人类免疫缺陷病毒1型gp41结构与功能的研究进展

姚茜茜,吕钧,叶荣

复旦大学上海医学院,上海 200032

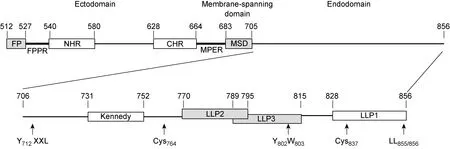

自1981年首次发现获得性免疫缺陷综合征(acquired immune deficiency syndrome, AIDS)迄今已有30年,该病已成为世界上危害最为严重的传染病之一。截至2009年,已造成3 330多万人感染,1 800多万人死亡[1]。AIDS的病原体——人类免疫缺陷病毒1型(human immunodeficiency virus type 1, HIV-1)是一种RNA反转录病毒,通过其包膜糖蛋白(envelope glycoprotein, Env)介导,侵入宿主细胞[2]。HIV-1表面的Env为gp120和gp41两个亚单位非共价结合组成的异二聚体,两者由其前体gp160经宿主细胞的蛋白酶裂解产生[3]。HIV-1通过gp120识别细胞膜表面主要受体CD4和辅助受体CC趋化因子受体5﹝C-C chemokine receptor type 5,CCR5)或CXC趋化因子受体4(C-X-C chemokine receptor type 4,CXCR4﹞,并激活gp41发生变构,引起病毒-细胞膜融合,从而进入细胞[4]。HIV-1 gp41通常由345个氨基酸残基组成,分为3个主要结构功能区域:膜外区(ectodomain)、跨膜区(membrane-spanning domain, MSD) 和膜内区(endodomain)。每个区域内含有多个结构域(domain)或基序(motif),参与不同的生物学功能。膜外区主要与膜融合功能有关;MSD通过疏水作用锚定在质膜上;而膜内区也称为胞质尾区 (cytoplasmic tail, CT),其功能往往呈现多样化[5](图1、表1)。因此,gp41除与gp120共同参与病毒构成外,在HIV-1的复制与致病过程中也有独特的重要作用。本文对其结构与功能,尤其是膜内区的研究进展进行简要综述。

1 膜外区的结构与功能

gp41膜外区含有一些特殊的功能决定簇,直接参与病毒与宿主细胞融合,同时也是比较活跃的抗原表位区域。gp41膜外区氨基端的16个氨基酸(512~527残基)为富含Gly的疏水性融合肽(fusion peptide, FP),其在融合过程中的作用已被较好阐明,具有结构多态性[6]。FP在二甲亚砜(dimethyl sulfoxide,DMSO )中为无序结构,在含水缓冲液中形成聚集的α螺旋、β折叠及无序结构的混合体[6]。将十二烷基磷酸胆碱(dodecylphosphocholine, DPC)微粒包埋的FP进行溶液核磁共振(nuclear magnetic resonance,NMR)显示,在感染过程中FP最有可能的构象是α螺旋[7]。当脂质双层中胆固醇浓度低时,α螺旋是FP的主要构象,反之则部分转换成β折叠[8]。非融合态的FP包藏在gp120/gp41复合体中,只有gp120与CD4结合后才会短暂暴露[9]。Gly是FP融合过程中构象变化所必需的,促使FP带动病毒蛋白倾斜插入,从而使膜失去稳定性,最终导致膜融合发生[10]。此外,FP下游的13个氨基酸(528~540残基)称为融合肽近侧区(fusion peptide proximal region, FPPR),其可溶性部分与gp41的近膜外部区(membrane proximal external region, MPER)的可溶性部分在HIV-1感染过程中相互作用,能释放更多的自由能,从而增强Env三聚体的稳定性[11]。

HIV-1 gp41具有典型的I型病毒膜融合蛋白特征,其膜外区有2个七肽重复序列(heptad repeat, HR),位于氨基端称NHR或HR1(541~580残基),位于羧基端称CHR或HR2(628~664残基)(图1)。在膜融合过程中,NHR和CHR形成六螺旋束(six helix bundle, 6-HB),3股NHR螺旋位于中心,3段CHR螺旋以反向平行的方式包绕自身NHR螺旋,形成桶状结构[12,13]。6-HB的形成使FP和MSD向同一脂质双层相互靠近,克服能量阻碍,激活Env复合体形成融合孔,导致细胞脂质双层的稳定性破坏,从而与病毒包膜发生融合[13-15]。6-HB间的疏水作用是影响其稳定性的主要因素,CHR结合在NHR形成的沟槽中[12]。沟槽含有由非常保守的疏水残基构成的深穴核心结构,疏水残基突变会破坏6-HB核心结构的形成[16]。

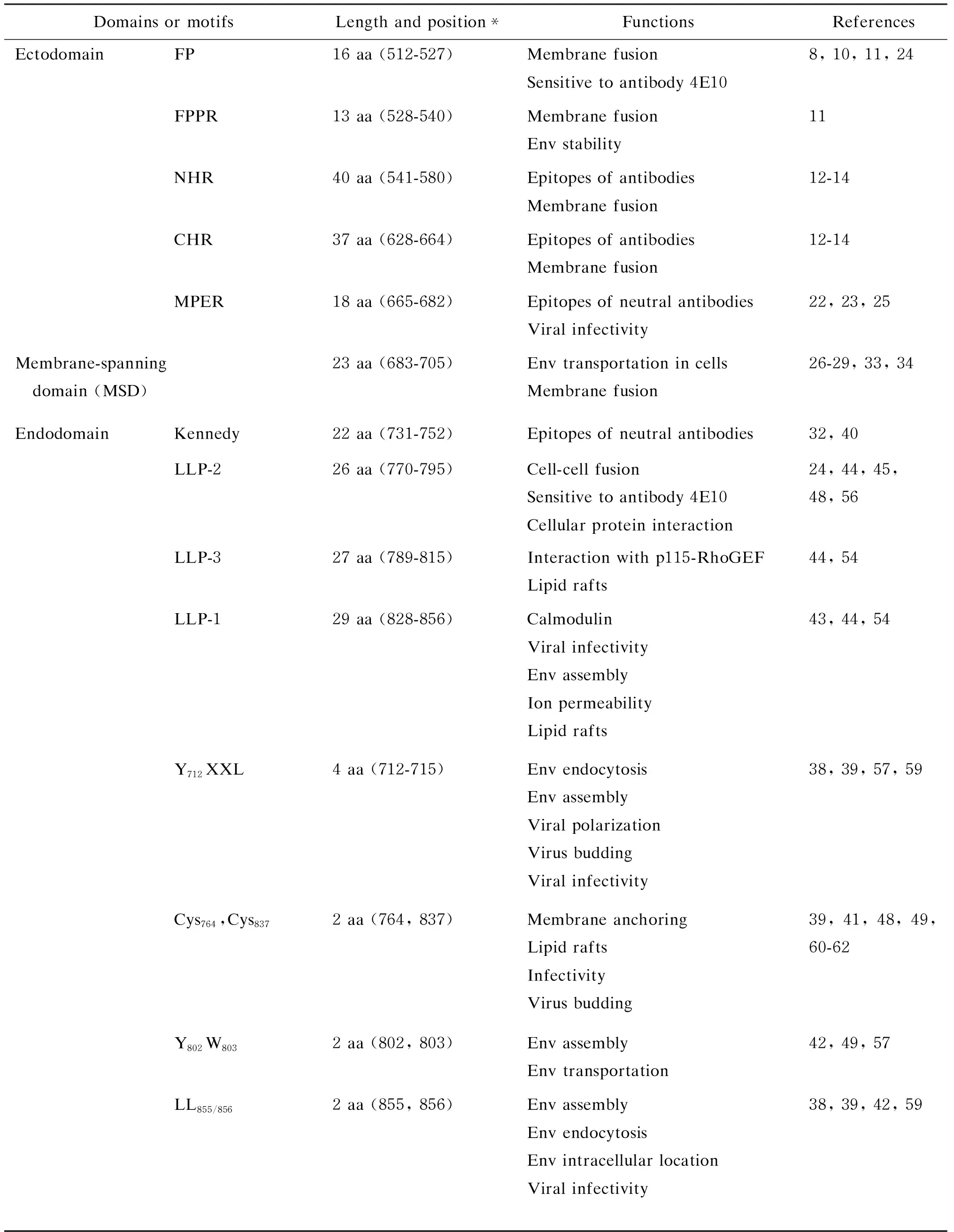

*The residue numbering is based on HIV-1 HXB2 gp160.

图1HIV-1gp41的结构域

Fig.1DomainsandmotifsofHIV-1gp41

表1HIV-1gp41的主要结构域及其功能

Tab.1FunctionsofthedomainsormotifsinHIV-1gp41

Domains or motifsLength and position*FunctionsReferencesEctodomainFP16 aa (512-527)Membrane fusionSensitive to antibody 4E108, 10, 11, 24FPPR13 aa (528-540)Membrane fusionEnv stability11NHR40 aa (541-580)Epitopes of antibodiesMembrane fusion12-14CHR37 aa (628-664)Epitopes of antibodiesMembrane fusion12-14MPER18 aa (665-682)Epitopes of neutral antibodiesViral infectivity22, 23, 25Membrane-spanning domain (MSD)23 aa (683-705)Env transportation in cellsMembrane fusion26-29, 33, 34EndodomainKennedy22 aa (731-752)Epitopes of neutral antibodies32, 40LLP-226 aa (770-795)Cell-cell fusionSensitive to antibody 4E10Cellular protein interaction24, 44, 45, 48, 56LLP-327 aa (789-815)Interaction with p115-RhoGEFLipid rafts44, 54LLP-129 aa (828-856)CalmodulinViral infectivityEnv assemblyIon permeability Lipid rafts43, 44, 54Y712XXL4 aa (712-715)Env endocytosisEnv assemblyViral polarizationVirus buddingViral infectivity38, 39, 57, 59Cys764,Cys8372 aa (764, 837)Membrane anchoringLipid raftsInfectivityVirus budding39, 41, 48, 49, 60-62Y802W8032 aa (802, 803)Env assemblyEnv transportation42, 49, 57LL855/8562 aa (855, 856)Env assemblyEnv endocytosisEnv intracellular locationViral infectivity38, 39, 42, 59

*The residue numbering is based on HIV-1 HXB2 gp160.

在Env的天然构象中,NHR的沟槽并不暴露,只是在融合过程中短暂出现[17]。HIV gp41核心结构中的“沟槽”和“深穴”是阻断HIV与靶细胞融合的理想靶位,相关的融合抑制剂T-20已被美国食品药品管理局批准上市[16]。

gp41膜外区的MPER由最后18个氨基酸(665~682残基)组成,高度保守、富含Trp残基且不发生糖基化,是HIV-1感染宿主细胞所必需的[18]。用DPC微粒包裹19肽的MPER(KWASLWNWFNITNWLWYIK),应用NMR发现其呈现α螺旋结构,芳香族和极性氨基酸分布在螺旋轴四周,Tyr、Ser等氨基酸处在同一平面上[19]。MPER的一些疏水性氨基酸残基如Trp666、Trp672、Phe673和Ile675,在HIV和猴免疫缺陷病毒(simian immunodeficiency virus, SIV)的分离株中都十分保守,Ala替换虽不影响细胞与细胞的融合,但会使病毒的感染性大大降低[20]。MPER的5个Trp残基全部突变为Ala,会抑制融合孔扩大及合胞体形成[21]。MPER的衍生多肽能有效渗透到脂质膜中,该区域可能参与病毒破坏脂质膜的过程[22]。有学者认为MPER区能起弯曲gp41分子构象的作用,在融合过程中拉近病毒膜与靶细胞膜的距离[22,23]。此外,MPER也可引起gp41聚集,促进融合孔形成过程中的低聚物形成,参与膜分配[5]。然而,MPER的作用机制目前还不十分清楚,也无合适模型解释其介导的融合过程。MPER含有3种HIV-1单克隆抗体(2F5、Z13e1和4E10)识别的表位,是最具吸引力的疫苗靶位区,这些中和抗体也是研究MPER相关构象转变的有力工具[5,16]。4E10抗体表位特性会随着gp41融合核心区域的结构调整而发生显著变化,如NHR上L568P突变能明显改变MPER序列中4E10相关表位的抗原性和免疫原性[24]。另外,含有6-HB的MPER重组抗原,均能与6-HB及MPER的特异性抗体作用;而且在T569A和I675V突变同时发生时,能显著提高MPER对2F5和4E10的敏感性[25]。

2 MSD的结构与功能

HIV-1 gp41的MSD由23个氨基酸(683~705残基)组成,特别是参与螺旋与螺旋间相互作用的基序GXXXG和位于疏水核心的Arg残基在不同的HIV-1分离株中高度保守,其缺失或突变会抑制Env装配膜融合及病毒的感染性[26,27]。与其他病毒如水疱性口炎病毒(vesicular stomatitis virus, VSV) 的膜蛋白不同,HIV-1 gp41的MSD还含有1个额外的Gly691(GGXXG),该基序对点突变表现较高的耐受性。G691L突变影响Env装配至病毒颗粒,但改变基序中其他2个Gly的突变株与野生型相比,只会轻微降低融合活性和延迟复制周期[27]。研究发现,3个Gly残基在gp41的MSD螺旋中成簇存在,且在其侧链存在1个氢原子,推测成簇存在的3个Gly可能使GGXXG具有更大的灵活性以适应点突变[27]。当gp41 MSD用VSV G蛋白或血型糖蛋白A或流行性感冒病毒HA蛋白的MSD替换后,病毒的融合活性受到损害[28,29]。然而,重组病毒仍具有复制能力,且这种异源替换也能增强gp160的加工能力[28]。

目前还没有得到gp41的MSD晶体结构,最初的研究结果支持gp41中存在单一MSD[30]。最近有学者提出,gp41中至少存在3个MSD,并且在多个MSD模型中,膜内区Kennedy序列以环状结构存在于膜外[31,32]。在不发生膜融合的情况下,原核和真核2种表达系统均支持单一MSD拓扑学模型;发生膜融合时,真核表达系统更倾向于多个MSD模型[31]。Arg质子化会打破MSD形成的三螺旋束的稳定性,右手螺旋结构中3个保守Arg形成链间氢键,而左手螺旋束中没有,说明三螺旋束在病毒-细胞膜融合过程中促进gp41三聚体形成[33]。计算机模型、动力学和代谢动力学方法研究发现,在亲水脂质双层膜中,MSD以倾斜的、稳定的α螺旋构象存在[34]。在水相,螺旋结构中的Gly残基形成扭曲,导致氨基端前几个残基螺旋解旋。与其他环境相比,脂质环境中gp41的MSD三螺旋束具有更高的稳定性[33]。

3 膜内区的结构与功能

HIV gp41的膜内区比其他病毒的跨膜蛋白长,有151个氨基酸(706~856残基),含有多个不同的结构域或基序,使膜内区呈现功能多样性。gp41膜内区可促进Env稳定结合于膜上并与细胞膜作用,降低脂质双层的稳定性,改变膜的离子通透性;膜内区也参与调控病毒的复制、颗粒装配和致病过程;膜内区具有诱导原核细胞及真核细胞的溶细胞效应,介导细胞杀伤等功能[35,36]。HIV-1 gp41膜内区典型结构特征是含有3段对水和脂质具有双重亲和性的ɑ螺旋,因其对细胞膜有溶解效应,故称慢病毒裂解肽(lentivirus lytic peptide, LLP)[37]。另外,一些特定的功能基序也存在于膜内区,如与蛋白内吞转运信号有关的Tyr依赖基序Y712XXL和双亮氨酸基序LL855/856[38,39],可能暴露于细胞表面,能被抗体中和的Kennedy表位[40],2个参与Env蛋白与脂筏 (lipid raft) 相互作用的、潜在的棕榈酰化位点Cys764和Cys837[41],以及1个尾连蛋白47(tail-interacting protein 47, TIP47) 作用位点Y802W803[42]。

3.1 gp41CT缺失与点突变对病毒生物学特性的影响

gp41 CT突变、缺失和截短不但降低病毒的复制、感染和致细胞病变能力,而且影响gp160的加工及Env的装配和稳定性,减缓Env的细胞表面内化、病毒颗粒脱壳及与基质蛋白(matrix protein, MA蛋白)的相互作用等[43-45]。一些CT点突变和截短突变会增加HIV-1膜融合能力及Env的表面表达和装配,或改变Env膜外区的生物化学和免疫特性[35]。截去CT能增强Env的中和敏感性,对病毒的免疫逃逸有一定作用[46];HIV或SIV的CT决定Env特异性装配至病毒颗粒,CT的改变会影响gp120/gp41复合体的稳定性[43]。体外实验证实,gp41的CT缺失会影响病毒在细胞内复制,且与病毒的细胞依赖类型有关[47]。HIV在外周血单核细胞(peripheral blood mononuclear cell,PBMC)中复制需要完整的CT,如CT缺失突变株(HIV-Env-Tr712)复制性病毒传播只发生在MT-4等一些细胞系(称允许细胞),而在大多数T细胞系如H9细胞和PBMC中不发生复制性病毒传播(称非允许细胞)[36]。另一方面,突变或截短的gp41 CT也能提高病毒膜融合效率,促进6-HB形成,增强Env对6-HB形成抑制多肽的抗性等[16]。gp41 CT的一些点突变会使病毒对一些单克隆抗体及多克隆抗体产生抗性[48]。在感染细胞中,gp41 CT通过与MA三聚体蛋白特异性的相互作用,促进Env到靶细胞 膜上装配与出芽[49]。此外,两性霉素B甲酯(amphotericin B methyl ester)通过抑制病毒进入和病毒颗粒产生而抑制HIV-1复制,但gp41 CT发生突变后产生新的蛋白酶分裂位点,导致HIV对其产生抗性[50]。

3.2 LLP

HIV gp41的LLP-1、LLP-2和LLP-3分别位于828~856残基、770~795残基和789~815残基。这3段序列在不同HIV-1分离株中高度保守,通常亲水性和疏水性氨基酸残基分别位于这些α螺旋的两面。LLP-3与LLP-1和LLP-2不同,其亲水面无带正电荷的氨基酸,而是1个亮氨酸拉链结构[51]。LLP-3中还含有1个富含芳香族氨基酸的区域,有4个Ser和2个Tyr[44]。LLP-1和LLP-2序列中一些Arg高度保守[52]。 通过光诱导的化学反应,LLP-3可插入病毒膜中[51];LLP-3也能与含有磷脂的人工膜相互作用,诱导脂质体渗漏和聚集[44]。LLP-1与膜结合后插入膜内,亲水面朝内,疏水面朝外,并与磷脂双层结合,形成1个桶状离子通道,称病毒孔道蛋白(viroporin)。该离子通道使带电离子通过,增加细胞膜的电导率,引起膜两侧离子再分布及细胞体积发生变化,最终导致细胞溶解,称“气球样退化”(balloon degeneration)。“气球样退化”与LLP的一些特殊生物功能如广谱抗菌作用及溶血作用有关[51]。此外,LLP-1与钙调蛋白、LLP-3与p115-RhoGEF蛋白羧基端的调控域发生相互作用[53]。圆二色谱(circular dichroism)和傅里叶变换红外光谱法(Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy)研究表明,LLP-1和LLP-2能使磷脂酰小囊泡释放羧基生物素,使大单室脂质体融合、破裂及引起磷脂混合,并可溶解细菌、真菌、红细胞和各种培养的真核细胞[51]。

LLP-1中一些带电荷氨基酸残基的替换或缺失会影响Env在细胞表面表达,与Env的膜融合、颗粒包装、稳定性及多聚化等功能有关[54]。有些LLP-1突变株发生复制缺陷,其感染性降低85%,与gp41装配至病毒颗粒减少有关[55]。LLP-2是Env免疫原性的关键决定簇,突变的LLP-2与野生型相比,其螺旋结构降低60%[48]。另外,LLP-2发生点突变,使gp41胞外区和gp120构象发生变化,导致Env胞外区与中和抗体的结合率降低,但不影响其CD4和辅助受体结合位点的暴露及病毒的感染性[48]。人工合成的LLP-1及LLP-2多肽,当保守Arg突变为Ala时,蛋白复合受体潜能和膜结合能力都明显下降,推测可能与Arg突变使LLP二级结构由α螺旋变为无规则卷曲结构有关[52]。

HIV或SIV中gp41 CT截短或突变可改变Env的融合性,但涉及的机制仍模糊不清,充满争议。通过细胞-细胞融合实验和在CT不同位点引入终止密码子,证实截去gp41近端至LLP-2这一区域会增加Env的融合效率,并使Env膜外区中CD4诱导的表位暴露。定量融合实验发现这些截短使融合率增加2~4倍,推测原因在于LLP-2限制了Env的膜裂解能力[35]。Kalia 等研究表明,LLP-2中的一些定点突变抑制Env的细胞-细胞融合,对病毒复制没有明显影响[55]。该突变体的膜融合活性降低90%,在T细胞中诱导合胞体形成的能力也受损,但是这种突变与细胞表面Env的表达水平大幅度下降、病毒复制及Env装配的缺陷关系不大[55]。关于这一现象的可能原因是膜融合过程中,位于膜内部的LLP-2短暂暴露至膜外并与6-HB核心结合,从而调节膜融合。此外,LLP-2可被其抗体在融合放慢时捕获,减慢了融合过程,延长了中间过渡态[56]。

3.3 与Env转运和颗粒装配相关的功能基序

膜内区一些胞吞和转导信号与HIV-1的Env蛋白在细胞膜积累、装配以及病毒感染性密切相关[38,39,57-59]。这些信号通过细胞蛋白发挥作用,如Tyr依赖基序(Y712XXL)与细胞网格蛋白衔接蛋白2 (adaptor protein 2, AP-2) 发生相互作用[39,58,60,61],而双亮氨酸基序(LL855/856)与AP-1结合[62]。

不同细胞中HIV-1颗粒包装的位置不同,如T细胞中包装主要发生于质膜,而巨噬细胞中发生于膜相关细胞器。稳定状态下,病毒感染后Env主要分布于核周围的高尔基复合体反面网络结构(trans-Golgi network, TGN)中[57]。病毒包装前Env进行定向转运,使Env在特定部位的浓度处于最适状态;Y712XXL突变会影响病毒颗粒的装配及其感染性,但两者并不一致,且与细胞类型有关[38]。Y712S突变时,病毒颗粒的装配增加2倍,同时感染性也更强;而Y712C突变时,装配水平降低3/4,感染性却增强[38]。不完整的Tyr依赖基序可使细胞表面Env表达量增加,但没有持续观察到这些突变株中Env的装配增加[59]。Y712XXL信号也依赖gp120。Y712A突变中,gp120在MT4细胞中的装配轻微降低,而在293T细胞中装配水平没有变化。Y712XXL缺失并不能完全阻断Env的内吞作用,只有同时将LL855/856删除才能完全阻碍内吞作用[59]。尽管如此,Y712XXL和LL855/856活性不具有叠加效应。一些以CCR5为辅助受体的嗜巨噬细胞病毒,其Y712A突变并不明显影响感染性或复制率[59]。LL855/856突变为Ala时,在HeLa细胞中Env显示明显的近核区域化,而在细胞质的外围则分散存在[38]。双芳香氨基酸Y802W803与TIP47结合介导Env运输,对有感染能力病毒的形成和Env装配至病毒颗粒非常重要。如在HeLa细胞中,野生型Env分布在近核区域。若Y802W803发生突变,Env则分布在细胞质的小囊泡中[42]。Y712XXL除作为内吞信号外,还与HIV的极化出芽有关[63]。

3.4 膜内区Cys残基及其与脂筏的作用

HIV-1 gp41膜内区有2个相当保守的Cys残基,分别位于LLP-2上游和LLP-1内部(Cys764和Cys837),参与Env的棕榈酰化和脂筏形成,是病毒出芽、装配所必需的[64]。如将Cys突变为Ala,会消除Env与脂筏的相互作用,并极大降低脂质膜包装,其感染性也只有野生株的40%[41]。然而,也有实验显示该棕榈酰化对病毒复制影响并不明显。如HIV分子克隆毒株pJRCSF的gp41膜内区无Cys残基,但仍有复制能力和感染性[65]。Cys764位置更靠近膜,其棕榈酰化可能有助于该Env锚定到膜上。另有学者则认为,Cys837棕榈酰化占主要作用[61]。此外,LLP-1本身也可能参与脂筏作用,并不一定与Cys有关。LLP-1截短后,Env在脂筏上的定位明显减低。点突变或替换突变也表明,LLP-1的α螺旋结构对Env与脂筏的相互作用疏水面比亲水面更重要[49]。用Pro替换疏水面的残基Val829、Val833和Ile843后,Env的脂筏作用极大削弱;替换亲水面的残基Val832、Ala839和Leu855时,对Env的脂筏作用影响相对较小[49]。

3.5 膜内区与MA蛋白的相互作用

HIV通过Env CT与Gag的相互作用调控病毒装配过程[66]。实验证明,HIV-1 MA蛋白突变会阻断Env包装,而截短或缺失的CT逆转这种包装缺陷;同样,因Env CT突变引起的装配异常也可被MA蛋白突变修正[62]。另外,MA蛋白上的一些突变也会阻碍Env转运至组装位点,如MA蛋白的一些Ser残基突变使MA蛋白的磷酸化降低,严重损害病毒与靶细胞的膜融合及其感染能力,病毒颗粒的gp120装配降低,这些损害可通过膜内区的缺失修复[64]。HIV-1和SIV的Env可指导Gag从极化上皮细胞底外侧释放,其膜内区能与MA蛋白直接作用,由LLP-2碱基缺失导致的Env装配缺陷通过MA蛋白中单个氨基酸的改变会发生逆转[45]。Gag通过自身的加工及与Env 膜内区末端的相互作用限制其融合活性,因而与未成熟病毒颗粒的感染性相关,而CT导致的Gag表达下调可能是调控病毒装配和出芽过程中的一个重要步骤[43]。

Env整合到病毒颗粒中是通过LLP与Gag基质区域相互作用发生的,然而在这一过程中究竟是LLP-1、LLP-2,还是LLP-3的作用,尚有待进一步研究[57]。Hourioux等构建了CT区的一系列多肽,发现742~835多个多肽都能与Pr55Gag颗粒结合,并推测LLP-2及其邻近区域在该过程中起主要作用[67]。Murakami的研究提供了一些MA蛋白与LLP-2相互作用的遗传学证据[45]。Piller等对LLP-1区域进行突变、缺失、替换,发现大部分突变体都对Env的装配有显著影响[68]。Kalia等研究发现,LLP-1突变株的Env装配能力显著下降,而LLP-2突变株则具备完全的Env装配能力[55]。存在于LLP-3中的双芳香氨基酸Y802W803能将Env锚定到TGN,因此LLP-3在Env的装配中也起重要作用[42,69]。

4 展望

HIV-1 gp41膜内区对病毒的复制、装配和致病过程起重要作用,但其功能发挥的确切机制仍不清楚。由于膜内区在结构和功能上不仅与gp41膜外区,还与gp120的结构和功能密切相关,因此对单个结构域的作用很难明确界定[70]。首先,较长的gp41膜内区经常发生代偿性变异,在功能上表现出灵活性。如Env与MA蛋白的相互作用调节HIV-1装配和成熟过程,两者存在明显的诱导性突变倾向,提高病毒装配能力。最近发现,这种Env膜内区变异方式使HIV-2和SIV突变体获得拮抗抑制病毒释放的Tetherin(干扰素诱导的细胞膜蛋白),从而恢复突变子的致病性[71]。其次,不同结构域或基序相互作用,共同完成Env的膜融合等功能。如果gp41膜内区尤其是Kennedy表位的拓扑结构发生变化,可能会导致MSD和膜内区其他结构域的相对位置和功能改变[31,32,56]。上述进展对了解HIV-1的感染、复制和致病机制,研发新的抗病毒药物提供了一定理论基础。

[1] Unaids report on the global AIDS epidemic 2010 [R/OL]. http://www.unaids.org/globalreport/documents/20101123_GlobalReport_full_en.pdf.

[2] Freed EO, Martin MA. HIVs and Their Replication [M]. Knipe DM, Howley PM. eds. Fields Virology. 5th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, 2007, 2108-2185.

[3] 杨金华, 叶荣. 病毒跨膜蛋白的结构功能与抗病毒药物设计 [J]. 微生物与感染, 2009, 4(4): 231-240.

[4] 周海舟. HIV-1包膜糖蛋白侵入靶细胞作用机制研究进展 [J]. 国外医学·免疫学分册, 2004, 27(4): 231-233.

[5] Montero M, Houten NE, Wang X, Scott JK. The membrane-proximal external region of the human immunodeficiency virus type 1 envelope: dominant site of antibody neutralization and target for vaccine design [J]. Microbiol Mol Biol Rev, 2008, 72(1): 54-84.

[6] Buzon V, Padros E, Cladera J. Interaction of fusion peptides from HIV gp41 with membranes: a time-resolved membrane binding, lipid mixing, and structural study [J]. Biochemistry, 2005, 44(40): 13354-13364.

[7] Li Y, Tamm LK. Structure and plasticity of the human immunodeficiency virus gp41 fusion domain in lipid micelles and bilayers [J]. Biophys J, 2007, 93(3): 876-885.

[8] Zheng Z, Yang R, Bodner ML, Weliky DP. Conformational flexibility and strand arrangements of the membrane-associated HIV fusion peptide trimer probed by solid-state NMR spectroscopy [J]. Biochemistry, 2006, 45(43): 12960-12975.

[9] Cheng SF, Chien MP, Lin CH, Chang CC, Lin CH, Liu YT, Chang DK. The fusion peptide domain is the primary membrane-inserted region and enhances membrane interaction of the ectodomain of HIV-1 gp41 [J]. Mol Membr Biol, 2010, 27(1): 32-49.

[10] Wong TC. Membrane structure of the human immunodeficiency virus gp41 fusion peptide by molecular dynamics simulation II. The glycine mutants [J]. Biochim Biophys Acta, 2003, 1609(1): 45-54.

[11] Buzon V, Natrajan G, Schibli D, Campelo F, Kozlov MM, Weissenhorn W. Crystal structure of HIV-1 gp41 including both fusion peptide and membrane proximal external regions [J]. PLoS Pathog, 2010, 6 (5): e1000880.

[12] Markosyan RM, Cohen FS, Melikyan GB. HIV-1 envelope proteins complete their folding into six-helix bundles immediately after fusion pore formation [J]. Mol Biol Cell, 2003, 14(3): 926-938.

[13] Hrin R, Montgomery DL, Wang F, Condra JH, An Z, Strohl WR, Bianchi E, Pessi A, Joyce JG, Wang YJ. Short communication: In vitro synergy between peptides or neutralizing antibodies targeting the N- and C-terminal heptad repeats of HIV type 1 gp41 [J]. AIDS Res Hum Retroviruses, 2008, 24(12): 1537-1544.

[14] Wang S, York J, Shu W, Stoller MO, Nunberg JH, Lu M. Interhelical interactions in the gp41 core:implication for activation of HIV-1 membrane fusion [J]. Biochemistry, 2002, 41(23): 7283-7292.

[15] Lorizate M, de la Arada I, Sànchez-Martínez S, de la Torre BG, Andreu D, Arrondo JLR, Nieva JL. Structural analysis and assembly of the HIV-1 gp41 amino-terminal fusion peptide and the pretransmembrane amphipathic-at-interface sequence [J]. Biochemistry, 2006, 45(48): 14337-14346.

[16] 刘叔文, 吴曙光, 姜世勃. 新型抗艾滋病药物——HIV进入抑制剂的研究进展 [J]. 中国药理学通报, 2005, 21(9): 1034-1040.

[17] Abrahamyan LG, Mkrtchyan SR, Binley J, Lu M, Melikyan GB, Cohen FS. The cytoplasmic tail slows the folding of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 Env from a late prebundle configuration into the six-helix bundle [J]. J Virol, 2005, 79(1): 106-115.

[18] Ingale S, Gach JS, Zwick MB, Dawson PE. Synthesis and analysis of the membrane proximal external region epitopes of HIV-1 [J]. J Pept Sci, 2010, 16(12): 716-722.

[19] Schibli DJ, Montelaro RC, Vogel HJ. The membrane-proximal tryptophan-rich region of the HIV glycoprotein, gp41, forms a well-defined helix in dodecylphosphocholine micelles [J]. Biochemistry, 2001, 40 (32): 9570-9578.

[20] Bellamy-McIntyre AK, Lay CS, Bar S, Maerz AL, Talbo GH, Drummer HE, Poumbourios P. Functional links between the fusion peptide-proximal polar segment and membrane-proximal region of human immunodeficiency virus gp41 in distinct phases of membrane fusion [J]. J Biol Chem, 2007, 282(32): 23104-23116.

[21] Zwick MB. The membrane-proximal external region of HIV-1 gp41: a vaccine target worth exploring [J]. AIDS, 2005, 19(16): 1725-1737.

[22] 李菁, 陆路, 吴凡, 陈曦, 牛犇, 姜世勃, 陈应华. 鉴定 HIV-1包膜蛋白gp41的近膜端外部区与其N端三聚体结构域之间的相互作用: 病毒融合相关的潜在机制 [J]. 科学通报, 2009, 54(9): 1244-1249.

[23] Apellaniz B, Nir S, Nieva JL. Distinct mechanisms of lipid bilayer perturbation induced by peptides derived from the membrane-proximal external region of HIV-1 gp41 [J]. Biochemistry, 2009, 48(23): 5320-5331.

[24] Li J, Chen X, Jiang SB, Chen YH. Deletion of fusion peptide or destabilization of fusion core of HIV gp41 enhances antigenicity and immunogenicity of 4E10 epitope [J]. Biochem Biophys Res Commun, 2008, 376(1): 60-64.

[25] Wang J, Tong P, Lu L, Zhou L, Xu L, Jiang SB, Chen YH. HIV-1 gp41 core with exposed membrane-proximal external region inducing broad HIV-1 neutralizing antibodies [J]. PLoS One, 2011, 6(3): e18233.

[26] Miyauchi K, Curran AR, Long Y, Kondo N, Iwamoto A, Engelman DM, Matsuda Z. The membrane-spanning domain of gp41 plays a critical role in intracellular trafficking of the HIV envelope protein [J]. Retrovirology, 2010, 7: 95.

[27] Miyauchi K, Curran R, Matthews E, Komano J, Hoshino T, Engelman DM, Matsuda Z. Mutations of conserved glycine residues within the membrane-spanning domain of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 gp41 can inhibit membrane fusion and incorporation of Env onto virions [J]. Jpn J Infec Dis, 2006, 59(2): 77-84.

[28] Miyauchi K, Komano J, Yokomaku Y, Sugiura W, Yamamoto N, Matsuda Z. Role of the specific amino acid sequence of the membrane-spanning domain of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 in membrane fusion [J]. J Virol, 2005, 79(8): 4720-4729.

[29] Welman M, Lemay G, Cohen EA. Role of envelope processing and gp41 membrane spanning domain in the formation of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 (HIV-1) fusion-competent envelope glycoprotein complex [J]. Virus Res, 2007, 124 (1-2): 103-112.

[30] Haffar OK, Dowbenko DJ, Berman PW. Topogenic analysis of the human immunodeficiency virus type 1 envelope glycoprotein, gpl60, in microsomal membranes [J]. J Cell Biol, 1988, 107(5): 1677-1687.

[31] Liu S, Kondo N, Long Y, Xiao D, Iwamoto A, Matsuda Z. Membrane topology analysis of HIV-1 envelope glycoprotein gp41 [J]. Retrovirology, 2010, 7: 100.

[32] Steckbeck JD, Sun C, Sturgeon TJ, Montelaro RC. Topology of the C-terminal tail of HIV-1 gp41: differential exposure of the Kennedy epitope on cell and viral membranes [J]. PLoS One, 2010, 5(12): e15261.

[33] Kim JH, Hartley TL, Curran AR, Engelman DM. Molecular dynamics studies of the transmembrane domain of gp41 from HIV-1 [J]. Biochim Biophys Acta, 2009, 1788(9):1804-1812.

[34] Gangupomu VK, Abrams CF. All-atom models of the membrane-spanning domain of HIV-1 gp41 from metadynamics [J]. Biophys J, 2010, 99(10): 3438-3444.

[35] Wyss S, Dimitrov AS, Baribaud F, Edwards TG, Blumenthal R, Hoxie JA. Regulation of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 envelope glycoprotein fusion by a membrane-interactive domain in the gp41 cytoplasmic tail [J]. J Virol, 2005, 79(19): 12231-12241.

[36] Emerson V, Haller C, Pfeiffer T, Fackler OT, Bosch V. Role of the C-terminal domain of the HIV-1 glycoprotein in cell-to-cell viral transmission between T lymphocytes [J]. Retrovirology, 2010, 7: 43.

[37] Jiang JY, Aiken C. Maturation-dependent human immunodeficiency virus type 1 particle fusion requires a carboxyl-terminal region of the gp41 cytoplasmic tail [J]. J Virol, 2007, 81(18): 9999-10008.

[38] Day JR, Münk C, Guatelli JC. The membrane-proximal tyrosine-based sorting signal of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 gp41 is required for optimal viral infectivity [J]. J Virol, 2004, 78(3): 1069-1079.

[39] Byland R, Vance PJ, Hoxie JA, Marsh M. A conserved dileucine motif mediates clathrin and AP-2-dependent endocytosis of the HIV-1 envelope protein [J]. Mol Biol Cell, 2007, 18(2): 414-425.

[40] Cleveland SM, McLain L, Cheung L, Jones TD, Hollier M, Dimmock NJ. A region of the C-terminal tail of the gp41 envelope glycoprotein of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 contains a neutralizing epitope: evidence for its exposure on the surface of the virion [J]. J Gen Virol, 2003, 84 (Pt 3): 591-602.

[41] Bhattacharya J, Peters PJ, Clapham PR. Human immunodeficiency virus type 1 envelope glycoproteins that lack cytoplasmic domain cysteines: impact on association with membrane lipid rafts and incorporation onto budding virus particles [J]. J Virol, 2004, 78(10): 5500-5506.

[42] Blot G, Janvier K, Le Panse S, Benarous R, Berlioz-Torrent C.Targeting of the human immunodeficiency virus type 1 envelope to the trans-Golgi network through binding to TIP47 is required for Env incorporation into virions and infectivity [J]. J Virol, 2003, 77(12): 6931-6945.

[43] Newman JT, Sturgeon TJ, Gupta P, Montelaro RC. Differential functional phenotypes of two primary HIV-1 strains resulting from homologous point mutations in the LLP domains of the envelope gp41 intracytoplasmic domain [J]. Virology, 2007, 367(1): 102-116.

[44] Moreno MR, Pérez-Berná AJ, Guillén J, Villalaín J. Biophysical characterization and membrane interaction of the most membranotropic region of the HIV-1 gp41 endodomain [J]. Biochim Biophys Acta, 2008, 1778 (5): 1298-1307.

[45] Murakami T, Freed EO. Genetic evidence for an interaction between human immunodeficiency virus type 1 matrix and α-helix 2 of the gp41 cytoplasmic tail [J]. J Virol, 2000, 74(8): 3548-3554.

[46] Edwards TG, Hoffman TL, Baribaud F, Wyss S, LaBranche CC, Romano J, Adkinson J, Sharron M, Hoxie JA, Doms RW. Relationships between CD4 independence, neutralization sensitivity, and exposure of a CD4-induced epitope in a human immunodeficiency virus type 1 envelope protein [J]. J Virol, 2001, 75(11): 5230-5239.

[47] Murakami T, Freed EO. The long cytoplasmic tail of gp41 is required in a cell type-dependent manner for HIV-1 envelope glycoprotein incorporation into virions [J]. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA, 2000, 97 (1): 343-348.

[48] Kalia V, Sarkar S, Gupta P, Montelaro RC. Antibody neutralization escape mediated by point mutations in the intracytoplasmic tail of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 gp41 [J]. J Virol, 2005, 79(4): 2097-2107.

[49] Yang P, Ai LS, Huang SC, Li HF, Chan WE, Chang CW, Ko CY, Chen SS.The cytoplasmic domain of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 transmembrane protein gp41 harbors lipid raft association determinants [J]. J Virol, 2010, 84(1): 59-75.

[50] Waheed AA, Ablan SD, Sowder RC, Roser JD, Schaffner CP, Chertova E, Freed EO. Effect of mutations in the human immunodeficiency virus type 1 protease on cleavage of the gp41 cytoplasmic tail [J]. J Virol, 2010, 84(6): 3121-3126.

[51] Costin JM, Rausch JM, Garry RF, Wimley WC. Viroporin potential of the lentivirus lytic peptide (LLP) domains of the HIV-1 gp41 protein [J]. Virol J, 2007, 4:123.

[52] Zhu Y, Lu L, Chao LJ, Chen YH. Important changes in biochemical properties and function of mutated LLP12 domain of HIV-1 gp41 [J]. Chem Biol Drug Des, 2007, 70(4): 311-318.

[53] Zhang H, Wang L, Kao S, Whitehead IP, Hart MJ, Liu B, Duus K, Burridge K, Der CJ, Su L. Functional interaction between the cytoplasmic leucine-zipper domain of HIV-1 gp41 and p115-RhoGEF [J]. Curr Biol, 1999, 9 (21): 1271-1274.

[54] Chen SS, Lee SF, Wang CT. Cellular membrane-binding ability of the C-terminal cytoplasmic domain of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 envelope transmembrane protein gp41 [J]. J Virol, 2001, 75(20): 9925-9938.

[55] Kalia V, Sarkar S, Gupta P, Montelaro RC. Rational site-directed mutations of the LLP-1 and LLP-2 lentivirus lytic peptide domains in the intracytoplasmic tail of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 gp41 indicate common functions in cell-cell fusion but distinct roles in virion envelope incorporation [J]. J Virol, 2003, 77(6): 3634-3646.

[56] Lu L, Zhu Y, Huang JH, Chen X, Yang HW, Jiang SB, Chen YH. Surface exposure of the HIV-1 Env cytoplasmic tail LLP2 domain during the membrane fusion process [J]. J Biol Chem, 2008, 283(24): 16723-16731.

[57] Lambelé M, Labrosse B, Roch E, Moreau A, Verrier B, Barin F, Roingeard P, Mammano F, Brand D.Impact of natural polymorphism within the gp41 cytoplasmic tail of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 on the intracellular distribution of envelope glycoproteins and viral assembly [J]. J Virol, 2007, 81(1): 125-140.

[58] Ohno H, Aguilar RC, Fournier MC, Hennecke S, Cosson P, Bonifacino JS. Interaction of endocytic signals from the HIV-1 envelope glycoprotein complex with members of the adaptor medium chain family [J]. Virology, 1997, 238 (2): 305-315.

[59] Day JR, Van Damme N, Guatelli JC. The effect of the membrane-proximal tyrosine-based sorting signal of HIV-1 gp41 on viral infectivity depends on sequences within gp120 [J]. Virology, 2006, 354(2): 316-327.

[60] Berlioz-Torrent C, Shacklett BL, Erdtmann L, Delamarre L, Bouchaert I, Sonigo P, Dokhelar MC, Benarous R. Interactions of the cytoplasmic domains of human and simian retroviral transmembrane proteins with components of the clathrin adaptor complexes modulate intracellular and cell surface expression of envelope glycoproteins [J]. J Virol, 1999, 73(2): 1350-1361.

[61] Boge M, Wyss S, Bonifacino JS, Thali M. A membrane proximal tyrosine-based signal mediates internalization of the HIV-1 envelope glycoprotein via interaction with the AP-2 clathrin adaptor [J]. J Biol Chem, 1998, 273(25): 15773-15778.

[62] Wyss S, Berlioz-Torrent C, Boge M, Blot G, Honing S, Benarous R, Thali M. The highly conserved C-terminal dileucine motif in the cytosolic domain of the human immunodeficiency virus type 1 envelope glycoprotein is critical for its association with the AP-1 clathrin adaptor [J]. J Virol, 2001, 75(6): 2982-2992.

[63] Lodge R, Lalonde JP, Lemay G, Cohen EA. The membrane-proximal intracytoplasmic tyrosine residue of HIV-1 envelope glycoprotein is critical for basolateral targeting of viral budding in MDCK cells [J]. EMBO J, 1997, 16(4), 695-705.

[64] Rousso I, Mixon MB, Chen BK, Kim PS. Palmitoylation of the HIV-1 envelope glycoprotein is critical for viral infectivity [J]. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA, 2000, 97(25): 13523-13525.

[65] Chan WE, Lin HH, Chen SS. Wild-type-like viral replication potential of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 envelope mutants lacking palmitoylation signals [J]. J Virol, 2005, 79(13): 8374-8387.

[66] Cosson P. Direct interaction between the envelope and matrix proteins of HIV-1 [J]. EMBO J, 1996, 15(21): 5783-5788.

[67] Hourioux C, Brand D, Sizaret PY, Lemiale F, Lebigot S, Barin F, Roingeard P. Identification of the glycoprotein 41TMcytoplasmic tail domains of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 that interact with Pr55Gagparticles [J]. AIDS Res Hum Retroviruses, 2000, 16(12): 1141-1147.

[68] Piller SC, Dubay JW, Derdeyn CA, Hunter E. Mutational analysis of conserved domains within the cytoplasmic tail of gp41 from human immunodeficiency virus type 1: effects on glycoprotein incorporation and infectivity [J]. J Virol, 2000, 74(24): 11717-11723.

[69] Lopez-Vergès S, Camus G, Blot G, Beauvoir R, Benarous R, Berlioz-Torrent C. Tail-interacting protein TIP47 is a connector between Gag and Env and is required for Env incorporation into HIV-1 virions [J]. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA, 2006, 103(40): 14947-14952.

[70] Bhakta SJ, Shang L, Prince JL, Claiborne DT, Hunter E. Mutagenesis of tyrosine and di-leucine motifs in the HIV-1 envelope cytoplasmic domain results in a loss of Env-mediated fusion and infectivity [J]. Retrovirology, 2011, 8: 37.

[71] Serra-Moreno R, Jia B, Breed M, Alvarez X, Evans DT. Compensatory changes in the cytoplasmic tail of gp41 confer resistance to Tetherin/BST-2 in a pathogenic Nef-deleted SIV [J]. Cell Host Microbe, 2011, 9(1): 46-57.