Resisting Economic Coercion

ROBERT WALKER

Unilateral sanctions have been imposed againstChina since 2017. They are illegal and shouldbe removed – so said the United Nations SpecialRapporteur on her recent visit of China.

PROFESSOR Alena Douhan is a Special Rapporteurfor the United Nations and a humanrights lawyer. She visited China in May aspart of her mandate to investigate the humanitarianconsequences of the unilateral coercivemeasures imposed on China. “Unilateral coercivemeasures” are what other people tend to call sanctions– or trade embargoes or punitive tariffs.

During her visit, Professor Douhan met governmentofficials, representatives of the legislative andjudicial branches, members of the diplomatic communityand academia, and stakeholders from businessand non-governmental organisations.

Her conclusion – at a final press conference in Beijing– was unequivocal: “States should lift sanctions against China.” They should also “take strong actionto curb sanction over-compliance by businesses andother actors under their jurisdiction.” Fearful of theunknown costs and penalties associated with sanctions,people overreact to them, exacerbating theirhumanitarian consequences.

Professor Douhan listed the direct and indirect effectsof sanctions: “Decline in business activities andthe significant loss of global markets, ... job losses,with consequent disruptions in social protectionschemes.” She said that the most vulnerable were disproportionatelyaffected: “women, older persons, andall those in informal employment.”

When Donald Trump was elected U.S. president,he declared, in his inaugural address, that “from thisday forward, its going to be only America first!”

His gripe was that “weve made other countries rich while the wealth … has dissipated over the horizon… One by one, the factories shuttered and leftour shores.”

not just

It is not justtariffs that theU.S. has implemented,seeminglyto holdback Chinasdevelopment.

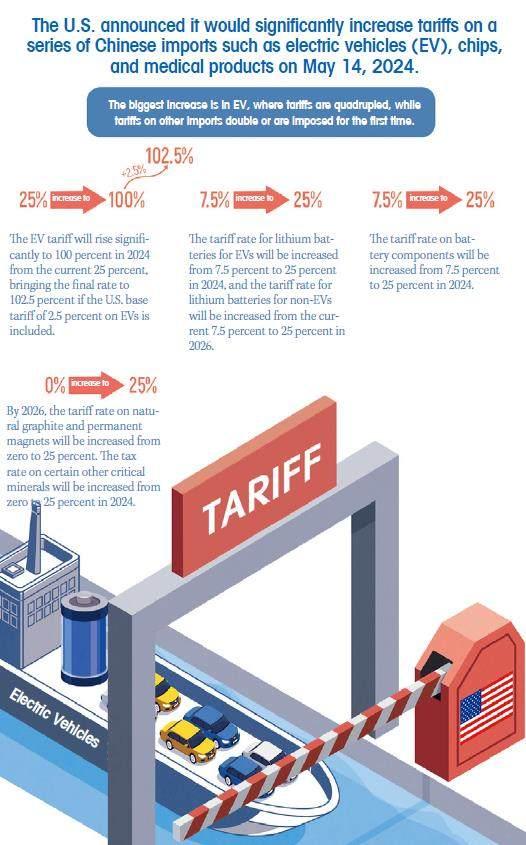

He reacted by imposing import tariffs of 25 percenton steel imports and 10 percent on aluminium.China responded by defensively imposing tariffs on128 products. The next day the U.S. announced tariffson more than 1,300 different kinds of Chinese goods.

It is not just tariffs that the U.S. has implemented,seemingly to hold back Chinas development. Chinesecompanies have been singled out and prevented fromtrading in the U.S. or with U.S. companies or, contentiously,with enterprises of other countries. Chinesepublic officials and other citizens have been named,their assets in the United States frozen, and theirglobal travel curtailed.

It is not often realized that these sanctions arebased on U.S. domestic legislation which legislatorshave determined should have force in other countriesand be subject to U.S. litigation. This is termed “extraterritoriality.”

The reasons given for these unilateral actionshave been various and often unspecific. Chinesecompanies have been accused of trading with Iranand Russia. Individuals have been sanctioned for “underminingHong Kongs autonomy.” Many Chinesecompanies and individuals have been sanctioned foralleged human rights abuses in Xinjiang.

Sanctions can be imposed without definitive evidence,based on assertion. In conflict with naturaljustice, to escape sanctions victims must prove thatthey have done nothing wrong. And this can only bedone through recourse to the U.S. legal system or U.S.administrative procedures – extraterritoriality again.

If all this seems unfair, then the United NationsHuman Rights Council would agree. In Resolution27/21, they call “upon all States to stop adopting,maintaining or implementing unilateral coercivemeasures not in accordance with international law.”

This raises the question of whether the measuresimposed on China are lawful. But, before addressingthis question, it is important to explain why the UNHuman Rights Council should be interested in thistopic.

One reason is that unilateral coercive measureshave negative humanitarian consequences. U.S. sanctionson Venezuela curtailed food imports, creating malnutrition for around 20 percent of under fiveyear-olds. Ratcheting up sanctions on North Korea in2017 is estimated to have caused 1,900 deaths.

Moreover, as the American scholar Ethan Kesslerexplains, some humanitarian suffering has been intentionallyengineered by the U.S.; it was anticipatedthat sanctions against Cuba in 1960 and Iran in 2010would cause social distress to foment political protesttoppling their respective governments.

The research evidence also demonstrates thatsanctions, especially those imposed unilaterally, arerarely effective in changing the behaviour of governments.Even so-called “smart sanctions” aimed atknown culprits, implemented with UN approval,negatively affect those targeted only 10 percent of thetime, according to analysis published in the Journalof Peace Research.

What sanctions can do is to degrade economies –even when this is not intended. This is demonstratedby a large scale study, published in the EuropeanJournal of Political Economy , covering 160 countriesof which 67 were sanctioned between 1976 and 2012.The GDP (gross domestic product) of countries targetedcharacteristically fell by two percent annuallyand by 25 percent over 10 years.

Syrias economy declined by 57 percent between2010 and 2015. Moreover, modelling suggests thesanctions impact on GDP quickly, and that economiestypically fail to fully recover.

Kessler advises governments wanting sanctions to be effective to target weak states. China, of course,is not a weak state either politically or economically.The robustness of Chinas economy makes it difficultto determine the negative consequences of U.S. sanctions.

Chinas cutting-edge industries have been targeted.As such, sanctions are likely to slow rates ofrecruitment of highly skilled personnel, adding to unemploymentamong recent graduates and reducingwage growth.

The concentration of hi-tech industries in moredensely populated urban areas will have localizednegative impacts. Not only component manufacturerswill be affected, but also local retail sectors thatservice the consumption needs of hi-tech employees.

This, in turn, will have impact on migrant workers,cutting remittances, and placing a brake on therevitalization of rural areas. These spatial multipliereffects, though difficult to measure, are likely to bereal.

Returning to the matter of legality, the InternationalLaw Commission has prepared a set of articles onthe responsibility of states for internationally wrongfulacts, the ARSIWA. Among the legitimate uses ofsanctions are the prevention of war, the protectionof human rights, hindrance of the proliferation of nuclearand mass-destructive weapons, the restorationof sovereignty, and the freeing of kidnapped citizens.Sanctions can also be used in retaliation providedthat the response is proportional.

Sanctions should not be employed in pursuit ofregime change or to alter the government structuresof another state. That would contravene the longestablishedright to national sovereignty. Nor shouldsanctions be punitive.

Sanctions must also be justifiable on a case-bycasebasis and prescribe the precise conditions underwhich the target nation or individual can be “desanctioned”and the sanctions removed.

The reasoning behind the initial imposition andcontinuation of unilateral tariffs by the U.S. is explainedin an official government report publishedlast year, the 2022 Report to Congress on ChinasWTO Compliance. It explains that the U.S. cannot accept“Chinas state-led, non-market approach to theeconomy and trade” and sought “solutions independentof the WTO.” The WTO is the intergovernmentalbody established in 1995 to mediate international trade disputes.

The same report explains how the U.S. “launchedan investigation into Chinas acts, policies and practicesrelating to technology transfer, intellectualproperty and innovation” and that “this investigationled to substantial U.S. tariffs on imports from China.”

The 2021 Strategic Competition Act similarly refersto “the challenges posed by the Peoples Republicof China (PRC) to our [U.S.] national and economicsecurity.”

Legal textbooks do not cite economic competitionas a valid reason for the imposition of sanctions. Yetthe U.S. would appear to be using domestic legislationto ensure that economic competitors are defeatedso that U.S. “economic security” is assured.

Sanctions imposed by the U.S. for “underminingHong Kongs autonomy” smack of an illicit attemptat regime change. While this might seem farfetched,it is difficult to believe that U.S. attachment to theconcept of “liberal democracy” was not a motivation.

China has frequently refuted accusations of humanrights abuses occurring in Xinjiang, notably inits 2022 report to the UN High Commissioner forHuman Rights. Yet, in March this year, the U.S. wasenforcing 117 punitive sanctions against 95 Xinjiangcompanies, officials, and government agencies.

The centrality of Xinjiang to Chinas leadership ofgreen technology, and its location as a gateway tothe Belt and Road corridors, raises suspicions thatthe human rights sanctions imposed on local entitieshave more to do with geoeconomics than with theprotection of human rights.

It is unlikely, therefore, that the U.S. sanctions arelegal whereas Chinas proportionate response appearsto be consistent with ARSIWA requirements.

Conversations suggest that many Chinese peopleno longer see the U.S. as a trusted business or researchpartner. This is likely to weaken global collaborationand prevent further development of an opentrading environment that can deliver sustainablegrowth, increase global incomes and enhance humanwellbeing. Increasingly people also view global politicswith suspicion and fear.

Should protectionist U.S. strategists attribute thisto the success of sanctions, a weakened adversary,they risk a world more dangerously divided than italready is. As a minimum, it is imperative to modernize international dispute settlement mechanisms toprevent trade and ideological differences escalatinginto economic warfare.

Better still, the world should unite behind HumanRights Council Resolution 27/21 and abolish the unlawfuluse of sanctions.

ROBERT WALKER is professor emeritus and emeritus fellow ofGreen Templeton College, University of Oxford. He is associatedwith the Jingshi Academy at Beijing Normal University andis also a fellow of the Royal Society of Arts and the Academy ofSocial Sciences in the U.K.