Historical development of karst evergreen broadleaved forests in East Asia has shaped the evolution of a hemiparasitic genus Brandisia(Orobanchaceae)

Zhe Chen ,Zhuo Zhou ,Ze-Min Guo ,b ,Truong Vn Do ,Hng Sun ,* ,Yng Niu ,**

a CAS Key Laboratory for Plant Diversity and Biogeography of East Asia, Kunming Institute of Botany, Chinese Academy of Sciences,132 Lanhei Road,Kunming 650201, Yunnan, China

b University of Chinese Academy of Sciences, Beijing 100049, China

c Vietnam National Museum of Nature, Vietnam Academy of Science and Technology,18 Hoang Quoc Viet, Cau Giay 10000, Hanoi, Vietnam

d Graduate University of Science and Technology, Vietnam Academy of Science and Technology,18 Hoang Quoc Viet, Cau Giay 10000, Hanoi, Vietnam

Keywords:Biogeography Brandisia Evergreen broadleaved forests (EBLFs)Karst Orobanchaceae Phylogeny

ABSTRACT Brandisia is a shrubby genus of about eight species distributed basically in East Asian evergreen broadleaved forests (EBLFs),with distribution centers in the karst regions of Yunnan,Guizhou,and Guangxi in southwestern China.Based on the hemiparasitic and more or less liana habits of this genus,we hypothesized that its evolution and distribution were shaped by the development of EBLFs there.To test our hypothesis,the most comprehensive phylogenies of Brandisia hitherto were constructed based on plastome and nuclear loci (nrDNA,PHYA and PHYB);then divergence time and ancestral areas were inferred using the combined nuclear loci dataset.Phylogenetic analyses reconfirmed that Brandisia is a member of Orobanchaceae,with unstable placements caused by nuclear-plastid incongruences.Within Brandisia,three major clades were well supported,corresponding to the three subgenera based on morphology.Brandisia was inferred to have originated in the early Oligocene (32.69 Mya) in the Eastern Himalayas-SW China,followed by diversification in the early Miocene (19.45 Mya) in karst EBLFs.The differentiation dates of Brandisia were consistent with the origin of keystone species of EBLFs in this region (e.g.,Fagaceae,Lauraceae,Theaceae,and Magnoliaceae) and the colonization of other characteristic groups(e.g.,Gesneriaceae and Mahonia).These findings indicate that the distribution and evolution of Brandisia were facilitated by the rise of the karst EBLFs in East Asia.In addition,the woody and parasitic habits,and pollination characteristics of Brandisia may also be the important factors affecting its speciation and dispersal.

1.Introduction

East Asian subtropical/warm-temperate evergreen broadleaved forests(EBLFs) landscapes are prominent,as regions at the similar latitudes (23-35°N) are largely covered by desert or semi-desert(Tang,2015;Song and Da,2016).This zonal vegetation develops under a monsoon climate and harbours high biodiversity and endemism,and East Asia was considered a very important center of speciation and evolution,and attracts much attention consequently(Wu,1980;Axelrod et al.,1996;Wu and Wu,1996;Song and Da,2016;Chen et al.,2018).

The East and Southeast Asian flora has been suggested to be ancient (Takhtajan,1969).Paleovegetational reconstruction in South China clued that EBLFs existed there during the Miocene(Zhao et al.,2004;Jacques et al.,2011;Sun et al.,2011).In addition,molecular phylogenetic analyses on the dominant taxa (such as Fagaceae,Lauraceae,Theaceae,and Magnoliaceae) in this region also suggested that East Asian EBLFs were established mainly around the Oligocene-Miocene(O-M)boundary,possibly affected by the formation and development of the Asian monsoon(Yu et al.,2017;Chen et al.,2018;Deng et al.,2018;Hai et al.,2022;Xiao et al.,2022).However,research on epiphytic orchids (DendrobiumSw.)indicated that EBLFs may have arisen in mainland Asia since the beginning of the Oligocene (Xiang et al.,2016),which broadly agrees with U-Pb zircon dating of fossil-bearing strata(Tian et al.,2021).

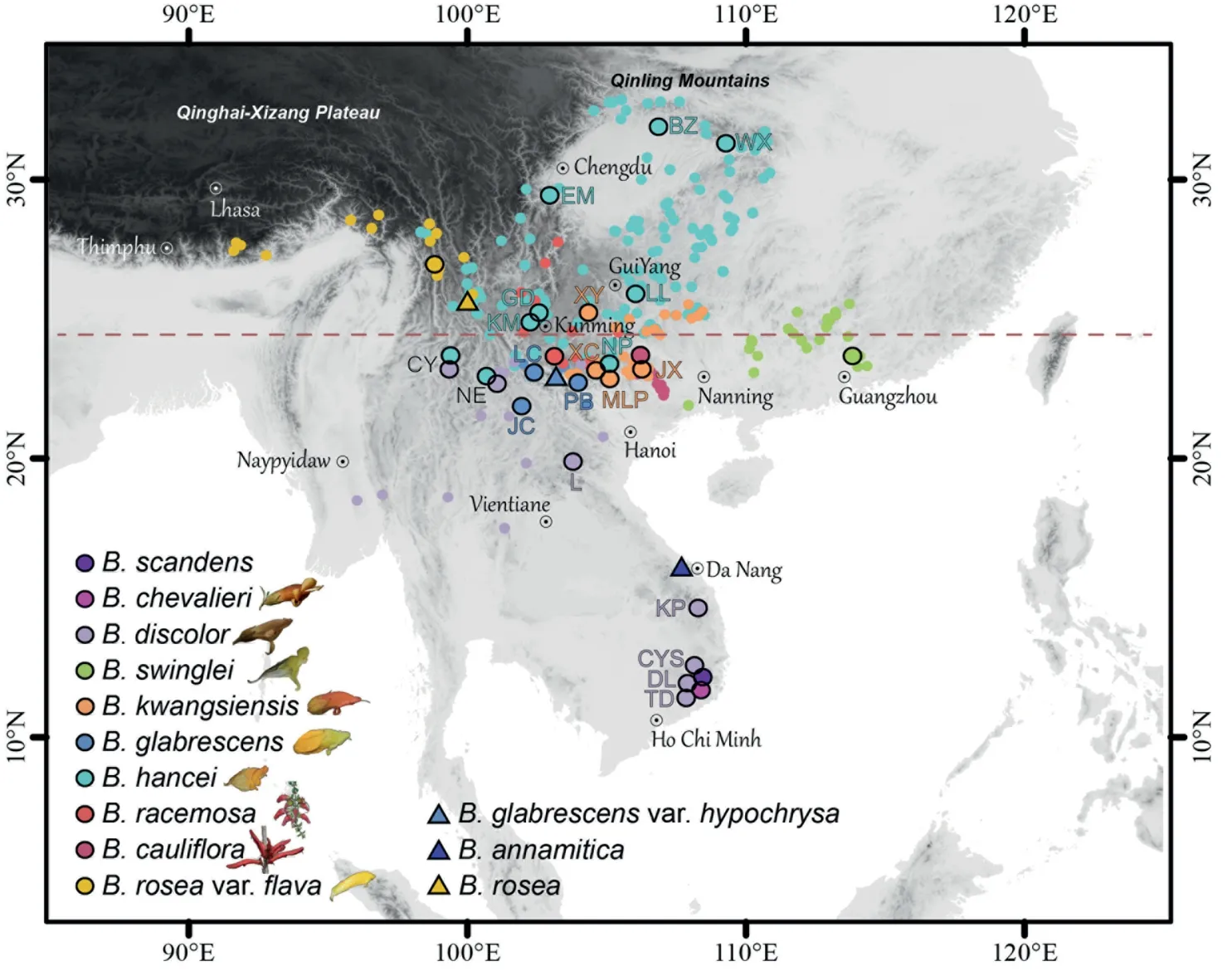

BrandisiaHook.f.&Thomson is one of the representative undergrowth of East Asian subtropical/warm-temperate EBLFs (between 21-30°N and 97-141°E;Figs.1 and 2;Song and Da,2016).Brandisiaspecies are shrubs with a more or less liana habit that inhabit mountainous areas at low-medium elevations(500-3000 m),living under forests,along forest edges,mountain slopes,trails and riverbanks.MostBrandisiaspecies are endemic to East Asia,althoughBrandisia discolorHook.f.&Thomson can extend into tropical Southeast Asia.The current distribution center is in karst areas in southwestern China (around the Tropic of Cancer,23.5°N;Fig.2;Li,1947;Hong et al.,1998).The continuous karst regions in southwestern China cover a great area(ca.21-30°N and 100-110°E;Ford and Williams,2007;Hollingsworth,2009;Wang et al.,2019),which are characterized by diverse environments and great species diversity and endemism (Davis et al.,1995;Zhu,2007).Evidence from phylogeny and paleobotany suggested that the karst vegetation formed after the O-M boundary (Li et al.,2022a,2022b) or even much earlier (at the early Oligocene;Huang et al.,2018;Tian et al.,2021).Moreover,Brandisiais hemiparasitic (Nickrent,2020),and may need hosts at least in some phases of its lifecycle.Considering the distribution and hemiparasitic habit ofBrandisia,it can be considered characteristic of East Asian EBLFs.Therefore,we hypothesized that its evolution and dispersal should be shaped by the historical dynamics of the development of EBLFs in East Asia,especially in the karst regions.Clear taxonomic and phylogenetic contexts are the essential prerequisites for verifying our hypothesis,which have not been fully resolved.

Brandisiawas originally described by Hooker and Thomson(1864),and was “approximately determined” as a member of Scrophulariaceae sensu lato due to the numerous ovules.However,Li(1947)proposed that transferringBrandisia(together with closerelated taxaPaulowniaSiebold &Zucc.andWightiaWall.) into Bignoniaceae was more appropriate than retaining it in Scrophulariaceae.Currently,there are 13 taxa(11 species and two varieties)inBrandisia.Eight species and two varieties can be found in China,while three are endemic to Vietnam (Bonati,1924;Tsoong and Lu,1979;Hong et al.,1998;Pham,2000).Over the last two decades,phylogenetic studies have shed new light on the position ofBrandisia.Studies based on nuclear loci,plastid loci and plastid genomes have revealed thatBrandisiais a member of Orobanchaceae(Oxelman et al.,2005;Zhou et al.,2014;Xia et al.,2019;Li et al.,2021a).However,the exact placement ofBrandisiawithin Orobanchaceae varies among different molecular data.Studies based on nuclear coding gene phytochrome A (PHYA;Bennett and Mathews,2006),combined loci (nuclear ribosomal internal transcribed spacer/ITS,phytochrome A/PHYA and phytochrome B/PHYB;plastidmatKandrps2;McNeal et al.,2013),and ITS data(Yu et al.,2018) supported thatBrandisiais sister to the major clade of hemiparasites (Rhinantheae,Buchnereae,Pedicularideae,andPterygiellaOliv.).However,the results of plastid data showed incongruence,as phylogenies derived from plastome data supported Rhinantheae is sister toBrandisia(Xia et al.,2019;Li et al.,2021a).

In this study,we intended to investigate the evolution ofBrandisiaand its potential relationship with East Asian EBLFs.We first conducted phylogenetic analyses based on plastome and nuclear sequences,exploring the position ofBrandisiaand clarifying the species relationships within this genus.We then inferred divergence times and the biogeographic origin ofBrandisia,which was used to explore its evolution and dispersal history.

2.Materials and methods

2.1.Taxa sampling, DNA extraction and sequencing

ElevenBrandisiataxa were used in this study (with 57 accessions;Table S1),including a potential hybrid population betweenB.discolorandB.hancei.Three of 13Brandisiataxa(Brandisia roseavar.rosea, B.glabrescensvar.hypochrysaandB.annamitica) were unavailable due to unclear locality records or habitat destruction.For phylogenetic analyses,40 taxa of major lineages in Orobanchaceae were used.Paulownia tomentosa(Thunb.) Steud.was chosen as the outgroup based on previous studies(McNeal et al.,2013;Xia et al.,2019;Li et al.,2021a).All the DNA sequences butBrandisiawere obtained from GenBank (Table S2).

ForBrandisia,total genomic DNA was extracted from silica geldried leaves using the Plant Genomic DNA Kit DP305 (Tiangen Biotech,Beijing,China).DNA was fragmented with a focused ultrasonicator (Covaris) to construct a library.Paired-end reads of 150 bp were sequenced on the Illumina HiSeq 2000 platform at Novogene Co.(Beijing,China),generating 1.02-3.95 Gb of clean data (Table S1).Three samples ofBrandisia kwangsiensis(MLP,XC and XY;Fig.2,Table S1) were derived from herbarium specimens;the library construction followed a strategy customized for specimen materials (Zeng et al.,2018).

2.2.Sequence assembly and annotation

Clean sequencing data was analysed using the GetOrganelle pipeline(Jin et al.,2020)to assemble and select plastid genome and nuclear loci(nuclear ribosomal DNA(nrDNA),PHYA and PHYB).For the plastomes and nrDNA,the defaulted seed sequences of embryophyta plastome and plant nuclear ribosomal RNA were used,respectively.For PHYA and PHYB,sequences of Orobanchaceae from GenBank were used to build the seed files manually.The assembled plastomes were first annotated by PGA software (Qu et al.,2019) using the plastome ofPaulownia tomentosa(NC_031436) as the reference and then manually checked and adjusted in Geneious 9.0.2.Contigs of nuclear loci were annotated in Geneious 9.0.2 using ribosomal DNA ofP.tomentosa(KP718625),PHYA ofSolanum lycopersicumL.(NM_001247561),and PHYB ofS.lycopersicum(NM_001306202) as references.

2.3.Phylogenetic datasets construction and alignment

Based on the plastid genome and nuclear loci,seven datasets were constructed for phylogenetic analyses:1)complete plastome sequences with the removal of inverted repeat B (IRb);2) the concatenation of 81 plastid protein-coding genes (CDSs);3) the nuclear ribosomal DNA sequences (nrDNA);4) PHYA DNA sequences;5)and 6)two copies of PHYB DNA sequences(PHYB_1 and PHYB_2);and 7) the combined sequences of nuclear loci (nrDNA,PHYA,PHYB_1 and PHYB_2).Datasets were aligned using MAFFT v.7.308 in Geneious 9.0.2 or MAFFT v.7 online.Because the plastomes of most taxa in Orobanchaceae have undergone serious rearrangement,we adjusted these plastomes prior to alignment using the online software Mulan (https://mulan.dcode.org/).Plastomes ofBrandisia, Paulownia tomentosa, Triaenophora shennongjiaensisX.D.Li,Y.Y.Zan&J.Q.Li,RehmanniaLibosch.ex Fisch.&C.A.Mey andLindenbergia philippensis(Cham.&Schltdl.)Benth.showed little rearrangement,thus,they were not processed in Mulan.

2.4.Phylogenetic analyses

For each dataset above,maximum likelihood(ML)analysis was conducted using RAxML-NG (1.0.0-master;Kozlov et al.,2019).Support values for nodes and clades were estimated through 1000 bootstrap replicates.For complete plastome sequences (dataset 1)and combined nuclear loci sequences (dataset 7),Bayesian inference (BI) analysis was also conducted using MrBayes (3.2.7a;Ronquist et al.,2012).Markov chain Monte Carlo (MCMC) analysis was conducted using two independent runs,each having four incrementally heated chains.A total of 5,000,000 and 10,000,000 generations of MCMC chains were run for dataset 1 and dataset 7,respectively.The first 25%of tree samples were discarded as burnin,and the remaining samples were used to generate a majorityrule consensus tree.To find the best substitution model for nucleotide sequences,ModelTest-NG (0.1.6;Darriba et al.,2020),with the corrected Akaike information criterion (AICc),was used.For dataset 7,nuclear loci were treated as different partitions;the GTR+I+G model was the best model for each nuclear locus.RAxML-NG,MrBayes and ModelTest-NG analyses mentioned above were carried out on the CIPRES platform(Miller et al.,2010).Trees were visualized using FigTree v.1.4.4 (http://tree.bio.ed.ac.uk/software/figtree/).

2.5.Molecular dating

Because we believe that the combined sequences of nuclear loci(dataset 7) generated the true species tree ofBrandisiaspecies(detailed in the discussion),we used this dataset to estimate divergence times.BEAST(v.2.6.3;Bouckaert et al.,2014)was used at CIPRES.Because no reliable fossils have been found in Orobanchaceae,a secondary calibration strategy was adopted.We used two secondary calibration points derived from previous work involving Lamiales,which incorporated four fossils(Yu et al.,2018).The stem and crown ages of Orobanchaceae were set as 56.23±10 and 54.56 ± 10 Mya with normal models,respectively.We set the nucleotide substitution model to GTR+I+Γ (selected by ModelTest-NG).We used an uncorrelated lognormal relaxed molecular clock model and the Yule speciation model for tree priors.The MCMC ran 100,000,000 generations and sampled every 1000 generations.The first 3000 generations were removed as “Preburn-in”.The output log file was then checked for convergence of the chains using Tracer v.1.7 to confirm that the ESSs of all parameters were more than 200.TreeAnnotator v.1.7.5 was used to obtain the maximum clade credibility(MCC)tree with the posterior probability limit set to 0.5.The initial 10% of the trees were discarded as burn-in.

2.6.Estimation of ancestral areas

To infer ancestral area,we used the S-DIVA(Statistical dispersalvicariance analysis) and BBM (Bayesian binary MCMC) methods implemented in RASP 4.2 (Reconstruct Ancestral State in Phylogenies;Yu et al.,2015,2020).The 90,001 trees(the first 10,000 trees were discarded)from BEAST analysis above were used as input,and onlyBrandisiaspecies were selected for analysis.For S-DIVA analysis,1000 trees were sampled randomly,the number of maximum areas was set as 2,and only dispersals between adjacent areas were allowed.For BBM analysis,the consensus tree derived from the 90,001 tree inputs was used.MCMC chains were run simultaneously for 500,000 generations and sampled every 100 generations.Fixed JC+G (Jukes-Cantor+Gamma) was used for BBM analysis with null root distribution.The number of maximum areas was set to 1.Six distribution areas were set based on the distribution ofBrandisia,the floristic regions of China proposed by Wu and Wu (1996;based on the floral composition and vegetation types),topography and the distribution of karst in China and SE Asia(Sweeting,1995;Hollingsworth,2009).They were A,Eastern Himalayas;B,Yunnan Plateau (and adjacent areas of SW Sichuan and W Guangxi);C,Core Karst in SW China(SE Yunnan,N Guizhou,W Guangxi;also including a part of N Vietnam);D,Southern China;E,Central China;F,Indochina(the wide area south of the Red River,including SW Yunnan,Myanmar,Thailand,Laos,and Vietnam).

3.Results

3.1.Assembly of plastomes and nuclear sequence fractions

Complete plastomes were assembled for most of theBrandisiasamples,except for three samples,each with one gap located in the small single copy region (Table S1).The plastomes ofBrandisiashowed a typical quadripartite structure (Fig.S1),with large and small single copy (LSC and SSC,respectively) regions separated by two large inverted repeats (IRs).Three of the fiveB.kwangsiensissamples (MLP,XC and XY) showed plastomes much longer(159,382-159,469 bp)than the otherBrandisiasamples due to the expansions of their IRs (Fig.S2).For the remainingBrandisiasamples,total length ranged from 154,580(B.hanceiNP)to 155,391 bp(B.swinglei).Gene contents included 115 unique genes for each sample,including 81 protein-coding genes(CDSs),30 transfer RNA(tRNA) genes,and four ribosomal RNA (rRNA) genes.Except forB.roseavar.flava,the slight expansions of the IRs toward the LSC led to the duplication of therps19gene in most samples and the duplication of therpl22gene further inB.hanceifrom BZ(Bazhong,Sichuan;Fig.S2).No other rearrangements or pseudogenes were found.

The nuclear ribosomal DNA(nrDNA)sequences were assembled for all the samples,which covered 18S,ITS1 (internal transcribed spacer),5.8S,ITS2,28S,and partial IGS(intergenic spacer).For IGSs,regions with good alignment(mainly the ETS(external transcribed spacer)regions)were used for phylogenetic analysis.Nuclear genes of PHYA and PHYB were assembled in some of our samples and often contained several contigs that composed partial sequences.Our results showed that PHYA was probably a single-copy gene inBrandisia.However,PHYB was probably a double-copy gene,as our assembled contigs showed different similarities to the two PHYB copies cloned in Pedicularideae in a previous study (McNeal et al.,2013).In our study,the two PHYB copies were named PHYB_1 and PHYB_2.The lengths of nrDNA,PHYA,PHYB_1 and PHYB_2 used are provided in Table S1.

3.2.Phylogeny construction

Information on sequence length,parsimony-informative (PI)sites and model selection of the seven aligned datasets are shown in Table S3.Phylogenies based on whole plastomes (with IRbremoved;dataset 1) and CDS datasets (dataset 2) were consistent with each other (Figs.3 and S3).The monophyly ofBrandisiawas well supported,and it was sister to Rhinantheae.Brandisiawas divided into three clades.Clade I contained onlyB.roseavar.flava.Clade II containedB.racemosaandB.cauliflora.The remaining species were placed in Clade III,within whichB.glabrescensandB.hanceiclustered in a clade that was sister to all other taxa.

In addition,Brandisia discolorwas divided into two clades,one from China and the other from Laos and Vietnam.Brandisia scandensandB.chevalieriwere embedded inB.discolorfrom Laos and Vietnam.For the four potential hybrid samples betweenB.discolorandB.hancei,three were embedded withinB.discolorfrom China,and the other one was nested withinB.hancei.

The phylogenies derived from the individual dataset of the four nuclear loci (nrDNA,PHYA,PHYB_1 and PHYB_2;dataset 3-6)could hardly resolve the position ofBrandisiain Orobanchaceae,and the relationships withinBrandisiawere generally not strongly supported (Figs.S4-S7).However,the topologies of the major clades withinBrandisiawere congruent with each other,except thatB.swingleiandB.kwangsiensisformed a sister group with great support (BS=100) based on PHYB_1 (Fig.S6).

The combined dataset of four nuclear loci(dataset 7)generated a phylogeny with better resolution (Fig.4).The monophyly ofBrandisiawas well supported,and was sister to a clade containing Rhinantheae,Buchnereae,Pedicularideae andPterygiella(BS/PP=66/1).Brandisiawas divided into three clades,among which Clades I and II were identical to the results from the plastid datasets,while several major differences occurred in Clade III.First,B.hanceiwas sister to the other taxa in Clade III but not onlyB.glabrescens.Second,samples ofB.discolorclustered together(withB.scandensandB.chevalieriembedded in),and samples ofB.discolorfrom Vietnam were separate from those from China and Laos.Third,all the potential hybrid individuals(betweenB.discolorandB.hancei) were nested withinB.hancei.

3.3.Divergence-time and ancestral areas estimation

BEAST analysis showed thatBrandisiaand its sister diverged in the early Oligocene (32.69 Mya,95% HPD=21.66-44.39),and the diversification ofBrandisiawas dated to the early Miocene (19.45 Mya,95% HPD=10.28-31.22).Clades II and III diverged 15.8 Mya(95%HPD=8.51-25.55),and their diversifications were dated back to 7.16 (95% HPD=2.19-15.62) and 12.33 Mya (95%HPD=6.89-19.5),respectively(Fig.5).The exact values for the two calibrations and 8 annotated nodes are detailed in Table 1.

Table 1 Partial lineage divergence times estimated by BEAST.Nodes correspond to those labelled in Fig.6.

Brandisiais mainly distributed in southern China,Vietnam,Laos,Thailand,and India (Assam),with a current distribution center around the karst regions of Yunnan-Guizhou-Guangxi (Fig.2).SDIVA and BBM analyses inferred thatBrandisiaoriginated in the Yunnan Plateau and Eastern Himalayas (BA) and the Yunnan Plateau and Core Karst in SW China(BC),respectively(Fig.6).These results indicate this genus probably originated in the Eastern Himalayas-SW China,formed distribution center in the karst region,and dispersed eastwards into the evergreen broadleaved forests in South China(Fig.6).In addition,B.hanceiandB.discolorare the two most widely distributed species in this genus.B.hanceiextends northwards up to the southern margin of the Qinling Mountains (ca.33°N),whereasB.discolorreaches southern Vietnam (Da Lat city,Lam Dong province,ca.12°N;Fig.2).

4.Discussion

4.1.Conservatism of Brandisia plastomes

Orobanchaceae is a diverse family where parasitic herbs are predominant.Except for several autotrophic taxa (Triaenophora(Hook.f.) Soler.,RehmanniaandLindenbergiaLehm.),plastome rearrangements (including IR loss/expansion/contraction,gene order change,pseudogenization and loss of genes) are common across the whole family,which reflects the loss of pressure on the plastome in their evolutionary progress (Krause,2008;Wicke et al.,2013;Cusimano and Wicke,2016;Frailey et al.,2018).It is believed that there is a single origin of parasitism in Orobanchaceae,followed by several independent evolutions of holoparasitism (Young et al.,1999;Bennett and Mathews,2006;McNeal et al.,2013).Brandisiais a relatively later-derived genus,and is sister to the major hemiparasites in Orobanchaceae(detailed below).In addition,although certain hosts are unknown,haustoria has been discovered in the roots ofBrandisia(Personal communication with Dr.Wen-Bin Yu).Therefore,it is reasonable to expect hemiparasitic habits inBrandisia.However,the plastomes ofBrandisiaare complete and conventional,with full gene contents and merely a slight expansion of IRs (except for three samples ofB.kwangsiensis),which are highly similar to the nonparasitic taxa in Orobanchaceae.Brandisiais one of the few shrubby genera (such asAlectraThunb.andXylocalyxBalf.f.) in Orobanchaceae and has the largest size(B.discolorcan reach 3 m high;field observation).This bushing habit,which requires high photosynthetic productivity for development,probably explains the constant selection on plastomes and consequently their conservatism.Brandisiapresumably relies less on its host,perhaps only in its early stage (such as seedling),which requires further study in the future.

4.2.Phylogenies of Orobanchaceae and Brandisia

Brandisiais a unique genus whose taxonomic placement has been arguable since its first description.Morphologically,it shows affinity to several families (such as Scrophulariaceae and Bignoniaceae;Hooker and Thomson,1864;Li,1947).The woody generaPaulowniaandWightiawere deemed close toBrandisiaand showed similarities in capsules and seeds (Hooker and Thomson,1864).However,phylogenetic evidence supports the placement ofBrandisiain Orobanchaceae,andPaulowniaas an outgroup of Orobanchaceae (Wightia,however,is relatively more distant;Olmstead et al.,2001;Xia et al.,2019;Li et al.,2021a).The exact position ofBrandisiain Orobanchaceae has been unstable because phylogenetic research based on different(nuclear vs.plastid)sequence data has reached discordant conclusions (McNeal et al.,2013;Yu et al.,2018;Xia et al.,2019).Our study shows a similar incongruence between nuclear-plastid data.Our plastome phylogeny placed Rhinantheae as sister toBrandisia(Fig.4),which agrees with previous studies by Xia et al.(2019) and Li et al.(2021a);in contrast,our nuclear phylogeny placed the major clade of hemiparasites(Rhinantheae,Buchnereae,Pedicularideae,andPterygiella)sister toBrandisia(Fig.5),which agrees with previous studies by Bennett and Mathews (2006),McNeal et al.(2013),and Yu et al.(2018).In addition,Pterygiella(Xia et al.,2019) or thePterygiellagroup(Pterygiella,thePhtheirospermumBunge ex Fisch.&C.A.Mey.complex andXizangiaD.Y.Hong;Yu et al.,2018) were resolved as sister toBrandisiafurther based on plastid locus;and morphological affinity betweenBrandisiaandPterygiellahave been noted by Xia et al.(2019).Currently,the position ofBrandisiain Orobanchaceae is still unresolved and requires further study.This could be essential to understanding other important matters in this highly diverse family,such as the evolution of parasitism habits.

The three clades ofBrandisiain both plastome and nuclear phylogenies (Figs.3 and 4) correspond to the three subgenera proposed by Li (1947) based on morphological traits.Clade I(B.roseaonly)corresponds to subg.Rhodobrandisia,which has twolobed calyces.Clade II(B.caulifloraandB.racemosa)corresponds to subg.Coccineabotrys,which has inflorescences with red corollas.Clade III (B.hancei, B.glabrescens, B.kwangsiensis, B.swingleiandB.discolor(includingB.chevalieriandB.scandens)) corresponds to subg.Eubrandisia(should be revised as subg.Brandisia;autonym;Turland et al.,2018),which has solitary or paired axillary flowers and five-lobed calyces.B.cauliflorawas described later and thus not included in Li's study (1947).Owing to its red inflorescence,B.cauliflorashould be a member of subg.Coccineabotrys.B.laetevirenswas accepted as a distinct species and was placed intoB.subg.Brandisiaby Li(1947).However,it was treated as a synonym ofB.hanceiinFlora Reipublicae Popularis Sinicae(FRPS;Tsoong and Lu,1979) andFlora of China(FOC;Hong et al.,1998) later.After examining the type specimens (A00056851,A;MO-503773,MO;K000961210,K;and US00122408,US) and the protologue ofB.laetevirens,we found this“species”showed high similarity to the potential hybrid individuals we found,as it showed intermediate features betweenB.hanceiandB.discolor.B.laetevirensdiffers fromB.hanceiby larger leaf with longer petiole and less cordate base,and a narrower calyx;and it differs fromB.discolorby its shorter petiole and larger calyces.Therefore,B.laetevirensis presumably a hybrid betweenB.discolorandB.hancei.The potential hybrid individuals we found (betweenB.discolorandB.hancei) clustered withB.discolororB.hanceiin the plastid phylogeny (Fig.4),whereas in the nuclear phylogeny they only clustered withB.hancei,which possibly indicates different directions of hybridization further,if the plastome is maternally inherited.In the contact community ofB.hanceiandB.discolorwe found,their flowering phenologies overlap highly (in Jan.-Feb.) and both provide copious nectar to avian pollinators.In addition,birds seemed not to differentiate betweenB.hancei,B.discolorand their hybrids in the field(for their similar reward;Chen et al.,unpublished data).These factors make hybridization and backcross possible.

Phylogenetically,the positions and compositions of Clade I and Clade II withinBrandisiawere robust,whereas nuclear-plastid incongruences occurred in Clade III (Figs.3 and 4).These results indicate different evolutionary trajectories of plastome and nuclear loci,which may be attributed to incomplete lineage sorting and hybridization(Rieseberg and Soltis,1991;Jakob and Blattner,2006;Pelser et al.,2010).The nuclear phylogeny possibly revealed the true species tree ofBrandisiafor two reasons.First,the plastome phylogeny separatedB.discolorinto two clades that were not sisters to each other (Fig.3).This molecular result conflicts with morphological evidence.In contrast,in the nuclear phylogeny,all the samples ofB.discolorformed a monophyletic clade (Fig.4).Second,plastomes are primarily maternally inherited,which illuminates only half of the parentage.Therefore,plastome phylogenies may not reveal hybrid history correctly (Small et al.,2004).Consequently,the phylogeny based on nuclear loci (biparentally inherited) in our study may be better at illuminating species relationships,if hybridization occurred inBrandisia.

Brandisia chevalieriandB.scandenswere nested withinB.discolorclade,andB.chevalieriwas not even monophyletic(Figs.3 and 4).Morphologically,B.discolor, B.chevalieriandB.scandensshowed great similarity and can hardly be distinguished(Fig.1).They all have ovate-lanceolate to narrowly lanceolate blades with irregularly undulate margins,which are glabrescent adaxially but densely gray to tawny tomentose abaxially and turn brown-black when dry (Fig.1K-L).They all flower in winter-spring with brown-red corollas and small calyces.Therefore,both molecular and morphological evidence support the treatment ofB.chevalieri, B.scandensandB.discoloras a single species.AsB.discolorwas validly published earlier thanB.chevalieriandB.scandens,the latter two should be synonyms ofB.discolor.

Fig.1. Photos of Brandisia.A,B.rosea var.flava;B,B.cauliflora;C,B.racemosa;D,B.hancei;E,B.glabrescens;F,B.kwangsiensis;G,B.swinglei;H,B.discolor.I,Hybrid of B.hancei and B.discolor;J1-J2,Flower,corolla and leaves of B.hancei,B.discolor and their hybird.K1-K2,Flower,leaves,and fruits of B.chevalieri;L1-L2,Branch,leaves and fruits of B.scandens.

4.3.Origin and coevolution of Brandisia with karst evergreen broadleaved forest

Brandisiais a characteristic component of karst evergreen broadleaved forests (EBLFs) in E Asia for its distribution,and hemiparasitic and liana characteristics.Most species in this genus inhabit East Asian EBLF communities (ca.23-39°N),especially in the karst regions in southern China and northern Vietnam nearby(Fig.2).They usually grow under forests,along forest edges,mountain slopes,trails and riverbanks.In addition,the hemiparasitic habit ofBrandisiameans certain host plants in their communities are essential for their lifecycles (Nickrent,2020),indicating thatBrandisiaspecies are highly dependent on the EBLFs.

Fig.2. Distribution and sampling of Brandisia.Points in different colour show species distribution based on specimen records and our fieldwork.The large points with black outlines show our sampling sites.Letters indicate populations,which are also used in Figs.3-5.Details regarding collection vouchers can be found in Table S1.Triangles indicate places where species were recorded by specimens but not found personally.The red dashed line shows the Tropic of Cancer at 23.5°N.

Fig.3. Strict consensus tree derived from Bayesian inference of complete plastome.The values above and under the branches show posterior probability(PP)and bootstrap support(BS),respectively.The topology of Brandisia with short branch lengths is shown on the right.The bottom bar shows the number of substitutions per site.

Fig.4. Strict consensus tree derived from Bayesian inference of combined datasets of four nuclear loci (3S/ITS,PHYA,PHYB_1 and PHYB_2).The values above and under the branches show posterior probability (PP) and bootstrap support (BS),respectively.

Fig.5. The maximum clade credibility(MCC) tree derived from BEAST based on combined datasets of four nuclear markers(3S/ITS,PHYA,PHYB_1 and PHYB_2) for Brandisia and other related taxa.The blue bars show 95%higher posterior densities(HPD).Two calibrated(red)and 8 key stem/crown nodes(black)are annotated by letters and/or numbers.Six diagnostic characteristics are provided.Trait 1,calyx bilabiate with two lobes(solid circles);calyx with five lobes(open circles).Trait 2,raceme(solid triangles);single flower(open triangles).Trait 3,raceme borne on main stem,compact (solid inverted triangles);raceme terminal,long (open inverted triangles).Trait 4,flower in summer (-autumn) (solid squares);flower in winter(-spring)(open squares).Trait 5,blade base subcordate,margin revolute(solid diamonds);blade base cuneate to subrounded,margin not revolute(open diamonds).Trait 6,calyx big,vivid yellow (solid stars);calyx small to medium,gray or brown (open stars).

We estimate thatBrandisiaoriginated in the early Oligocene(32.69 Mya) in SW China (from the Eastern Himalayas through Yunnan Plateau to the core karst areas in SW China,ABC;Figs.5 and 6).The date ofBrandisiaorigin is consistent with that of the establishment of EBLFs in these regions (Xiang et al.,2016;Tian et al.,2021).However,the diversification ofBrandisiastarted only after the early Miocene (19.45 Mya).Specifically,it was after the Oligocene-Miocene (O-M) boundary (ca.23 Mya),when modern East Asian flora arose (Axelrod et al.,1996;Chen et al.,2018).In concert with the development of the Asian monsoon and the accompanying copious precipitation (especially the winter precipitation;Li et al.,2021b) in this region (Sun and Wang,2005;Lu and Guo,2014;But see e.g.Spicer,2017),many essential elements(Fagaceae,Lauraceae,Theaceae and Magnoliaceae) and characteristic components (such asMahoniaandOreocharis) of East Asian evergreen broadleaved forests originated or colonized around the O-M boundary and diversified from this time onwards (Yu et al.,2017;Chen et al.,2018,2020;Deng et al.,2018;Hai et al.,2022;Kong et al.,2022;Xiao et al.,2022).The establishment of E Asian EBLFs probably provided suitable habits and hosts forBrandisia.After its origin,Brandisiadid not spread widely,but concentrated in the core karst areas in SW China and nearby northern Vietnam,which may have been facilitated by the establishment of the karst flora and EBLFs in the early Miocene (Deng et al.,2018;Li et al.,2022a,2022b).

The karst area in subtropical East Asia is a biodiversity hotspot that harbours high plant diversity with numerous endemic species(Davis et al.,1995;Zhu,2007).Previous studies have suggested thatQuercussect.Ilex(Fagaceae) and the Old World gesneriads (Gesneriaceae)colonized the karst regions in southwestern China in the early Miocene(ca.20 and 22 Mya,respectively;Deng et al.,2018;Li et al.,2022b).A study on caves of karst areas in southern China also illustrates that species colonization occurred mainly after the O-M boundary,which was in concert with the establishment of EBLFs(Li et al.,2022a).Precipitation from the East Asia monsoon likely accelerated the dissolution of the limestone substrate and deeply influenced the development of the karst region (Zhang,1980;Liu,1997;Li et al.,2007),which possibly created novel habitats for species diversification (Kong et al.,2017;Li et al.,2022a).In this process,newly disturbed and open habitats may have appeared,which may have contributed to the expansion and divergence ofBrandisia,sinceBrandisialikes relatively open habitats with more solar energy to afford the development of their large bodies.In addition,southwestern China and northern Vietnam possessed a long-term stable climate,which may have preserved species during the ice ages(Tang et al.,2018;Huang et al.,2022).This may partly explain why the karst area of southern China and northern Vietnam nearby are distribution centers ofBrandisia.There are threeBrandisiaspecies (B.swinglei, B.hanceiandB.discolor) whose distributions are no longer restricted to limestone habitats (Fig.2).B.swingleispread eastwards into the EBLFs in southern China.B.hanceiandB.discolorhave extended northwards and southwards into Central China and tropical Indochina,respectively.Their distribution patterns may indicate re-adaptation and occupation of novel habitats.

Considering the relatively early origin ofBrandisia,its species diversity is rather low (ca.eight species),and its distribution is relatively limited.This low diversity and narrow distribution may have several explanations.First,the long initialization period ofBrandisiamay be an overestimation caused by the possible extinction of its sister group.Brandisiais morphologically unique(Li,1947) and uncertain in phylogenetic placement (such as McNeal et al.,2013;Li et al.,2021a;and results in our study),and thus seems rather isolated(Nickrent,2020).This may be the result of the extinction of its close relatives,which consequently adds to the evolutionary time of their common ancestors to the origin ofBrandisia.Second,the early origin and lack of very close taxa indicate thatBrandisiais a relict genus.If so,the current distribution ofBrandisiamay be characteristic of a relic distribution.This scenario suggests that the possible original widespread distribution ofBrandisiaduring the Oligocene-Miocene retreated to the current distribution surrounding Sino-Himalayan regions.This may have coincided with the contraction of the distribution of EBLFs caused by historical climate change (Wolfe,1975;Kubitzki and Krutzsch,1996;Milne and Abbott,2002;Wang and Shu,2013).Third,the ecosystems of the karst EBLFs in southwestern China and northern Vietnam have been relatively stable since the Tertiary (Tang et al.,2018;Huang et al.,2022).Being restricted to stable and favourable environments may lead to low levels of speciation and dispersal because of limited resources and niches (Malohlava and Bocak,2010;Schluter,2016;Igea and Tanentzap,2020;Sun et al.,2020).This may explain why the karst regions possess fewer taxa with rapid radiations and diversity centers than do the Himalaya-Hengduan Mountains regions(Chen et al.,2018),and may be responsible for the observed low species diversity inBrandisia.Fourth,plants with woody habit are associated with lower diversification rates,possibly caused by greater longevity and longer generation time (Eriksson and Bremer,1992;Dodd et al.,1999).This may partly explain whyBrandisiahas lower diversity than that of other taxa in Orobanchaceae.In addition,the unitary growth form (shrub),hemiparasitic habit (may not afford their expansion to much different habitats with no proper host plants) and seeds with tiny wings(cannot support dispersal over long distances) possibly lead to niche conservatism and limited competition,which hinder the diversification and dispersal ofBrandisiafurther (Wiens and Donoghue,2004).Fifth,pollination is important for plant propagation,and pollinators can not only affect plant establishment and persistence(Sargent and Ackerly,2008),but also flower evolution and diversification(Dodd et al.,1999;Kay and Sargent,2009;Van der Niet et al.,2014).Brandisiais an ornithophilous genus (Chen et al.,unpublished data) whose distribution is consistent with its main avian pollinators (Nectariniidae,Dicaeidae,and Zosteropidae),which mainly occur at low latitudes where high productivity and stability of flower nectar resources can afford bird pollination (Proctor et al.,1996;Sekercioglu,2006).In addition,avian pollination is less developed in mainland East Asia(compared with the Americas,where hummingbirds and related flowers flourish;Fleming and Muchhala,2008;Funamoto,2019).Therefore,limited avian pollination niches in this region may not support a great diversification ofBrandisia.

5.Conclusions

In this study,we used both plastome and nuclear sequences to construct the most comprehensive phylogenies ofBrandisiato date.These results have updated our understanding of intrageneric relationships withinBrandisia.We found thatBrandisia,a typical hemiparasitic component of evergreen broadleaved forests(EBLFs),originated in the early Oligocene in the Eastern Himalayas-SW China and diversified in the early Miocene (19.45 Mya) mainly in E Asia karst EBLFs.Its evolution and distribution were shaped by the establishment of E Asia EBLFs,especially the historical development of karst forest ecosystems in southwestern China.In addition,some characteristics,such as hemiparasitism and pollination,are important factors in impacting plant evolution and dispersal,which deserve more attention in biogeography in the further.

Several fundamental issues regardingBrandisiahave not been fully resolved and require further study.First,the phylogenetic position ofBrandisiain Orobanchaceae was not ultimately determined.We recommend that future studies combine phylogenetic and morphological methods to resolve phylogenetic uncertainties withinBrandisia.Second,B.annamitica,which is endemic to Vietnam,was not examined in this study.This species is morphologically unique,having two staminodes.Further study is needed to clarify its phylogenetic and taxonomic position inBrandisia.Third,the extent of parasitism inBrandisiais currently unclear.Specific host plants have yet to be identified and our understanding of the lifecycle ofBrandisiais rather limited.Considering thatBrandisiais a unique (both morphologically and phylogenetically) genus in Orobanchaceae,further studies on this genus should provide us with a better understanding of the evolution of parasitism in Orobanchaceae and the relationship between parasitic and host plants.

Author contributions

H.S.and Y.N.conceived the study;Y.N.,Z.C.,T.V.D,Z.-M.G.and Z.Z.performed the fieldwork;Z.C.and Z.-M.G.analyzed the data;Z.C.drafted the manuscript;H.S.,Y.N.and Z.Z.revised the manuscript;all authors reviewed the manuscript and gave final approval for publication.

Declaration of competing interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Acknowledgements

We thank the Herbarium of Kunming Institute of Botany(KUN)for providing specimen samples and the Molecular Biology Experiment Center,Germplasm Bank of Wild Species in Southwest China(KIB)for sequencing these samples.We thank the Vietnam National Museum of Nature,Vietnam Academy of Science and Technology and the staff at National Parks and Natural Reserves for helping us in our fieldwork in Vietnam.This work was funded by the Key Projects of the Joint Fund of the National Natural Science Foundation of China (U1802232),the national youth talent support program,CAS "Light of West China" Program,Yunnan youth talent support program (YNWR-QNBJ-2018-183 to Y.N.),and Vietnam Academy of Science and Technology (UQÐTCB.06/22-23).

Appendix A.Supplementary data

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pld.2023.03.005.

- 植物多样性的其它文章

- Is intraspecific trait differentiation in Parthenium hysterophorus a consequence of hereditary factors and/or phenotypic plasticity?

- Convergent relationships between flower economics and hydraulic traits across aquatic and terrestrial herbaceous plants

- Integrative analysis of the metabolome and transcriptome reveals the potential mechanism of fruit flavor formation in wild hawthorn(Crataegus chungtienensis)

- Evidence of the oldest extant vascular plant (horsetails)from the Indian Cenozoic

- Climate change impacts the distribution of Quercus section Cyclobalanopsis(Fagaceae),a keystone lineage in East Asian evergreen broadleaved forests

- Resolving a nearly 90-year-old enigma: The rare Fagus chienii is conspecific with F.hayatae based on molecular and morphological evidence