海洋寡毛类纤毛虫的室内培养

于 莹, 张武昌, 许恒龙, 肖 天

(1. 中国科学院 海洋研究所 海洋生态与环境科学重点实验室, 山东 青岛 266071; 2. 中国海洋大学 海洋生物多样性与进化研究所, 山东 青岛 266003; 3. 中国科学院 研究生院, 北京 100049; 4. 国家海洋局 海洋生态系统与生物地球化学重点实验室, 浙江 杭州 310012)

海洋寡毛类纤毛虫的室内培养

Laboratory culture of marine oligotrich ciliates

于 莹1,3,4, 张武昌1,4, 许恒龙2, 肖 天1

(1. 中国科学院 海洋研究所 海洋生态与环境科学重点实验室, 山东 青岛 266071; 2. 中国海洋大学 海洋生物多样性与进化研究所, 山东 青岛 266003; 3. 中国科学院 研究生院, 北京 100049; 4. 国家海洋局 海洋生态系统与生物地球化学重点实验室, 浙江 杭州 310012)

海洋寡毛类纤毛虫包括无壳寡毛类纤毛虫和砂壳纤毛虫, 是一类微小的单细胞原生动物(粒径大小在5~200 µm)。它们是微型浮游动物和海洋微食物环的重要组成部分[1], 在微食物环和经典食物链中起着重要的枢纽作用[2-3], 即完成物质和能量由pico-和nano-级生产者的初级消费者和营养再生者向 meso-级浮游动物和鱼类幼虫的传递[4]。

至今人们通过海洋野外调查已开展了大量的纤毛虫生态学研究, 但有关海洋寡毛类纤毛虫室内培养及个体及种群生态学研究一直是薄弱环节[5]。而要深入研究纤毛虫种群动力学, 纤毛虫与上下营养级之间摄食与被摄食的关系等都需要纤毛虫的成功培养作为基础。本研究总结了海洋寡毛类纤毛虫的室内培养历史、种类及条件等, 为进一步开展该类群纤毛虫的培养及下游研究提供参考。

1 海洋寡毛类纤毛虫的培养历史

海洋寡毛类纤毛虫培养的先驱是 Kenneth Gold[6], 他在 1968年首次进行海洋寡毛类纤毛虫的培养实验, 成功培养了管状拟铃虫(Tintinnopsis tubulosa)、百乐拟铃虫(Tintinnopsis beroidea)及钟形网纹虫(Favella campanula)等砂壳纤毛虫, 创立了基础培养基(Basal medium D), 为后来海洋寡毛类纤毛虫的培养工作奠定了基础。

1985年之前, 海洋寡毛类纤毛虫的培养工作进展缓慢, 培养成功的案例并不多。Heinbokel[7]在1978年成功培养了锥形旋口虫(Helicostomella subulata)、梳状真丁丁虫(Eutintinnus pectinis)、四线瓮状虫(Amphorella quadrilineata)、尖底拟铃虫(Tintinnopsiscf.acuminate)及百乐拟铃虫; Paranjape[8]在1980年成功培养锥形旋口虫; Stoecker等[9]在1981年成功培养爱氏网纹虫(Favella ehrenbergii)。

1985年, Gifford[10]建立了海洋寡毛类纤毛虫采集及培养的方法和规范, 并成功创立了目前仍为人们广泛采用的“纤毛虫培养基”。从此海洋寡毛类纤毛虫的培养进入了快速发展时期, 尤以20世纪90年代最为繁盛, 其中 Montagnes[11-12]、Stoecker[9,13-14]、Strom等[15-19]在海洋寡毛类纤毛虫的培养工作中作出了很大的贡献。

2 成功培养的海洋寡毛类纤毛虫种类

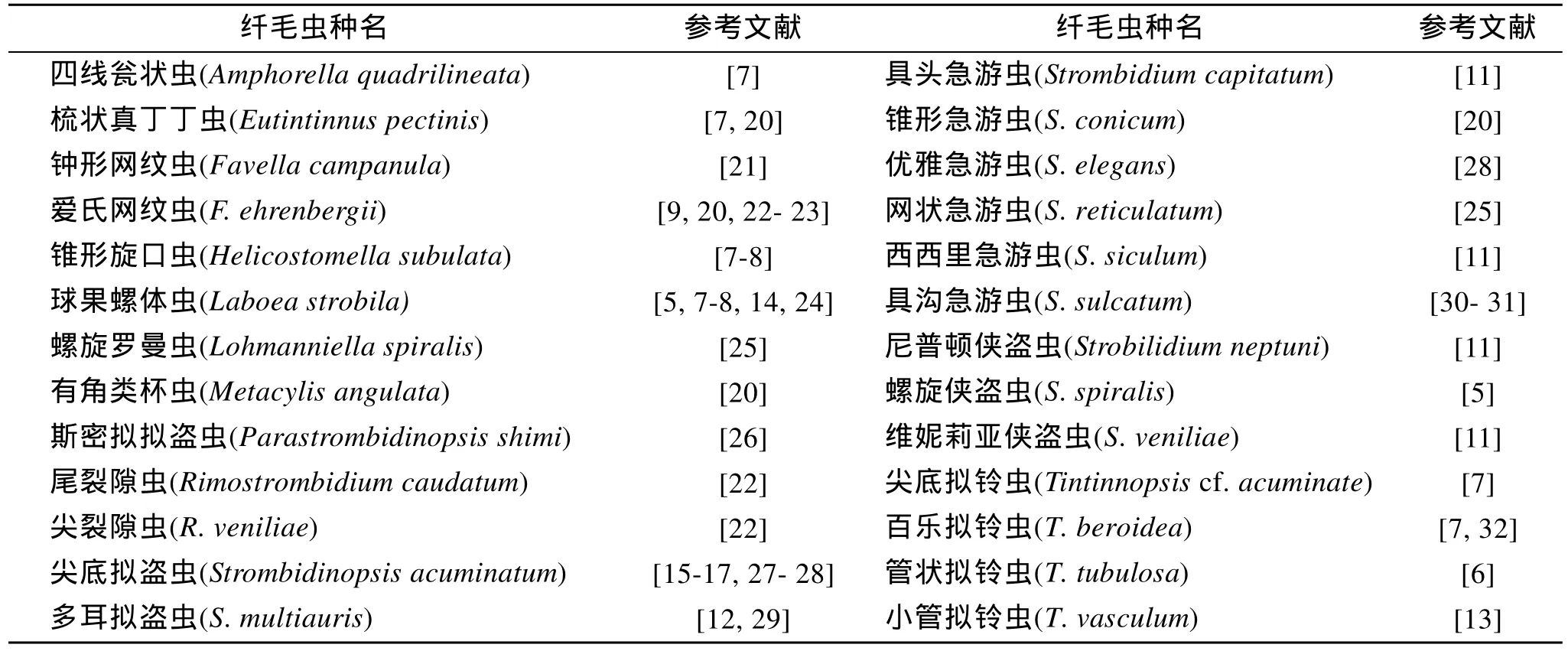

迄今人们已成功培养 13属26种海洋寡毛类纤毛虫, 其中砂壳纤毛虫 6属 10种, 无壳寡毛类纤毛虫7属16种(表1)。拟盗虫属(Strombidinopsis), 侠盗虫属(Strobilidium), 拟铃虫属(Tintinnopsis)及急游虫属(Strombidium)4属培养出的纤毛虫种类比较多, 尤其是急游虫属, 已报道的有6种。

目前, 成功培养的海洋寡毛类纤毛虫主要来自北美洲东西部近岸海区, 其中大部分分布在美国东西部海岸, 如Puget Sound、Port Aransas、Vineyard Sound及Perch Pond等。此外, 欧洲的荷兰、瑞典, 亚洲的中国、印度及韩国虽有在近岸海区成功培养海洋寡毛类纤毛虫的案例, 但普遍处于起步阶段。

表1 成功培养的海洋寡毛类纤毛虫种类

3 海洋寡毛类纤毛虫的培养条件

3.1 温度

已成功培养的海洋寡毛类纤毛虫的培养温度范围为5~30℃, 大多数集中在15~20℃, 培养温度因种而异, 尽量与采样海区的海水温度一致。

3.2 光照

培养海洋寡毛类纤毛虫与培养浮游植物相反,对光照强度要求很低, 一般弱光即可, 大都不超过40 µmol/(m2•s)。例如, 培养环纹虫属(Coxliella)需要的光照强度<10 µmol/(m2•s)[17-18,33]; 拟盗虫属需要的光照强度大都不超过 30 µmol/(m2•s)[12,15,27,29]; 侠盗虫属[13,19,34]、网纹虫属(Favella)[13,16,27]及急游虫属[13,33-34]需要的光照强度一般不超过 40 µmol/ (m2•s)。但也有些种类的培养需要的光照强度较高, 例如锥形急游虫[20]、优雅急游虫[28]、尖底拟盗虫[28]、梳状真丁丁虫[20]、有角类杯虫[20]、爱氏网纹虫[20]需要 100µmol/(m2•s); 而有些可进行光合自养的纤毛虫如球果螺体虫在约 200~300 µmol/(m2•s)的高光照强度或者15~35 µmol/(m2•s)的低光照强度下均能生长良好[24]。

与浮游植物一样, 海洋寡毛类纤毛虫的生长也需要一定的光照周期, 光照与黑暗的时间比例一般是12: 12[20]、14:10[34]或16:8[22], 也有报道培养百乐拟铃虫采用的光照与黑暗的比例为18:6[32]。

3.3 培养基

海洋寡毛类纤毛虫培养基一般采用原位海水过滤以后来配制, 采用较多的是Gifford[10]在1985年创立的 “纤毛虫培养基”。该培养基特别之处在于添加了螯合剂和微量金属元素。实验表明螯合剂(10-8~10-6mol/L)和微量金属元素能促进纤毛虫的生长。最早成功培养海洋寡毛类纤毛虫的培养基当属Gold[6]建立的基础培养基。之后也有人选用其他培养基成功培养纤毛虫的先例, 如利用NEPCC培养基成功培养了西西里急游虫[35], 利用麦粒培养基成功培养了具沟急游虫[30], 此外, 也有很多人选用浮游植物培养基, 即Guillard等[36]在1962创立及Guillard[37]在1975年改进的f/2培养基。

3.4 饵料

海洋寡毛类纤毛虫的饵料因种而异, 饵料的种类及供给量的多少等一直是纤毛虫培养中的一大难题。在已报道的文献中, 成功培养的海洋寡毛类纤毛虫的饵料大多数集中在金藻门(Chrysophyta)、甲藻门(Pyrrophyta)、绿藻门(Chlorophyta)、隐藻门(Cryptophyta)等类群, 也有报道利用一种硅藻—假微型海链藻(Thalassiosira pseudonana)成功培养西西里急游虫的例子[11]。饵料的粒级从几微米到几十微米不等,其中大多数种类具有鞭毛可以运动。纤毛虫对饵料的选择可能与细胞粒级、运动性及化学组成有关[10]。

海洋寡毛类纤毛虫饵料浓度的选择也是培养的关键。饵料的初始浓度通常控制在 103~104个/mL。Rosetta[20]在培养梳状真丁丁虫时选用的球等鞭金藻(Isochrysis galbana)浓度约为 1×103个/mL, 双凸形红胞藻(Rhodomonas lens)密度约为 1×104个/mL;Kleppel[23]在培养爱氏网纹虫时选用的球等鞭金藻、蓝隐藻属(Chroomonassp.)及裸甲藻属(Gymnodiniumsp.)的碳浓度均为 100 µg/L; Stoecker[14]在培养球果螺体虫时用的球等鞭金藻及盐沼蓝隐藻(Chroomonas salina)的密度分别为 1×104个/mL (碳质量浓度为73 µg/L)和 0.5×103个/mL (碳质量浓度为 23µg/L)。饵料的添加视情况需要而定, 可以在解剖镜下观察来确定饵料添加的频率, 一般为4~7 d添加1次[10]。培养海洋寡毛类纤毛虫时, 一般要求饵料的浓度维持较低的水平, 这可能是为了避免pH值升高而影响纤毛虫的生长[22]。

4 海洋寡毛类纤毛虫的培养时间

海洋寡毛类纤毛虫培养的时间不长。一般情况下, 分离的单克隆纤毛虫培养体系在 100个世代左右能维持较稳定的生长速率, 在200个世代以后, 接合生殖终止, 大部分的培养体系就会走向衰亡[38]。在培养钟形网纹虫的过程中, 发现有接合生殖的行为,而且在 5个月的培养时期中可以通过多次逆转衰亡的趋势而存活 2.5 a, 而其他种类的海洋寡毛类纤毛虫可能最长只能存活10个月[21]。

海洋寡毛类纤毛虫培养衰败的原因可能是有些纤毛虫由于环境条件不适合而死亡, 但大多数培养体系最终会出现自发的明显的衰败, 终止繁殖而导致死亡。这种现象在无壳寡毛类、砂壳纤毛虫及有孔虫类的培养过程中均有发现[8,39]。Gifford[10]认为出现这种衰败的原因可能是接合生殖的终止而导致培养体系随时间逐渐失去活力。

延长培养时间的方法目前尚不多。虽然无法知道一种纤毛虫体系到底能存活多长时间, 但接合生殖的终止可能是体系衰亡的一个暗示。这给我们一个启示, 在培养海洋寡毛类纤毛虫的过程中适当地改变一下培养条件可能会延长生活周期。除了增加接合生殖来延长纤毛虫的寿命以外, 还可以考虑采用其他的方法。比如, 在培养钟形网纹虫过程中, 因为培养条件比自然环境条件较适宜, 分裂速度较快而导致细胞粒级逐渐变小, 这可能导致纤毛虫的寿命较短。由此, 可以通过饥饿或者降低培养温度来减缓分裂速度从而延长生长周期[39]。

5 海洋寡毛类纤毛虫培养的下游研究

纤毛虫的成功培养可用来在实验室可控条件下研究纤毛虫的种群动力学、纤毛虫与藻类的关系及获得生态学参数等。海洋寡毛类纤毛虫获得成功培养早期, 研究多数集中在某一种或某一属纤毛虫在不同外界条件(包括温度、光照及饵料)下的生长率、摄食率的变化[7,9,11,25,30,40-41]。而后期随着水华发生的增加, Rosetta[20]、Hansen[28]、Montagnes[12]等利用纤毛虫培养研究纤毛虫对水华藻类的摄食及其在控制水华中的作用。Putt[5]利用培养成功的纤毛虫进行生物量与细胞体积之间的换算因子的实验, 得出了用鲁哥试剂固定后纤毛虫的碳含量与体积之间的转换因子为 0.19 pg/µm3。

6 小结和展望

总体来说, 寡毛类纤毛虫的室内培养很难, 需要合适的温度、光照、培养基及饵料等。中国只培养出了一种-具沟急游虫, 培养工作还需要进一步地进行。中国已经在渤海、黄海、东海、南海进行了海洋寡毛类纤毛虫的生态学调查[42], 积累了不少基础资料。但随着生态学的发展, 对生态学参数(如生长率、摄食率、生态传递效率等)的需求越来越多、越来越高, 作为进一步研究的基础, 海洋寡毛类纤毛虫的室内培养已经成为生态学研究急需突破的瓶颈之一。

[1]Azam F, Fenchel T, Field J G, et al. The ecological role of water-column microbes in the sea[J].Marine Ecology-Progress Series, 1983, 10(3): 257-263.

[2]Laval-Pento M, Heinbokel J F, Anderson O R,et al.Role of micro- and nanozooplankton in marine food webs[J].Insect Science and Its Application, 1986, 7:387-395.

[3]Pierce R W, Turner J T. Plankton studies in Buzzards Bay, Massachusetts, USA, IV. Tintinnids, 1987-1988[J].Marine Ecology-Progress Series, 1994, 112: 235-240.

[4]Pierce R W, Turner J T. Ecology of planktonic ciliates in marine food webs[J].Reviews in Aquatic Sciences,1992, 6(2): 139-181.

[5]Putt M, Stoecker D K. An experimentally determined carbon-volume ratio for marine oligotrichous ciliates from estuarine and coastal waters[J].Limnology and Oceanography, 1989, 34(6): 1097-1103.

[6]Gold K. Some observations on biology ofTintinnopsissp.[J].Journal of Protozoology, 1968, 15(1): 193-194.

[7]Heinbokel J F. Studies on the functional role of tintinnids in the Southern California Bight .1. Grazing and growth-rates in laboratory cultures[J].Marine Biology, 1978, 47(2): 177-189.

[8]Paranjape M A. Occurrence and significance of resting cysts in a hyaline tintinnid,Helicostomella subulata(Ehre) Jorgensen [J].Journal of Experimental Marine Biology and Ecology, 1980, 48(1): 23-33.

[9]Stoecker D, Guillard R R L, Kavee R M. Selective predation byFavella ehrenbergii(Tintinnia) on and among dinoflagellates[J].Biological Bulletin, 1981,160(1): 136-145.

[10]Gifford D J. Laboratory culture of marine planktonic oligotrichs (Ciliophora, Oligotrichida)[J].Marine Ecology-Progress Series, 1985, 23(3): 257-267.

[11]Montagnes D J S. Growth responses of planktonic ciliates in the generaStrobilidiumandStrombidium[J].Marine Ecology-Progress Series, 1996, 130(1-3):241-254.

[12]Montagnes D J S, Lessard E J. Population dynamics of the marine planktonic ciliateStrombidinopsis multiauris: its potential to control phytoplankton blooms[J].Aquatic Microbial Ecology, 1999, 20(2): 167-181.

[13]Stoecker D K, Verity P G, Michaels A E, et al. Feeding by larval and postlarval ctenophores on microzooplankton[J].Journal of Plankton Research, 1987, 9(4):667-683.

[14]Stoecker D K, Silver M W, Michaels A E, et al.Obligate mixotrophy inLaboea strobila, a ciliate which retains chloroplasts[J].Marine Biology, 1988, 99(3):415-423.

[15]Strom S L, Benner R, Ziegler S, et al.Planktonic grazers are a potentially important source of marine dissolved organic carbon[J].Limnology and Oceanography, 1997, 42(6): 1364-1374.

[16]Strom S L, Morello T A. Comparative growth rates and yields of ciliates and heterotrophic dinoflagellates[J].Journal of Plankton Research, 1998, 20(3): 571-584.

[17]Strom S L. Light-aided digestion, grazing and growth in herbivorous protists[J].Aquatic Microbial Ecology,2001, 23(3): 253-261.

[18]Strom S, Wolfe G, Holmes J, et al.Chemical defense in the microplankton I: Feeding and growth rates of heterotrophic protists on the DMS-producing phytoplankterEmiliania huxleyi[J].Limnology and Oceanography, 2003, 48(1): 217-229.

[19]Strom S L, Bright K J. Inter-strain differences in nitrogen use by the coccolithophoreEmiliania huxleyi,and consequences for predation by a planktonic ciliate[J].Harmful Algae, 2009, 8(5): 811-816.

[20]Rosetta C H, McManus G B. Feeding by ciliates on two harmful algal bloom species,Prymnesium parvumandProrocentrum minimum[J].Harmful Algae, 2003, 2(2):109-126.

[21]Gold K. Tintinnida-feeding experiments and lorica development[J].Journal of Protozoology, 1969, 16(3):507-509.

[22]Pedersen M F, Hansen P J. Effects of high pH on the growth and survival of six marine heterotrophic protists[J].Marine Ecology-Progress Series, 2003, 260: 33-41.

[23]Kleppel G S, Lessard E J. Carotenoid-pigments in microzooplankton[J].Marine Ecology-Progress Series,1992, 84(3): 211-218.

[24]Putt M. Metabolism of photosynthate in the chloroplast-retaining ciliateLaboea strobila[J].Marine Ecology-Progress Series, 1990, 60(3): 271-282.

[25]Jonsson P R. Particle-size selection, feeding rates and growth dynamics of marine planktonic oligotrichous ciliates (Ciliophora, Oligotrichina)[J].Marine Ecology-Progress Series, 1986, 33(3): 265-277.

[26]Kim J S, Jeong H J, Strueder-Kypke M C, et al.Parastrombidinopsis shimin. gen., n. sp. (Ciliophora:Choreotrichia) from the coastal waters of Korea:Morphology and small subunit ribosomal DNA sequence[J].Journal of Eukaryotic Microbiology, 2005,52(6): 514-522.

[27]Fredrickson K A, Strom S L. The algal osmolyte DMSP as a microzooplankton grazing deterrent in laboratory and field studies[J].Journal of Plankton Research, 2009,31(2): 135-152.

[28]Hansen F C, Reckermann M, Breteler W, et al.Phaeocystis blooming enhanced by copepod predation on protozoa-evidence from incubation experiments[J].Marine Ecology-Progress Series, 1993, 102(1-2):51-57.

[29]Lessard E J, Martin M P, Montagnes D J S. A new method for live-staining protists with DAPI and its application as a tracer of ingestion by walleye pollock(Theragra chalcogramma(Pallas)) larvae[J].Journal of Experimental Marine Biology and Ecology, 1996,204(1-2): 43-57.

[30]Bernard C, Rassoulzadegan F. Bacteria or microflagellates as a major food source for marine ciliatespossible implications for the microzooplankton[J].Marine Ecology-Progress Series, 1990, 64(1-2):147-155.

[31]类彦立, 徐奎栋. 单胞藻培养中一敌害纤毛虫——具沟急游虫的生态习性及形态学初探[J]. 中国水产科学, 1996, 3(4): 39-47.

[32]Gold K. Growth characteristics of mass-reared tintinnidTintinnopsis beroidea[J].Marine Biology, 1971, 8(2):105-108.

[33]Clough J, Strom S. Effects ofHeterosigma akashiwo(Raphidophyceae) on protist grazers: laboratory experiments with ciliates and heterotrophic dinoflagellates[J].Aquatic Microbial Ecology, 2005, 39(2): 121-134.

[34]Jakobsen H H, Strom S L. Circadian cycles in growth and feeding rates of heterotrophic protist plankton[J].Limnology and Oceanography, 2004, 49(6): 1915-1922.

[35]Montagnes D J S, Taylor F J R. The salient features of 5 marine ciliates in the class Spirotrichea (Oligotrichia),with notes on their culturing and behavior[J].Journal of Eukaryotic Microbiology, 1994, 41(6): 569-586.

[36]Guillard R R L, Ryther J H. Studies of marine planktonic diatoms. 1.Cyclotella nanaHustedt, andDetonula confervacea(cleve) Gran[J].Canadian Journal of Microbiology, 1962, 8(2): 229-239.

[37]Guillard R R L. Culture of Marine Invertebrate Animals[M]. New York: Plenum Press, 1975: 29-60.

[38]Tillmann U. Interactions between planktonic microalgae and protozoan grazers[J].Journal of Eukaryotic Microbiology, 2004, 51(2): 156-168.

[39]Gold K. Cultivation of marine ciliates (Tintinnida) and heterotrophic flagellates[J].Helgolander Wissenschaftliche Meeresuntersuchungen, 1970, 20(1-4): 264-271.

[40]Chen K M, Chang J. Influence of light intensity on the ingestion rate of a marine ciliate,Lohmanniellasp.[J].Journal of Plankton Research, 1999, 21(9): 1791-1798.

[41]Ohman M D, Snyder R A. Growth-kinetics of the omnivorous oligotrich ciliateStrombidiumsp.[J].Limnology and Oceanography, 1991, 36(5): 922-935.

[42]张武昌, 张翠霞, 肖天. 海洋浮游生态系统中小型浮游动物的生态功能[J].地球科学进展, 2009, 24(11):1195-1201.

Q958.8

A

1000-3096(2011)09-0119-05

2010-07-20;

2010-12-30

国家自然科学基金资助项目(40876085); 国家973计划项目(2011CB409804); 海洋公益性行业科研专项经费资助项目(200805042);国家海洋局海洋生态系统与海洋生物地球化学重点实验室开放基金资助项目(LMEB200803)

于莹(1986-), 女, 山东荣成人, 硕士研究生, 主要从事海洋浮游动物生态学, 电话: 0532-82898937, Email: yuyingxlf001@163.com

谭雪静)