你付了多少?:门票销售新点子

当你在对号入座的座位上花去的时间占据了清醒时刻的三分之一时——无论是在飞机机舱还是演出场地,难免会一时糊涂,把两者混淆。曾经有一次,我赶在临开场时冲进北京保利剧院的剧场里,但坐定下后的动作 却是把两手伸到座位下,寻觅机舱安全带。多年来,我发现座位礼仪的某些细节是全球性的。比如说,你从来不会告诉邻座的人,自己是花了多少钱弄到这张门票的。

想当年,一切都简单得多。门票上印有票价,也许是你花钱买的,也许是赠票。当然也有其他情况的存在:航空公司在淡季会提供机票折扣;而预先买剧院套票,主办方或许会给你打个八折。此外,上述的例子还存在着阶级制度,唯一的区别是,走进舱门后你需要看好是往左走还是往右走,而在剧场里,你需要留意是往下走还是往上走。可是这几年,这些惯例却变得一团糟。

大概20年前,航空公司与艺术团体不约而同地发现,观众们的购票准则是:钱花得越少越好,如果能获得免费赠票的话那更是再好不过了。当时,他们搞不清这一现象背后的本质原因:到底是纯粹的经济因素,还是涉及了消费阶层的问题。但他们的第一步措施很简单:大幅度降低票价。这个举措就算是最商业化的制作人都会同意,减少一点收入总要比剧场空空如也好得多。

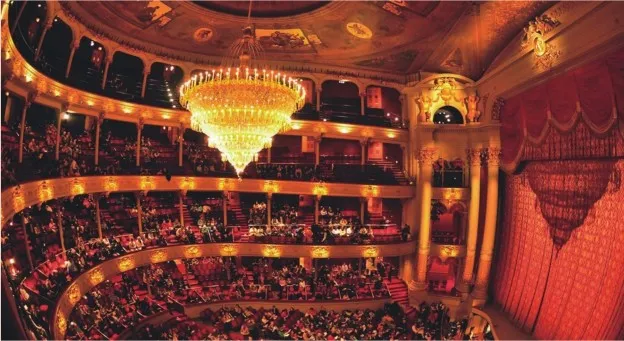

一些表演艺术行业的营销人员曾一度提议票价要走“大众路线”。“我们为什么不把歌剧院和音乐厅当作电影院来对待呢?”一位著名的推销顾问这样说,他提议统一剧场的票价,不设定票位区域,入场的观众先到先得——即使是在20年前,这个提议听起来也相当幼稚。不曾想到的是,后来电影院却效仿歌剧院与音乐厅,实行不同区域、不同座位的电影票售价不一。

更近一段时间,一个可行的方案浮出水面——“限时优惠票”(rush tickets,又名“速达票”):很多演出方或是某些航空公司,在剧目临演出或航班起飞前平价出售剩余的门票或机票。可是,大家很快就发现了这一举措的缺陷。我在纽约的邻居是大都会的铁粉,多年来一直会购买大都会歌剧院的套票。然而前几年票价飙升,连他们都吃不消,于是他们放弃了套票的那些好座位。也正因此,他们的观演日程变得灵活得多。大都会演出季开幕的当天刚好就有限时优惠票出售,他们立刻在网上抢购了两张。随后他们发现那两个座位正位于从前套票座位区的后两排,而他们付出的价钱却仅仅是套票的十分之一。

我敢肯定,灵机一动想出“限时优惠票”方案的那个人多半不在大都会歌剧院的销售部门工作,更不会是负责套票推销的那个人。这种一方面提高套票价格,另一方面又给零售票送上新折扣优惠的举措,实在是自相矛盾,让人摸不着头脑。如果可以临时买到便宜门票看戏,为什么要花大钱预先购票,而观演日程又被绑定受限呢?套票这个营销模式真的是濒临绝境了。试想下你想要登机,但是手里只有一张充了值的交通卡。

现在,去影院看电影的人越来越少,大部分人会选择家庭影院的模式。鉴于此,艺术团体开始鼓吹另外一种方案,模仿“网飞”(Netflix)计划——流媒体依靠会员预先缴纳会费为收入基础。顾名思义,这种模式就是让你先交纳每月或每年度的会费,就可以无限量观看演出。对于制作人与主办方来说,该计划的主要优点与套票相类似:早早地就将该笔费用收入囊中;对于观众来说,新计划避开了从前套票模式的缺点(必须提前安排好观剧日程,几乎没有任何回旋余地)。

这个计划可能成为全美最划算的——试想下,一整个演出季你都可以享用剧目的“饕餮自助”,但也可能成为最糟糕的营销案——如果提供的节目选择与演出时段不合适或者不够吸引人的话,可能就会一败涂地。倘若你觉得剧院这种高雅艺术与媚俗的商业互不相容,不妨换一个角度来看看:这是一个健身会所,而得益的是你的灵魂(我在新加坡的一位朋友就经常会埋怨,他的健身会所真是贵得要命,因为他工作太忙,一个月用不上几次)。

有些主办单位(尤其引人瞩目的是林肯中心)的某些演出推出了专为具有强烈阶级意识、寻找降价商品的观众特设的“随你付”计划。由著名高男高音安东尼·罗斯·科斯坦佐(Anthony Roth Costanzo)领导的费城歌剧院,为观众们送上11美元一口价的门票,更呼吁观众可以在购票的同时为剧院捐款。究竟观众们会不会真的为费城歌剧院慷慨解囊,我们拭目以待,但折扣购物并不是建立品牌忠诚度的好策略。

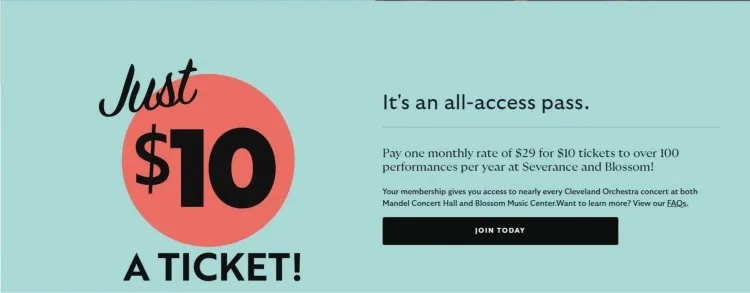

那么“会员制”呢?好吧,欢迎你参加。有几家美国交响乐团在疫情后开拓了新模式。众所周知,疫情令各大院团的上座率,特别是套票售出付出了惨痛代价。新模式是这样的:因为观众先付了“会员费”,他们的选择就更富冒险精神;乐团也一样,尤其是在策划新音乐曲目,或是制作更大胆的演出方面(这也是另一个可与“网飞计划”相提并论的原因,至少在流媒体时代的早期更是如此)。会员费的多少通常去取决于乐团的水平与当地文化背景:阿肯色州交响乐团(Arkansas Symphony Orchestra)每月收取9美元会员费,而克利夫兰乐团(Cleveland Orchestra)每月的会员费为29美元,会员可以无限量购买折扣门票,每张为10美元。

圣保罗室内乐团显然受到了航空业的启发,为观众提供不同价位的会员资格可选择,从每月5美元到20美元不等,不同的价格可选择不同的座位区域——可谓是剧院的“经济舱”至“头等舱”。至今,没有乐团胆敢说自己成功地制定出一个完美的方案。大家还在不断地微调方案中,但至少音乐厅的入座率提高了。

如果在新方案中有一个亏损者,那一定是票务部的员工:他们必须更具灵活性地调整固有的票务系统。数十年来,甚至是在技术发达的今天,大都会歌剧院的套票持有人,如果观演计划有变需要更换日期,需要办理的程序麻烦至极。可是眼看现下因为加价而套票滞销,外加观众蜂拥抢购便宜的“速达票”,票房收入可谓是雪上加霜,或许这就是一种因果报应。

When you spend up to a third of your waking hours in a ticketed seat, either in an airplane or a performance venue, you’re bound to get the two confused. I once found myself rushing down the aisle at the Poly Theatre in Beijing and reaching under the chair for the seatbelt. But over the years, I’ve noticed that certain bits of seating etiquette have become universal. For one thing, never mention to anyone around you how much—or how little—you paid for your ticket.

Back in the day, things were pretty simple. The ticket had a price on it, and you either paid or you didn’t. Some mitigating circumstances might occur: airlines could offer discounts during the off-season, and arts presenters would lop 20 percent off the face value if you paid upfront for a subscription bundle of shows. Also, both had a built-in class system, the only difference being that after entering a plane you turned right or left and in a theater you walked up or down. But for some time now, the situation has been a tangled mess.

Some 20 years ago, both airlines and theaters found that, faced with either paying or not, many people weren’t. What wasn’t immediately clear was whether the problem was strictly financial or if the class element was involved as well. The first step was obviously to slash ticket prices, since even the most commercial producers would agree that less revenue outweighed the prospects of empty seats.

Early on, some marketing folks in the performing arts had suggested playing the populist card. “Why don’t we just treat opera houses and concert halls like movie theaters?” one prominent consultant asked, suggesting that all tickets should have one standard price, with unassigned seating on a firstcome, first-served basis. That sounded rather na?ve even 20 years ago; now some movie theatres have gone the opposite direction, with dedicated seating and multiple ticket prices based on location.

More recently, a viable option has been the so- called “rush tickets,” offered by many arts presenters (and even a few airlines) to fill unsold seats at the last minute. But the downside here became obvious quite quickly. My New York neighbors, longtime fans of the Metropolitan Opera, gave up their treasured subscriptions when the prices skyrocketed beyond their budget. With their schedule now considerably freer, they pounced on a pair of rush tickets to the first show of the season. Their new seats were two rows behind their former seats, at less than 10 percent of the price.

I’m pretty sure whoever came up with the idea of rush tickets was not in the Met’s subscription department. Raising base prices at the same time you offer new discount possibilities definitely sends mixed signals. Why pay big bucks to tie yourself down to specific dates when you can get cheap tick-ets whenever you want? Anyone waiting for yet another nail in the coffin of subscription pricing need look no further. You might as well let people board a plane using a pre-paid travel card.

Now that fewer people are even going out to the movies, preferring to screen their films at home, performing arts presenters are already starting to embrace another model, dubbed “the Netflix plan”after streaming services that base their revenue on membership dues. Pay your monthly (or annual) fee and you can attend as many concerts as you like. For producers and presenters, it has the key advantage of subscriptions (getting the audience’s money upfront). For audiences, it avoids the old model’s disadvantages (having to plan so far in advance, with little room to maneuver).

It can be either the best deal in town, the equivalent of a season-long buffet dinner, or one of the worst, if few of the options or timings are appealing or convenient. If you find the idea of high art incompatible with such crass commerce, just think of it as a gym membership for the soul. (A friend in Singapore often complains that his gym there is the most expensive he’s ever seen, since he’s only able to make it there a couple of times a month.)

Some presenters (most notably, Lincoln Center) have offered their class-conscious, bargain-hunting fans a pay-what-you wish model for many of their offerings. Opera Philadelphia, now headed by countertenor Anthony Roth Costanzo, has started offering all tickets for US$11, with an option to donate more. Whether audiences actually do pay more remains to be seen. Discount shopping is not exactly a sound strategy for building brand loyalty.

But memberships? Well, welcome to the club. A handful of American orchestras have started cultivating a new model after the Covid pandemic, which took its toll on attendance in general and subscriptions in particular. Under the new model, audience members, having already paid their dues, became more adventurous with their choices; so too did the orchestras, particularly in presenting new music and more courageous programming (another reason for comparison to Netflix, at least in its early days of streaming). Membership fees often depend on both the quality of the orchestra and local culture: the Arkansas Symphony Orchestra costs US$9 a month, while the Cleveland Orchestra charges $29 a month in exchange for unlimited $10 tickets.

The Saint Paul Chamber Orchestra, perhaps tak-ing a cue from the airline industry, offers memberships at different price points, from $5 to $20 per month—from Economy to First Class, so to speak—with members allowed to choose their own seats within their fare class. None of these orchestras claims to have arrived yet at a perfect solution—they’re all still tweaking their models—but at least their concert halls are fuller.

If there’s a loser in this new structure, it’s the ticketing department, who needs to create more flexibility than the original system ever had. For decades—and perhaps even today—ticket holders at the Met had no recourse if their plans changed and they need to switch their dates. But considering the mass exodus among subscribers when rush tickets started, that’s the least the sales department deserves.