“Dialogues with Youngsters” Series

This series selects 20 heroic figures from recent and modern history known for their bravery and steadfastness, as well as 20 scientists from the technological field who have made significant contributions in recent and modern times. It introduces these heroes to children and teenagers through stories told in refined and impactful language. They are the backbone of China, the pride of the nation, and the most lovable and respectable individuals.

“Dialogues with Youngsters” Series

Yang Jian

Modern Education Press

February 2023

29.80 (CNY)

Yang Jian

Yang Jian is the former deputy editor of Sohu News. Long engaged in the media industry, he is dedicated to promoting traditional Chinese culture and is enthusiastic about public welfare.

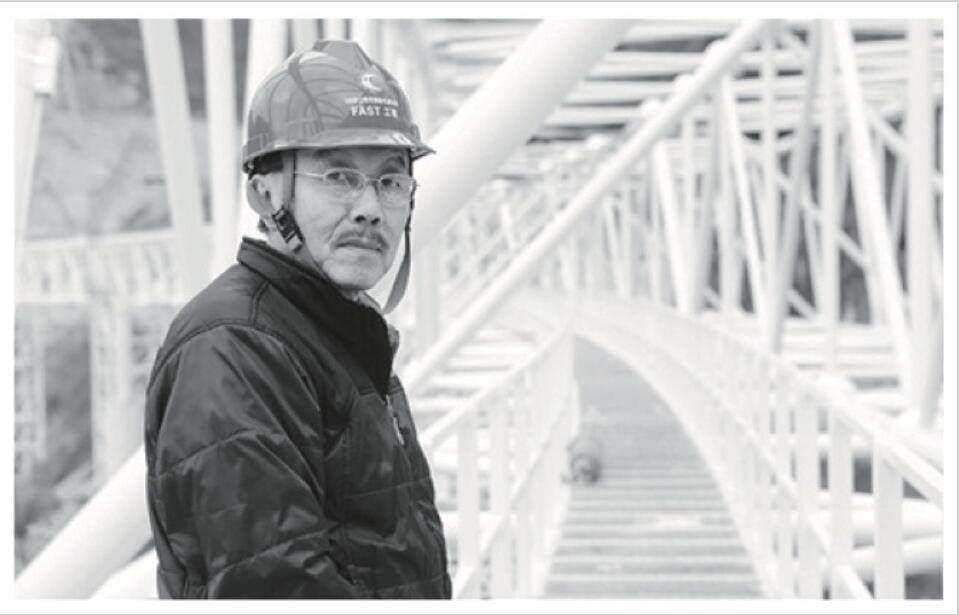

Nan Rendong:

A Lifetime for One Cause

Nan Rendong (February 19, 1945 – September 15, 2017), an astronomer, hailed as the “Father of Chinas Sky Eye,” served as the chief scientist and chief engineer of the “Chinese Sky Eye” project (FAST, the Five-hundred-meter Aperture Spherical Radio Telescope). From the projects preliminary research in 1994 to its completion in 2016, Nan Rendong persisted for 23 years. Over these 23 years, he went from his prime to his twilight years, transforming a simple idea into a national treasure, achieving a project unique in the world for China. On the evening of September 15, 2017, Nan Rendong passed away at age 72. Later, he was posthumously awarded the titles “Peoples Scientist” and “Role Models of Dedication.”

On September 15, 2017, this respected elder passed away. Many people lamented upon hearing the news: “Sorry to have only known you in such a manner!” He was Nan Rendong, who became widely recognized as the “Father of Chinas Sky Eye” only after his death.

Before constructing the “Chinese Sky Eye,” Grandpa Nan had already been renowned both domestically and internationally. In the 1980s, while many sought ways to go abroad, Nan Rendong, who was lecturing and visiting overseas, made a decision quite different from others: “I want to return to my country.”

He declined heavy recruitment offers and returned. The income from a year of hard work at home was only equivalent to a days income abroad, but he had no regrets.

In 1993, at the conference of the International Union of Radio Science, it was proposed to build a new generation of large radio telescopes. Attracted by the dream of exploring the universe, Nan Rendong excitedly said to his colleagues, “Lets build one, too!”

He was 48 years old when he made this statement. By the time he realized this dream, he was already 71.

At that time, everyone thought he was joking, except for him, who took it seriously.

From then on, he transformed from a scientist into a “salesman.” At conferences large and small, both at home and abroad, he promoted his project to everyone he met. The not-so-eloquent man once joked about himself: “Ive been flattering the whole world, seeking its support for our project.”

This perseverance lasted for 12 years.

Meanwhile, for site selection, he traveled through remote mountains with over 300 satellite remote sensing images, braving wind and rain.

In 2006, the “Sky Eye” project was officially approved, and Nan Rendong became the chief engineer. This chief engineer was unique: dressed like a construction worker, with a stubbly beard, yet knowledgeable in astronomy, design, mechanics, materials, and machinery, overseeing everything.

Over ten years, the “Sky Eye” evolved daily until its completion. So did Nan Rendong, aging day by day.

In 2016, as the “Sky Eye” was nearing completion, Nan Rendong collapsed from exhaustion. In his last interview, his voice was hoarse, speaking slowly without complaints or dreams, only mentioning his fear of owing others and the country, saying he was merely fulfilling a bit of his duty.

In 2017, around the time the “Sky Eye” was to celebrate its first anniversary, Nan Rendong passed away.

Many people find it hard to look directly at Grandpa Nans retrospective photo, for his gaze could penetrate the soul and purify the heart, making tears and blood boil in an instant.

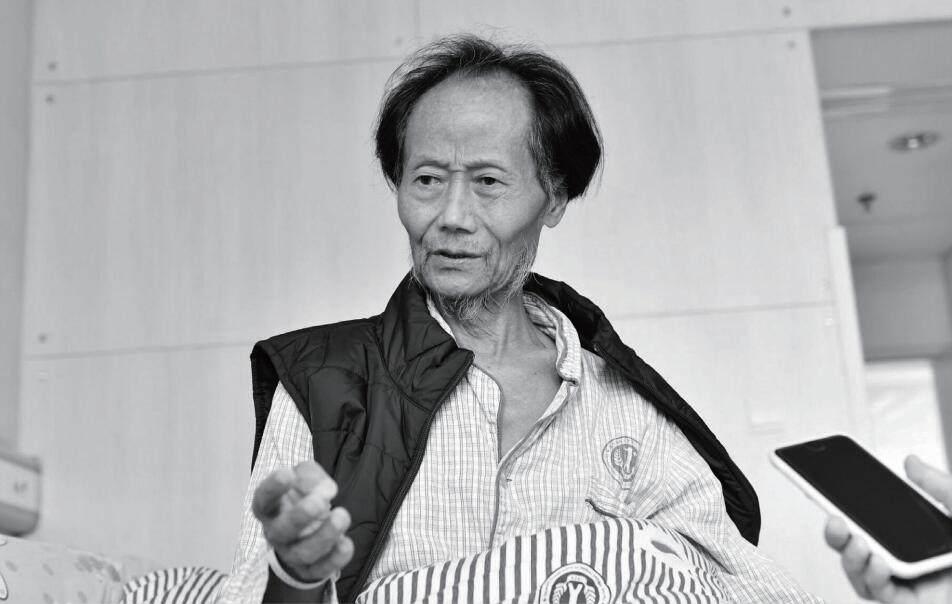

He Jiaqing:

The “Beggar” Professor

He Jiaqing (1949 -- 2019) was a professor at the College of Life Sciences, Anhui University. He was known as Chinas “Konjac King,” and the delicious Konjac we eat today owes much to him. He Jiaqing had extraordinary perseverance and a profound love for the land beneath his feet and the people who toil on it. He was indifferent to fame and fortune, living a life of simplicity, with his daily meals throughout the year consisting mainly of steamed buns and porridge. In his final moments, He Jiaqing donated his corneas. The surgeon remarked, “Professor Hes corneas were exceptionally clear.”

There might not be a more “silly-looking” professor in this world than He Jiaqing. With a gaunt face, messy hair like a birds nest, loose-fitting glasses, and a worn-out Zhongshan suit he had worn for 28 years, this is hardly the appearance expected of a university professor!

His name is He Jiaqing, and he was a professor who lived like a wandering monk with legs that never tired.

At 35, he left home for 225 days, trekking 12,684 kilometers to comprehensively explore the Dabie Mountains for the first time in history, self-funded, collecting 3,117 different plant specimens and nearly ten thousand plants in total.

Later, as a deputy county chief, he walked 800 kilometers over six months, visiting 23 townships and collecting 1,536 plant specimens.

At 49, he left a “will,” spending 305 days at his own expense aiding poverty relief in the Southwest, covering over 30,000 kilometers (400 of which were on foot). When he left, his weight was 60 kilograms. Upon his return, it had dropped to only 40 kilograms.

On each solo trek, he faced deathly odds, enduring trials as numerous as the legendary “nine by nine,” i.e., eighty-one hardships.

When he ran out of money, he resorted to begging for two months. During unbearable hunger, he spent nights in pigsties, feeding on pig slop. In the mountains, he was once nearly killed by a venomous snake bite. During his toughest moment, he called home: “I might not make it this time, and I just want to hear my daughters voice.”

Fear and exhaustion constantly tormented the frail He Jiaqing, yet after panicking and fearing, he would rest a bit and hit the road again.

Many couldnt understand: What could be worth such sacrifice? Was he foolish?

He once answered: “Though of humble status, I cannot forget my concerns for the nation. All these hardships are self-sought. If this makes me silly-looking, I am willingly so.”

He Jiaqings entire life was a battle against poverty, the first half for himself, the latter for the welfare of others.

He grew up in extreme poverty; his mother died early, and his father supported eight people by doing hard labor. If not for the charity of teachers and classmates, he wouldnt have even afforded elementary school.

He Jiaqing treasured an accounting book left by his father. It meticulously recorded which year his tuition was waived, which teacher gave him a pair of old rubber shoes, and which classmates mother gave him a set of old clothes. Thus, from his childhood, he vowed: “For every handful of soil given to me, I will return a mountain.”

At the end of his “journey to the West,” there were the impoverished people of the mountainous areas. Thus, even past his sixties, he walked with the vigor that young people couldnt match.

He was known as Chinas “Konjac King,” making many wealthy and prosperous. Fame and fortune were once within his reach, yet he spent his life in poverty, facing peril, without taking a dime.

In July 2019, the septuagenarian He Jiaqing was found to have collapsed on the road to poverty alleviation. Only after examination was it discovered he was in the late stages of a terminal illness beyond medical help. Doctors said his body was “completely worn out,” and it was a miracle he had lasted this long.

Three months later, Old He passed away. He no longer needed to walk briskly, and he could finally rest.

He had already prepared his eulogy: “I am gone, yet I live on. No need for ceremonies, no need for tears down the cheeks, no need for eulogies, please forget me. Mud or snow, everything returns to the earth, and I will grow from this earth.”