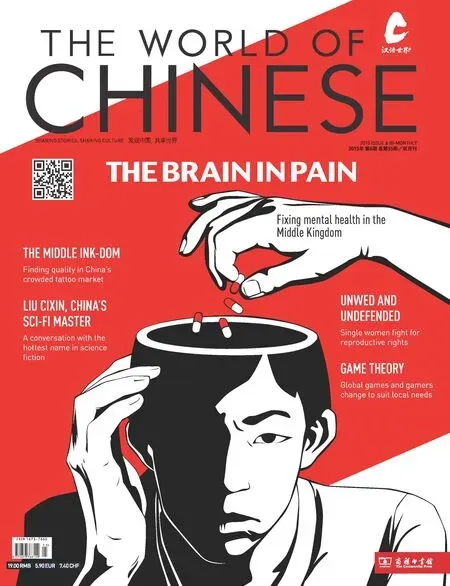

THEBRAININPAIN

THEBRAININPAIN

The problems with and solutions for China’s mental health worries

是患者欲语还休的隐痛,

也是医者力不从心的无奈;

面对当今社会的精神健康问题,

仁心之外,仍需仁术

ON THE OUTSlDE, SUFFERERS ARE WHlTE-COllAR WORKERS, COllEGE STUDENTS, MOTHERS AND FATHERS, AND PERHAPS SOMEONE ClOSE TO YOU. MENTAl HEAlTH PROBlEMS MANlFEST lN A NUMBER OF WAYS, SOMETlMES SElF-HARM, DEPRESSlON, OR AN lNABlllTY TO WORK WlTH OR CARE FOR OTHERS. THE WORST PART ABOUT All OF THlS lS THAT lT’S A DlSEASE NO ONE CAN SEE, A PROBlEM PEOPlE TRY TO “GET OVER” llKE lT’S THE FlU. BUT, WlTH CHlNA’S ADVANCES lN SO MANY FlElDS, THE AREA OF MENTAl HEAlTH CARE lS WOEFUllY BEHlND THE TlMES, AND THE AUTHORlTlES AND SUFFERERS KNOW THAT lT’S TlME TO CHANGE BOTH POllCY AND MlNDS. SOME FlND THEMSElVES MlRED lN AN lMPOSSlBlE PUBllC SYSTEM OR STUCK lN A TOOTHlESS PRlVATE AlTERNATlVE. OTHERS ARE DlSCOVERlNG THAT THElR DlSEASES ARE NOTHlNG TO BE ASHAMED OF; THEY’RE SOMETHlNG TO BE TREATED. AND, STlll, OTHERS TOll AWAY lN OBSCURlTY lN A MENTAl HEAlTH CARE SYSTEM THAT OFFERS THEM lOW BENEFlTS AND HlGH DANGER. lT MAY BE TREATED llKE AN lSSUE THAT AFFllCTS AN UNlUCKY FEW, BUT lT’S A PROBlEM WE All HAVE TO FACE.

FAllURES PRlVATE AND PUBllC

People started waiting outside the Beijing Anding Hospital around six in the morning. Yue Gui, 30, sits on a suitcase with her son sleeping in her arms. She refuses to move and glares at the boy’s father who wants a smoke; the father tucks the cigarette back behind his ear.

The family came from Langfang, Hebei Province, less than 70 kilometers away from the capital, and it’s their second day waiting. They failed to register yesterday, so they came one hour earlier this time. “Our plan is to stay only for three days,” Yue says, concerned for her four-yearold son who rarely speaks and keeps tearing out his hair. The father had his son’s head shaved, but the boy would still scratch his head until it bled. Wearing a knitted yellow hat made for him by his grandmother, the boy sleeps carefully and Yue lifts his hat to wipe away the sweat.

The local hospital in Langfang failed to provide a solution, simply giving the child some pills to keep him sedated. “Go see a psychiatrist in Beijing,” the doctor suggested.

The family soon learned that there are several famous mental hospitals in the capital and then quickly learned that all of them are crowded. “We picked the most famous one. We have to wait anyway.”

Under the haze of the Beijing smog, Yue notices more people with suitcases—hoping to keep the cost of accommodation down as much as possible. Standing in the front of the row, she knows she’ll get registered today. “But I guess they won’t be able to make it,” she says, pointing to newcomers.

Beijing hospitals usually book 50 percent of appointment quotas online, reserved three weeks in advance, and keep open a certain number for clinic registration. The situation in Beijing’s other two mental hospitals, Peking University Sixth Hospital and Beijing Huilongguan Hospital, is similar. Visitors can be seen chewing bread for lunch and taking pre-dawn naps, leaning against the hospital lobby wall.

The government’s five-year plan on mental health (2015 – 2020) issued by the State Council this year states that the lack of mental health care services is at least partly due to a grave lack of psychiatrists in China. Chinese Center for Disease Control and Prevention data states that the country has over 100 million people who suffer mental disorders and 4.3 million severely mentally-impaired patients were officially recorded at the end of 2014, more than 55 percent of whom live in poverty.

But there are only 20,000 psychiatrists, all working in big hospitals in first-tier cities and provincial capitals.

“Problems caused by the shortage could have been solved if private mental health counselors were allowed to treat patients,” says Zhu Jianmin, head of the Psychological Department at Beijing Forestry University. In May 2013, China’s first mental health law took effect. Under the law, every mental illness diagnosis must be made by a “qualified psychiatrist” and private mental health counselors have no right to diagnose or give medical treatment regardless of qualifications.

Although many private counselors are still practicing, considered as a necessary approach worldwide to deal with mental health issues, patients reserve the right to sue if the counselors ever tell the patient they’re suffering from something as remedial as depression or attempt to treat them.

The five-year plan set a goal of managing more than 80 percent mental illnesses patients by 2020 and raise the number of doctors specializing in mental disorders to 40,000 by 2020, but the situation is complex. Without

28the assistance of private counselors, there won’t be enough doctors, even with 40,000 psychiatrists, and private counselors will be less willing to treat given the risks. As such, the whole process of private mental health care might find itself going underground, making the counseling industry more difficult to regulate and improve. While legality is certainly a problem, time, training, and money is what most stands in the way.

Xiao, a 30-year-old IT engineer who suffers from severe anxiety, waits for his third psychotherapy session at Anding Hospital, repeatedly playing ringtones, stressed about which one he should choose. His counselor, who’s also a psychiatrist, recommended five sessions of at least 40 minutes. His last session was three months ago. During those three months Xiao had no problem falling asleep, “thanks to the sedatives.”

“But I’m afraid my counselor had forgotten me and my condition,” he added, worrying that he won’t be able to rely on getting a prescription. He’s probably right. At the Peking University Sixth Hospital, a doctor sees around 20 patients in half a day, sparing only ten minutes for each visitor for diagnoses and prescriptions. Not many doctors have the time for time-consuming counseling.

“Most of these doctors are psychiatrists...prescriptions are their specialty,” says Xiong Pengdi, a fresh master’s graduate in psychology. She has no plans to work in a public mental institution, echoing a common allegation against psychiatrists shared by many psychologists: “Selling drugs to patients generates more profit than psychotherapy.”

However, the public option has more attractive prices when it comes to counseling; one only has to pay 20 to 50 yuan for 20 minutes at a public hospital while the price in counseling centers range from 100 to 1,000 yuan per hour. But to be fair, many mental disorders require medication. The argument of drugs versus therapy is as old as Freud.

Dong Wentian, deputy head of Peking University Sixth Hospital, admits that doctors in public institutions do not have as much time as private counseling centers. In the three stages—prevention, treatment, and recovery—public hospitals focus more on treatment, he says. “A good sign is that many academic lecturers are about talking therapy, and I can see more psychiatrists attending,”Xiong says.

But, the same old problem remains: public institutions are rushed off their feet. Cui Yonghua, a top psychiatrist and a psychologist with Anding Hospital, initiated a private clinic, Mind Rainbow, in August. It’s Beijing’s first private mental health clinic. Different from counseling centers, this one has medical certificate and a real reputation because it was formed by the city’s most prestigious mental health professionals from public hospitals.

With more than ten years of clinical experience, Cui knows more than anyone the rush of the public option—how frustrating it was to not remember a patient’s condition. But not every private institution can enjoy the same level of credibility as Cui’s upstart clinic

Many patients suffering often only seek help when their illness is affecting their work or their lives. Choosing from among the thousands of counseling centers is a chore in itself.

There are at least 200,000 counselors holding the “National Mental Health Consultant, Level 2” certificate from the Ministry of Human Resources and Social Security. Passing the paper examination and getting this certificate is only the start for a professional consultancy, says Sun Yuwei, a counselor with ten years of experience. In this sense, she says, the law forbidding private centers from diagnosing and giving treatment makes sense.

As a psychologist and a counselor, Zhu says it’s almost impossible, under the current mental health law for a private counseling center to promote itself in public. “What should they boast about? The cure rate? No, they’re not allowed to say they can cure a patient,” he says.

At the end of the day, the family from Langfang finally got to see a doctor who asked the child and parents a few questions—language ability, sleeping and eating habits, and the parents’ work schedule. To Yue’s amazement, the doctor said her son might be suffering from autism.

The doctor prescribed three different medications and asked her to come again one month later. She also asked the family to get the child registered at a training center for autistic children. Kindergartens are not for him, the parents learned.

- llU SHA 〔刘莎〕

29

TOll AND TURMOll

Social stigma, difficulty finding a husband, the risk of being beaten, and a paltry salary; these are the ingredients that make up life for nurses on the front lines dealing with the mentally ill.

China may have rapidly developed over the last few decades, but often it seems like some areas have scarcely progressed at all. Headlines occasionally tell horror stories of the mentally ill in the countryside. At best they tend to have caring but uneducated family members looking after them, at worst they can be abused, chained, or locked up for years, or sometimes enslaved to work in brick kilns.

Sadly, these harrowing tales do not translate into widespread public respect for mental health care workers. A 2014 report in the Nanfang Metropolis Daily profiled Wang Juming, a mental health worker from the People’s Fourth Hospital. She told the newspaper that “the first thing we should learn is how to protect ourselves”. She carries a scar on her arm from an attack in which a male nurse was stabbed in the face with a fork.

Having been a nurse for over 20 years, she is one of the most highly-paid nurses in her ward. Her reward? A salary of just over 3,000 RMB per month.

The risk of violence is so pervasive that the Peking University Sixth Hospital has recently been trying to increase their proportion of male nurses, currently standing at about 30 out of 300. Not for gender-diversity reasons mind you, simply because, as Dong Tianwen, deputy director of the hospital puts it, “They have more strength to stop a patient killing himself/herself or halt physical confrontations between patients.”

In September the Guizhou Metropolis Daily ran a series of reports on various careers in the Anshun area. When profiling psychiatric nurse Wang Wanlu, it chose “fear”as the keyword for her working life. “Lighters, glasses, rope, and other items all become dangerous items. To these patients, anything can be a weapon,” the report said, citing Wang as saying that the nurses have often become desensitized to the suffering of the patients because if they care too much, they are sure to suffer themselves. “If we know he’s ill and we still care, isn’t it like giving yourself a hard time?”

It’s not just the risk of physical violence that troubles workers in the mental health care sector. The stress is often pervasive and ongoing, making the profession unattractive to new recruits, creating a vicious cycle where staff tend to be overworked and unappreciated.

According to a report by the World Psychiatric Association (WPA) in 2011, which outlined many of the problems with China’s mental health system, most of China’s mental health professionals are psychiatrists or psychiatric nurses, with few clinical psychologists and social workers. Licensing is carried out by the Ministry of Health and the Ministry of Human Resources and Social Security. It is difficult to come by concrete statistics for the number of professionals throughout the country, but in 2004, they stood at 16,103 licensed psychiatrists or registrars, and 24,793 licensed psychiatric nurses according to the WPA report, and ten years later it’s believed there are only about 20,000 licensed psychiatrists—an alarming figure for the country with the world’s largest population. Media reports of extensive violence wracking the sector are likely to have helped keep growth fairly stagnant.

The problem is compounded by the many con artists that operate substandard mental health clinics, with a representative from the Division of Clinical Psychology under the Hong Kong Psychological Society telling CNN in 2014 that many of the complaints they receive are due to unprofessional therapists with dubious credentials who often break confidentiality or worse.

Shi Wei, director at the student mental health counseling center at the Beijing University of Foreign Studies, told TWOC that working as a counselor or psychiatrist involves many risks, of both the physical and mental varieties. He said that while he hasn’t been physically hurt himself, he has seen people break down under the intense pressure of the job and that during counseling sessions, “you have to monitor the student’s emotional state at all times. I have at times felt very nervous”.

In addition, mental health workers have to deal with worries from broader society as well. Wang Wanlu, for example, may be past the “leftover woman” age of 25 in China, but she is still relatively young and attractive in a society with a surplus of men. Despite this fact, she has trouble dating. “People run away as soon as they know you work in a mental hospital,” Wang Wanlu told the paper. “All seven nurses in the hospital are women. All are around 28, but only three of them have found boyfriends.”

Such tales are far from rare. In 2013, Wang Di, a psychiatrist with Beijing’s Anding Hospital, told the Beijing News that she felt there was a stigma about herjob and that people had pulled out of blind dates as soon as they learned her profession.

Even in cases when patients do recover, societal attitudes help push them back toward mental care. Wang Wanlu told the newspaper that they often face discrimination, which hinders their recovery, and even just the fact they spend time in a mental institution is enough to get them ostracized. In one sad case, family members even just tried to make excuses to avoid coming to retrieve their family member.

The result is often patients spending much longer than necessary in hospital; in rare cases some even stay for over 20 years. Attitudes expressed in forums online often link the mentally ill with violence, and by extension, mental health care workers are often assumed to have problems as well.

The problems are just as pronounced for mental health care workers outside the hospital, and their different employment status creates its own problems.

Sun Yuwei, a private counselor, told TWOC that some unstable visitors collapse during counseling and that their behavior can be unpredictable. This can be particularly problematic as these counselors are not qualified to dispense any drugs, which means they can’t use items like sedatives or tranquilizers to calm patients in an emergency situation.

Family attitudes play a role as well. The Guizhou Metropolis Daily also spoke to Wang Jing, a colleague of Wang Wanlu, who mentioned that her family disapproves of her job. Despite this, she enjoys her work and points out that it does have its rewards.

“I don’t regret coming to work here,”she said, pointing out that seeing patients recover is a reward on its own. Her parents, unfortunately, don’t see it that way. Once upon a time they were proud of her, but now they don’t like to talk about her job due to its low status and poor financial rewards.

There has been some progress in mental health care of course, but as with most legislation in China, enforcement remains patchy at best and it can be difficult to see improvements at the ground level. A 2013 Mental Health law banned house calls by doctors in an effort to protect their safety from potentially violent patients. The law included a raft of other optimistic improvements, but doctors, particularly those at the county level, say they haven’t noticed any real improvements. Ultimately, the quality of life of China’s mental health care workers is inextricably linked with the quality of life of the mentally ill, and until such time as society more fully recognizes the need to help these people rather than ostracize them, mental health care workers are likely to continue to suffer in silence.

- DAVlD DAWSON

31

NEW SOlUTlONS FOR NEW DlSORDERS

When bipolar disorder hit Yangu Moqing, a 28-year-old college instructor of biochemistry in Guizhou Province, he was initially defensive. “I was first diagnosed with depression while I was in graduate school in 2006, but I didn’t take it seriously and refused to take any medicine,” Yangu says, preferring to use an assumed name. “Two years later, I suffered a serious relapse.” While he doesn’t go into this further, the incident clearly affected Yangu deeply.

“I realized I needed help,” Yangu admits. “I turned to a new doctor and after a long period of observation, it was confirmed that I had bipolar disorder...I have to take medicine for the rest of my life.” His college mates and professors know about his condition, but he won’t tell the university at which he teaches.

Bipolar disorder, characterized by a alternation between episodes of depression and mania, affects around 60 million people worldwide and is responsible for the loss of more disability-adjusted life years (DALY) than cancer according to the World Health Organization, mainly because it involves an early onset and a lifetime of struggling with symptoms. But, sometimes, sufferers don’t get a lifetime. It is estimated that 25 to 50 percent of bipolar patients attempt suicide at least once at some point according to John Hopkins University, and ten percent of those attempts are successful. In China the disease remains relatively obscure.

Diagnosing bipolar disorder is notoriously difficult, requiring a detailed medical history, close observation, and constant communication between patient and doctor. Dr. Cui Yong, chief physician at Beijing Huilongguan Hospital, a first-class psychiatric hospital and one of the three largest psychiatric hospitals in China, explains: “Mental illness is a subjective experience. It’s not like you can do a CT scan or MRI of the brain and instantly know what’s going wrong. It requires a lot of selfreporting and long-term monitoring. From time to time, I would get calls from patients’ relatives asking for my diagnoses via phone. I told them it was impossible,” Cui states, adding that the treatment is even more difficult.“The medication dosages have to be adjusted gradually, and this kind of medicine is highly personalized depending on the requirements of the individual.”

Exactly how many people nationwide are suffering from bipolar disorder is unknown. The latest national survey conducted in theearly 1980s showed a mere 0.042 percent suffering from this disorder, whereas North American research data states that three percent of the general population suffers from bipolar disorder. Even in the US, it is estimated that more than half of bipolar sufferers do not receive treatment, and the numbers are likely to be higher in China.

There are certainly historical reasons for low awareness in China’s underdeveloped mental health industry. Modern psychiatry entered China only about a century ago, in the first half of which the country was torn by warfare and chaos. In the 1950s and 60s, although the new trend psychoanalysis was all the rage in the West, behavioral psychology still dominated the psychiatric field in China due to the influence of the former Soviet Union. Over the next decade amidst the Cultural Revolution, Western science was denounced and psychiatrists turned to traditional Chinese medicine for salvation. In an extreme case reported by People’s Daily in 1971, a hospital treated mental patients successfully with Mao Zedong Thought. “To overcome mental disorder requires mental power; to treat mental illness requires invincible Maoist thought,”the doctors were quoted as saying.

The situation changed in the 1980s as China strove to catch up. Until 2001, homosexuality was still listed as a mental disorder in the Diagnostic Criteria of Mental Disorders, a standard guide for mental health practices. The study of bipolar disorder lagged behind as a result, and with it public awareness.

On rare occasions, bipolar disorder manages to get on the public’s radar, often when a celebrity breaks the news. Back in 2013, author of the bestselling book series The Grave Robbers’Chronicles, Nanpai Sanshu, declared on Weibo that he would give up writing at the peak of his career as well as his marriage of ten years. “Sorry, I can’t take it anymore,” he wrote. His family later revealed that he had been diagnosed with bipolar disorder and schizophrenia a few months earlier and had refused treatment ever since. Online rumors whirled that he had even killed himself. The term “crazy”was used with careless abandon.

“It was a bizarre feeling; you sit in a spot where people rarely sit and see the world from a strange angle. You think of all the people you know, none will ever understand your view,”he wrote in the afterword of his last book before giving up his writing. “No matter who you are, the world ignores you in such a state.” Nanpai Sanshu was eventually admitted to hospital to receive treatment.

It’s not news to say that mental patients are targets of discrimination, often choosing to stay quiet about their condition. “There are not many patients who voluntarily open up about their illness. Most are forced to when they have an episode in the work place,” says Yangu Moqing.

“People see them as ‘abnormal’.”

In Yangu Moqing’s opinion, discrimination is a deeply-rooted problem that exists everywhere: the public, medical care providers, and, worst of all, the sufferers themselves.“Schizophrenia is the lowest on the mental illness ladder,” he says.“Patients with depression may look down on them and say ‘at least I’m not a psycho’.”

The fight against bipolar disorder is a lonely one, but the brave are trying, not just for themselves but for the community as a whole. They see light in the virtual world where anonymity and privacy protect them. Nowadays, Yangu Moqing spends three to four hours every day after work managing one of the largest online forums about mental health, “The Sunshine Project”. Ten years since its establishment, the forum now has more than 76,000 registered members and nearly 100,000 discussion topics.“Most of my team members are also long time mental patients; the rest are medical professionals,” Yangu explains. “We offer a platform for all patients and those who suspect they have mental disorder to share doubts and experience; more importantly, it offers a sense of belonging to the scared and the confused.”

He has also answered over 800 questions regarding bipolar disorder and other mental illnesses for anyone who’s interested in the subject on the largest knowledge-sharing website in China, Zhihu, with his expertise and experience. Stating that the mission is a public service, Yangu Moqing says, “What mental patients need is not just medical care or legal protection, but also attention, acceptance, understanding, and respect from society, humanistic care. To inform the public on mental health is a fundamental way to eliminate discrimination—a task our generation has to take on for a better future.”

On the recent progress at medical institutions, the Beijing Huilongguan Hospital established the first support group for bipolar patients, Affective Disorder Anonymous (ADA), in April. Patients meet every month in person and stay in touch via a Wechat group to discuss their condition with therapists. The hospital also offers lectures for the public on mental health issues every month. In the latest lecture, Dr. Cui ended his talk with a scene from A Beautiful Mind when John Nash thanks his wife in his Noble Prize acceptance speech after years of battling his mental illness, “It is only in the mysterious equations of love that any logic or reasons can be found.” It was a warm note for the audience, but in reality, helping bipolar patients requires more than just love. - llU JUE 〔刘珏〕

34