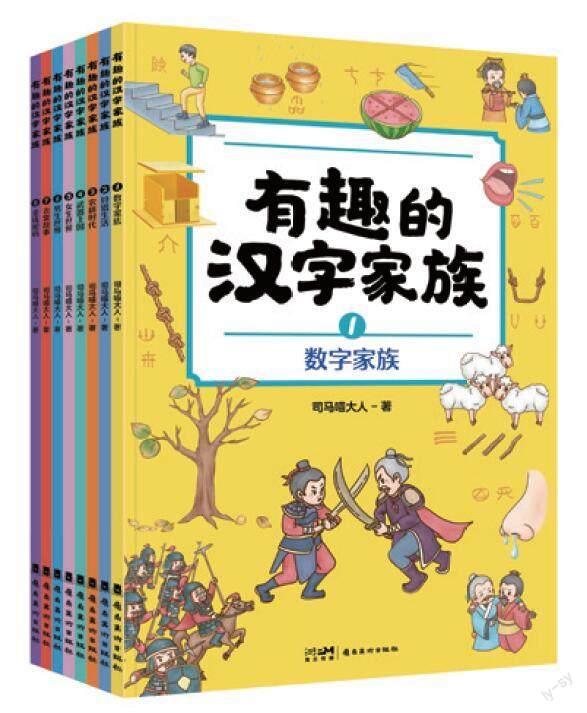

The Fascinating Chinese Character Family

This series is an engaging read about Chinese characters, explaining their origins and the logic behind their creation. It allows readers to grasp the essence of Chinese character culture and appreciate the ancient art of character creation. The series is divided into eight mini-volumes, each focusing on eight major categories of common everyday objects. It introduces over 260 key characters studied in elementary school and more than 200 practical idioms for elementary students.

Lord Sima Miao

Lord Sima Miao was originally named Lu Jianguo, a member of the China Writers Association. He formerly worked as a middle school teacher and contributed to the development of middle school textbooks in Tianjin, Shanghai, and Hong Kong. He has served as a question setter for Shanghais middle and high school exams and has been invited several times to give lectures on Chinese characters to elementary and middle school students.

The Fascinating Chinese Character Family narrates the wondrous tales of Chinese characters. Our first volume begins with numbers.

As a student, Teacher Sima wondered: why does the math teacher teach the Arabic numeral “1” as a vertical line, while the language teacher writes it horizontally as “一”?

Later, after learning Roman numerals, he noticed their “Ⅰ” is also a vertical line. It seemed odd. Why are others “1” vertical while ours is horizontal?

This question sparked Teacher Simas earliest exploration into the mysteries of writing.

Why are the numbers 123 written in Chinese as “一二三”?

The answer traces back to a calculation tool used by the ancient Huaxia people -- the counting rod.

What is a counting rod? Its essentially small sticks of similar length and thickness, made from bamboo, wood, or even animal bones and elephant tusks. Our ancestors put these small sticks in cloth bags, tied them around their waists, and took them out whenever they needed to count. This was called counting rods.

Our ancestors would lay one stick horizontally on the ground, marking the origin of the character “一” (one).

All numbers are related to how the people who invented them counted. Why are Indian numbers, or Arabic numerals, written as “1”? Actually, they counted using the angles in shape; closely examining “1” reveals it has one angle. Continuing this pattern, “2” has two angles, “3” has three angles, and so on.

So, how numbers are written is closely related to ancient mathematical calculation tools.

But, when this problem was solved, a new problem came up. Some students asked: In Chinese class, we learn classical Chinese, and there are many ones in it, such as “one man guards the pass, ten thousand men cannot cross,” “one defeat and ruin,” “how bitter is the womans cry.” Here, does “one” also express the meaning of numbers?

Here, Teacher Sima would say that the ancients were very smart; they invented a character and only had one usuage for it. If it was one character one use, those creating new characters would be busy to death. So, a character expressing multiple meanings is a very common in Chinese characters.

For example, this “one,” the ancients thought: If I caught a sheep today and another tomorrow, and the two sheep have the same color and look similar, how should I express it?

Thats right! Its “the same.”

For example, if I caught more sheep this time and put them on a hillside to graze, it could be said to be “a hillside of sheep.” Here, “one” has the meaning of whole, all, everything, etc.

Further, I have so many sheep, and I am happy in my heart. I can also use this “one” to express this kind of rising emotion. For example, in The Officer at Stone Moast by the Tang Dynasty poet Du Fu, there is a sentence: “How angry is the officers shout! How bitter is the womans cry! (吏呼一何怒,婦啼一何苦)” Is “one” the officer and the old woman counting numbers here? Of course not; it is similar to “how” in meaning.

In ancient Chinese philosophical thought, Laozi, the founder of Taoism, had a special explanation for this character “one.” He said: “The Tao is established in one, one produces two, two produces three, three produces all things.” What does this mean? “One” here represents the original chaotic world. From the chaotic world, heaven and earth (“two”) were born, and then from between heaven and earth, humans (heaven, earth, humans) were born, and then all things were born. One is the beginning of all things.

Why is “four(四)” not written as four horizontal lines?

There are always many stories happening in this world. The ancients picked up their pens and wrote numbers, drawing a horizontal line as “one,” drawing two horizontal lines as “two,” and drawing three horizontal lines as “three.” But when it came to “four,” why was it suddenly not four horizontal lines?

In fact, the ancients had done this before; the four horizontal lines of “four” existed from the Shang Dynasty until the Han Dynasty.

Then, when did it change to the current way of writing?

In the Spring and Autumn and Warring States periods, two more alternative ways of writing appeared.

One of them, like a round melon or cake with a triangle inside, cutting the melon or cake into four pieces.

There is also another way of writing: an oval shape with a stroke and a dot drawn from the inside.

Mr. Ma Xulun, an educator in the Republic of China era, proposed a view. He thought: “Four” might not originally mean a number, but an action.

What action? This oval shape; it looks like a nostril, and the stroke and the dot, like two strings of snot, flow out of the nostril. That is to say, the original meaning of “four” (四) is snot flowing out. This meaning, today, is inherited by another similar character, “si” (泗).

In this way, it should be that the ancients thought that drawing horizontal lines one by one was too troublesome, so when they came to the number “four,” they used the method of “homophones,” that is, they took the “four” with a similar pronunciation. They made it a number, and the original meaning of “four,” then created another “si.”

Such a change had already appeared in the Spring and Autumn Period. The Book of Songs says: “From the eyes say tears, from the nose say snot.” That is, what flows out of the eyes is called tears (that is, “ti”), and what flows out of the nose is called snot (that is, “si”).

Therefore, Ma Xuluns view is consistent with the record of the Book of Songs.

And “four,” although it was borrowed to be a number, occasionally it would also be borrowed by the ancients to be a homophone, for “si” (駟). For example, the Garden of Anecdotes has such a sentence: “One word is wrong, four horses cannot catch up.” If a word is wrong, then it can never be changed, even if you drive a carriage pulled by four horses (that is, “si”), you cant catch up!

Then what about “five” (五)?

If you travel to the era of character creation, the ancients will tell you: “Five” is an extreme number. What is an extreme number? It is the largest number.

Lets see how the character “five” was written in the Shang Dynasty.

First, the oldest way of writing five, was drawing five horizontal lines.

This is easy to understand, drawing a horizontal line is “one,” drawing five horizontal lines is “five,” isnt it? But we also said before, this way of creating characters is not sustainable. So this way of writing rarely appeared after the Warring States Period.

Another way of writing it is completely different --

Two horizontal lines, one above and one below, and an “Χ” in the middle; what does this mean?

The ancient philosophers gave a very mysterious explanation to the character “five,” saying that the upper horizontal line represents heaven, the lower horizontal line represents earth, and the “Χ” in the middle is the intersection of all things between heaven and earth. Therefore, the character “five” represents all material things in the world and is the largest number. All the things in the world can be classified and summarized into five elements, namely metal, wood, water, fire, and earth -- still “five!”

The earliest dictionary in the world, the Analytical Dictionary of Characters, compiled in the Eastern Han Dynasty, explained it this way. But the problem here is, standing on the threshold of civilization, where would the ancient humans have such a mysterious philosophical thought? Isnt it a later interpretation?

So there was a second explanation: “Χ” was a crossroad. The ancients came to crossroads and were confused about which way to go. Is it this way or that way?

This confusion is just like the ancient people counting. Tying knots to record things, when they tied the first four knots, they might still remember clearly why they did it, but when they came to the fifth knot, they would be puzzled: What does this mean? Is it that I lent five eggs to Old Wang, or Old Wang lent me five eggs?

So, the ancient character makers, drew an Χ on the ground, representing a crossroad.

(Early Shang Dynasty)

(Late Shang Dynasty)

The character “five” in the early Shang Dynasty was an “Χ.” Then they gradually added other parts.

Lin Yiguang, a scholar from Fujian in the Republic of China era, proposed a third opinion: “Five” actually is the sunlight shining at noon; that is, the original way of writing “noon” now. But later, people used this character as a number, and had no choice, so they moved over another homophone “noon,” which originally meant a pestle (a stick used for pounding rice, 舂杵, chōng chǔ).

If this opinion is valid, it also means that what we write now as “morning, noon, afternoon” originally was written as: “upper five, middle five, lower five.”

From the expression mode of pictographs, Teacher Sima also agrees with Mr. Lin Yiguangs opinion. But at present, this is still only a minority opinion.

After the Han Dynasty, this number became more and more square and finally became what it looks like today.

So, the original meaning of the character “five” is crisscrossing. For example, in this sentence from the Book of Songs: “A garment of lambs skin, finely sewn with plain silk, using five unique stitching styles.” It cannot be explained as, “Wearing a lamb fur robe, the silk is sewn in five places,” But rather, “Wearing a lamb fur robe, the silk is sewn crisscrossing, the quality is very good.”

The Fascinating Chinese Character Family (Total Eight Volumes)

Lord Sima Miao

Lingnan Fine Arts Publishing House

August 2023

198.00 (CNY)

- 中国新书(英文版)的其它文章

- Wen Zhengming: A Suzhou Elegance Legend

- The Legend of the City

- Candlelight Tales in the Whitewashed Hall

- Jiangnan Medical Sage Yu Jiayan

- The China Path -- A Unique Modernization Journey (English Edition) Published and Distributed

- 2023 China Shanghai International Children’s Book Fair Concludes