Effects of probiotic therapy on hepatic encephalopathy in patients with liver cirrhosis: an updated meta-analysis of six randomized controlled trials

Jun Xu, Rui Ma, Li-Feng Chen, Li-Jun Zhao, Kan Chen and Ren-Bing Zhang

Hangzhou, China

Effects of probiotic therapy on hepatic encephalopathy in patients with liver cirrhosis: an updated meta-analysis of six randomized controlled trials

Jun Xu, Rui Ma, Li-Feng Chen, Li-Jun Zhao, Kan Chen and Ren-Bing Zhang

Hangzhou, China

BACKGROUND:Liver cirrhotic patients with hepatic encephalopathy have poor prognosis. Probiotics alter the intestinal microbiota and reduce the production of ammonia. We conducted a meta-analysis about the role of probiotics on liver cirrhotic patients with hepatic encephalopathy.

DATA SOURCES:We collected the relevant literatures up to February 21, 2014 from databases of PubMed, EMBASE and the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials. A statistical analysis was conducted by RevMan 5.2 and STATA 12.0 software.RESULTS:Six randomized controlled trials involving 496 liver cirrhotic patients were included. The results showed that probiotic therapy significantly reduced the development of overt hepatic encephalopathy (OR [95% CI]: 0.42 [0.26, 0.70],P=0.0007). However, probiotics did not affect mortality, levels of serum ammonia and constipation (mortality: OR [95% CI]: 0.73 [0.38, 1.41],P=0.35; serum ammonia: WMD [95% CI]: -3.67 [-15.71, 8.37],P=0.55; constipation: OR [95% CI]: 0.67 [0.29, 1.56],P=0.35).

CONCLUSION:Probiotics decrease overt hepatic encephalopathy in patients with liver cirrhosis.

(Hepatobiliary Pancreat Dis Int 2014;13:354-360)

probiotics;

hepatic encephalopathy;

liver cirrhosis;

ammonia;

meta-analysis

Introduction

Hepatic encephalopathy (HE) is a serious disorder in patients with cirrhosis. HE has a variety of clinical manifestations ranging from cognitive alteration to coma and even death.[1]Overt HE is estimated to occur in 30%-45% of patients with cirrhosis.[2-4]The severity and frequency of such episodes are related to the increased risk of death.[5]Reported studies[6-8]showed that bowel movement disorders exist in liver cirrhotic patients, which may delay orocecal transit time, enhance the growth of pathogenic bacteria and the absorption of gut toxins. All of these trigger or aggravate HE.

Although the etiology and pathogenesis of HE are complicated, ammonia plays a vital role. Ammonia is released into the portal vein after the absorption by intestinal epithelium, and the ammonia is converted into urea by the liver. Then urea is excreted through urine.[9]Intestinal flora produces toxins such as benzodiazepine-like substances and mercaptans, which may aggravate the development of HE by increasing the toxicity of ammonia.[9,10]

A number of controlled studies on the therapeutic efficacy of probiotics for HE were well documented. One systematic review summarized that the probiotics or synbiotics were effective on HE in liver cirrhotic patients.[11]However, another review[12]did not demonstrate the obvious benefits to the outcomes of the liver cirrotic patients with HE. The present review included four more newlypublished randomized controlled trials (RCTs).[13-16]We aimed to assess the effect of probiotic therapies on HE in liver cirrhotic patients.

Methods

Literature search

We searched and collected the relevant literature between January 1, 1990 and February 21, 2014 from databases of PubMed, EMBASE and the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials. The key words used in search were probiotics, synbiotics, prebiotics, and lactulose. These terms were combined with one of the following medical headings during the search, which are hepatic encephalopathy, liver cirrhosis and liver diseases.

Criteria for inclusion and exclusion

The inclusion criteria: (i) treatment comparisons were made of outcomes between probiotics and controls which included no therapy or placebo; (ii) at least one of the outcomes mentioned below was included; (iii) if the studies were from the same institution and/or authors, the patients must be different; and (iv) for dual (or multiple) publications from the same institution and/or authors, either the one of higher quality or the latest publication was included.

The following studies or data were excluded: (i) the outcomes and parameters of patients were not clearly reported; (ii) it is impossible to extract the appropriate data from the published results; (iii) there is overlap between authors or centers in the published literature; and (iv) no comparison between probiotic and placebo/ no intervention.

Outcomes of interest and data extraction

We mainly aimed at evaluating the efficacy of probiotics on HE in patients with liver cirrhosis. We assessed the effects of probiotics on clinical indicators, such as serum ammonia, development of overt HE, mortality and constipation.

Two reviewers (XJ and MR) independently extracted the following parameters from each study: 1) first author and year of publication; 2) study population characteristics; 3) number of subjects who were included in studies, 4) clinical indicators included. All relevant text, tables and figures were reviewed for data extraction. Discrepancies between the two reviewers were resolved by discussion and consensus.

Qualitative assessment

Two reviewers identified studies independently by Jadad score table.[17,18]In this table, randomization scores 2 points, blinding scores 2 points, and description of withdrawals scores 1 point.

The meta-analysis was performed using the RevMan software, (version 5.2, Cochrane collaboration, http:// ims. cochrane.org/revman/download) and STATA (version 12.0, Stata Corp, College Station, TX, USA). We analyzed dichotomous variables using estimation of odds ratio (OR) with 95% confidence interval (CI). The pooled effect was calculated using either a fixed-effects or a random-effects model. The outcomes of the combined trials were tested using both the Chi-square test and heterogeneityI2test with substantial heterogeneity defined as greater than 50%. Effect size estimates were analyzed using fixedeffects models if the data were homogeneous. Otherwise random-effects models were used. Funnel plots with Egger's test and Begg's test were used to evaluate the publication bias. If plots were asymmetrical, then trim and fill analyses were performed to evaluate the stability of overall effects. APvalue <0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Literature search

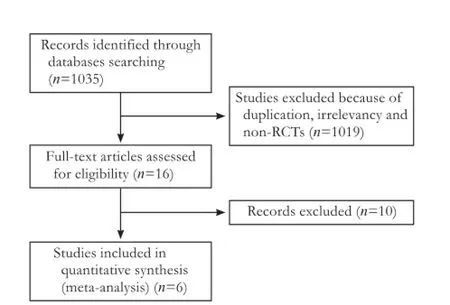

Among the 1035 relevant trials identified, 1019 were excluded because of duplication, irrelevancy and non-RCTs. Sixteen eligible trials were left. Of these, 10 were excluded as experiment group containing prebiotics, lactulose and synbiotics or control group is not placebo or no therapy group. Six trials were included in this meta-analysis (Fig. 1).

Funnel plots suggested that no publication bias was found in mortality (Egger's testP=0.086, Begg's testP=0.308) (Fig. 2A), overt HE (Egger's testP=0.123,Begg's testP=0.089) (Fig. 2B), and constipation (Egger's testP=0.561, Begg's testP=1.000) (Fig. 2C).

Fig. 1.Flow chart of literature search strategies.

Study characteristics and quality assessment

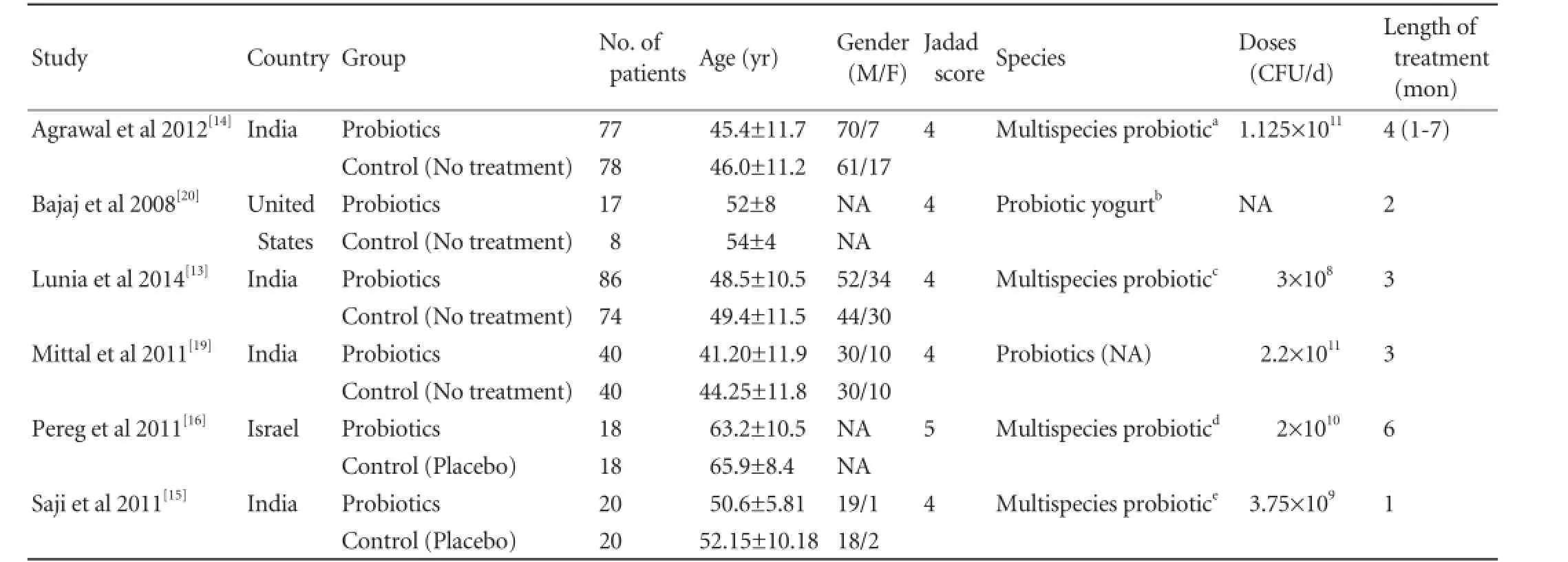

The characteristics of these 6 studies are summarized in Table. The 6 studies are all RCTs including a total of 496 patients: 258 in the probiotics group and 238 in the control group. Four studies were from India,[13-15,19]one from United States,[20]and one from Israel.[16]The sample size of each study varied from 25 to 160 patients.

Patients in the 6 studies were matched for age,[13-16,19,20]gender,[13-15,19]levels of serum ammonia,[13,14,16,19]overt HE development,[13,14,19,20]mortality,[13,14,19,20]and constipation.[13-15]

还有学者对语言迁移中文化负迁移现象的分析中,论证了文化负迁移现象对外语交际的影响,以及通过对文化负迁移的认识避免文化差异对语言交际的干扰。影响母语迁移不仅有文化因素,还有社会因素。

One trial scored 5 points, and other 5 trials scored 4 points according to Jadad score table (Table).

The level of serum ammonia

Five RCTs[13,14,16,19,20]analyzed the effect of probiotics on levels of serum ammonia in liver cirrhotic patients compared with placebo or no treatment. Probiotics had no significant effect on serum ammonia (WMD [95% CI]: -3.67 [-15.71, 8.37],P=0.55). However, the included studies on serum ammonia were heterogeneous (χ2=39.87, df=4,P<0.00001,I2=90%) (Fig. 3). We conducted a subanalysis of patients on arterial and venous ammonia and found that probiotics tend to reduce the arterial ammonia levels. However, this effect was not pronounced in venous ammonia. When the data of ammonia in the study of Pereg 2011 (not signed as arterial ammonia or venous ammonia) were excluded from arterial subgroup to venous subgroup, there was no heterogeneity of serum ammonia levels (I2=67.0% vs 0%).

Fig. 2.Funnel plot suggested that no statistically publication bias existed in mortality (A), overt HE (B) and constipation (C).

Table.Characteristics of included trials

Overt HE development

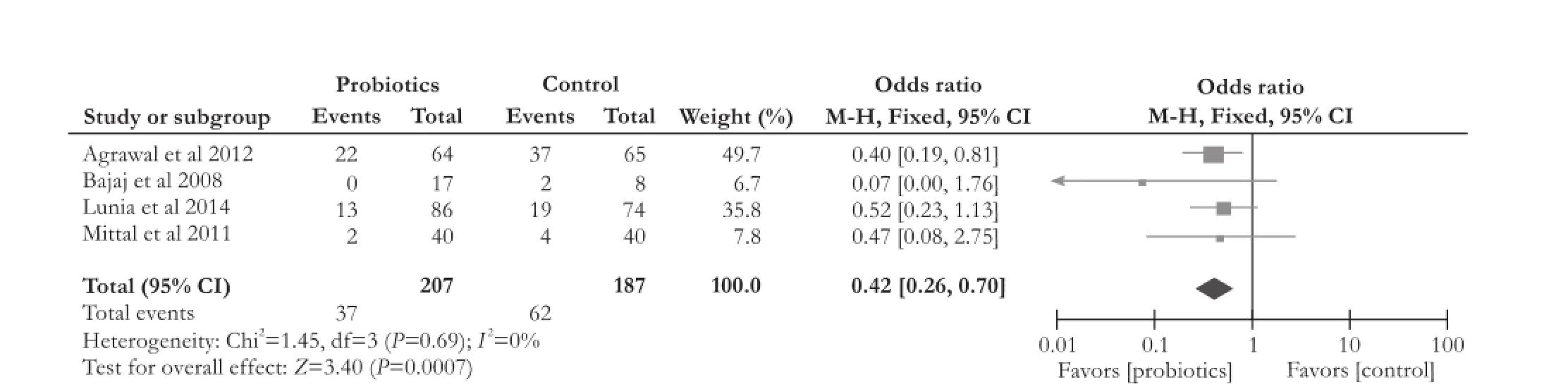

Four RCTs[13,14,19,20]compared the effect of probiotics with placebo on overt HE development. The data showed that probiotics significantly reduced overt HE development (OR [95% CI]: 0.42 [0.26, 0.70],P=0.0007). The included studies on overt HE development had no significant heterogeneity (χ2=1.45, df=3,P=0.69,I2=0%) (Fig. 4).

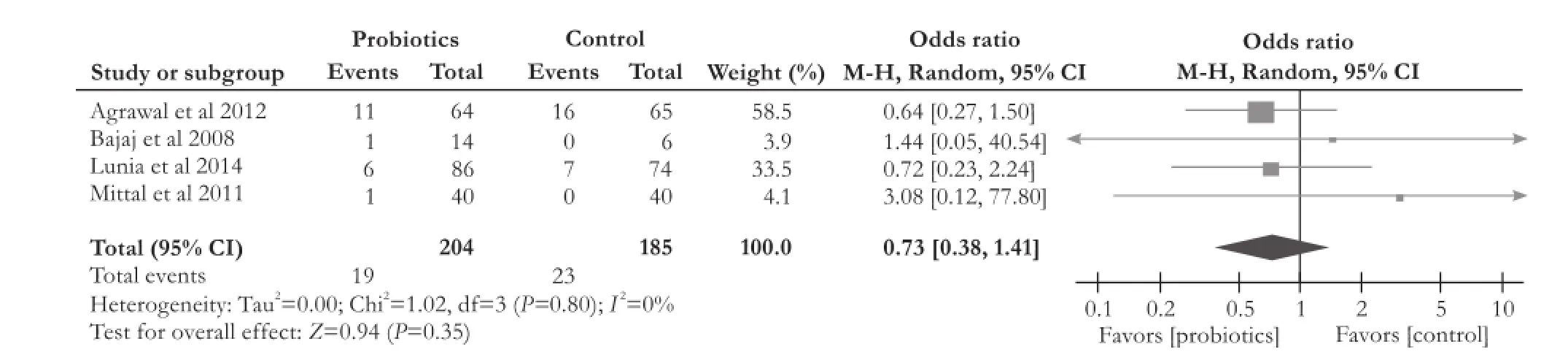

Mortality

All of the four RCTs[13,14,19,20]did not find a significant difference in mortality between the probiotics group and control group (OR [95% CI]: 0.73 [0.38, 1.41],P=0.35). We did not observe heterogeneity among thestudies (χ2=1.02, df=3,P=0.80,I2=0%) (Fig. 5).

Fig. 3.Forest plot displaying the results of the meta-analysis on levels of serum ammonia.

Fig. 4.Forest plot displaying the results of the meta-analysis on overt hepatic encephalopathy development.

Fig. 5.Forest plot displaying the results of the meta-analysis on mortality.

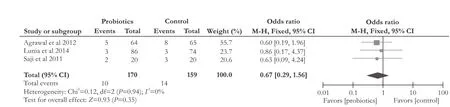

Fig. 6.Forest plot displaying the results of the meta-analysis on constipation.

Constipation

Three RCTs[13-15]compared the effect of probiotics with placebo on constipation in liver cirrhotic patients. There was no significant difference (OR [95% CI]: 0.67 [0.29, 1.56],P=0.35). The included studies on constipation were not heterogeneous (χ2=0.12, df=2,P=0.94,I2=0%) (Fig. 6).

Discussion

As a serious complication of advanced liver diseases, HE occurs in about 30%-45% of patients with liver cirrhosis, 10%-50% with a transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt[21-24]and 25%-80% with minimal HE without overt HE. Minimal HE has the risk of progression to overt HE.[4,25,26]

Probiotics inhibits the growth of pathogenic bacteria through acidifying the gut lumen, competing for nutrients, and producing antibacterial substances.[27,28]It has been shown that the administration of probiotics to liver cirrhotic patients resulted in a modulation of the gut flora with a significant reduction of the quantity of several bacterial pathogens in fecal bacteriological analysis.[28]

The data regarding the effects of probiotics has raised the possibility that they may be beneficial in the prevention and treatment of the complications of liver cirrhosis. Probiotics alter the gut flora and decrease the ammonia production. It has been shown that 30-day administration of probiotic bacteria to liver cirrhotic patients with minimal HE results in 50% reversal of encephalopathy.[28]Another study assessed the efficacy of a 3-month administration ofBifidobacterium longumplus fructo-oligosaccharides in 60 liver cirrhotic patients with minimal HE, and found that this combination significantly improved the results of biochemical and neuropsychological tests in minimal HE.[29]

This analysis also demonstrated that probiotics therapy significantly reduced the number of development of overt HE in patients with cirrhosis (OR [95% CI]: 0.42 [0.26, 0.70],P=0.0007). However, probiotics did not improve mortality, levels of serum ammonia and constipation (mortality: OR [95% CI]: 0.73 [0.38, 1.41],P=0.35; serum ammonia: WMD [95% CI]: -3.67 [-15.71, 8.37],P=0.55); constipation: OR [95% CI]: 0.67 [0.29, 1.56],P=0.35).

Three RCTs studies[13,14,16]showed that probiotics reduced serum ammonia, while two RCTs[19,20]did not. Our meta-analysis combined with the five studies found that although probiotics tend to reduce ammonia, the difference was not statistically significant. Some RCTs[16,30,31]showed that probiotics reduces serum levels of bilirubin and alanine aminotransferase and improves the Child-Pugh functional class, which may contribute to the prevention of overt HE development.

The levels of serum ammonia of our meta-analysis were heterogeneous (χ2=39.87, df=4,P<0.00001,I2=90%), so we used a random-effects model to analyze the data. To partially address this limitation, we conducted a sub-analysis of patients with arterial and venous ammonia. It is true that, in the arterial subgroup, theadministration of probiotics had a trend to reduce the ammonia levels. However, this effect diminished as far as venous ammonia is concerned. When we excluded the data of ammonia in the study of Pereg 2011[16](not signed as arterial ammonia or venous ammonia) from the arterial group to the venous subgroup, the subgroup heterogeneity of serum ammonia levels was none (I2=67.0% vs 0%). It seemed that the existence of the heterogeneity of serum ammonia may be due to the relatively limited studies providing the data of venous ammonia levels. Nevertheless, this study is, to our knowledge, the first meta-analysis to examine the role of probiotics in patients with liver cirrhosis by comparing probiotics and placebo/no treatment.

In conclusion, the results of this meta-analysis of 496 patients showed that probiotics are effective in preventing overt HE development in patients with liver cirrhosis.

Contributors:XJ and MR contributed equally to the article. ZRB proposed the study. XJ and MR performed research and wrote the first draft. CLF, ZLJ and CK collected and analyzed the data. ZRB revised the manuscript. All authors contributed to the design and interpretation of the study and to further drafts. ZRB is the guarantor.

Funding:The study was supported by a grant from the Educational Commission of Zhejiang Province, China (Y201328900).

Ethical approval:Not needed.

Competing interest:No benefits in any form have been received or will be received from a commercial party related directly or indirectly to the subject of this article.

1 Ferenci P, Lockwood A, Mullen K, Tarter R, Weissenborn K, Blei AT. Hepatic encephalopathy--definition, nomenclature, diagnosis, and quantification: final report of the working party at the 11th World Congresses of Gastroenterology, Vienna, 1998. Hepatology 2002;35:716-721.

2 Eroglu Y, Byrne WJ. Hepatic encephalopathy. Emerg Med Clin North Am 2009;27:401-414.

3 Poordad FF. Review article: the burden of hepatic encephalopathy. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2007;25:3-9.

4 D'Amico G, Garcia-Tsao G, Pagliaro L. Natural history and prognostic indicators of survival in cirrhosis: a systematic review of 118 studies. J Hepatol 2006;44:217-231.

5 Rahimi RS, Rockey DC. Complications of cirrhosis. Curr Opin Gastroenterol 2012;28:223-229.

6 Gupta A, Dhiman RK, Kumari S, Rana S, Agarwal R, Duseja A, et al. Role of small intestinal bacterial overgrowth and delayed gastrointestinal transit time in cirrhotic patients with minimal hepatic encephalopathy. J Hepatol 2010;53:849-855.

7 Pande C, Kumar A, Sarin SK. Small-intestinal bacterial overgrowth in cirrhosis is related to the severity of liver disease. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2009;29:1273-1281.

8 Bauer TM, Schwacha H, Steinbrückner B, Brinkmann FE, Ditzen AK, Aponte JJ, et al. Small intestinal bacterial overgrowth in human cirrhosis is associated with systemic endotoxemia. Am J Gastroenterol 2002;97:2364-2370.

9 Solga SF. Probiotics can treat hepatic encephalopathy. Med Hypotheses 2003;61:307-313.

10 Wright G, Chattree A, Jalan R. Management of hepatic encephalopathy. Int J Hepatol 2011;2011:841407.

11 Holte K, Krag A, Gluud LL. Systematic review and metaanalysis of randomized trials on probiotics for hepatic encephalopathy. Hepatol Res 2012;42:1008-1015.

12 McGee RG, Bakens A, Wiley K, Riordan SM, Webster AC. Probiotics for patients with hepatic encephalopathy. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2012;9:CD008716.

13 Lunia MK, Sharma BC, Sharma P, Sachdeva S, Srivastava S. Probiotics prevent hepatic encephalopathy in patients with cirrhosis: a randomized controlled trial. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2014;12:1003-1008.

14 Agrawal A, Sharma BC, Sharma P, Sarin SK. Secondary prophylaxis of hepatic encephalopathy in cirrhosis: an openlabel, randomized controlled trial of lactulose, probiotics, and no therapy. Am J Gastroenterol 2012;107:1043-1050.

15 Saji S, Kumar S, Thomas V. A randomized double blind placebo controlled trial of probiotics in minimal hepatic encephalopathy. Trop Gastroenterol 2011;32:128-132.

16 Pereg D, Kotliroff A, Gadoth N, Hadary R, Lishner M, Kitay-Cohen Y. Probiotics for patients with compensated liver cirrhosis: a double-blind placebo-controlled study. Nutrition 2011;27:177-181.

17 Jadad AR, Moore RA, Carroll D, Jenkinson C, Reynolds DJ, Gavaghan DJ, et al. Assessing the quality of reports of randomized clinical trials: is blinding necessary? Control Clin Trials 1996;17:1-12.

18 Olivo SA, Macedo LG, Gadotti IC, Fuentes J, Stanton T, Magee DJ. Scales to assess the quality of randomized controlled trials: a systematic review. Phys Ther 2008;88:156-175.

19 Mittal VV, Sharma BC, Sharma P, Sarin SK. A randomized controlled trial comparing lactulose, probiotics, and L-ornithine L-aspartate in treatment of minimal hepatic encephalopathy. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol 2011;23:725-732.

20 Bajaj JS, Saeian K, Christensen KM, Hafeezullah M, Varma RR, Franco J, et al. Probiotic yogurt for the treatment of minimal hepatic encephalopathy. Am J Gastroenterol 2008;103:1707-1715.

21 Amodio P, Del Piccolo F, Pettenò E, Mapelli D, Angeli P, Iemmolo R, et al. Prevalence and prognostic value of quantified electroencephalogram (EEG) alterations in cirrhotic patients. J Hepatol 2001;35:37-45.

22 Saxena N, Bhatia M, Joshi YK, Garg PK, Dwivedi SN, Tandon RK. Electrophysiological and neuropsychological tests for the diagnosis of subclinical hepatic encephalopathy and prediction of overt encephalopathy. Liver 2002;22:190-197.

23 Papatheodoridis GV, Goulis J, Leandro G, Patch D, Burroughs AK. Transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt compared with endoscopic treatment for prevention of variceal rebleeding: A meta-analysis. Hepatology 1999;30:612-622.

24 Nolte W, Wiltfang J, Schindler C, Münke H, Unterberg K, Zumhasch U, et al. Portosystemic hepatic encephalopathy after transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt in patients with cirrhosis: clinical, laboratory, psychometric, and electroencephalographic investigations. Hepatology 1998;28:1215-1225.

25 Hartmann IJ, Groeneweg M, Quero JC, Beijeman SJ, de Man RA, Hop WC, et al. The prognostic significance of subclinical hepatic encephalopathy. Am J Gastroenterol 2000;95:2029-2034.

26 Ortiz M, Jacas C, Córdoba J. Minimal hepatic encephalopathy: diagnosis, clinical significance and recommendations. J Hepatol 2005;42:S45-53.

27 Gorbach SL. Probiotics and gastrointestinal health. Am J Gastroenterol 2000;95:S2-4.

28 Liu Q, Duan ZP, Ha DK, Bengmark S, Kurtovic J, Riordan SM. Synbiotic modulation of gut flora: effect on minimal hepatic encephalopathy in patients with cirrhosis. Hepatology 2004;39:1441-1449.

29 Malaguarnera M, Greco F, Barone G, Gargante MP, Malaguarnera M, Toscano MA. Bifidobacterium longum with fructo-oligosaccharide (FOS) treatment in minimal hepatic encephalopathy: a randomized, double-blind, placebocontrolled study. Dig Dis Sci 2007;52:3259-3265.

30 Lata J, Jurankova J, Kopacova M, Vitek P. Probiotics in hepatology. World J Gastroenterol 2011;17:2890-2896.

31 Sharma P, Sharma BC, Puri V, Sarin SK. An open-label randomized controlled trial of lactulose and probiotics in the treatment of minimal hepatic encephalopathy. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol 2008;20:506-511.

Received February 24, 2014

Accepted after revision June 17, 2014

Author Affiliations: Department of Surgery, Zhejiang University Hospital, Zhejiang University, Hangzhou 310027, China (Xu J, Ma R, Chen LF, Zhao LJ, Chen K and Zhang RB)

Ren-Bing Zhang, MD, Department of Surgery, Zhejiang University Hospital, Zhejiang University, Hangzhou 310027, China (Tel: +86-571-87952581; Email: zrb94276@zju.edu.cn)

© 2014, Hepatobiliary Pancreat Dis Int. All rights reserved.

10.1016/S1499-3872(14)60280-0

Published online July 17, 2014.

Hepatobiliary & Pancreatic Diseases International2014年4期

Hepatobiliary & Pancreatic Diseases International2014年4期

- Hepatobiliary & Pancreatic Diseases International的其它文章

- Effect of external beam radiotherapy on patency of uncovered metallic stents in patients with inoperable bile duct cancer

- Ultrasonic integrated backscatter in assessing liver steatosis before and after liver transplantation

- Liver transplantation using organs from deceased organ donors: a single organ transplant center experience

- Prostacyclin decreases splanchnic vascular contractility in cirrhotic rats

- A matched-pair analysis of laparoscopic versus open pancreaticoduodenectomy: oncological outcomes using Leeds Pathology Protocol

- Effects of melatonin on the oxidative damage and pancreatic antioxidant defenses in ceruleininduced acute pancreatitis in rats