Chinese Traditional Music Revival

By+staff+reporter+LU+RUCAI

THE closing concert on November 22, 2014 of the second Beijing Huqin Music Festival at the Central Conservatory of Music played to a capacity audience. The concert presented, under the theme of “fusion,” 13 pieces under 11 program items. China Conservatory erhu player Zhang Zunlian raised the curtain with his rendition of the Autumn Moon over the Han Palace. Three generations of erhu artists, represented by Liu Changfu, Chen Yaoxing, Chen Jun, Zhou Wei, and Zhu Changyao, evoked the distinct charisma of this strain of traditional Chinese music. Liu Changfus performance of The Moon Mirrored in the Pool, in particular, reflected the spirit of its composer Hua Yanjun (also known as Blind A-Bing). The concluding piece Zigeunerweisen, (Gypsy Airs, a musical composition for violin and orchestra by Spanish composer Pablo de Sarasate) adapted for the erhu and played as a quartet by Yan Jiemin, Yang Xue, Zhao Yuanchun, and Wang Ying, brought the house down.

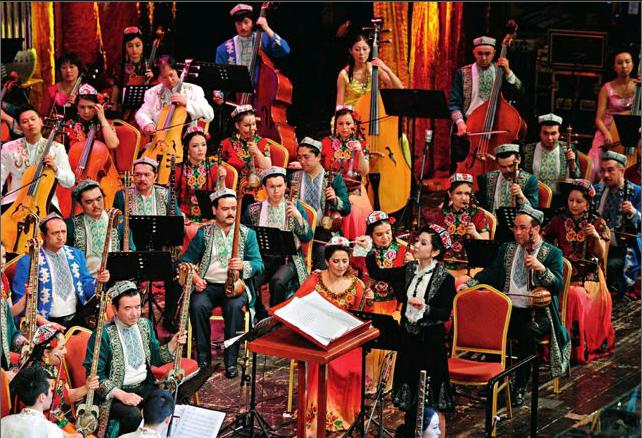

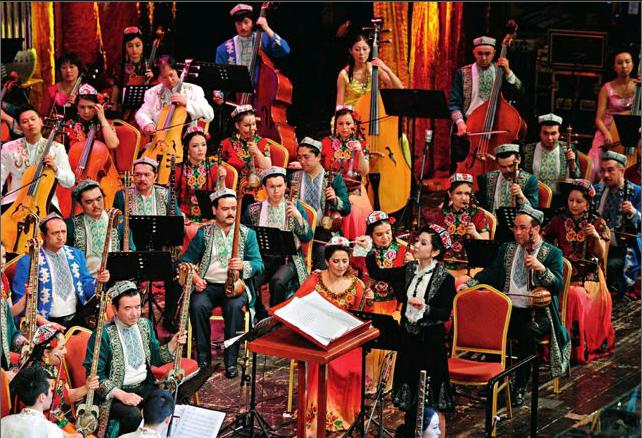

Chinese traditional folk music concerts are steadily gaining popularity. The China Central Nationalities Orchestras Impression of Chinese Music, for instance, has over the past 12 months been a big hit in several big cities.

Traditional Music Revivification

Based on a folk song choir and an orchestra specializing in traditional Chinese music of the former Central Ensemble of Songs and Dances, China National Orchestra was established in 1960. Lin Mohan, then deputy Minister of Culture, had high hopes that it would“reform Chinese folk musical instruments and promote national music.”

Folk music consequently is and always has been the orchestras focus. Its musicians have been to Xian in Shaanxi Province and Zhoushan in Zhejiang Province, respectively to research drum music and gong and drum music. They have also conducted studies in Jiangsu on the traditional string and woodwind instruments popular in regions south of the Yangtze River. This methodology continues to this day. The orchestra has established contacts in towns and villages through which to collect folk music. In recent years, traditional orchestral music concerts have been warmly received by audiences, Beautiful Xinjiang and Tibet in Spring in particular. The orchestra has launched projects and organized events aimed specifically at promoting traditional Chinese music.

The orchestra also brings traditional Chinese music to the world. China National Orchestra held concerts in Viennas Golden Hall in 1998, 1999 and 2010. In 2003 its performance at the opening ceremony of the Chinese Culture Year in France marked the start there of a national tour. During the Beijing Olympic Games in 2008, the orchestra performed a concert of Chinese national music for visiting heads of state at the Great Hall of the People, and in 2013 did a performance tour of several U.S. cities. The China National Orchestra repertoire now includes signature concerts that have established its international reputation.endprint

Chinese folk musicians observed Western orchestral techniques in the 1920s and 1930s while at the same time bearing in mind the characteristics of traditional Chinese musical instruments. This set the stage for a large-scale na- tional music orchestra comprising wind, percussion, and bowed and plucked string instruments. A good number of the national orchestras founded after the establishment in 1949 of the Peoples Republic of China, including the Shanghai Chinese Orchestra, China Broadcasting National Orchestra and Guangdong National Orchestra, were tasked with developing traditional music.

A large orchestra generally comprises 50 to 80 members, while those in the provinces usually have 20 to 30. Smaller orchestras in universities and secondary and primary schools have nurtured countless inheritors of traditional Chinese music. Amateur music groups playing erhu and other traditional musical instruments in parks and local neighborhoods are a common sight throughout the country.

Many outstanding players have appeared amid this traditional music revival. Liu Mingyuan, Liu Dehai, Wang Huiran, Wang Guotong, Wang Fandi, Min Huifen, Xiao Baiyong, Tang Liangxing, and Wu Yuxia are all virtuoso performers of the huqin (bowed string instruments including the erhu), pipa(a four-stringed lute) and liuqin (a plucked string instrument). American musicians have praised erhu performer Min Huifen as a genius. The French press also waxes lyrical about her playing, saying that even the pauses in her performance emit cadences. Wu Yuxia, pipa master and deputy head of China National Orchestra, has won awards both in China and abroad. She played the theme and incidental music for such films as The Last Emperor and Farewell My Concubine.

Inheritance and Progress

Performers of traditional Chinese music strive to innovate and improve their art through new performance techniques and by upgrading their instruments. Wang Huirans improvements to the liuqin have earned him the epithet “father of the liuqin.”

The liuqin or liuyeqin is so named for its resemblance to a willow leaf. (In Chinese, liu means willow). Originating in southern Shandong and northern Jiangsu provinces, it is the mainstay of musical ensembles that accompany local operas. The traditional liuqin has two strings, a range too narrow for smooth orchestral integration.

Wang Huiran first came upon the liuqin in 1958 during a trip to southern Shandong. He thereafter focused on improving the instrument. Working together with a musical instruments manufacturer in Xuzhou, Jiangsu Province, Wang produced the first three-string liuqin, which has sharper tones than the traditional model. He later added a fourth string, so giving the instrument a wider range. The upgraded liuqin thus has the characteristic features of the pipa, sanxian (a three-string fretless plucked instrument) guzheng (Chinese zither with movable bridges) and guitar, which makes it a very expressive instrument. Ideal for solos, it also constitutes the much-needed high-pitched plucked string instrument previously absent from national music orchestras. Chinas Ministry of Culture awarded Wang for this innovation. He has since composed many works for both liuqin solos and plucked string instrument ensembles.endprint

Artisans and manufacturers of national musical instruments, meanwhile, are advancing production methods of musical instruments – from materials to workmanship. Zhangs Musical Instruments is a private factory in Tianjin. Founder Zhang Fuqi started out making guqin (a seven-string plucked instrument) and huqin. He made several of the latter for huqin virtuoso Xu Lanyuan, who was especially favored by legendary Peking Opera master Mei Lanfang. Today, Zhangs business has expanded to include the manufacture of guzheng, erhu, pipa, flute, and ruan (a lute with a fretted neck, circular body and four strings). Some 10 veteran craftsmen from all over the country fashion these instruments out of diverse woods, such as sandalwood and black walnut. Zhang also set up a national musical instruments culture center that has run training programs for almost two decades.

Cultural Dividends

China Musical Instrument Association data show that in 2012, Chinas 28 large-scale traditional musical instrument manufacturing companies generated a total industrial output value of RMB 3.173 billion – 39.59 percent more than the previous year – and a total sales value of RMB 3.113 billion – an increase of 39.54 percent over 2011. Sales of the guzheng, the most popular instrument among novices, have soared. For example, more than 80,000 Dunhuang brand guzheng produced by Shanghai No. 1 National Music Instruments Factory were sold in 2013, generating a year-onyear growth of 27.4 percent and sales revenues in excess of RMB 200 million.

In recent years, governments at various levels have made consistent efforts to preserve and support Chinas folk music. Many projects involving national music appear successively on the four lists of national intangible cultural heritage items released by Chinas Ministry of Culture. They include the performance arts of guzheng and pipa, the manufacturing and performance skills of the flute of the Qiang ethnic group, the horse-head stringed instrument craftsmanship of the Mongolian ethnic group, and Shanghai manufacturing techniques of traditional musical instruments. There are still more items on local protection lists.

Market-oriented Innovations

In 2012 the Ministry of Culture named master guzheng maker Xu Zhengao of the Shanghai No. 1 National Music Instruments Factory an inheritor of national intangible cultural heritage.

Xu was born in 1933. He left his hometown for Shanghai while in his teens to make a living from producing plucked string instruments. He joined Shanghai No. 1 National Music Instruments Factory in 1958, and was apprenticed to senior guzheng maker Miao Jinlin. Xu worked so hard that he became qualified in just one year.endprint

At the end of 1963, Xu and Miao together developed a new type of guzheng that has a broader range and a more aesthetically pleasing form. As it later became the standard guzheng, Xu is known as the “father of guzheng.”

“After that, I started to design carved decorative patterns for the instrument,”Xu said. “It was hard at first. I tried to make dragon, tiger and shrimp designs, but none of them worked.” After practicing drawing every day he finally designed four carvings to embellish his guzheng, some of which are still applied today.

Xu often seeks the opinions of musicians when making a guzheng so that he can make innovations to suit perfor- mance needs. In 2001, Xu Zhengao, then in his late 60s, cooperated with prominent carver Zhong Yamin to make a sandalwood guzheng carved with cranes and turtles, which in Chinese culture symbolize longevity. This masterpiece won a national art award. Famous guzheng player Wang Zhongshan purchased the instrument for RMB 60,000.

Intent on passing on his guzhengmaking skills, Xu has taken on more than 100 apprentices. Today, his students are doing their utmost to develop this craftsmanship throughout the country. Xu, meanwhile, has been awarded a model worker of Shanghai and the nations senior craftsman. His dream has always been that the guzheng would“go global, as popular as the piano and violin.” But he is aware that even though exports of the guzheng are growing, the instrument is little known interna- tionally outside Chinese communities.“Guzheng can harmonize with many different instruments, and so have strong orchestral potential,” Xu said.

Head of the China National Orchestra Xi Qiang, in addition to the continuous improvement of instruments, calls for still more impressive compositions to preserve the artistic spirit of Chinese national music. Other than certain adapted classical works, many of todays compositions are newly created, and do not take the melodic preferences of folk music aficionados into consideration. “Compositions that appeal to both refined and popular tastes by virtue of their beautiful melodies and far-reaching artistic conceptions should become the mainstay of Chinese folk music,” Xi concluded. C endprint

endprint