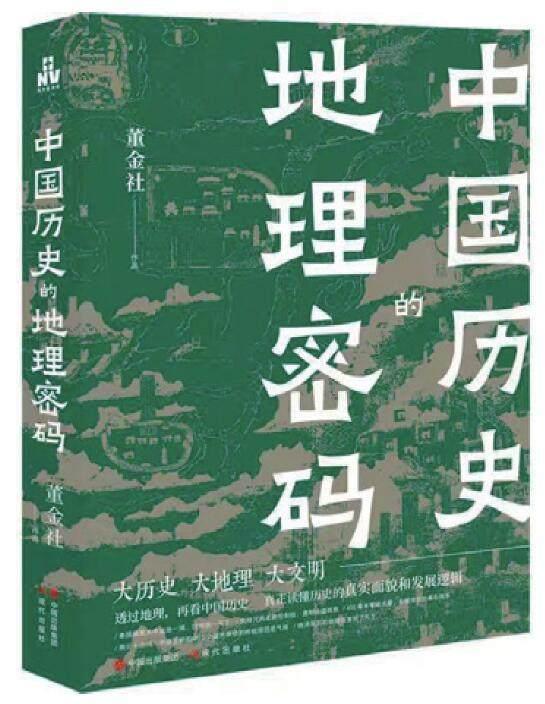

The Evolution of Geographical Units over Two Thousand Years: Vicissitudes of the Sea and Mulberry Fields

The author of this book fully absorbs the research achievements of predecessors, using information about natural geographical elements such as climate change, natural disasters, and environmental transitions compiled from documents like the Tribute of Yu, the Records of the Grand Historian, and the Book of Han. By referring to the findings of modern geographical science and analyzing the relationship between the geographical environment and historical evolution over a long period, the book uncovers the hidden laws of history and geography, offering both a vast sense of geographical space and a profound historical depth.

The Geographical Code of Chinese History

Dong Jinshe

Modern Press

September 2023

88.00 (CNY)

Dong Jinshe

Dong Jinshe is a senior economist and formerly taught at Shandong Normal University.

1. Cyclical Expansion and Contraction of Desertification in the North and Its Consequences

The desertification in the northern regions has undergone multiple expansions and contractions. Before the Qin and Han dynasties, eight major deserts, including the Taklamakan, Gurbantünggüt, and Badain Jaran deserts, along with four major sandy areas such as the Maowusu, Hunshandake, Hulunbuir, and Horqin sandy lands, had already formed and experienced several cycles of expansion and contraction under the influence of climate change.

After the Qin and Han dynasties, the process of desertification showed a fluctuating expansion trend, with clear regional differences: to the west of Helan Mountain, desertification significantly intensified during warm periods, while desert areas shrank during cold periods. To the east of Helan Mountain, green cover rates increase during warm periods, whereas during cold periods, deserts expand, and green areas diminish. This is likely related to the increased activity of the summer monsoon, where the rain belt moves northward into the inland during warm periods, increasing precipitation and thus enriching forests and grasslands, leading to an increase in vegetation cover. However, the process of desertification in some areas does not correspond entirely with climate change. For example, the activation of sand dunes in the Kubuqi Desert during the warm periods of the Han and Sui-Tang dynasties was related to increased human activity (such as population growth, land reclamation, and livestock grazing on vegetation). In summary, during the Sui, Tang, Song, and Yuan dynasties, desertified areas in the eastern sandy regions contracted, and vegetation in all four sandy lands showed signs of recovery, overall reducing the area of shifting sands. During the Ming and Qing dynasties, the area of desertified land in the eastern regions expanded, with the Maowusu Sandy Land, the Horqin Sandy Land, and the Hunsandak Sandy Land all undergoing desertification and vegetation degradation.

The relationship between climate change and desertification helps us understand the mechanisms behind the conflicts between nomadic and agricultural societies. In warm periods, when deserts weaken and vegetation increases, nomadic tribes can live comfortably off grazing, while agricultural societies can also farm and graze in the border areas between farming and grazing lands, leading to peaceful coexistence. However, during cold periods, with the degradation of grasslands east of Helan Mountain and the expansion of deserts, nomads are forced to migrate southward in search of pastures and food, and agricultural societies are unable to cultivate or defend the borders. This leads to the neglect of border defenses, enabling pastoralists to invade from the north, thereby igniting wars and contributing to the general decline of northern societies. Some scholars believe that the geographical environment changes slowly and has little impact on history, trying to downplay the main role of geographical environmental changes. This is because they do not realize the “butterfly effect” of group responses — when people from the same tribe or village are killed, and the survival of the group is threatened, it can lead to intense resistance from the entire tribe, leading to significant historical events. In understanding history, the amplifying effect of human societies on natural changes should be fully recognized.

2. Changes in the Loess Plateaus Geographical Environment and Their Impact

The Loess Plateau, unique to China, is formed by the accumulation of loess on bedrock surfaces, with its range divided into broad and narrow definitions. Broadly defined, the Loess Plateau, or the loess region, spans an area of 635,000 square kilometers, comprising 381,000 square kilometers of primary loess and 254,000 square kilometers of secondary loess (with primary loess formed by weathering and in-situ accumulation, and secondary loess transported and deposited by wind and water), mainly consisting of the Shanxi Plateau, Shaanxi-Gansu-Ningxia Plateau, Longzhong Plateau, Ordos Plateau, and Hetao Plain; Narrowly defined, the Loess Plateau roughly extends from the Great Wall in the north to the Qinling Mountains in the south, from Wushaoling in the west to the Taihang Mountains in the east, including most of Shanxi, north-central Shaanxi, central-eastern Gansu, southern Ningxia, and eastern Qinghai, covering about 300,000 square kilometers.

Loess, composed of fine sand particles, is hard when dry but becomes soft and sticky upon wetting, making it prone to erosion by rain, resulting in unique landforms such as plateaus, ridges, and mounds, with extensive ravines and rugged, fragmented terrain. When vegetation is significantly cut down and the ground is exposed, the loess is easily eroded. With the arrival of rain, water carrying silt flows down, raising the riverbed of the lower Yellow River and causing breaches and floods.

Over the past 2,000 years, the Loess Plateau has trended towards fragmentation due to prolonged erosion, with areas such as Suide and Wubao in Shaanxi and Liulin and Linxian in Shanxi experiencing valley densities greater than 10 kilometers per square kilometer. This is equivalent to a total length of ravines exceeding 10 kilometers per square kilometer, resembling the wrinkles on an old farmers forehead, densely packed and intersecting. Areas around Yanan, Zhidan, and Yanchang have valley densities of 7.0 to 10.0 kilometers per square kilometer. The loess plateau region east of the Liupan Mountains is second, with the lines along Xifeng, Tongchuan, Huangling, and Yichuan ranging from five to seven kilometers per square kilometer; The loess plateau region west of the Liupan Mountains and the rocky mountain areas and river valleys to the east of the Lvliang Mountains, Huanglong Mountain, and Ziwuling have lower densities but still range from 1.7 to 6.4 kilometers per square kilometer. The higher the ravine density, the more severely the land is fragmented, leading to transportation challenges, smaller land parcels, adverse conditions for cultivation, and a decrease in the lands carrying capacity.

Loess transported by the Yellow River to its middle and lower reaches has leveled or raised the elevation of the North China Plain and the Huang-Huai Plain, expanding the coastal land area. Without the Yellow River, there would be no North China Plain downstream. The Yellow River connects the east and west of China.