Distributed attitude synchronization using backstepping and sliding mode control

Johan THUNBERG,Wenjun SONG,Yiguang HONG,Xiaoming HU

1.KTH Royal Institute of Technology,S-100 44 Stockholm,Sweden;

2.Key Laboratory of Systems and Control,Academy of Mathematics and Systems Science,

Chinese Academy of Sciences,Beijing 100190,China

Distributed attitude synchronization using backstepping and sliding mode control

Johan THUNBERG1†,Wenjun SONG2,Yiguang HONG2,Xiaoming HU1

1.KTH Royal Institute of Technology,S-100 44 Stockholm,Sweden;

2.Key Laboratory of Systems and Control,Academy of Mathematics and Systems Science,

Chinese Academy of Sciences,Beijing 100190,China

We consider the problem of attitude synchronization for systems of rigid body agents with directed topologies.Two different scenarios for the rotation matrices of the agents are considered.In the first scenario,the rotations are contained in a convex subset of SO(3),which is a ball of radius less than π/2,whereas in the second scenario the agents are contained in a subset of SO(3),which is a ball of radius less than π.Using a control law based on backstepping and sliding mode control,we provide distributed,semi-global,torque control laws for the agents so that the rotations asymptotically synchronize.The control laws for the agents in the first scenario only depend on the relative rotations between neighboring agents,whereas the control laws in the second scenario depend on rotations defined in a global coordinate frame.Illustrative examples are provided where the synchronization is shown for both scenarios.

Attitude synchronization;Distributed control;Multi-agent systems

1 Introduction

We propose two distributed torque control laws for solving the attitude synchronization problem.In the problem at hand,a system of rigid bodies shall synchronize(or reach consensus in)their attitudes(rotations or orientations).A desirable property is also that the rotations asymptotically converge to some rotation matrix in a fixed world coordinate frame,i.e.,the angular velocities converge to zero.The problem is interesting since it has applications in the real world,e.g.,systems of satellites or unmanned aerial vehicles.It is challenging since the kinematics and dynamics are nonlinear.

In order to arrive at the final formulation of our dynamic torque control laws,we first formulate control laws on a kinematic level.These kinematic control lawsare designed in such a way that if the agents were to use them,meaning that the kinematic control laws can be tracked perfectly by the agents,the rotations would asymptotically reach consensus,and furthermore they would remain inside a specified ball in SO(3)containing the initial rotations,i.e.,the ball is invariant.

The aim for the torque control laws we present is to track the kinematic control laws in such a way that 1)the rotations will reach consensus and 2)the ball containing the rotations will still be invariant.The way we succeed with this task is by using a backstepping and sliding mode approach.

The kinematic control laws we use were originally provided in[1]in a slightly less general form.These control laws are in no way novel on their own,they have been used widely within the consensus literature with great success.They are essentially equivalent to the weighted average of the difference between the states of neighboring agents.Instead,the novelty lies in the domain of application.The authors showed that,under some additional constraints on the initial rotations,these standard control laws could be used in the attitude synchronization problem if the logarithmic representation is used for the rotations,also referred to as the axis-angle representation.

We consider two different kinematic control laws[1],which are provided for two different scenarios.In the first scenario the rotations are initially confined to be inside a geodesic convex ball in SO(3)(which essentially can be as large as half SO(3)in terms of measure)and the information used in the control law is based on the relative rotations between the agents.The problem of using relative rotations in order to reach attitude synchronization has been studied on a dynamic level in,for example,references [2]and[3].In the second scenario the rotations are initially confined to be inside a geodesic weakly convex ball in SO(3)see[4](which could be almost as large as SO(3)in terms of measure),and in this scenario absolute rotations are used,i.e.,rotations that are defined in some global coordinate reference frame.The problem of using absolute rotations has been studied in[5,6].

In this paper,building upon the kinematic control laws,we provide two torque control laws where each one is designed to track one of the kinematic control laws.This means that the first torque control law is designed so that the rotations reach consensus while the agents remain within a convex ball.Whereas the second control law is designed so that the agents reach consensus while remaining in a weakly convex set,which corresponds to a ball in SO(3)with radius less than π.

We have now made a distinction between the two different scenarios we consider in terms of the size of the feasible region(convex ball vs.weakly convex ball)and the type of information used(relative rotations defined in the body frames of the agents vs.absolute rotations in a global frame).Another distinction we make is on the type of interaction topology that is used.In the first scenario,where relative rotations are used,we assume a weak type of connectivity,namely that the interaction graph is quasi strongly connected,i.e.,it contains a(rooted)spanning tree.In the second scenario,where absolute rotations are used,we assume that the graph is strongly connected.

Comparing our second control law to the ones in[5,6],the connectivity graph between the agents are either balanced in[5]or undirected in[6],whereas our approach consider the case where the graph is strongly connected.Another limitation compared to our work is that the invariance of a convex ball cannot be guaranteed.This implies that the mapping between the group of rotation matrices and the unit quaternions(or modified Rodrigues parameters)is not one-to-one.Thus confusion might arise among the agents over which value is the correct one.

The paper proceeds in the following manner.In Section 2,we first introduce the(principal)logarithm of a rotation matrix,also referred to as the axis-angle representation.This is followed by the introduction of the kinematics and dynamics for a rotation matrix.As a last part of this section we introduce the attitude synchronization problem which is to be solved by the methods introduced in the subsequent sections.In Section 3,under some additional constraints on the rotations and the connectivity between the agents,we give the solution to the two synchronization problems in the form of two control laws in two theorems.In Section 4,some illustrative examples are provided.

2 Preliminaries and problem formulation

Consider a system ofnrigid body agents.We want to construct distributed torque control laws for the agents such that the rotations of the agents asymptotically synchronize,i.e.,the rotations converge to some common rotation.Henceforth,we assume that the agents are static with respect to their positions and only consider the rotational movement.

2.1 Rotations

We denote the world frame as FWand the instantaneous body frame of agentias Fi.The rotation of agentiin FWat timetis the rotation matrixRi(t)∈SO(3),whereas the rotation between agentiand agentjin Fiat timetis the rotation matrix

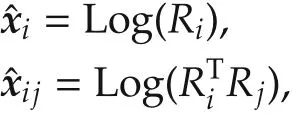

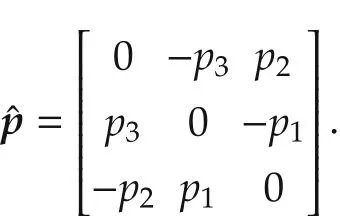

Letxi(t)andxij(t)denote the axis-angle representations of the rotationsRi(t)andRij(t),respectively.The axis-angle representation is obtained from the logarithmic map as

Therefore,this mapping between skew symmetric matrices and vectors in R3is linear and bijective.For any skew symmetric matrix there exists a corresponding rotation matrix,via the exponential map,however for each rotation matrix there exist infinitely many skew symmetric matrices that generate the rotation matrix via the exponential map.Due to this reason,in order to avoid ambiguities in the axis-angle representation we restrict the set of rotation matrices that we consider.

The mapping Log is defined as the principal logarithm.It is a mapping from the open ballBπ(I)with radius π in SO(3)to the set of skew symmetric matrices corresponding to vectors in the open ballBπ(0)with radius π in R3.Note here that in SO(3)the ballBπ(I)is defined with respect to the Riemannian metric(geodesic distance),whereas in R3the standard Euclidean metric is used.The setBπ(I)comprises almost all SO(3)and is defined as the largest weakly convex set in SO(3),see[4],so in practice this restriction is of limited importance.By imposing this restriction,Log becomes a local diffeomorphism,so under the assumptions the mapping to the axis-angle representation is smooth and bijective.For any proposed control law,we need to show thatBπ(I)is positively invariant in SO(3)which is equivalent to show thatBπ(0)is positively invariant in R3.We will come back to this invariance and the precise meaning of it.

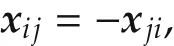

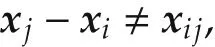

As an elementary property for the axis-angle repre-

sentation it follows that

and in general,

which can be seen from the Baker-Campbell-Hausdorff formula.

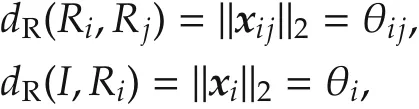

There is a close relationship between the Riemanninan distance between two elements in SO(3)and the axis-angle representation given as follows:

wheredRis the Riemanninan metric on SO(3)and θijand θiare short hand notation for ‖xij‖2and ‖xi‖2,respectively.This relationship can be used in order to show the invariance of the convex balls,when the control laws we define are used.

2.2 Equations of motion

We will in general suppress the time dependence for the variables.Let the instantaneous angular velocity of Fiwith respect to FWin the frame Fibe denoted as ωi.The kinematics ofRiandRijare given by

The corresponding equations forxiandxij(see[7])are given by

where the transition matrixLxiis given by

The function sinc(x)is defined so thatxsinc(x)=sinx,sinc(0)=1 andui=xi/θi.It was shown in[8],thatLθuis invertible for θ ∈ (−2π,2π).Hence we know that the matrix norm ofLθuis bounded onBπ(0).

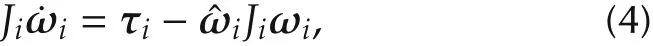

The dynamical equation is given by

where the matrixJi∈ R3×3is the constant positive definite and symmetric inertia matrix of agenti,and τi∈ R3is the control torque expressed in Fi.

2.3 Graph structure

To represent the connectivity between the agents,we introduce the directed connectivity or neighborhood graph G=(V,E).The setV={1,...,n}is the node set and the setEis the edge set.Agentihas a corresponding nodei∈V.Let Ni∈Vcomprise the neighbors of agenti.The directed edge fromjtoi,denoted as(j,i),belongs toEif and only ifj∈Ni.We assumei∈Ni.This neighborhood Niof agenticould either be based on estimation or communication and is to be clarified by the context.If estimation is used,the agents can observe their neighbors using,e.g.,vision,whereas if communication is used they receive information from their neighbors.

A directed path in G is a finite sequence of distinct nodes inV,where any two consecutive nodes in the sequence correspond to an edge inE.A nodeiis connected to a nodejif there is a directed path from nodejto nodei.

The graph G is quasi strongly connected if there is a node such that all other nodes are connected to it.The graph G is strongly connected if each node is connected to all other nodes.

2.4 Problem formulation

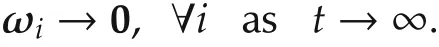

The overall problem is to find a torque control law for each agentiso that the rotations of all agents converge to some common rotation in the global frame FWas time goes to infinity,i.e.,

ast→∞.Equivalently in terms of the axis-angle representation

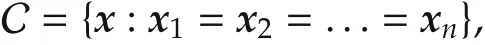

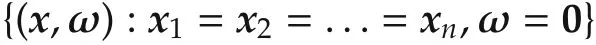

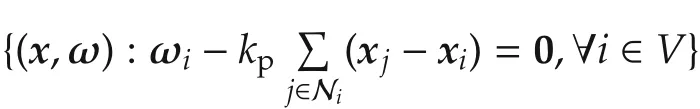

ast→ ∞.This should hold for all initial rotations in some specified region,and we might also say that the consensus set is attractive relative to this region.Under the assumption that the rotations are contained inBπ(I)for all times,this can be stated more formally as follows.We definex=(x1,...,xn)Tand the consensus set

which is attractive ifx(t)approaches C as the time goes to infinity.Hence,we want the set C to be(uniformly)attractive relative to some set contained inBπ(0).

We also require that the angular velocity ωishall converge to zero,i.e.,

A kinematic control law solving this problem is hereinafter referred to as a kinematic synchronization control law,whereas a dynamic control law solving this problem is referred to as a dynamic synchronization control law.

3 Proposed control laws

As mentioned in the introduction,solutions are provided for two different scenarios.The scenarios differ in what information is assumed to be known among the agents.In the first scenario(scenario 1),we assume that agenti∈Vpossesses the knowledge of the relative rotations between itself and its neighbors,i.e.,Rijwherej∈Ni.

In the second scenario(scenario 2),we assume that agenti∈Vpossesses the knowledge ofRjforj∈Ni.Note that the knowledge in scenario 2 is stronger in the sense thatRijcan be constructed fromRiandRjbut not vise versa,hence the knowledge in scenario 1 is a subset of the knowledge in scenario 2.

The reason for considering the two different scenarios stems from the fact that the absolute rotationsRiare not always possible to measure.Suppose in a real world application,that the agents are equipped with cameras,and that they are observing each other or the surroundings.If the agents are observing each other with no common reference object,only the relative rotations are possible to retrieve,scenario 1.On the other hand,if the agents are observing some common object attached with a global frame of reference,the absolute rotations are possible to retrieve,scenario 2.

We will continue by first providing the kinematic synchronization control laws.These control laws were originally provided in[1]in slightly less general forms.

3.1 Kinematic control laws

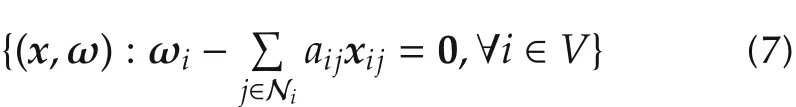

The kinematic controllers are given by where aij>0 and we claim that under the right circumstances(5)and(6)are kinematic synchronization control laws for scenario 1 and scenario 2,respectively.These circumstances are clarified in the following two propositions,which are provided without proofs.

Proposition 1Suppose G is quasi strongly connected.If there is a Q∈SO(3),such that the rotations of the agents initially are contained within a closed ball(Q)of radius r less than π/2 centered around Q,then the set of control laws defined in(5)are kinematic synchronization control laws and C is uniformly asymptotically stable relative to(Q).Furthermore,the set(Q)is(positively)invariant.

Proposition 2If the rotations of the agents initially are contained in a closed ball(I)of radius r less than π in SO(3),and the graph G is strongly connected,then the set of control laws defined in(6)are kinematic synchronization control laws and C is uniformly attractive relative to(I).Furthermore,the set(I)is(positively)invariant.

When we say that a closed ball is positively invariant,we mean it in the sense that if each rotation in the system is contained in(Q)at time t0,the rotation will be contained in(Q)for all times t∈[t0,∞).

Wenote that in Proposition 1, the radius of the ball can be almost π/2,namely that the local region for which the controller is guaranteed to work is essentially almost half of SO(3),whereas in Proposition 2,the radius of the ball can be almost π,which is almost SO(3).In Proposition 2 the region of convergence is larger in Proposition 1.What we mean by asymptotic stability in this context is that the set is stable and attractive.

Let us now in the following two subsections,proceed with the introduction of the dynamic control laws.

3.2 Dynamic control law in scenario 1

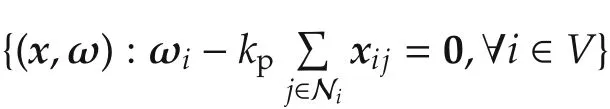

An implication of Proposition 1 is that if we can construct a torque control law τifor each agent i such that x and ω =(ω1,...,ωn)Tconverge to the set

at some finite time t1≥ t0and Ri(t) ∈ Bπ/2(Q)∀i,t∈[t0,t1],then our torque is a dynamic synchronization control law.The aim of this subsection is to find such a torque τi.We will use the methods of back stepping and sliding mode control in order to achieve this.Except for Rij(or xij),we assume that agent i is able to obtain its angular velocity ωiand the relative angular ve locity ωij=Rijωj− ωibetween itself and all agents j in the set Ni.This implies that it can measure ωj,sinceCommon for these rotations and velocities is that(by the use of proper sensors)they can be measured directly by agent i and there is no need for communication between the agents.

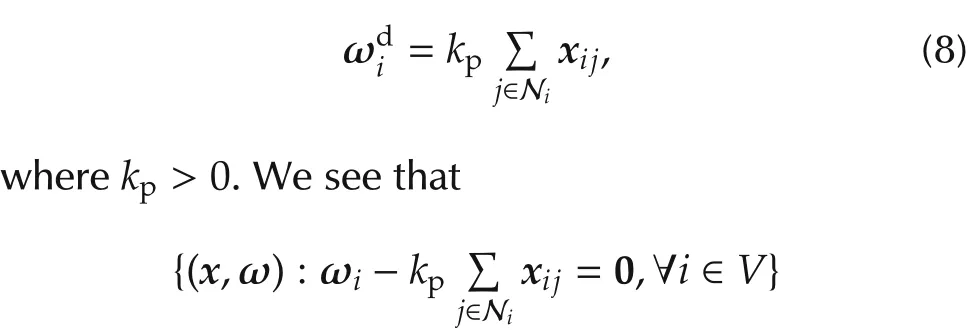

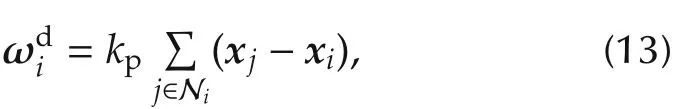

Let us define the desired angular velocity for agent i as

is an example of a set on the form(7)with aij=kpfor all j∈Ni.Let us proceed by defining the error between the desired angular velocity and the angular velocity as

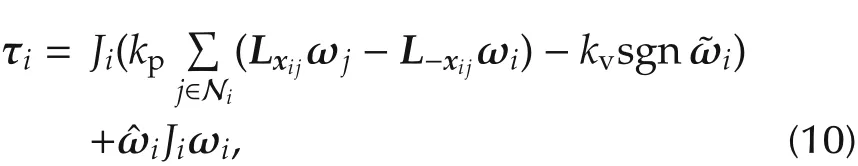

where kp>0,kv>0 and the sign function in this context returns a vector with the component wise sign of its argument.Under the assumption that the norm of the error(t0)is bounded,the following lemma assures that there are kpand kvsuch that τican be chosen as a synchronization control law.The proof is based on back stepping.

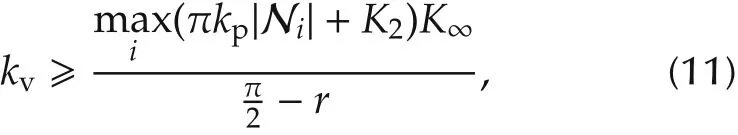

Assume that the agents use the torque control law(10)and initially are contained in an open ball Br(Q)of radius r< π/2 around some Q in SO(3)and assume‖ω˜i(t0)‖2<K2∈R+and‖ω˜i(t0)‖∞<K∞∈R+for all i∈V.If the controller gains are chosen so that

where|Ni|denotes the number of neighbors of agent i,then ω will reach the set

and stay there before the rotation of any agent leavesBπ/2(Q).

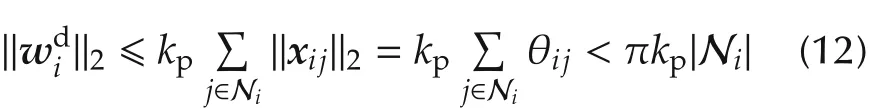

ProofAssume without loss of generality thatQ=I.The setsBπ/2(I)andBr(I)are geodesically convex on SO(3)andBr(I)⊂Bπ/2(I).Thus at timet0,we have

Assume there exists a timet1>t0,such that all the agents stay inBπ/2(I)whent∈ [t0,t1].Then,in this time interval we have

by(8).The inequality θij≤ θi+ θjis used in(12),since θijis the geodesic distance betweenRiandRjon SO(3).

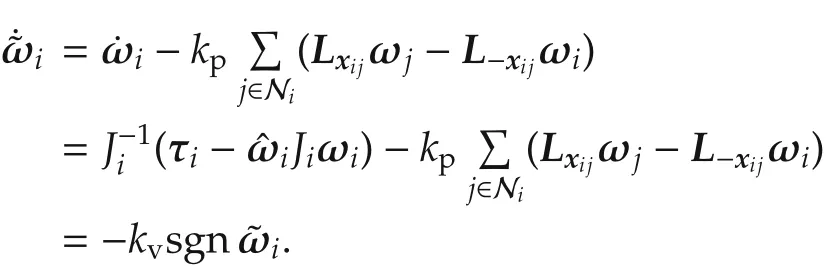

Now,let us consider the dynamics ofBy(1),(3)and(9),we have that

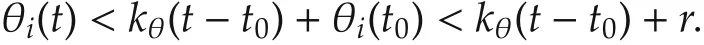

Letkθ=miax(πkp|Ni|+K2),then for the solution to θiint∈[t0,t1)it holds that

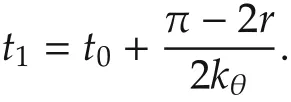

From this,it follows thatt1can be chosen as

By(2),(4),and(8)–(10),we consider the dynamics of ˜ωi:

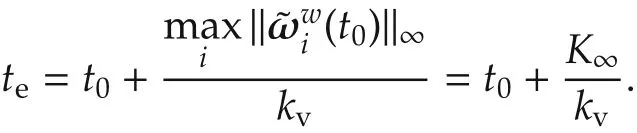

It follows that the angular velocities of all agents will reach the corresponding sliding manifold at time

Thus,our conclusions follows ifte≤t1.

By using the results in Lemma 1 we are now ready to pose the main theorem of this subsection.

Theorem 1Suppose G is quasi strongly connected.If the agents use controller(10)and initially are contained in an open ballBr(Q)of radiusr< π/2 around someQin SO(3),K∞∈R+and the controller gainskv,kpare chosen such that(11)is satisfied, then the controller (10) is a dynamic synchronization control law.

ProofLemma 1 guarantees that there exists atesuch that ωi(t)=whent≥te,andRi(t)∈Bπ/2(Q)whent∈[t0,te].Since there is a finite amount of agents,there exists a closed ball(Q)containing the agents at timete,wherer′< π/2.Then,according to Proposition 1(wheret0=te)the rotations of the agents will be synchronized.

One interesting thing to notice is that the condition that the rotations of the agents must be contained in a convex ball is only a sufficient condition for synchronization.It is easy to construct examples where the controller fails for a ballBr(Q)of radiusr≥ π/2.However,it is also possible to construct examples where it works.Therefore,a radius ofr< π/2 is a necessary and sufficient condition in order to guarantee synchronization for every set of initial rotations of the agents insideBr(Q).The set

is not only uniformly attractive but uniformly asymptotically stable.This can be seen by using the reduction results for set stability in[9].

3.3 Dynamic control law in scenario 2

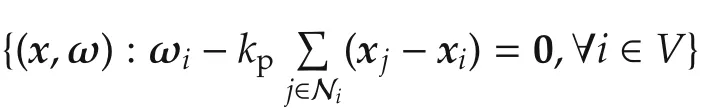

Similar to scenario 1,we note that if we can construct a torque control law for each agent so that(x,ω)converges to the set

at some finite timet1≥t0andRi(t)∈(Q),for alli,t∈[t0,t1],then the torque is a dynamic synchronization control law.This subsection will proceed with a way of finding such a control law.In this scenario,we assume that agentiis able to obtainxjand ωjfor all agentsjthat are contained in Ni.

Now we proceed completely analogously to scenario1,by defining the desired angular velocity for agentias

wherekp>0.Then we define the error between the desired angular velocity and the actual velocity as

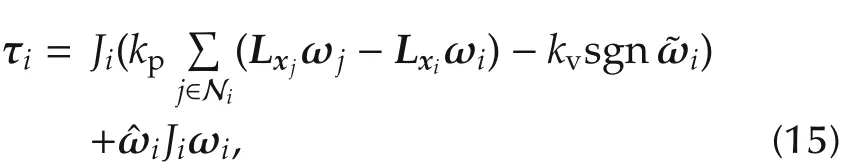

Given the definition above,we claim that the following torque control law is a synchronization control law.

wherekp>0 andkv>0.

Lemma 2Assume that the agents use controller(15)and initially are contained in the open ballBr(I)of radiusr< π,and assumeIf the controller gains are chosen such that

where|Ni|denotes the number of neighbors that agentihas,then ω will reach the set

before any agentileavesBπ(Q),i=1,...,n.

ProofThe proof is analogous to the proof of Lemma 1 and hence omitted.

Theorem 2Suppose that G is strongly connected.If the rotations of the agents initially are contained in an open ballBr(I)of radiusr< π in SO(3),and the controller gainskvandkpare chosen such that(16)is satisfied,then the controller(15)is a dynamic synchronization controller.

ProofThe proof is analogous to the proof of Theorem 1 and is omitted.

4 Illustrative examples

We will now illustrate the convergence of the rotations for the two different control laws in two examples.The simulations were conducted in Matlab. The moment of inertial matrixJiwas given as

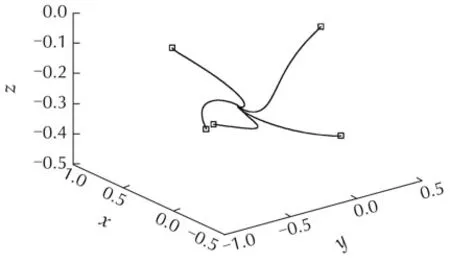

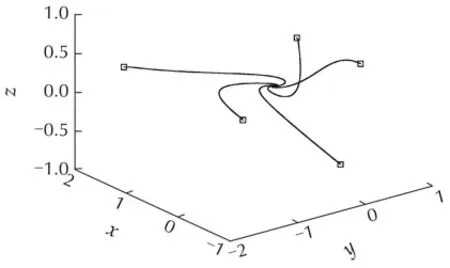

for each agenti.In Fig.1,the control law(10)for scenario 1 is used,and in Fig.2,the control law(15)for scenario 2 is used.One can see how the rotations of the agents converge from their initial rotations to the final rotation where they reach synchronization.Observe that the rotations are represented in axis-angle representation as a vectors in R3.

Fig.1 The agents use controllers(10)and their rotations converge to a synchronized rotation as time goes to infinity.Boxes denote the initial rotations of the agents.In this example,the initial rotations of the agents are uniformly distributed in the geodesic ball Br(I)with r=1.2,the controller parameters are chosen as kp=1 and kv=11.2,the edge set of the topology is E={(3,1),(1,2),(2,3),(3,4),(4,5)}and the time horizon is 10s.

Fig.2 The agents use controllers(15)and their rotations converge to a synchronized rotation as time goes to infinity.Boxes denote the initial rotations of the agents.In this example,the initial orientations of the agents are uniformly distributed in the geodesic ball Br(I)with r=2.5,the controller parameters are chosen as kp=1 and kv=31.7,the edge set of the topology is E={(5,1),(1,2),(2,3),(3,4),(4,5)}and the time horizon is 10s.

[1]J.Thunberg,W.Song,X.Hu.Distributed attitude synchronization control of multi-agent systems with directed topologies.Proceedings of the 10th World Congress on Intelligent Control and Automation.Beijing:IEEE,2012:958–963.

[2]A.Sarlette,R.Sepulchre,N.E.Leonard.Autonomous rigid body attitude synchronization.Automatica,2009,45(2):572–577.

[3]W.Ren.Distributed cooperative attitude synchronization and tracking for multiple rigid bodies.IEEE Transactions on ControlSystems Technology,2010,18(2):383–392.

[4]R.Hartley,J.Trumpf,Y.Da.Rotation averaging and weak convexity.Proceedings of the 19th International Symposium on Mathematical Theory of Networks and Systems.Budapest:MTNS,2010:2435–2442.

[5]K.D.Listmann,C.A.Woolsey,J.Adamy.Passivity-based coordination of multi-agent systems:a backstepping approach.Proceedings of the European Control Conference.Budapest:IEEE,2009:2450–2455.

[6]D.V.Dimarogonas,P.Tsiotras,K.J.Kyriakopoulos.Laplacian cooperative attitude control of multiple rigid bodies.Proceedings of the IEEE International Symposium on Intelligent Control.Munich:IEEE,2006:3064–3069.

[7]W.Song,J.Thunberg,Y.Hong,et al.Distributed attitude synchronization control of multi-agent systems with time-varying topologies.Proceedings of the 10th World Congress on Intelligent Control and Automation.Beijing:IEEE,2012:946–951.

[8]E.Malis,F.Chaumette,S.Boudet.2-1/2-D visual servoing.IEEE Transactions on Robotics and Automation,1999,15(2):238–250.

[9]M.El-Hawwary,M.Maggiore.Reduction theorems for stability of closed sets with application to backstepping control design.Automatica,2013,49(1):214–222.

10 June 2013;revised 25 November 2013;accepted 25 November 2013

DOI10.1007/s11768-014-0094-1

†Corresponding author.

E-mail:johan.thunberg@math.kth.se.Tel.:+46 8 790 66 59.

The research of J.Thunberg and X.Hu was supported by the Swedish National Space Technology Research Programme(NRFP)and the Swedish Research Council(VR).

Johan THUNBERGreceived his M.S.degree in Engineering Physics from the Royal Institute of Technology(KTH)in Stockholm,Sweden.After that,he has worked as a research assistant at the Swedish Defence Research agency(FOI).Currently,he is a graduate student in Applied Mathematics at the Royal Institute of Technology(KTH)in Stockholm,and is funded by the Swedish National Space Technology Research Programme(NRFP)and the Swedish Research Council(VR).E-mail:johan.thunberg@math.kth.se.

Wenjun SONGis a Ph.D.candidate majoring in Complex System and Control at Academy of Mathematics and Systems Science,Chinese Academy of Sciences.She received her B.E.degree in Automation from Huazhong University of Science and Technology,Wuhan,China,in 2009.Her research interests include attitude control for rigid bodies and multi-agent systems.E-mail:jsongwen@amss.ac.cn.

Yiguang HONGreceived his B.S.and M.S.degrees from Department of Mechanics,Peking University,China,and his Ph.D.degree from Chinese Academy of Sciences(CAS).He is currently a professor in Academy of Mathematics and Systems Science,CAS.His research interests include nonlinear dynamics and control,multi-agent systems,distributed optimization,and reliability of software and communication systems.E-mail:yghong@iss.ac.cn.

Xiaoming Hureceived his B.S.degree from the University of Science and Technology of China in 1983,and M.S.and Ph.D.degrees from the Arizona State University in 1986 and 1989,respectively.He served as a research assistant at the Institute of Automation,the Chinese Academy of Sciences,from 1983 to 1984.From 1989 to 1990,he was a Gustafsson postdoctoral fellow at the Royal Institute of Technology,Stockholm,where he is currently a professor of Optimization and Systems Theory.His main research interests are in nonlinear control systems,nonlinear observer design,sensing and active perception,motion planning,control of multi-agent systems,and mobile manipulation.E-mail:hu@math.kth.se.

Control Theory and Technology2014年1期

Control Theory and Technology2014年1期

- Control Theory and Technology的其它文章

- Constrained optimal steady-state control for isolated traffic intersections

- Design of high-speed and low-power finite-word-length PID controllers

- Capture condition for endo-atmospheric interceptors steered by ALCS and ARCS

- Non-Zenoness of piecewise affine dynamical systems and affine complementarity systems with inputs

- Frequency-domain L2-stability conditions for time-varying linear and nonlinear MIMO systems

- Control of a flexible rotor active magnetic bearing test rig:a characteristic model based all-coefficient adaptive control approach