毕生发展视角下独处的适应功能:益处与代价的五轮比较

阿尔升·海达别克 周同 喻洁 王计悦意 陈飞 丁雪辰

摘 要 独处是一种在真实和虚拟环境中个体与他人没有交流的状态。从童年期到老年期, 独处在个体不同发展阶段带来不同的影响。关于独处的适应功能, 以往研究者持不同的观点, 或积极论或消极论, 且有一种观点认为: 独处同时具有益处与代价。鉴于研究者们对于独处的观点不一致, 本研究从毕生发展的视角出发, 对各个发展时期独处益处与代价的相关研究进行梳理, 探讨其动态变化与发展, 并提出了毕生发展视角下独处益处与代价的比较模型。未来研究可以更多关注以个体为中心的研究, 整合独处多维性, 以毕生发展视角收集横纵向数据直接对比, 丰富独处益处与代价的发展机制, 结合文化背景理解独处的内涵, 关注当代数字技术发展背景对于个体独处的影响, 考察独处的认知神经机制, 并思考独处在不同年龄段的实践意义。

关键词 独处, 毕生发展观, 适应功能, 益处, 代价

分类号 B844

1 引言

在过去, 研究者关注更多的是社会互动与人际关系对于个体发展的重要意义, 相对忽略了独处(solitude)的影响(陈晓, 周晖, 2012)。而事实上, 独处与社会互动同样普遍存在于人的一生之中, 且两者是同等重要的成长需求, 都可以用来解决矛盾、降低病态(Coplan, Hipson, et al., 2019), 每个有机体都需要在亲密与独处之间寻求平衡(陈晓, 周晖, 2012)。在成长的过程中, 个体会出于各种不同的原因体验独处, 并会在独处时主动做出一些行为, 从而产生不同的影响。有些人可能会将独处作为面对生活压力时给自己提供一个喘息的机会, 或安静地沉思, 或培养创造性, 或与大自然交流; 而另一些人则可能因被他人孤立而遭受着独处的痛苦(Coplan, Bowker, et al., 2021)。由此可见, 独处具有一定的复杂性。

针对这种复杂性, 不同研究者对独处做出了不同的界定。例如, 在较早时期, Burger (1995)认为, 独处是个体没有任何社会互动的状态, 而Larson (1990)则认为个体在意识上与他人分离, 信息或情感均无与外界交流的状态就是独处, 这种独处强调意识上的远离, 而不是物理上的远离。随后Long等人(2003)则提出, 独处是不论在真实还是虚拟环境, 均与他人无互动的客观状态。但随着时代的发展, 屏幕和其他形式数字技术无处不在的现实有可能完全重塑我们对独处的概念界定(Coplan et al., 2018), Campbell和Ross (2022)最近的文章指出: 数字时代下独处的界定应从“独自一人(being alone)”转变为“不交流(noncommunication)”。从上述定义中可以发现, 目前大多研究都将独处广泛定义为个体与外界缺乏互动或不交流的一种行为状态, 区别于孤独感(loneliness)只能体验到单一的消极情绪, 在本研究中我们认为独处是一种在真实和虚拟环境中个体与他人没有进行交流, 能够容纳不同情绪体验的状态。

适应是个体发展不可或缺的要素, 不仅能够反映个体发展的现状, 而且对其未来也有重要的价值。近年来, 研究者们一直不断探讨独处的适应功能(Hoppmann et al., 2021; Lay et al., 2019; Luo et al., 2022; Pauly et al., 2022), 并对此持有不同的观点: 一些研究表明独处可能伴随着孤独感等负面情绪(Hoppmann et al., 2021; Pauly et al., 2022), 另一些研究则认为独处可以是积极的体验(Lay et al., 2019), 还有研究者持独处是一把双刃剑, 它既有益处也同样有一定的代价(Lay et al., 2018)。鉴于目前对于独处适应功能的争议性, 本研究选取心理适应和社会适应等关键变量, 提出从毕生发展的视角探讨个体一生不同年龄阶段独处的益处与代价之间的比较, 以更好地理解独处动态变化与发展, 并对Coplan, Ooi等人(2019)的独处发展时间效应理论模型进行拓展, 从而发现个体独处因各年龄阶段发展任务的不同具有不同的适应功能, 更全面地解释独处对个体适应的意义所在。

2 第一轮: 童年期独处代价占据上风

对于童年早期儿童而言, 独处状态常被描述为独自游戏, 是一种十分常见的现象(Rubin, 1982)。研究者认为, 獨自游戏(如旁观行为、敲打积木、假装游戏、试图弄明白玩具操作原理等; Coplan et al., 2014)是学龄前儿童社会交往发展的重要条件(Katz & Buchholz, 1999)。例如, 沉默行为是大部分儿童在独自玩耍和他人玩耍之间发展出规范的桥梁, 儿童通过从观看他人玩耍(即旁观), 到与其他孩子一起玩耍(即平行玩耍), 再到社会参与(即群体游戏和同伴对话) (Rubin et al., 2002)。

然而, 童年期独处给儿童可能带来更多的是消极影响。偏好独处的儿童不仅易引发其不良思维模式(Long & Averill, 2003), 其社会能力的发展也受到抑制。例如, 研究发现选择独处的儿童会面临更多的同伴互动困难(Ding et al., 2015; Ding et al., 2019; Ladd et al., 2011; Nelson et al., 2008), 更多的行为抑制(Smith et al., 2019), 更多的内化问题行为(Coplan et al., 2013; Gornik et al., 2018), 以及更多的学校适应不良(Chen et al., 2011)。最近, 一项横向跨年龄对比的研究发现: 相比青少年时期, 儿童时期的独处偏好与社会情绪适应困难有着更强的联系(Ding et al., 2023)。这可能是由于从童年早期开始, 儿童与同伴互动的数量和质量都在逐步上升, 同伴互动逐渐成为儿童日常社交环境中的常态和规范(Rubin et al., 2018), 儿童的社会、情绪和认知发展及心理健康都需要大量的积极同伴互动作为保证(Rubin et al., 2015)。例如, 研究者发现当需要在擅长社交的同伴和经常单独游戏的同伴中做出玩伴选择时, 即使单独游戏的玩伴被描述为可爱的, 童年早期儿童仍会报告不想与其共同游戏(Coplan et al., 2007; Zava et al., 2019)。

综上, 在童年期, 虽然独自游戏为个体社交技能的发展提供了铺垫, 但在同伴互动发展的重要阶段, 独处却导致了儿童缺乏同伴交往的机会, 从而给个体的社会情绪适应带来负面影响。因此在这一年龄阶段, 独处的代价占据上风。

3 第二輪: 青少年期独处代价达到顶峰

青少年期被认为是独处重要而又独特的发展时期(Bowker et al., 2016)。“金发姑娘假说(Goldilocks Hypothesis)”认为青少年有一个“刚刚好”的独处频率, 独处过长过短都可能是有问题的(Coplan, Hipson, et al., 2021), 独处时间过长不利于建立和维持同伴关系(Coplan, Ooi, et al., 2019), 独处时间不足会带来消极的情绪与感受(Yang et al., 2023)。在这一时期, 独处受到了格外多关注与探讨, 其适应功能也开始逐渐过渡与转型。Fromm-Reichmann (1959)从发展的角度提出“成长的独处” (growing aloneness)来描绘从青春期开始的独处现象。例如, 美国一项研究对383名儿童进行从幼儿园时期至12年级为期13年的追踪, 发现随着年龄增长, 儿童独处偏好平均水平呈上升趋势, 与低年级相比, 青少年期独处偏好的增长速度有所加快(Ladd et al., 2019)。在中国背景下, Hu等人(2022)在13~16岁青少年中也发现了类似的增长轨迹。这一发展特征可能与青少年后期的心理适应相关(Coplan, Ooi, et al., 2019; Teppers et al., 2013), 偏好独处的儿童开始希望参与并享受单独活动时间(Borg & Willoughby, 2022; Coplan, Ooi et al., 2021), 对隐私的渴望也同步增加(Maes et al., 2016), 对独处产生更加积极的态度(Danneel et al., 2018; Wood et al., 2022), 这种建设性的独处可能会给青少年的发展带来积极影响(Corsano et al., 2019; Hipson et al., 2021; Thomas & Azmitia, 2019)。

但是, 这一年龄阶段个体独处的代价可能依然远高于其益处。考虑到同伴关系对于青少年发展的重要意义, 独处可能会限制青少年形成积极的同伴关系和学习关键社交技能的机会(Bowker et al., 2021)。无论是青少年早期、中期还是晚期, 独处都更明显地与消极适应结果相关联。例如, 许多研究均发现, 独处偏好与青少年早期的抑郁和低自尊等内化行为问题有关(Hu et al., 2022; Wang et al., 2013; Zhang & Eggum-Wilkens, 2018), 且不被同伴所接纳(Bowker & Raja, 2011; Liu et al., 2015)。Coplan和Ooi等人(2019)认为, 青春期早期和中期是独处最有可能与消极适应相关的年龄阶段。与此同时, 青春期后期的独处已被证实与焦虑、孤独和抑郁等消极情绪相关(Thomas & Azmitia, 2019), 并且也面临着同伴交往能力低下的问题(Rubin et al., 2015)。

青春期的独处具有其独特性, 随着青少年自主性的发展, 独处偏好也随之增加。“刚刚好的独处”和“成长性的独处”或许可以帮助青少年可以进行自我探索。但尽管如此, 青少年的独处仍易产生多种内化行为问题, 并且使青少年面临着社会适应不良的风险, 独处的代价在这一阶段持续上升达到顶峰。

4 第三轮: 成年早期独处益处逐步显现

Winnicott (1958)从客体关系理论的视角出发, 用“悖论” (paradox)一词来解释成年人独处能力形成源于婴儿期的安全依恋, 独处能力的形成使得成年早期个体对于独处的接受度越来越高(Bowker et al., 2020)。随着个体自主性的不断发展以及身份角色的转变, 成年早期个体寻求独处的意愿变得更强, 并期待通过“独自度过安静的时光”获得休息(Toyoshima & Sato, 2015)。近期有研究提出成年早期有两种独立的独处动机结构: 自我决定的独处和非自我决定的独处, 并发现自我决定的独处动机可以让个体在自我接纳和个人成长方面表现出更高的幸福感(Thomas & Azmitia, 2019), 显著增加了积极独处体验的机会(Larson, 1990; Long & Averill, 2003), 并缓解低归属感个体的孤独感(Nguyen et al., 2019), 与积极的适应结果有关(Tse et al., 2022)。与此同时, 对于主动选择独处的年轻人而言, 独处可以带来放松和压力减轻, 同时不被独处时的侵入式消极思维所困扰(Nguyen et al., 2018; Nguyen et al., 2022)。

尽管拥有独处能力被认为是成年早期的一种良性发展特征(Bowker et al., 2017; Coplan, Ooi, et al., 2019), 但也有研究发现成年早期个体的独处偏好与负面情绪之间存在正相关关系(Toyoshima & Sato, 2015)。究其原因, 可能是独处态度与独处动机的匹配度所致。例如, Zhou等人(2023)采用潜在剖面分析探讨中国大学生不同独处亚型, 发现在4类独处亚型中, 积极独处?动机驱动组表现出了最高水平的自主独处动机和最高水平的独处偏好, 并且适应良好。而消极独处组则表现出最高水平的厌恶独处态度和最低水平的自主独处动机。这样的结果提示, 当独处的态度(偏好vs.厌恶)与动机(自我决定vs. 非自我决定)方向一致时, 成年早期的独处偏好可能会给个体带来积极的发展结果(Zhou et al., 2023)。

成年早期独处的消极影响有所转变, 独处的代价不再占据绝对上风, 自我决定的独处动机有助于个体自我接纳, 独处的益处得以逐步显现。所以, 在这一阶段, 独处动机和态度仍是决定个体独处结果适应与否的关键因素, 两者的不一致可能会使个体产生适应不良的风险。

5 第四轮: 成年中期益处与代价不相上下

尽管研究者认为独处在整个成年期是普遍存在的体验, 甚至有时选择独处的时间会远超过和他人呆在一起的时间(Larson, 1990; Lay et al., 2020; Leary et al., 2003), 但与成年早期和老年期相比, 成年中期因其所处生命阶段的特定目标和社会角色, 承担着最重的养育照顾责任和生活压力(Mehta et al., 2020), 所以他们可能更少有时间或自由去独处(Larson, 1990; Lay et al., 2018)。与之对应的是, 成年中期的个体可能出于逃避现实等原因对于独处抱有很高的渴望(Ost mor et al., 2020), 相比于成年早期个体表现出更多的自主性独处动机和更多的独处偏好(Toyoshima & Sato, 2019; Weinstein et al., 2021)。他们的自我决定动机可能会随着独处能力的提高和更好的自我调节能力而蓬勃发展(Yuan & Grühn, 2022), 并已获得相关证据支持。例如, 两项基于成年早期至老年期个体的经验抽样研究发现, 年龄越大且自主性越高的个体对日常独处时刻的体验越积极(Nikitin et al., 2022)。成年中期个体寻求独处是通过把时间花在自己身上, 进行调节活动(如冥想), 将注意力引导到内在状态, 从而恢复能量(Korpela & Staats, 2021); 又或是在独处时进行更多的自我反省活动, 培养了更多的耐心和精神投入(Weinstein et al., 2021), 这些活动都可能会给个体发展带来长期的好处(Ardelt & Grunwald, 2018)。

另一方面, 成年中期的独处也同样暗含着潜在风险。最近一项在疫情期间开展的横向研究发现, 与青少年和老年人相比, 尽管成年中期个体的自主动机最强, 但是他们在独处时的情绪波动较多, 并认为独处时间破坏了自己的幸福感与对周围的熟悉感(Weinstein et al., 2021), 当然, 值得注意的是, 在疫情期间被试可能经历了非典型的独处状态, 破坏了社交时间和独处时间的平衡(Robb et al., 2020)。随着成年人所经历的特定阶段的生活目标、挑战、环境和需求的变化(Mehta et al., 2020), 个体从成年早期到成年中期, 独处偏好也会发生变化, 并且与其不同的情感状态相联系。研究发现, 较高的独处偏好水平与社会情绪水平表现出负相关, 如孤独感增加, 生活满意度降低, 积极情感减少(Burger, 1995; Lay et al., 2018; Toyoshima & Sato, 2019)。这同样与以往研究者关于“独处是一把双刃剑”的观点(Lay et al., 2018)相呼应。至于它是益处或是代价, 还是两者兼而有之, 取决于一个人对独处的动机与态度(Yuan & Grühn, 2022)。对此, 有研究发现, 对于喜欢独处的母亲而言, 积极独处有助于缓解养育压力对心理适应的影响; 而对于独处偏好较低的母亲, 非自愿独处则会加剧他们受到压力之后的消极心理, 降低婚姻满意度(Dong et al., 2022)。

在成年中期, 个体的身份有所转变, 面临沉重的养育责任和生活压力, 个体会对于独处有更高的需求与更高的自主动机, 以获得放松或调整自我。但在这一阶段独处仍会对个体的社会情绪适应产生消极影响, 此时独处益处和代价不相上下, 难以体现其差异。

6 第五轮: 老年期独处代价再次抬头

虽说独处贯穿于个体的一生之中, 但独处时间在老年时期是相对最长的, 甚至部分老年人生活中71%的时间处于独处状态(Chui et al., 2014; Pauly et al., 2018)。Diekema (1992)的社会关系视角(Aloneness and Social Form)认为, 每一种独处状态暗含个体与群体关系的独特意义, 对于社交网络冲突多的个体, 独处的负面影响较低(Birditt et al., 2018)。这样看来, 独处似乎是有益于老年期个体自身的, 那些表现出更多独处偏好的老年人, 同时也报告了更多积极的独处经历, 更少的孤独感, 更少的负面影响(Li & Tang, 2022; Nikitin et al., 2022; Toyoshima & Sato, 2015), 和对于独处更多的享受(Lay et al., 2020)。最近的一项研究(Toyoshima & Sato, 2019)通过比较青年、中年、老年三个年龄组个体的独处偏好, 得到关于老年人独处偏好更加直接的研究证据: 相比于其他组, 老年人同时报告了更多的独处时间以及更多的积极情绪。

与上述研究证据相对矛盾的是, 另一项针对18~84岁个体的研究采用了为期10天日記法的方式发现: 平均独处时间越长, 孤独感会越强烈, 并且这种关联在老年个体中更为突出(Pauly et al., 2022)。可见, 同样对于老年人来说, 独处依然同时包含了积极和消极的含义(Hoppmann et al., 2021), 并且不能简单认为老年期的独处偏好存在绝对的积极意义。个体社交网络成员的离世或退休带来的社会角色变化导致老年人客观上会经历更多的被迫性独处(Fiori et al., 2007; Wagner et al., 1999), 而这种被迫独处的代价也具有相当的危险性。例如, 老年人独自生活会存在因身体健康下降、残疾以及伴侣和朋友死亡等因素而面临的社会孤立风险(Courtin & Knapp, 2017; Victor & Bowling, 2012)。如果老年人因身体原因自主性需求没有被满足, 独处变为被迫的选择, 那么这种社交隔离也会引起适应不良(Hoppmann et al., 2021; Lang & Baltes, 1997), 如老年人抑郁风险增加、更低水平的生活满意度等(Golden et al., 2009; Toyoshima & Sato, 2015; Zunzunegui et al., 2003), 产生诸多消极影响。

整体而言, 相对于成年期其他阶段, 个体在老年期具有更多可支配的时间, 并且对于独处具有更高的自主性, 他们可以通过独处来调节情绪、从中享受独处。与此同时, 不可否认的是老年期个体更容易面临社会孤立而被迫独处, 这会给个体情感、生活、社交方面带来风险, 使得独处的代价再次抬头。

7 总结

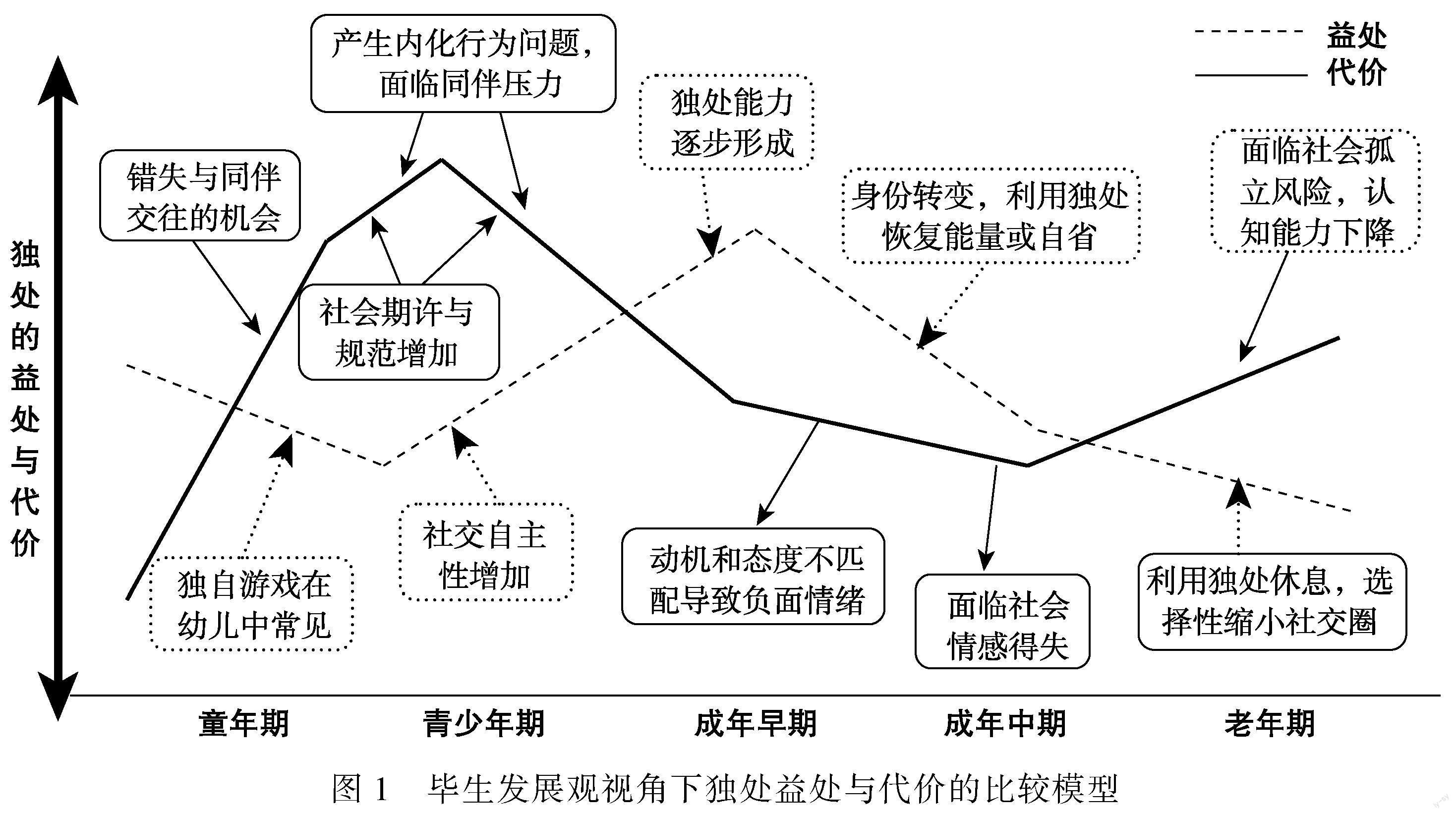

综上所述, 本研究以毕生发展的视角讨论个体从童年期到老年期独处的发展特点与适应功能, 揭示独处的确是一把双刃剑, 对于个体的发展同时具有益处与代价。总体而言, 不同年龄阶段个体独处表现出一定的变化特点, 如儿童时期的独自游戏→青少年期的自我探索与娱乐→成年早期的工作与休息→成年中期的放松与反省→老年期的问题解决与情绪调节。且随着年龄的发展, 不同阶段独处益处与代价的表现出不同的特征。在童年期, 儿童进行独自游戏是发展其社会交往功能的桥梁, 但与此同时这也直接导致个体错失与同伴交往的机会, 独处的代价占据上风; 在青少年期, 尽管个体有更大的社交自主性, 但其所面临社会期许与规范增加, 這时独处易产生多种内化行为问题且面临着同伴的压力, 独处的代价达到顶峰; 在成年早期, 自我决定的独处动机有助于自我接纳和个人成长, 独处的益处开始逐步显现, 但是因动机与态度的不一致, 个体可能也会产生一些负面情绪; 在成年中期, 随着个体身份转变, 对于独处有更高的需求和自主动机, 但也面临不同的社会情感得失, 此时独处的益处和代价不相上下; 到了老年期, 个体对于独处具有很高的自主性并且开始享受独处, 但是这一阶段老年人可能会面对社交孤立, 这会对个体认知、情感、生活带来极大的威胁, 独处的代价再次抬头。

最后, 本研究绘制了毕生发展视角下童年期至老年期独处益处与代价的比较模型(见图1)。

8 思考与展望

从毕生发展的视角探讨独处具有重要的理论与实践意义, 因为独处与人际交往并存于人生发展的每个阶段, 并对个体的发展带来或积极或消极的影响。尽管以往研究者关注到儿童及青少年独处的适应功能, 但对其理论解释以及发展轨迹仍存在以下一些不足, 需要在未来加以探索与改善。

8.1 以个体为中心的视角, 整合独处的多维性

虽然许多研究者已从不同角度关注了独处, 但目前的研究大多是以变量为中心对独处进行探讨, 鲜有研究将独处状态的多维特点同时进行考察。而以往研究提出观点认为: 独处是一种复杂而多维的状态(Coplan, Bowker et al., 2021), 因此这种整合对于理解独处这一复杂现象来说是十分必要的, 单独考察某一方面往往造成理解上的偏颇, 例如认为偏好独处就是适应不良而忽略了选择独处的动机。整合独处的多个维度能够更好地捕捉个体行为的潜在差异, 从不同的角度深入探究独处这一概念本身(Bowker et al., 2014)。目前仅有个别研究采用以个体为中心的研究方法, 试图整合独处的多个维度(Borg & Willoughby, 2023, M年龄 = 12.48岁; Hipson et al., 2021, 青少年, M年龄 = 16.14岁; Lay et al., 2018, 成人, M年龄 = 20 ~ 67岁; Maes et al., 2016, 青少年, M年龄 = 16.56 ~ 15.78岁; Zhou et al., 2023, 大学生, M年龄 = 19.71岁)。由于以个体为中心的研究方法对于变量指标的选择具有一定的灵活性, 目前这几项研究的结果并不能进行直接相互比较, 未来研究可以在不同发展阶段, 采用以个体为中心的研究方法(如潜在剖面分析等), 更加系统地整合考察独处的多维结构。

8.2 以毕生发展为视角, 直接检验独处适应功能的动态发展

从毕生发展的视角探索独处, 需要关注独处在不同发展阶段的独特功能。尽管Coplan和Ooi等人(2019)提出了独处的发展时间效应模型, 并且许多研究者都关注到了不同年龄阶段独处的适应功能(Zava et al., 2019, 儿童, M年龄 = 4.86岁; Hu et al., 2022, 青少年, M年龄 = 14.65岁; Nikitin et al., 2022, 年轻人和老年人, M年龄 = 19~88岁; Ost mor et al., 2020, 中年人, M年龄 = 41~60岁), 但目前独处的研究大多只限于儿童与青少年发展阶段, 成年期、老年期的研究稍显不足, 且大部分的研究证据较为分散, 难以直接整合进行比较。同时, 仅有少量研究尝试直接比较童年期和青少年阶段社会适应功能差异(Ding et al., 2023; 万旋傲 等, 2021), 仍缺乏更广年龄阶段的直接比较。因此, 未来研究不仅需要通过大样本横向研究进一步比较从童年期到老年期独处的益处与代价, 更重要的是, 也需要通过纵向研究更加全面地考察同一批个体在发展的不同阶段中, 独处的益处和代价如何动态变化的全过程。最后, 还可以借助元分析帮助我们更加直观、细致地了解独处与个体适应功能各个指标之间的关系与差异。

8.3 结合文化背景理解独处的发展过程

在理解独处现象时, 不得不考虑的是文化因素, 因为不同文化中对于独处的态度和理解存在一定差异, 而对文化差异性的考量有助于更好地理解独处这一现象(Buttrick et al., 2019; 丁雪辰 等, 2015; 丁雪辰 等, 2019)。例如, 西方文化更加强调个体的自由意志, 独处更可能被理解为个人选择, 从而得到更多接纳(Bowker et al., 2020)。相反, 在东方文化中更加看重人际关系与群体互动, 因此独处更可能被看作是一种自私或是与社会规范不符的行为(Chen, 2020), 因而对个体发展产生更多的消极影响(Liu et al., 2018)。然而, 目前大多数关于独处的研究多基于西方文化样本(Coplan, Ooi, et al., 2019; Thomas & Azmitia, 2019; Weinstein & Nguyen, 2020), 在东方文化下的探索则较为有限, 目前仅有少数研究探索儿童和青少年的独处(Ding et al., 2020; Liu et al., 2018; Zhang & Eggum- Wilkens, 2017; Zhang & Eggum‐Wilkens, 2018), 能够支撑不同文化间比较的研究证据还相对不平衡, 因此未来需要更多来自东方文化下的研究证据(包括定性和定量研究), 来描述和揭示独处在不同文化下如何被人们所理解, 以及这种文化差异又是如何进一步影响个体的发展结果。

8.4 数字技术发展下独处的界定与发展

Coplan和Bowker (2017)认为独处代表一种精神状态, 而不是一种存在状态, 而当代数字技术的发展可以使个体既可能在物理空间上独处, 同时在虚拟的网络世界中与他人进行互动(Quandt & Kr?ger, 2013), 这似乎使得“独自一人”难以将独处概念化(Campbell & Morgan, 2022)。人们可能会发问: 独处的定义是否应该包括各种不涉及社会互动的想法、感觉、行为, 如睡觉、玩电子游戏、线上客户服务、解决问题等活动(Hoppmann & Pauly, 2022)。过去研究发现仅仅是对于电子通信软件即时反馈的期望就可以打断个体的独处(Kushlev et al., 2017), 而近年Coplan等人(2022)专门关注到青少年独处与数字科技使用, 研究结果强调探讨独处与幸福感之间的联系时考虑数字技术的重要性。另有研究发现在疫情期间经常与他人进行虚拟互动的老年人会受益(Tsang et al., 2022)。但目前仅有少量研究关注到数字科技如何影响个体独处的适应功能(Coplan et al., 2022; Diefenbach & Borrmann, 2019; Tsang et al., 2022), 因此未来研究需要关注在网络高速发展的时代背景下, 独处的概念及其对于不同年龄段个体的发展是否存在新的模式与适应功能, 尤其在童年期和成年中期就线上独处展开充分讨论。

8.5 独处的认知神经机制

基于毕生发展的视角探讨独处离不开脑结构和功能的变化。随着认知神经科学技术的兴起, 独处认知神经机制的发展也是未来研究中不可或缺的一部分。早期关于社会退缩儿童认知神经活动表现的研究证据从侧面提供了一些支持, 社会退缩儿童往往会存在社交趋近?回避动机的冲突(Poole et al., 2019), 有研究发现, 在静息状态下, 社会退缩儿童右脑额叶表现出相对较强烈的EEG活动, 因此他们更容易出现消极的情绪与回避行为(Fox et al., 1995)。但社会退缩并不能完全等同于独处, 最近Huang等人(2023)的研究直接关注了独处动机与趋近?回避动机之间的关联程度, 研究者们通过收集18~45岁大学生(M = 19.77岁)静息态EEG下三种常见的与趋近?回避动机相关的神经生理信号FAA、β抑制和PFTA, 发现独处的神经生理基础仅与趋近?回避系统的情绪(FAA)和身体运动(β抑制)方面有关。具体而言, 独处偏好与FAA呈负相关, 较高的独处水平与相对较少的左额叶不对称有关, 作者认为这样的结果难以确定偏好独处的个体是因为他们更少体验到趋近?回避情绪, 还是因为他们并不擅长情绪调节。另外, 独处偏好还与β抑制的增加有关, 这可能是因为偏好独处的个体拥有丰富的内心活动, 充满了自我反思和创造力, 这种心智化可能是个体通过回忆过去或想象未来的互动和行为所驱动的(Huang et al., 2023)。从发展的视角来看, 前额叶在25岁之间会继续发育和成熟(Johnson et al., 2009), 因而未来需要更多研究探索不同时期独处的脑机制, 以及不同时期独处与适应功能之间关联的脑机制, 以解释独处是否随年龄增长对大脑结构和功能产生不同的影响, 以及不同的生理指标是否与个体各个时期的思维模式和社会能力相关联, 从而为个体寻求积极的独处方式提供研究证据。

8.6 不同年龄阶段下独处的实践意义

基于发展的视角, 不同年龄阶段的个体独处的益处和代价也有所差异。针对此, 我们可以通过采用不同的干预措施更有效地发挥独处的积极作用, 减少独处的消极影响。面对独处不利于社会性发展的童年期独处个体(Ding et al., 2015; Ding et al., 2019), 可以依据情境的变化来灵活应对。例如, 当儿童主动独自进行搭积木活动时(Coplan et al., 2014), 我们可以任其享受自己独自探索的时光, 但在其他同伴互动情境鼓励偏好独处儿童参与其中。而对因数字技术的冲击缺乏社会互动而表现高孤独感、低心理健康水平的青少年(Twenge et al., 2019), 我们应当加以重视, 鼓励其参与现实中的亲子互动与同伴互动。虽然成年早期的个体忙于工作, 他们渴望独处用于休息(Toyoshima & Sato, 2015), 但是他们面临另一种风险: 处于单身阶段, 经常独自一人, 没有伴侣来分享闲暇时间(Anttila et al., 2020; Toyoshima & Sato, 2015)。该阶段他们重要的发展任务为亲密关系, 所以我们提倡成年早期个体在保证必要的独处时间用于休息恢复精力之外, 应当积极参与社交活动。至于成年中期的个体, 因其工作及养育压力面临较多独处不足的问题, 而扩大家庭物理空间不失为增加独处时间的一个有效手段(Anttila et al., 2020)。另外, 近期一项研究证实: 人生后半阶段, 积极独处的技能与通过听音乐或正念调节情绪的技能相关, 这为改善晚年生活提供了启示(Bachman et al., 2022)。

参考文献

陈晓, 周晖. (2012). 自古圣贤皆“寂寞”?——独处及相关研究. 心理科学进展, 20(11), 1850?1859.

丁雪辰, 张田, 邓欣媚, 桑标, 方力, 程琛. (2015). “孤芳自赏”还是“茕茕孑立”: 儿童社交淡漠适应功能的文化差异. 心理科学进展, 23(3), 439?447.

丁雪辰, 周同, 张润竹, 周楠. (2019). 儿童社交回避行为: 成因、测量方式及适应功能. 心理科学, 42(3), 604?611.

万旋傲, 张雯, 周同, 尚琪, 丁雪辰, 徐刚敏. (2021). 儿童社交淡漠与学业成绩的发展轨迹: 基于潜变量增长模型. 心理科学, 44(4), 858?865.

Anttila, T., Selander, K., & Oinas, T. (2020). Disconnected lives: Trends in time spent alone in Finland. Social Indicators Research, 150(2), 711?730.

Ardelt, M., & Grunwald, S. (2018). The importance of self-reflection and awareness for human development in hard times. Research in Human Development, 15(3?4), 187?199.

Bachman, N., Palgi, Y., & Bodner, E. (2022). Emotion regulation through music and mindfulness are associated with positive solitude differently at the second half of life. International Journal of Behavioral Development, 46(6), 520?527.

Birditt, K. S., Manalel, J. A., Sommers, H., Luong, G., & Fingerman, K. L. (2018). Better off alone: Daily solitude is associated with lower negative affect in more conflictual social networks. The Gerontologist, 59(6), 1152?1161.

Borg, M. E., & Willoughby, T. (2022). Affinity for solitude and motivations for spending time alone among early and mid-adolescents. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 51(1), 156?168.

Borg, M. E., & Willoughby, T. (2023). When is solitude maladaptive for adolescents? A comprehensive study of sociability and characteristics of solitude. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 52(12), 2647?2660.

Bowker, J. C., Nelson, L. J., Markovic, A., & Luster, S. (2014). Social withdrawal during adolescence and emerging adulthood. In R. J. Coplan & J. C. Bowker (Eds.), A handbook of solitude: Psychological perspectives on social isolation, social withdrawal, and being alone (pp. 167?183). New York: Wiley-Blackwell.

Bowker, J. C., Ooi, L. L., Coplan, R. J., & Etkin, R. G. (2020). When is it okay to be alone? Gender differences in normative beliefs about social withdrawal in emerging adulthood. Sex Roles, 82(7/8), 482?492.

Bowker, J. C., & Raja, R. (2011). Social withdrawal subtypes during early adolescence in India. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 39(2), 201?212.

Bowker, J. C., Rubin, K. H., & Coplan, R. J. (2016). Social withdrawal. In R. J. R. Levesque (Ed.), Encyclopedia of adolescence (2nd ed., pp. 1?14). Switzerland: Springer, Cham.

Bowker, J. C., Stotsky, M. T., & Etkin, R. G. (2017). How BIS/BAS and psycho-behavioral variables distinguish between social withdrawal subtypes during emerging adulthood. Personality and Individual Differences, 119, 283?288.

Bowker, J. C., White, H. I., & Etkin, R. G. (2021). Social withdrawal during adolescence. In R. J. Coplan, J. C. Bowker, & L. J. Nelson (Eds.), The Handbook of Solitude (pp. 133?145). New York: Wiley-Blackwell.

Burger, J. M. (1995). Individual differences in preference for solitude. Journal of Research in Personality, 29(1), 85? 108.

Buttrick, N., Choi, H., Wilson, T. D., Oishi, S., Boker, S. M., Gilbert, D. T., … Wilks, D. C. (2019). Cross-cultural consistency and relativity in the enjoyment of thinking versus doing. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 117(5), e71?e83.

Campbell, S. W., & Ross, M. Q. (2022). Re-conceptualizing solitude in the digital era: From “being alone” to “noncommunication”. Communication Theory, 32(3), 387? 406.

Chen, X. (2020). Exploring cultural meanings of adaptive and maladaptive behaviors in children and adolescents: A contextual-developmental perspective. International Journal of Behavioral Development, 44(3), 256?265.

Chen, X., Wang, L., & Cao, R. (2011). Shyness-sensitivity and unsociability in rural Chinese children: Relations with social, school, and psychological adjustment. Child Development, 82(5), 1531?1543.

Chui, H., Hoppmann, C. A., Gerstorf, D., Walker, R., & Luszcz, M. A. (2014). Social partners and momentary affect in the oldest-old: The presence of others benefits affect depending on who we are and who we are with. Developmental Psychology, 50(3), 728?740.

Coplan, R. J., & Bowker, J. C. (2017). “Should we be left alone?” Psychological perspectives on the costs and benefits of solitude. In I. Bergmann, & S. Hilppler (Eds.), Cultures of Solitude: Loneliness, Limitation, and Liberation (pp. 287?302). Frankfurt: Peter Lang.

Coplan, R. J., Bowker, J. C., & Nelson, L. J. (2021). Alone again: Revisiting psychological perspectives on solitude. In R. J. Coplan, J. C. Bowker, & L. J. Nelson (Eds.), The Handbook of Solitude: Psychological perspectives on social isolation, social withdrawal, and being alone (2nd ed., pp. 3?15). New York: Wiley-Blackwell.

Coplan, R. J., Girardi, A., Findlay, L. C., & Frohlick, S. L. (2007). Understanding solitude: Young childrens attitudes and responses toward hypothetical socially withdrawn peers. Social Development, 16(3), 390?409.

Coplan, R. J., Hipson, W. E., Archbell, K. A., Ooi, L. L., Baldwin, D., & Bowker, J. C. (2019). Seeking more solitude: Conceptualization, assessment, and implications of aloneliness. Personality and Individual Differences, 148, 17?26.

Coplan, R. J., Hipson, W. E., & Bowker, J. C. (2021). Social withdrawal and aloneliness in adolescence: Examining the implications of too much and not enough solitude. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 50(6), 1219?1233.

Coplan, R. J., McVarnock, A., Hipson, W. E., & Bowker, J. C. (2022). Alone with my phone? Examining beliefs about solitude and technology use in adolescence. International Journal of Behavioral Development, 46(6), 481?489.

Coplan, R. J., Ooi, L. L., & Baldwin, D. (2019). Does it matter when we want to be alone? Exploring developmental timing effects in the implications of unsociability. New Ideas in Psychology, 53, 47?57.

Coplan, R. J., Ooi, L. L., & Hipson, W. E. (2021). Solitary activities from early childhood to adolescence: Causes, content, and consequences. In R. J. Coplan, J. C. Bowker, & L. J. Nelson (Eds.), The Handbook of Solitude: Psychological perspectives on social isolation, social withdrawal, and being alone (2nd ed., pp. 105?116). New York: Wiley-Blackwell.

Coplan, R. J., Ooi, L. L., Rose-Krasnor, L., & Nocita, G. (2014). ‘I want to play alone: Assessment and correlates of self-reported preference for solitary play in young children. Infant and Child Development, 23(3), 229?238.

Coplan, R. J., Rose-Krasnor, L., Weeks, M., Kingsbury, A., Kingsbury, M., & Bullock, A. (2013). Alone is a crowd: Social motivations, social withdrawal, and socioemotional functioning in later childhood. Developmental Psychology, 49(5), 861?875.

Coplan, R. J., Zelenski, J., & Bowker, J. C. (2018). Leave well enough alone? The costs and benefits of solitude. In J. E. Maddux (Ed.), Subjective well-being and life satisfaction (pp. 129?147). New York: Routledge.

Corsano, P., Grazia, V., & Molinari, L. (2019). Solitude and loneliness profiles in early adolescents: A person-centred approach. Journal of Child and Family Studies, 28(12), 3374?3384.

Courtin, E., & Knapp, M. (2017). Social isolation, loneliness and health in old age: A scoping review. Health and Social Care in the Community, 25(3), 799?812.

Danneel, S., Maes, M., Vanhalst, J., Bijttebier, P., & Goossens, L. (2018). Developmental change in loneliness and attitudes toward aloneness in adolescence. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 47(1), 148?161.

Diefenbach, S., & Borrmann, K. (2019, May). The smartphone as a pacifier and its consequences. Paper presented at the meeting of CHI 19: Proceedings of the 2019 CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems, Glasgow Scotland, UK.

Diekema, D. A. (1992). Aloneness and social form. Symbolic Interaction, 15(4), 481?500.

Ding, X., Chen, X., Fu, R., Li, D., & Liu, J. (2020). Relations of shyness and unsociability with adjustment in migrant and non-migrant children in urban China. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 48(2), 289?300.

Ding, X., Coplan, R. J., Deng, X., Ooi, L. L., Li, D., & Sang, B. (2019). Sad, scared, or rejected? A short-term longitudinal study of the predictors of social avoidance in Chinese children. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 47(7), 1265?1276.

Ding, X., Weeks, M., Liu, J., Sang, B., & Zhou, Y. (2015). Relations between unsociability and peer problems in Chinese children: Moderating effect of behavioural control. Infant and Child Development, 24(1), 94?103.

Ding, X., Zhang, W., Ooi, L., Coplan, R. J., Zhu, X., & Sang, B. (2023). Relations between social withdrawal subtypes and socio-emotional adjustment among Chinese children and early adolescents. Journal of Research on Adolescence, 33(3), 774?785.

Dong, S., Dong, Q., Chen, H., & Yang, S. (2022). Mothers parenting stress and marital satisfaction during the parenting period: Examining the role of depression, solitude, and time alone. Frontiers in Psychology, 13, 847419.

Fiori, K. L., Smith, J., & Antonucci, T. C. (2007). Social network types among older adults: A multidimensional approach. The Journals of Gerontology: Series B: Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences, 62(6), 322? 330.

Fox, N. A., Schmidt, L. A., Calkins, S. D., Rubin, K. H., & Coplan, R. J. (1996). The role of frontal activation in the regulation and dysregulation of social behavior during the preschool years. Development and Psychopathology, 8(1), 89?102.

Fromm-Reichmann, F. (1959). (1959). Loneliness. Psychiatry, 22(1), 1?15.

Golden, J., Conroy, R. M., Bruce, I., Denihan, A., Greene, E., Kirby, M., & Lawlor, B. A. (2009). Loneliness, social support networks, mood and wellbeing in community- dwelling elderly. International Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry, 24(7), 694?700.

Gornik, A. E., Neal, J. W., Lo, S. L., & Durbin, C. E. (2018). Connections between preschoolers temperament traits and social behaviors as observed in a preschool setting. Social Development, 27(2), 335?350.

Hipson, W. E., Coplan, R. J., Dufour, M., Wood, K. R., & Bowker, J. C. (2021). Time alone well spent? A person-centered analysis of adolescents solitary activities. Social Development, 30(4), 1114?1130.

Hoppmann, C. A., Lay, J. C., Pauly, T., & Zambrano, E. (2021). Social isolation, loneliness, and solitude in older adulthood. In R. J. Coplan, J. C. Bowker, & L. J. Nelson (Eds.), The handbook of solitude: Psychological perspectives on social isolation, social withdrawal, and being alone (2nd ed., pp. 178?189). New York: Wiley-Blackwell.

Hoppmann, C. A., & Pauly, T. (2022). A lifespan psychological perspective on solitude. International Journal of Behavioral Development, 46(6), 473?480.

Hu, N., Xu, G., Chen, X., Yuan, M., Liu, J., Coplan, R. J., Li, D., & Chen, X. (2022). A parallel latent growth model of affinity for solitude and depressive symptoms among Chinese early adolescents. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 51(5), 904?914.

Huang, C., Butterworth, J. W., Finley, A. J., Angus, D. J., Sedikides, C., & Kelley, N. J. (2023). There is a party in my head and no one is invited: Resting-state electrocortical activity and solitude. Journal of Personality, Advance online publication.

Johnson, S. B., Blum, R. W., & Giedd, J. N. (2009). Adolescent maturity and the brain: The promise and pitfalls of neuroscience research in adolescent health policy. Journal of Adolescent Health, 45(3), 216?221.

Katz, J. C., & Buchholz, E. S. (1999). “I did it myself”: The necessity of solo play for preschoolers. Early Child Development and Care, 155(1), 39?50.

Korpela, K., & Staats, H. (2021). Solitary and social aspects of restoration in nature. In R. J. Coplan, J. C. Bowker, & L. J. Nelson (Eds.), The handbook of solitude: Psychological perspectives on social isolation, social withdrawal, and being alone (2nd ed., pp. 325?339). New York: Wiley- Blackwell.

Kushlev, K., Proulx, J. D. E., & Dunn, E. W. (2017). Digitally connected, socially disconnected: The effects of relying on technology rather than other people. Computers in Human Behavior, 76, 68?74.

Ladd, G. W., Ettekal, I., & Kochenderfer-Ladd, B. (2019). Longitudinal changes in victimized youths social anxiety and solitary behavior. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 47(7), 1211?1223.

Ladd, G. W., Kochenderfer-Ladd, B., Eggum, N. D., Kochel, K. P., & McConnell, E. M. (2011). Characterizing and comparing the friendships of anxious-solitary and unsociable preadolescents. Child Development, 82(5), 1434?1453.

Lang, F. R., & Baltes, M. M. (1997). Being with people and being alone in late life: Costs and benefits for everyday functioning. International Journal of Behavioral Development, 21(4), 729?746.

Larson, R. W. (1990). The solitary side of life: An examination of the time people spend alone from childhood to old age. Developmental Review, 10(2), 155?183.

Lay, C. J., Pauly, T., Graf, P., Biesanz, J. C., & Hoppmann, C. A. (2018). By myself and liking it? Predictors of distinct types of solitude experiences in daily life. Journal of Personality, 87(3), 633?647.

Lay, J. C., Fung, H. H., Jiang, D., Lau, C. H., Mahmood, A., Graf, P., & Hoppmann, C. A. (2019). Solitude in context: On the role of culture, immigration, and acculturation in the experience of time to oneself. International Journal of Psychology, 55(4), 562?571.

Lay, J. C., Pauly, T., Graf, P., Mahmood, A., & Hoppmann, C. A. (2020). Choosing solitude: Age differences in situational and affective correlates of solitude-seeking in midlife and older adulthood. The Journals of Gerontology: Series B: Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences, 75(3), 483?493.

Leary, M. R., Herbst, K. C., & McCrary, F. (2003). Finding pleasure in solitary activities: Desire for aloneness or disinterest in social contact? Personality and Individual Differences, 35(1), 59?68.

Li, K., & Tang, F. (2022). The role of solitary activity in moderating the association between social isolation and perceived loneliness among US older adults. Journal of Gerontological Social Work, 65(3), 252?270.

Liu, J., Bullock, A., Coplan, R. J., Chen, X., Li, D., & Zhou, Y. (2018). Developmental cascade models linking peer victimization, depression, and academic achievement in Chinese children. British Journal of Developmental Psychology, 36(1), 47?63.

Liu, J., Chen, X., Coplan, R. J., Ding, X., Zarbatany, L., & Ellis, W. (2015). Shyness and unsociability and their relations with adjustment in Chinese and Canadian children. Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology, 46(3), 371?386.

Long, C. R., & Averill, J. R. (2003). Solitude: An exploration of benefits of being alone. Journal for the Theory of Social Behaviour, 33(1), 21?44.

Luo, M., Pauly, T., R?cke, C., & Hülür, G. (2022). Alternating time spent on social interactions and solitude in healthy older adults. British Journal of Psychology, 113(4), 987?1008.

Maes, M., Vanhalst, J., Spithoven, A. W., van den Noortgate, W., & Goossens, L. (2016). Loneliness and attitudes toward aloneness in adolescence: A person-centered approach. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 45(3), 547? 567.

Mehta, C. M., Arnett, J. J., Palmer, C. G., & Nelson, L. J. (2020). Established adulthood: A new conception of ages 30 to 45. American Psychologist, 75(4), 431?444.

Nelson, L. J., Hart, C. H., & Evans, C. A. (2008). Solitary- functional play and solitary-pretend play: Another look at the construct of solitary-active behavior using playground observations. Social Development, 17(4), 812?831.

Nguyen, T. T., Ryan, R. M., & Deci, E. L. (2018). Solitude as an approach to affective self-regulation. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 44(1), 92?106.

Nguyen, T., Weinstein, N., & Ryan, R. M. (2022). Who enjoys solitude?Autonomous functioning (but not introversion) predicts self-determined motivation (but not preference) for solitude. PLoS ONE, 17(5), 1?18.

Nguyen, T. T., Werner, K. M., & Soenens, B. (2019). Embracing me-time: Motivation for solitude during transition to college. Motivation and Emotion, 43(4), 571?591.

Nikitin, J., Rupprecht, F. S., & Ristl, C. (2022). Experiences of solitude in adulthood and old age: The role of autonomy. International Journal of Behavioral Development, 46(6), 510?519.

Ost Mor, S., Palgi, Y., & Segel-Karpas, D. (2020). The definition and categories of positive solitude: Older and younger adults perspectives on spending time by themselves. The International Journal of Aging and Human Development, 93(4), 943?962.

Pauly, T., Chu, L., Zambrano, E., Gerstorf, D., & Hoppmann, C. A. (2022). COVID-19, time to oneself, and loneliness: Creativity as a resource. The Journals of Gerontology: Series B, 77(4), e30?e35.

Pauly, T., Lay, J. C., Scott, S. B., & Hoppmann, C. A. (2018). Social relationship quality buffers negative affective correlates of everyday solitude in an adult lifespan and an older adult sample. Psychology and Aging, 33(5), 728? 738.

Poole, K. L., Santesso, D. L., van Lieshout, R. J., & Schmidt, L. A. (2019). Frontal brain asymmetry and the trajectory of shyness across the early school years. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 47(7), 1253?1263.

Quandt, T., & Kr?ger, S. (2013). Multiplayer. The social aspects of digital gaming. Routledge.

Robb, C. E., de Jager, C. A., Ahmadi-Abhari, S., Giannakopoulou, P., Udeh-Momoh, C., McKeand, J., ... Middleton, L. (2020). Associations of social isolation with anxiety and depression during the early COVID-19 pandemic: A survey of older adults in London, UK. Frontiers in Psychiatry, 11, 591120.

Rubin, K. H. (1982). Nonsocial play in preschoolers: Necessarily evil? Child Development, 53(3), 651?657.

Rubin, K. H., Barstead, M. G., Smith, K. A., & Bowker, J. C. (2018). Peer relations and the behaviorally inhibited child. In K. Pérez-Edgar (Eds.), Behavioral Inhibition (pp. 157?184). Switzerland: Springer, Cham.

Rubin, K. H., Bukowski, W. M., & Bowker, J. C. (2015). Children in peer groups. In M. H. Bornstein, T. Leventhal, & R. M. Lerner (Eds.), Handbook of child psychology and developmental science: Ecological settings and processe (Vol. 4, 7th ed., pp. 175?222). New York: Wiley- Blackwell.

Rubin, K. H., Burgess, K. B., & Hastings, P. D. (2002). Stability and social-behavioral consequences of toddlers inhibited temperament and parenting behaviors. Child Development, 73(2), 483?495.

Smith, K. A., Hastings, P. D., Henderson, H. A., & Rubin, K. H. (2019). Multidimensional emotion regulation moderates the relation between behavioral inhibition at age 2 and social reticence with unfamiliar peers at age 4. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 47(7), 1239?1251.

Teppers, E., Klimstra, T. A., van Damme, C., Luyckx, K., Vanhalst, J., & Goossens, L. (2013). Personality traits, loneliness, and attitudes toward aloneness in adolescence. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships, 30(8), 1045?1063.

Thomas, V., & Azmitia, M. (2019). Motivation matters: Development and validation of the motivation for solitude scale—Short Form (MSS-SF). Journal of Adolescence, 70, 33?42.

Toyoshima, A., & Sato, S. (2015). Examination of the relationship between preference for solitude and emotional well-being after controlling for the effect of loneliness. Japanese Journal of Psychology, 86(2), 142?149.

Toyoshima, A., & Sato, S. (2019). Examination of the effect of preference for solitude on subjective well-being and developmental change. Journal of Adult Development, 26(2), 139?148.

Tsang, V. H. L., Tse, D. C. K., Chu, L., Fung, H. H., Mai, C., & Zhang, H. (2022). The mediating role of loneliness on relations between face-to-face and virtual interactions and psychological well-being across age: A 21-day diary study. International Journal of Behavioral Development, 46(6), 500?509.

Tse, D. C. K., Lay, J. C., & Nakamura, J. (2022). Autonomy matters: Experiential and individual differences in chosen and unchosen solitary activities from three experience sampling studies. Social Psychological and Personality Science, 13(5), 946?956.

Twenge, J. M., Spitzberg, B. H., & Campbell, W. K. (2019). Less in-person social interaction with peers among U.S. adolescents in the 21st century and links to loneliness. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships, 36(6), 1892?1913.

Victor, C. R., & Bowling, A. (2012). A longitudinal analysis of loneliness among older people in Great Britain. The Journal of Psychology, 146(3), 313?331.

Wagner, M., Schütze, Y., & Lang, F. R. (1999). Social relationships in older age. In P. B. Baltes & K. U. Mayer (Eds.), The Berlin Aging Study: Aging from 70 to 100 (pp. 282?301). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Wang, J. M., Rubin, K. H., Laursen, B., Booth-LaForce, C., & Rose-Krasnor, L. (2013). Preference-for-solitude and adjustment difficulties in early and late adolescence. Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology, 42(6), 834?842.

Weinstein, N., & Nguyen, T. V. (2020). Motivation and preference in isolation: A test of their different influences on responses to self-isolation during the COVID-19 outbreak. Royal Society Open Science, 7(5), 200458.

Weinstein, N., Nguyen, T. T., & Hansen, H. (2021). What time alone offers: Narratives of solitude from adolescence to older adulthood. Frontiers in Psychology, 12, 714518.

Winnicott, D. W. (1958). The capacity to be alone. International Journal of Psycho-Analysis, 39, 416?420.

Wood, K. R., Coplan, R. J., Hipson, W. E., & Bowker, J. C. (2022). Normative beliefs about social withdrawal in adolescence. Journal of Research on Adolescence, 32(1), 372?381.

Yang, P., Coplan, R. J., Zhang, Y., Ding, X., & Zhu, Z. (2023). Assessment and implications of aloneliness in Chinese children and early adolescents. Journal of Applied Developmental Psychology, 85, 1?9.

Yuan, J., & Grühn, D. (2022). Preference and motivations for solitude in established adulthood: Antecedents, consequences, and adulthood phase differences. Journal of Adult Development, 30(5), 64?77.

Zava, F., Watanabe, L. K., Sette, S., Baumgartner, E., Laghi, F., & Coplan, R. J. (2019). Young childrens perceptions and beliefs about hypothetical shy, unsociable, and socially avoidant peers at school. Social Development, 29(1), 89?109.

Zhang, L., & Eggum-Wilkens, N. D. (2017). Correlates of shyness and unsociability during early adolescence in urban and rural China. The Journal of Early Adolescence, 38(3), 408?421.

Zhang, L., & Eggum-Wilkens, N. D. (2018). Unsociability in Chinese adolescents: Cross-informant agreement and relations with social and school adjustment. Social Development, 27(3), 555?570.

Zhou, T., Liao, L., Nguyen, T. -V. T., Li, D., & Liu, J. (2023). Solitude profiles and psychological adjustment in Chinese late adolescence: A person-centered research. Frontiers in Psychiatry, 14, 1173441.

Zunzunegui, M. V., Alvarado, B. E., Del Ser, T., & Otero, A. (2003). Social networks, social integration, and social engagement determine cognitive decline in community- dwelling Spanish older adults. The Journals of Gerontology Series B: Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences, 58(2), S93?S100.

Understanding the adjustment functions of solitude from a lifespan development perspective: A five-round comparison of benefits and costs

Abstract: Solitude, a state of non-communication with others in a real or virtual environment, has positive or negative effects on individuals across different stages of life, from childhood to late adulthood. Previous studies have focused on the adjustment function of solitude, but have taken different views on it, either positive or negative. This study adopts a lifespan development perspective to describe the adjustment function of solitude at different ages and highlights that solitude has both benefits and costs. To further develop our understanding of solitude, future studies could: 1) Integrate the multi-dimensional and dynamic development of solitude from a personal-oriented perspective. 2) Collect more cross-sectional and longitudinal data from lifespan perspective. 3) Interpret the development process of solitude based on cultural background. 4) Examine the impact of contemporary digital technology on individual experience of solitude. 5) Explore the cognitive neural mechanisms of solitude. 6) Consider the practical implications of solitude at different developmental stages.

Keywords: solitude, lifespan development perspective, adjustment function, benefit, cost