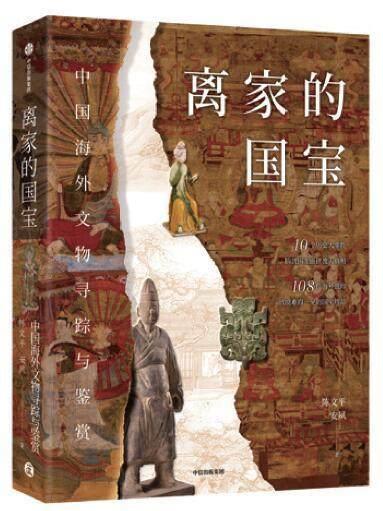

The Catastrophe of Civilization: The Destruction of the Grandeur of the Old Summer Palace

The first part of this book follows the thread of ten major events involving the dispersal of cultural relics, unveiling the complex truths behind the loss of national treasures. The latter part meticulously selects 108 precious relics overseas, ranging from the Neolithic era to the Qing Dynasty, covering Dunhuang relics, calligraphy, ceramics, bronzes, jades, lacquerware, sculptures, and oracle bone scriptures, etc. It interprets the historical background, craftsmanship, color details, aesthetic design, and symbolic meanings, encompassing exquisite collections from dozens of institutions abroad, offering a glimpse into the rare treasures of Chinese heritage.

The National Treasures Away from Home

Chen Wenping, An Su

CITIC Press Group

November 2023

138.00 (CNY)

Chen Wenping

Chen Wenping is a professor at Shanghai University, deputy director of the China Overseas Cultural Relics Research Center, and a member of the expert review committee for the China National Arts Fund (CNAF). Chen Wenpig has held positions at Shanghai Museum and Shanghai University. His main research areas include cultural relics lost overseas, the history of ceramics, and art appreciation.

An Su

An Su graduated from the Tianjin Academy of Fine Arts and the Department of Art History at the Chinese National Academy of Arts. Currently, she serves as a curator and exhibition organizer in the Collection Department of the Tsinghua University Art Museum. She is also the secretary of the sub-project group for the “Research on the Standard System of Chinas Intangible Cultural Heritage” under the National Social Science Fund project, and she mainly engages in the preservation of cultural relics and research in art history and museology.

October 18, 1860 (the fifth day of the nineth month of the Xianfeng decade of the Qing Dynasty).

Suddenly, dense smoke billowed into the sky northwest of Beijing, with flames reaching the heavens, turning half the sky blood-red as the fire blazed unabated for three days. The Old Summer Palace, acclaimed as the “Garden of all Gardens” and “Peerless Garden,” an architectural marvel without parallel, was set ablaze by the Anglo-French Allied Forces, with countless treasures and artifacts plundered. The looting of the Old Summer Palace was not only a significant loss to Chinas cultural heritage but also a major loss to the worlds cultural heritage.

The Old Summer Palace is located in Haidian district, the northwest suburbs of Beijing (formerly within the Hai Dian jurisdiction), and together with the adjacent Changchun and Wanchun (originally named Qichun) Gardens, it was known as the “Three Gardens of the Old Summer Palace.” The three gardens were adjacent to each other, interconnected by a system of waterways. It was a magnificent royal garden, created and managed over more than 150 years by five reigns of emperors during the Qing Dynasty.

Not only was it renowned for its picturesque landscapes, earning it fame as a garden, but it was also a royal museum housing an extensive collection, truly a treasure trove of culture. As a place for Qing emperors to conduct affairs of state and rest, it housed a vast collection of cultural relics, treasures, paintings, and a large number of important archival documents from various dynasties. Nearly every hall contained many valuable artifacts and exquisite items, including top-grade rosewood carved furniture, delicate ancient porcelain, priceless paintings by famous artists from various dynasties, pure gold objects, and decorative pieces and artworks made from precious materials such as pearls, gemstones, jade, and ivory, in an endless and comprehensive array. In Shewei City, where Buddha statues were worshipped, the collection, accumulated since the Kangxi period, astonishingly numbered over 100,000 statues made of pure gold, silver-plated, jade-carved, and bronze-cast. The sheer volume and the luxurious and exquisite nature of the rare treasures and historical artifacts within the Old Summer Palace were beyond imagination.

On October 6, 1860, the invading British and French Allied Forces stormed into this long-famed palace of art. The day after entering the Old Summer Palace, the British and French forces immediately “appointed three commissioners each from England and France to jointly decide on the distribution of the gardens treasures.” The French commander Montauban informed the French Foreign Minister on the same day: “I have ordered the French commissioners to prioritize items of the greatest value in terms of art and archaeology. I will present to His Majesty the Emperor, through your excellency, items of extreme rarity in France, to be stored in the French Museum.” The British commander Grant also immediately “ordered officers to collect items that should belong to the British.”

This world-renowned garden was left in ruins three days later, with almost all of its cultural treasures and artifacts gone. The gigantic architectural complex, a blend of Chinese and Western styles, meticulously created and maintained over 150 years by five generations of emperors, at the cost of countless resources, was destroyed overnight. The burning and looting of the Old Summer Palace represent an immeasurable loss in the history of human culture. The invaders not only destroyed this unparalleled masterpiece of a garden but also plundered and damaged historical artifacts treasured over the dynasties in China. These rare art treasures, either burned, wantonly destroyed, or looted overseas, were invaluable. Wenyuan Pavilion, which housed the classic masterpieces of Chinas excellent cultural heritage, such as the Complete Library in the Four Branches of Literature and the Collection of Ancient and Morden Books, was also burned down. Admonitions of the Instructress to the Court Ladies (a Tang Dynasty copy) by Gu Kaizhi, a great painter of the Eastern Jin Dynasty, was looted by the British and is now housed in the British Museum in London. The Forty Scenes of the Old Summer Palace, painted by Shen Yuan and Tang Dai, was looted by the French and is now in the National Library of France in Paris.

In 1900 (the 26th year of Emperor Guangxu of the Qing Dynasty), during the invasion of Beijing by the Eight-nation Alliance, the Old Summer Palace faced another calamity. Many newly added ancient bronzes, precious porcelain, coral screens, ivory carvings, gold and silver utensils, fine silk and satin, and rare treasures, as well as surviving and gradually restored buildings within the garden, were all plundered and destroyed, revisiting the devastation that occurred 40 years earlier, leading to the destruction of the Old Summer Palace.

The Remnants of Grand Waterworks of the Old Summer Palace

The loss of cultural and national treasures from the Old Summer Palace is difficult to quantify accurately. The number of cultural and artistic treasures that have been lost to Europe and America is astonishing. Besides the United Kingdom, France is one of the most important centers of collection.

Zhang Deyi, who served in the Qing court during the Tongzhi and Guangxu reigns, recorded in his book Nautical Myth what he witnessed in London, “I came to a place, vast and clean, where everything arranged up and down was from the lost treasures of Chinas Old Summer Palace, placed here for lease or sale.” This included the emperors dragon robe, the empress dowagers court beads, as well as curios and scrolls.

In August 1904 and August 1905, Kang Youwei visited France twice and wrote Travel Notes in France, documenting the large number of Old Summer Palace relics he saw in French museums. In one museum, I encountered an ancient artifact from the Old Summer Palace, a white jade seal known as “Qianlongs Imperial Seal.” It features intricately carved designs of two dragons playing with a pearl at the top. The quality of the jade is exceptional, making it a supremely divine object. Kang Youwei lamented, “In the past, I saw countless imperial writings sealed with this stamp in Beijing, yet I never saw it. And now, unexpectedly, Im touching it.” He couldnt help feeling deeply sorrowful, saying, “Seeing the treasures of the Old Summer Palace is heartbreaking.”

About 65 kilometers southeast of Paris, France, on the left bank of the Seine River, approximately three kilometers away in the famous Fontainebleau forest, lies one of the largest royal palaces built by French kings -- Ch?teau de Fontainebleau. In 1863, three years after the end of the Second Opium War, Napoleon III and Empress Eugénie built a Chinese pavilion here, housing thousands of precious artifacts looted from the Old Summer Palace, all presented by Montauban in 1860. These selected treasures are from the Old Summer Palaces looted artifacts, and each piece can be considered a rare treasure.

To obtain firsthand information, I visited the Old Summer Palace twice, and in July 2014, I also went to the Chinese Pavilion at the Ch?teau de Fontainebleau for specialized research.

At the entrance of the Chinese Pavilion stands a “Treasure Dragon Pavilion,” exquisitely carved and brightly colored, a rare imperial artifact.

Ch?teau de Fontainebleau, France

The “Treasure Dragon Pavilion” display of at the entrance of the Chinese Pavilion of Ch?teau de Fontainebleau

Entering the grand doors of the Chinese Pavilion, one is immediately greeted with rare treasures from China, looking up to see three huge kesi (silk tapestry) Buddha portraits from the Qianlong period decorating the entire ceiling space, giving the Chinese Pavilion an extremely luxurious appearance. It is said that “an inch of kesi is worth an inch of gold.” Kesi products have always been imperial items, and they are known for their exquisite craftsmanship, smooth lines, clear layering, and a strong sense of three-dimensionality. These three silk tapestry pieces feature the triad of past, present, and future Buddhas along with their eighteen disciples, the Eighteen Arhats, and the images of the Four Great Guardian Warriors, presenting a dignified and solemn appearance. They are rare treasures among silk tapestry Buddha portraits, likely originating from a Buddhist hall or a Tibetan Buddhist temple within the Old Summer Palace.

Full View of the Exhibition Hall in the Chinese Pavilion of Ch?teau de Fontainebleau

In the center of the exhibition hall, beneath the three Kesi Buddha portraits, hangs a magnificent cloisonné enamel chandelier. The chandelier is assembled in two parts: the top part is a Ming Dynasty cloisonné vase, and the bottom part is a lid from a large square box made during the Qianlong period, uniquely shaped and providing aesthetic pleasure. Below the chandelier is placed a cloisonné enamel beast-knobbed gilded four-legged large square box, originally a pair, one of which had its lid repurposed as the lower part of the chandelier and fitted with a finely made Western-style knob. It has been verified that this square box was used as an ancient “ice box” to store ice blocks and fruits. At the entrance of the exhibition hall, a pair of large cloisonné incense burners of different designs are placed. The ice box and incense burners were likely daily utensils in the Hall of Supreme Harmony or the Jiuzhou Qingyan Hall of the Old Summer Palace. Cloisonné, also known as copper-wire enamel, was introduced to China from Europe via the Silk Road. It was named after the Jingtai Emperor of the Ming Dynasty, who brought this craft to its first peak. The production process of cloisonné is extremely complex, resulting in a crystalline and exquisite appearance with vivid and eye-catching patterns, making it known as the essence of national treasures.