Morphology and morphometry of two hybridizing buntings at their hybrid zone in northern Iran reveal intermediate and transgressive morphotypes

Ali Gholamhosseini, Mansour Aliaaian, Till T¨opfer, Glenn-Peter Sætre

aOrnithology Research Laboratory,Department of Biology,School of Science,Shiraz University,Shiraz,Iran

bDepartment of Biology,Faculty of Sciences,Ferdowsi University of Mashhad,Mashhad,Iran

cLeibniz Institute for the Analysis of Biodiversity Change,Zoological Research Museum Alexander Koenig,Centre for Taxonomy and Morphology,Bonn,Germany

dCentre for Ecological and Evolutionary Synthesis(CEES),Department of Biosciences,University of Oslo,Norway

Keywords:Bunting Hybridization Intermediate phenotypes Transgressive traits

ABSTRACTThe closely related Black-headed Bunting (Emberiza melanocephala, a western Palearctic lineage) and Red-headed Bunting (Emberiza bruniceps, an eastern Palearctic lineage) hybridize and replace each other south of the Caspian Sea.The parental species have distinct phenotypes and therefore morphology is useful for assessing hybridization in the contact zone.In the years of 1940 and 1977, quite a few hybrids were collected and studied morphologically.Since then, the hybrid zone appears to have expanded westwards, but there has been a time gap in the collection of morphological data.Here we reanalyze bunting specimens morphologically and compare the historical data with recent data.Morphometric and phenotypic traits from three time periods (1940, 1977 and recent) were studied to assess phenotypic variation of hybrids, pattern of hybridization, and transgressive traits in the hybrid zone.Our results show that most of the birds in the hybrid zone exhibit intermediate phenotypes(both colors and morphometric characters), ranging from the pure phenotype of either of the parental species.However, hybridization has also produced novel phenotypes not seen in any of the parents.Using a canonical discriminant function analysis, the morphometric characters separated each parental species and the hybrids quite well.Our results showed morphometric intermediacy of hybrids in accordance with phenotypes.We observe a time trend in which recent hybrids are more similar to Red-headed Buntings phenotypically compared to historical samples.This pattern is likely a signature of a westward expansion of the Red-headed Bunting into the breeding range of the Black-headed Bunting.

1.Introduction

Hybridization is relatively common in birds (Grant and Grant, 1994;McCarthy, 2006; Aliabadian and Nijman, 2007) and could play an important role in speciation, and hence provide new material for evolution (Newton, 2003; Price, 2008).Interbreeding between distinct bird species with different phenotypic and morphometric traits can result in a variety of hybrid individuals with intermediate or mixed character states.Where morphologically dissimilar bird species come into contact,morphological cues are usually the first signs of hybridization.Paludan(1940) and Haffer (1977) used such morphological data for detecting hybrids between the two closely related species, Black-headed Bunting(Emberiza melanocephalaScopoli, 1769)—a western Palearctic lineage,and Red-headed Bunting (Emberiza brunicepsBrandt, 1841)—an eastern Palearctic lineage, south of the Caspian Sea (Fig.1).

The two bunting species are sexually dimorphic, with males being strikingly dissimilar in several color patterns, whereas females are almost inseparable.Male Red-headed Bunting are of two distinct forms,apparently without any geographical pattern.In the common form, the head including the crown, ear-coverts, throat and upper breast are bright chestnut colored.The nape and mantle are olive-green with some darker streaks on the mantle.The sides of the neck, underparts and rump is yellow (Fig.2).In the other less common form, the chestnut color is more limited on the head and the crown is almost yellow (see Byers et al., 1995).Non-breeding males are similar to the breeding adults but have restricted amount of red on the head and feathers of the fresh plumage have pale fringes.Breeding males of the Black-headed Bunting have a black hood, bright yellow underparts, and a cinnamon to light chestnut mantle (Fig.2).The latter color is variably extending to the sides of the breast.The yellow color on the sides of the neck may connect and form a complete yellow collar in some males (Haffer, 1977; Byers et al., 1995).The Black-headed Bunting is larger, heavier and has a more pointed wing tip than the Red-headed Bunting (Haffer, 1977).

Fig.1.Approximate breeding range of Black-headed and Redheaded Buntings(after Haffer, 1977 and modified by Gholamhosseini A.).

Natural hybridization often occurs between closely related bird species (Gholamhosseini et al., 2013).According to Alstr¨om et al.(2008), P¨ackert et al.(2015) and Cai et al.(2021), the two bunting species are sister species, but with a relatively large genetic divergence.The contact zone between these buntings has been the subjected to some studies.Nikol’skiy (1886) collected both species in the Abr region (NE Shahrud, N Iran) without finding any hybrids.Paludan (1940) and Haffer (1977) reported interbreeding of these buntings in northern Iran and individuals of both parental species and as well as a few hybrid specimens collected in connection to these studies are still available for analysis.Haffer concluded that these buntings formed a restricted zone of overlap and hybridization in northern Iran, south of the Elburz Mountains, which was about 90 km wide (Bastam valley and Meyamey area) and consisted of both pure parental phenotypes (65–70%) and hybrids (30–35%).He reported a similar zone of hybridization north of the Elburz Mountains between Behshahr and Gorgan, but here these birds are less common than south of the Elburz Mountains (Fig.2).

A recent westward expansion of the Red-headed Bunting into the geographical range of the Black-headed Bunting has been reported along the south of Caspian Sea (Gholamhosseini et al., 2017).The western edge of the hybrid zone has expanded by approximately 170 km during the last four decades.Many years have lapsed since the latest collections in the hybrid zone (Paludan, 1940; Haffer, 1977).It is likely that the recent expansion of the hybrid zone has changed the pattern of hybridization.Therefore, we re-analysed previously collected bunting specimens in this expanding hybrid zone and added recent ones.We assigned morphometric and phenotypic traits of specimens from three time periods, 1940, 1977 and recent, to assess morphometric and phenotypic variation of hybrids through time, pattern of hybridization,and to look for transgressive traits.Hybrids may exhibit intermediate traits compared to their parental forms, or transgressive traits which are novel traits in the hybrids distinct from or outside the range of those of the parental lineages (Mérot et al., 2020).

2.Materials and methods

2.1.Historical and recent sampling

Paludan (1940) identified five hybrids out of 22 collected male buntings from southeast of the Caspian Sea (Abr region) and presented an illustrated color plate of the hybrids.Later, Haffer (1977) identified 19 hybrids out of 53 collected specimens in northern Iran.About 27 of the 53 specimens collected by Haffer were from the sympatric area, and the rest from allopatric populations.For studying variation in the hybrids, we not only paid attention to the collected historical samples, but also to Paludan’s and Haffer’s observations and reports.For convenience of comparison, we prepared a color plate from Haffer’s hybrid samples deposited in the Zoological Research Museum Alexander Koenig(ZFMK).We compared these historical samples and observations with birds sampled and photographed during 2011–2022.The latter birds were caught using mist nets and song playbacks in northern Iran, from the easternmost parts of Iran to the west, a range more than 1200 km long, covering the regions both south and north of the Elburz Mountains,and photographed using Canon SX 30 and Canon EOS 760D camera equipped with a Sigma 150–600 mm lens.

2.2.Hybrid identification

To identify hybrids, we accepted Paludan’s and Haffer’s decisions on the historical collected specimens and for recently specimens, we followed Haffer (1977) and also paid attention to our results from the phenotypic examinations.To identify hybrids, some morphological traits was carefully considered, which are explained in the following.

2.2.1.Head

Fig.2.Historical hybrid zone between Red-headed and Black-headed Buntings in north of Iran reported by Haffer (1977) are indicated by blue color from Meyamey(Ma) in the east to Mojan (Mo) in the west in south of Elburz Mountains and between Gorgan (Go) and Behshar (Be) in north of Elburz Mountains.Recent extent of the hybrid zone reported by Gholamhosseini et al.(2017) are indicated by pink hatch lines.Red color indicates breeding range of Red-headed Bunting and grey color indicates breeding range of Black-headed bunting in Iran.Pictures of adult males of the two species are presented in the upper corners of the map.Symbols: Ma(Mayemey), Ab (Abr), Sh (Shahrud), Mo (Mojan), Go (Gorgan), Be (Behshahr), Di (Dibaj), Da (Damghan), Sa (Sari), Se (Semnan), Fi (Firuzkola).

In the Red-headed Bunting, the chestnut color of the crown varied from dark chestnut to bright chestnut.In a few pure specimens, the crown is yellowish, but not completely yellow.In the Black-headed Bunting, the crown is black.In non-breeding Black-headed Bunting,the crown may be obscured by sandy fringes or in first-winter male with grayish-brown.We took care not to misidentify these as hybrids by closely examining the individual feathers of the crown.

2.2.2.Chin,throat,and breast

Black-headed Bunting has a yellow chin, throat and breast whereas Red-headed Bunting has red-brown chin, throat and breast.We classified black-crowned birds with chestnut or reddish color in these parts and red-crowned birds with yellow feathers in these parts as putative hybrids.The sides of the breast are rufous in many studied Black-headed Bunting specimens but yellow in others (restricted or slightly extended).We considered this to be intraspecific variation.In a few studied Blackheaded buntings, the chestnut color of both sides of the breast extends slightly to the body flanks.We consider also this as intraspecific variation.

2.2.3.Mantle

The breeding males of the Black-headed Bunting have chestnutcolored upperparts while those of the Red-headed Bunting have greenish upperparts with dark streaks.We classified breeding blackcrowned males with green mantle or dark streaks and breeding redcrowned males with chestnut mantle as putative hybrids.However,because the mantle of adult non-breeding Black-headed Bunting specimens have dark streaks similar to those of the Red-headed Bunting, and also because non-breeding males of Red-headed Bunting specimens have streaked mantle with a rufous tinge, we took care to identify nonbreeding specimens correctly as such, to avoid misidentifying them as hybrids.

2.2.4.Rump

The Black-headed Bunting is reported to have a rufous brown or slightly paler rufous, tinged yellowish rump whereas Red-headed Bunting have bright yellow or yellowish–green ones.Due to the great variation in the rump color of Black-headed Bunting from dark chestnut to yellowish brown, rump color alone may not be a very reliable trait for identifying hybrids.We classified black-crowned birds with an extensive yellow rump and red-crowned birds with a clear rufous brown rump as putative hybrids.

2.3.Morphology and morphometry studies

We investigated plumage color variation of the males of both parental species to determine hybrids and transgressive plumage color traits.We followed the description by Byers et al.(1995) for both parental species.A large number of pure adult males were examined,including specimens photographed by the first author during fieldwork(about 125 Red-headed Buntings and 80 Black-headed Buntings);specimens caught using mist net from our fieldwork (51 Red-headed buntings, 12 hybrids, 15 Black-headed buntings): as well as museum specimens [Zoological Research Museum Alexander Koenig (ZMFK): 29 Red-headed Buntings, 20 hybrids and 37 Black-headed Buntings;Zoological museum of Tehran University (ZMTU): 12 Black-headed Buntings; Zoological museum of Shiraz University, Collection of Biology Department (ZM-CBSU): 6 Black-headed Buntings].

The following measurements were obtained using a digital caliper(precision 0.01 mm): bill length to skull (BL), bill width at the rear of the nostril (BW), bill height at the rear of the nostril (BH), wing length (WL),tail length (TL), tarsus length (TaL), first secondary to the wing tip(S1Wt), tip of the longest alula to the wing tip (AtWt).

2.4.Data analyses

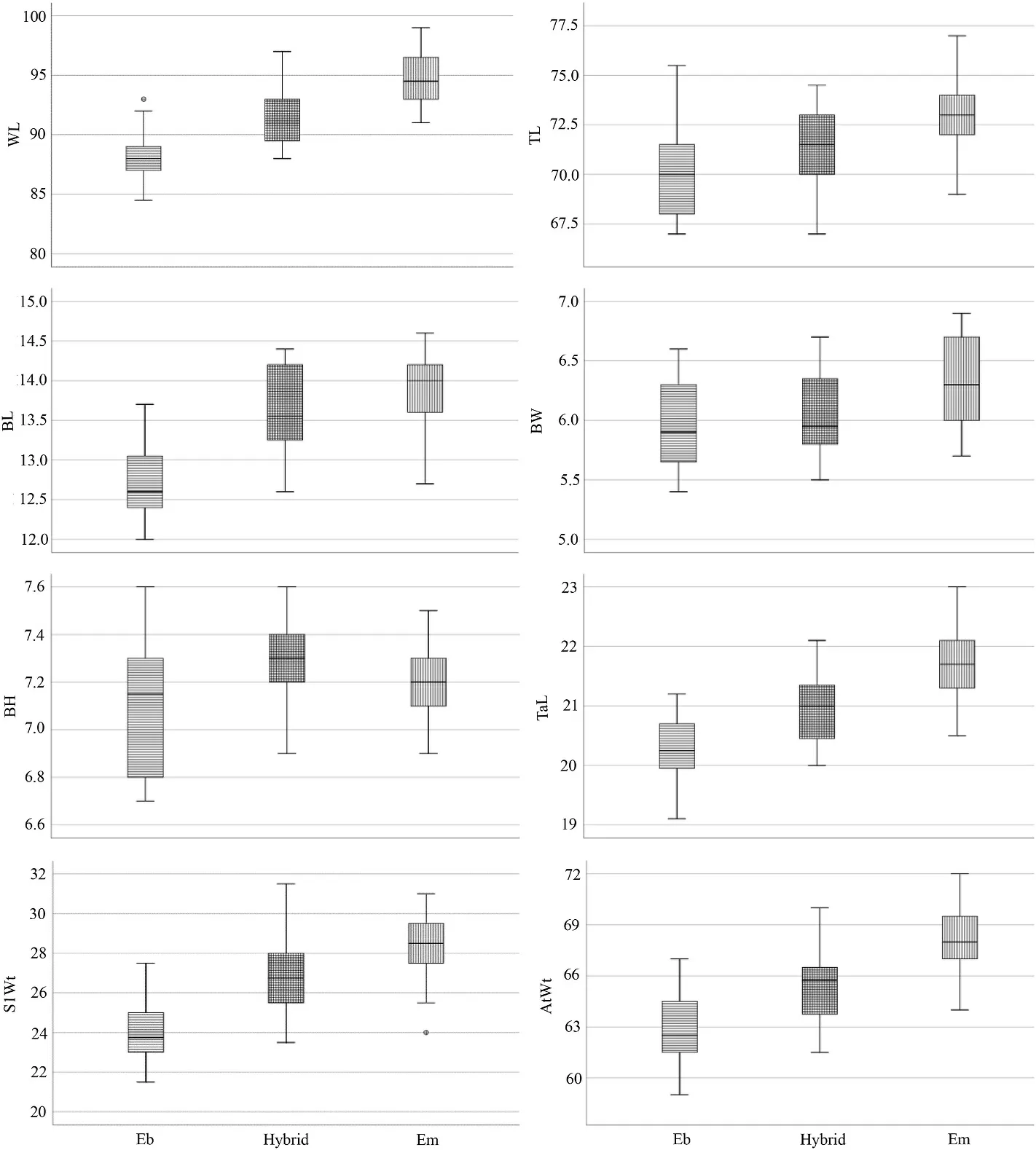

Color traits that were not observed and that have not been reported in any of the parental species were considered as transgressive traits.A Canonical Discriminant Function (CDF) was employed in order to evaluate the actual degree of discrimination among each lineage as well as to predict classification success in both parental species and hybrids and to test to what extent hybrids are morphometrically intermediate.Since the taxidermy treatments of specimens may have an effect on the size of some parameters and integration of their data with measured live specimens may cause bias in results, separate analyses were performed for live birds and museum specimens.Univariate analysis of variance(ANOVA) was carried out to test the significance of morphometric differences among parents and hybrids in IBM SPSS Statistics 26.We used a Boxplot graphic to compare hybrids and parental species at each measured character.

3.Results

3.1.Phenotypic variation of hybrids in the historical collected specimens

3.1.1.Paludan,1940

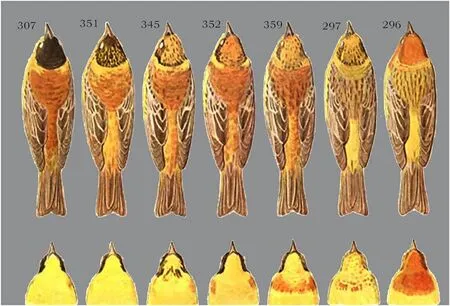

Paludan collected five putative hybrids between the Red-headed and Black-headed Buntings in the Abr region (NE Shahrud), all of which showed clear transitions between the parental species in various traits(Fig.3).This area was the only known sympatric area in those days.The results of that study indicated that the color of the crown, ear coverts,mantle, rump, throat and breast can be used for identification of hybrids,and these putative hybrids were clearly different from either of the parental species.A total of four out of the five hybrids had red brown mantle, red brown rump and black ear coverts, which made them look more like a Black-headed than a Red-headed Bunting.In adult Blackheaded Buntings (No.307 in Fig.3), the feathers on the mantle are red-brown without dark shaft stripes, whereas in Red-headed Buntings(No.296 in Fig.3) they are greenish-yellow with dark shaft stripes.These features are combined in the specimen No.359.Regarding head,mantle and breast color, this specimen can be considered as intermediate.

Paludan only observed a few Red-headed Bunting at Fasalabad (east Gorgan, north of the Elburz Mountains).Out of three individuals collected, two specimens were classified as putative hybrids but more similar to the Red-headed bunting than the other parent species.No pure Black-headed Buntings were found in this region.

In total, three out of seven putative hybrids collected by Paludan south and north of the Elburz Mountains were more similar to the Redheaded Bunting than to the other parent species; one was intermediate;and three were more similar to the Black-headed bunting.Based on Paludan’s observation in the Abr region (N Shahrud) (see Fig.2), the Black-headed bunting was the predominant species, presumably 5–10 times as numerous as the Red-headed Bunting.

3.1.2.Haffer,1977

Haffer (1977) reported that the hybrid zone ranged from Meyamey in the east to Mojan in the west (approximately 90 km) (Fig.2).Among the 23 male Buntings observed or collected in the westernmost location at Mojan, one appeared to be pure Red-headed, whereas all others were apparently pure Black-headed or nearly so.

Near Bastam Valley and Abr, in central parts of the hybrid zone, he observed 22 males (some of which were collected) of which 12 were pure Black-headed Buntings, eight were hybrids (five were most similar to Black-headed Bunting) and two were Red-headed Buntings.

Finally, most of the 20–25 males observed at Meyamey, at the easternmost location, were phenotypically pure Red-headed, except for one male which was more or less pure Black-headed and one other male had a hybrid phenotype (No.22 in Fig.4).Thus, according to Haffer (1977)the hybrid zone between Meyamey in the east and Mojan in the west contained mostly Red-headed Buntings in the east and mostly Black-headed Buntings in the west.Most hybrids were phenotypically closer to the Black-headed than to the Red-headed Bunting.

Fig.3.Hybrid specimens between Red-headed and Black-headed buntings collected by Paludan in 1935 from Abr region (northern Iran) deposited in the Zoological Museum of the University of Copenhagen.307: pure Black-headed Bunting, 296: pure Red-headed Bunting and the rest presented the hybrid specimens.

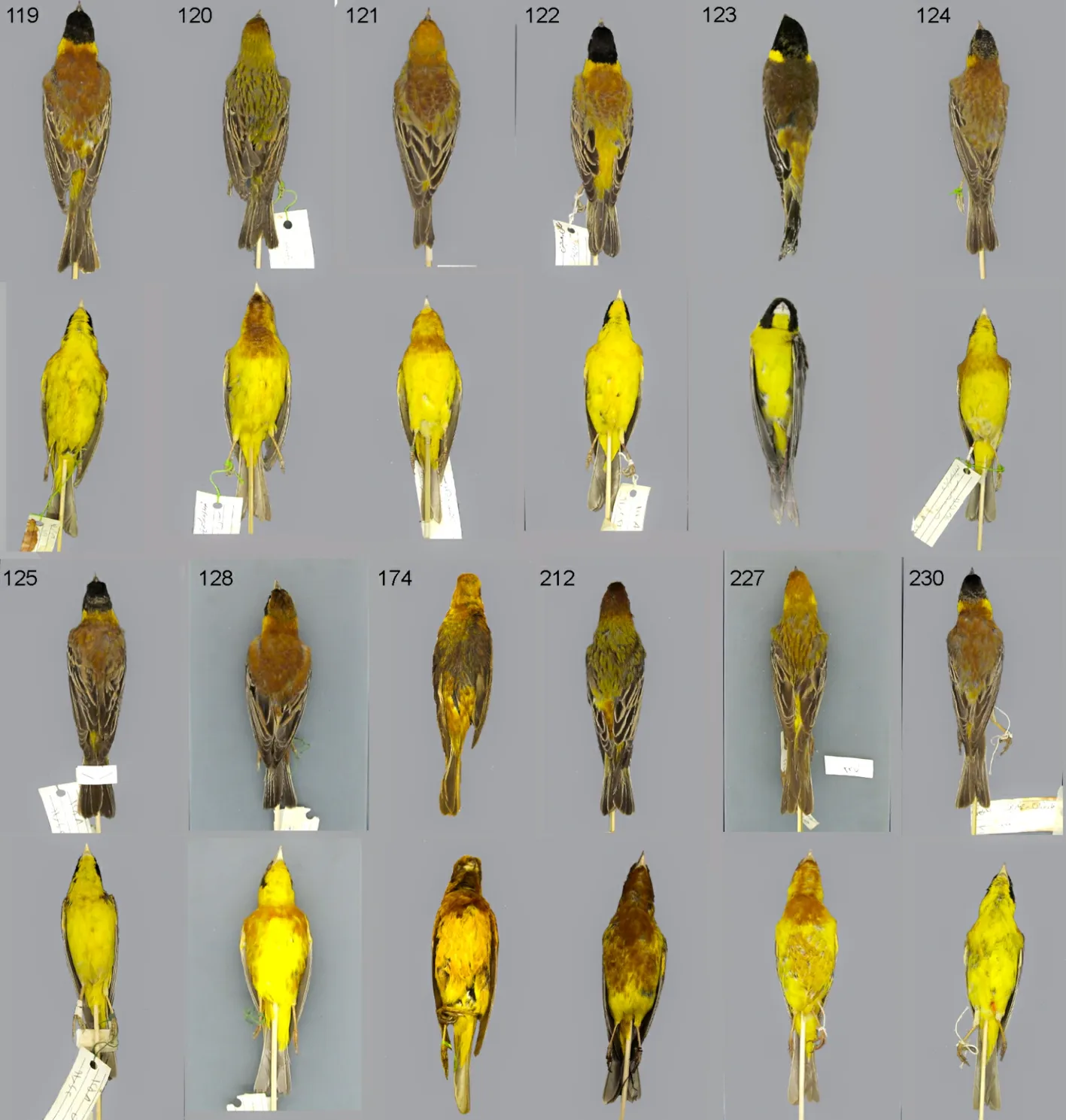

Fig.4.Hybrid specimens between Red-headed and Black-headed Buntings collected by Haffer in 1976 from northern Iran and deposited in the Zoological Research Museum Alexander Koenig (ZFMK).Localities: 1977.022 (Meyamey), 1977.023 (N of Shahrud), 1977.024 (Abr), 1977.025 (Abr), 1977.026 (Abr), 1977.027 (Abr),1977.028 (Abr), 1977.029 (NW Shahrud), 1977.030 (Mojan), 1977.031 (Abr), 1977.032 (Abr), 1977.033 (Mojan), 1977.034 (Mojan), 1977.035 (Mojan), 1977.036(Mojan), 1977.037 (Mojan), 1977.038 (Mojan), 1977.039 (Mojan), 1977.040 (Mojan).

Among the hybrid specimens collected by Haffer (1977) (Fig.4), No.22 is more similar to the Red-headed Bunting (from Meyamey, in the east), No.23 and 24 can be considered intermediate (from Bastam and Abr) in central parts of the hybrid zone, whereas the rest are phenotypically closer to the Black-headed Bunting (from Abr and Mojan,in the central and western part of the hybrid zone).Color patterns suggestive of hybrid origin was found in the head/crown, ear coverts,mantle, rump, throat and breast (Fig.4).

3.2.Phenotypic variation of hybrids in recently collected and photographed specimens

Twenty-six adult male specimens were collected from the hybrid zone south and north of Elburz Mountains during 2011–2022, including nine Red-headed Buntings, five Black-headed Buntings and 12 putative hybrids (Table 1).In total, six hybrid specimens (Fig.5; No.119, 122,123, 124, 125, 230) with black head and rufous mantle were phenotypically more similar to the Black-headed than the Red-headed Bunting, four with red head and breast (No.120, 174, 212, 227) were more similar to the Red-headed than the Black-headed Bunting and two (No.121, 128) had intermediate and mixed characters between the two parental species (Fig.5).Putative hybrid traits were seen in head color,mantle, scapular, rump, throat and breast.

The photographed hybrids possessed many transitional traits between the two parental species.Many kinds of combination and mixing features were seen, especially in the head color, ranging from black to red and mixed with yellow (similar to what can see in Figs.3–5).Although many of the hybrids with red heads have traces of brown on the mantle, some have a completely chestnut colored mantle.On the other hand, although many hybrids with black heads or mixed colored heads have a chestnut-colored mantle, some had a completely yellowish green mantle.Mantle color is important to distinguish hybrids and many putative hybrids had intermediate or mixed mantle color.Some interesting novel color patterns were seen in a combination of head and mantle color, for example hybrids with black head and greenish streaked mantle instead of a simple rufous one.

Most pure Black-headed buntings had a rufous nape and some had a yellow one that forms a yellow collar.On the other hand, in most of Redheaded specimens, the nape is yellowish-green, and some have a yellow collar.Nape feathers of some Red-head specimens outside of the hybrid zone have faint reddish tips (e.g., from Bojnurd, Chaman bid, Sabzevar,Meyamey, Sade-kardeh, Lotfabad, Torbat-heidarieh).In one collected and one observed Red-headed Bunting, the red brown color of the throat and breast extended all the way to the belly and body flanks.No males from outside of the hybrid zone showed this feature.These two birds also had other signs of hybridization.Throat and breast color in putative hybrids showed many transitions between the parental forms as well as some interesting combinations, such as birds with black and red color in the throat simultaneously.

3.3.Hybridization and phenotypic novelties

On the basis of crown, ear coverts, chin, throat, breast, mantle,scapular and rump color, most of the collected or photographed specimens from the hybrid populations are morphologically similar to one of the parental species or intermediate.Yet, some unique color patterns were observed among the putative hybrids that are never found in thepure populations of the parental species east and west of the hybrid zone.Examples of such apparent transgressive traits include the throat of No.345 in Fig.3; the throat of No.24 in Fig.4, the belly of No.212 in Fig.5, and the head, throat, flank, mantle and breast in Fig.6A–F).

Table 1Recently collected specimens of Red-headed and Black-headed Buntings and hybrids (RHB, BHB, H, respectively) from northern Iran in the hybrid zone.

Two collected specimens (No.345 in Fig.3 and No.24 in Fig.4) and six photographed specimens from the area of hybridization had black feathers or yellow feathers with black tips in the throat.This black is restricted as a spot, patch (Fig.6A), extending towards the chin and throat from head or very extensive where the head is completely black(Fig.6B) (see Discussion).

Ear coverts in some hybrids are yellow while ear coverts are black in the Black-headed and Red in Red-headed Buntings.In a few hybrids, the head is completely yellow (Fig.6D).

3.4.Morphometric characters analyses for museum and live specimens

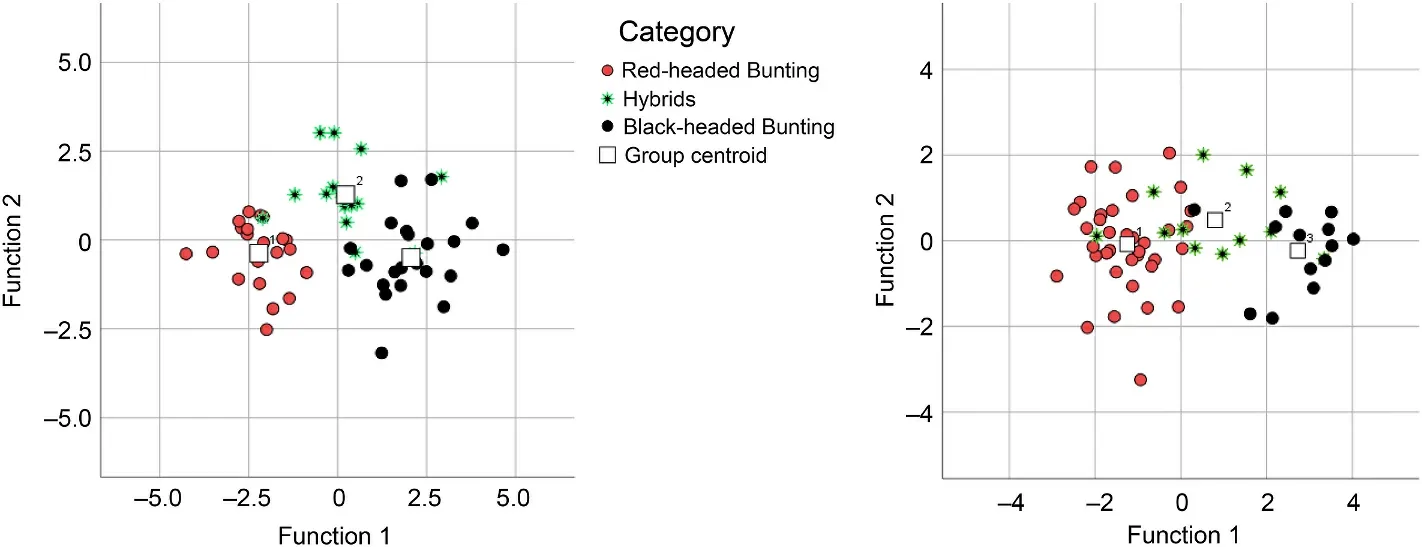

The study of morphometric characters for museum specimens using CDF separated each parent and hybrids quite well (Fig.7).Tests of function 1 and 2 showed significant values; Wilks’ lambda = 0.13,p=0.0001 and Wilks’ lambda = 0.63,p= 0.001 for function 1 and 2 respectively.For all specimens, function 1 contributed 86.1% to the variance (with eigenvalue of 3.61) and function 2 contributed 13.9%(with eigenvalue of 0.58).A total of 89.8% of the original grouped birds were correctly classified.100% of the putative pure Red-headed bunting and 90.9% of the putative Black-headed buntings were classified correctly, whereas 73.3 % of the putative hybrids were classified as such.Of these, respectively 6.7% and 20 % overlapped with Red-headed buntings and Black-headed Buntings.The morphometric characters WL, AtWt, S1Wt, TaL and BL have the greatest effect on the formation of function 1.

The study of morphometric characters for live specimens using CDF separated each parent and hybrids relatively well (Fig.7).In this case,test of function 1 showed a significant value (Wilks’ lambda =0.24,p=0.0001) whereas function 2 was not (Wilks’ lambda = 0.94,p= 0.84).For all specimens, function 1 contributed 97.7% to the variance (with eigenvalue of 2.77) and function 2 contributed 2.3% (with eigenvalue of 0.06).A total of 80.3% of the original grouped birds were correctly classified.A total of 86.1% of the putative Red-headed bunting and 92.3% of Black-headed buntings were classified correctly whereas 50%of the putative hybrids were classified as such.Of these, 25% overlapped with Red-headed buntings and 25% with Black-headed buntings.The morphometric characters AtWt, S1Wt and WL have the greatest effect on the formation of function 1.

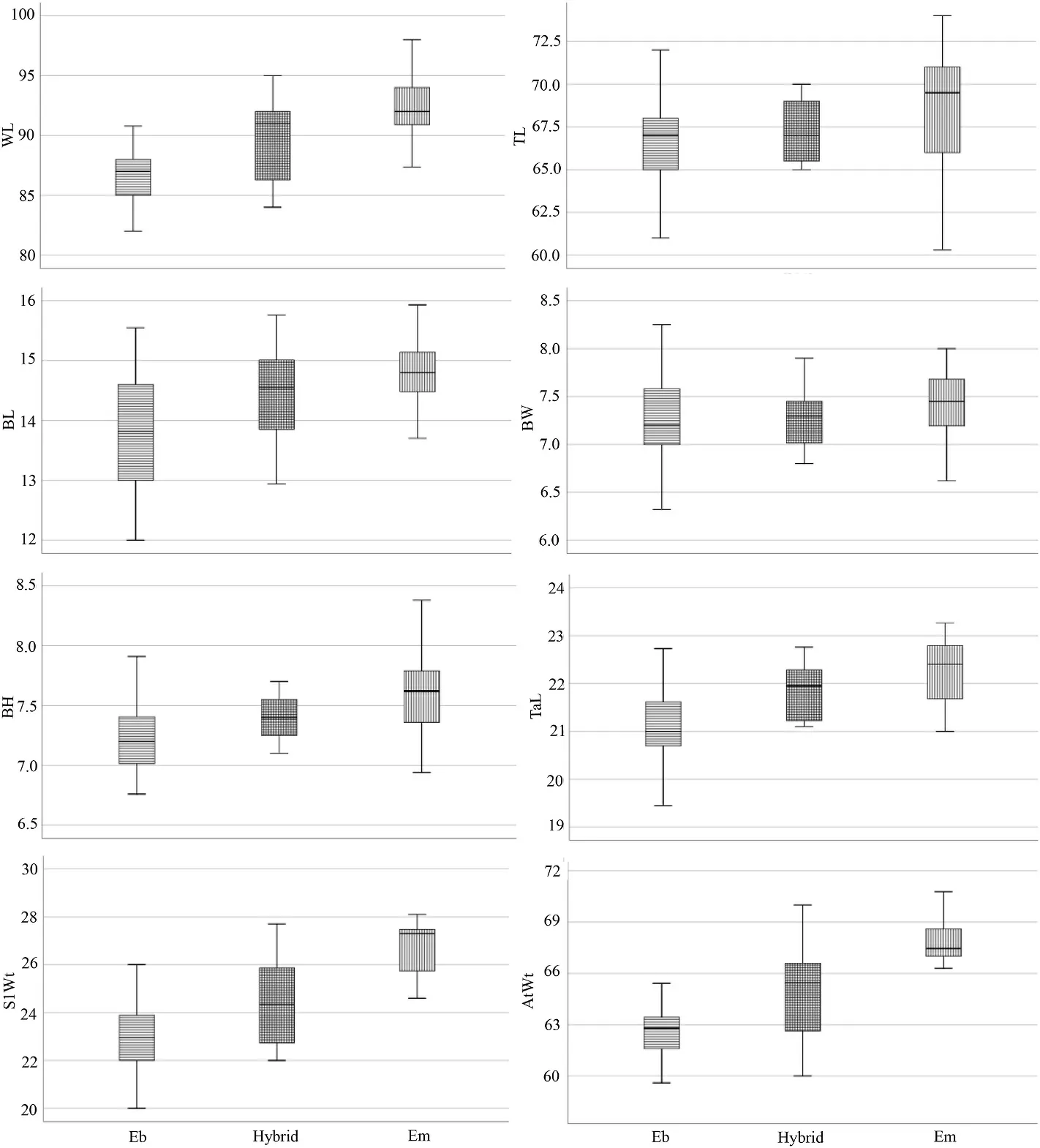

Boxplots showed intermediacy of hybrids relative to the parental species in the means of all measured characters in both museum and live specimens except for BH in the museum samples (Figs.8 and 9).Mean differences are significant (p< 0.05) for all characters in the museum specimens and significant for all characters in the live specimens except for BW.

4.Discussion

In the hybrid zone between the Red-headed and Black-headed Buntings in northern Iran, parental males are easily distinguished morphologically and male hybrids can be recognized using phenotypic traits as they show a variety of intermediate or mosaic characters.Phenotypic signs of hybridization and introgression can be seen in the colors of the head, throat, breast, mantle, scapular, lesser wing coverts and rump.Hybrids may have a complex mosaic of both parental phenotypic characters and/or intermediate phenotypes.Hybrid phenotypes and morphometrics ranged from very close to parental species and all degrees of intermediacy.Specimens with unique color patterns that are not found in any of parental species, that is transgressive traits, are also found in the hybrid zone.

Fig.5.Recently collected hybrids between Red-headed and Black-headed Buntings from northern Iran and deposited in the Zoological Museum of Ferdowsi University of Mashhad.Localities: 119 (Sorkheh, W of Semanan), 120 (Sorkheh, W of Semanan), 121 (Mojan), 122 (Mojan), 123 (Mojan), 124 (Mojan), 125 (Mojan), 128 (Sorkheh, west Semanan), 174 (Bastam, east Shahrud), 212 (Meyamey), 227 (Firuzkola), 230 (Chenar bon, near Firuzkola).

4.1.Phenotypic variation and considerations

Head color and pattern is important to distinguish hybrids and show some novel traits.In some of the specimens collected by Haffer, there are feathers on the back of the head with brownish or yellowish tips.Haffer interpreted this as hybrid traits.Molecular studies are needed to confirm hybrid origin of specimens with these traits.

As the olive color of nape in Red-headed Bunting can extend from the mantle to nape, the chestnut color of the upper head may also sometimes extend to the nape, and the reddish nape of some Red-headed Bunting outside of the hybrid zone may not be the result of gene introgression from the Black-headed Bunting.However, in some of these samples,traces of reddish color can also be seen on the mantle and rump, and this may indicate some introgression of hybrid traits even outside the range of the current hybridization zone.

The dark streaks on the scapular of some adult male Black-headed buntings is most likely just intraspecific variation because this trait observed in a few museum samples from Europe far away from the contact zone.Two breeding Red-headed Buntings outside the current hybrid zone had red streaks on the mantle instead of black or black streaks with brown fringes.It is possible that this is due to introgression beyond the main contact zone.

In a few studied Black-headed buntings, the chestnut color of both sides of the breast extends slightly to the flanks.We consider this trait as regular intraspecific variation whereas extensive chestnut color in the flanks is probably attributed to hybridization.In those specimens that showed such extensive chestnut, other sings of hybridization were observed.

Black-headed Buntings with a completely yellow rump and back were not observed outside the hybrid zone, suggesting that this is a hybrid trait.Rump color is particularly helpful to distinguish hybrids more similar to Red-headed bunting as traces of red color was observed in many of these hybrids.

4.2.Hybrid novelties

Hybrids (especially F1 hybrids) frequently show intermediate or transgressive traits in plants, animals, and fungi (Grant and Grant, 1994;Hermansen et al., 2011; Bello et al., 2018; Campagna et al., 2018;Langdon et al., 2019; Cserkész et al., 2021; Majtyka et al., 2022).Most of the color patterns in the putative hybrids between the two bunting species were intermediate, but we also observed some novel phenotypes in the hybrid zone.It is plausible that hybridization and recombination has produced novel allelic combinations, new epistatic interactions or other complex relationships of genes of color patterns, providing novel color patterns that are not present in either of the parental species.Such novel morphologies may also be produced by novel genes generated through hybridization (Eshed and Zamir, 1996; Chiba, 1997; Stelkens et al., 2009; Shivaprasad et al., 2012).For instance, Papoli Yazdi et al.’s(2022) study of gonad gene expression in House, Spanish and Italian sparrows, highlights the potential for regulation of gene expression to produce novel variation following hybridization.

Fig.7.Scatter plot of the canonical discriminant analysis based on the all-morphometric variables of Red-headed Bunting, Back-headed Bunting and their hybrids(museum specimens on the left and live specimens on the right of the picture).

The Black-headed Bunting has a yellow throat as the rest of the underparts, whereas Red-headed Bunting has a red-brown throat.Some collected specimens from the hybrid zone and photographed specimens have black feathers in the throat (extensive or spotted).In some individuals, the black color of the head is extended from both sides of the chin and throat.Individuals with black throats were not observed in specimens outside the hybrid zone in our fieldwork.However, in some specimens on the Balkan Peninsula (Durazza and Sarpeto; BMNH,AMNH), it has been reported that lateral throat and upper breast are irregularly spotted with black and only one male with entire throat uniformly black (Haffer, 1977).So, the question remains unanswered whether this color pattern is a result of hybrid dispersal outside the hybrid zone or just a rare recombination of genes.Further studies based on the genetic analyses are needed to investigate hybrid origin of these birds and possible dispersal of hybrid traits out of the hybrid zone.In two specimens from the hybrid zone, both black and red feathers were observed in the throat simultaneously.Also, in two specimens from the hybrid zone that had completely black heads, there were other signs of hybridization.Thus, probably this phenomenon (entirely black head) is attributable to hybridization.Molecular studies are suggested to investigate this more closely.

Transgressive hybrid plumage patterns have been reported in Capuchinos by Campagna et al.(2018).They suggested that there may be complex epistatic interactions between the genes controlling coloration and patterning.

Fig.8.Boxplots of the all-morphometric variables of Red-headed Bunting, Back-headed Bunting and their hybrids (museum specimens,p< 0.05).

4.3.Morphometric intermediacy of hybrids

Haffer (1977) showed that Black-headed buntings are larger in length of wing, tail and bill, heavier, and have a more pointed wing tip than Red-headed buntings.Intermediated populations measured by Haffer had sizes between the two parental species in these characters.Our results showed morphometric intermediacy of hybrids in accordance with phenotypes.This intermediacy was observed in all measured characters except for bill height in the museum samples.As the bill is not completely closed in some museum samples and this character show intermediacy in live measured specimens, we did not consider this as out of the parental range.Considering that the shape of the avian beak in speciation, hybrid zone and selection has long been the target of many studies (Darwin, 1859; Eroukhmanoff et al., 2014; Lamichhaney et al.,2018), and advantages of geometric morphometric studies compared to the traditional morphometry, it is suggested to use this technique for evaluation of beak shape in this hybrid region in future studies.

4.4.Structure and dynamics of the hybrid zone

In the specimens collected by Paludan (1940) and Haffer (1977),most of the putative hybrid specimens were more similar to the Black-headed than the Red-headed Buntings, while in the recently collected specimens, a larger number are more similar to the Red-headed Buntings.Although the sampling methods and sample size in these studies differ, the phenotypic shift is quite clear.The phenotypic shift likely reflects an expansion of the hybrid zone towards the west caused by westward expansion of Red-headed Bunting (Gholamhosseini et al., 2017).The observed expansion of Red-headed Buntings to the west is not a result of restricted sampling by Haffer (1977) because his sampling covered the western edge of the hybrid zone.When we compare data from collected specimens and field observations in the past and present, the number of Red-headed buntings is increasing in the eastern and central parts of the hybrid zone relative to the number of Black-headed Bunting.Paludan and Haffer reported that the Black-headed Bunting was dominant in the Bastam valley (NE Shahrud)in central parts of the hybrid zone.In contrast, in our more recent observation, the Red-headed Bunting is clearly dominant in this area,consistent with a western expansion of the hybrid zone.Moreover, the trend of a westward expansion was even evident from within the field data during 2011–2023.

Fig.9.Boxplots of the all-morphometric variables of Red-headed Bunting, Back-headed Bunting and their hybrids (live specimens,p< 0.05).

Krosby and Rohwer (2010) compared recently collected specimens from hybrid zone of Townsend’s Warblers (Dendroica townsendi) and Hermit Warblers (D.occidentalis) where their ranges overlap in Washington and Oregon in the USA, to those collected 10–20 years earlier.Morphological results showed that the newly sampled specimens were more Townsend’s-like than the historical specimens, consistent with ongoing movement of the zone into the geographical range of hermit warblers.The Damselfly (Ischnura elegans) has recently expanded south into the range of morphologically similar sister speciesI.graellsii.Molecular data and niche modelling suggested adaptive trait introgression from the native into the expanding species (Wellenreuther et al., 2018).In a survey of 44 cases of introgression following range expansions, 82%of these studies showed extensive introgression from the resident into the invading species (Currat et al., 2008).In our study new collected specimens is more phenotypically similar to the invading species compared to the historical sampling.A recent westward expansion of Red-headed Buntings to hitherto unoccupied niches is likely to have offered increased opportunities for hybridization and probably gene introgression from the Black-headed to the Red-headed Bunting.At the expansion front, Red-headed Buntings may have lower densities than Black-headed buntings, thus resulting in asymmetric introgression between the two species, with a larger gene flow from the local (Black--headed Bunting) to the invasive (Red-headed Bunting) species than the reverse.However, molecular studies are needed to confirm the pattern of introgression.

Both extrinsic (environmental, such as climate and habitat) and intrinsic (e.g., interaction between species) factors have been proposed to underlie hybrid zone movement and expansion (Buggs, 2007; Taylor et al., 2014; Trier et al., 2014; McQuillan and Rice, 2015).Regarding our field observations, climatically suitable areas for each parental species(Gholamhosseini et al., 2017), comparison of morphometric and phenotypic variation of hybrids through time (this study), some factors such as competition, climate, asymmetric gene flow, sexual selection and land use change may be involved in the expansion of this bunting hybrid zone.

Overall, our study reveals that hybrids between the Red-headed and Black-headed Buntings exhibit a mosaic and intermediate phenotypes ranging from one parental extreme to the other.In addition, hybridization has produced novel, transgressive phenotypes not found in either of the parental species.The extensive phenotypic range of putative hybrids suggests that the sample include backcrosses of various forms in addition to F1 hybrids.Indeed, some birds were phenotypically very close to one of the parental types but exhibited some traits suggestive of being of mixed ancestry.Recently collected hybrid specimens are more phenotypically similar to the invading species (Red-headed Bunting)compared to the historical sampling.This is consistent with a westward movement of the hybrid zone driven by a corresponding range expansion of the Red-headed Bunting.

Funding

We greatly appreciate the financial support from the Shiraz University (during 2015–2022) and Ferdowsi University of Mashhad, Iran(during 2011–2013).

Ethics statement

All work involving live birds for this study was approved by ethics committee of biology department, Shiraz University.

Declaration of competing interest

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

CRediT authorship contribution statement

Ali Gholamhosseini: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Funding acquisition, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Resources, Software, Supervision, Validation, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing.Mansour Aliabadian: Data curation, Investigation, Methodology, Resources,Software, Validation, Visualization, Writing – review & editing, Formal analysis.Till T¨opfer: Data curation, Formal analysis, Investigation,Methodology, Resources, Software, Validation, Visualization, Writing –review & editing.Glenn-Peter Sætre: Data curation, Formal analysis,Investigation, Methodology, Resources, Software, Validation, Visualization, Writing – review & editing.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank the Department of Environment (DOE) for giving permission to AG for sampling (91.51843).We also express our thanks to Mahmood Ghasempouri, Morteza Monfared, Ahamd Mahmoudi, Mojtaba Baniasadi, Hamid Reza Shahbazi and Nasrin Kayvanfar for help in the field.

- Avian Research的其它文章

- Selecting the best: Interspecific and age-related diet differences among sympatric steppe passerines

- Quiet in the nest: The nest environment attenuates song in a grassland songbird

- Characteristics of cross transmission of gut fungal pathogens between wintering Hooded Cranes and sympatric Domestic Geese

- Fecal DNA metabarcoding reveals the dietary composition of wintering Red-crowned Cranes (Grus japonensis)

- Short-term night lighting disrupts lipid and glucose metabolism in Zebra Finches: Implication for urban stopover birds

- Variaiton in the composition of small molecule compounds in the egg yolks of Asian Short-toed Larks between early and late broods