with χ2for categoric variables and with Mann-Whitney U test for continuous variables. The study data were analyzed in SPSS 18.00 for Windows software package. A patients value less than 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

3. Results

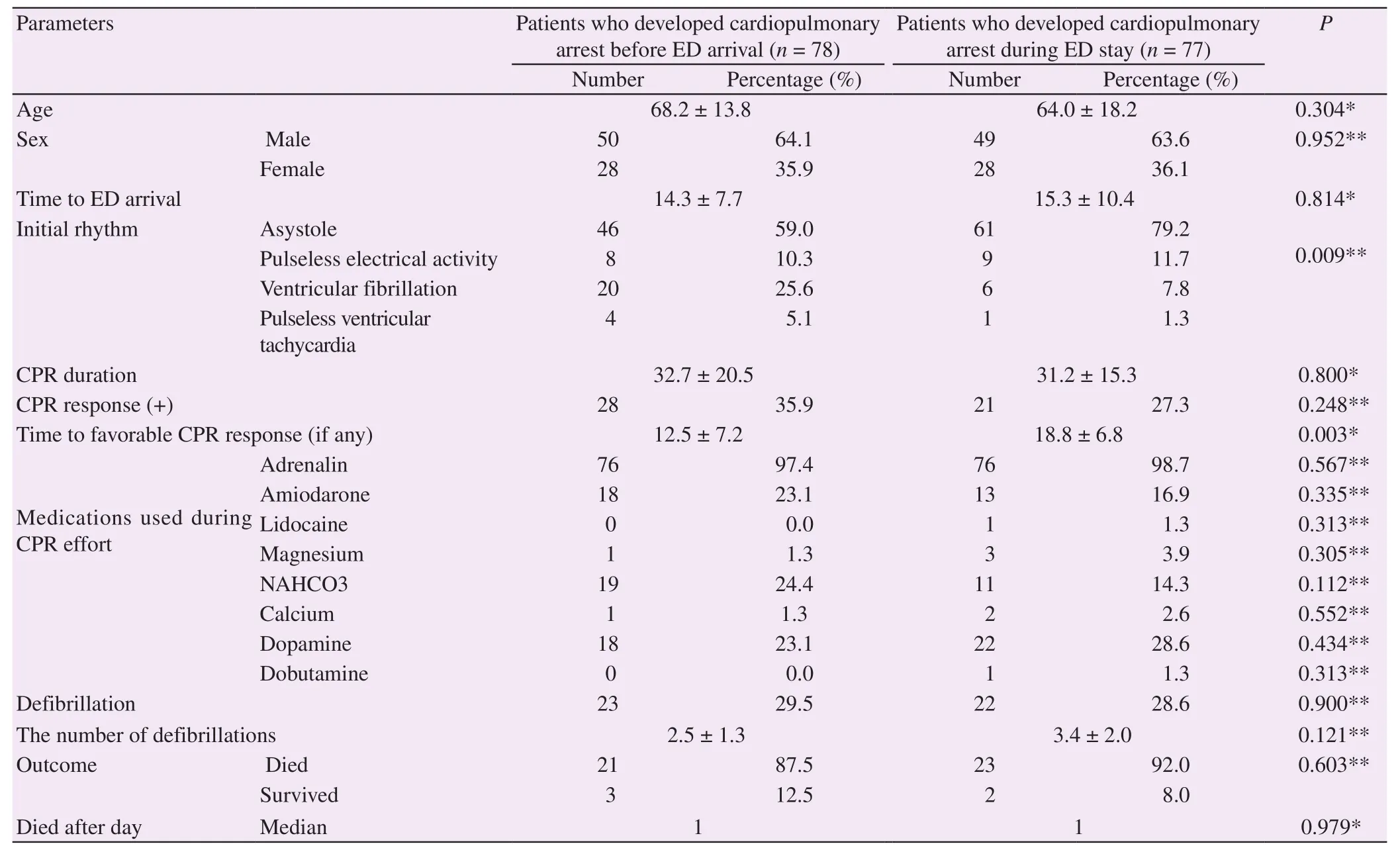

A total of 155 patients who were applied CPR were included in this study. Among the study population, 78 (50.3%) were brought to ED after cardiopulmonary arrest, while 77 (49.7%) developed cardiopulmonary arrest at ED. The demographic properties by the groups were summarized in Table 1. The mean age of the population was (66 ± 16) years and 64% of the patients were male. There were no significant differences between the groups with respect to age and sex (P > 0.05).

Table 1Demographic variables and differences between the patient clinics with respect to the CPR application.

*: Mann-Whitney U test; **: χ2test; Value was expressed as mean ± SD.

The average duration of ED transport was 15 min. The mean duration of CPR application was 32 min. A total of 49 (31.6%) patients responded to CPR, of whom 28 developed cardiopulmonary arrest prior to ED admission and 21 developed cardiopulmonary arrest during ED stay. The mean time to CPR response was 12.5 min in the patients who were already in cardiopulmonary arrest at the time of ED admission and 18.8 min in those who developed cardiopulmonary arrest during ED stay. No significant differences were found between the groups with regard to the time to ED admission, mean CPR duration, and the rate of CPR response (P > 0.05). The time to CPR response was significantly greater in the group that developed cardiopulmonary arrest at ED (P < 0.05). Adrenalin was the most commonly administered drug (98.1%) followed by dopamine (25.8%) during CPR. The groups did not significantly differ with respect to the administered therapy during CPR (P > 0.05). Forty-three patients who responded to CPR efforts re-developed cardiopulmonary arrest that did not respond to CPR. As a result, 5 patients were discharged. There were no significant differences between both groups with respect to the time to recurrent CPR and discharge rate (P > 0.05) (Table 1).

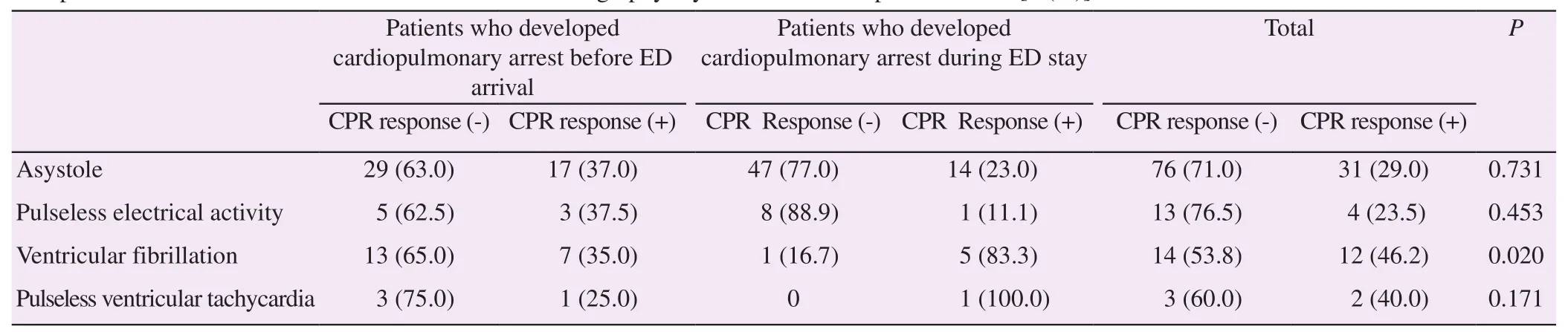

The most common cause of cardiopulmonary arrest was asystole in both groups. The cardiopulmonary arrest rhythms of the two groups were summarized in Table 2. There was a significant difference between the two groups with respect to the cardiopulmonary arrest rhythms (P < 0.05). No significant differences existed between the two groups with respect to the outcomes of the interventions against asystole, pulseless electrical activity, and pulseless ventricular tachycardia (P > 0.05). The intervention against ventricularfibrillation that developed at ED was more successful (P < 0.05) (Table 2).

The most common diagnoses as the cause of cardiopulmonary arrest were acute coronary syndrome and left heart failure (Table 3). With an exception for traumatic cardiopulmonary arrest, no significant difference was detected between the patient diagnoses and developing cardiopulmonary arrest before and after ED arrival (P > 0.05). Three of the patients with traumatic cardiopulmonary arrest were already in cardiopulmonary arrest when brought to ED, 11 patients developed cardiopulmonary arrest at ED, and less patients with traumatic cardiopulmonary arrest responded favorably to CPR (P < 0.05) (Table 3).

Patients who developed cardiopulmonary arrest before ED arrival Patients who developed cardiopulmonary arrest during ED stay Total P CPR response (-) CPR response (+) CPR Response (-) CPR Response (+) CPR response (-) CPR response (+) Asystole 29 (63.0) 17 (37.0) 47 (77.0) 14 (23.0) 76 (71.0) 31 (29.0) 0.731 Pulseless electrical activity 5 (62.5) 3 (37.5) 8 (88.9) 1 (11.1) 13 (76.5) 4 (23.5) 0.453 Ventricular fibrillation 13 (65.0) 7 (35.0) 1 (16.7) 5 (83.3) 14 (53.8) 12 (46.2) 0.020 Pulseless ventricular tachycardia 3 (75.0) 1 (25.0) 0 1 (100.0) 3 (60.0) 2 (40.0) 0.171

χ2test; CPR response (-): No CPR response; CPR response (+): CPR response.

4. Discussion

Response to cardiopulmonary arrest depends on many factors. Among them, the most important one is the early and high-quality CPR[4]. A CPR effort especially within the first 3–4 min is lifesaving[5]. Previous studies have reported that 15% to 38% of patients respond to CPR[5-7].

Previous studies reported a mean age of 63.8 years and a male percentage of 54.5% in 4 789 patients who were applied CPR[3,8]. Oğuztürk et al., in a 70-patient study, reported a mean age of 63.4 years a mean percentage of 58.6%[2]. In our study the mean age of the study population was 66.1 years and 63.9% of our patients were male. The age and sex distribution of the patients admitted to ED because of cardiopulmonary arrest were consistent withthe literature. The reason of the male predominance in our study may be a lower incidence of cardiac and renal disorders in women and men spending more time outdoors and driving more commonly than women, increasing their susceptibility to accidental injuries.

Shockable rhythms constitute the majority of rhythms during cardiopulmonary arrest and such rhythms respond to CPR in a most favorably manner[2,3,6]. Studies before 2005 have shown that the survival rates were low in out-of-hospital ventricular fibrillation and it has been attempted to take necessary measures[8]. We also observed shockable rhythms more commonly than other rhythms. It was observed in our study that patients responded to interventions to a large extent in ventricular fibrillations which was developed at ED. The patients are under constant physician supervision and monitor at EDs and thus any ventricular fibrillation that develops gets instantly diagnosed and appropriately managed via defibrillation. We therefore believe that response to CPR is better in such circumstances. We also think that the outcomes of ventricular fibrillations that develop in ambulances before ED admission are poor since ambulances in Turkey are not equipped with physicians but other healthcare staff who sometime may fail or delay to recognize and manage shockable rhythms.

Literature data suggest that patients respond favorably to CPR when CPR is initiated in a short time. Conversely, CPR procedures exceeding 15 min are associated with a patient death rate exceeding 95%; CPR efforts in an excess of 30 min are not compatible with survival[9]. In compliance with current scientific knowledge, we performed CPR for approximately 30 min in both patients brought to ED after cardiopulmonary arrest and those who developed cardiopulmonary arrest at ED. In those who were responsive to CPR, the time to response to CPR was longer in those who developed cardiopulmonary arrest at ED. This may be the consequence of the longer survival expectation in witnessed cardiopulmonary arrest at ED.

Table 3Comparison of the interventions between the patient diagnoses and clinics [n (%)].

CPR response (-): No CPR response; CPR response (+): CPR response.

Literature data about CPR indicates that CPR response rate ranges between 15% and 38% and it is affected by comorbid conditions[3-5]. Particularly, terminal stage cancers and other irreversible diseases reduces rates of CPR response[1]. The rate of CPR response in our study was 31.6%, being higher for cardiopulmonary arrests developing prior to ED admission, possibly because professional ambulance staff are employed in Turkey.

The latest CPR guidelines published in 2010 suggested the use of supplemental drugs in addition to vasopressors in specific circumstances[8]. We believe that there was no difference between the groups having cardiopulmonary arrest before vs after ED admission with respect to medications used and use of defibrillation because we apply all interventions in compliance with the most current guidelines and standards. Nevertheless, it is noteworthy that defibrillation was frequently used despite a low rate of shockable rhythms. This may be due to conversion of rhythm from asystole to ventricular fibrillation during CPR.

Literature data suggest that pathologies of cardiac origin are the major cause of cardiopulmonary arrest[10-16]. The rate of response of trauma-induced cardiopulmonary arrests to CPR is below 5%[17]. In line with the literature, the major causes of cardiopulmonary arrest in our study were of cardiac origin. We observed that trauma victims differed from other patients with regard to their CPR response. We are of the opinion that this difference primarily resulted from the progressively deteriorating hemodynamic stability of trauma patients after arrival at ED, which rendered them unresponsive to CPR.

Kozacı et al. reported that 5% of their patients survived to discharged after CPR[18]. Ayrık pointed that the survival rate of out-of-hospital cardiac arrests is below 6% and it is higher in developed countries. Outcomes of CPR are poor, with only 3% of patients being able to survive until hospital discharge[19]. This grave prognosis may be linked to a delay in patient transport, CPR-related complications, and post-CPR complications including infections, electrolyte deficiencies etc.

In conclusion, an early response to and timely interventions against cardiopulmonary arrest are associated with favorable outcomes associated with CPR.

Conflict of interest statement

The authors report no conflict of interest.

References

[1] Leong BSH. Bystander CPR and survival. Singapore Med J 2011; 52: 573-5.

[2] Oğuztürk H, Turgay MG, Tekin YK, Sarıhan E. Our experiences with the in hospital cardiac arrests and their resuscitations. Kafkas J Med Sci 2011; 1: 114-7.

[3] Herlitz J, Rundqvist S, Bång A, Aune S, Lundström G, Ekström L, et al. Is there a difference between women and men in characteristics and outcome after in hospital cardiac arrest? Resuscitation 2001; 49: 15-23.

[4] van Walraven C, Forster AJ, Parish DC, Dane FC, Chandra KM, Durham MD, et al. Validation of a clinical decision aid to discontinue in-hospital cardiac cardiopulmonary arrest resuscitations. JAMA 2001; 285: 1602-6.

[5] Wallace SK, Abella BS, Shofer FS, Leary M, Agarwal AK, Mechem CC, et al. Effect of time of day on prehospital care and outcomes after out-of-hospital cardiac cardiopulmonary arrest. Circulation 2013; 127: 1591-6.

[6] Danciu SC, Klein L, Hosseini MM, Ibrahim L, Coyle BW, Kehoe RF. Apredictive model for survival after in-hospital cardiopulmonary cardiopulmonary arrest. Resuscitation 2004; 62: 35-42.

[7] Finn JC, Jacobs IG, Holman DJ. Oxer HF. Outcomes of out of hospital cardiac cardiopulmonary arrest patients in Perth, Western Australia, 1996-1999. Resuscitation 2001; 51: 247-55.

[8] Field JM, Hazinski MF, Sayre MR, Chameides L, Schexnayder SM, Hemphill R, et al. Part 1: executive summary: 2010 American Heart Association guidelines for cardiopulmonary resuscitation and emergency cardiovascular care. Circulation 2010; 122(Suppl 3): S640-56.

[9] Hamill RJ. Resuscitation: when is enough, enough? Respir Care 1995; 40: 515-27.

[10] Sandroni C, Ferro G, Santangelo S, Tortora F, Mistura L, Cavallaro F, et al. In hospital cardiac arrest: survival depends mainly on the effectiveness of the emergency response. Resuscitation 2004; 62: 291-7.

[11] Westfal RE, Reissman S, Doering G, Out of hospital cardiac arrests: an 8 year New York City experience. Am J Emerg Med 1996; 14: 364-8.

[12] Kette F, Sbrojavacca R, Rellini G, Tosolini G, Capasso M, Arcidiacono D, et al. Epidemiology and survival rate of out-ofhospital cardiyac arrest in north-east Italy: the F.A.C.S. study. Friuli Venezia Giulia cardiac arrest cooperative study. Resuscitation 1998; 36: 153-9.

[13] Huang Y, He Q, Yang LJ, Liu GJ, Jones A. Cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR) plus delayed defibrillation versus immediate defibrillation for out-of-hospital cardiac arrest. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2014; doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD009803.pub2.

[14] Dumas F, Bougouin W, Geri G, Lamhaut L, Bougle A, Daviaud F, et al. Is epinephrine during cardiac arrest associated with worse outcomes in resuscitated patients? J Am Coll Cardiol 2014; 64(22): 2360-7.

[15] Yang HJ, Kim GW, Kim H, Cho JS, Rho TH, Yoon HD, et al. Epidemiology and outcomes in out-of-hospital cardiac arrest: a report from the NEDIS-based cardiac arrest registry in Korea. J Korean Med Sci 2015; 30: 95-103.

[16] Chan PS, McNally B, Tang F, Kellermann A, CARES Surveillance Group. Recent trends in survival from out-of-hospital cardiac arrest in the United States. Circulation 2014; 130: 1876-82.

[17] Alanezi K, Alanzi F, Faidi S, Sprague S, Cadeddu M, Baillie F, et al. Survival rates for adult trauma patients who require cardiopulmonary resuscitation. Can J Emerg Med 2004; 6: 263-5.

[18] Kozacı N, Ay MO, İçme F, Aktürk A, Satar S. Are we successful in cardiopulmonary resuscitation? Cukurova Med J 2013; 38: 601-9.

[19] Ayrik C. CPR and ECC guideline changes: “ACLS 2005 update”. [Online] Available from: http://old.tkd.org.tr//cg/ikyd/?p=CPR_ECC [Accessed on 8 April, 2015]

doi:Medical emergency research 10.1016/j.joad.2015.04.007

*Corresponding author:Cemil Kavalci, Emergency Department, Faculty of Medicine, Baskent University, Ankara, Turkey.

Journal of Acute Disease2015年3期

Journal of Acute Disease2015年3期

- Journal of Acute Disease的其它文章

- Diagnosis of chronic myeloid leukemia from acute intracerebral hemorrhage: a case report

- Analysis of cases caused by acute spider bite

- Evaluation of the safety profile and antioxidant activity of fatty hydroxamic acid from underutilized seed oil of Cyperus esculentus

- Therapeutic potential of bryophytes and derived compounds against cancer

- Risk factors for medical complications of acute hemorrhagic stroke

- DPOAE measurements in comparison to audiometric measurements in hemodialyzed patients