脊柱畸形术后近端交界性后凸的研究现状

潘爱星 海涌 陈小龙 郭徽

青少年脊柱畸形矫形手术的目的是矫正畸形,而对于成人脊柱侧凸患者来讲,由于多合并有躯干的失平衡,重建脊柱平衡显得尤为重要[1],尤其以矢状面平衡重建的意义更为重要。近年来,随着后路矫形器械的发展和保留脊柱运动节段的需要,骨科医师越来越多地采取选择性后路节段性融合的手术策略,在取得良好临床疗效的同时[2],术后融合节段近端交界性后凸 ( proximal junctional kyphosis,PJK ) 和近端交界性失败 ( proximal junctional failure,PJF ) 的发生引起很多学者的重视。文献报道,PJK 占脊柱畸形术后并发症的 13%[3],长期随访发现因PJK 或 PJF 而进行翻修手术的发生率高达 9%[4]。因此,脊柱畸形矫形手术对患者矢状面平衡的恢复极其重要。但是目前对于脊柱畸形术后 PJK 的定义、发生机制、危险因素、预防措施及分类等仍未被广泛认识。笔者全面回顾目前关于脊柱畸形术后 PJK 或 PJF 相关文献,综述如下。

一、PJK 及 PJF 的定义

1994 年 Lowe 等[5]在对休门氏病 ( Scheuermann’s disease ) 后凸畸形患者的术后随访研究中首先详细描述了PJK。PJK 通常定义为术后近端交界区矢状面 Cobb’s 角>10° 或较术前增加 10°[6],也有文献定义为术后 Cobb’s 角大于或增加 15°[7]。Bridwell 等[8]认为交界区矢状面 Cobb’s角>20° 更能反映 PJK 的一些特征,提出应以此作为诊断标准。近端交界区后凸 Cobb’s 角为近端融合椎下终板与其近端第 2 个椎体的上终板之间的夹角[6-7,9-10]。这种测量方式可重复性很高,Sacramento-Dominguez 等[11]报道这种测量方法在同一个外科医生不同时间测量的一致性达 78%~92%,在不同医生之间的测量一致性为 55%~80%。近年 Kim 等[4]提出了 PJF 的概念,指伴有临床症状和近端交界区结构性失败的 PJK。PJK 是一个逐渐进展并加重的病理变化,如果后凸角度逐渐加大,将导致 PJF的发生[12]。PJF 不仅包括影像学上的后凸畸形,还包括近端交界区椎体或后方韧带复合体 ( posterior ligamentous complex,PLC ) 的结构性失败[13-15],同时可能伴有相应的临床症状。有研究表明交界区后凸 Cobb’s 角绝对值与患者背部疼痛和功能受限等临床症状严重程度直接相关[16]。其中,常见临床症状包括:( 1 ) 疼痛;( 2 ) 神经受压症状;( 3 ) 活动受限;( 4 ) 社会功能障碍;( 5 ) 不能目视前方[17]。

二、PJK 的发生率

脊柱畸形术后融合节段近端交界区发生一系列病理变化,包括邻近节段退变加速、PLC 破坏、椎体骨折、内固定失败、椎间盘退变以及小关节不稳等,最终导致交界区后凸形成。脊柱畸形术后 PJK 的发病率报道不同。Yagi等[15]对 157 例脊柱畸形术后患者进行平均 4.3 年的随访,20% ( 32 例 ) 的患者出现 PJK。但是在发生 PJK 组和未发生 PJK 组患者随访时脊柱侧凸研究学会 ( scoliosis research society,SRS ) 评分和 Oswestry 功能障碍指数 ( oswestry disability index,ODI ) 标准评分无明显差异。Kim 等[18]对249 例脊柱畸形矫形术后患者进行了平均 4 年的随访研究,17% 的患者出现 PJK。同样,在 Kim 的研究中,PJK对患者术后 SRS 评分没有产生明显影响。Maruo 等[19]对90 例行长节段融合的脊柱畸形矫形手术的患者进行了平均 2.9 年的随访研究,41% ( 37 例 ) 的患者出现 PJK。

纵观目前文献所报道的 PJK 发生率,从 5%~46% 不等[9,12,16,18-28]。但是大多数文献报道的发病率在 20%~40%之间[4,12,16,18-20,22-26]。

三、PJK 的发病机制

关于脊柱畸形术后发生 PJK 的机制有诸多不同理论。Peterson 等[29]认为脊柱后路坚强内固定使内固定两端应力增加,导致邻近节段椎间盘加速退变,引起交界性后凸形成。Kahn 等[30]认为脊柱侧凸的后路矫形手术破坏了脊柱后方的肌肉、韧带等软组织,从而导致小关节容易发生脱位和椎间隙的张开,最终将导致交界性后凸。Rhee 等[31]认为脊柱后路融合术后发生 PJK 的原因有:后方张力带的破坏;矫形过程近端加压对交界区的影响;矫形导致胸椎后凸减小,矢状面生理曲度的改变。

但是,脊柱畸形术后发生 PJK 是脊柱的自然退变病史还是手术相关因素导致的目前还不能确定。Glattes 等[6]为分析脊柱畸形术后发生 PJK 的原因,对 81 例行成人脊柱畸形患者术后作了 2 年以上随访研究,结果提示 PJK 的发生是手术还是患者因年龄增长的自然病史导致的还没有定论。

全面回顾相关文献,将脊柱畸形术后发生 PJK 近端交界区产生的病理变化总结如下:( 1 ) 年龄相关性后凸加重;( 2 ) PLC 断裂;( 3 ) 骨折;( 4 ) 内固定失败;( 5 ) 退变性椎间盘疾病;( 6 ) 小关节紊乱[3,18,31-32]。

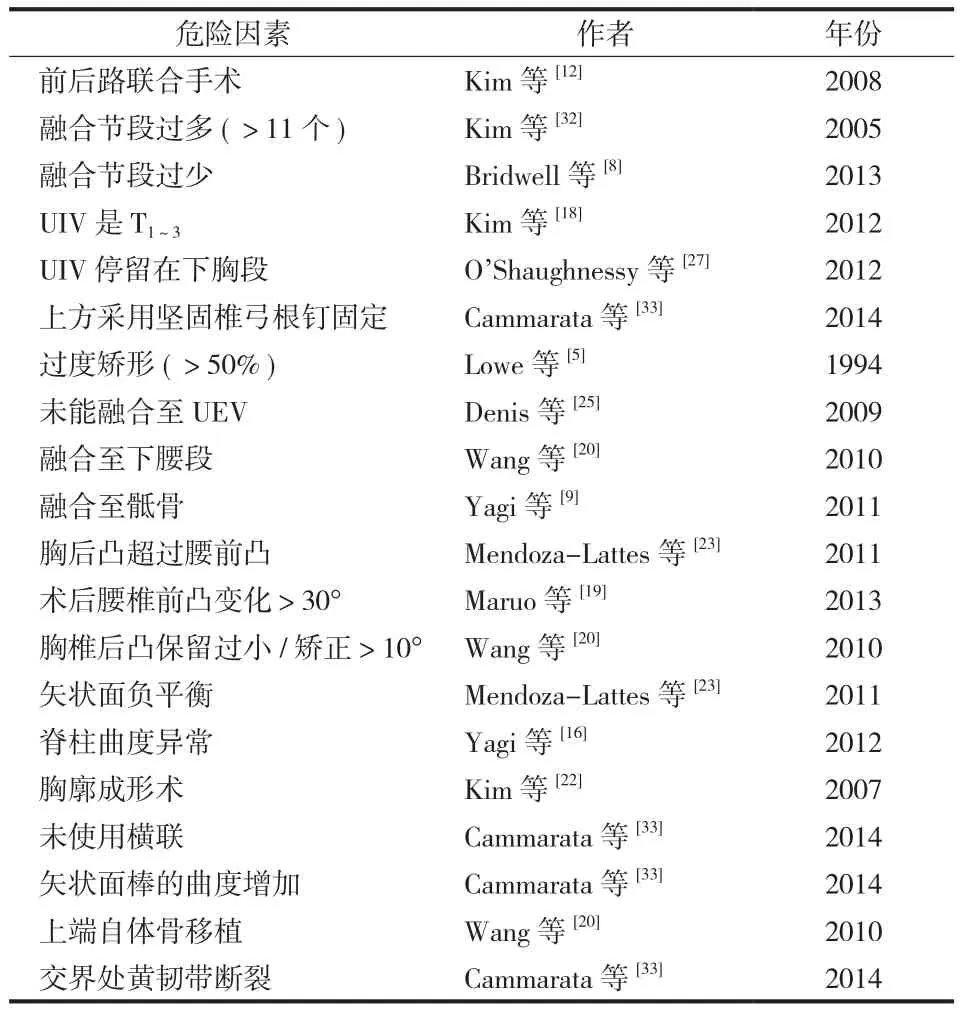

四、PJK 发生的危险因素

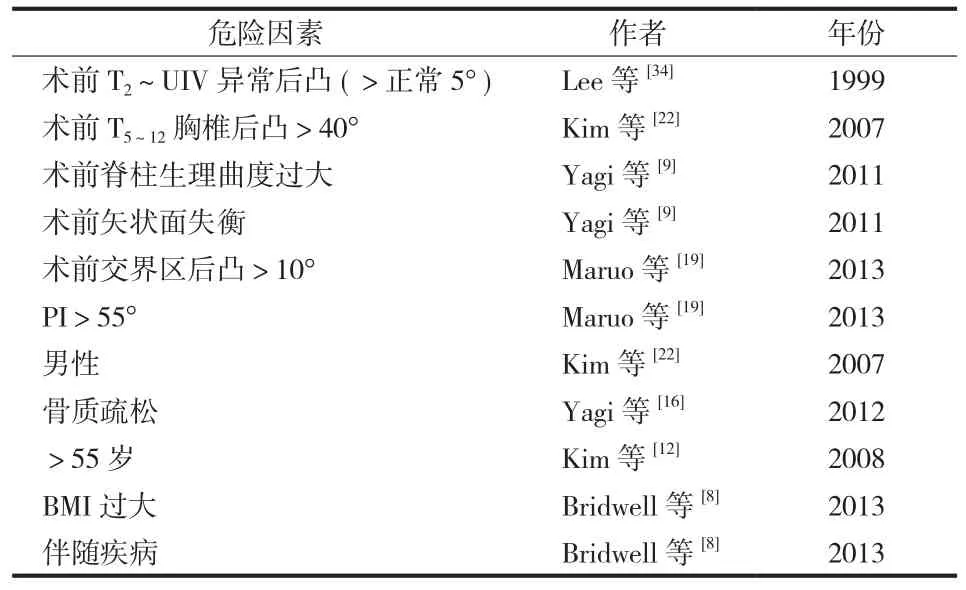

关于 PJK 发生的危险因素,相关研究报道不同。Kim等[12]报道年龄>55 岁和前后路联合手术是术后发生 PJK的明确危险因素。Maruo 等[19]对 90 例脊柱矫形术后患者进行平均 2.9 年的随访,37 例出现 PJK,作者认为术前胸椎前凸 ( thoracic kyphosis,TK ) Cobb’s 角>30°、术前交界区 Cobb’s 角>10°、术后腰椎前凸 ( lumbar lordosis,LL ) Cobb’s 角变化>30°、骨盆入射角 ( pelvic incidence,PI ) >55° 等脊柱矢状面参数异常是术后发生 PJK 的危险因素。Helgeson 等[7]、Cammarata 等[33]和 Kim 等[32]均认为椎弓根钉内固定和混合内固定是导致 PJK 发生的危险因素。Wang 等[20]对 123 例患者进行了平均 1.5 年的随访,35 例出现 PJK,作者认为术后 TK 减小 10° 以上、胸廓成形术、上固定椎使用椎弓根螺钉内固定、自体骨移植、融合至下腰椎是术后出现 PJK 的高危因素。此外,有文献报道,过大程度的矫形[8]、低骨量[16]、高体重指数[8,13]均能增加脊柱畸形术后 PJK 的发生率。

关于上固定椎停留的位置和融合节段的长短对术后发生 PJK 的影响仍存在争议。Kim 等[32]和 Bridwell 等[8]研究表明融合节段过长和过短都是术后发生 PJK 的危险因素。上固定椎停留在上胸段或下胸段都被认为是导致 PJK的因素之一[8,18,25]。如果融合至上胸椎,术后发生 PJK 的原因一般是由韧带等软组织失败引起;而融合节段停留在下胸段术后发生 PJK 多是继发于邻近椎体骨折[1,19]。

总结归纳目前文献中所报道的脊柱畸形术后发生 PJK的危险因素,按可控制和不可控制分为两类,归纳为表 1和表 2。

五、PJK 的预防

1. 骨水泥强化:近年来,在脊柱畸形矫形手术中,在近端交界区椎体使用骨水泥强化预防 PJK 得到越来越多的应用。骨水泥强化后可在一定程度上避免内固定失败和邻近椎体的骨折,避免 PJK 或 PJF 的发生。Hart 等[15]对28 例老年女性患者行脊柱长节段固定术后进行观察,其中 15 例进行了预防性骨水泥强化处理,13 例未行强化。术后未强化组患者中 2 例出现了 PJK,强化组没有 PJK 发生,在一定程度上降低了 PJK 的发生率。

Kayanja 等[35]和 Kebaish 等[36]对使用骨水泥强化预防 PJK 进行了相关的生物力学研究。Kebaish 对 18 例脊柱标本进行了生物力学测试,所有标本均使用椎弓根螺钉从T10~L5进行融合。分别对上固定椎、上固定椎+近端邻近椎体进行骨水泥强化。在脊柱标本垂直受压情况下,对照组 ( 无骨水泥强化 ) 83% 出现了椎体骨折,上固定椎强化组 100% 出现椎体骨折,而上固定椎+近端邻近椎体进行骨水泥强化组仅 17% 发生椎体骨折。Kayanja 等对骨水泥强化节段数进行了生物力学分析。分别对骨水泥强化节段数 ( 0、1、2、3、4、5 ) 进行生物力学性能对比。结果显示脊柱的刚度与骨水泥强化的节段数量无关,而与椎体的骨密度有关。作者建议在脊柱多节段融合术后为了预防交界区发生后凸或失败,应在凡是有骨折风险的椎体进行骨水泥强化,而不是针对交界区的椎体。

表1 脊柱畸形术后发生 PJK 的可控危险因素Tab.1 Modifiable risk factors of PJK after spine deformity surgery

表2 脊柱畸形术后发生 PJK 的不可控危险因素Tab.2 Non-modifiable risk factors of PJK after spine deformity surgery

当然使用骨水泥强化预防 PJK 的发生也有许多缺点。例如,骨水泥阻断了椎体内血供,减少了椎间盘的营养供给[37],加速椎间盘的退变;而且骨水泥的注入使脊柱的力学传导发生改变,增加了邻近椎体骨折的风险[14]。

2. 椎板钩的应用:椎弓根螺钉内固定系统提供了脊柱三柱结构的坚强固定,但同时也增加了邻近椎体的受力,加速了小关节及椎间盘的退变,导致 PJK 的发生[7,22,32]。Helgeson 等[7]对 283 例青少年特发性脊柱侧凸( adolescent idiopathic scoliosis,AIS ) 患者术后进行了 2 年随访,根据内固定方式不同分为 4 组:A 组椎板钩固定( 51 例 ),B 组混合固定方式 ( 177 例 ),C 组椎弓根螺钉固定 ( 37 例 ),D 组仅在上固定椎使用椎板钩固定 ( 18 例 )。末次随访时 PJK 发生率 A 组为 0%,B 组为 2.3%,C 组为8.1%,D 组为 5.6%。结果提示椎板钩固定可有效降低 PJK的发生。同样的结论在 Hassanzadeh 等[38]的研究中得到了验证。作者回顾了 41 例脊柱多节段融合术后 PJK 的发生情况,其中上固定椎使用椎弓根钉固定的患者术后 2 年有29.6% 出现 PJK,而上固定椎采用椎板钩固定的患者没有1 例发生 PJK。

由此可见,椎板钩固定的应用可以有效地预防脊柱多节段融合术后出现 PJK。尤其是在近端固定椎使用椎板钩可以提供一个非坚强的固定结构,有利于保护邻近节段小关节和椎间盘退变,预防交界区应力过于集中,导致 PJK或 PJF 的发生。

3. 生长棒的应用:儿童脊柱侧凸在发病初期常常使用垂直可调节生长棒技术控制脊柱侧凸发展。有少数研究表明生长棒技术可降低脊柱畸形术后 PJK 的发生率。Li等[39]对 68 例儿童脊柱侧凸行生长棒调节患者术后进行1 年随访,发现 PJK 的发生率仅 6%,明显低于平均发病率 ( 20%~40% )。但是 Li 等定义的 PJK 标准为交界区Cobb’s 角术后增加 25°。因此其真实 PJK 发病率不得而知。在 Thompson 等[40]的研究中,儿童脊柱侧凸生长棒调节术后,22% 的患者出现 PJK;同样,在 Hasler 等[41]生长棒技术研究中,PJK 的发生率为 38%,与椎弓根螺钉内固定技术的术后 PJK 发生率相当。

因此,生长棒技术能否有效预防脊柱畸形术后 PJK 的发生仍需要更多的研究进行证实。

六、PJK 的评估和治疗

关于 PJK 的严重程度评估目前还没有统一的标准。脊柱畸形术后发生 PJK 何时进行干预?何时需要进行翻修手术?目前还没有定论。Yagi 等[9]在 2011 年提出关于 PJK的分类和分级标准。此标准根据 PJK 发生的病因和局部后凸程度将其分为 3 类和 3 级 ( 表 3 )。Yagi 提出的 PJK 标准很简化,方便临床医生应用。缺点是此标准并未对患者临床症状进行评估,对于哪些患者需要进行手术干预,Yagi标准没有给出明确答案。

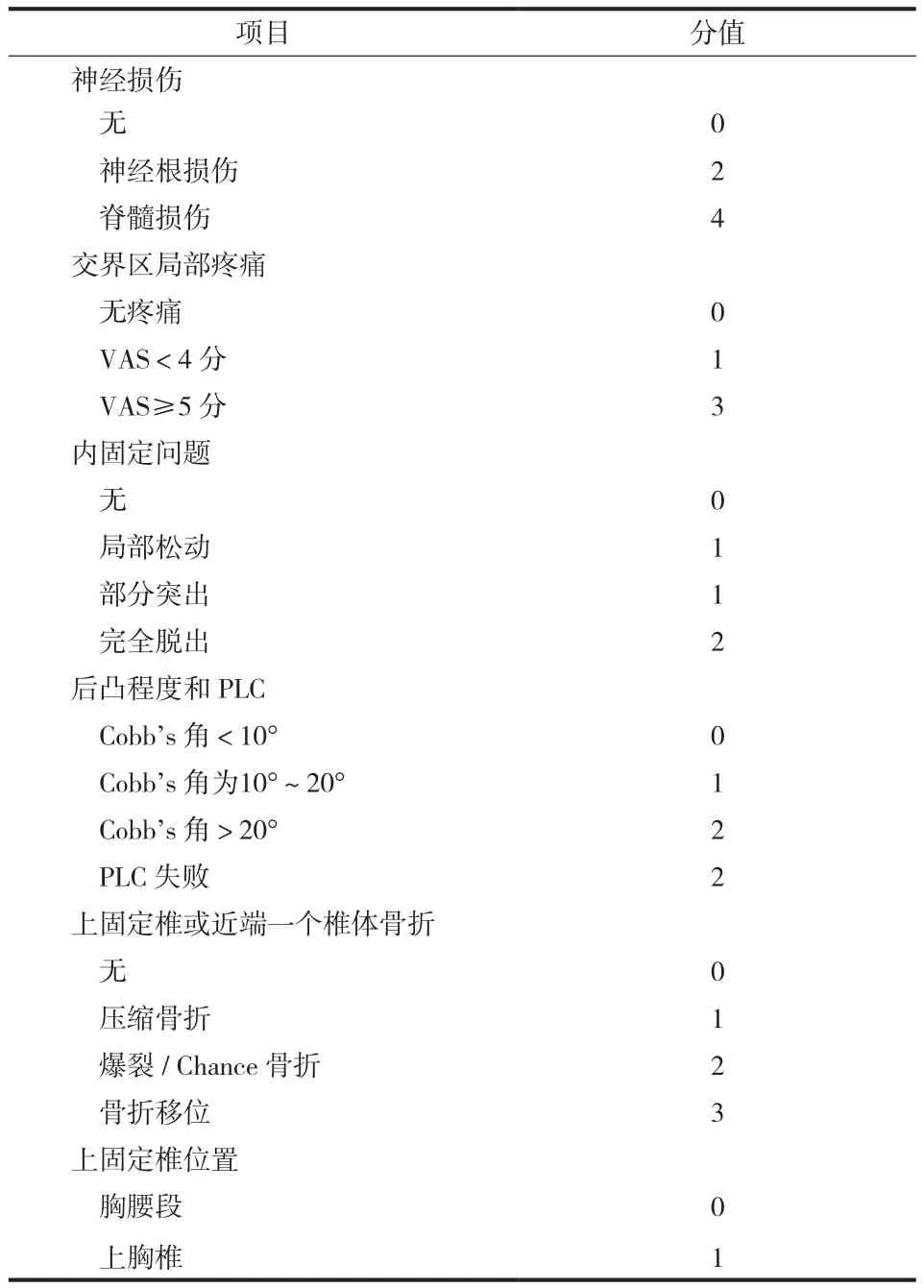

为了明确翻修手术的适应证,Hart 等[42]和国际脊柱研究学会 ( international spine study group,ISSG ) 在 2013 年提出了评价 PJK 严重程度的评分标准 ( 表 4 )。该评分标准包括神经损伤、局部疼痛、内固定问题、交界区后凸程度、交界区骨折情况及上固定椎位置 6 个方面的内容。每一方面根据其特点和严重程度定义为不同分值,6 项总得分为 Hart-ISSG 严重程度评分。当评分达到 7 分时建议行手术干预治疗。Hart-ISSG 严重程度评分标准较为全面地评估 PJK 的进展和对患者功能的影响,为临床评估和治疗提供了有效的参考。

表3 Yagi M- PJK 标准Tab.3 Classifications of PJK put forward by Yagi-M

表4 Hart-ISSG PJK 严重程度评分表Tab.4 Hart-International Spine Study Group PJK severity scale

七、总结

脊柱畸形术后融合节段 PJK 和 PJF 应引起高度重视。脊柱畸形术后发生 PJK 是脊柱的自然退变病史,还是手术相关因素导致的,目前还没有定论。全面认识 PJK 发生的危险因素,合理选择融合节段、手术中保护 PLC 结构、恢复脊柱正常生理曲度、保持躯干平衡以及避免内固定失败等,是减少 PJK 发生的有效措施。面对 PJK 或 PJF,应全面地进行标准化的临床评估,选择正确的治疗措施。

[1] Hostin R, McCarthy I, OʼBrien M, et al. Incidence, mode, and location of acute proximal junctional failures after surgical treatment of adult spinal deformity. Spine, 2013, 38(12):1008-1015.

[2] 普有登, 段洪, 周兆文, 等. 后路选择性减压固定融合治疗退行性脊柱侧凸. 中国骨与关节杂志, 2014, 3(1):15-19.

[3] Smith JS, Sansur CA, Donaldson WF 3rd, et al. Shortterm morbidity and mortality associated with correction of thoracolumbar fixed sagittal plane deformity: a report from the Scoliosis Research Society Morbidity and Mortality Committee. Spine, 2011, 36(12):958-964.

[4] Kim HJ, Lenke LG, Shaffrey CI, et al. Proximal junctional kyphosis as a distinct form of adjacent segment pathology after spinal deformity surgery: a systematic review. Spine, 2012,37(Suppl 22):S144-164.

[5] Lowe TG, Kasten MD. An analysis of sagittal curves and balance after Cotrel-Dubousset instrumentation for kyphosis secondary to Scheuermann’s disease. A review of 32 patients.Spine, 1994, 19(15):1680-1685.

[6] Glattes RC, Bridwell KH, Lenke LG, et al. Proximal junctional kyphosis in adult spinal deformity following long instrumented posterior spinal fusion: incidence, outcomes, and risk factor analysis. Spine, 2005, 30(14):1643-1649.

[7] Helgeson MD, Shah SA, Newton PO, et al. Evaluation of proximal junctional kyphosis in adolescent idiopathic scoliosis following pedicle screw, hook, or hybrid instrumentation.Spine, 2010, 35(2):177-181.

[8] Bridwell KH, Lenke LG, Cho SK, et al. Proximal junctional kyphosis in primary adult deformity surgery: evaluation of 20 degrees as a critical angle. Neurosurgery, 2013, 72(6):899-906.

[9] Yagi M, Akilah KB, Boachie-Adjei O. Incidence, risk factors and classification of proximal junctional kyphosis: surgical outcomes review of adult idiopathic scoliosis. Spine, 2011,36(1):E60-68.

[10] Hart R, McCarthy I, O’Brien M, et al. Identification of decision criteria for revision surgery among patients with proximal junctional failure after surgical treatment of spinal deformity.Spine, 2013, 38(19):E1223-1227.

[11] Sacramento-Dominguez C, Vayas-Diez R, Coll-Mesa L, et al.Reproducibility measuring the angle of proximal junctional kyphosis using the first or the second vertebra above the upper instrumented vertebrae in patients surgically treated for scoliosis. Spine, 2009, 34(25):2787-2791.

[12] Kim YJ, Bridwell KH, Lenke LG, et al. Proximal junctional kyphosis in adult spinal deformity after segmental posterior spinal instrumentation and fusion: minimum five-year followup. Spine, 2008, 33(20):2179-2184.

[13] O’Leary PT, Bridwell KH, Lenke LG, et al. Risk factors and outcomes for catastrophic failures at the top of long pedicle screw constructs: a matched cohort analysis performed at a single center. Spine, 2009, 34(20):2134-2139.

[14] Watanabe K, Lenke LG, Bridwell KH, et al. Proximal junctional vertebral fracture in adults after spinal deformity surgery using pedicle screw constructs: analysis of morphological features.Spine, 2010, 35(2):138-145.

[15] Hart RA, Prendergast MA, Roberts WG, et al. Proximal junctional acute collapse cranial to multi-level lumbar fusion:a cost analysis of prophylactic vertebral augmentation. Spine J,2008, 8(6):875-881.

[16] Yagi M, King AB, Boachie-Adjei O. Incidence, risk factors,and natural course of proximal junctional kyphosis: surgical outcomes review of adult idiopathic scoliosis. Minimum 5 years of follow-up. Spine, 2012, 37(17):1479-1489.

[17] McClendon J Jr, O’Shaughnessy BA, Sugrue PA, et al.Techniques for operative correction of proximal junctional kyphosis of the upper thoracic spine. Spine, 2012, 37(4):292-303.

[18] Kim HJ, Yagi M, Nyugen J, et al. Combined anterior-posterior surgery is the most important risk factor for developing proximal junctional kyphosis in idiopathic scoliosis. Clin Orthop Relat Res, 2012, 470(6):1633-1639.

[19] Maruo K, Ha Y, Inoue S, et al. Predictive factors for proximal junctional kyphosis in long fusions to the sacrum in adult spinal deformity. Spine, 2013, 38(23):E1469-1476.

[20] Wang J, Zhao Y, Shen B, et al. Risk factor analysis of proximal junctional kyphosis after posterior fusion in patients with idiopathic scoliosis. Injury, 2010, 41(4):415-420.

[21] Kim HJ, Bridwell KH, Lenke LG, et al. Proximal junctional kyphosis results in inferior SRS pain subscores in adult deformity patients. Spine, 2013, 38(11):896-901.

[22] Kim YJ, Lenke LG, Bridwell KH, et al. Proximal junctional kyphosis in adolescent idiopathic scoliosis after 3 different types of posterior segmental spinal instrumentation and fusions:incidence and risk factor analysis of 410 cases. Spine, 2007,32(24):2731-2738.

[23] Mendoza-Lattes S, Ries Z, Gao Y, et al. Proximal junctional kyphosis in adult reconstructive spine surgery results from incomplete restoration of the lumbar lordosis relative to the magnitude of the thoracic kyphosis. Iowa Orthop J, 2011,31:199-206.

[24] Ha Y, Maruo K, Racine L, et al. Proximal junctional kyphosis and clinical outcomes in adult spinal deformity surgery with fusion from the thoracic spine to the sacrum: a comparison of proximal and distal upper instrumented vertebrae. J Neurosurg Spine, 2013, 19(3):360-369.

[25] Denis F, Sun EC, Winter RB. Incidence and risk factors for proximal and distal junctional kyphosis following surgical treatment for Scheuermann kyphosis: minimum five-year follow-up. Spine, 2009, 34(20):E729-734.

[26] Hyun SJ, Rhim SC. Clinical outcomes and complications after pedicle subtraction osteotomy for fixed sagittal imbalance patients : a long-term follow-up data. J Korean Neurosurg Soc,2010, 47(2):95-101.

[27] O’Shaughnessy BA, Bridwell KH, Lenke LG, et al. Does a long-fusion “T3-sacrum” portend a worse outcome than a shortfusion “T10-sacrum” in primary surgery for adult scoliosis?Spine, 2012, 37(10):884-890.

[28] Kim HJ, Bridwell KH, Lenke LG, et al. Patients with proximal junctional kyphosis requiring revision surgery have higher postoperative lumbar lordosis and larger sagittal balance corrections. Spine, 2014, 39(9):E576-580.

[29] Peterson HA. The Pediatric Spine: Principle and Practice.Weinstein SL: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, 1994:651-654.

[30] Kahn E, Brown JC, Swank SM. Postoperative thoracic kyphosis following Luque instrumentation. Orthop Trans, 1987,11:88.

[31] Rhee JM, Bridwell KH, Won DS, et al. Sagittal plane analysis of adolescent idiopathic scoliosis: the effect of anterior versus posterior instrumentation. Spine, 2002, 27(21):2350-2356.

[32] Kim YJ, Bridwell KH, Lenke LG, et al. Proximal junctional kyphosis in adolescent idiopathic scoliosis following segmental posterior spinal instrumentation and fusion: minimum 5-year follow-up. Spine, 2005, 30(18):2045-2050.

[33] Cammarata M, Aubin CE, Wang X, et al. Biomechanical risk factors for proximal junctional kyphosis: a detailed numerical analysis of surgical instrumentation variables. Spine, 2014,39(8):E500-507.

[34] Lee GA, Betz RR, Clements DH 3rd, et al. Proximal kyphosis after posterior spinal fusion in patients with idiopathic scoliosis.Spine, 1999, 24(8):795-799.

[35] Kayanja MM, Schlenk R, Togawa D, et al. The biomechanics of 1, 2, and 3 levels of vertebral augmentation with polymethylmethacrylate in multilevel spinal segments. Spine,2006, 31(7):769-774.

[36] Kebaish KM, Martin CT, O’Brien JR, et al. Use of vertebroplasty to prevent proximal junctional fractures in adult deformity surgery: a biomechanical cadaveric study. Spine J,2013, 13(12):1897-1903.

[37] Verlaan JJ, Oner FC, Slootweg PJ, et al. Histologic changes after vertebroplasty. The Journal of bone and joint surgery.J Bone Joint Surg Am, 2004, 86-A(6):1230-1238.

[38] Hassanzadeh HGS, Jain A, El Dafrawy MH, et al. Type of anchor at the proximal fusion level has a significant effect on the incidence of proximal junctional kyphosis and outcome in adults after long posterior spinal fusion. Spine Deformity, 2013,1(4):299-305.

[39] Li YGM, Karlin L. Proximal junctional kyphosis after vertical expandable prosthetic titanium rib insertion. Spine Deformity,2013, 1(6):425-433.

[40] Thompson GH, Akbarnia BA, Campbell RM Jr. Growing rod techniques in early-onset scoliosis. J Pediatr Orthop, 2007,27(3):354-361.

[41] Hasler CC, Mehrkens A, Hefti F. Efficacy and safety of VEPTR instrumentation for progressive spine deformities in young children without rib fusions. Eur Spine J, 2010, 19(3):400-408.

[42] Hart RBS, Burton DC, Shaffrey CI, et al. Proximal Junctional Failure (PJF) Classification and Severity Scale: Development and Validation of a Standardized System. 2013 Annual Meeting of the AANS/CNS Section on Disorders of the Spine and Peripheral Nerves. Phoenix, Arizona, 2013.