Moderate stepwise restriction of potassium intake to reduce risk of hyperkalemia in chronic kidney disease: A literature review

AlSahow A

Abstract

Key Words: Chronic kidney disease; Potassium intake; Plant-based diet; Hyperkalemia;Potassium removal

INTRODUCTION

A potassium-rich diet has several cardiovascular and renal health benefits[1-4].However, it is not recommended in patients with advanced chronic kidney disease (CKD) or end-stage kidney disease (ESKD) because of the risk of hyperkalemia[5].In fact, restriction of dietary potassium intake is the current standard of care.Due to the lack of strong evidence supporting this approach, there are calls to reevaluate and individualize the potassium dietary advice for patients with CKD[1,2].In this review, the current recommendations, the argument against a restrictive approach, and an individualized, gradual reduction of dietary potassium intake were discussed.

Potassium intake and health

A potassium-rich diet can help decrease blood pressure and the risk of CKD and its progression, cardiovascular disease,stroke, and mortality[1-4].Fruits and vegetables in most diets supply the majority of dietary potassium[5].The alkaline content of such a potassium-rich, plant-based diet may correct CKD-associated metabolic acidosis.Fiber from potassiumrich fruits and vegetables improves the lipid profile, lowers body weight, increases stool volume and frequency, improves colonic epithelium integrity reducing toxin absorption, and improves the gut microbiome reducing systemic inflammation[1-4].The Kidney Disease Outcomes Quality Initiative 2020 nutrition guideline suggested increasing fruit and vegetable intake to help reduce weight, blood pressure, and net acid production, all of which may help lower the rate of CKD progression[6].A plant-based diet also helps decrease the risk of calcium oxalate stone formation by increasing urinary citrate levels and reducing the calcium excretion rate[3].

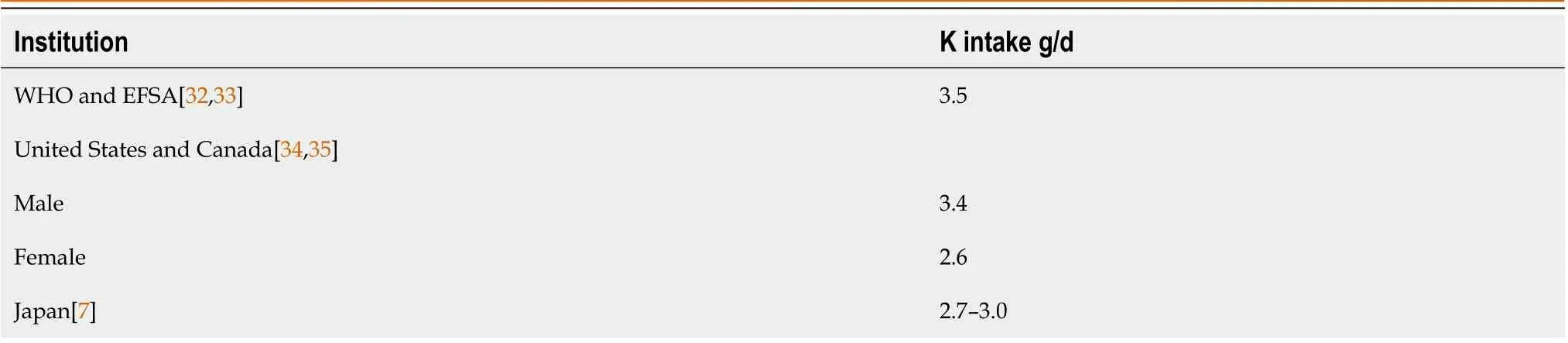

The minimum daily requirement for potassium in adults, estimated based on its unavoidable loss through sweat, stool,urine, and other sources, is about 1.6 g[7].Table 1 Lists the recommended daily intake of potassium for the general population.It is important to know that the majority of people around the world consume less than what is recommended[8-10].

Dietary potassium intake recommendations in adult patients with CKD

Patients with an estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) ≥ 45 mL/min/1.73 m2are generally at low risk of hyperkalemia when consuming the recommended amount of potassium for the general population, even during treatment with renin angiotensin aldosterone system (RAAS) blockers.Hyperkalemia may develop in patients receiving a high dose of RAAS blockers and/or who have a high potassium intake (> 5 g/d) in the presence of severe heart failure and/or diabetes[8].Table 2 outlines the current potassium intake recommendations for patients with advanced CKD(stages 3b-5) and ESKD to avoid hyperkalemia.It reveals a lack of consensus regarding recommendations for a low potassium diet.A low potassium diet is defined as a dietary intake of 2-3g/d of potassium[5].In CKD populations,potassium intake is estimated to average around 2.4 g/d[11].

Uncertainties and challenges of dietary potassium restriction in CKD

Recommendations to limit potassium intake in CKD and ESKD are standard practice for two reasons: to prevent acute hyperkalemia (when postprandial potassium absorption exceeds cellular uptake and body excretion); and to prevent chronic hyperkalemia (when potassium bioaccumulation or total body potassium exceeds cellular uptake and potassium excretion)[12].However, this approach also restricts intake of fruits, vegetables, dairy, grains, nuts, and legumes because they are major sources of potassium[5,12-14].This in turn deprives patients of the health benefits discussed earlier, and it may need to be reevaluated for several reasons.

There is a lack of direct evidence regarding the benefit of restricting potassium intake in CKD from randomized controlled trials[15,16].The results from observational studies regarding the association between higher urinary potassium excretion and mortality and kidney outcomes are conflicting[4,6,15].Dietary potassium restriction is difficult because it requires lifestyle changes that may lead to loss of enjoyment in food and impact social activities.It may result in extra financial costs for special diets[15,16].Restriction may lower the intake of other beneficial nutrients resulting in a poor diet, which may contribute to malnutrition in advanced CKD[17] and may lead to cardiovascular disease[18].

The National Kidney Foundation defines potassium-rich food as food with more than 200 mg of potassium per serving[19].This arbitrary threshold can be confusing.For example, tangerines are a low-potassium food while oranges are a high-potassium food, despite having relatively similar nutrient contents and densities[20].In addition, evidence suggests that gut-kidney kaliuretic signaling initiates urinary potassium excretion before the rise in plasma potassium and independent of plasma potassium and plasma aldosterone[4], which may explain why little to no association exists between serum potassium levels and potassium intake in CKD patients[16,21-24].

An unprocessed plant-based diet rich in potassium may not always lead to hyperkalemia for several reasons.Not all fruits and vegetables are rich in potassium[1].The 24-h urine potassium recovery from animal-based diets is about 80%and from unprocessed plant-based diets is about 50%-60%.This lower bioavailability of unprocessed plant potassium might enable CKD patients to benefit from plant-based diets without precipitating hyperkalemia[1,3,25].Plants are theonly natural source of fiber, a nondigestible, nonabsorbable carbohydrate polymer that increases stool quantity and frequency, facilitating colonic elimination of potassium and protecting against hyperkalemia[3].Plants provide a natural alkali, which may facilitate the transfer of potassium to the intracellular compartment, especially in metabolic acidosis[1,3,5,16].Complex carbohydrates found in fruits and vegetables increase the insulin-mediated cellular uptake of potassium,helping to lower the risk of hyperkalemia[1,3,16].The mineral content of vegetables varies with vegetable size, weather conditions, and cultivation techniques[26].Many dietary recommendations are based on the mineral content of raw whole foods and not chopped, cooked foods[23,27].Restricting sodium intake and encouraging a potassium-rich, plantbased diet may help control hypertension, reducing the need for hyperkalemia-inducing antihypertensive medications,such as β-blockers.It may also allow the reduction of the dosage of RAAS blockers[2], although this approach is controversial due to the negative effects on kidney and patient survival[17,15].

Table 1 Recommended adequate intake of potassium for adults in the general population

Potassium restriction should also be reevaluated because guidelines do not make specific recommendations for potassium in processed food or food additives and do not discuss potassium bioavailability.Potassium additives provide almost three times the amount of potassium found in additive-free counterparts, and potassium additives in processed foods have a high bioavailability contributing to hyperkalemia[24].Because of the pressure on the food industry to decrease sodium in processed food, but not the salty taste, potassium use has increased in low-sodium processed foods[24,28,29].Advice to restrict sodium alone for patients who need dietary sodium and potassium restriction may inadvertently increase potassium intake if a patient unknowingly switches to low-sodium products with potassium additives[30].Moreover, advising CKD patients to restrict potassium-rich food without proper counseling may lead them to choose sodium- and potassium-rich processed foods over healthier alternatives[30].Potassium-based food additives are found in precooked or shelf-stable foods, powdered dressings, sauces, preserved meats, stuffed pasta, jellies, concentrated fruit juices, processed cheeses, and margarine[5].A list of potassium-based food additives is available elsewhere[31].

There are pitfalls associated with the tools used to estimate dietary intake of potassium.Plasma potassium levels are usually measured before hemodialysis and in a fasting state for non-hemodialysis (not a postprandial state).This timing is better suited to evaluate chronic hyperkalemia risk but not to detect acute postprandial hyperkalemia[30].The standard assessment method is a 24-h urine collection, which assumes that 24-h urinary potassium excretion always reflects 70% of ingested potassium.However, collection errors may lead to incorrect assumptions and advice[28].In addition, a single collection cannot accurately estimate potassium intake due to day-to-day variability in intake, gastrointestinal excretion,which is higher at low eGFR, and cell distribution.Spot urine should not be used to estimate intake at an individual level[11,15].

Non-urinary-based dietary assessment tools (food frequency questionnaires, diet records, and 24-h diet recalls) are not affected by changes in potassium homeostasis in CKD but rely on food databases.Thus, database inaccuracies (e.g.,differences in nutrients between processed, restaurant-cooked, and home-cooked foods) can lead to measurement errors[11,15].

Food frequency questionnaires record the consumption frequency of a predefined list of foods and beverages over weeks or months.It is the most cost-effective and time-saving method with a low burden, but errors occur due to recall bias (i.e.,respondents not correctly memorizing intake) and when questionnaires are not relevant to local dietary habits or seasonal changes.Furthermore, they may not account for potassium additives and substitutes and cooking methods[11,15].

Diet recall documents all foods and beverages consumed in the previous 1-7 d with moderate precision, cost, time, and burden.However, the method is prone to recall bias and underreporting, especially in overweight individuals.Precision is acceptable because quantities of consumed foods are defined, including potassium additives and cooking methods.However, more detailed intake information increases data collection complexity[11,15].

Diet records are prospective documentation of intake with minimal recall bias, and it is the most accurate if foods are documented and weighed correctly.However, it is costly and time consuming.Respondents may simplify or underreport complicated meals or even alter eating behaviors choosing healthier foods (selective reporting).Keeping records for more than 4 d may lead to inaccurate results due to respondent fatigue.It is also less suitable for CKD patients, in whom limited health literacy and cognitive impairment are common[11,15].

A gradual, individualized approach

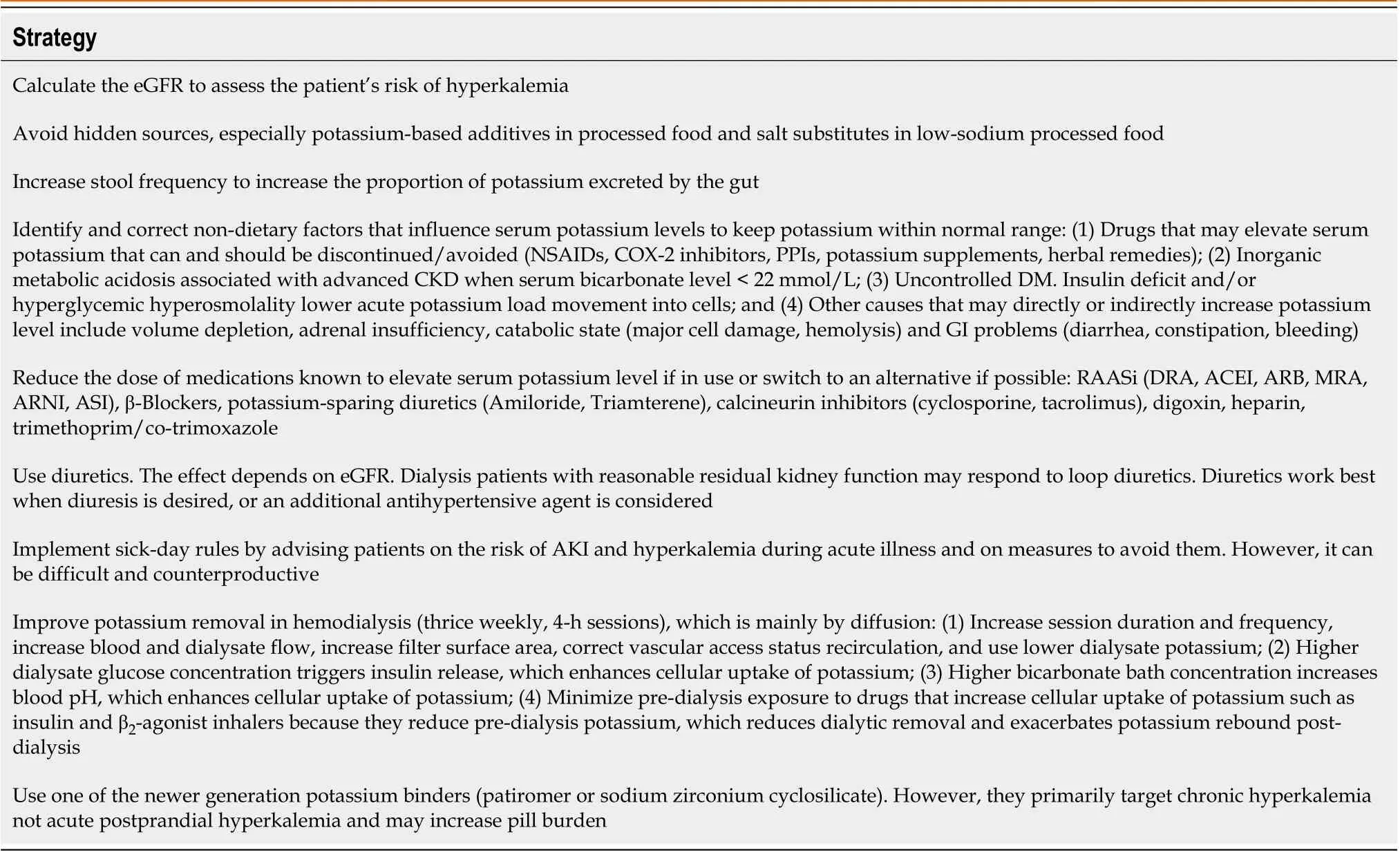

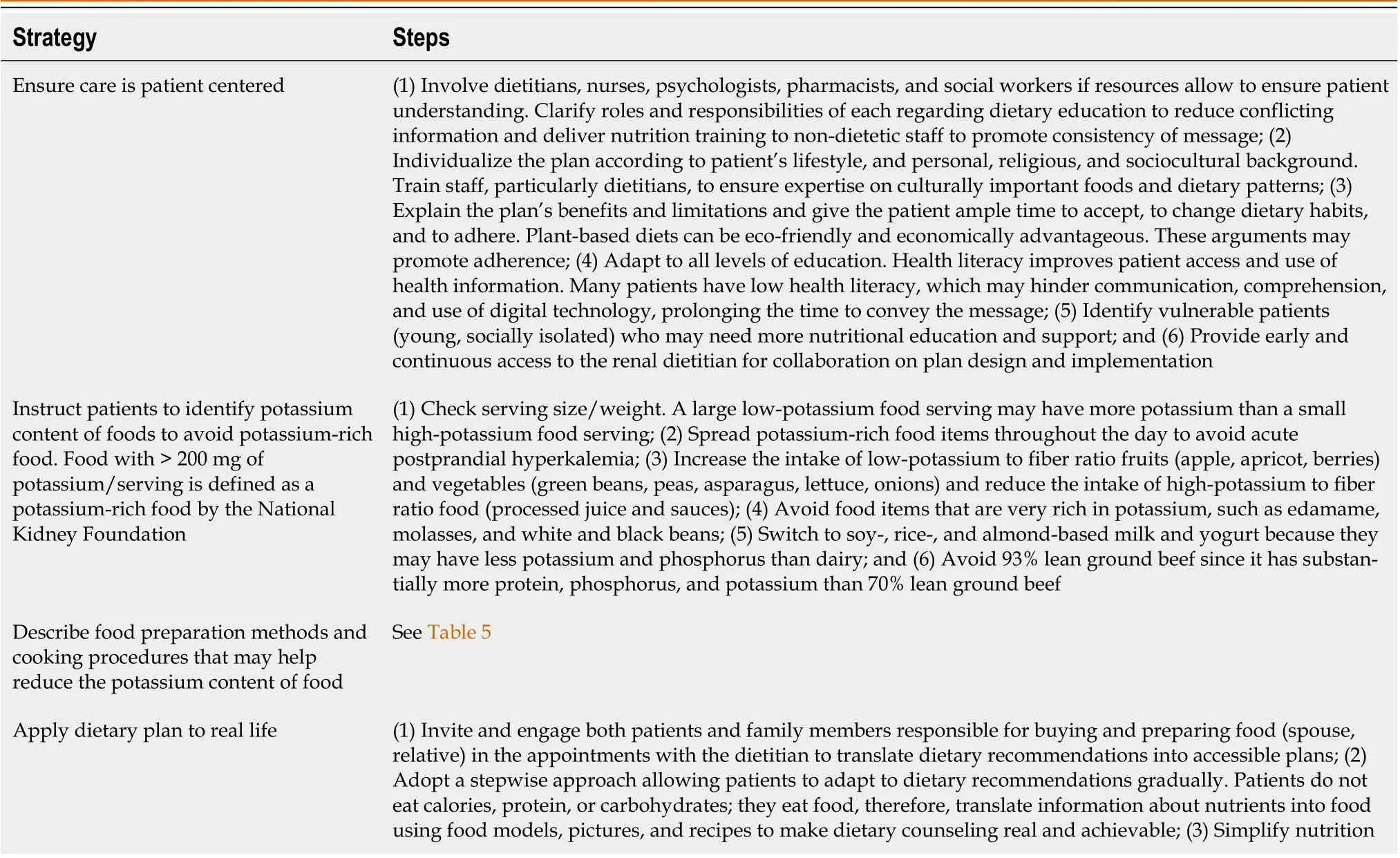

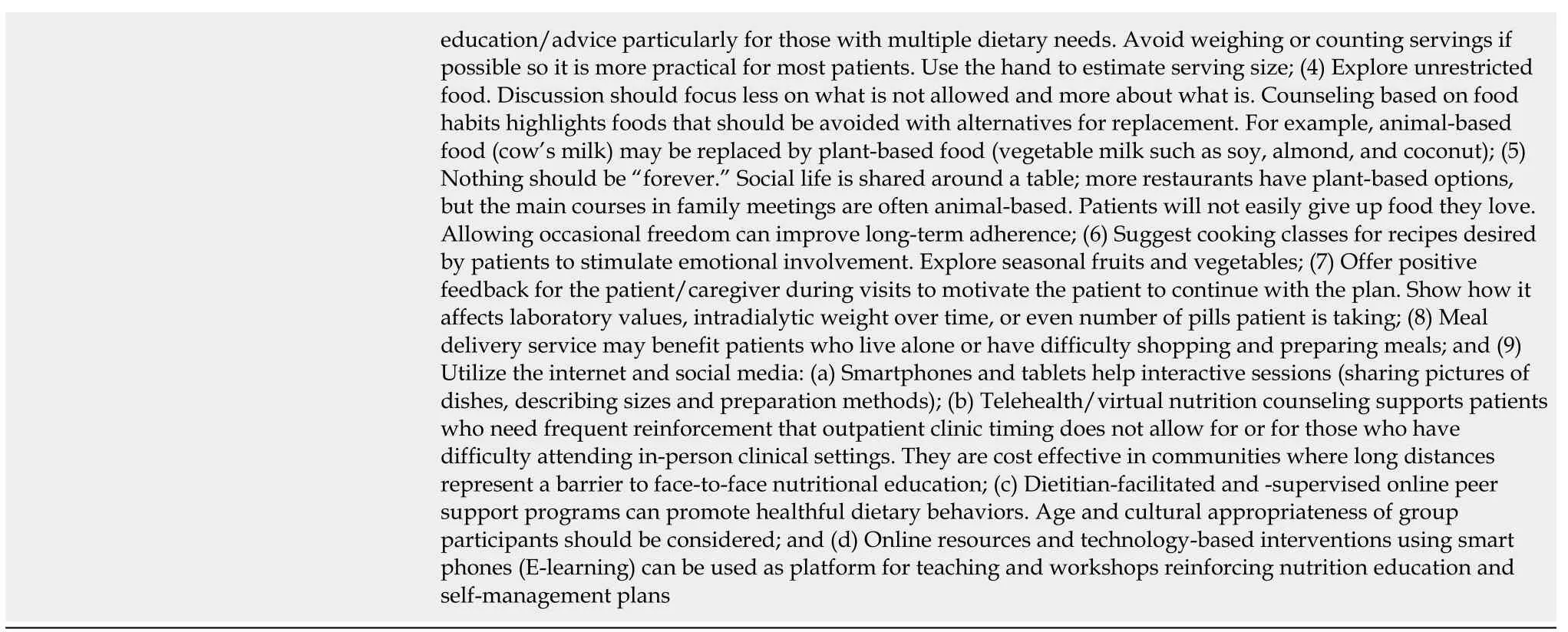

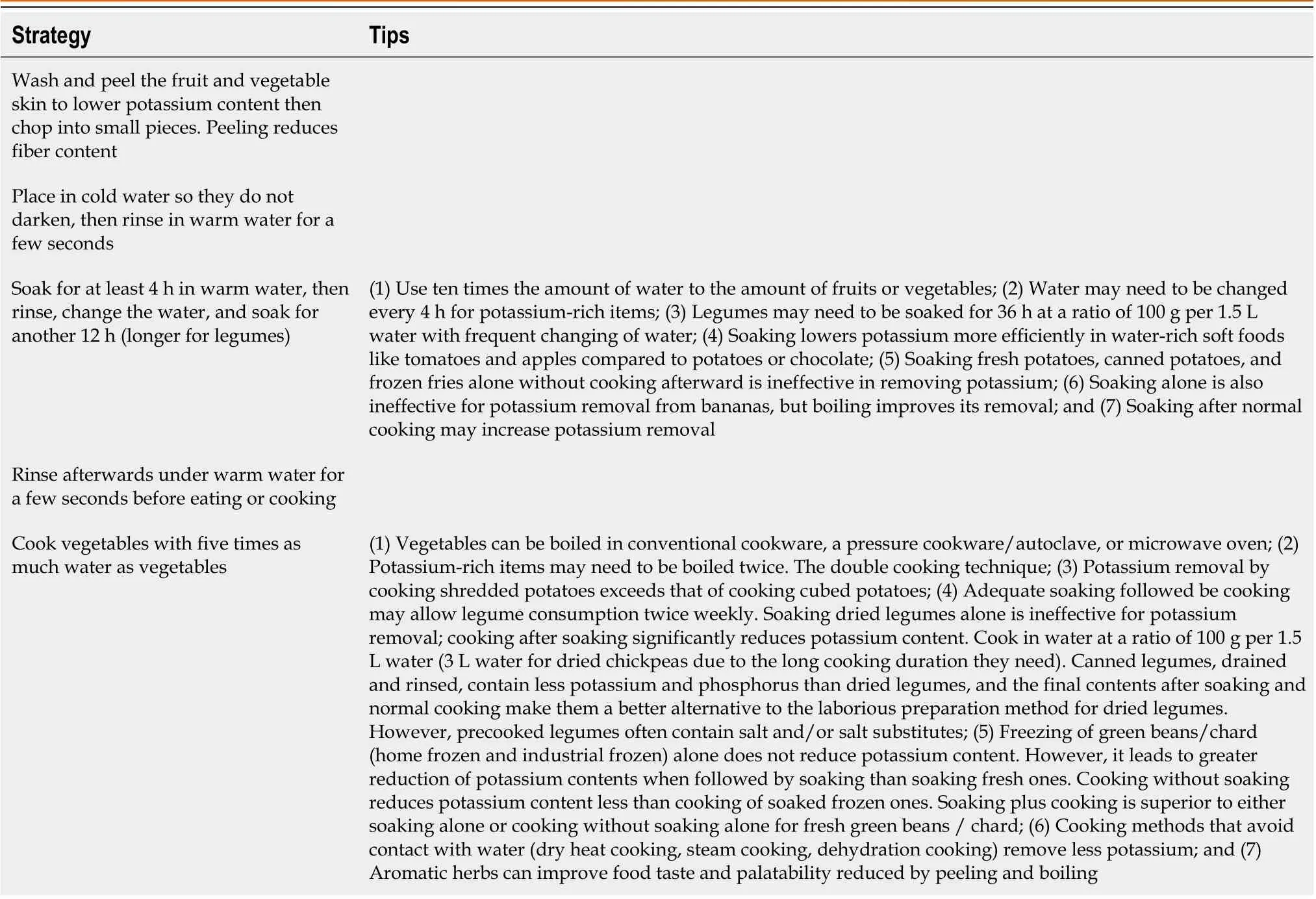

A stepwise reduction in potassium intake is advised to ensure a balanced intake of fresh fruits and vegetables and fiberby patients with advanced CKD who are not prone to hyperkalemia[5,16].Table 3 summarizes several strategies that should be implemented to minimize the risk of hyperkalemia before restricting potassium intake.Table 4 describes the steps to gradually restrict potassium intake and to minimize the impact of this approach on the patient.Table 5 describes cooking methods that can help reduce potassium levels in fruits and vegetables to increase the number of permissible food items.

Table 2 Recommended potassium intake for adult patients with chronic kidney disease

Table 3 Strategies to reduce the risk of hyperkalemia in chronic kidney disease before employing potassium dietary restriction

Table 4 Strategies to gradually introduce a mild potassium-restrictive dietary plan

Information compiled from references[1,2,5,12,15,16,19,20,31,45-50,52].

Table 5 Food preparation methods to help lower food contents of potassium and ease restriction intensity

CONCLUSION

Although potassium intake restriction is the standard of care in advanced CKD and ESKD, there is a need for the reevaluation of this approach in CKD patients who do not have hyperkalemia.There are health benefits of a plant-based,potassium-rich diet, and it is difficult to implement a low-potassium diet.There is scarce and inconsistent data attributed to dietary potassium in patients with CKD, and the risk of hyperkalemia may have been overstated.Under the supervision of a skilled dietician, the list of permissible food items may be gradually expanded by introducing unprocessed and properly prepared plant-based foods, especially those with a low potassium to fiber ratio, to improve the quality of food intake.Further research on moderate gradual liberalization of potassium intake in patients with CKD is certainly warranted.

FOOTNOTES

Author contributions:The sole author of the manuscript.

Conflict-of-interest statement:There are no conflicts of interest to report.

Open-Access:This article is an open-access article that was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers.It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution NonCommercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial.See: https://creativecommons.org/Licenses/by-nc/4.0/

Country/Territory of origin:Kuwait

ORCID number:Ali AlSahow 0000-0001-8081-3244.

S-Editor:Ma YJ

L-Editor:A

P-Editor:Ma YJ

World Journal of Nephrology2023年4期

World Journal of Nephrology2023年4期

- World Journal of Nephrology的其它文章

- Immunoglobulin A vasculitis nephritis: Current understanding of pathogenesis and treatment

- Transcending boundaries: Unleashing the potential of multi-organ point-of-care ultrasound in acute kidney injury

- Role of simulation in kidney stone disease: A systematic review of literature trends in the 26 years