规范化的好奇心:艺术教学,设计和艺术教育研究

Dr. Michelle Tillander(米歇尔•蒂兰德)Assistant Professor of Art University of Florida,32670 Florida ,USA(佛罗里达大学32607,佛罗里达,美国)

规范化的好奇心:艺术教学,设计和艺术教育研究

Dr. Michelle Tillander(米歇尔•蒂兰德)

Assistant Professor of Art University of Florida,32670 Florida ,USA(佛罗里达大学32607,佛罗里达,美国)

21世纪的研究方法不断进步,这是因为技术的进步为艺术的表现、管理和信息共享提供了创建性的方法。这种衍变再次反映出在艺术研究中,对身处变化的当今世界中的艺术教育者的立场和角色进行研究的重要性。现今广泛运用的技术诸如移动应用程序、数据分析以及社会媒介正在重新塑造内容与思想以及实际应用研究之间的关系。论文阐述了研究方法在理解艺术研究实例和提供视角方面所起到的关键作用。一个有效的教育模式可以使艺术专业的学生将他们特有的知识和文化运用到研究和艺术实践之中。

视觉艺术;设计;艺术教育;研究方法

What is art, design, and art education research in the 21st century? Art, design, and art education research are questions and methodologies, which explore the nature of art, its contributions to human development and society, and arts role in one's culture. The National Endowments for the Arts (2012) report promotes knowledge and understanding about the contributions of the art. The five year agenda describes research that emanates from outside the arts.

Some of the most compelling research has originated in non-arts specialties: cognitive neuroscience, for example, with its discoveries about the arts’ role in shaping learningrelated outcomes; labor economics, with its lessons about the arts’ bearing on national and local productivity; urban planning fieldwork that seeks to understand the arts as a marker of community vitality; and psychological studies that posit the arts’ relationship to health and well-being. (p. 6)

In this context arts impact is valued in the personal,social, and cultural context. Creating art or experiencing art is at the core of how art works and demonstrates how our society invents and expresses itself. The increasing scope of change and shifting contexts of technology are sound reasons for re-examining the ideas and methods we use to support researchers~practitioners~activists. Contemporary art research is emerging amidst a nexus of converging social, mobile, technology, and information forces. The Horizon Report Higher Education Edition (2013) sites the emergence of new scholarly forms of authoring, publishing, and researching; all of which are outpacing modes of assessment, especially research involving social media. The report also notes that academics are not using technology to organize their own research, citing many reasons for these fi ndings and acknowledge the challenges this present. These challenges are indicative of the changing nature of how we communicate, access information, connect with colleagues, learn, and socialize and ultimately conduct research.

Research in the arts and design becomes an interplay among artists, artworks, and audiences. “Research is formalized curiosity. It is poking and prying with a purpose. It is a seeking that he who wishes may know the cosmic secrets of the world and they that dwell therein.”(Neale-Hurston, 1942, p. 143) At the center of poking and prying with a purpose, the graduate students in the School of Art and Art History (SAAH) in the College of Art at the University of Florida (UF) are being embedded in the complex relationships between research, creative practices, and production. Sullivan (2005) argues “The notion that research is a cultural practice does not mean that there is any loss of specificity in establishing the relationship between theory and practice, nor the methodological demands of conducting research that is focused, rigorous, and trustworthy.” (p.85) He sees the similarities between theory and practice, not the differences, as offering possibilities. The university is a site where knowledge constructed through dialogue, practice, and theory are interdependent. In a dialogical education, learners and educators are regarded as “equally knowing subjects” by engaging in critical thinking (Freire, 1972, p. 31). This positions student as teachers, and as such, the student and teacher become jointly responsible for the process in which everyone grows (p.53).

Several key aspects of the research methods class I teach in the School of Art and Art History include: engaging students in developing their research proposals, conducting literature reviews in an area of research interest, becoming critical consumers of research, and identifying procedures involved in planning a scholarly research project. Graduate students also consider the equally important elements of logic and paradigms behind the research design as a way to recognize philosophical and epistemological implications for choosing research methods and procedures. Denzin and Lincoln (2005) discuss interpretive paradigms as “the net that contains the researcher’s epistemological, ontological, and methodological premises.” (p. 22) As students begin to explore their own research, they consider the possible lens that frame their approaches:

Understanding interpretive and philosophicalorientations is a strategy to assist new researchers in conceptualizing research designs and interrogate their own values, assumptions, and beliefs. This premise provides a foundation in choosing a method to answer a research question and a justif i cation as why an approach is selected. Consequently, students open themselves to new ways of understanding as a useful action for change.

The act of producing, experiencing, and interpreting, empowers artists, designers, and art educators to communicate with others in unique forms, processes, and systems. The diversity of creative disciplines in the arts offers the potential to explore questions of signif i cance to our world. Candy (2006) describes practice-led research as research that intends to advance knowledge within a practice. Nimkulrat & O’Riley (2012) argue that,

The practitioner-researcher’s creative practice thus demonstrates a way or form of knowing that can be integrated with the traditional realm of knowledge in academic research. Research through or for art and design has been labeled with various terms: practice-based, practice-led, art-led, artistic research, etc. With no clear boundaries drawn between them, these terms have been used rather interchangeably to describe the individual research projects undertaken by artists or designers. (p. 8)

As Gray and Malins (2004) point out, research in art and design involves a variety of methods–primarily visual–originating from practice, or adapted for practiceled research from a selection of research paradigms. They advocate “playing with ideas,” embracing an “imaginative agenda”, and “to extend our capacity for creative responses” to reframe our position and understanding by playing with data to visualize our thoughts and ideas and make the invisible visible (p. 33) as an occasion to visualize research differently.

Laurel (2003) considers the action of designing-asresearch as a way to provide new imaginings of design research; one which helps designers investigate people, forms, and processes. The studio art MFA and art education graduate students investigate their practices, educators/ artists, and theories placing equal weight on both practice and theory. Designers, artists, and art educators research through practice and use creative techniques in tandem with traditional methods to generate knowledge about issues. They research art practice by generating knowledge about approaches, techniques, and thinking in art. They can use research to understand research practices in the arts, which can include observing art, reading about art, or more conventional methodologies of research such as, ethnography, surveys, case studies, and interviews. As Polanyi (1969) asserts, knowing and doing is a combination of all our senses and knowing moves us from internal clues to external evidence.

Reflecting on and documenting research is an important strategy in the research class to develop our own theory of the nature of things. As researchers, we analyze and reflect on practice with the help of documentation. Although documentation does not have to be digital, the accessibility, and variety of interfaces of digital documentation expands the position of what Schön (1983) calls “ref l ection-in action” for the artist researcher.

Through the unintended effects of action, the situation talks back. The practioner, ref l ecting on this back-talk, may fi nd new meaning in the situation which lead him to a new reframing. Thus he[sic] judges a problem-setting be the quality and direction of the ref l ective conversation to which it leads. This judgment rests, at least in part, in his[sic] perception of potentials for coherence and congruence which he[sic] can realize through his[sic] further inquiry. (p. 135)

Schön (1983) proposes that the researcher, as a reflective practitioner, should understand the nature and origin of knowledge that is woven into the actions of practice. Research documents can now be dynamic, easily reproducible, interactive, recombinant, and virtual. As the research pieces and methods become easy to use, researchers will be able to bring ideas and data togetherin new ways and ask new questions. For example, I use an online tool called Wordle (http://www.wordle.net/) as a strategy with the graduate students to ‘see’ their abstracts. The online tool generates visual representation of the content as a “word cloud” that gives greater prominence to words that appear more frequently in the source text. (See Fig. 1)

Figure 1. Wordle of this article abstract.

Generating the Wordle from student’s writing helps coalesce central ideas, screen out over-used words, and reflects visually on the content of students’ research statements or abstracts.

What Makes a Good Research Problem?

In addition to these philosophical considerations, it is also import for new researchers to be both creative, pragmatic, and passionate. Identifying a research problem is very important and should be a topic or issue that ignites students’ passions, be researchable, and fulfill the goal of the research. Passion is a form of internalization of an activity into one’s identity and is a fundamental part of the life-long process of the co-construction of knowledge, the creation of the new knowledge, and the development of self. Clearly articulated research questions and objectives enable the questions to be explored and answered. In addition, the context and rational for the questions help to clarify what other research has been done and what contribution the research will make. Design encompasses both a systematic approach with rules and evidence, and contextualized practices that are constantly negotiated relative to circumstances and expressions that are personal, community focused and social. “Design stands midway between content and expression. It is the conceptual side of expression, and the expression outside of conception.”(Kress et al. 2001, p. 5) Here a series of culturally charged, and thus conventionalized signs, are employed for meaning making purposes. More importantly, design (and its process) can be improved upon through iterations of re fl ection, action, and research. Design thinking is creative thinking-in-action that is a combination of mind, action, and world. http://www.designthinkingforeducators.com/ design-thinking

Research problems can take the form of a declaration or a question. I recommend a question so that students can challenge their understanding and solidify their knowledge by making connections, determining importance, synthesizing ideas. Milisa Taylor-Hicks (2006) art education project entitled Photography Through a Visual Culture Lens uses the following questions for her research:

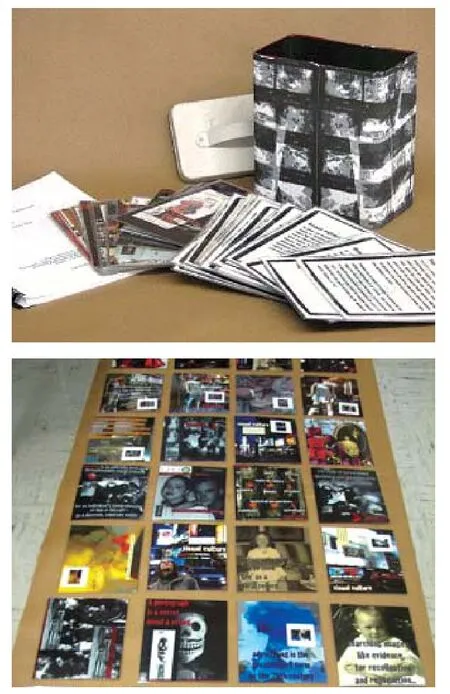

Taylor-Hicks produced a visual-culture-inphotography curriculum resource guide for art educators. The curriculum took the form of an interactive set of cards. (See Fig. 2) Taylor-Hicks used a three-part research method. First, she observed forms of visualization and representation in the photography of fi rst year undergraduate photography students. Second, she looked at the current dialogue around visual culture within art education practices. Finally, she determined how each of these areas factored into her own teaching practices and created the set of cards.

Figure 2. Milisa Taylor-Hicks capstone project.

The research question in a practical way must be answerable, so it must be researchable; meaning students must be able to provide evidence by posing and answering the question. Addressing the problem or answering the question must also meet the goal of the research. This process often takes several iterations by the student, and often benefits from peer feedback. Clarity and specificity of the actual words that are used for the question and problem statements are important so that the fi ndings and interpretations can focus on a target. Here again Wordle can serve as an analytic tool to see the actual focus of the text.

I engage students in research to acquaint them with the literature related to the main content of their research topic. This can be written text or artifacts as in the case for studio or design disciplines. These processes help focus the research topic, question, and signif i cance and respond to my favorite prompt and to play–the SO WHAT game. I challenge students to consider critically their assumptions and biases, and reveal these biases to the research audience as part of their role of researcher. Exploring and fieldtesting research methods on a small scale enables students to take on the project that is doable and appropriate for their research question.

The capstone defenses in the UF School of Art and Art History include an oral presentation, a project, and a supporting paper. In the supporting paper, art students write about their research. This can also take a very creative form with the possibilities of hypelinking and embedding multimedia. For example, a MFA Research project by Sheila Bishop(2010)–a performance artist–was a performance art piece entitled, In Defense of Fools; her supporting paper was an interactive document, Bishop Bishop’s Mission to save the whole wide world and little old you, that included screen capture images, hyperlinks and embedded videos documenting her creative performance practice. (See Fig. 3)

Figure 3. Page 53 and 54.

Our graduate art education students are using very innovative social media sites to document and share their research data and final research projects. (See Fig. 4) Sweeney (2013) included social media venues of where she will disseminate her art education capstone project entitled, Objects and Meaning: A Material Culture Curriculum for a High School Photography Class. The purpose of Sweeney’s capstone project was to create a material culture curriculum that investigated the enduring ideas of identity, memory, and consumerism that guided her research of contemporary artists working with material culture.

Figure 4. M. Sweeney slide demonstrating where she will publish her research.

Digital interfaces offer students a variety of ways to conduct research as well as publish research. Digital technologies have vast potential in offering conceptual spaces for new ideas and possibilities for research. They are emerging amidst a nexus of converging forces–social, mobile, and the cloud. For example, the Google Public Data Explorer (2010) (http://www.google.com/publicdata/ directory) makes large datasets easy to explore, visualize, and communicate. Users can use the interface to create visualizations of public data, link to them, or embed the data in their own webpages. Embedded charts and links update automatically so you are sharing the latest available data on any devise. This creates a seamless integration between research and publication of results. Tools such as SurveyMonkey (http://www.surveymonkey.com/), an online survey tool, allow graduate students to include expanded resources to their local context. Social media tools such as personal web sites, Pinterest communities of practice, such as Art Education 2.0 (http://arted20.ning. com/), add texture to students' professional resources and sites of practice.

Our art students as researchers take risks and use creative and critical methods to create the research interface for their capstone projects. Art educator Moran (2013) documents her ceramic students work using Pinterest (http:// pinterest.com/morankd/contemporary-issues-capturedin-clay-as-seen-throu/ ) for her art education research entitled, Incorporating Contemporary Pottery Approaches into a High School Ceramics Course. Similarly, Shutt’s (2011) art education research Prompted Performance was the creation of a web-based framework (http://kwshutt. wix.com/home#!prompting-performance) that facilitates the incorporation of performance art into the high school art curriculum to appeal to students who live in a world of advanced and omnipresent technology. (See Fig. 5) Both of their processes involved multiple iterations of reflection~in~action for the online interface as well as the supporting papers. The mixing of actual and virtual through technology offers inf i nite creative research options.

Figure 5. Prompted Performance research project.

Art educator Farrell’s TeachArt site (http://teachart. org/) provides the documentation of her capstone research project entitled, Junctions of Contemporary Art Trends and New Methods of Art Education (2012), as an interface in the form of a concept map, conceptual framework, and resources. Additionally the site offers a connection toFarrell through social media twitter, Facebook, Linked, and Pinterest. The research process, product, and the dissemination of fi ndings are enacted through the interface of her web site. Her active participation through revisions and interpretations continuously engages both the process and distribution embedded in her creative research.

Implication and Summary

A principle aim of this article is to provide insights into teaching a methods course for a creative practice discipline such as the visual arts. These insights include a critical examination of the ideas about art knowledge that is intellectually [un]certain at a particular time. Developing research questions and designs, methods, data collections, samplings, ethics, validity, reliability, and rigor are all typical topics and processes of a research class. There are additional issues in the research course, which are essential to the research process and emanate from the content and process of individual research. For example, theoretical perspectives and epistemologies are key for creatively designing and critically understanding research. Understanding the logic and paradigms of these viewpoints assists students in identifying any biases or assumptions in their research and arguments to recognize that research is not value-neutral and to make sense of subjective worldviews. The process engages critical and creative thinking and ref l ection and the often uncomfortable role of subjectivity in research and the production of knowledge.

People and their interactions are more than a collection of objective, measurable facts; they are seen and interpreted through the researcher's frame- that is, how she or he organizes the details of an interaction, attributes meaning to them, and decides (consciously or unconsciously) what is important and what is of secondary importance or irrelevant. (Brown, 1996, p. 16)

Documentation during the research process provides an examination space for cognitive evidence. Reflection on artifacts and processes provides researchers the ability to appreciate the continuum between practice, theory, and research. In addition, it is important to discuss research as a professional practice outside of academia in the ‘real world’. The researcher-as-activist and the researcher-aspractitioner are roles, which move research beyond the university. If you want to understand art, you should not look only at the theories or fi ndings and certainly not at the critiques; you should look at what the practitioners of art do. Art research enables us to uniquely understand research, and to recognize the distinctive characteristics of “art” as a discipline and as an integral part of life. By empowering our graduate students to reflect on their practices of research as a process of visual art knowledge and learning, they further ref l ect on how art functions in the 21st century.

Bishop, S. (2010). Bishop Bishop’s mission to save the whole wide world and little old you. Unpublished MFA project, The University of Florida, Gainesville, Florida.

Brown, J. R. (1996). The I in science: Training to utilize subjectivity in research. Oslo, Norway: Scandinavian University Press.

Candy, L. (2006). Practice-based research: A guide. Retrieved from http://www.mangold-international.com/ fileadmin/Media/References/Publications/Downloads/ Practice_Based_Research_A_Guide.pdf

Denzin, N. K. & Lincoln, Y. S. (2005). Introduction: The discipline and practice of qualitative research. In N. K. Denzin & Y. S. Lincoln (Eds.), The sage handbook of qualitative research (2nd ed.). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Denzin, N. K. (1994). The art and politics of interpretation. In N. K. Denzin and Y. S. Lincoln (Eds.). Handbook of qualitative research (pp. 500-516). Thousand, Oaks, CA: Sage.

Farrell, K. (2012). Junctions of contemporary art trends and new methods of art education. Unpublished MA capstone project, The University of Florida, Gainesville, Florida.

Freire, P. (1989). Pedagogy of the oppressed. New York: Continuum.

Gray, C. & Malins, J. (2004). Visualizing research: A guide to the research process in art and design. Burlington, VT: Ashgate Pub Ltd.

Kress, G. and Van Leeuwen, T. 2001. Multimodal Discourse: The Modes and Media of Contemporary Communication. New York, NY: Oxford University Press. Print.

Laurel, B. (2003). Design research: Methods and perspectives. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Moran, K. (2013). Incorporating contemporary pottery approaches into a high school ceramics course. Unpublished MA capstone project, The University of Florida, Gainesville, Florida.

National Endowment for the Arts. (2012). How art works: The National Endowment for the Arts' five-year research agenda, with a system map and measurement model. S. Iyengar, E. Grantham, R. Heeman, R. Ivanchenko, B. Nichols, T. Shingler, S. Shewfelt, J. Woronkowicz. Retrieved from http://www.nea.gov/ research/How-Art-Works/

Neale-Hurston, Z. (1942). Dust tracks on a road. NY: Harper Perennial Modern Classics.

Nimkulrat, N. and O’Riley, T. (Eds.). (2012). Ref l ections and connection’s: On the relationship between creative production and academic research. Retrieved from https://www.google.com/url?sa=t&rct=j&q=&esrc=s&sour ce=web&cd=1&cad=rja&ved=0CC8QFjAA&url=https%3 A%2F%2Fwww.taik.f i %2Fkirjakauppa%2Fimages%2Ff5d 9977ee66504c66b7dedb259a45be1.pdf&ei=bUjwUePMD4 Tc9QTg7IGQAQ&usg=AFQjCNFHnUbsg7r7EIaHXXyl2 BCmurmiAw&sig2=COuUbWd7Q5cK8DhnbrrYUQ&bvm =bv.49641647,d.eWU

Polanyi, M. (1969). Knowing and being. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Schön, D. (1983). The reflective practitioner: How professionals think in action. NY: Basic Books.

Shutt, K. (2011). Prompted performance. Unpublished MA capstone project, The University of Florida, Gainesville, Florida.

Sullivan, G. (2005). Art practice as research: Inquiry in the visual arts. Thousand Oaks, CA; Sage.

Sweeney, M. (2013). Objects and meaning: A material culture curriculum for a high school photography class. Unpublished MA capstone project, The University of Florida, Gainesville, Florida.

Taylor-Hicks, M. (2006). Photography through a visual culture lens. Unpublished MA capstone project, The University of Florida, Gainesville, Florida.

The New Media Consortium. (2013). The NMC horizon report: 2013 higher education edition. Austin, TX: Johnson, L., Adams Becker, S., Cummins, M., Estrada, V., Freeman, A., and Ludgate, H.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Dr. Michelle Tillander: Dr. Tillander joined the University of Florida (UF) Art Education Department in 2006 as assistant professor of Art Education. Michelle and her colleague Craig Roland initiated an online MA in Art Education at the University of Florida in 2010. Her research activities include engaging art education, technology, and culture as integrated processes and approaches to expand art educational technology practice. Tillander published a chapter entitled Digital Visual Culture: The Paradox of the [In]visible in Intersection/Interaction: Digital Visual Culture (2011). She presents at state and national conferences, most recently the 2012 International Conference City Aesthetics in Taiwan. She currently serves on the NAEA's Materials and Publications Editorial Board. Prior to UF, Tillander attended Pennsylvania State University where she completed her doctorate in Art Education, which included coordinating the Zoller Gallery.

关于作者——米歇尔·蒂兰德

获得宾夕法尼亚州立大学艺术教育学博士学位。2006年起在佛罗里达大学艺术教育系任教,为艺术教育学助理教授,并兼职于国家艺术教育协会资料和出版编辑部。2010年,与同事一起创办了佛罗里达大学“在线艺术教育学”硕士研修班。硕士研修班的研究主题包括将艺术教育与技术和文化集成用于扩大艺术教育技术上的实践。参加州及国家的相关学术会议,曾出席过中国台湾省举办的2012年度城市美学国际会议。

Formalized Curiosity : Teaching Art , Design and Art Education Research

Research in the 21st century is evolving as technology offers creative methods for the arts to conduct, manage, and share research. This evolution recasts the importance of arts research in understanding Art Educators' location and role in a rapidly changing world. Pervasive and ubiquitous technologies like mobile applications, data analytics, and social media are reshaping the relationships between content, thinking, and practice of research. This article identif i es key aspects of teaching research methods providing insights on strategies and illustrating examples of research in the arts. An effective pedagogical model enables art graduate students to apply their unique knowledge and culture into their research process and art practice.

Visual Arts;Design; Art Education;Research Methods

J04

A

10.3963/j.issn.2095-0705.2013.05.024(0113-08)

2013-08-16

米歇尔·蒂兰德,博士,美国佛罗里达大学艺术教育系助理教授。