A Thousand Words:Writing from Photographs

∷安妮 选译

I can’t remember exactly when I stopped carrying a notebook. Sometime in the past year, I gave up writing hurried descriptions of people on the subway, copying the names of artists from museum walls and the titles of books in stores, and scribbling1. scribble: 潦草地书写,胡写。down bits of phrases overheard at restaurants and cafés.

It’s not that my memory improved but,instead, that I started archiving2. archive: 把……存档,把……收集归档。these events and ideas with my phone, as photographs.Now, if I want to research the painter whose portraits I admired at the museum, I don’t have to read through page after page of my chicken scratch trying to find her name.3. chicken: 此处比喻潦草、难看的字迹;scratch: 潦草的字迹,乱写乱画。When I need the title of a novel someone recommended, I just scroll back to the day we were at the bookstore together.

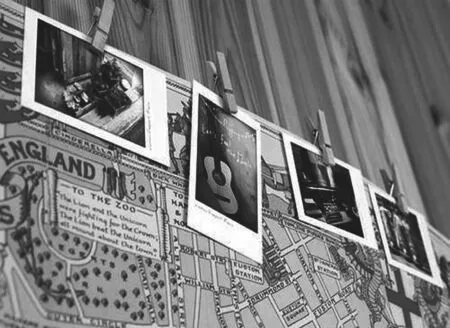

Looking through my photo stream,there is a caption about Thomas Jefferson smuggling seeds from Italy, which I want to research;4. caption:(插图、图片等的)解说词,说明文字;Thomas Jefferson: 托马斯·杰斐逊(1743—1826),第三任美国总统,同时也是《美国独立宣言》的主要起草人,美国开国元勋中最具影响力者之一;smuggle: 偷运,偷带。a picture of a tree I want to identify, which I need to send to my father;the nutritional label from a seasoning5. seasoning: 调味料,调味品。that I want to re-create; and a man with a jungle of electrical cords in the coffee shop, whose picture I took because I wanted to write something about how our wireless lives are actually full of wires. Photography has changed not only the way that I make notes but also the way that I write. Like an endless series of prompts, the photographs are a record of half-formed ideas to which I hope to return.

Last year, I wrote something about a leech salesman whom I’d met in Istanbul.Weeks later, a friend who had been with me in Turkey wrote to say how impressed she was by the particulars that I had been able to recount. “Did you make detailed notes that day, or do you simply remember all this?” she asked. In fact, I had written the essay after studying photographs that I had taken of the man and his leeches. When she praised a speci fic bit of description, I had to admit that it hadn’t come about spontaneously—it was only after looking carefully at the photographs and trying out various metaphors that I settled on the idea that the leeches were gathered around the middle of the bottle like a belt.

Even when I’m writing longhand6. longhand: 手写的(相对于机打而言)。, it’s rare that I do not have my photo gallery open, or have a few photographs in front of me. If I am trying to describe a place, I find pictures that I took of that place; if I am sketching a human subject, I look for images of her.When my own albums fail me, I go down the rabbit hole7. down the rabbit hole: 掉进兔子洞,进入兔子洞。该俗语来源于路易斯·卡罗的作品《爱丽丝漫游奇境记》,故事主角爱丽丝从兔子洞掉进一个奇异的梦幻世界。后来,兔子洞逐渐演变成了“奇异、梦幻世界的入口”之意。of Google image search.

James Wood, inHow Fiction Works, writes that photographs can deaden prose.8. James Wood: 詹姆斯·伍德(1965— ),当代英国著名文学评论家和作家。《小说原理》(How Fiction Works)是其文学批评作品的代表作之一;deaden: 使麻木,使消失;prose: 散文。“There is nothing harder than the creation of a fictional character,”the section on character opens. “I can tell it from the number of apprentice9. apprentice: 新手的,初学者的。novels I read that begin with descriptions of photographs.” By way of illustration,he skewers the kind of writing that is drawn from pictures.10. illustration: 实例,实证;skewer: 一针见血地指出。“You know the style: ‘My mother is squinting in the fierce sunlight and holding, for some reason, a dead pheasant …11. squint: 眯着眼看;pheasant: 野鸡,雉。my father, however, is in his element, irrepressible as ever, and has on his head that velvet trilby from Prague I remember so well from my childhood.12. in one’s element: 处于适宜的环境,如鱼得水;irrepressible:压抑不住的,约束不了的;velvet: 绒的,天鹅绒的;trilby: 软毡帽。’”

Wood’s perfect parody concludes with the indictment that an “unpractised novelist cleaves to the static, because it is much easier to describe than the mobile.”13.parody:(为了嘲弄某作者或某作品而写的)滑稽的模仿作品;indictment: 控诉,谴责; cleave to: 坚持,执著于。By contrast, Don DeLillo14. Don DeLillo: 堂·德里罗(1936— ), 美国散文家、小说家和剧作家。《坠落的人》(Falling Man)和《地下世界》(Underworld)是他的两部代表作。has said that single images inspired some of his novels.Falling Mancame from the curiosity generated by the photograph of that same title, by Richard Drew, a haunting image of a survivor from the attack on the Twin Towers.15. generate: 使形成,使发生;haunting: 不易忘怀的,萦绕于心头的;Twin Towers: 纽约世界贸易中心双子塔,自1973年启用以来其双塔成为了纽约的地标之一,2001年在“9·11”事件中倒塌。Underworldwas sparked by juxtaposed headlines in theNew York Times: “I saw these two headlines, literally, in a pictorial way,” DeLillo said,“the way they were matched,each followed by three columns of type.”16. spark: 点燃,触发;juxtapose:并列,并置;pictorial: 图片的,由图片组成的;type: 印刷文字。

Whole writing exercises are devoted to photographs: choose a picture and create a narrative from its visual content; provide a photograph and ask a writer to use a person or an object in it as a character or prop

for a story.17. narrative: 叙述,故事;prop:道具。Both fiction and non fiction writers walk with this crutch, hobbling their way through writer’s block or memory loss.18Photographs that may deaden the prose of a fiction writer might enliven the work of an essayist; the same photographs that enable the precision of the journalist might inspire the whimsy19of a poet.

Digital photography, endless and inexpensive, has made us all into archivists. And the very act of taking a photograph, now so common, affects how we remember an event. A study by Linda Henkel finds that taking photographs changes the way we experience the world,and reviewing them can change the way we remember the experience. In the article, Henkel relates her findings to other research on taking notes: “Similar to the finding that reviewing notes taken during class boosts retention better than merely taking notes, it may be that our photos can help us remember only if we actually access and interact with them, rather than just amass them.20”

Writing from photographs seems as though it should produce the same effect, sharpening the way we convert experiences and events into prose. I suspect that it also changes not only what we write but how we write it. It’s no coincidence that the rise of the sel fie coincides with the age of autobiography.21. coincidence: 偶然,巧合;sel fie:自拍;coincide: 同时发生,(发生时间)恰好相同。

Photography engenders a new kind of ekphrasis,especially when the writer herself is the photographer.22. engender: 引起,酿成;ekphrasis:符像化,古典修辞学术语,希腊文原意是“说出、充分描述(看到的场景)”。That is why I have found myself so willing to put down my notebooks and rely fully on my photo stream. My photographs are a more useful first draft than my attempted prose was, a richer archive than the pages of my binders. Even this essay came from a “collection”of images: the cover of Joan Didion’s Slouching Toward Bethlehem; a few pictures of speci fic paragraphs;screenshots of the e-mail from my friend and of my essay on the leech gatherer; photographs of the leech salesman, and of two paragraphs from James Wood’s How Fiction Works. As I made my notes, I was scrolling through these images in an album called “bower-bird bric-a-brac nest,” a phrase borrowed from Ted Hughes’s The Literary Life, itself a snapshot of the writer at work.23. bower-bird:〈口〉零星饰物收集者;bric-a-brac: 小摆设,小玩意儿;Ted Hughes: 泰德·休斯(1930—1998),英国诗人和儿童文学作家,1984年被授予英国桂冠诗人;snapshot: 快照,快相。

不知从何时起,我再也不随身携带笔记本了。去年的某个时候,我不再匆匆描写在地铁里擦肩而过的人群,不再记下博物馆墙上艺术家的名字或书店中某些书的书名,也不再在餐馆和咖啡厅里潦草地写下偶然听到的只言片语。

不是我的记忆力增强了,恰恰相反,我开始用手机拍下生活中的各种场景与想法。如今,当我在博物馆里看到喜欢的画作,想要了解它的创作者时,我不需要一页页翻看我那些潦草的笔记,试图搜寻她的名字。当我需要别人推荐的一本小说的书名时,我只需要(在相片库中)往回滚动到我们一起逛书店的那一天。

无论是在微博还是微信上上传照片和感言,对我来说,都是充满乐趣的事,因为这一张张照片定格了人生中的一个个时刻。毋须置疑,它们有着文字所无可比拟的真实与生动,用全新的视角反映自己的“人生之书”。在人类历史上,图片作为一种表达及交流的形式,其力量从未像今天这样强大。它足以媲美文字甚至超越后者,正所谓“一图胜千言”。

翻看我的相片库,有一张关于托马斯·杰斐逊从意大利偷运种子的照片,这是我想研究的话题;有一张树的照片,我想要鉴别那棵树所以需要发给父亲;有一张我想要复制出来的调味料的营养标签;有一张在咖啡厅里身上挂着乱七八糟电线的男子的照片,我把他拍下来是因为我想写一些关于我们的“无线”生活其实是如何充斥着电线的东西。拍照不仅改变了我记录生活的方式,还改变了我的写作方式。恰如源源不断的提醒语,这些照片记录了我尚未完全成形的想法,之后我还想重新审视这些想法。

去年,我写了一些关于我在伊斯坦布尔碰到的一位卖水蛭的人。几周后,与我一同去土耳其的朋友来信说道,我竟然能将这么多细节描述出来,真了不起。“那天你是做了详尽的笔记,还是你把一切都记在脑中了?”她问道。事实上,我是在细细观察了我拍的那位男子及他的水蛭的照片后,才写下了那篇文章。对于她称赞的某一处具体描述,我不得不承认,那并不是灵感顿生的神来之笔——只是在仔细观察相片并尝试了各种各样的比喻之后,我才定下了把水蛭描写为似带状物般的被放在瓶中央的比喻。

即便我只是随便手写一些文字,我几乎每次都会把相片库打开,或在面前放一些照片。如果我想描绘一个地方,我会打开那个地方的照片;如果我想描写一个人,我会打开那个人的照片。要是我自己的相片库不能满足我的需求,我就会去谷歌图片库这个“兔子洞”中搜索。

詹姆斯·伍德在《小说原理》一书中写道,照片会扼杀散文写作。“没有什么能比创造一个虚构人物更难。”论述人物描写的那一章开头写道,“我读过的那些以照片式描写开头的初出茅庐者写的小说数量之多,由此可得出这一结论。”通过实例,他一针见血地指出了这种照片式的写作手法。“你能认得出这种文风:‘在强烈的阳光下,母亲眯起了双眼,不知为什么手里紧攥着一只死了的野鸡……而父亲则显得从容自在,一如既往地无拘无束,头上还戴着那顶我孩童记忆中的布拉格绒毡帽。’”

伍德对这种文风的完美模仿以一个谴责结尾:“不成熟的小说家执著于静态描写,因为这比动态描写容易得多。”相比之下,堂·德里罗曾表示,一张张照片给予了他灵感,他的一些小说由此诞生。《坠落的人》来源于对一张同名照片的好奇,拍摄者是理查德·德鲁,照片中那个双塔袭击事件幸存者的形象令人难以忘怀。而《地下世界》的灵感则来自《纽约时报》上的并列标题:“我看到这两个标题,真的,就像看到一幅图似的。”德里罗说,“它们相互搭配的方式,每个标题下面是三栏铅字。”

有一整套写作练习是专注于照片的:挑选一张照片并从它的视觉内容中编写一个故事;提供一张照片并要求写作者用照片中的一个人或物品作为故事中的人物或道具。无论是虚构文学作家还是非虚构文学作家,都会用这一拐杖支撑他们颤颤巍巍地走过写作瓶颈或记忆缺失的困境。可能会扼杀小说文采的一张照片,也可能会给评论家的作品带来生气;有利于记者准确报道的一张照片,也可能会激发出诗人的奇思妙想。

无穷尽且廉价的数码摄像,把我们都变成了档案保管员。而且,如今如此普遍的拍照行为本身,正影响着我们记忆的方式。琳达·亨克尔的一项研究发现,拍照改变了我们体验世界的方式,而重温照片则改变了我们记忆这些体验的方式。在文章中,亨克尔把自己的发现与另外一项关于做笔记的研究联系起来:“有研究发现,与做笔记相比,温习课堂上所做的笔记能够更好地增强记忆。与其相似,如果我们能真正地重温照片并与之互动,而不仅仅是收集它们,那么照片也许亦能增强我们的记忆。”

看照片写作,似乎应该能产生同样的效果——使我们将体验和经历转化为语言的方式更为敏锐。我认为,照片不仅改变了我们写作的内容,也改变了我们写作的方式。自拍和自传的兴起同时发生,并不是偶然巧合。

拍照催生了一种新的“图说”方式,尤其作家本人就是摄像师时。这就是为什么我发现自己这么心甘情愿地放下笔记本,转而完全依赖我的相片库。与我试写的文字和笔记本的那几页纸相比,我的照片是更卓有成效的初稿,是更丰富的档案记录。就连这篇文章也是来源于“一批”的照片:琼·迪翁《向伯利恒匍匐》的书封面、几段具体段落的照片、朋友写来的一封邮件的截图、我写的关于水蛭收集者的文章、卖水蛭者的照片,以及詹姆斯·伍德《小说原理》中两个段落的照片。在写文字时,我一直在一个命名为“细碎收集者的细碎玩意儿窝”的相片库中翻阅上述照片,这个名字是从泰德·休斯的《文学生活》中借用的,名字本身就是工作中的作家的真实“快照”。