East Meets West: A Study of Maritime Silk Road Trade from the 8th to the Early 13th Century

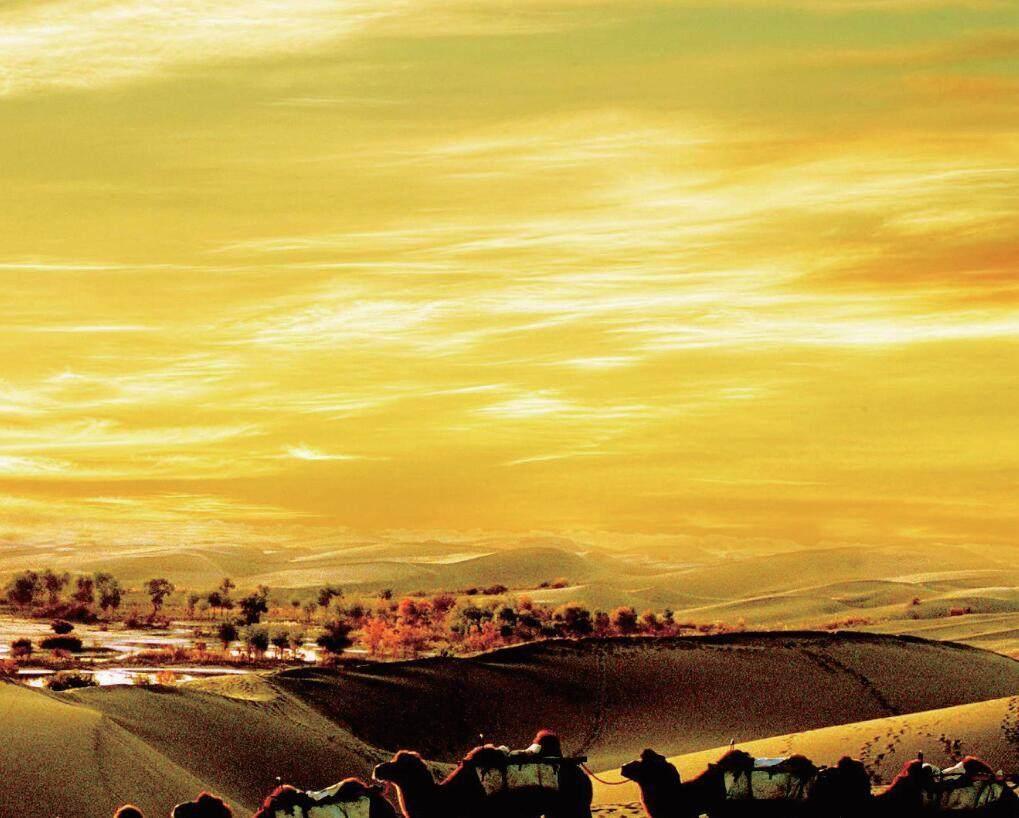

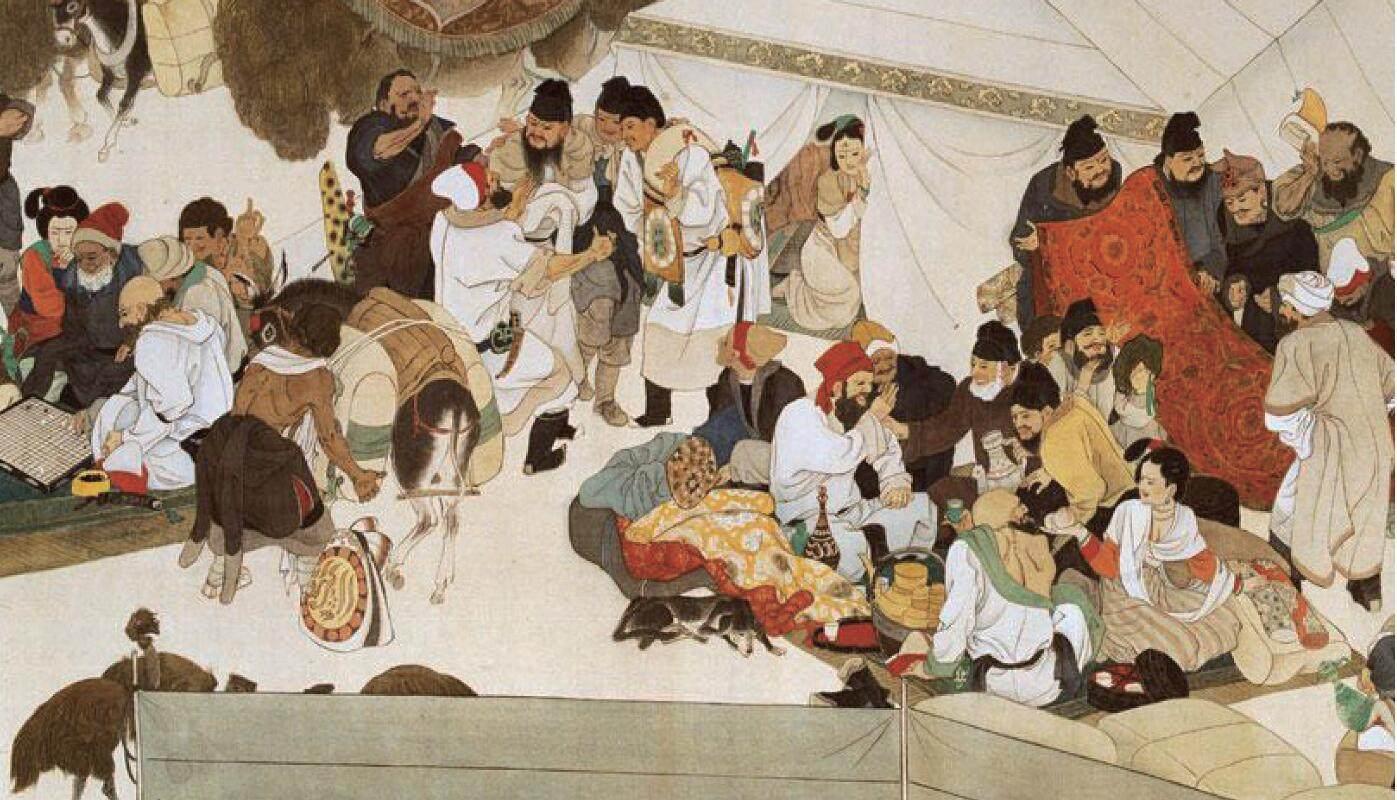

Drawing on detailed hand-me-down documents, modern inscriptions and commercial documents, and archaeological data handed down, the author attempts to break the traditional historical view of dynastic history and examine the long-term historical development of the Maritime Silk Road from the perspective of merchants traveling from the east to the west from the beginning of the 13th century.

East Meets West: A Study of Maritime Silk Road Trade from the 8th to the Early 13th Century

Chen Yexuan

Social Science Academic Press (China)

November 2023

128.00 (CNY)

Chen Yexuan

Chen Yexuan holds a PhD in History, and is currently a postdoctoral fellow in the Department of History, Peking University. His research interests include the history of ancient Sino-foreign relations and the history of the Sui and Tang dynasties. He has published many papers in various journals.

The earliest known Chinese envoy to the Abbasid Caliphate was the Yang Liangyao mission during the Zhenyuan Era of Emperor Dezong of the Tang Dynasty, as recorded in the Inscription of Yang Liangyaos Spirit Way. Mr. Rong Xinjiang surmises, “As an official envoy of the Tang Dynasty, Yang Liangyao would likely have chosen to use the dynastys ships.” So, what did Yang Liangyaos sailboat look like? The Inscription of Yang Liangyaos Spirit Way provides only this basic description of Yang Liangyaos sea voyage: “Raising sails to cut through the mist-filled air, rowing across the vast expanse of water. By night, guided by divine lamps for direction. By day, led forward by mythical beasts.” These four lines are all that describe Yang Liangyaos sailboat.

Mr. Rong points out that the “divine lamps guide the way” closely mirrors the description in the Geographical Records of the New Tang Book, which references Jia Dans Record of the Four Reaches of the Emperors Reign, about lighthouses in Djerrarah (present-day Irans Ubulla) where “locals erect sea markers, lighting torches on them at night, guiding ships and preventing sailors from getting lost.” This aligns with Yang Liangyaos personal experiences. Thus, the “divine lamps” likely refer to lighthouses seen in the Persian Gulf, a reasonable conjecture. The Buddhist stupas along Chinas southeastern coast had a similar function during the Southern Song Dynasty, as noted by Shi Liaoxin in the Reconstruction of the South Summit Pagoda Record, where it mentions the South Summit Pagoda by Hangzhous West Lake: “Lamps are hung under the eaves during each patrol, and whether on pitch-black rainy nights, sea merchants and mountain travelers alike use this tower as their guiding compass.” This indicates that lighthouses existed along both the eastern and western sections of the Maritime Silk Road. In the context of the Inscription of Yang Liangyaos Spirit Way, the phrases “By night, guided by divine lamps for direction; by day, led forward by mythical beasts” likely describe the scene of Yang Liangyaos fleet sailing under the guidance of lighthouses at night and being protected by divine power during the day. This is a more reasonable interpretation.

Of course, in the literature of Chinese naval history, “divine lamps” and “mythical beasts” are fundamental elements of ships. Zhang Hengs Rhapsody on the Western Capital mentions, “The bow is adorned with the figure of an egret, shadowed by the presence of orchid grass,” with Li Shans commentary explaining, “The bow is adorned with the shape of an egret, symbolizing the repulsion of water spirits. Hence, it is a vessel befitting the emperors use.” Gao Buyin of the Qing Dynasty notes, “The egret is a large bird. Its likeness painted on the bow leads to the designation ‘egret head.” The Illustrated Account of the Mission to Korea During the Xuanhe Era describes a divine ship from the late Northern Song Dynasty as “Majestic as mountains and floating atop the waves, the ship boasts brocaded sails and an egret-shaped bow, subduing the dragons and serpents of the water.” Gu Kaizhis Nymph of the Luo River painting also features a twin-hulled ship with mythical beasts painted on the bow. In the fifty-eighth year of the Kangxi Era (1719), Xu Baoguangs Records of Messages to Zhongshan includes an enclosed boat drawing with a mythical beast pattern, serving as a “Plaque of Exemption from Court Appearance.” This pattern has a long history in Chinese sailboat design. The mythical beast pattern, painted on the bow, corresponds to the description of the “led by mythical beasts” in the Spirit Way Inscription.

Divine lamps, on the other hand, were placed at the stern of traditional Chinese wooden sailboats. Gu Kaizhis Nymph of the Luo River painting features a lighthouse. In the sixth year of the Ming Xuande Era (1431), the stone inscription of the Record of Barbarian Tributes at Liujia Port, Loudong, to the Heavenly Consort Temple by Zheng He and others states, “Upon encountering danger and obstacles, merely invoking the name of the deity ensures an immediate response, and then a divine lamp will light up on the mast.” The Records of Messages to Zhongshan attached boat drawing shows the “divine lamp” located above the shrine at the stern tower. The enclosed boat, carrying the imperial edicts of the Qing emperor, had personnel specifically responsible for divine matters, according to Volume One of the Records of Messages to Zhongshan: “A person in charge of incense duties, primarily responsible for maintaining the oil lamps in front of the Heavenly Consort and various water deities statues, offering papers at sea every morning and evening, and managing the affairs at the stern of the large sailboat.” In Yang Liangyaos time, the Mazu faith had not yet emerged, and Yang Liangyao had worshiped the South Sea god, hence possibly requesting divine lamps from the temple.

Wang Guanzhuos Atlas of Ancient Chinese Ships reproduces the above-mentioned twin-hulled ship and enclosed boat drawings, offering clear illustrations. Marked as follows.