学校联结与抑郁的关系:一项三水平元分析

孟现鑫 陈怡静 王馨怡 袁加锦 俞德霖

摘 要 以往关于学校联结与抑郁关系的理论和实证研究结果均不一致。为明确两者间的整体关系, 探索造成分歧的原因, 对纳入的87项研究进行了三水平元分析。结果发现, 学校联结与抑郁存在显著负相关(r = ?0.39, df = 205, p < 0.001)。此外, 学校联结和抑郁的关系受被试性别、年龄、抑郁测量工具、研究數据属性的调节, 但不受学校联结测量工具、文化类型、发表年份的调节。本研究首次使用三水平元分析技术整合了学校联结与抑郁的关系, 理论上为两者关系提供了阶段性定论, 实践上为预防和干预个体抑郁提供了参考依据。

关键词 学校联结, 抑郁, 三水平元分析, 社会控制理论, 社会计量器理论, 自我决定理论

分类号 R395

1 前言

世界卫生组织(World Health Organization, WHO)指出, 抑郁是加重各国疾病负担的主要因素, 全球约有2.8亿人被抑郁困扰, 占总人口的3.8% (World Health Organization, 2023)。抑郁不仅会导致个体学习和工作效率低下, 而且会导致人际交往障碍甚至自杀(Thapar et al., 2012; Kieling et al., 2019)。为了有效预防和干预抑郁, 以往研究探讨了诸多与其密切相关的因素, 其中学校联结是备受关注的因素之一(He et al., 2019; Joyce & Early, 2014; Shochet et al., 2006)。学校联结(School Connectedness)是指学生在学校中所感知到的接纳、尊重、支持和包容(Goodenow, 1993), 反映了学生对学校的认知以及与校内成员的情感联系程度(殷颢文, 贾林祥, 2014)。目前, 多数理论认为学校联结是降低抑郁水平的保护性因素(Gerard & Booth, 2015; Leary, 2005; Sandler, 2001); 但也有理论认为, 学校联结对抑郁没有保护作用, 甚至起反作用(Datu et al., 2023; Davis et al., 2019; Loukas et al., 2006)。与此一致, 学校联结与抑郁的实证研究既有报告负相关结果、正相关结果, 也有报告无相关结果。综上, 学校联结与抑郁的关系在理论观点和实证研究上均存在分歧。为解决学校联结与抑郁关系间的争议, 本研究采用元分析技术(meta-analysis)定量整合学校联结与抑郁的关系, 并且分析可能影响二者关系的因素, 从而为抑郁的预防和干预提供依据。

1.1 学校联结与抑郁的关系及其理论模型

目前, 主要有社会控制理论(Social Control Theory)、社会计量器理论(Sociometer Theory)、自我决定理论(Self-Determination Theory)和社会支持的源一致理论(Source Congruence Theory)论及了学校联结与抑郁的关系。

社会控制理论认为个体与社会组织的联结程度越强, 该组织对个体的心理和行为的影响就越大(Hirschi, 1996)。根据这一观点, 个体的学校联结越强, 其情绪与健康受学校的影响越大。具体而言, 学校联结程度高的个体更愿意遵守校纪, 能与老师、同学形成更好的联结以获得情感支持, 从而有助于缓解或削弱压力事件产生的消极情绪, 降低患有抑郁的风险(McLaren et al., 2015)。McLaren等人(2015)发现, 学校联结可以有效促进积极的同伴联结, 从而减少抑郁的产生。社会计量器理论提出, 那些认为人际关系重要的个体倾向于建立积极的人际关系, 从而获得更多的社会支持、产生较少的消极情绪(Leary, 2005)。学校联结程度高的个体往往能够认识和感受到人际关系的重要性, 这有助于减少其消极情绪和罹患抑郁的风险。Shochet等人(2011)发现, 在校感受到的人际关系质量和被接纳程度越高, 个体的抑郁水平越低。自我决定理论认为个体希望自己在所处的环境中能感受到来自他人的爱和关怀, 感受到自己属于组织中的一员。这种归属感的满足有助于降低个体的消极情绪和提高个体的心理健康水平(Ryan & Deci, 2017)。学校联结能满足个体对归属感的需要, 从而缓解压力产生的不良情绪, 降低个体罹患抑郁的风险。与此相一致, Parr等人(2020)发现积极学校联结可以通过满足个体的一般归属感来降低抑郁水平。

与社会控制理论、社会计量器理论和自我决定理论的观点不同, 社会支持的源一致理论认为, 若压力源和社会支持的来源一致时, 社会支持对压力的缓冲作用可能无效(Lebow, 2005; Rueger et al., 2016)。具体而言, 与学校的联结可能促使个体更关注来自学校领域的他人评价(Vannucci & McCauley Ohannessian, 2018), 而当引起抑郁情绪的压力来自学校时(比如, 学业和人际关系), 学校联结程度高的个体可能会抑制抑郁情绪的表达以符合学校期待(周文洁, 2013)。此时, 学校联结不仅可能无法减少抑郁情绪, 甚至导致抑郁情绪的累积, 表现为社会支持的反转缓冲效应(Reverse Buffering Effects of Social Support) (Lebow, 2005; Rueger et al., 2016)。与此一致, Datu等人(2023)的研究发现在期末考核阶段, 随着学校联结程度的提高, 学生报告了更高的抑郁水平。

根据以上理论, 学校联结通过与其他因素的相互作用, 影响个体的抑郁水平。但是学校联结与抑郁的具体关系如何尚不清楚, 两者的关系具体受哪些因素影响仍有待讨论。

1.2 学校联结与抑郁关系的调节变量

学校联结与抑郁的关系存在不一致的结果, 可能与研究对象特征(性别、年龄)、研究的测量因素(测量工具、研究数据属性)、研究背景特征(文化、时代)有关。

性别可能调节学校联结与抑郁的关系。在社会化过程中, 女性被鼓励依赖和与他人建立亲密关系(Davis et al., 2019), 而男性则被鼓励独立和自主(Bakan, 1966; Barbee et al., 1993)。在学校中, 女性比男性更倾向从教师和同学等校内成员中寻求支持以应对压力产生的不良情绪(Yang et al., 2021)。因此, 与男性相比, 学校联结对女性抑郁的影响可能更大。与此相一致, He等人(2019)发现, 学校联结对女性抑郁的影响程度更大。综上, 本研究假设相比于男性, 学校联结对女性抑郁的影响更大。年龄也可能影响学校联结与抑郁的关系。随着年龄增加, 来自学校的压力增强(如学业压力、同伴竞争等), 这会降低个体对学校的认同和对同伴关系的维护, 进而削弱个体的学校联结水平(Oelsner et al., 2011), 导致学校联结对个体的抑郁保护作用降低(Henrich et al., 2005; Xu & Fang, 2021)。与此相似, Rose等人(2022)发现, 相比中学生, 学校联结对小学生心理健康的保护作用更大。综上, 本研究假设随年龄增长, 学校联结对抑郁的保护作用减弱。

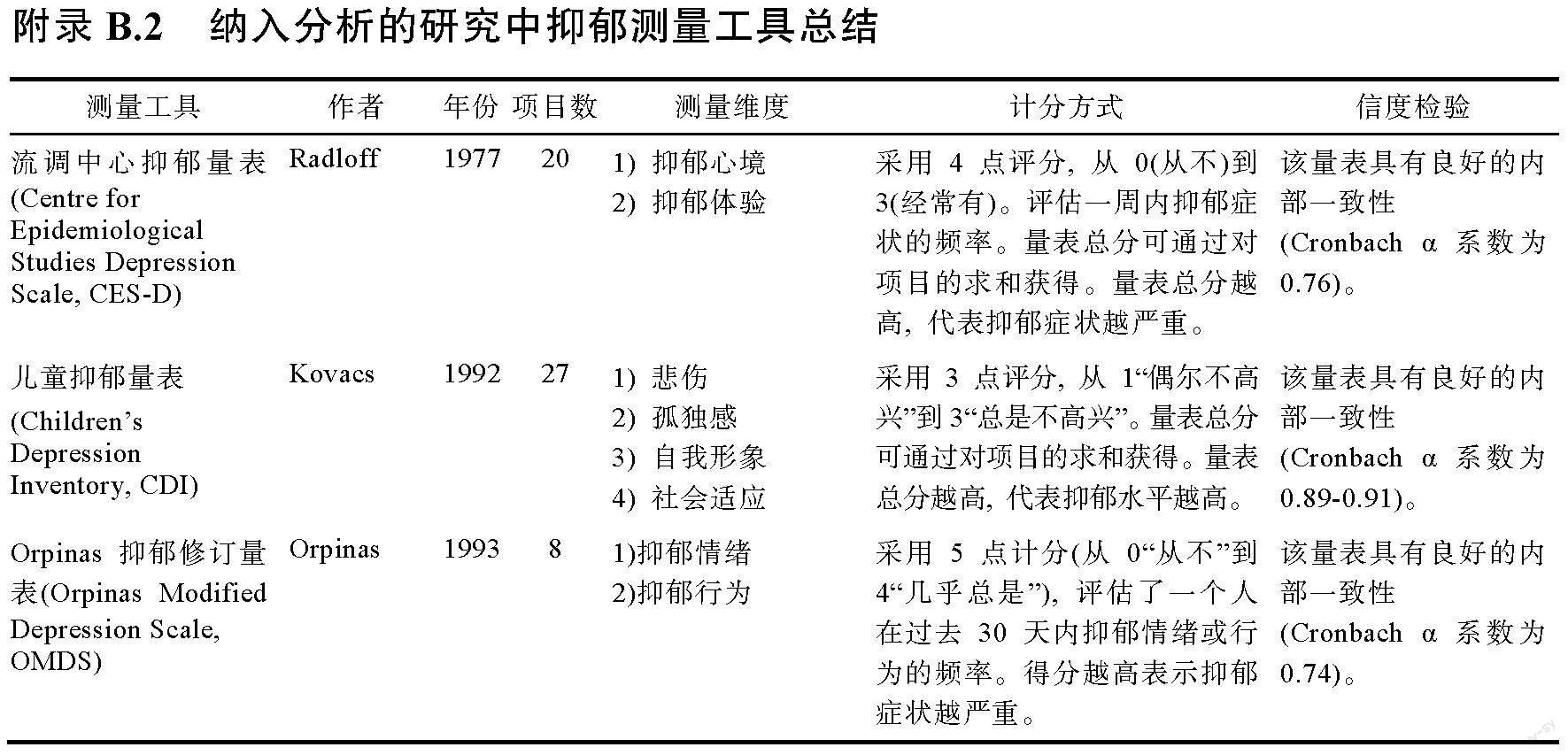

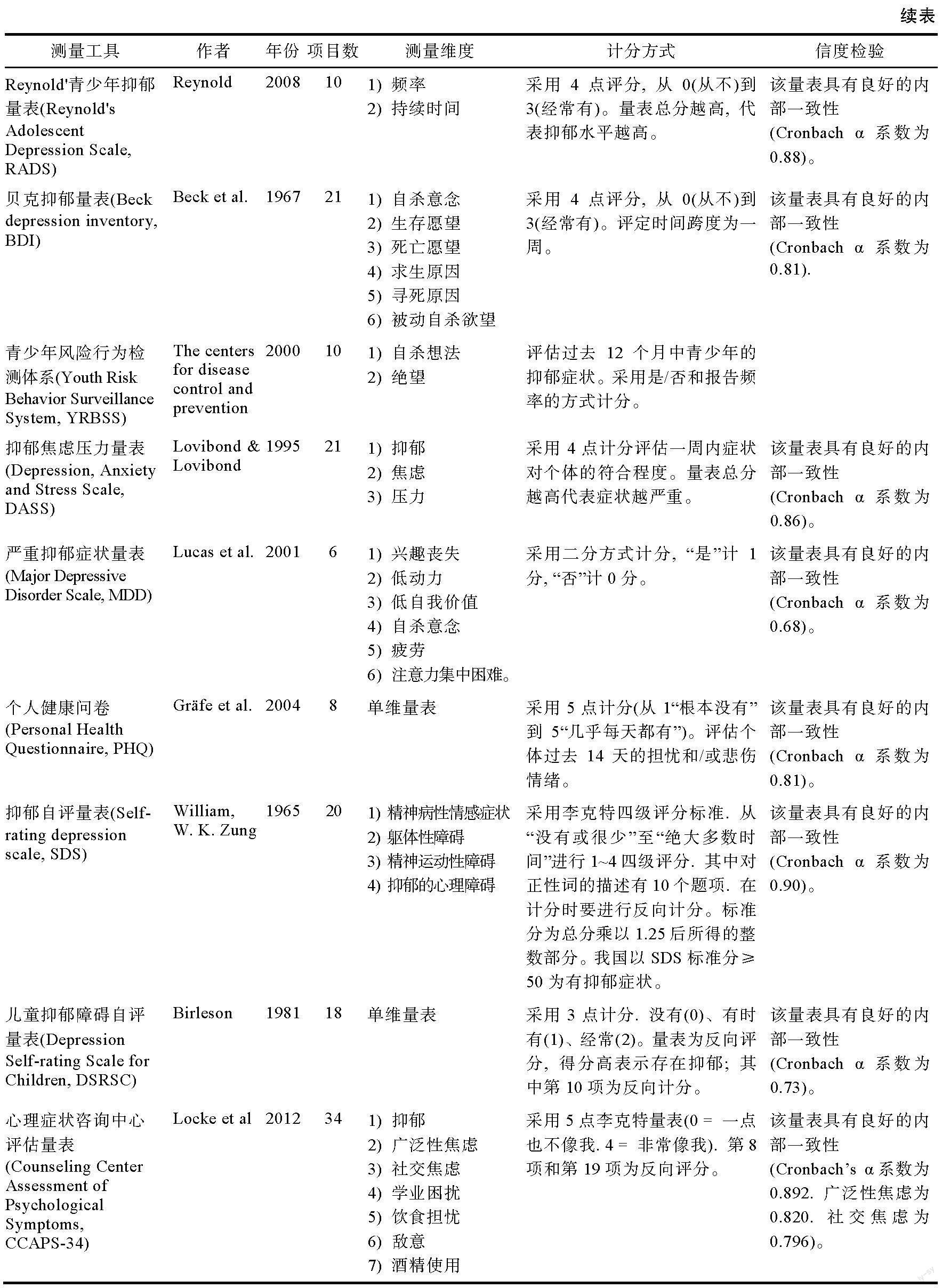

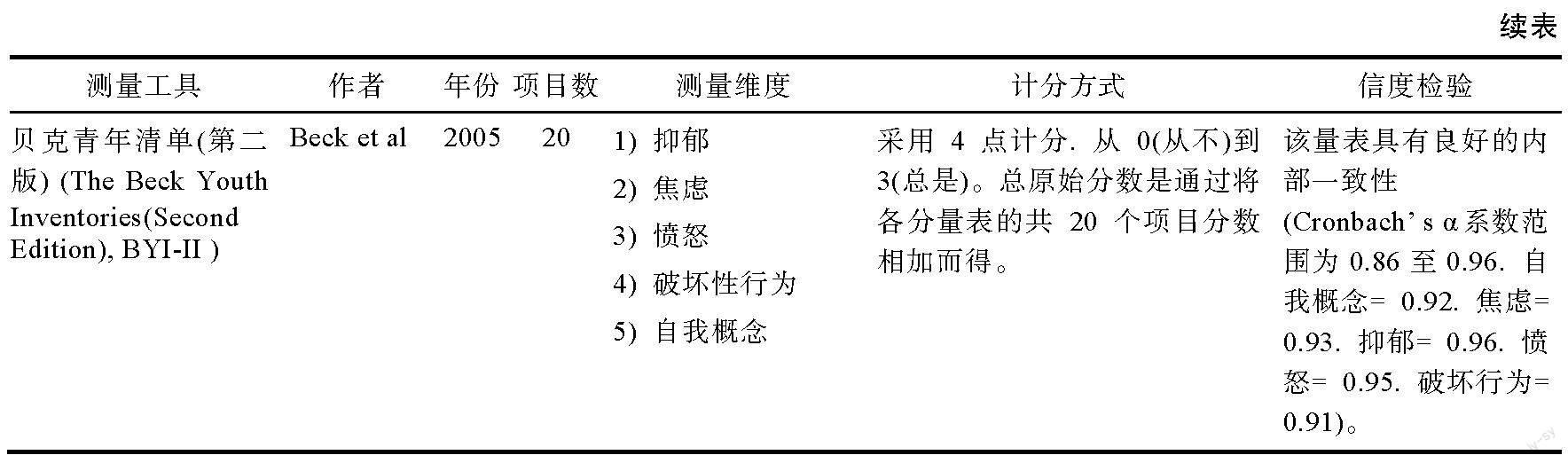

研究的测量因素(测量工具、研究数据属性)可能影响学校联结与抑郁的关系。测量工具可能调节学校联结与抑郁的关系。测量学校联结的工具主要有学校归属感问卷(Psychological Sense of School Membership Scale, PSSM)和学校联结量表(School Connectedness Scale, SCS)。PSSM量表由18个项目组成, 它测量的是学生在学校所感知的被接纳程度、师生关系和同伴关系(Goodenow, 1993)。SCS量表由6个项目组成, 它测量的是学生学校归属感与教师支持(Resnick et al., 1997)。不同学校联结的测量工具在内容和项目数量上均有不同, 这可能影响测量的结果。其次, 测量抑郁的工具主要有儿童抑郁量表(Childrens Depression Inventory, CDI)、流调中心抑郁量表(Centre for Epidemiological Studies Depression Scale, CES-D)和Orpinas抑郁修订量表(Orpinas Modified Depression Scale, OMDS)。CDI由27個项目组成, 它主要测量的是儿童悲伤、孤独感、自我形象和社会适应(Sitarenios & Kovacs, 1999); CES-D由20个项目组成, 它测量的是一般人群一周内抑郁症状的频率, 侧重评估抑郁的心境和体验(Radloff, 1977); 而OMDS由8个项目组成(Orpinas, 1993), 它主要测量的是个体过去30天的抑郁情绪和抑郁行为。各抑郁量表的结构和测量内容不同, 这可能影响学校联结与抑郁的关系。因此, 本研究假设学校联结的测量工具和抑郁的测量工具均能调节学校联结与抑郁的关系。

研究数据属性可能调节学校联结与抑郁的关系。根据数据属性不同, 研究数据可以分为横断数据和纵向数据。前者是指研究变量均在同一时间点测量并获取的数据; 后者是指研究变量在不同时间点测量并获取的数据(陈春花 等, 2016)。数据属性能够对变量关系造成较大影响, 具体而言, 纵向数据比横断数据具有更强的因果关联性(张建平 等, 2020)。与横断数据相比, 变量间的关系在纵向数据中往往呈现衰减或累积效应。目前多项纵向研究发现, 随着数据收集时间推移, 学校联结与抑郁的负相关程度减弱(Goering & Mrug, 2022)。这表明学校联结和抑郁的关系在时间上可能存在衰减效应。因此, 本研究假设, 相较于横断数据, 学校联结与抑郁在纵向数据中相关程度更小。

研究背景特征(文化、时代)可能影响学校联结与抑郁的关系。就文化因素而言, 中国集体主义文化强调人的互依性; 西方个人主义文化强调人的独立性(黄梓航 等, 2018; Hofstede, 1980)。与重视个体自由选择的西方文化相比(黄梓航 等, 2018; Hofstede, 1980), 中国文化下的个体普遍为集体主义文化的依存型自我构念, 他们更关注自己与他人的联结, 更渴望被集体接纳和支持(Chen et al., 2003; Markus & Kitayama, 2014)。因此, 相比于西方, 积极的学校联结更有助于中国个体的心理社会适应, 减少抑郁情绪。与此相似, 有研究表明, 相较于个人主义文化, 集体主义文化下积极的情感联结与个体心理健康水平相关程度更大(Park et al., 2013)。因此, 本研究假设相较于西方文化, 在中国文化下学校联结与抑郁的相关程度更强。

就时代因素而言, 在生态系统理论中, 时间系统(chronosystem)强调应当将时间和环境相结合来考察个体的心理和行为发展的动态过程。随时代发展与社会变迁, 来自学校的压力增加(如学业压力、同伴竞争等) (俞国良, 王浩, 2020), 这在一定程度上将削弱学校联结对抑郁的保护作用。因此, 本研究假设随发表年份增长, 学校联结与抑郁的相关程度减弱。

1.3 研究目的与研究问题

综上, 本研究采用元分析技术对现有学校联结与抑郁关系的研究进行梳理和分析, 从宏观的视角定量确认学校联结与抑郁关系的强度以及潜在影响因素。这在理论上有利于澄清争议, 在实践上可以为抑郁的干预措施提供证据支持。本研究将运用元分析方法关注两个核心问题:其一, 学校联结与抑郁是否相关以及相关程度如何; 其二, 探讨两者关系是否受到研究对象特征(性别、年龄)、研究的测量因素(测量工具、研究数据属性)、研究背景特征(文化、时代)的调节。

2 研究方法

为保证元分析的系统性和可重复性, 本研究根据PRISMA 2020声明进行文献检索、筛选、编码、质量评价以及发表偏倚评估, 并报告结果(Page et al., 2021)。

2.1 文献检索与筛选

本研究旨在探讨学校联结与抑郁的关系。目前, 学校联结与学校归属感在研究中经常互换使用(Baumeister & Leary, 1995; Goodenow & Grady, 1993; Libbey, 2004; Korpershoek et al., 2020)。因此, 为保证纳入的文献足够全面, 本研究首先在检索中文数据库时(中国知网、万方期刊数据库及维普期刊数据库), 将关键词“学校联结” “学校归属”分别与“抑郁”组合进行检索; 其次在英文数据库中(Web of Science, PubMed和Science Direct)以关键词“school connectedness” “school belonging”分别与“depress”或“depression”组合进行检索; 最后, 将文献阅读时发现的相关文献予以补充。检索截止日期为2023年6月19日, 最终获得文献1131篇。

使用EndNote X9导入文献并按照如下标准筛选: (1)文献类型为量化实证研究, 排除理论综述、会议摘要、个案研究以及质性研究; (2)只纳入报告了学校联结与抑郁得分之间的相关系数(r)的研究; (3)样本量明确; (4)数据重复发表仅选其中一篇, 如学位论文以期刊论文形式发表在学术刊物上且报告了数据, 则以发表的期刊论文为准, 反之采用学位论文的数据; (5)如果在符合本研究主题的原始研究中没有报告符合要求的效应量, 但向作者索要后获得相关系数r的, 也纳入分析。文献筛选流程见图1。

2.2 文献编码与质量评价

首先, 每项研究根据以下特征由两位作者独立进行编码: (A)作者; (B) 研究数据属性(横断数据/纵向数据); (C)发表年份; (D)文化类型(参照Hofstede (1984)报告的文化数据, 将样本中的美国、澳大利亚、加拿大、英国、德国归类为西方国家); (E)性别(女性在样本中的百分比); (F)平均年龄(测量抑郁时样本的平均年龄); (G)测量学校联结的工具(如PSSM, SCS等); (H)測量抑郁的工具(如CDI, CES等); (I)效应量(相关系数)。并且, 在编码时遵循以下原则: (1)若研究根据被试特征分别报告效应量, 则分别编码(如分开报告男性和女性的效应量); (2)每个独立样本进行一次编码, 若研究报告了多个独立样本, 则逐个编码; (3)若研究对多个变量指标进行测量, 则分别编码。随后, 将两位作者独立完成的编码表进行Kappa评分者信度检验以评估编码一致性。经计算, 两份编码表的Kappa系数为0.963, 一致性较高。最后, 由全体作者讨论后确定两份编码表中不一致的编码。

其次, 文献质量分析参照美国国立卫生研究院(National Institutes of Health, NIH)的纵向和横断研究质量评估工具(Quality Assessment Tool for Observational Cohort and Cross-Sectional Studies), 对纳入分析的研究依次评估, 并以符合标准(记1分)或不符合标准(记0分)进行计分(National Institutes of Health, 2014)。横断研究的评价总分介于0~8之间, 纵向研究的评价总分介于0~14之间。研究质量评分结果见网络版附录A, 评分越高表明文献质量越好。

2.3 效应量计算

本研究依次从纳入分析的研究中提取学校联结与抑郁的相关系数。由于相关系数不符合正态分布, 本研究在计算主效应或调节效应时将所有相关系数转为Fishers z分数(Cooper et al., 2019)。数据分析后, 再将Fishers z分数转为相关系数以便解释。本研究在解释相关系数大小时, 依照Cohen (1992)的标准, 以0.10、0.30和0.50为临界值, 分别判定小、中和大的效应量。

2.4 模型选择

本研究所纳入元分析的大多数原始文献报告了多个效应量。同一研究中报告的多个效应量往往来自同一样本, 因此效应量之间是相关的。值得注意的是, 传统元分析方法假设各效应量之间相互独立, 在一项研究中只提取一个效应量(Assink & Wibbelink, 2016)。这种元分析方法忽略了这种相关, 可能会导致总体效应量被高估(Lipsey & Wilson, 2001)。相较于传统元分析方法, 三水平元分析模型考虑了同一研究中效应量的依赖性, 将效应量的方差来源进一步分解为三个水平。水平1是纳入分析的原始研究在抽取样本时由抽样方法引起的误差。水平2源于同一研究所报告的多个效应量之间的差异, 若显著, 则表明同一研究的不同效应量具有异质性; 水平3源于不同研究所报告的效应量之间的差异, 若显著, 则表明不同研究的效应量具有异质性(Cheung, 2014)。因此, 相较于传统的元分析方法, 三水平元分析方法能够处理来自同一研究效应量之间的依赖性问题, 从而最大化地保留信息, 提高统计检验力(Assink & Wibbelink, 2016)。基于上述原因, 本研究将使用三水平元分析模型进行主效应检验、异质性检验、调节效应检验、发表偏倚检验以及敏感性分析。

2.5 异质性检验与调节效应检验

本研究将使用单侧对数似然比检验(one tailed log likelihood ratio tests)对水平2方差和水平3的方差进行分析, 以确定其是否显著, 若显著, 则可以进一步进行调节效应检验, 以确定异质性的来源(Gao et al., 2023)。本研究将调节变量作为协变量加入三水平元分析模型, 以估计其调节效应大小(Gao et al., 2023)。本研究的调节变量涉及: (1)连续调节变量: 样本中女性被试数占总被试数的比例、样本的平均年龄、发表年份。(2)分类调节变量: 学校联结的测量工具、抑郁的测量工具、研究数据属性、文化类型。本研究根据Card (2012)的建议设置调节变量水平, 各水平的效应量个数不少于5, 以此保证调节效应结果的代表性。

2.6 发表偏倚控制与检验

发表偏倚是指具有统计学意义的研究结果更容易发表(Franco et al., 2014)。发表偏倚是客观存在的, 因此研究者常常采用多种方法检验(Reed et al., 2015)。本研究将分别使用漏斗图(funnel plot)、Egger-MLMA回归法和剪补法对发表偏倚进行定性和定量评估。定性评估时, 若漏斗图呈对称的倒漏斗状, 则表明发表偏倚较小(Sterne & Harbord, 2004)。在纳入分析的效应量间非相互独立时, 与传统Egger回归法相比, Egger-MLMA回归法更能有效控制I类错误(Rodgers & Pustejovsky, 2021)。鉴于纳入分析的研究大多报告了彼此相关的多个效应量, 本研究选用Egger-MLMA回归法。若Egger-MLMA回归结果不显著, 则表明发表偏倚较小(Rodgers & Pustejovsky, 2021)。当Egger-MLMA回归显著(p < 0.05)或漏斗图呈现效应量不对称分布, 则采用剪补法检验出版偏倚给元分析结果造成的影响, 若剪补后的效应量未发生显著变化, 则可认为该元分析结果受发表偏倚影响较小(Duval&Tweedie, 2000)。

2.7 敏感性分析

纳入元分析的研究报告学校联结与抑郁的相关系数从?0.74到0.14, 结果差异大。这提示当前元分析结果存在受到异常值影响的风险, 可能导致虚假的统计结论(Kepes & Thomas, 2018)。为评估本元分析结果的稳健性, 本研究采用“去一法” (leave-one-out method)和三水平Cook距离法(Cooks distances method)剔除对元分析结果可能产生显著影响的异常值, 并重新进行三水平元分析以衡量异常效应量和异常研究的影响(Viechtbauer & Cheung, 2010)。“去一法”的具体步骤为, 逐个剔除纳入的效应量和原始研究, 并重新进行三水平元分析, 直到所有的效应量和原始研究均被剔除过(Dodell-Feder & Tamir, 2018)。Cook距离法的具体步骤为剔除Cook距离大于4/(n ? k ? 1)的效应量和原始研究并分别重新进行三水平元分析(Fox., 2019)。

2.8 数据处理

本研究使用R 4.2.0的metafor包进行元分析(Viechtbauer, 2010)。R代码来自Assink和Wibbelink (2016)以及Rodgers和Pustejovsky (2021)所发表的程序。本研究所有模型参数将采用限制性极大似然法(restricted maximum likelihood method)进行估计(Viechtbauer, 2010), 将双尾p值小于0.05的结果界定为显著。本研究数据处理过程中所使用到的公式见网络版附录C。

3 研究结果

3.1 文献纳入与质量评价

本研究共纳入研究87项(含87个独立样本, 206个效应值, 177828名被试), 时间跨度为1999~2023年。纳入文献的基本信息见表1。纳入的61项横断研究的文献质量评价得分范围在5分至8分, 均值为6.46分, 高于理论均值(4分); 纳入的26项纵向研究的文献质量评价得分范围在7分至12分, 均值为10.23分, 高于理论均值(7分)。整体而言, 纳入的文献质量较好。

3.2 主效应和异质性检验

当前元分析采用三水平元分析模型对学校联结与抑郁的关系进行主效应估计。结果显示, 学校联结与抑郁之间呈显著负相关(r = ?0.39, df = 205, p < 0.001), 95% CI [?0.41, ?0.34]。基于Cohen (1992)的标准, 该相关系数属于中效应量。

研究内方差(水平2)和研究间方差(水平3)的显著性采用单侧对数似然比检验法确定。结果显示, 研究内方差(水平2) (σ2 = 0.01, p < 0.001)和研究间方差(水平3) (σ2 = 0.02, p < 0.001)均存在显著差异。在总方差来源中, 抽样方差(水平1)为1.86%, 研究内方差(水平2)为31.41%, 研究间方差(水平3)为66.73%。因此, 可以分析调节变量以进一步解释学校联结与抑郁的关系。

3.3 发表偏倚和敏感性检验

Egger-MLMA回歸的结果显著(t = ?2.41, df = 204, p = 0.02), Egger-MLMA回归的截距为?1.27, 95% CI [?2.31, ?0.23]。漏斗图(图2)显示, 实际观测的效应量呈不对称分布, 为使漏斗图呈对称分布, 需要剪补55个效应量在漏斗图右侧。剪补55个效应量后重新进行三水平元分析, 结果显示学校联结与抑郁的主效应量(r = ?0.20, p < 0.001)小于剪补前的效应量(r = ?0.39), 但显著性保持不变。

采用去一法逐个剔除纳入的效应量并重新进行三水平元分析, 结果显示, 剔除了Midgett和Doumas (2019)报告的一个相关系数后, 学校联结与抑郁的相关程度最低(r = ?0.39, df = 204, p < 0.001); 剔除了Datu等人(2023)报告的一个相关系数后, 学校联结与抑郁的相关程度最高(r = ?0.40, df = 204, p < 0.001)。逐个剔除纳入的原始研究并重新进行三水平元分析, 结果显示, 剔除了Datu等人(2023)报告的所有相关系数后, 学校联结与抑郁的相关程度最高(r = ?0.40, df = 204, p < 0.001); 剔除了Parr等人(2020)报告的所有相关系数后, 学校联结与抑郁的相关程度最低(r = ?0.39, df = 203, p < 0.001)。无论逐个剔除纳入的效应量, 还是逐个剔除纳入原始研究进行敏感性分析, 结果发现, 剔除前与剔除后重新计算的主效应在显著性上一致, 且都属于中等强度的相关。

采用三水平Cook距离法对效应量进行影响性分析的结果显示:存在10个效应值量可能对本元分析结果产生显著异常影响。剔除上述效应量后, 重新进行三水平元分析, 结果显示学校联结与抑郁的相关程度为r = ?0.37, 且研究内方差(水平2) (σ2 = 0.01, p < 0.001)和研究间方差(水平3) (σ2 = 0.01, p < 0.001)均存在显著差异。采用三水平Cook距离法对纳入的研究进行影响性分析的结果显示:存在4项原始研究可能对本元分析结果产生显著异常影响。剔除上述4项研究后, 重新进行三水平元分析。结果显示学校联结与抑郁的相关程度为r = ?0.38, 且研究内方差(水平2) (σ2 = 0.01, p < 0.001)和研究间方差(水平3) (σ2 = 0.02, p < 0.001)均存在显著差异。无论剔除异常效应值还是剔除异常研究, 结果均发现, 剔除前与剔除后重新计算的主效应在显著性上一致, 且都属于中等强度的相关。综上所述, 从敏感性分析看, 当前元分析结果受异常值影响小, 较为稳健可靠。

3.4 调节效应检验

利用元回归分析检验调节变量对学校联结与抑郁的关系是否存在显著影响, 结果如表2所示。女性比例的调节效应显著, F (1, 197) = 4.84, p = 0.03, 学校联结与抑郁的负相关随女性比例的增大而增大(β = ?0.00, p = 0.03)。研究数据属性的调节效应显著, F (1, 204) = 58.75, p < 0.001, 与纵向数据(r = ?0.27)相比, 在横断数据(r = ?0.42)下学校联结与抑郁的相关程度更大。抑郁测量工具的调节效应显著, F (4, 137) = 6.83, p < 0.001。在纳入分析的研究中, 使用CDI量表测得的抑郁与学校联结的相关程度最大(r = ?0.62); 使用OMDS量表测得的抑郁与学校联结的相关程度最小(r = ?0.15)。使用CDI量表的效应量显著大于使用CES-D的效应量(β = ?0.20, p < 0.001); 使用OMDS的效应量显著小于使用CES-D的效应量(β = 0.20, p < 0.05)。使用MFQ、RADS的效应量与使用CES-D的效应量没有显著差异。年龄的调节效应边缘显著, F (1, 175) = 3.83, p = 0.052, 学校联结与抑郁的负相关随年龄的增大而减小(β = 0.01, p = 0.052)。此外, 没有发现其他显著的调节效应。

4 讨论

4.1 学校联结与抑郁的关系

尽管目前不少理论与实证研究已经探讨了学校联结与抑郁的关系, 但结果并不一致。研究间的分歧提示有必要整合既往结果, 以更宏观的角度得出更确切的结论。本研究通过三水平元分析技术整合学校联结与抑郁的相关研究。主效应结果显示, 学校联结与抑郁存在中等强度的显著负相关。这与本研究的假设一致, 随着学校联结的增强, 个体的抑郁水平降低。该结果为两者关系做出了阶段性定论, 表明学校联结是个体抑郁的重要保护因素, 支持社会控制理论、社会计量器理论和自我决定理论的观点。需要注意的是, 漏斗图和Egger-MLMA回归的结果表明, 本研究可能受到发表偏倚的影响。剪补法检验结果表明主效应可能存在高估的倾向。

此外, 本研究元分析主效應在研究内(水平2)和研究间(水平3)的方差均显著, 该结果说明主效应存在异质性。这提示在探讨学校联结与抑郁的关系时不得孤立看待主效应的结果(Harrer et al., 2021)。抑郁的产生是各种因素的累积而不是单一因素的作用(Wright & Masten, 2005), 学校联结对抑郁的保护作用可能受其他因素影响而增强或减弱。因此, 需要进一步分析学校联结与抑郁关系的潜在调节变量, 以解释主效应的异质性, 从而更加全面地阐述两者关系。

4.2 学校联结与抑郁关系的调节变量

调节效应检验结果显示, 性别显著调节学校联结与抑郁的关系, 随着女性样本比例的增加, 学校联结与抑郁的负相关强度显著增加。该结果表明, 相较于男性, 学校联结对女性的抑郁影响更大, 支持本研究假设。在社会化过程中, 女性往往倾向于将自己定义为关系的一部分; 而男性则倾向于将自己定义为与关系相分离的个体(Davis et al., 2019; Yang et al., 2021)。相较于男性, 女性在学校中更倾向从教师和同学中寻求支持以应对压力产生的不良情绪反应(Yang et al., 2021)。因此, 相比男性, 学校联结对女性的抑郁有更强的保护作用。与此相一致, Allen等人的元分析(2018)发现, 相比男性, 女性报告更高水平的学校联结。

与本研究假设一致, 年龄对学校联结与抑郁关系有调节作用。具体表现为, 随着样本平均年龄的增长, 学校联结与抑郁的负相关强度减小。这表明, 学校联结对抑郁的影响随年龄增长而减弱。随着年龄增加, 来自学校的压力增强, 这可能削弱个体的学校联结水平, 导致学校联结对个体的抑郁保护作用降低(Henrich et al., 2005; Xu & Fang, 2021)。这与Rose等人(2022)的发现一致, Rose等人的研究表明学校联结对心理健康的保护作用随年龄增长而减弱。该结果一定程度上符合社会支持源一致理论, 当引发抑郁的压力因素和减少抑郁的保护因素同源于学校时, 其保护作用将随压力的增强而减少。这可能因为, 学校联结会促使学生不断适应来自学校重要他人的期待, 当来自学校的压力增强时, 高学校联结个体更可能抑制表达由压力引发的抑郁情绪, 这不仅无法降低抑郁水平, 甚至导致抑郁情绪的累积(Datu et al., 2022)。然而, 本研究并没有直接检验来自学校的压力在学校联结与抑郁关系中的作用, 未来需要更多研究对此问题做深入剖析。

与本研究的假设一致, 抑郁的测量工具显著调节学校联结与抑郁的关系。该结果表明, 不同测量工具测得的抑郁与学校联结的相关程度不一致, 使用CDI量表测得的效应值最大, 使用OMDS量表测得的效应值最小。这可能因为, CDI测量的是儿童的悲伤、孤独感、自我形象和社会适应(Sitarenios & Kovacs, 1999), 项目数较多, 较为全面, 是目前针对儿童青少年抑郁使用最广泛的自评量表(柳之啸 等, 2019)。而OMDS量表测量的是个体过去30天的抑郁情绪和抑郁行为(Orpinas, 1993), 项目数较少, 可能无法全面地衡量个体抑郁。本研究的结果和Fried (2017)的研究结果一致。Fried的研究发现采用不同抑郁量表所测的抑郁结果不尽相同。值得注意的是, 本研究发现学校联结的测量工具不调节学校联结与抑郁的关系。可能的原因是尽管学校联结不同的测量工具在内容和项目数量上均存在差异, 但是它们都涵盖了学校联结的主要内容, 具有趋同性。因此, 学校联结与抑郁的关系在不同学校联结测量工具下的结果相近。

本研究发现研究数据属性调节学校联结与抑郁的关系, 具体而言, 与纵向数据相比, 横断数据下的两者关系强度更大, 支持了本研究假设。随时间推移, 影响抑郁的因素增多(Goering & Mrug, 2022), 这导致学校联结与抑郁的相关减弱。这提示单一时间测量的横断数据容易夸大变量间的相关性, 未来应在不同时间点收集学校联结与抑郁的数据, 以此把握两者的动态趋势和发展规律。

与本研究假设不一致的是, 文化不调节学校联结与抑郁的关系。对此有两种可能的解释:一是无论在西方文化还是在中国文化下, 学校联结均是抑郁的一个重要保护因素。虽然中国的集体主义文化强调人的互依性、西方的个人主义文化强调人的独立性(黄梓航 等, 2018; Hofstede, 1980), 但它们对抑郁的总体效果是一致的。二是西方文化和中国文化的效应值有差异。然而, 当前元分析中基于中国文化的效应值较少(仅占15.27%), 效应值分布不均衡可能影响了调节效应的检出。学校联结与抑郁关系的文化差异还需更多跨文化研究来对此问题做深入剖析以验证本研究结果的可靠性。

同时, 与本研究假设不一致, 发表年份不调节学校联结与抑郁的关系。该结果与Allen等人(2018)的元分析结果一致。Allen等人通过元分析发现中学生的学校联结与心理健康的关系不随发表年份变化。这或许表明学校联结与抑郁的关系强度不随时代变迁和社会发展而变化。另一个可能的解释是, 虽然随时代发展, 来自学校的压力增加(俞国良, 王浩, 2020), 学校联结对个体抑郁的保护作用可能随之减弱; 但与此同时, 一些心理健康的保护因素(例如. 积极的父母教养方式)也在随着时代发展, 能更有效地缓解学校压力(Sari & Sulistiyaningsih, 2023; Liu & Rahman, 2022), 这或许在一定程度上抵消了学校压力对学校联结与抑郁关系造成的影响。当然, 这一假设仍有待进一步检验。在纳入的原始研究中, 报告数据收集年份的效应值太少, 这限制了本研究对时代指标的选取。值得注意的是, 仅采用论文发表年份作为时代的指标不仅过于简单(辛自强 等, 2013), 而且会低估数据收集的时效性(Oliver & Hyde, 1993)。未来研究需要选取更多的指标(例如. 数据收集年份)进一步考察时代的影响。

4.3 研究意义

本研究使用三水平元分析技术整合了国内外学校联结与抑郁关系的量化研究, 探讨了学校联结与抑郁的关系及其调节变量。本研究的理论和实践意义如下: 第一, 本研究发现年龄、性别调节学校联结与抑郁的关系, 但发表年份和中西方文化类型不调节两者的关系。该结果表明学校联结对抑郁的保护作用受到个体特征的影响, 且在不同时代和文化下均具有一致性。这不仅为解释现有研究结果间的不一致提供了思路, 而且提示了在运用学校联结干预抑郁时, 应注意社会环境和个体的心理、生理特征。第二, 本研究发现, 研究数据属性和抑郁测量工具会影响两者关系强度。这提示在评估学校联结与抑郁的关系时要考虑数据收集的时间间隔和抑郁量表的选择。第三, 本研究不仅发现学校联结与抑郁在主效应上存在中等程度的负相关, 同时在发表偏倚检验中剪补了55个学校联结与抑郁的正相关。这提示了学校联结对抑郁可能存在“双刃剑”效应, 在运用学校联结预防和干预抑郁时需要考虑不同情境。未来在促进学校联结来预防和干预抑郁问题时, 不仅需要关注学校联结程度的提高, 还需注意个体差异并降低来自学校的压力, 以此更恰当地运用学校联结来预防和干预个体抑郁。

4.4 不足与展望

本研究可能存在以下不足之处, 有待未来研究进一步完善。第一, 本研究纳入分析的大多数原始文献采用自我报告法测量学校联结和抑郁, 这可能会导致共同方法偏差; 并且, 被试自我报告的准确性可能会受到记忆效果、掩饰等因素的影响。因此, 为了有效减少共同方法偏差, 提高分析结果的可靠性, 未来可以结合自我报告、他人报告、生理测验等工具开展进一步研究以验证本研究的结果。第二, 学校联结包含学校归属(school belonging)、对学校重要性的态度(attitudes about school importance)和社会隶属(social af?liation)三个维度(Marraccini & Brier, 2017)。已有研究发现, 学校联结的维度调节学校联结与心理健康的关系(Rose et al., 2022), 学校联结不同维度与抑郁关系的差异也可能是造成异质性的原因。但由于本研究纳入分析的大多原始文献只报告了学校联结总分与抑郁的关系, 因此未能探讨学校联结的不同维度对抑郁的影响。未来研究可以关注不同维度的学校联结与抑郁的关系, 更全面的探讨学校联结对抑郁的影响。第三, 已有研究表明两者之间可能存在双向影响的关系(Davis et al., 2019; Klinck et al., 2020)。本研究只能推论出学校联结和抑郁存在相关关系, 无法揭示两者关系的方向。因此未来可以使用交叉滞后分析对两者关系的方向进行探讨。第四, 已有研究發现, 种族(Eugene et al., 2021)、学生的希望感(Gerard & Booth, 2015)、学业志向(Gerard & Booth, 2015)可能调节二者关系, 但是本研究纳入元分析的大部分文献没有报告研究对象的这些信息, 因此无法进行调节效应分析。未来元分析研究在考察学校联结与抑郁的关系时可以进一步探讨这些调节变量, 进而更好地归纳学校联结影响抑郁的条件。

5 结论

本研究通过三水平元分析技术发现, 学校联结与抑郁存在显著负相关, 学校联结程度越高, 个体抑郁水平越低。学校联结与抑郁的关系受到性别的调节, 相比男性, 女性的抑郁水平受学校联结的影响更大。学校联结与抑郁的关系受到年龄的调节, 学校联结与抑郁的负相关随年龄的增长而减小。抑郁测量工具和研究数据属性均能调节学校联结与抑郁的关系; 发表年份、文化类型、学校联结测量工具对学校联结与抑郁关系的调节不显著。

参考文献

*元分析用到的参考文献

*阿依孜巴·艾拜都拉. (2020). 中学生同伴依恋对抑郁的影响: 自尊和学校归属感的多重中介作用 (硕士学位论文). 新疆师范大学, 乌鲁木齐.

陈春花, 苏涛, 王杏珊. (2016). 中国情境下变革型领导与绩效关系的Meta分析. 管理学报, 13(8), 1174?1183.

*陈小莉. (2019). 高中生学校归属感与抑郁, 焦虑的关系研究——心理弹性的中介作用 (硕士学位论文). 华中师范大学, 武汉.

*杜渐, 杨秋莉, 杜丽红, 杨邻, 张杰, 孔军辉. (2012). 中医学生学校归属感与心理健康的关系. 中医教育, 31(4), 15?18.

*方敏. (2020). 高年级小学生综合活力对抑郁情绪的影响: 学校归属感的中介作用 (硕士学位论文). 湖南师范大学, 长沙.

黄梓航, 敬一鸣, 喻丰, 古若雷, 周欣悦, 张建新, 蔡华俭. (2018). 个人主义上升, 集体主义式微? ——全球文化变迁与民众心理变化. 心理科学进展, 26(11), 2068?2080.

柳之啸, 李京, 王玉, 苗淼, 钟杰. (2019). 中文版儿童抑郁量表的结构验证及测量等值. 中国临床心理学杂志, 27(6), 1172?1176.

*孙亚东. (2022). 农村青少年网络成瘾类别及其与抑郁和问题行为的关系: 学校联结的中介作用 (硕士学位论文). 西南大学, 重庆.

*覃小琼. (2020). 同伴侵害与中学生抑郁: 父母支持和联结的链式中介作用 (硕士学位论文). 皖南医学院, 芜湖.

*覃小琼, 李秀. (2022). 网络受欺负与青少年抑郁: 孤独感与学校联结的作用. 教育生物学杂志, 10(6), 473?478.

*温丽影, 朱丽君, 刘传, 苏姗姗, 金岳龙, 常微微. (2023). 安徽省某医学院校在校大学生专业认同和学校归属感与心理健康的关系. 沈阳医学院学报, 25(1), 58?64.

辛自强, 张梅, 何琳. (2012). 大学生心理健康变迁的横断历史研究. 心理学报, 44(5), 664?679.

*邢强, 梁俏, 李佳佳, 唐辉, 莫绮云. (2023). 学业鼓励对初中生抑郁的影响: 学校联结的中介作用和坚毅的调节作用. 广东第二师范学院学报, 43(3), 85?97.

殷颢文, 贾林祥. (2014). 学校联结的研究现状与发展趋势. 心理科学, 37(5), 1180?1184.

俞国良, 王浩. (2020). 文化潮流与社会转型: 影响我国青少年心理健康状况的重要因素以及现实策略. 西南民族大学学报(人文社科版), 41(9), 213?219.

张建平, 秦传燕, 刘善仕. (2020). 寻求反馈能改善绩效吗? ——反馈寻求行为与个体绩效关系的元分析. 心理科学进展, 28(4), 549?565.

*赵姒. (2022). 情感虐待对留守高中生抑郁的影响: 冗思的中介与学校联结的调节作用 (硕士学位论文). 信阳师范学院.

*赵子薇. (2022). 父母心理攻击对初中生抑郁情绪的影响: 自尊和学校联结的作用 (硕士学位论文). 山西大学, 太原.

周文洁. (2013). 高中生情绪表达性的个体差异研究. 中国民康医学, 25(19), 67?69 + 86.

Allen, K., Kern, M. L., Vella-Brodrick, D., Hattie, J., & Waters, L. (2018). What schools need to know about fostering school belonging: A meta-analysis. Educational Psychology Review, 30, 1?34.

*Anderman, E. M. (2002). School effects on psychological outcomes during adolescence. Journal of Educational Psychology, 94(4), 795?809.

*Arango, A., Clark, M., & King, C. A. (2022). Predicting the severity of peer victimization and bullying perpetration among youth with interpersonal problems: A 6-month prospective study. Journal of Adolescence, 94(1), 57?68.

*Arango, A., Cole-Lewis, Y., Lindsay, R., Yeguez, C. E., Clark, M., & King, C. (2019). The protective role of connectedness on depression and suicidal ideation among bully victimized youth. Journal of Clinical Child & Adolescent Psychology, 48(5), 728?739.

Assink, M., & Wibbelink, C. J. (2016). Fitting three-level meta-analytic models in R: A step-by-step tutorial. The Quantitative Methods for Psychology, 12(3), 154?174.

Bakan, D. (1966). The duality of human existence. Chicago, IL: Rand McNally.

Barbee, A. P., Cunningham, M. R., Winstead, B. A., Derlega, V. J., Gulley, M. R., Yankeelov, P. A., & Drue, P. B. (1993). Effects of gender role expectations on the social support process. Journal of Social Issues, 49(3), 175?190.

*Baker, A. C., Wallander, J. L., Elliott, M. N., & Schuster, M. A. (2023). Non-suicidal self-injury among adolescents: A structural model with socioecological connectedness, bullying victimization, and depression. Child Psychiatry & Human Development, 54(4), 1190?1208.

*Bakhtiari, F., Boyle, A. E., & Benner, A. D. (2020). Pathways linking school-based ethnic discrimination to Latino/a adolescents marijuana approval and use. Journal of Immigrant and Minority Health, 22, 1273?1280.

Baumeister, R. F., & Leary, M. R. (1995). The need to belong: Desire for interpersonal attachments as a fundamental human motivation. Psychological Bulletin, 117(3), 497? 529.

*Bouchard, M., Denault, A. S., & Guay, F. (2022). Extracurricular activities and adjustment among students at disadvantaged high schools: The mediating role of peer relatedness and school belonging. Journal of Adolescence, 95(3), 1?15.

*Burns, J. R., & Rapee, R. M. (2019). School‐based assessment of mental health risk in children: The preliminary development of the Child RADAR. Child and Adolescent Mental Health, 24(1), 66?75.

Card, N. A. (Ed). (2012). Applied meta-analysis for social science research. New York: Guilford Press.

Chen, X., Chang, L., & He, Y. (2003). The peer group as a context: Mediating and moderating effects on relations between academic achievement and social functioning in Chinese children. Child Development, 74(3), 710?727.

Cheung, M. W.-L. (2014). Modeling dependent effect sizes with three-level meta-analyses: A structural equation modeling approach. Psychological Methods, 19(2), 211? 229.

*Choi, J. K., Ryu, J. H., & Yang, Z. (2021). Validation of the engagement, perseverance, optimism, connectedness, and happiness measure in adolescents from multistressed families: Using first-and second-order confirmatory factor analysis models. Journal of Psychoeducational Assessment, 39(4), 494?507.

*Choi, M. J., Hong, J. S., Travis Jr, R., & Kim, J. (2023). Effects of school environment on depression among Black and White adolescents. Journal of Community Psychology, 51(3), 1181?1200.

Cohen, J. (1992). Quantitative methods in psychology: A power primer. Psychological Bulletin, 112(1), 155?159.

*Cole-Lewis, Y. C., Gipson, P. Y., Opperman, K. J., Arango, A., & King, C. A. (2016). Protective role of religious involvement against depression and suicidal ideation among youth with interpersonal problems. Journal of Religion and Health, 55, 1172?1188.

Cooper, H., Hedges, L. V., & Valentine, J. C. (2019). The handbook of research synthesis and meta-analysis. Russell Sage Foundation.

*Cupito, A. M., Stein, G. L., & Gonzalez, L. M. (2015). Familial cultural values, depressive symptoms, school belonging and grades in Latino adolescents: Does gender matter? Journal of Child and Family Studies, 24, 1638? 1649.

*Daley, S. C. (2019). School connectedness and mental health in college students. (Unpublished doctoral dissertation). Miami University, Oxford.

*Dansby Olufowote, R. A., Soloski, K. L., Gonzalez- Caste?eda, N., & Hayes, N. D. (2020). An accelerated latent class growth curve analysis of adolescent bonds and trajectories of depressive symptoms. Journal of Child and Family Studies, 29, 292?306.

*Datu, J. A. D., Mateo, N. J., & Natale, S. (2023). The mental health benefits of kindness-oriented schools: School kindness is associated with increased belongingness and well-being in Filipino high school students. Child Psychiatry & Human Development, 54(4), 1075?1084.

*Davis, J. P., Merrin, G. J., Ingram, K. M., Espelage, D. L., Valido, A., & El Sheikh, A. J. (2019). Examining pathways between bully victimization, depression, & school belonging among early adolescents. Journal of Child and Family Studies, 28, 2365?2378.

Dodell-Feder, D., & Tamir, D. I. (2018). Fiction reading has a small positive impact on social cognition: A meta- analysis. Journal of Experimental Psychology: General, 147(11), 1713?1727.

Duval, S., & Tweedie, R. (2000). Trim and fill: A simple funnel-plot?based method of testing and adjusting for publication bias in meta-analysis. Biometrics, 56(2), 455? 463.

*Ernestus, S. M., Prelow, H. M., Ramrattan, M. E., & Wilson, S. A. (2014). Self-system processes as a mediator of school connectedness and depressive symptomatology in African American and European American adolescents. School Mental Health, 6, 175?183.

*Eugene, D. R. (2021). Connectedness to family, school, and neighborhood and adolescents internalizing symptoms. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 18(23), 12602.

*Eugene, D. R., Crutchfield, J., & Robinson, E. D. (2021). An examination of peer victimization and internalizing problems through a racial equity lens: Does school connectedness matter? International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 18(3), 1085.

*Fernandez, A., Loukas, A., Golaszewski, N. M., Batanova, M., & Pasch, K. E. (2019). Adolescent adjustment problems mediate the association between racial discrimination and school connectedness. Journal of School Health, 89(12), 945?952.

*Forbes, M. K., Fitzpatrick, S., Magson, N. R., & Rapee, R. M. (2019). Depression, anxiety, and peer victimization: Bidirectional relationships and associated outcomes transitioning from childhood to adolescence. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 48, 692?702.

Fox, J. (2019). Regression diagnostics: An introduction. Sage publications.

Franco, A., Malhotra, N., & Simonovits, G. (2014). Publication bias in the social sciences: Unlocking the file drawer. Science, 345(6203), 1502?1505.

Fried, E. I. (2017). The 52 symptoms of major depression: Lack of content overlap among seven common depression scales. Journal of Affective Disorders, 208, 191?197.

Gao, S., Yu, D., Assink, M., Chan, K. L., Zhang, L., & Meng, X. (2023). The association between child maltreatment and pathological narcissism: A three-level meta-analytic review. Trauma, Violence, & Abuse, 25(1). https://doi.org/ 10.1177/15248380221147559

*Gerard, J. M., & Booth, M. Z. (2015). Family and school influences on adolescents' adjustment: The moderating role of youth hopefulness and aspirations for the future. Journal of Adolescence, 44, 1?16.

*Gilman, R., & Anderman, E. M. (2006). The relationship between relative levels of motivation and intrapersonal, interpersonal, and academic functioning among older adolescents. Journal of School Psychology, 44(5), 375? 391.

*Goering, M., & Mrug, S. (2022). The distinct roles of biological and perceived pubertal timing in delinquency and depressive symptoms from adolescence to adulthood. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 51(11), 2092?2113.

*Gonzalez, L. M., Stein, G. L., Kiang, L., & Cupito, A. M. (2014). The impact of discrimination and support on developmental competencies in Latino adolescents. Journal of Latina/o Psychology, 2(2), 79?91.

Goodenow, C. (1993). The psychological sense of school membership among adolescents: Scale development and educational correlates. Psychology in the Schools, 30, 79?90.

Goodenow, C., & Grady, K. E. (1993). The relationship of school belonging and friends values to academic motivation among urban adolescent students. The Journal of Experimental Education, 62, 60?71.

*Gummadam, P., Pittman, L. D., & Ioffe, M. (2016). School belonging, ethnic identity, and psychological adjustment among ethnic minority college students. The Journal of Experimental Education, 84(2), 289?306.

Harrer, M., Cuijpers, P., Furukawa, T.A., & Ebert, D.D. (2021). Doing meta-analysis with R: A hands-on guide (1st ed.). Chapman and Hall/CRC.

*Hatchel, T., Espelage, D. L., & Huang, Y. (2018). Sexual harassment victimization, school belonging, and depressive symptoms among LGBTQ adolescents: Temporal insights. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry, 88(4), 422?430.

*Hayre, R. S., Sierra Hernandez, C., Goulter, N., & Moretti, M. M. (2023, March). Attachment & school connectedness: Associations with substance use, depression, & suicidality among at-risk adolescents. Child & Youth Care Forum, https://doi.org/10.1007/s10566-023-09743-y

*He, G. H., Strodl, E., Chen, W. Q., Liu, F., Hayixibayi, A., & Hou, X. Y. (2019). Interpersonal conflict, school connectedness and depressive symptoms in Chinese adolescents: Moderation effect of gender and grade level. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 16(12), 2182.

Hedges, L. V., & Vevea, J. L. (1998). Fixed- and random- effects models in meta-analysis. Psychological Methods, 3, 486?504.

Henrich, C. C., Brookmeyer, K. A., & Shahar, G. (2005). Weapon violence in adolescence: Parent and school connectedness as protective factors. Journal of Adolescent Health, 37(4), 306?312.

Hirschi, T. (1996). Theory without ideas: Reply to Akers. Criminology, 34, 249.

Hofstede, G. (1980). Motivation, leadership, and organization: Do American theories apply abroad? Organizational Dynamics, 9(1), 42?63.

Hofstede, G. (1984). Cultural dimensions in management and planning. Asia Pacific Journal of Management, 1, 81?99.

*Hsieh, Y. P., Lu, W. H., & Yen, C. F. (2019). Psychosocial determinants of insomnia in adolescents: Roles of mental health, behavioral health, and social environment. Frontiers in Neuroscience, 13, 848.

*Jacobson, K. C., & Rowe, D. C. (1999). Genetic and environmental influences on the relationships between family connectedness, school connectedness, and adolescent depressed mood: Sex differences. Developmental Psychology, 35(4), 926.

*Jin, L., Hao, Z., Huang, J., Akram, H. R., Saeed, M. F., & Ma, H. (2021). Depression and anxiety symptoms are associated with problematic smartphone use under the COVID-19 epidemic: The mediation models. Children and Youth Services Review, 121, 105875.

*Joyce, H. D., & Early, T. J. (2014). The impact of school connectedness and teacher support on depressive symptoms in adolescents: A multilevel analysis. Children and Youth Services Review, 39, 101?107.

*Kaminski, J. W., Puddy, R. W., Hall, D. M., Cashman, S. Y., Crosby, A. E., & Ortega, L. A. (2010). The relative influence of different domains of social connectedness on self-directed violence in adolescence. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 39, 460?473.

*Kelly, A. B., OFlaherty, M., Toumbourou, J. W., Homel, R., Patton, G. C., White, A., & Williams, J. (2012). The influence of families on early adolescent school connectedness: Evidence that this association varies with adolescent involvement in peer drinking networks. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 40, 437?447.

Kepes, S., & Thomas, M. A. (2018). Assessing the robustness of meta-analytic results in information systems: Publication bias and outliers. European Journal of Information Systems, 27(9), 90?123.

*Kia-Keating, M., & Ellis, B. H. (2007). Belonging and connection to school in resettlement: Young refugees, school belonging, and psychosocial adjustment. Clinical Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 12(1), 29?43.

Kieling, C., Adewuya, A., Fisher, H. L., Karmacharya, R., Kohrt, B. A., Swartz, J. R., & Mondelli, V. (2019). Identifying depression early in adolescence. The Lancet Child & Adolescent Health, 3(4), 211?213.

*Klinck, M., Vannucci, A., & Ohannessian, C. M. (2020). Bidirectional relationships between school connectedness and internalizing symptoms during early adolescence. The Journal of Early Adolescence, 40(9), 1336?1368.

Korpershoek, H., Canrinus, E. T., Fokkens-Bruinsma, M., & de Boer, H. (2020). The relationships between school belonging and students motivational, social-emotional, behavioural, and academic outcomes in secondary education: A meta-analytic review. Research Papers in Education, 35(6), 641?680.

*Kuo, F. W., & Yang, S. C. (2019). In-group comparison is painful but meaningful: The moderator of classroom ethnic composition and the mediators of self-esteem and school belonging for upward comparisons. The Journal of Social Psychology, 159(5), 531?545.

*Lardier, D. T., Opara, I., Bergeson, C., Herrera, A., Garci- Reid, P., & Reid, R. J. (2019). A study of psychological sense of community as a mediator between supportive social systems, school belongingness, and outcome behaviors among urban high school students of color. Journal of Community Psychology, 47(5), 1131?1150.

*LaRusso, M. D., Romer, D., & Selman, R. L. (2008). Teachers as builders of respectful school climates: Implications for adolescent drug use norms and depressive symptoms in high school. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 37, 386?398.

*L?tsch, A. (2018). The interplay of emotional instability and socio-environmental aspects of schools during adolescence. European Journal of Educational Research, 7(2), 281?293.

Leary, M. R. (2005). Sociometer theory and the pursuit of relational value: Getting to the root of self-esteem. European Review of Social Psychology, 16(1), 75?111.

Lebow, J. L. (2005). Family therapy at the beginning of the twenty-first century. In J. Lebow (Ed.), Handbook of Clinical Family Therapy (pp. 1?14). Hoboken, New Jersey: John Wiley & Sons, Inc.

*Lee, J., Chun, J., Kim, J., Lee, J., & Lee, S. (2021). A social-ecological approach to understanding the relationship between cyberbullying victimization and suicidal ideation in South Korean adolescents: The moderating effect of school connectedness. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 18(20), 10623.

Libbey, H. P. (2004). Measuring student relationships to school: Attachment, bonding, connectedness, and engagement. Journal of School Health, 74, 274?283.

Lipsey, M. W., & Wilson, D. B. (2001). Practical meta-analysis. SAGE publications.

Liu, C., & Rahman, M. N. A. (2022). Relationships between parenting style and sibling conflicts: A meta-analysis. Frontiers in Psychology, 13, 936253.

*Liu, S., Wu, W., Zou, H., Chen, Y., Xu, L., Zhang, W., Yu, C & Zhen, S. (2023). Cyber victimization and non-suicidal self-injury among Chinese adolescents: The effect of depression and school connectedness. Frontiers in Public Health, 11, 1091959.

*Loukas, A., & Pasch, K. E. (2013). Does school connectedness buffer the impact of peer victimization on early adolescents subsequent adjustment problems? The Journal of Early Adolescence, 33(2), 245?266.

*Loukas, A., Suzuki, R., & Horton, K. D. (2006). Examining school connectedness as a mediator of school climate effects. Journal of Research on Adolescence, 16(3), 491? 502.

*Marksteiner, T., Janke, S., & Dickh?user, O. (2019). Effects of a brief psychological intervention on students' sense of belonging and educational outcomes: The role of students' migration and educational background. Journal of School Psychology, 75, 41?57.

Markus, H. R., & Kitayama, S. (2014). Culture and the self: Implications for cognition, emotion, and motivation. In college student development and academic life (pp. 264?293). Routledge.

Marraccini, M. E., & Brier, Z. M. (2017). School connectedness and suicidal thoughts and behaviors: A systematic meta-analysis. School Psychology Quarterly, 32(1), 5?21.

*Maurizi, L. K., Ceballo, R., Epstein‐Ngo, Q., & Cortina, K. S. (2013). Does neighborhood belonging matter? Examining school and neighborhood belonging as protective factors for Latino adolescents. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry, 83(2?3), 323?334.

*Mcgraw, K., Moore, S., Fuller, A., & Bates, G. (2008). Family, peer and school connectedness in final year secondary school students. Australian Psychologist, 43(1), 27?37.

*McLaren, S., Schurmann, J., & Jenkins, M. (2015). The relationships between sense of belonging to a community GLB youth group; school, teacher, and peer connectedness; and depressive symptoms: Testing of a path model. Journal of Homosexuality, 62(12), 1688?1702.

*McMahon, S. D., Parnes, A. L., Keys, C. B., & Viola, J. J. (2008). School belonging among low‐income urban youth with disabilities: Testing a theoretical model. Psychology in the Schools, 45(5), 387?401.

*Midgett, A., & Doumas, D. M. (2019). The impact of a brief bullying bystander intervention on depressive symptoms. Journal of Counseling & Development, 97(3), 270?280.

*Millings, A., Buck, R., Montgomery, A., Spears, M., & Stallard, P. (2012). School connectedness, peer attachment, and self-esteem as predictors of adolescent depression. Journal of Adolescence, 35(4), 1061?1067.

*Mrug, S., King, V., & Windle, M. (2016). Brief report: Explaining differences in depressive symptoms between African American and European American adolescents. Journal of Adolescence, 46, 25?29.

National Institutes of Health. (2014). Study quality assessment tools. Retrieved from: https://www.nhlbi.nih. gov/health-topics/study-quality-assessment-tools

Oelsner, J., Lippold, M. A., & Greenberg, M. T. (2011). Factors influencing the development of school bonding among middle school students. The Journal of Early Adolescence, 31(3), 463?487.

Oliver, M. B., & Hyde, J. S. (1993). Gender differences in sexuality: A meta-analysis. Psychological Bulletin, 114(1), 29?51.

Orpinas, P. (1993). Modified depression scale. Houston, TX: University of Texas Health Science Center at Houston.

Page, M. J., McKenzie, J.E., Bossuyt, P. M., Boutron, I., Hoffmann, T. C., Mulrow, C. D., … Moher, D. (2021). The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. International Journal of Surgery, 74(9), 790?799.

*Pang, Y. C. (2015). The relationship between perceived discrimination, economic pressure, depressive symptoms, and educational attainment of ethnic minority emerging adults: The moderating role of school connectedness during adolescence (Unpublished doctoral dissertation). Iowa State University, Ames.

Park, J., Kitayama, S., Karasawa, M., Curhan, K., Markus, H. R., Kawakami, N., ...

*Ream, G. L. (2006). Reciprocal effects between the perceived environment and heterosexual intercourse among adolescents. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 35, 768?782.

Reed, W. R., Florax, R. J. G. M., & Poot, J. (2015). A monte carlo analysis of alternative meta-analysis estimators in the presence of publication bias. Retrieved from http:// www.economics-ejournal.org/economics/discussionpapers/2015-9

Resnick, M. D., Bearman, P. S., Blum, R. W., Bauman, K. E., Harris, K. M., Jones, J., ... Udry, J. R. (1997). Protecting adolescents from harm: Findings from the National Longitudinal Study on Adolescent Health. The Journal of the American Medical Association, 278(10), 823?832.

Rodgers, M. A., & Pustejovsky, J. E. (2021). Evaluating meta-analytic methods to detect selective reporting in the presence of dependent effect sizes. Psychological Methods, 26(2), 141?160.

Rose, I. D., Lesesne, C. A., Sun, J., Johns, M. M., Zhang, X., & Hertz, M. (2022). The relationship of school connectedness to adolescents engagement in co-occurring health risks: A meta-analytic review. The Journal of School Nursing, 10598405221096802

*Ross, A. G., Shochet, I. M., & Bellair, R. (2010). The role of social skills and school connectedness in preadolescent depressive symptoms. Journal of Clinical Child & Adolescent Psychology, 39(2), 269?275.

Rueger, S. Y., Malecki, C. K., Pyun, Y., Aycock, C., & Coyle, S. (2016). A meta-analytic review of the association between perceived social support and depression in childhood and adolescence. Psychological Bulletin, 142(10), 1017.

Ryan, R. M., & Deci, E. L. (2017). Self-determination theory: Basic psychological needs in motivation, development, and wellness. Guilford Publications.

Sandler, I. (2001). Quality and ecology of adversity as common mechanisms of risk and resilience. American Journal of Community Psychology, 29(1), 19?61.

Sari, U. K., & Sulistiyaningsih, R. (2023). Parenting style to reduce academic stress in early childhood during the new normal. Indigenous: Jurnal Ilmiah Psikologi, 8(1), 82?93.

Sitarenios, G., & Kovacs, M. (1999). Use of the children's depression inventory. In M. E. Maruish (Ed.), The use of psychological testing for treatment planning and outcome assessment (pp. 267?298). Lawrence Erlbaum Associates Publishers.

*Shochet, I. M., Dadds, M. R., Ham, D., & Montague, R. (2006). School connectedness is an underemphasized parameter in adolescent mental health: Results of a community prediction study. Journal of Clinical Child & Adolescent Psychology, 35(2), 170?179.

*Shochet, I. M., Homel, R., Cockshaw, W. D., & Montgomery, D. T. (2008). How do school connectedness and attachment to parents interrelate in predicting adolescent depressive symptoms? Journal of Clinical Child & Adolescent Psychology, 37(3), 676?681.

*Shochet, I. M., Smith, C. L., Furlong, M. J., & Homel, R. (2011). A prospective study investigating the impact of school belonging factors on negative affect in adolescents. Journal of Clinical Child & Adolescent Psychology, 40(4), 586?595.

Sterne, J. A., & Harbord, R. M. (2004). Funnel plots in meta-analysis. The Stata Journal, 4(2), 127?141.

*Sun, R. C., & Hui, E. K. (2007). Psychosocial factors contributing to adolescent suicidal ideation. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 36, 775?786.

*Tang, T. C., Ko, C. H., Yen, J. Y., Lin, H. C., Liu, S. C., Huang, C. F., & Yen, C. F. (2009). Suicide and its association with individual, family, peer, and school factors in an adolescent population in southern Taiwan. Suicide and Life-Threatening Behavior, 39(1), 91?102.

Thapar, A., Collishaw, S., Pine, D. S., & Thapar, A. K. (2012). Depression in adolescence. The Lancet, 379(9820), 1056?1067.

*Thomson, K. C., Schonert-Reichl, K. A., & Oberle, E. (2015). Optimism in early adolescence: Relations to individual characteristics and ecological assets in families, schools, and neighborhoods. Journal of Happiness Studies, 16, 889?913.

*Thornton, B. E. (2020). The impact of internalized, anticipated, and structural stigma on psychological and school outcomes for high school students with learning disabilities: A pilot study. (Unpublished doctoral dissertation). University of California, Los Angeles.

*Truong, N. L., & Zongrone, A. D. (2022). The role of GSA participation, victimization based on sexual orientation, and race on psychosocial well‐being among LGBTQ secondary school students. Psychology in the Schools, 59(1), 181?207.

Vannucci, A., & McCauley Ohannessian, C. (2018). Self- competence and depressive symptom trajectories during adolescence. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 46, 1089?1109.

Viechtbauer, W. (2010). Conducting meta-analyses in R with the metafor package. Journal of Statistical Software, 36(3), 1?48.

Viechtbauer, W., & Cheung, M. W. L. (2010). Outlier and influence diagnostics for meta‐analysis. Research Synthesis Methods, 1(2), 112?125.

World Health Organization. (2023). Depression. Retrieved from https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/ depression.

*Wright, M. F., & Wachs, S. (2019). Adolescents psychological consequences and cyber victimization: The moderation of school-belongingness and ethnicity. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 16(14), 2493.

Wright, M. O. D., & Masten, A. S. (2005). Resilience processes in development: Fostering positive adaptation in the context of adversity. In S. Goldstein & R. B. Brooks (Eds.), Handbook of resilience in children (pp. 17?37). Kluwer Academic/Plenum Publishers.

*Wright, S. (2017). How does coping impact stress, anxiety, and the academic and psychosocial functioning of homeless students? (Unpublished doctoral dissertation). University of Arizona.

Xu, Z. Z., & Fang, C. C. (2021). The relationship between school bullying and subjective well-being: The mediating effect of school belonging. Frontiers in Psychology, 12, 725542.

Yang, L., Zheng, Y., & Chen, R. (2021). Who has a cushion? The interactive effect of social exclusion and gender on fixed savings. Journal of Consumer Affairs, 55(4), 1398? 1415.

*Yang, Y., Ma, X., Kelifa, M. O., Li, X., Chen, Z., & Wang, P. (2022). The relationship between childhood abuse and depression among adolescents: The mediating role of school connectedness and psychological resilience. Child Abuse & Neglect, 131, 105760.

*Zhai, B., Li, D., Li, X., Liu, Y., Zhang, J., Sun, W., & Wang, Y. (2020). Perceived school climate and problematic internet use among adolescents: Mediating roles of school belonging and depressive symptoms. Addictive Behaviors, 110, 106501.

*Zhang, M. X., Mou, N. L., Tong, K. K., & Wu, A. M. (2018). Investigation of the effects of purpose in life, grit, gratitude, and school belonging on mental distress among Chinese emerging adults. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 15(10), 2147.

*Zhang, Z., Wang, Y., & Zhao, J. (2022). Longitudinal relationships between interparental conflict and adolescent depression: Moderating effects of school connectedness. Child Psychiatry & Human Development, 1?10.

*Zhao, Y., & Zhao, G. (2015). Emotion regulation and depressive symptoms: Examining the mediation effects of school connectedness in Chinese late adolescents. Journal of Adolescence, 40, 14?23.

*Zhou, X., Min, C. J., Kim, A. Y., Lee, R. M., & Wang, C. (2022). Do cross-race friendships with majority and minority peers protect against the effects of discrimination on school belonging and depressive symptoms? International Journal of Intercultural Relations, 91, 242?251.

The relationship between school connectedness and depression:A three-level meta-analytic review

MENG Xianxin1, CHEN Yijing1, WANG Xinyi1, YUAN Jiajin2, YU Delin1

(1 School of Psychology, Fujian Normal University, Fuzhou 350117, China)(2 Sichuan Key Laboratory of Psychology and Behavior of Discipline Inspection and Supervision, Institute of Brain and Psychological Sciences, Sichuan Normal University, Chengdu 610066, China)

Abstract: Existing studies on the relationship between school connectedness and depression have produced inconsistent results. To clarify the extent to which school connectedness is associated with depression, and whether these associations differed according to the study or sample characteristics, a three-level meta-analysis of 87 included studies (206 effect sizes) was conducted. The results showed that there was a significant negative correlation between school connectedness and depression but only to a medium extent (r = ?0.39, df = 205, p < 0.001). Additionally, the relationship between school connectedness and depression was found to be moderated by the percentage of female students, mean age of participants, measurement of depression, and data characteristics. No significant moderating effects were found for the measurement of school connectedness, culture, or publication year. School connectedness is a protective factor for depression. Interventions targeting depression should be aware of school connectedness.

Keywords: school connectedness, depression, three-level meta-analysis, social control theory, sociometer theory, self-determination theory

附录C 数据分析中使用到的计算公式

使用Hedges和Vevea (1998)提出的公式将相关系数r转换为Fisher's z。

其中r是皮尔逊积差相关系数, zr是r的Fisher变换后的值。

主效应的标准误是其方差的平方根。

将zr转换回r。

其中e是指数函数, r是皮尔逊积差相关系数, zr是r的费舍尔变换。

使用三水平元分析模型估计学校联结和抑郁之间的关系的主效应大小。

Level 1 model: yij = λij + eij

Level 2 model: λij = κj + u (2)ij

Level 3 model: κj = β0 + u (3)j (Eq. 7)

其中, yij代表第j项研究中的一个独特的效应大小; λij是“真实”的效应大小; eij是第j项研究中第i个效应大小的已知抽样误差。κj是第j项研究的平均效应; β0是平均群体效应, Var (u (2)ij) =和Var (u (3)ij) =分别是研究特定的2级和3级异质性。

与两水平元分析模型类似, 上述等式通常被合并为:

yij = β0 + u (2)ij + u (3)j + eij (Eq. 8)

使用混合效应模型来研究(潜在的)调节变量对学校联结和抑郁之间关系的影响。有一个协变量的混合效应模型如下:

yij = β0 + β1Xij + u (2)ij + u (3)j + eij (Eq. 9)

其中X是协变量, 其他项的解释与Eq. 8类似, 只是和现在是控制协变量后的二水平和三水平残留异质性。