初诊双相障碍Ⅱ型抑郁发作患者认知功能改变及与临床特征的关系研究

何琛琛 高媛 张明霞 刘燕霞 孙守强

摘要:目的 探讨初诊双相障碍Ⅱ型抑郁发作患者认知功能改变及与临床特征的关系。方法 纳入2018年1月-2021年1月我院就诊初诊双相障碍Ⅱ型抑郁发作患者,以及同期招募的我院体检中心完善检查的健康人群各172例。比较两组一般资料、临床特征、精神分裂症认知功能评估成套测验认知功能评分(MCCB)及认知功能损伤发生率,并进一步评价患者临床症状与认知功能间相关性。结果 两组性别、年龄及受教育年限比较,差异无统计学意义(P>0.05);观察组 HAMD24量表总分高于对照组(P<0.05);观察组信息处理评分、注意力警觉评分、工作记忆评分、词语学习评分、视觉学习评分、推理与问题解决评分、社会认知评分及MCCB量表总分低于对照组(P<0.05);观察组低于1个、1.5个及2个标准差MCCB量表评分比例均高于对照组(P<0.05);相关性分析结果显示,患者词语学习能力、推理与问题解决能力评分均与抑郁发作次数存在负相关关系(P<0.05);年龄、受教育年限、发作次数、总病程及HAMD24总分与MCCB量表评分间无相关性(P>0.05)。结论 初诊双相障碍Ⅱ型抑郁发作患者认知功能改变与抑郁发作次数密切相关。

关键词:双相情感障碍;抑郁发作;认知功能;临床特征

中图分类号:R749.4 文献标识码:A DOI:10.3969/j.issn.1006-1959.2024.11.013

文章编号:1006-1959(2024)11-0074-05

Study on the Changes of Cognitive Function and its Relationship with Clinical Characteristics

in Patients with Newly Diagnosed Bipolar Disorder Type Ⅱ Depressive Episode

Abstract:Objective To investigate the changes of cognitive function in patients with newly diagnosed bipolar disorder type Ⅱ depressive episode and its relationship with clinical characteristics.Methods From January 2018 to January 2021, 172 patients with newly diagnosed bipolar disorder type Ⅱ depressive episode and 172 healthy people who were recruited in the physical examination center of our hospital during the same period were included. The general data, clinical characteristics, MATRICS Consensus Cognitive Battery(MCCB) and the incidence of cognitive impairment were compared between the two groups, and the correlation between clinical symptoms and cognitive function was further evaluated.Results There was no significant difference in gender, age and years of education between the two groups (P>0.05). The total score of HAMD24 scale in the observation group was higher than that in the control group (P<0.05). The information processing score, attention alertness score, working memory score, word learning score, visual learning score, reasoning and problem solving score, social cognitive score and MCCB total score of the observation group were lower than those of the control group (P<0.05). The proportion of MCCB scale scores lower than 1, 1.5 and 2 standard deviations in the observation group was higher than that in the control group (P<0.05). The results of correlation analysis showed that the scores of patients' word learning ability, reasoning and problem solving ability were negatively correlated with the number of depressive episodes (P<0.05). There was no correlation between age, years of education, number of episodes, total course of disease and HAMD24 total score and MCCB scale score (P>0.05).Conclusion The changes of cognitive function in patients with newly diagnosed bipolar disorder type Ⅱ depressive episode are closely related to the number of depressive episodes.

Key words:Bipolar disorder;Depressive episode;Cognitive function;Clinical characteristics

Ⅱ型双相情感障碍患者主要临床特征为心境不稳,存在躁狂、轻度躁狂发作或重度抑郁发作等症状[1];而认知功能损伤被认为是该病患者核心临床症状,与情感症状独立存在,故单纯改善情绪症状往往难以有效促进生活工作质量恢复,这一比例超过60%[2]。如何协助双相情感障碍患者最大限度实现认知痊愈越来越受到关注。但在临床实践过程中仅不足40%的双相情感障碍患者检测认知功能,且情感障碍患者认知损害症状评估缺乏统一标准[3]。有报道将认知功能损伤定位为≥2个认知领域得分下降1~2个标准差,但因纳入人群和评定标准不统一导致研究结果存在较大差异[4]。基于以上证据,本研究通过分析初诊双相障碍Ⅱ型抑郁发作患者认知功能改变及与临床特征的关系,旨在为后续认知干预方案及个体化治疗方案制定提供更多参考,现报道如下。

1资料与方法

1.1一般资料 纳入2018年1月-2021年1月于国药东风茅箭医院/十堰市精神病医院就诊初诊双相障碍Ⅱ型抑郁发作患者(观察组),另同期招募我院体检中心完善检查的健康人群(对照组),各172例。研究方案经我院伦理委员会批准,研究对象知情同意并签署同意书。

1.2纳入与排除标准 观察组纳入标准:①由两名中级及以上职称的高年资医师评估符合DSM-5诊断标准[5];②首次诊断;③年龄18~60岁;④基线HAMD24评分≥20分,且基线YMRS评分<6分;⑤汉族;⑥右利手;⑦初中及以上文化水平。排除标准:①合并其他精神系统疾病;②合并混合特征或其他类型双相情感障碍;③脑部器质性疾病史或脑外伤史;④严重躯体疾病;⑤酗酒或药物滥用;⑥近6个月接受电休克治疗;⑦妊娠或哺乳期女性。对照组纳入标准:①经体检证实身体健康;②基线HAMD24评分<8分,且基线YMRS评分<6分;③年龄18~60岁;④汉族;⑤右利手;⑥初中及以上文化水平。排除标准:①精神系统疾病或家族史;②脑部器质性疾病史或脑外伤史;③严重躯体疾病;④酗酒或药物滥用;⑤妊娠或哺乳期女性。

1.3方法 收集研究对象一般资料,包括年龄、性别、受教育时间、抑郁发作次数、病程及家族史。抑郁症状严重程度评估采用HAMD24量表,共24个条目,每个条目0~4分,分值越高提示抑郁症状越严重[6]。认知功能评估采用MCCB量表,包括信息处理评分、注意力警觉评分、工作记忆评分、词语学习评分、视觉学习评分、推理与问题解决评分、社会认知评分7部分,原始分数经中国常模转换为T分计算总分[6]。认知损伤发生判定标准:以MCCB量表评分50分为均数,10分为1个标准差,低于标准值1、1.5及2个标准差即可判定,MCCB评分包含7个维度共计10项条目,每项条目分值转换后标准分之和即为MCCB总分(100分),总分越低代表认知功能越差[6]。YMRS评分包括11个条目,其中第1、2、3、4、7、10、11个条目分值0~4分,其余条目分值0~8分,≥6分判定为存在躁狂症状,分值越高提示躁狂越严重。

1.4统计学方法 采用SPSS 18.0软件处理数据,正态性评估采用Levene检验,其中符合正态分布计量资料比较采用t检验,以(x±s)表示。计数资料比较采用χ2检验法,以[n(%)]表示;采用Spearman检验评价临床特征与认知功能损伤间相关性,P<0.05为差异有统计学意义。

2结果

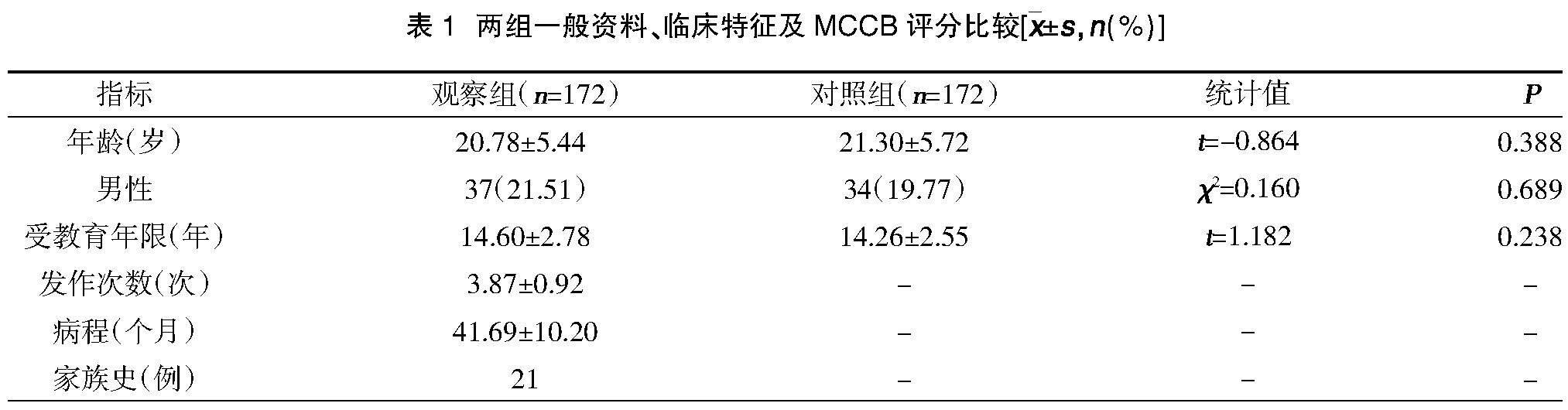

2.1两组一般资料、临床特征及MCCB评分比较 两组性别、年龄、受教育年限、YMRS评分比较,差异无统计学意义(P>0.05);观察组HAMD24量表总分高于对照组,差异有统计学意义(P<0.05);观察组信息处理评分、注意力警觉评分、工作记忆评分、词语学习评分、视觉学习评分、推理与问题解决评分、社会认知评分及MCCB量表总分低于对照组,差异有统计学意义(P<0.05),见表1。

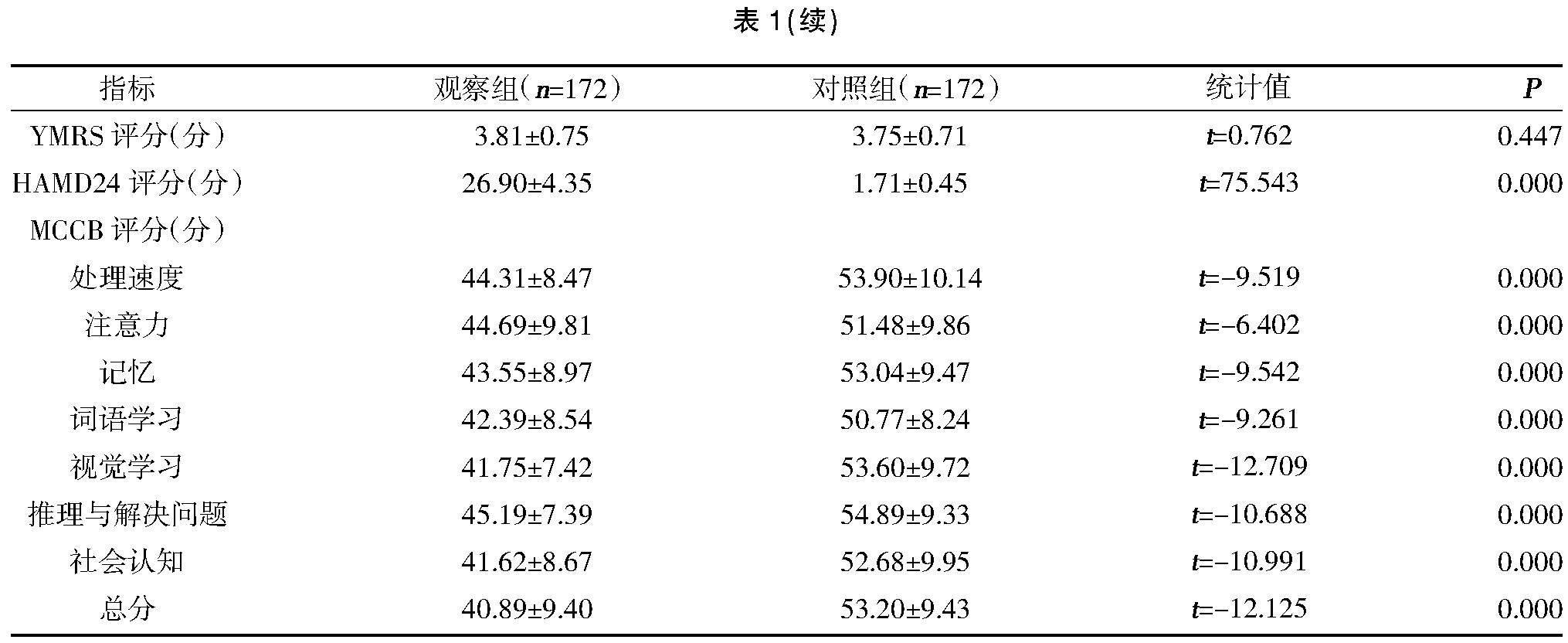

2.2两组认知功能损伤发生率比较 观察组低于1个、1.5个及2个标准差MCCB量表评分比例均高于对照组,差异有统计学意义(P<0.05),见表2。

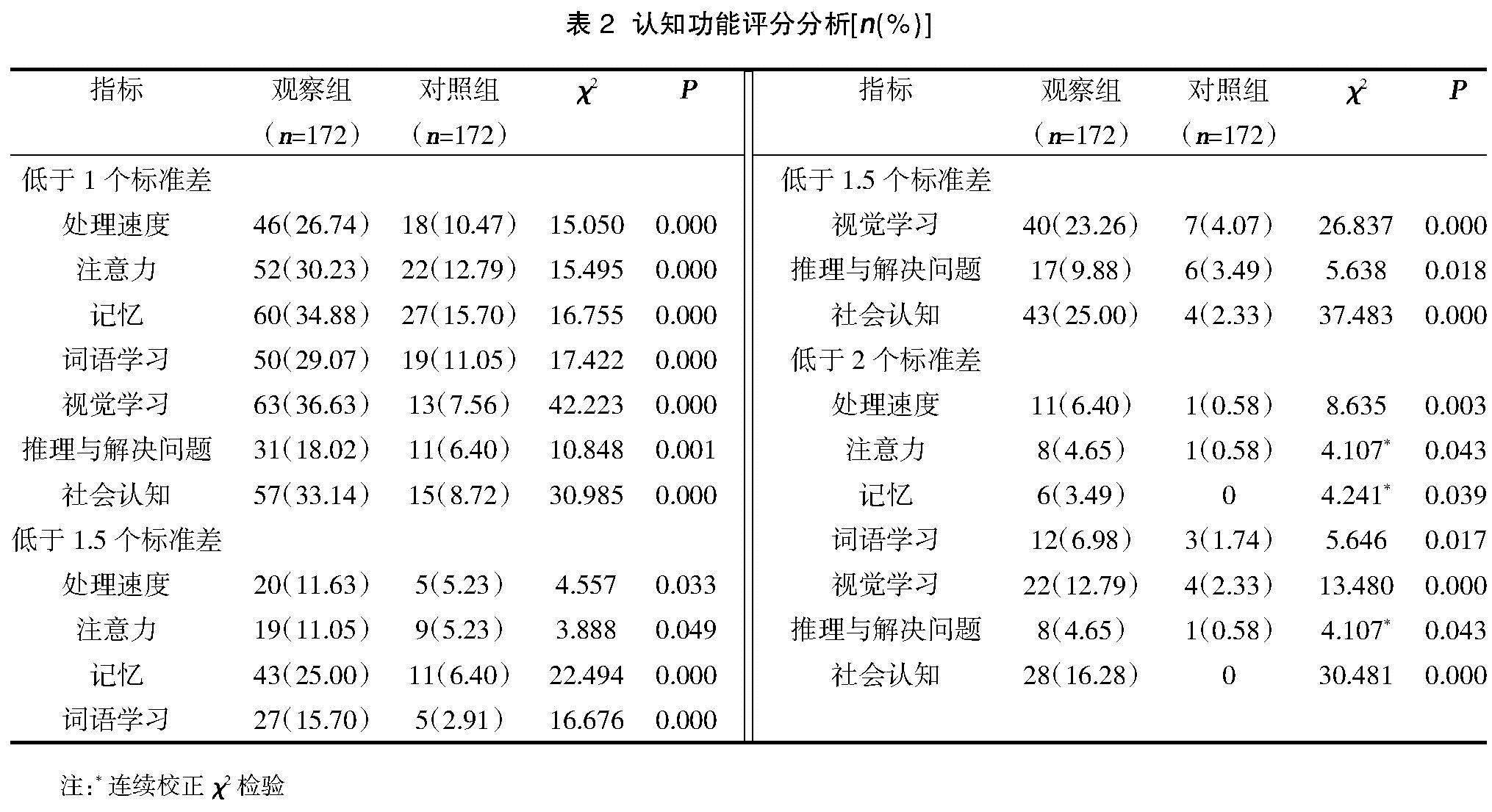

2.3患者临床特征与MCCB评分间相关性分析 相关性分析结果显示,患者词语学习能力、推理与问题解决能力评分均与抑郁发作次数存在负相关关系(P<0.05);年龄、受教育年限、发作次数、总病程及HAMD24总分与MCCB量表评分间无相关性(P>0.05),见表3。

3讨论

研究显示[7,8],Ⅱ型双相情感障碍患者往往伴有视觉、学习及记忆能力损伤等问题,其中合并抑郁人群在视觉等信息处理方面障碍更为显著,这可能与脑皮质信息存储、刷新及加工容量缩小有关。本次研究结果中,观察组低于1个、1.5个及2个标准差MCCB量表评分比例均高于对照组(P<0.05),提示初诊双相障碍Ⅱ型抑郁发作患者在多个认知领域均可见明显损伤,与以往报道结果相符[9]。其中以<1.5个标准值作为认知功能损伤判定标准时,患者以记忆和社会认知损伤最为常见;而以<2个标准值作为判定标准时,则损伤主要表现在视觉学习和社会认知两方面,进一步证实此类患者存在较为严重认知领域损伤。临床诊疗过程中相当部分初诊双相障碍Ⅱ型抑郁发作患者尽管可观察到明显情绪症状缓解,但仍难以实现正常生活工作,造成这一现象可能原因即为潜在社会认知功能异常[10]。

本次研究显示,初诊双相障碍Ⅱ型抑郁发作患者MCCB量表评分低于正常水平0.5~1.2个标准差,与以往研究报道结果基本相符[11]。将<1.5个标准值作为认知功能损伤判定标准情况下,双相情感障碍患者认知功能损伤发生率为18%~42%,而体检健康人群这一比例仅为2%,本次研究亦支持上述结果。而将<2个标准值作为认知功能损伤判定标准情况下,有报道显示35%双相情感障碍患者存在≥2个认知领域受损,而体检健康人群这一比例仅为3%[12]。另一项研究中7%急性期双相情感障碍患者存在认知功能损伤,而缓解期这一比例达11%[13];采用这一标准本次研究纳入初诊双相障碍Ⅱ型抑郁发作患者认知功能损伤率达14%,而体检健康人群无认知功能损伤病例。本次研究纳入患者认知功能损伤比例与以往报道仍存在一定差异,这可能与以往研究中纳入I型双相情感障碍或Ⅱ型双相情感障碍缓解期病例,且部分患者接受相应治疗有关[14]。此外,早期研究所采用认知功能评估工具并不统一,多为单独或几个量表联合[15],而本次研究采用MCCB量表评估更具临床推广应用价值。

本次研究进一步探讨初诊双相障碍Ⅱ型抑郁发作患者临床特征与认知功能损伤间的相关性,最终结果显示患者词语学习能力、推理与问题解决能力评分均与抑郁发作次数存在负相关关系(P<0.05);年龄、受教育年限、发作次数、总病程及HAMD24总分与MCCB量表评分间无相关性(P>0.05)。有报道显示[16],无论躁狂发作抑或抑郁发作双相情感障碍患者,发作次数越多则注意力和记忆力下降越明显,同时躁狂发作次数与言语学习能力存在负相关关系。另有研究指出抑郁发作相较于躁狂或混合性发作次数与认知功能缺损关系更为密切最密切,这可能与外周血中促炎细胞因子表达对于患者情绪症状发作及执行功能损伤的影响有关[17]。

MCCB量表是现有较为全面认知领域能力测评工具。但有报道显示[18,19],MCCB评估推理与解决问题分量表Cohen′s D=0.65,而WCST测验、Stroop 色词测验或TMT-B测验相较于该分量表往往更加敏感,其中WSCT和TMT-B测验Cohen′s D分别达0.73,0.86。故后续研究除可选择MCCB量表,更增加了联合WCST、TMT-B等测验工具提高部分认知功能损伤特征评估效能。

综上所述,初诊双相障碍Ⅱ型抑郁发作患者认知功能改变与抑郁发作次数密切相关。

参考文献:

[1]El Nagar Z,El Shahawi HH,Effat SM,et al.Single episode brief psychotic disorder versus bipolar disorder: A diffusion tensor imaging and executive functions study[J].Schizophr Res Cogn,2021,27(9):100214.

[2]Xu X,Xiang H,Qiu Y,et al.Sex differences in cognitive function of first-diagnosed and drug-naive patients with bipolar disorder[J].J Affect Disord,2021,295(9):431-437.

[3]Huang Y,Wang Y,Wang H,et al.Prevalence of mental disorders in China: a cross-sectional epidemiological study[J].Lancet Psychiatry,2019,6(3):211-224.

[4]Bomyea JA,Parrish EM,Paolillo EW,et al.Relationships between daily mood states and real-time cognitive performance in individuals with bipolar disorder and healthy comparators: A remote ambulatory assessment study[J].J Clin Exp Neuropsychol,2021,8(9):1-12.

[5]汪作为,马燕桃,陈俊,等.中国双相障碍防治指南:基于循证的选择[J].中华精神科杂志,2017,50(2):96-100.

[6]Simjanoski M,McIntyre A,Kapczinski F,et al.Cognitive impairment in bipolar disorder in comparison to mild cognitive impairment and dementia: a systematic review[J].Trends Psychiatry Psychother,2021,9(8):1152-1159.

[7]Simjanoski M,Jansen K,Mondin TC,et al.Cognitive complaints in individuals recently diagnosed with bipolar disorder: A cross-sectional study[J].Psychiatry Res,2021,300(6):113894.

[8]Simonetti A,Kurian S,Saxena J,et al.Cognitive correlates of impulsive aggression in youth with pediatric bipolar disorder and bipolar offspring[J].J Affect Disord,2021,287(5):387-396.

[9]Douglas KM,Gallagher P,Robinson LJ,et al.Prevalence of cognitive impairment in major depression and bipolar disorder[J].Bipolar Disord,2018,20(3):260-274.

[10]Petersen JZ,Macoveanu J,Kj?rstad HL,et al.Assessment of the neuronal underpinnings of cognitive impairment in bipolar disorder with a picture encoding paradigm and methodological lessons learnt[J].J Psychopharmacol,2021,35(8):983-991.

[11]Miskowiak KW,Jespersen AE,Obenhausen K,et al.Internet-based cognitive assessment tool: Sensitivity and validity of a new online cognition screening tool for patients with bipolar disorder[J].J Affect Disord,2021,289(6):125-134.

[12]Liu T,Zhong S,Wang B,et al.Similar profiles of cognitive domain deficits between medication-na?ve patients with bipolar Ⅱ depression and those with major depressive disorder[J].J Affect Disord,2019,243(10):55-61.

[13]Ribera C,Vidal-Rubio SL,Romeu-Climent JE,et al.Cognitive impairment and consumption of mental healthcare resources in outpatients with bipolar disorder[J].J Psychiatr Res,2021,138(6):535-540.

[14]Callahan BL,McLaren-Gradinaru M,Burles F,et al.How Does Dementia Begin to Manifest in Bipolar Disorder? A Description of Prodromal Clinical and Cognitive Changes[J].J Alzheimers Dis,2021,82(2):737-748.

[15]Beunders AJM,Kemp T,Korten NCM,et al.Cognitive performance in older-age bipolar disorder: Investigating psychiatric characteristics, cardiovascular burden and psychotropic medication[J].Acta Psychiatr Scand,2021,144(4):392-406.

[16]Macoveanu J,Freeman KO,Kjaerstad HL,et al.Structural brain abnormalities associated with cognitive impairments in bipolar disorder[J].Acta Psychiatr Scand,2021,144(4):379-391.

[17]Burdick KE,Millett CE.Cognitive heterogeneity is a key predictor of differential functional outcome in patients with bipolar disorder[J].Eur Neuropsychopharmacol,2021,53(7):4-6.

[18]Millett CE,Harder J,Locascio JJ,et al.TNF-α and its soluble receptors mediate the relationship between prior severe mood episodes and cognitive dysfunction in euthymic bipolar disorder[J].Brain Behav Immun,2020,88(7):403-410.

[19]Tsapekos D,Strawbridge R,Cella M,et al.Cognitive impairment in euthymic patients with bipolar disorder: Prevalence estimation and model selection for predictors of cognitive performance[J].J Affect Disord,2021,294(11):497-504.