外源性硫化氢及KATP通道对大鼠慢性应激结肠高动力的调节*

刘 颖, 全晓静, 夏 虹, 罗和生

(1桂林医学院附属医院消化科,广西 桂林 541001; 2武汉大学人民医院消化科,湖北 武汉 430060)

外源性硫化氢及KATP通道对大鼠慢性应激结肠高动力的调节*

刘 颖1△, 全晓静2, 夏 虹2, 罗和生2

(1桂林医学院附属医院消化科,广西 桂林 541001;2武汉大学人民医院消化科,湖北 武汉 430060)

目的: 研究外源性硫化氢(hydrogen sulfide,H2S)及ATP敏感性钾通道(ATP-sensitive potassium channels,KATP)在慢性应激结肠高动力中的作用。方法: 制作慢性避水应激(water avoidance stress,WAS) 和假避水应激(sham water avoidance stress,SWAS)大鼠模型,观察2组大鼠结肠肌条的收缩活性以及硫氢化钠(NaHS)和格列本脲预处理后对2组大鼠结肠肌条收缩影响并计算NaHS的半数抑制浓度(half maximal inhibitory concentration,IC50),使用免疫荧光及Western blotting法观察KATP通道各亚基在结肠中的分布及表达。结果: WAS组结肠肌条收缩活性明显高于SWAS组;NaHS浓度依赖性抑制2组大鼠纵行肌 (longitudinal muscle,LM)和环形肌(circular muscle,CM)的收缩;WAS组LM和CM的NaHS IC50分别为0.2033 mmol/L和0.1438 mmol/L,均明显低于SWAS组(P<0.01);格列本脲明显增加2组大鼠肌条NaHS IC50(P<0.01);Kir6.1、Kir6.2和SUR-2B在2组大鼠结肠固有肌细胞膜均有分布;WAS组(去除黏膜及黏膜下层后)Kir6.1和SUR2B蛋白表达高于SWAS组(P<0.01)。结论: H2S外源性供体NaHS对慢性应激结肠高动力具有潜在的治疗作用。KATP通道亚基Kir6.1/SUR2B表达增加可能是慢性应激结肠动力紊乱的一种适应性反应。

慢性应激; 高动力; 硫化氢; ATP敏感性钾通道

慢性应激可导致结肠动力增加[1-4],从而诱发或加剧IBS和IBD胃肠道症状等[2, 5-6]。已证实硫化氢(H2S)对胃肠动力具有重要的调节作用,主要表现为抑制肠道动力[7-9],H2S抑制机制主要与直接开放位于平滑肌细胞上的ATP敏感性钾通道 (ATP-sensitive potassium channels,KATP)有关[8, 10-14]。我们的前期研究发现慢性避水应激(water avoidance stress,WAS)大鼠结肠动力增加,而结肠局部内源性H2S合成酶表达下调、H2S产生减少可能是其动力增加的原因之一[15]。但作为H2S的靶通道亦是与消化道平滑肌兴奋性密切相关的通道,KATP通道的数量及功能在慢性WAS结肠动力紊乱时变化如何仍不清楚;H2S外源性供体硫氢化钠(NaHS)是否对WAS结肠高动力具有潜在治疗作用以及该作用是否通过KATP通道来介导亦不明了。本研究通过观察慢性应激时结肠平滑肌KATP通道各亚基分布表达变化以及H2S外源性供体NaHS对结肠高动力的影响,以探讨KATP通道在慢性应激结肠动力紊乱中的作用以及NaHS对其潜在的治疗价值。

材 料 和 方 法

1 动物、试剂与仪器

健康雄性Wistar大鼠,SPF级,体重180~220 g,购自湖北省疾病预防控制中心,动物许可证号:SCXK(鄂) 2008-0005。动物用混合配方饲料喂养,自由进食饮水,定期更换垫料,保持大鼠生活环境通风和清洁卫生。

NaHS及格列苯脲均购自Sigma;羊抗大鼠Kir6.1、Kir6.2和SUR2B多克隆抗体均购自Santa Cruz;羊抗大鼠GAPDH多克隆抗体、辣根过氧化物酶标记兔抗羊IgG、Cy3标记兔抗羊IgG、二甲基亚砜(dimethyl sulfoxide,DSMO)和DAB显色剂均购自北京中山生物技术有限公司;SDS-PAGE凝胶配制试剂盒、Western blotting转膜液、封闭液、硝酸纤维膜和Bradford蛋白浓度测定试剂盒均购自博士德公司。台式液成分为(mmol/L):氯化钠 147.0, 氯化钾 4.0, 氯化钙 2.0, 磷酸二氢钠 0.42, 磷酸氢二钠 2.0, 氯化镁 1.05, 葡萄糖 5.5,以氢氧化钠调pH值至7.4。

解剖显微镜、荧光显微镜(Olympus);张力换能器、RM6240多通道生理信号采集处理系统(成都仪器厂);AB-104 电子天平(Mettler Toledo);低温离心机(Thermo Electron);电泳仪(Bio-Rad)。

2 方法

2.1 大鼠分组及慢性避水应激模型的制作 大鼠随机分为慢性WAS组(n=10)和假避水应激(sham water avoidance stress,SWAS)组(n=10)。WAS大鼠模型是国内外普遍认可并用于研究慢性应激结肠高动力相关机制的模型[1, 6],模型制作方法按照文献报道[1-2]进行:大鼠放于周边有水的8 cm×6 cm×6 cm的平台上(水低于平台1 cm);SWAS组大鼠放于周围无水的平台。2组大鼠均观察1 h,每天1次,连续10 d,每日固定在8:00~13:00进行实验。

2.2 结肠平滑肌条的制备及其自发性收缩的记录 击昏大鼠后颈动脉放血处死,剖腹,在距回盲瓣1 cm处取约3 cm长的结肠,置入通有95% O2和5% CO2混合气体的台氏液中,沿肠系膜处剪开肠管并漂洗干净,黏膜面朝上并固定于硅胶板上,解剖显微镜下迅速剥离黏膜和黏膜下层,沿肠管纵轴走向剪取纵行肌条(longitudinal muscle,LM),沿横轴走向剪取环形肌条(circular muscle,CM)。将肌条放置于盛有恒温(37 ℃)台式液的浴槽中(容积约6 mL),并持续充有95% O2和5% CO2的混合气体,肌条的一端固定在浴槽底部挂钩,另一端用丝线固定于张力换能器上。给肌条1.0 g前负荷,孵育1 h,台式液每隔15 min予以更换。每只大鼠选取出现规律收缩的LM和CM各 1 根记录机械收缩信号,收缩强度以曲线下面积(area under the curve,AUC)表示。待结肠平滑肌条出现规律收缩后分别以累计加药法加入不同浓度(0.01~1 mmol/L)的NaHS溶液,观察肌条曲线下面积的变化;以格列苯脲(10 μmol/L)孵育肌条30 min后,再以累计加药法加入不同浓度(0.01~1 mmol/L)的NaHS溶液,观察肌条曲线下面积的变化,结果以肌条收缩AUC抑制率表示 [AUC抑制率(%)=(给药前-给药后)/给药前×100%]。

2.3 免疫荧光染色检测结肠SUR-2B、Kir6.1和Kir6.2的分布 取结肠标本约1 cm,10%中性缓冲福尔马林固定约24 h;冲洗后常规脱水、透明、浸蜡、包埋,石蜡包埋切片厚约5 μm;切片脱蜡至水并行抗原修复后,滴加3%牛封闭血清37 ℃湿盒中封闭1 h;分别加入 I 抗(SUR-2B 1∶250,Kir6.1 1∶300,Kir6.2 1∶300),4 ℃湿盒中孵育过夜;PBS冲洗后,Cy3标记兔抗羊IgG (1∶100),37 ℃湿盒中避光孵育1 h;PBS冲洗后,甘油封片,荧光显微镜下观察。

2.4 Western blotting检测结肠(去除黏膜及黏膜下层)SUR-2B、Kir6.1和Kir6.2的表达 取大鼠近端结肠组织(去除黏膜及黏膜下层)约1 g,经RIPA裂解液裂解后,匀浆液经离心后上清分装放入-80 ℃冰箱保存;使用BCA蛋白浓度测定试剂盒、紫外分光光度计测定蛋白浓度。取50 μg总蛋白进行聚丙烯酰胺凝胶(SDS-PAGE,10%分离胶)电泳,将电泳后的蛋白质电转移至PVDF膜上,用5%脱脂奶粉摇床室温封闭2 h,洗脱后分别加入 I 抗(SUR-2B 1∶400,Kir6.1 1∶400,Kir6.2 1∶400,GAPDH 1∶200)、4 ℃过夜,经PBST 冲洗后以碱性磷酸酶标记的 II抗(1∶10 000)室温摇床孵育2 h;经TBST洗涤后滴加适量的ECL底物液,孵育数分钟;待荧光带明显后,覆上保鲜膜,X光胶片压片后行显影、定影。使用BandScan分析胶片灰度值,将各组SUR-2B、Kir6.1和Kir6.2灰度值分别与GAPDH灰度值的比值作为相对表达量,统计分析各组表达量差异。

3 统计学处理

用GraghPad Prism 5.0软件分析处理,数据以均数±标准差(mean±SD)表示,组间比较行两独立样本t检验;进行曲线拟合并计算半数抑制浓度(half maximal inhibitory concentration,IC50),单位换算成mmol/L;以P<0.05为差异有统计学意义。

结 果

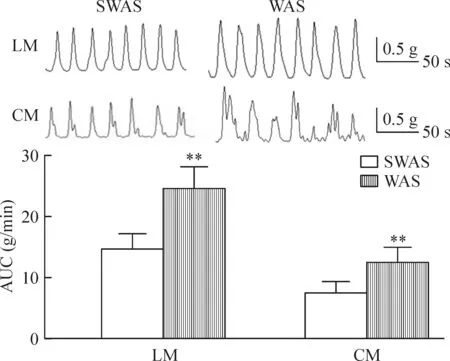

1 WAS大鼠结肠肌条收缩活性明显增高

WAS组大鼠LM 和CM的AUC均高于SWAS 组 [LM:(23.59±3.23) g/minvs(14.38±2.56) g/min;CM:(12.62±2.13) g/minvs(7.97±1.94) g/min, 均P<0.01),见图1。

Figure 1.WAS increased contractile activity of colonic strips. Mean ± SD.n=10.**P< 0.01vsSWAS group.

图1 WAS增加大鼠结肠肌条收缩活性

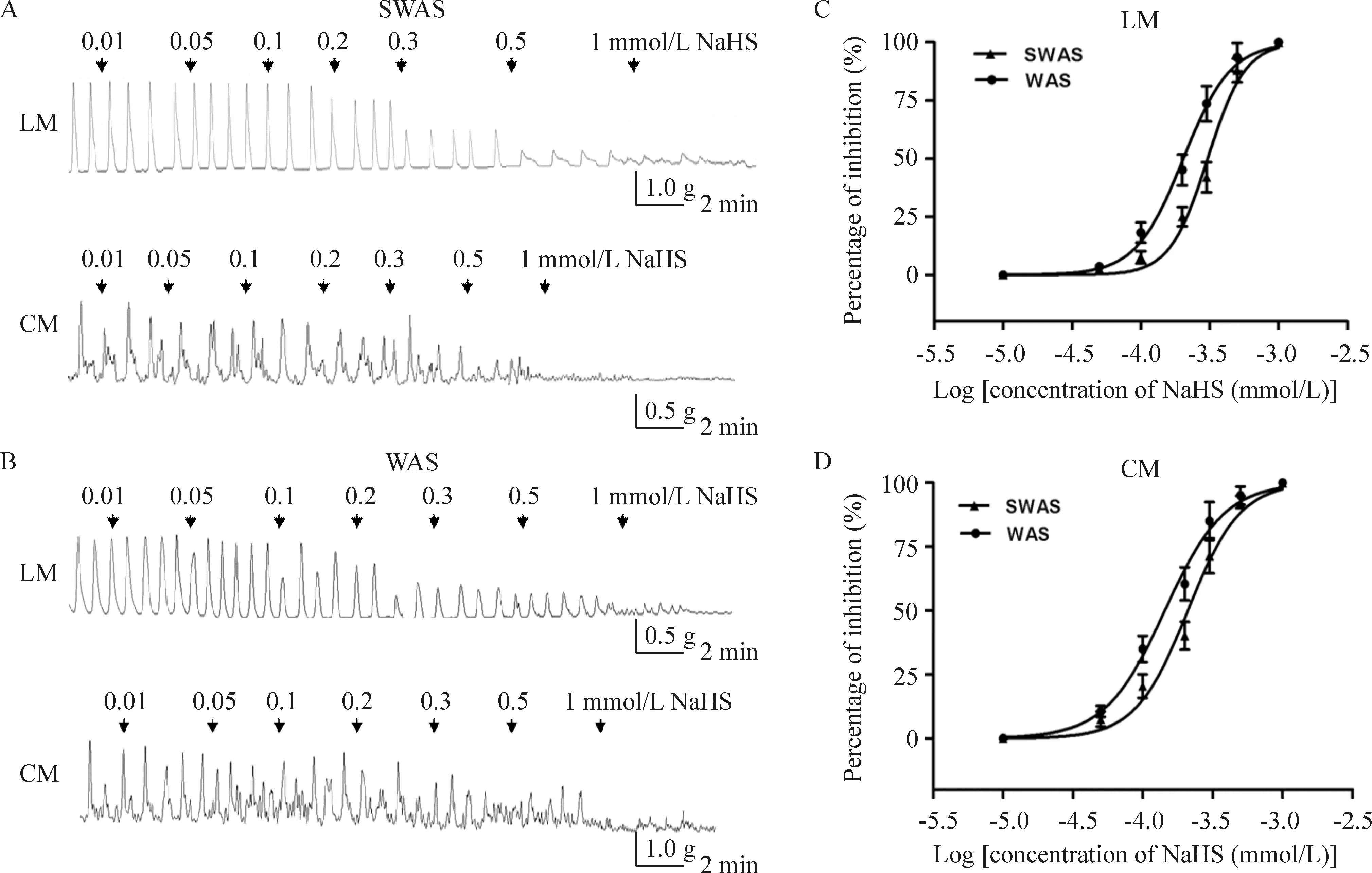

2 外源性NaHS抑制大鼠结肠平滑肌条自发性收缩

NaHS(0.01~1 mmol/L)对SWAS和WAS大鼠的LM和CM自发性收缩均产生浓度依赖性抑制效应, NaHS为 1 mmol/L时产生100%抑制。WAS大鼠LM的NaHS IC50为0.203 mmol/L(95%可信区间 IC500.187~0.221, logIC50=-3.692±0.015), 明显低于SWAS组(IC50=0.305 mmol/L, 95%可信区间IC500.271~0.345, logIC50=-3.515±0.020,P<0.01)。WAS大鼠CM的 NaHS IC50为0.144 mmol/L(95%可信区间 IC500.127~0.162, logIC50=-3.842±0.021),亦明显低于SWAS组(IC50=0.210 mmol/L, 95% 可信区间 IC500.181~0.244,logIC50=-3.678±0.025,P<0.01),见图2。

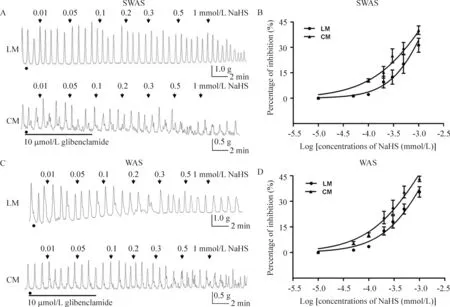

3 KATP通道阻断剂减弱NaHS的抑制作用

KATP通道阻断剂格列本脲明显减低NaHS的抑制作用。加入格列本脲(10 μmol/L)孵育肌条30 min后,NaHS(1 mmol/L)的抑制效应仅达原来的30%~45%。SWAS组,格列本脲增加LM的NaHS IC50,NaHS IC50从0.305 mmol/L增加至2.102 mmol/L(95%可信区间IC50为 1.622~2.725,logIC50=-2.677±0.044,P<0.01); 格列本脲亦增加CM的NaHS IC50,NaHS IC50从0.210 mmol/L增加至1.484 mmol/L(95% 可信区间IC50为0.991~2.224,logIC50=-2.828±0.068,P<0.01)。WAS组, 格列本脲增加LM的NaHS的IC50,NaHS IC50从0.203 mmol/L增加至1.756 mmol/L(95% 可信区间 IC501.235~2.496,logIC50=-2.756±0.059,P<0.01); 格列本脲亦增加CM的NaHS IC50,NaHS IC50从0.144增加至1.231 mmol/L(95%可信区间IC500.900~1.682,logIC50=-2.910±0.053,P<0.01),见图3。

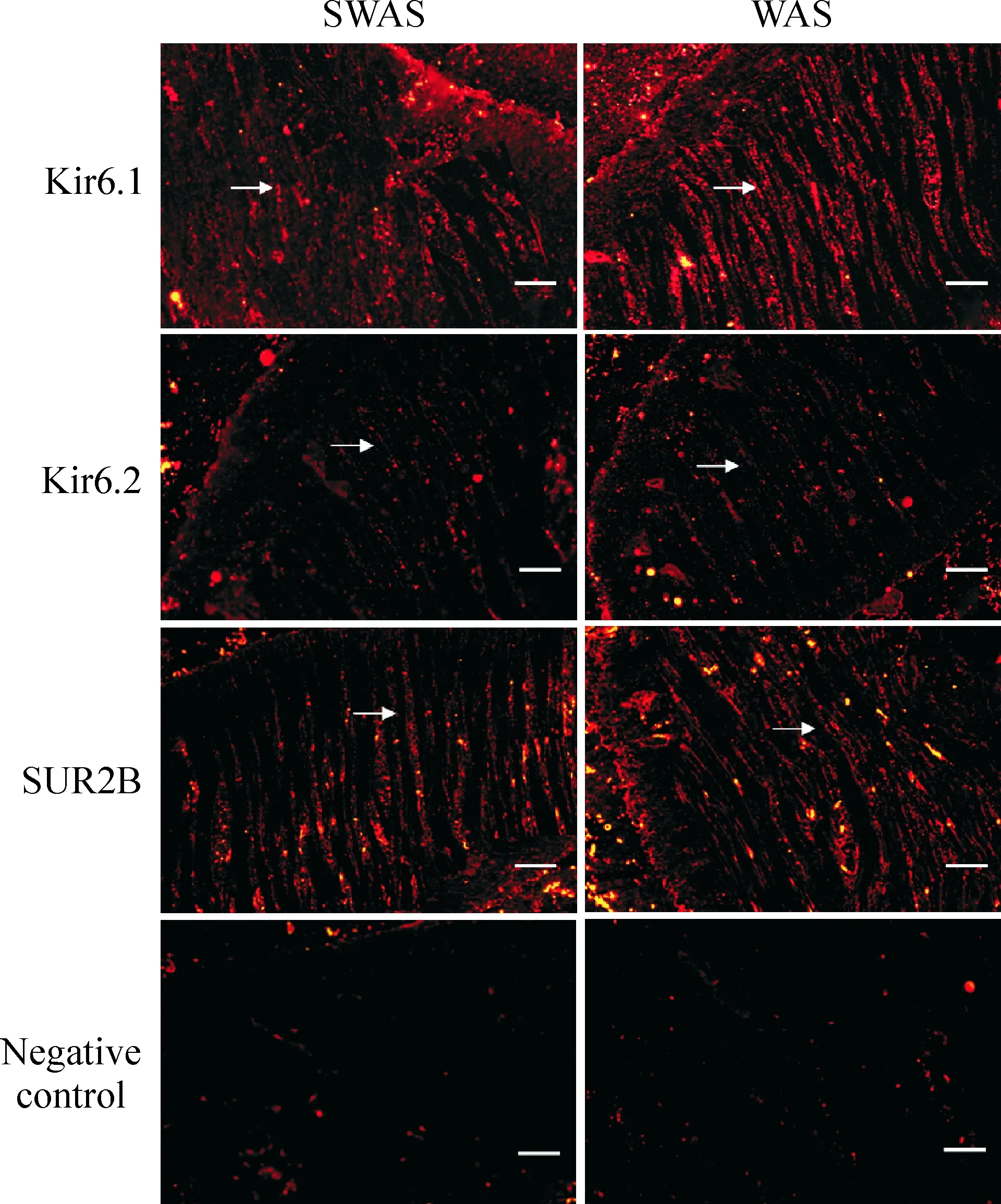

4 KATP通道各亚基在大鼠结肠中的分布

在2组大鼠的结肠组织中,Kir6.1、Kir6.2和SUR-2B在LM和CM细胞膜均有分布;Kir6.1和SUR-2B表达较强,而Kir6.2表达较弱,见图4。

5 WAS增加KATP通道亚基蛋白的表达

Western blotting实验结果显示WAS组大鼠的Kir6.1和SUR2B蛋白表达高于SWAS组(均P<0.01),而Kir6.2的表达无显著差异,见图5。

讨 论

KATP通道是H2S主要的靶通道[8, 14, 16-17],H2S通过开放KATP通道,增加KATP电流,使细胞膜超极化,进而舒张平滑肌,调节消化道动力。本实验制作WAS大鼠模型并通过肌条实验证实结肠LM及CM收缩活性均高于对照组;而WAS结肠动力增加与局部肠道内源性H2S合成减少与结肠高动力相关[15]。使用H2S外源性供体NaHS作用于大鼠肌条以观察外源性H2S对WAS结肠高动力的影响,结果显示NaHS均抑制SWAS和WAS大鼠结肠LM和CM自发性收缩,抑制效应呈浓度依赖性,这与既往的研究一致[7-8, 11, 18-19];而使用KATP通道阻断剂格列苯脲预处理后,NaHS 的抑制效应明显减弱,进一步证实NaHS的抑制作用通过KATP通道介导。

Figure 2.NaHS inhibited contractile activity of colonic strips. A, B: representative effects of different concentrations of NaHS on spontaneous contraction of colonic smooth muscle strips in the SWAS and WAS rats; C, D: the concentration-dependent curve fitting showing that NaHS inhibited contractile activity of LM and CM in both SWAS and WAS rats. IC50values of NaHS for the WAS rats were lower than those for the SWAS rats. Mean±SD.n=10.

图2 NaHS抑制大鼠结肠平滑肌条收缩活性

KATP通道是由Kir亚基和SUR亚基组成,Kir和SUR按1∶1比例相连,以四聚体模式构成八聚体(SUR/Kir6.X)4复合物。Kir构成KATP穿通孔道,具有内向整流的特性;SUR是KATP通道的调节亚基,是KATP通道开放剂或抑制剂作用靶点。不同KATP通道亚基组成形式体现不同生物物理学、药理学以及新陈代谢特性。Kir6.1/SUR2B和Kir6.2/SUR2B是胃肠平滑肌细胞KATP通道的主要构型[20-21]。表达Kir6.1的KATP通道电导为35 pS, 表达Kir6.2的为80 pS,而消化道平滑肌KATP单通道电导为42 pS,提示Kir6.1是胃肠平滑肌KATP通道主要的成孔亚基[20]。本实验证实大鼠结肠平滑肌有Kir6.1、Kir 6.2和SUR2B的分布。

本研究发现WAS组结肠肌条收缩活性高于对照组,但WAS组NaHS IC50明显低于SWAS组,提示WAS组肌条对NaHS的抑制作用具有更高的敏感性,其是否通过KATP通道的可塑性变化实现,如可增加KATP通道数量或提高该通道功能(如开放频率)等;Western blotting结果显示WAS大鼠Kir6.1和SUR2B蛋白表达增加,Kir6.2表达无改变,提示WAS可引起KATP通道数量增加。Kir6.1/SUR2B表达增加的原因仍不清楚,这种可塑性变化可能为动物对应激原的一种适应性反应,通过提高KATP通道数量从而增加对开放剂(如H2S)的敏感性,从而纠正肠道功能紊乱并改善症状。本实验尚未对KATP通道功能进行研究,WAS时KATP通道功能是否存在变化有待于膜片钳等电生理实验进一步证实。

Figure 3.Inhibitory effect of NaHS was reversed by glibenclamide. A, C: representative effects of different concentrations of NaHS on spontaneous contraction of colonic smooth muscle strips in the SWAS and WAS rats after the incubation with glfibenclamide (10 μmol/L); B, D: the concentration-dependent curve tting showing that glybenclamide signi cantly reduced the inhibitory effect induced by H2S. NaHS (1 mmol/L) only caused 30%~45% of inhibition with previous addition of gli-benclamide. Mean±SD.n=10.

图3 格列本脲减弱NaHS对大鼠结肠平滑肌收缩的抑制效应

Figure 4.Distribution of subunits of KATPchannels (immunohistochemical staining, scale bar=20 μm).

图4 KATP通道各亚基在大鼠结肠中的分布

H2S在消化道具有保护黏膜、调节白细胞黏附和聚集、抗炎等作用,对多种消化道疾病具有潜在的治疗作用,如H2S供体或H2S合成的底物L-半胱氨酸可维持胃黏膜完整、促进大鼠胃溃疡愈合[22];抑制H2S的合成可使肠道环氧化酶2的mRNA表达和前列腺素的合成下调,导致结肠炎症和黏膜损伤,结肠内灌入H2S供体明显减轻结肠炎严重性和降低炎症介质如肿瘤坏死因子α mRNA的表达[23-24]。本实验体外研究显示WAS大鼠NaHS的IC50明显低于对照组,可能源于平滑肌细胞上Kir6.1和SUR2B表达上调,提示WAS大鼠结肠对NaHS具有更高的敏感性,外源性的H2S对改善慢性应激引起的结肠高动力具有潜在的治疗价值。

H2S的生理、药理及毒副作用受到广泛关注。人体中H2S的血清浓度为10~100 μmol/L[25],在生理浓度时H2S对维持内环境的稳态具有一定作用,但一旦超过生理浓度H2S具有潜在的毒性作用,如诱发DNA损伤和抑制线粒体细胞色素C氧化酶等[26-27];毫摩尔浓度的H2S对结肠细胞即有害作用[28];而且H2S的生理和毒性作用间的浓度梯度非常小[26];此外除肠道组织本身外,肠腔内还有大量细菌来源的H2S并影响着局部肠道的生理功能,对肠道某些病理生理状态起着保护抑或损伤作用。体外实验发现在慢性WAS结肠动力增高时,NaHS抑制结肠LM和CM收缩的IC50分别为0.203 mmol/L、0.144 mmol/L,此种浓度在发挥改善动力紊乱作用的同时是否存在对结肠组织的毒副作用有待于进一步的研究。

Figure 5.Protein expression of subunits of KATPchannels in colonic tissues. Mean±SD.n=10.**P<0.01vsSWAS group.

图5 2组大鼠结肠KATP通道各亚基蛋白表达

[1] Liang C, Luo H, Liu Y, et al. Plasma hormones facilitated the hypermotility of the colon in a chronic stress rat model [J]. PLoS One, 2012, 7(2): e31774.

[2] Choudhury BK, Shi XZ, Sarna SK. Norepinephrine mediates the transcriptional effects of heterotypic chronic stress on colonic motor function [J]. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol, 2009, 296(6): G1238-G1247.

[3] Ataka K, Nagaishi K, Asakawa A, et al. Alteration of antral and proximal colonic motility induced by chronic psychological stress involves central urocortin 3 and vasopressin in rats [J]. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol, 2012, 303(4):G519-G528.

[4] Bulbul M, Babygirija R, Cerjak D, et al. Impaired adaptation of gastrointestinal motility following chronic stress in maternally separated rats [J]. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol, 2012, 302(7):G702-G711.

[5] Li Q, Sarna SK. Chronic stress targets posttranscriptional mechanisms to rapidly upregulate alpha1C-subunit of Cav1.2b calcium channels in colonic smooth muscle cells[J]. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol, 2011, 300(1):G154-G163.

[6] Bradesi S, Schwetz I, Ennes HS, et al. Repeated exposure to water avoidance stress in rats: a new model for sustained visceral hyperalgesia [J]. Am J Physiol Gastroin-test Liver Physiol, 2005, 289(1): G42-G53.

[7] Teague B, Asiedu S, Moore PK. The smooth muscle relaxant effect of hydrogen sulphideinvitro: evidence for a physiological role to control intestinal contractility[J]. Br J Pharmacol, 2002, 137(2):139-145.

[8] Gallego D, Clave P, Donovan J, et al. The gaseous mediator, hydrogen sulphide, inhibitsinvitromotor patterns in the human, rat and mouse colon and jejunum[J]. Neurogastroenterol Motil, 2008, 20(12):1306-1316.

[9] Gil V, Parsons S, Gallego D, et al. Effects of hydrogen sulphide on motility patterns in the rat colon[J]. Br J Pharmacol, 2013, 169(1):34-50.

[10]Szabo C. Hydrogen sulphide and its therapeutic potential [J]. Nat Rev Drug Discov, 2007, 6(11):917-935.

[11]Zhao P, Huang X, Wang ZY, et al. Dual effect of exogenous hydrogen sulfide on the spontaneous contraction of gastric smooth muscle in guinea-pig[J]. Eur J Pharmacol, 2009, 616(1-3):223-228.

[12]Distrutti E, Sediari L, Mencarelli A, et al. Evidence that hydrogen sulfide exerts antinociceptive effects in the gastrointestinal tract by activating KATPchannels[J]. J Pharmacol Exp Ther, 2006, 316(1):325-335.

[13]Jimenez M. Hydrogen sulfide as a signaling molecule in the enteric nervous system[J]. Neurogastroenterol Motil, 2010, 22(11):1149-1153.

[14]Linden DR, Levitt MD, Farrugia G, et al. Endogenous production of H2S in the gastrointestinal tract: still in search of a physiologic function[J]. Antioxid Redox Signal, 2010, 12(9):1135-1146.

[15]Liu Y, Luo H, Liang C, et al. Actions of hydrogen sulfide and ATP-sensitive potassium channels on colonic hypermotility in a rat model of chronic stress [J]. PLoS One, 2013, 8(2): e55853.

[16]Nagao M, Duenes JA, Sarr MG. Role of hydrogen sulfide as a gasotransmitter in modulating contractile activity of circular muscle of rat jejunum[J]. J Gastrointest Surg, 2012, 16(2): 334-343.

[17]Gade AR, Kang M, Akbarali HI. Hydrogen sulfide as an allosteric modulator of ATP-sensitive potassium channels in colonic inflammation[J]. Mol Pharmacol, 2013, 83(1): 294-306.

[18]Dhaese I, Lefebvre RA. Myosin light chain phosphatase activation is involved in the hydrogen sulfide-induced relaxation in mouse gastric fundus[J]. Eur J Pharmacol, 2009, 606(1-3):180-186.

[19]Dhaese I, Van Colen I, Lefebvre RA. Mechanisms of action of hydrogen sulfide in relaxation of mouse distal colo-nic smooth muscle[J]. Eur J Pharmacol, 2010, 628(1-3):179-186.

[20]Jin X, Malykhina AP, Lupu F, et al. Altered gene expression and increased bursting activity of colonic smooth muscle ATP-sensitive K+channels in experimental colitis[J]. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol, 2004, 287(1):G274-G285.

[21]Jun JY, Kong ID, Koh SD, et al. Regulation of ATP-sensitive K+channels by protein kinase C in murine colonic myocytes[J]. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol, 2001, 281(3):C857-C864.

[22]Wallace JL, Dicay M, McKnight W, et al. Hydrogen sulfide enhances ulcer healing in rats[J]. FASEB J, 2007, 21(14):4070-4076.

[23]Wallace JL, Vong L, McKnight W, et al. Endogenous and exogenous hydrogen sulfide promotes resolution of colitis in rats[J]. Gastroenterology, 2009, 137(2):569-578.e1.

[24]Fiorucci S, Orlandi S, Mencarelli A, et al. Enhanced activity of a hydrogen sulphide-releasing derivative of mesalamine (ATB-429) in a mouse model of colitis[J]. Br J Pharmacol, 2007, 150(8):996-1002.

[25]Gravanis A, Makrigiannakis A, Zoumakis E, et al. Endometrial and myometrial corticotropin-releasing hormone (CRH): its regulation and possible roles[J]. Peptides, 2001, 22(5):785-793.

[26]Wang R. Two’s company, three’s a crowd: can H2S be the third endogenous gaseous transmitter? [J]. FASEB J, 2002, 16(13):1792-1798.

[27]Attene-Ramos MS, Wagner ED, Gaskins HR, et al. Hydrogen sulfide induces direct radical-associated DNA damage[J]. Mol Cancer Res, 2007, 5(5):455-459.

[28]Babidge W, Millard S, Roediger W. Sulfides impair short chain fatty acid beta-oxidation at acyl-CoA dehydrogenase level in colonocytes: implications for ulcerative colitis [J]. Mol Cell Biochem, 1998, 181(1-2):117-124.

Effect of exogenous H2S and ATP-sensitive potassium channels on colonic hypermotility in a rat model of chronic stress

LIU Ying1, QUAN Xiao-jing2, XIA Hong2, LUO He-sheng2

(1DepartmentofGastroenterology,TheAffiliatedHospitalofGuilinMedicalCollege,Guilin541001,China;2DepartmentofGastroenterology,RenminHospitalofWuhanUniversity,Wuhan430060,China.E-mail:liuy1009@sina.com)

AIM: To investigate the potential role of exogenous hydrogen sulfide (H2S) and ATP-sensitive potassium (KATP) channels in chronic stress-induced colonic hypermotility. METHODS: Male Wistar rats were divided into water avoidance stress (WAS) group and sham WAS (SWAS) group. Organ bath recordings were used to test the contractile activity of colonic strips. The effects of H2S donor NaHS and pretreatment with glibenclamide on the contractions of colonic smooth muscle were studied and the IC50of NaHS was calculated. The localization and expression of the subunits of KATPchannels were determined by the methods of immunohistochemistry and Western blotting. RESULTS: WAS increased contractile activity of colonic strips. NaHS concentration-dependently inhibited the spontaneous contractions of strips from the SWAS and WAS rats. The IC50of NaHS for longitudinal muscle (LM) and circular muscle (CM) of the WAS rats was 0.2033 mmol/L and 0.1438 mmol/L, significantly lower than those of the SWAS rats. Glibenclamide significantly increased the IC50of NaHS for LM and CM from the SWAS and WAS rats. In both SWAS and WAS rat colon, Kir6.1, Kir6.2 and SUR2B were expressed on the plasma membrane of the smooth muscle cells. WAS treatment resulted in up-regulation of the expression of Kir6.1 and SUR2B in the colon devoid of mucosa and submucosa. CONCLUSION: The increased expression of Kir 6.1 and SUR2B in colonic smooth muscle cells may be a defensive response to chronic WAS. H2S donors may have potential clinical effect on treating chronic stress-induced colonic hypermotility.

Chronic stress; Hypermotility; Hydrogen sulfide; ATP-sensitive potassium channels

1000- 4718(2015)04- 0725- 07

2014- 11- 05

2015- 01- 08

国家自然科学基金资助项目 (No. 81460111);广西自然科学基金资助项目(No. 2014GXNSFAA118166);广西壮族自治区卫生厅计划课题(No. Z2012408)

R333.3; R363.2

A

10.3969/j.issn.1000- 4718.2015.04.027

△通讯作者 Tel: 0773-2823740; E-mail: liuy1009@sina.com