Impacts of information about COVID-19 on pig farmers’ production willingness and behavior: Evidence from China

Huan Chen ,Lei Mao ,Yuehua Zhang,

1 School of Public Affairs,Zhejiang University,Hangzhou 310058,China

2 School of Insurance,Central University of Finance and Economics,Beijing 100081,China

3 Innovation Center of Yangtze River Delta,Zhejiang University,Jiaxing 314100,China

Abstract This paper examines the impacts of information about COVID-19 on pig farmers’ production willingness by using endorsement experiments and follow-up surveys conducted in 2020 and 2021 in China.Our results show that,first,farmers were less willing to scale up production when they received information about COVID-19.The information in 2020 that the second wave of COVID-19 might occur without a vaccine reduced farmers’ willingness to scale up by 13.4%,while the information in 2021 that COVID-19 might continue to spread despite the introduction of vaccine reduced farmers’ willingness by 4.4%.Second,farmers whose production was affected by COVID-19 were considerably less willing to scale up,given the access to COVID-19 information.Third,farmers’ production willingness can predict their actual production behavior.

Keywords: COVID-19,randomized experiment,information treatment,production willingness

1.Introduction

Pig production plays an important role in China.On the one hand,China is a global leader in pig production,with more than 671.28 million slaughtered hogs and 449.22 million pigs in stock (NBSC 2022).On the other hand,pork is the most popular meat in China,and about half of pork worldwide is consumed by Chinese.Fluctuations in pig production not only affect pig farmers and the pig farming industry but also influence the consumer price index (CPI) in China (Maet al.2021).

However,pig production in China has experienced substantial fluctuations in recent decades,which is known as the pig cycle (Nieet al.2009;Zhao and Wu 2015).Previous studies have utilized the cobweb theorem to show that farmers’ production adjustments and biological lags in supply response are the main causes of large fluctuations in pig production (Coase and Fowler 1935;Ezekiel 1938;Harlow 1960).In China,pig farmers tend to expand production when pork prices are high,however,it takes more than a year to produce pork to enter the market.Conversely,low pork prices prompt farmers to slaughter sows and reduce production,thereby limiting the future pork supply (Galeet al.2012;Chavas and Pan 2020).Extensive research has shown that limited information access is a significant obstacle to technology adoption and improved production practices among farmers (Goyal 2010;Aker 2011;Shiferawet al.2015;Maet al.2017).Farmers’ pig-raising decisions are based on subjective expectations about future market conditions and may be overly optimistic or pessimistic (Chavas 1999).Therefore,the imperfect information available to pig farmers regarding pig production is a key factor contributing to the pig cycle.The question is whether we can optimize pig farmers’ willingness and decision-making regarding pig raising.

COVID-19 has been found to pose impacts on hog production in various aspects,including supply chain (Wanget al.2020),processing capacity (Hayeset al.2021),labor supply (McEwanet al.2021),meat prices (Yuet al.2020;Lusket al.2021;Ramseyet al.2021),and global trade (McEwanet al.2020).Pig production in China is more vulnerable to COVID-19 than other agricultural production sectors for two reasons.First,COVID-19 and related restrictions,especially transportation restrictions,significantly impacted feed supply,drug supply,and hog sales.Unlike crops that depend on land nutrients for growth,pigs need adequate feed and timely medication to grow healthy.However,transportation restrictions resulted in feed and drug shortages in pig farms (Zhuoet al.2020).In addition,traffic restrictions and declines in pork consumption made it difficult to sell pigs (Yuet al.2020).Second,China’s pig production has been experiencing the outbreak of African swine fever (ASF) since 2018.Hog inventory at the end of 2019 was at the lowest historical level in China because of ASF.The recovery of pig production faces more uncertainty with the COVID-19 outbreak (Wanget al.2020).However,pig farmers in China may overlook the impacts of COVID-19 on pig production.

This study tries to optimize pig farmers’ production willingness and behavior by providing information about COVID-19 during the pandemic through randomized experiments in China.We introduce different information regarding COVID-19 according to the varied prevailing phases of COVID-19 in 2020 and 2021,respectively.In randomized experiments,respondents were first randomly divided into two treatments.Respondents in the baseline treatment were asked to answer a specific question about whether they were willing to scale up pig production,while for respondents in the treatment with information regarding COVID-19 (hereafter called “the information treatment”) the same question was asked but with an endorsement.Specifically,the endorsement information in 2020 is “the second wave of COVID-19 might occur in the absence of a vaccine”,while the information in 2021 is “COVID-19 might continue to spread despite the introduction of vaccine”.The endorsements are different between two years and reflect corresponding prevailing phases of COVID-19.The difference in responses between the information treatment and the baseline treatment,therefore,can be interpreted as the effect of endorsement (Lyallet al.2015).

Our paper contributes to current literature in the following four fields.First,to the best of our knowledge,this study is the first to examine the causal effects of information about COVID-19 on farmers’ production willingness by randomized experiments.Information experiments have been widely used to study the effects of information on human behavior,including environmental protection (Ferraro and Miranda 2013),political participation (Margettset al.2011),and consumption (Wichman 2017).Research on farmers’ production behavior has mainly focused on the effects of mobile phone information on crop type,area,price,and technology adoption (Goyal 2010;Aker 2011;Fafchamps and Minten 2012;Aker and Ksoll 2016).This study enriches the literature on information intervention experiments by applying them to study pig farmers’ production willingness.Second,this study provides insights into understanding the impacts of real COVID-19 on pig production from the information perspective.Our findings show that pig farmers were less willing to scale production when they received information about COVID-19.In addition,previous research has focused on the impacts of COVID-19 at an early stage,while much less is known about its impacts at a later stage.We evaluate the impacts of information according to different prevailing stages of COVID-19 by using data from two years.Third,we provide evidence that pig farmers’ willingness to scale up production could predict their actual pig-raising behavior.Previous studies found that willingness could lead to actual behavior (Armitage and Conner 2001;Sheeran 2002),while a recent study showed a willingness-behavior gap among pig farmers in bioenergy production (Heet al.2022).We demonstrate the consistency of farmers’ willingness to expand production using the follow-up survey data.Finally,we contribute to whether farmers with/without actual COVID-19 experience respond differently to information regarding COVID-19.Indeed,current research shows that experience influences decision-making (Cohenet al.2008;Caiet al.2021).We find that farmers whose actual production had been severely affected by COVID-19 were less willing to scale up when exposed to information regarding COVID-19.

The remainder of this paper is structured as follows.Section 2 provides background information on pig production and the study area.Section 3 describes data,experimental design,variables,and empirical strategy.Section 4 presents experimental results.Section 5 discusses the results.Finally,Section 6 concludes the paper.

2.Background

2.1.Pig production

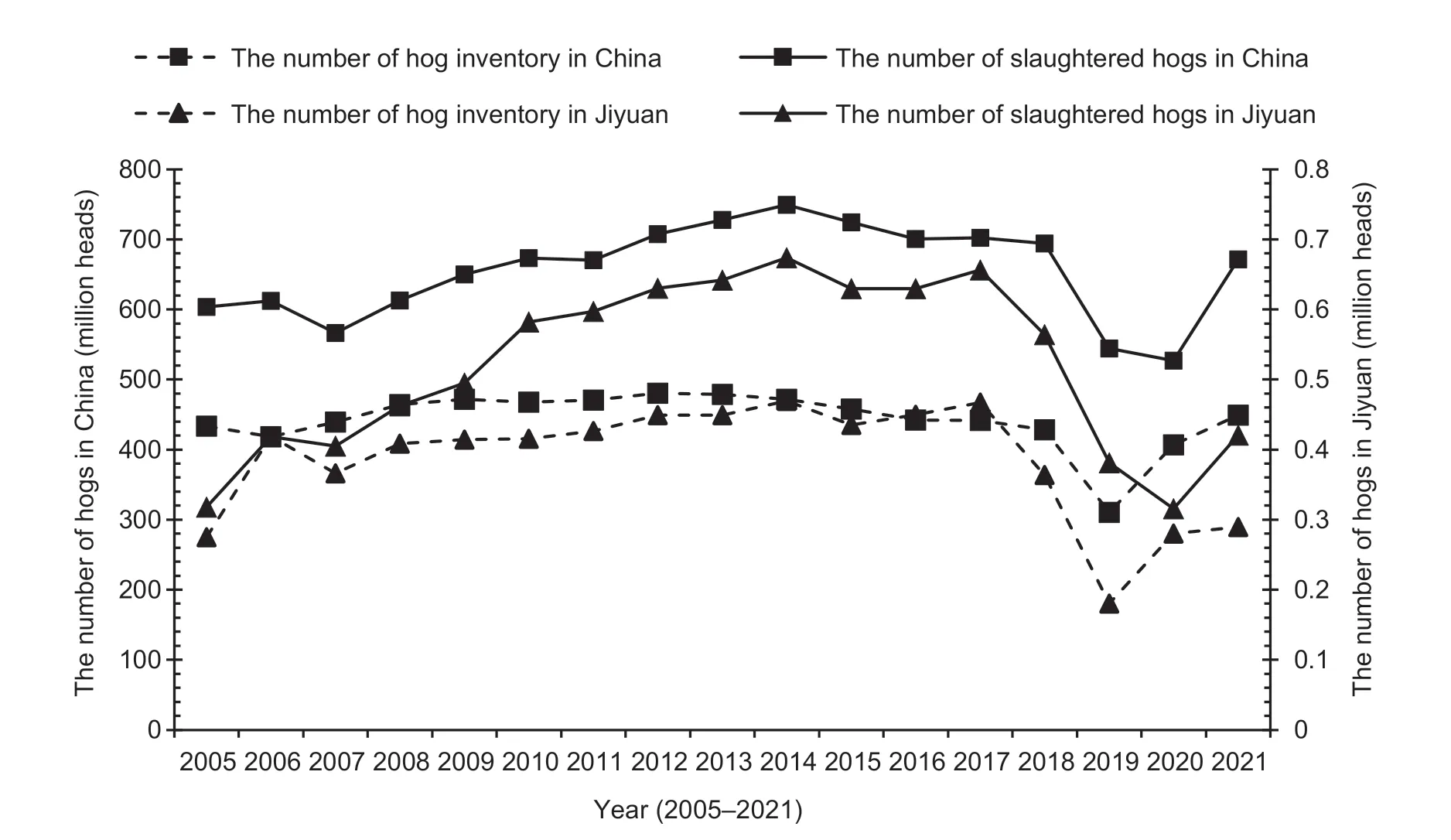

China ranks as the top pork producer and consumer in the world.In 2020,mainland China produced 41.13 million tons of pork,accounting for 38% of global pork production (FAO 2023).China’s pork production,however,has fluctuated dramatically in recent years because of ASF.ASF is a highly contagious and deadly viral disease in pigs,which could incur big losses to farmers and significantly affect pig production (Costardet al.2009;Blomeet al.2020;Youet al.2021).It was first detected in Liaoning Province in August 2018 and then spread to all provinces in China.From 2018 to 2019,162 cases of ASF were reported in China in total,and 1.2 million pigs were culled.As a result,China’s hog inventory at the end of 2019 fell to the lowest level of 310.41 million heads.To recover the hog inventory,the Chinese government made huge efforts like loosening restrictions on the establishment of new pig farms,encouraging industrialization of pig production,and providing financial support.These measures played a positive role in recovering China’s pig production.As shown in Fig.1,hog inventory rebounded to 449.22 million in China at the end of 2021,which exceeds the number of hog inventory prior to the outbreak of ASF.

Fig.1 Pig production in China and Jiyuan County of China (2005-2021).The number of hog inventory was calculated according to the data at the end of each year.Source: China Statistical Yearbook and Henan Statistical Yearbook.

Fig.2 shows the monthly wholesale pork prices in China from 2018 to 2021.In 2018,the average pork price was 18.71 CNY kg-1,with small fluctuations.However,because of the sharp decline in pork supply,prices began to rise in 2019 and peaked in 2020,with an average price of 44.98 CNY kg-1.As the hog inventory recovered from the impact of ASF,pork prices plummeted in 2021.In particular,the price was only 19.56 CNY kg-1in October 2021.Low prices caused economic pressure on pig farmers and significantly affected farmers’ production behavior.Data from the Ministry of Agriculture and Rural Affairs of China (MARA) shows that since May 2021,the cost of raising a pig has exceeded its market value,and farmers began to lose money.

Fig.2 Monthly pork prices in China and Henan Province of China (2018-2021).Source: Agricultural Product Market Information Platform,Ministry of Agriculture and Rural Affairs of China,http://ncpscxx.moa.gov.cn/product-web.

2.2.Study area

This study was conducted in Jiyuan County in Henan Province,located in central China,which has a population of 0.727 million and covers 745.56 m2.In Jiyuan County,pig production is an important source of income for farmers and tax revenue for the government,with an average production of over half a million pigs per year (Rao and Zhang 2020).In 2015,the number of slaughtered hogs in Jiyuan was 629,700.As shown in Fig.1,the trends of hog inventory and slaughtered hogs in Jiyuan between 2005 and 2021 resemble similar patterns in China.The number of slaughtered hogs fell from 656,300 in 2018 to 315,700 in 2020 because of the pork price cycle and ASF.In early 2020,the Jiyuan government implemented policies to restore pig production.As a result,the hog inventory reached 280,000 at the end of 2020,increasing by 55.56% compared with 2019.The number of slaughtered hogs gradually recovered and increased to 420,800 in 2021.In addition,the trend of monthly wholesale pork prices in Henan Province is similar to that of China (Fig.2).

Only five COVID-19 cases were confirmed in Jiyuan in February of 2020.However,the lockdown measures were the same strict as in other areas.On January 25,the Jiyuan government initiated Class 1 Response to Public Health Emergency.Most public places were closed,and checkpoints were set up at all transportation hubs (e.g.,train stations and highway intersections),making it difficult to deliver passengers and goods.However,traffic started to recover from February 4,and other restrictions were gradually suspended.The outbreak of COVID-19 in Jiyuan was under control by the end of February 2020.

3.Data and methods

3.1.Data

Data used in this study are from two experiments and phone surveys conducted together in 2020 and 2021,respectively.The survey sample is from a baseline survey conducted in August 2017 and includes information from 1,343 pig farms in Jiyuan County.In July 2017,the Jiyuan Bureau of Agriculture and Rural Affairs of conducted a census of pig farms across the county and obtained the production information of all 4,614 pig farms.To conduct surveys,we first adopted a stratified random sampling approach based on the pig production scale and randomly selected 1,376 pig farm heads in 15 townships.We then collected baseline data in August 2017 and conducted follow-up surveys in February 2018,June and July 2020,and October 2021,respectively.In 2020 and 2021,we recruited senior undergraduate and graduate students as investigators to conduct phone surveys using phone numbers collected in the 2018 survey.The phone surveys included information on farmers’ demographics,production characteristics,and the impacts of COVID-19.Each questionnaire took about 15 min to complete.In 2021,farmers who completed the survey were paid a 20-CNY phone bill.Table 1 shows the sample sizes and response rates of phone surveys in 2020 and 2021.In the first phone survey,we reached 1,111 farmers,but only 784 farmers were still raising pigs.In the second phone survey,the number of farmers still raising pigs was 734,with a response rate of 74.09%.

Table 1 Survey dates,sample sizes,and response rates by survey waves

3.2.Endorsement experiments

Uncontrolled and unobservable variables might both affect farmers’ access to information regarding COVID-19 and their willingness to raise pigs.Therefore,we conducted endorsement experiments by exogenously assigning information regarding COVID-19 to identify the causal effect of information about COVID-19 on farmers’ pig production willingness.The experiment consists of two treatments: a baseline treatment and a treatment with information regarding COVID-19.

First,farmers were randomly assigned to either baseline treatment or information treatment.To achieve randomization,experimenters used dice rolls to determine the assignment of information regarding COVID-191At the beginning of each survey,the experimenter rolled a sixsided die.If the die landed on numbers 1 to 3,the farmer was assigned to the baseline treatment group.If the die landed on numbers 4 to 6,the farmer was assigned to the information treatment group..

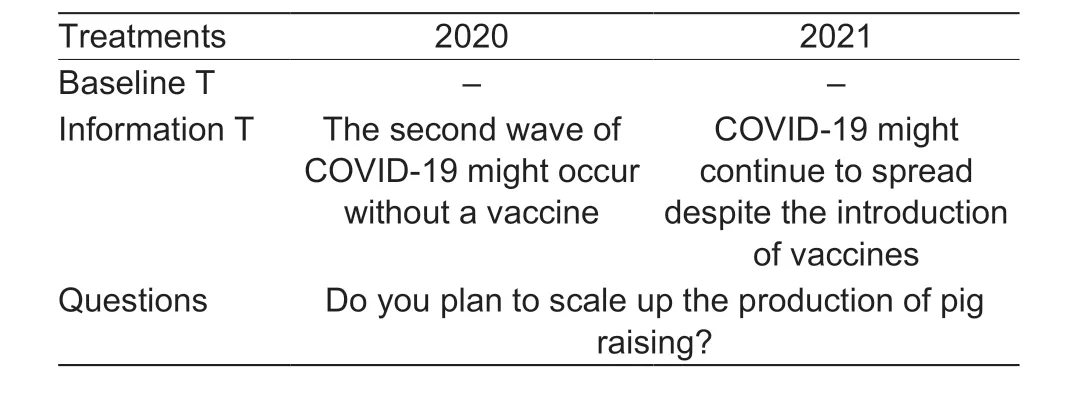

Next,farmers in the baseline treatment were asked about their willingness to scale up production.Farmers in the information treatment had to answer the same question after they were informed of information regarding COVID-19.The endorsements in the information treatment are different between 2020 and 2021 and are introduced according to the prevailing phases of the pandemic (Table 2).In 2020,the first wave of COVID-19 transmission in China was effectively contained by the end of the summer.However,COVID-19 quickly spread worldwide,leading the World Health Organization (WHO) to declare the COVID-19 outbreak a global pandemic in March.And in June and July 2020,there was no effective vaccine available for the general population.Thus,farmers in the information treatment in 2020 were told that “the second wave of COVID-19 might occur without a vaccine”.In 2021,vaccination rates continued to increase with the introduction of vaccines.By September 18,2021,1.022 billion people had received two doses of vaccine,accounting for 73% of the total population (https://app.www.gov.cn/govdata/gov/202109/19/476062/article.html).However,due to the continuous evolution of the virus,confirmed cases of COVID-19 occur intermittently in some areas.Thus,farmers in the information treatment of 2021 were informed that “COVID-19 might continue to spread despite the introduction of vaccines”.

Table 2 Randomized experiments in 2020 and 2021

Comparing the differences in responses between the two groups allows us to estimate the impacts of information regarding COVID-19 on farmers’ pig raising willingness.Farmers could be divided into four groups according to whether they received information regarding COVID-19 in 2020 and 2021 (Appendix A).The total number of observations is 1,126.Group I refers to farmers in the baseline treatment who never received any information about COVID-19 in these two years.Farmers in Group II and Group III received information in either 2020 or 2021,while farmers in Group IV received information both in 2020 and 2021.

3.3.Variables and descriptive statistics

Table 3 summarizes farmers’ responses to whether they are willing to scale up production by group and year.Generally,34.8% of farmers in 2020 indicated they were willing to scale up production,while the proportion of farmers’ willingness to expand production decreased sharply to only 10.7% in 2021,which reflects that factors affecting farmers’ willingness to raise pigs changed substantially across two years.

Table 3 The willingness to scale up pig production

In addition,Table 3 compares farmers’ response differentials between the baseline treatment and the information treatment in 2020 and 2021,respectively.Specifically,in 2020,40.9% of farmers in the baseline treatment indicated they were willing to scale up,while this proportion declined to 28.5% for farmers in the information treatment.In 2021,in spite of farmers coming from information treatment or baseline treatment,their willingness to expand production dropped to 8.5 and 12.7%,respectively.Compared with farmers in the baseline treatment,their counterparts in the information treatment were significantly less willing to expandproduction.Farmers in the information treatment were 12.4% less willing to expand production in 2020 and were 4.2% less willing to expand in 2021.Differences are significant in both years and provide evidence that access to information about COVID-19 reduced farmers’ willingness to scale up production.

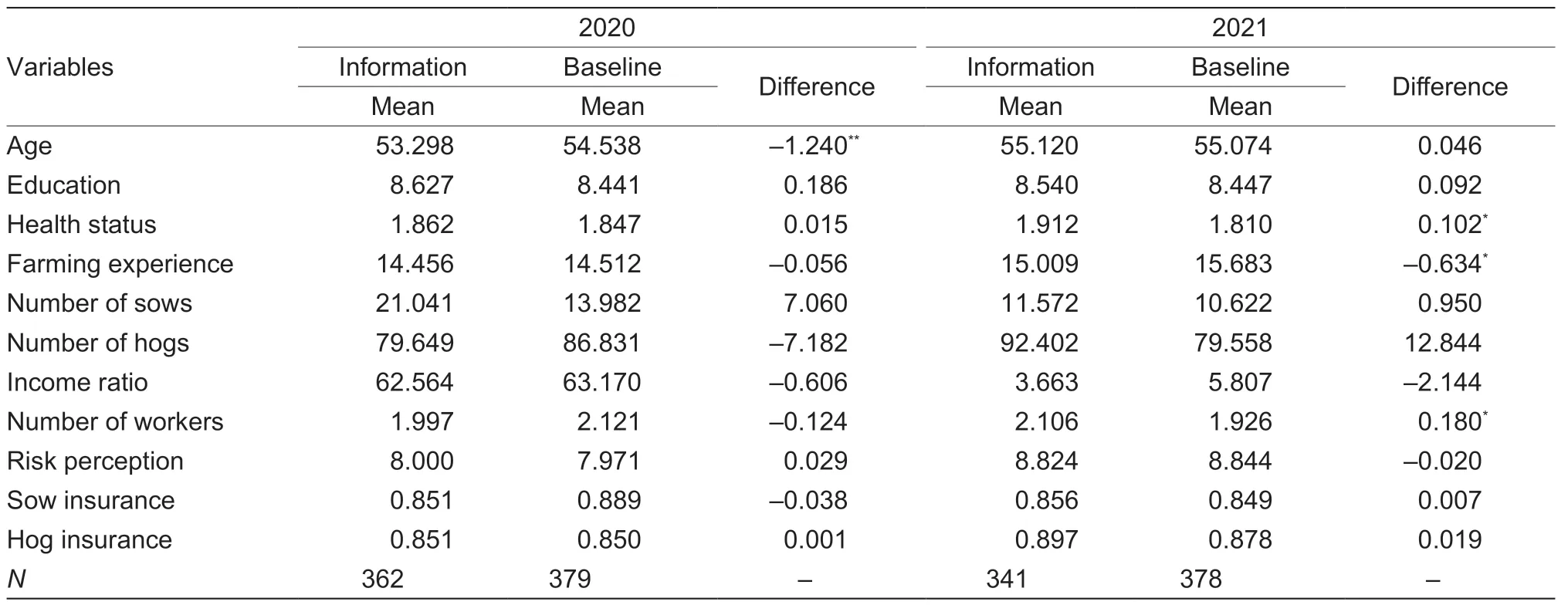

Table 4 presents the definitions of variables and Table 5 shows descriptive statistics of variables by groups2The sharp decline in the income ratio from 2020 to 2021 is mainly due to the recovery of pig production from African swine fever.On the one hand,pig farmers changed their production behavior because of the low prices,and the average number of sows was reduced,so the income ratio of pig farming decreased.On the other hand,92.77% of the farmers reported that the cost of raising pigs exceeded the market value,and they did not make any profit from raising pigs,so we set the value of the income ratio of these farmers to 0..Most demographic variables and production characteristics are balanced between information treatment and baseline treatment in 2020,except that the variable age in the information treatment is significantly younger.Data in 2021 show a similar pattern.The differences in variables such as health status,experience,and number of workers between the information treatment and the baseline treatment are marginally significant,while the differences in most variables between the two groups are insignificant.Moreover,we conducted robustness checks to show that farmers in the two groups were indifferent in understanding and predicting the COVID-19 information.Farmers’ understanding of the information might be influenced by their awareness of COVID-19 cases around them and the impact of COVID-19 on their daily lives.Therefore,we asked three questions about farmers’ awareness of COVID-19 cases in their villages,among their friends,and in Jiyuan County,as well as the impact of COVID-19 on their daily lives.Appendices B and C show no significant difference between the two groups.All in all,the above results verify the success of randomization in our experiments.

Table 4 Definitions of variables

Table 5 Descriptive statistics of variables

3.4.Empirical strategy

We estimated the impacts of information about COVID-19 on farmers’ pig production willingness using a linear probability model (LPM).An essential assumption of LPM is that the explanatory variable is strictly exogenous (Aldrich and Nelson 1984).In randomized experiments,the information allocation depended only on the die number and was independent of factors such as farmers’ characteristics and hog market characteristics.Randomly assigning information regarding COVID-19 in our study ensures the satisfaction of the above assumption.Theregression equation in our paper is as follows:

whereYiis a dummy variable,it equals 1 when farmeriplans to scale up production.The key explanatory variablelnfor_treatmentirepresents if farmeribelongs to the information treatment,andεirepresents random error.β1measures the impact of information about COVID-19 on farmers’ willingness to scale up.To test the robustness of the estimation results,we also used eq.(2) to control individual,household,and production characteristicsXiand town fixed effectsTownj.

4.Results

4.1.Impacts of information about COVID-19

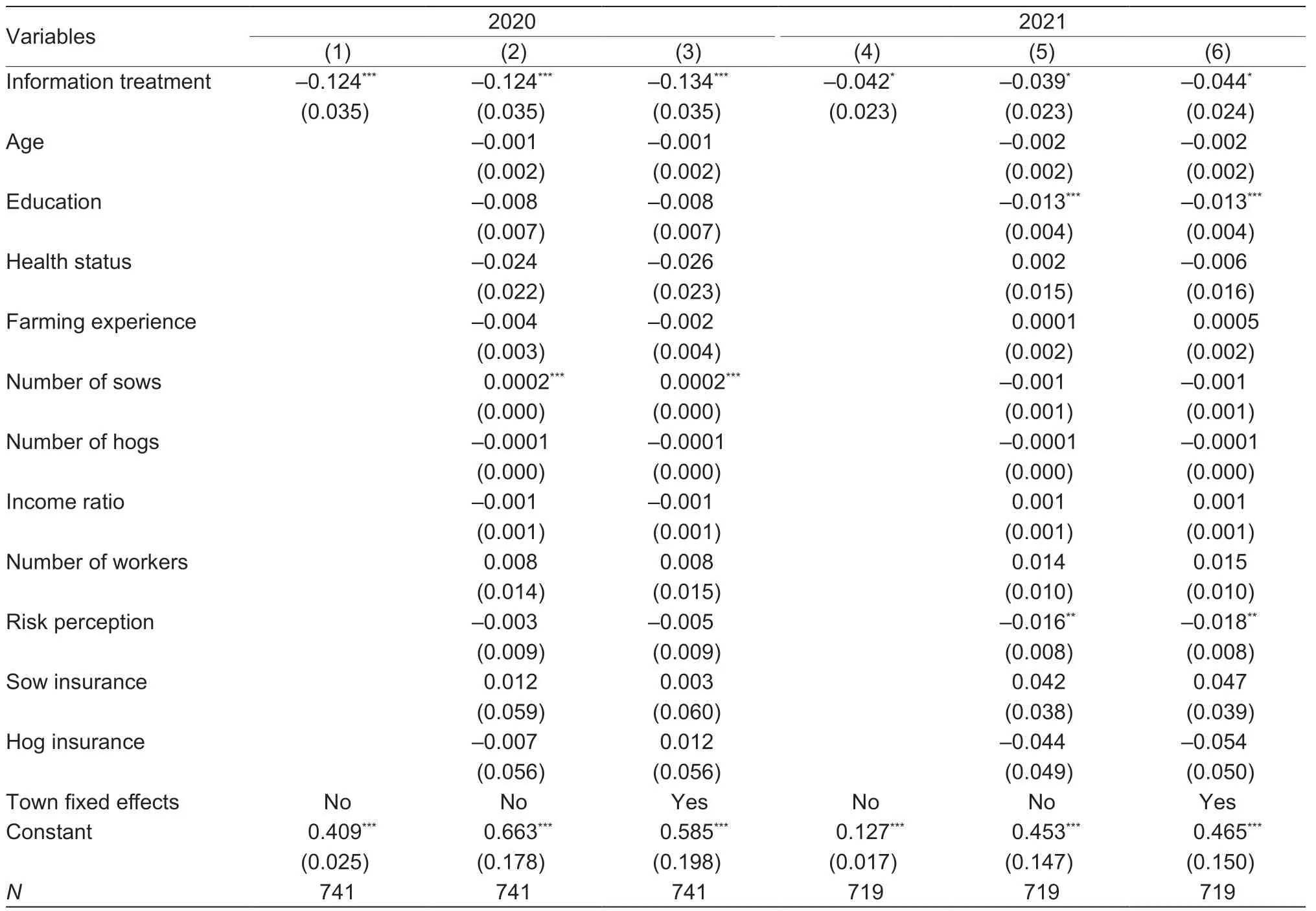

Table 6 presents results from the LPM,which also survived the logit and probit model tests (Appendix D).Columns (1)-(3) of Table 6 show regressions using data in 2020,while Columns (4)-(6) show regressions using data in 2021.Regression results based on different model specifications from Columns (1)-(3) reveal that information about COVID-19 significantly reduced pig farmers’ willingness to scale up in 2020.Additionally,the coefficients of the information treatment remain consistently close across various control variables,confirming the validity of the random assignment in theexperiments.Results in Column (3) show that,after controlling other factors,farmers who learned information about COVID-19 were 13.4% less likely to scale up production,and the treatment effect is statistically significant at the 1% level.Similar negative influences of information about COVID-19 were also found in Columns (4)-(6).However,the effect of information in 2021 drops to 4.4% and is only significant at the 10% level.

Table 6 The impacts of information about COVID-19 (linear probability model)

The treatment effects varied across two years for two possible reasons.First,endorsement information and prevailing phases of COVID-19 were different across two years.In June and July 2020,there was no vaccine available.However,COVID-19 had spread worldwide,and some regions of China also experienced sporadic outbreaks mainly penetrated from abroad.The endorsement in 2020,therefore,was that the second wave of COVID-19 might occur without a vaccine.In October 2021,the situation was different.More than 73% of the Chinese population had received two doses of vaccine.Nevertheless,the virus was evolving constantly,and new variants with stronger infectivity were identified intermittently.Hence,farmers in the information treatment were informed that COVID-19 might continue to spread despite the introduction of vaccines.Second,various other factors,especially the pork market,changed over the two years.As shown in Fig.2,pork prices were high in 2020,and farmers could make a good profit if their farms were not affected by ASF.However,pig production capacity was quickly restored,and pork was oversupplied in 2021,which led pork prices to decline sharply from 47.98 to 19.56 CNY kg-1in Henan Province.Data from MARA shows that the average loss for raising a pig was 349 CNY in October 2021,declining from an average profit of 1,025 CNY in June 2020.Therefore,farmers were more likely to scale up in 2020 and were less likely to scale up in 2021 based on economic considerations.

4.2.lnfluence of actual COVlD-19 experiences

Access to information regarding COVID-19 might affect farmers’ willingness to raise pigs through two channels.First,information regarding COVID-19 might remind them of the potential risks caused by COVID-19.Second,information regarding COVID-19 might recall farmers’ actual experiences of being affected by COVID-19.Therefore,we investigated whether farmers whose production of pigs was actually affected by COVID-19 are less willing to scale up when they learn the information about COVID-19.

We measured the actual influences of COVID-19 on farmers by asking them to answer whether their supply chain of pig feed,veterinary drugs,hired labor,or hog sales were actually affected by COVID-19.Appendix E shows the results of descriptive statistics.In terms of feed supply,44.5% of farmers in 2020 indicated they were affected by COVID-19,and the percentage dropped to 35.6% in 2021.In terms of hog sales,the proportion of indicating being affected is higher (39.4%) in 2021 than that in 2020 (29.7%).This could be attributed to the lower willingness of farmers to sell pigs in 2021 because of the low price,and farmers thought COVID-19 resulted in low prices.Worker recruitment was relatively less affected across the years.A possible reason is that most farms were run by families,and the majority of workers were family members.

We divided samples into two subsamples according to whether they were actually affected by COVID-193Farmers were classified as being actually affected by COVID-19 if they indicated that any of the four aspects of raising pigs in Appendix E were actually affected by COVID-19..In Table 7,Columns (1) and (3) show results of the subsample which was not actually affected,while Columns (2) and (4) show results of the subsample which was actually affected.As shown in Panel A,the impact of information regarding COVID-19 is greater for farms whose feed supply was actually affected by COVID-19 than farms that were not affected,and the result is significant at the 1% level.Panels B to D show results of the influence of drug supply,which are consistent with other results.Although the impact was not significant for farms affected in terms of workers hired (Panel C),the absolute values of coefficients in Columns (2) and (4) are larger.In addition,Columns (1) and (3) show that farmers not affected by COVID-19 were also influenced by the information,and this effect is due to the direct impact of the information.

Table 7 The influence of actual COVID-19 experience (Heterogeneous treatment effects)

The above analyses support our hypothesis that the information treatment effects are heterogeneous according to whether farmers were actually affected by COVID-19.Compared with farmers who were not affected by COVID-19,farmers who were actually affected were less willing to scale up when they learned information about COVID-19,which reflects that the influence of access to information regarding COVID-19 should be partially attributed to recall farmers’ negative memory of their actual experience of COVID-19.

4.3.Do farmers’ willingness in experiments predict their actual pig-raising behavior?

The Theory of Planned Behavior proposes that intentions with considerable accuracy are the most important predictor of behavior (Ajzen 1991).A variety of studies have provided empirical evidence to support the correlation from different fields (Conner and McMillan 1999;Armitage and Conner 2001;Sheeran 2002;Hagger and Chatzisarantis 2009;Kautonenet al.2013).However,empirical studies have found that farmers’ willingness (intention) does not effectively predict behavior in various areas,such as the adoption of photovoltaic agriculture (Liet al.2021),land transfer (Zhanget al.2020),theadoption of electricity-saving tricycles (Qiuet al.2022),and support for new and renewable energy (Litvine and Wüstenhagen 2011;Fanget al.2021).In terms of pig production,there is limited evidence of the relationship between farmers’ willingness and behavior.Heet al.(2022) investigated the willingness and actual behavior of pig farmers to use swine manure to produce biogas.They found a gap between willingness and behavior,and the inconsistency accounted for 47.3%.

To address the concern of the willingness-behavior gap,we investigate whether farmers’ pig raising behavior could be predicted by their willingness in experiments.The number of pigs raised by farmers at the end of 2020 was collected by a follow-up phone survey in 2021.Therefore,we combined two sources of data to test whether farmers’ willingness to scale up in the middle of 2020 predicts their actual pig-raising behavior at the end of 2020.We observed that farmers who were willing to scale up had an average of 146.75 hogs at the end of 2020,whereas farmers who were unwilling to scale up had an average of 104.50 hogs.This resulted in a mean difference of 42.25 hogs between the two groups.Table 8 shows the regression results that,compared with farmers who didn’t plan to scale up production in the experiment,farmers indicated their willingness to scale up in the experiment actually raised 47-52 more hogs at the end of 2020,which provides strong support that farmers’ willingness to scale up production in the experiment could predict their actual pig raising behavior.

Table 8 The prediction of farmers’ willingness on their pigraising behavior

5.Discussion

5.1.Sample selection bias

One concern in this study is the potential attrition bias arising from the inability to trace some farmers in the follow-up experiment,and some specific characteristics might relate to both their withdrawal and their production behavior.The sample size in our study decreased from 1,111 in 2020 to 995 in 2021.We used the two-stage Heckman model (Heckman 1976,1979) to correct the potential attrition bias due to farmers’ withdrawal.Table 9 reports regression results from the two-stage Heckman model.Column (1) of Table 9 shows the result of the first stage regression and finds that farmers with better health status in 2020 were more likely to be followed in 2021.Column (2) of Table 9 shows the result of the second stage.The statistic ofλis insignificant,which means that this sample selection bias is not a significant issue.Also,the coefficient of information treatment in 2021 is very close to the estimation of baseline regression (-0.044,Column (6) of Table 6).

Table 9 Heckman correction model estimates

In addition,we collected information from farmers who chose to withdraw from pig raising.In 2020,only 0.32% of farmers (one farmer) withdrew because of COVID-19,and 72.84% of farmers withdrew before the outbreak of COVID-19 because of ASF.In 2021,nine farmers withdrew because of COVID-19,and 49 farmers withdrew because of low pork prices.Therefore,COVID-19 was not the main reason for farmers’ withdrawal,and the sample selection did not result in much estimation bias.

5.2.The experimental design

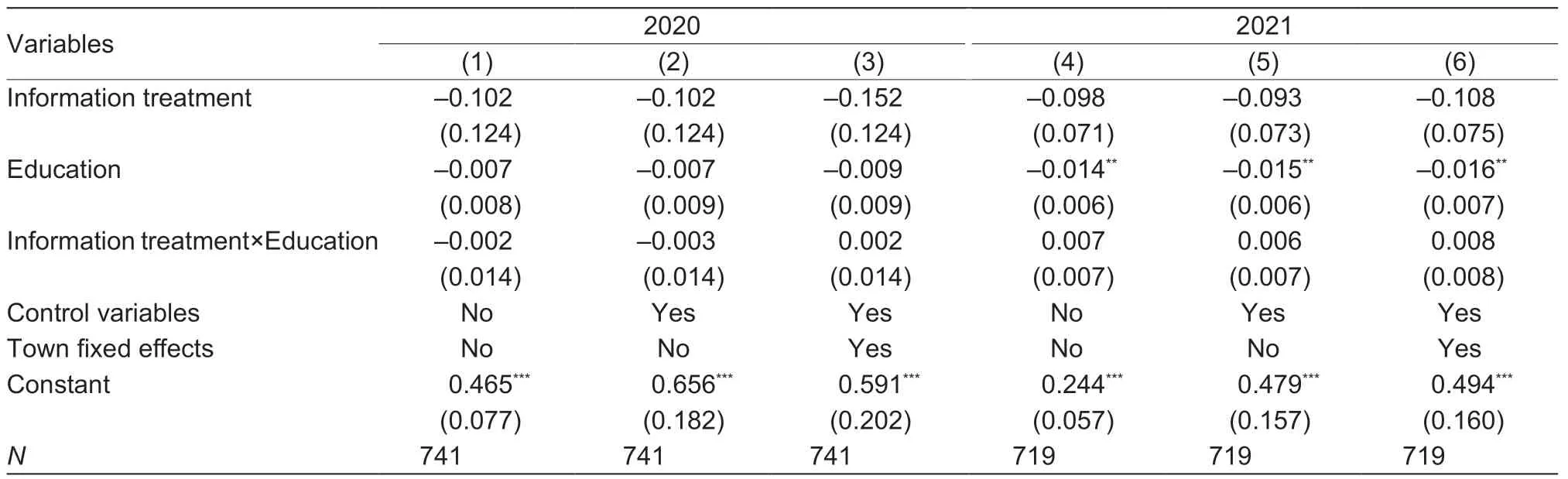

The information treatments in our study are two endorsements of COVID-19.Since the endorsements are quite simple,farmers in the baseline treatment perhaps already know that COVID-19 might prevail again and last for a long period of time,which may lead us to overestimate the impacts of negative information.In order to test whether there exist biased results due to farmers learning information regarding COVID-19viaother channels,we hypothesize that farmers with highereducation levels are more likely to learn information about COVID-19 through the Internet or media.If this hypothesis holds,the interaction term coefficient between information treatment and education should be significant.Thus,we modify eq.(2) to include an interaction term based on the information treatment variable and farmers’ education.However,as shown in Table 10,the interaction term coefficients are insignificant in both years.The results reject that information acquisition ability varies with farmers’ education which results in the overestimated effects of information regarding COVID-19 in experiments.

Table 10 Robustness check of the experimental design

5.3.The long-term influence of information regarding COVID-19 in experiment

The last concern is that the production willingness of farmers in 2021 might be affected by their participation in the information treatment in 2020.We run at-test to test whether there is a significant difference regarding farmers’ production willingness between Group I and Group II in 2021 (Appendix F).The result shows that the difference is not statistically significant between the two groups and rejects the long-term effect of information regarding COVID-19 in the 2020 experiment.Moreover,to exclude the potential long-term effect of information regarding COVID-19 in 2020,we restrict our sample to farmers who never participated in the information treatment in 2020.If the long-term effect of information exists,the absolute value of the estimated impacts using a restrictive sample should be smaller than the baseline regression (0.044,Column (6) of Table 6).However,the results in Appendix G show that for farmers who did not receive information regarding COVID-19 in 2020,their willingness to scale up declined by 6.3% after learning the information regarding COVID-19 in 2021.The absolute value of estimation (0.063) is larger than 0.044,suggesting no spillover effect of the information treatment in 2020,and the baseline estimations in 2021 are robust.

6.Conclusion

This study explores whether providing COVID-19 information influences farmers’ pig production willingness.Our findings are threefold.First,information about COVID-19 significantly negatively affects farmers’ willingness to scale up.In 2020,the information that a second wave of COVID-19 might occur without effective vaccines reduced farmers’ willingness to scale up by 13.4%.In 2021,the information that COVID-19 might continue to spread reduced famers’ willingness to scale up by 4.4% despite the vaccine’s introduction.The varied treatment effects between 2020 and 2021 are mainly due to different endorsements,stages of COVID-19,and changes in the pork market.Second,the effects of access to information regarding COVID-19 varied with farmers’ experience with COVID-19.Specifically,compared with farmers whose production was not affected by COVID-19,farmers who were affected by COVID-19 were less likely to scale up.Last but not least,we present evidence to show that farmers’ willingness to scale up could predict their actual production behavior.

Our findings have three policy implications.First,our results indicate that information about COVID-19 significantly affected farmers’ production willingness in the early stages of COVID-19 and also later when the outbreak was under control.Moreover,farmers’ production willingness could further predict their actual production behavior.Therefore,governments should provide farmers with timely and accurate information to help them make informed decisions and adjust their production plans.Second,we highlight the important role of farmers’ actual COVID-19 experience.In order to mitigate the negative impact of the pandemic in its early stages,governments should quickly implement measures to support efficient transportation systems,and farmers should consider feed storage options to ensure preparedness.Third,by comparing the results of the 2020 and 2021 surveys,we find that the condition of the pig market is a crucial factor influencing farmers’ production intentions and behavior.China’s pork market is vulnerable,with pork supply and prices fluctuating frequently.In 2021,the increased supply has led to a substantial decline in pork prices.This and rising production costs have resulted in financial losses for almost all pig farmers.Policymakers should implement measures to stabilize the market supply and pork prices and ensure a balance supporting farmers and consumers.

This study also has several limitations.First,our findings are limited to Jiyuan County and face challenges regarding external validity.Second,providing COVID-19 information prior to farmers expressing their plans to expand may lead to the experimenter demand effect (EDE)4The experimenter demand effect (EDE) refers to participants’ behavior changes when they infer the purpose of experiments and respond to help confirm the researchers’ hypothesis (Orne 1962;Zizzo 2010)..If this effect exists,our estimation results might overestimate the impacts of information in experiments.Finally,various factors other than endorsements,the stages of COVID-19,and changes in the pork market have changed over the two years.These factors potentially contribute to the heterogeneous effects across the two years.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the National Social Science Fund of China (23&ZD045),the Humanities and Social Sciences Youth Foundation of the Ministry of Education of China (21YJC790087),the Center for Social Welfare and Public Governance of Zhejiang University,China,and the Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Universities,China.

Declaration of competing interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Appendicesassociated with this paper are available on https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jia.2023.11.034

Journal of Integrative Agriculture2024年4期

Journal of Integrative Agriculture2024年4期

- Journal of Integrative Agriculture的其它文章

- OsNPF3.1,a nitrate,abscisic acid and gibberellin transporter gene,is essential for rice tillering and nitrogen utilization efficiency

- Fine mapping and cloning of the sterility gene Bra2Ms in nonheading Chinese cabbage (Brassica rapa ssp.chinensis)

- Basal defense is enhanced in a wheat cultivar resistant to Fusarium head blight

- Optimized tillage methods increase mechanically transplanted rice yield and reduce the greenhouse gas emissions

- A phenology-based vegetation index for improving ratoon rice mapping using harmonized Landsat and Sentinel-2 data

- Combined application of organic fertilizer and chemical fertilizer alleviates the kernel position effect in summer maize by promoting post-silking nitrogen uptake and dry matter accumulation