Number and distribution of eosinophils and lymphocytes in the Japanese pediatric gastrointestinal tract: in search of a def inition for “abnormally increased eosinophils”

Mai Iwaya ·Shota Kobayashi·Yoshiko Nakayama·Sawako Kato·Shingo Kurasawa·Tomomitsu Sado·Yugo Iwaya·Takeshi Uehara·Hiroyoshi Ota

Abstract Background Primary eosinophilic gastrointestinal disorders (EGIDs) constitute chronic allergic inflammation.The number of eosinophils is one of the diagnostic criteria;more than 20 eosinophils per high-power field (HPF) in the gastrointestinal(GI) tract are considered abnormal in Japan.However,the quantity of eosinophils considered normal varies according to anatomical location and geographical region;such values have not been reported in Japanese pediatric patients,nor have the numbers of lymphocytes in the normal pediatric stomach.To establish a reference for defining diagnostic criteria for EGIDs,we evaluated the number of eosinophils in the normal Japanese pediatric GI tract.Methods We examined 131 biopsy cases without significant clinical history,endoscopic abnormality,or histological abnormality.Immunohistochemical analysis of CD3 and CD20 was performed.Results The mean eosinophil density was highest in the cecum (49.5 ± 22.4 per HPF).Counts of more than 20 eosinophils per HPF were observed in the duodenum [bulb (20.0 ± 9.6) and second portion (30.0 ± 15.8)],terminal ileum (38.3 ± 22.7),cecum (49.5 ± 22.4),ascending colon (42.3 ± 25.3),transverse colon (29.4 ± 17.0),and descending colon (32.2 ± 17.9).Counts of fewer than 10 eosinophils per HPF were observed in the stomach and rectum;a count of fewer than one eosinophil per HPF was observed in the esophagus.More than 100 CD3-positive T cells per HPF were observed in the stomach.Conclusions The mean numbers of eosinophils in the bowel were greater than 20 per HPF.For Japanese pediatrics,the current threshold eosinophil count should be revised.

Keywords Eosinophil·Gastrointestinal tract·Japanese·Lymphocyte·Normal·Pediatrics

Introduction

With improvements in environmental hygiene and sanitation,the prevalences of food allergies and other allergic diseases are increasing in the Japanese pediatric population.Primary eosinophilic gastrointestinal disorders (EGIDs)are Th2-mediated diseases that constitute chronic allergic inflammation in the gastrointestinal (GI) tract.EGIDs are subdivided into eosinophilic esophagitis (EoE) and eosinophilic gastroenteritis (EGE).EoE is limited to the esophagus;EGE involves the stomach,small bowel,and/or large bowel,regardless of esophageal involvement.Although histological evaluation of eosinophilic infiltration is necessary for diagnoses of EoE and EGE,it is challenging to define an “abnormally increased eosinophils” because the number of eosinophils considered normal in the GI tract varies according to anatomical location and geographical region[1,2].Several studies have reported a “normal number of eosinophils” in the GI tract in pediatric populations [2—5];to our knowledge,a cohort of Japanese pediatric patients has not been described.

In Japan,EGIDs are classified as designated intractable diseases by the Ministry of Health,Labor and Welfare;a Ministry-supported research group has provided recommendations for the diagnosis and management of EGIDs.These recommendations indicate that a count of more than 20 eosinophils per high-power field (HPF) in the lamina propria constitutes “abnormally increased eosinophils” in the stomach,small bowel,and large bowel;this def inition is a diagnostic criterion for EGE.Additionally,a count of more than 15 eosinophils per HPF in the esophageal squamous epithelium is a diagnostic criterion for EoE after exclusion of diseases that cause secondary tissue eosinophilia in the GI tract [6].Matsushita et al.investigated the number of eosinophils in the GI tract in healthy Japanese adults;they noted that a count of more than 20 eosinophils per HPF was frequently observed in the terminal ileum and right side colon,suggesting the need for distinct cut-off values among anatomical sites [7].Of course,the diagnosis of EGIDs should be made comprehensively,not only by the number of eosinophils but also by physical examination,laboratory tests and endoscopic findings,whereas there is a possibility that some patients might be misdiagnosed as EoE or EGE by the number of eosinophils in the GI tract due to insufficient or inadequate clinical examination.

Moreover,to our knowledge,the number of lymphocytes in the normal pediatric stomach has not been evaluated by immunohistochemistry.Here,we evaluated the numbers of eosinophils and lymphocytes in GI biopsy specimens without clinically and pathologically significant abnormalities in a cohort of Japanese pediatric patients.

Methods

Case selection

Study approval was obtained from the Research Ethics Board at Shinshu University (approval no.4810,July 29,2020).Totally 466 cases were retrieved involving children(< 16 years old) who underwent GI endoscopy and provided GI biopsies at Shinshu University Hospital between January 2017 and June 2019.Cases involving patients with a known medical history (e.g.,inflammatory bowel disease,Helicobacter pyloriinfection,hematopoietic disease,collagen disease,gastroesophageal reflux disease,and EGIDs)were excluded.EGID cases were defined as follows: patients undergoing treatment,who had a history of GI symptoms and exhibited more than 20 eosinophils per HPF in the stomach,small bowel,and/or large bowel or more than 15 eosinophils per HPF in the esophagus;diseases that caused secondary tissue eosinophilia were ruled out;symptoms and clinicopathological findings were improved by anti-allergy medication or food elimination therapy.Furthermore,cases involving increased eosinophils in the peripheral blood or abnormal endoscopic findings were excluded.Biopsy specimens were routinely collected from each segment to exclude microscopic abnormalities,even in patients with normal endoscopic findings.Hematoxylin and eosin (H&E)sections were reviewed by two gastrointestinal pathologists(MI and SK);cases with histological abnormalities (e.g.,active inflammation,reactive epithelial changes,or surface erosion) were excluded.Finally,131 GI biopsy cases involving 98 children without significant clinical and histological abnormalities were examined.For comparison,GI biopsy specimens collected from four patients with a known history of EGIDs in the same period were retrieved from the archive.

To evaluate the distribution of lymphocytes in the stomach,34 cases of upper GI tract biopsies from the 98 children were selected for immunohistochemical analysis.If there were three or fewer children in a particular age group,all cases were selected for immunohistochemistry;if there were more than three children in a particular age group,three cases were randomly selected for immunohistochemistry.Immunohistochemical staining was conducted using an automated slide preparation system (BenchMark ULTRA automated slide stainer,Ventana Medical Systems,Tucson,AZ,USA).The following primary antibodies were used in accordance with the manufacturers’ instructions: CD20(clone: L26,Leica,Germany) and CD3 (clone: LN10,Leica).

The numbers of eosinophils,CD3-positive lymphocytes,and CD20-positive lymphocytes were manually counted by two authors (MI and SK).To determine the number of eosinophils,all biopsies were assessed to identify the area with the highest number of eosinophils in each GI segment.To determine the numbers of CD3-positive cells and CD20-positive cells,“hot spots” in the lamina propria and muscularis mucosae were selected after exclusion of lymphoid follicles.Peak eosinophilic or lymphocytic counts were expressed per HPF.Counting was performed using a single type of microscope (Olympus BX 53,eyepiece: SWH10XH/26.5),focusing on an area of 0.345 mm2.

Statistical analysis

Normality was assessed using the Kolmogorov—Smirnov test.For nonparametric data,the Mann—WhitneyUtest was conducted,and for parametric data,Welch'sttest was conducted for statistical analysis.Differences were considered statistically significant whenP<0.05.Cohen’sdstatistic was calculated to determine the effect size.This parameter is calculated as the difference in the means of two groups divided by the weighted pooled standard deviations of these groups.A Cohen’sdvalue of 0.2 is considered a small effect,0.5 a medium effect,and 0.8 a large effect [8].All statistical analyses were performed using EZR (Saitama Medical Center,Jichi Medical University,Saitama,Japan),which is a graphical user interface forR(TheRFoundation for Statistical Computing,Vienna,Austria).

Results

Patient characteristics

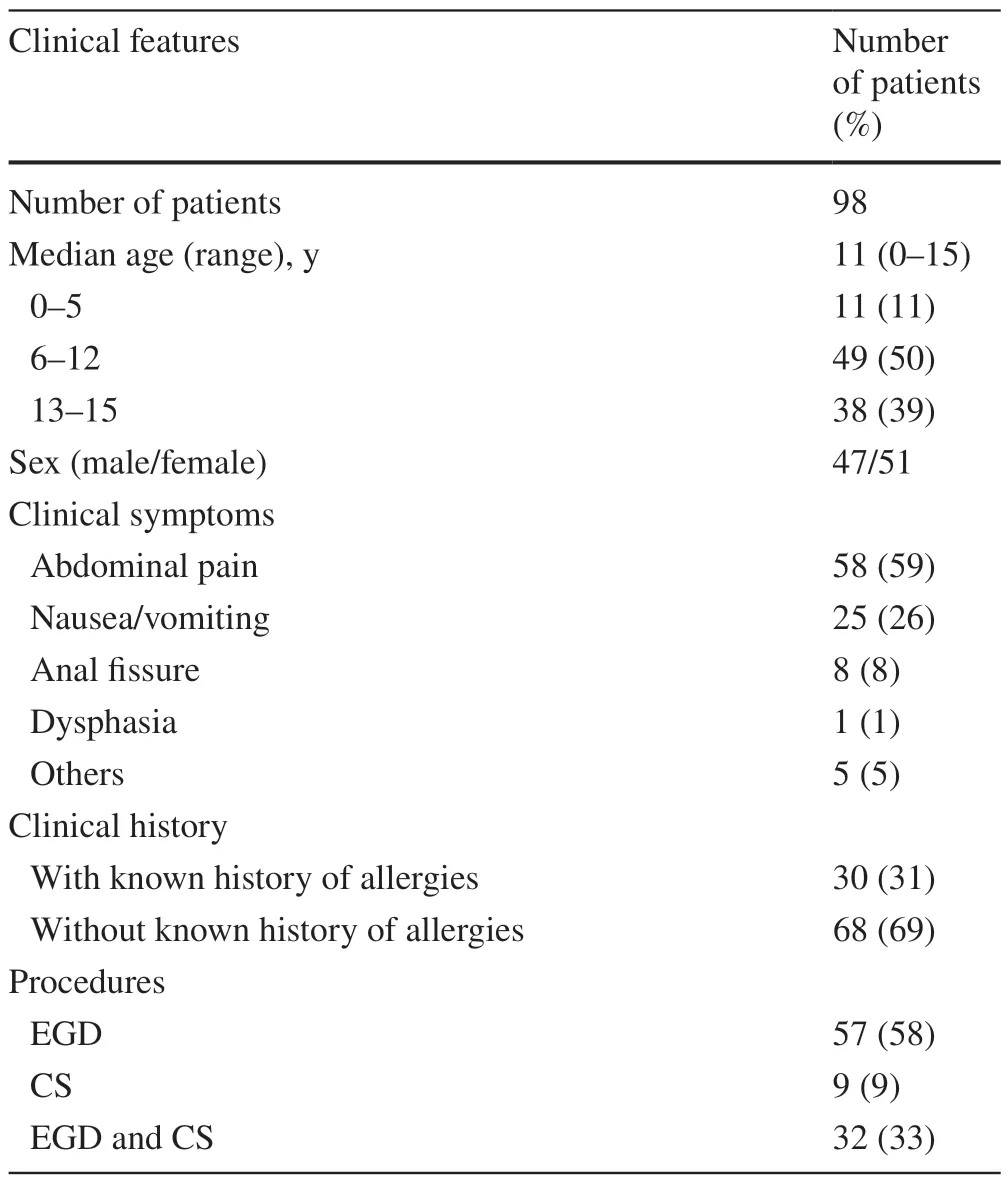

The 98 patients included 57 patients who underwent esophagogastroduodenoscopy (EGD),nine patients who underwent colonoscopy (CS),and 32 patients who underwent simultaneous EGD and CS.In total,753 biopsy specimens were evaluated.The median age of the included patients was 11 years (range 0—15 years);of the patients,47 were male,and 51 female.Frequent clinical symptoms were abdominal pain (59%) and nausea/vomiting (26%).Thirty of 98 patients(31%) had a known history of allergies,including food allergies (e.g.,egg,milk,and fruits),medication allergies,allergic rhinitis/conjunctivitis,asthma,and atopic dermatitis.A summary of patient characteristics is presented in Table 1.

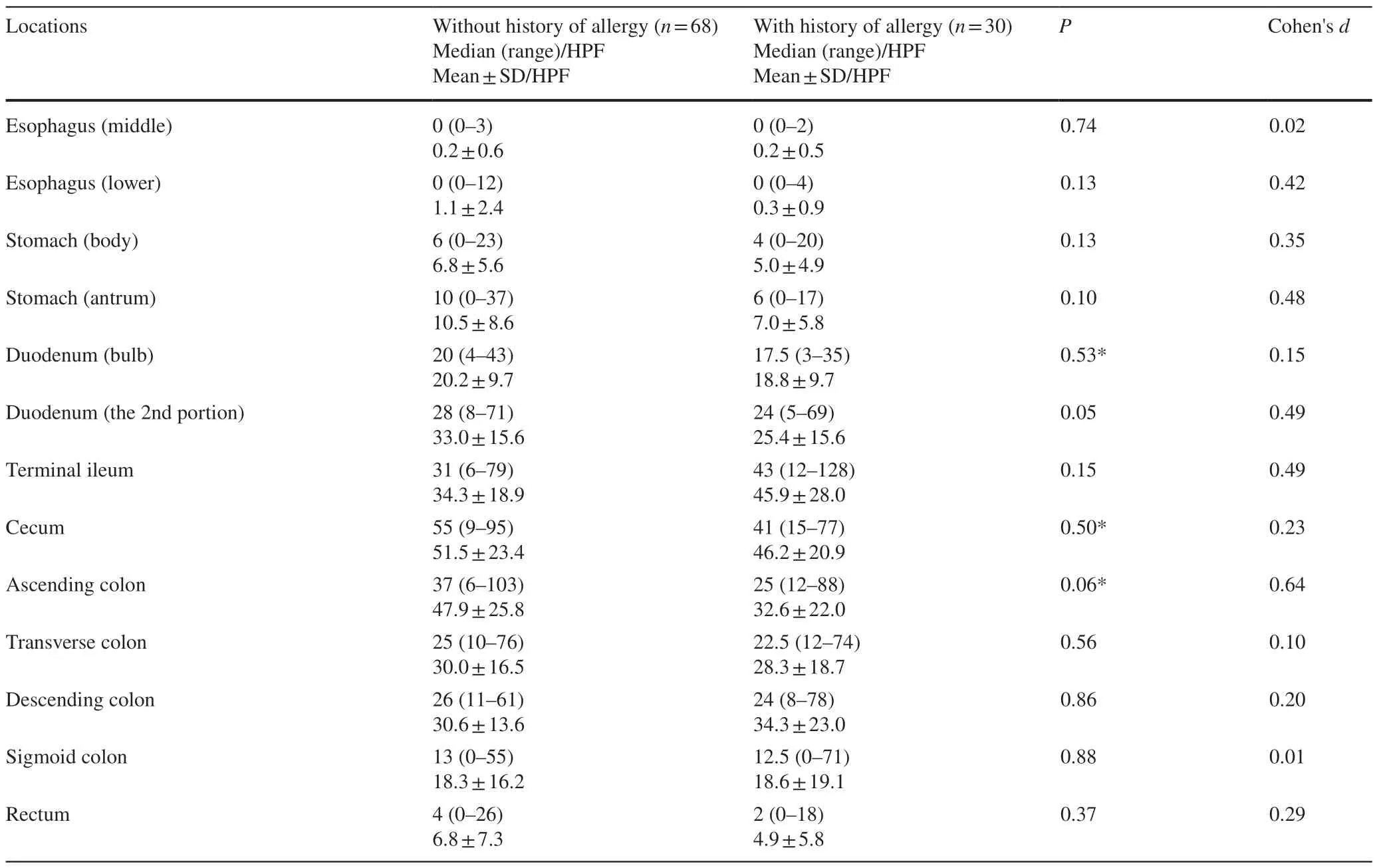

Table 1 Number of eosinophils in the GI tract

Numbers of eosinophils in each GI segment

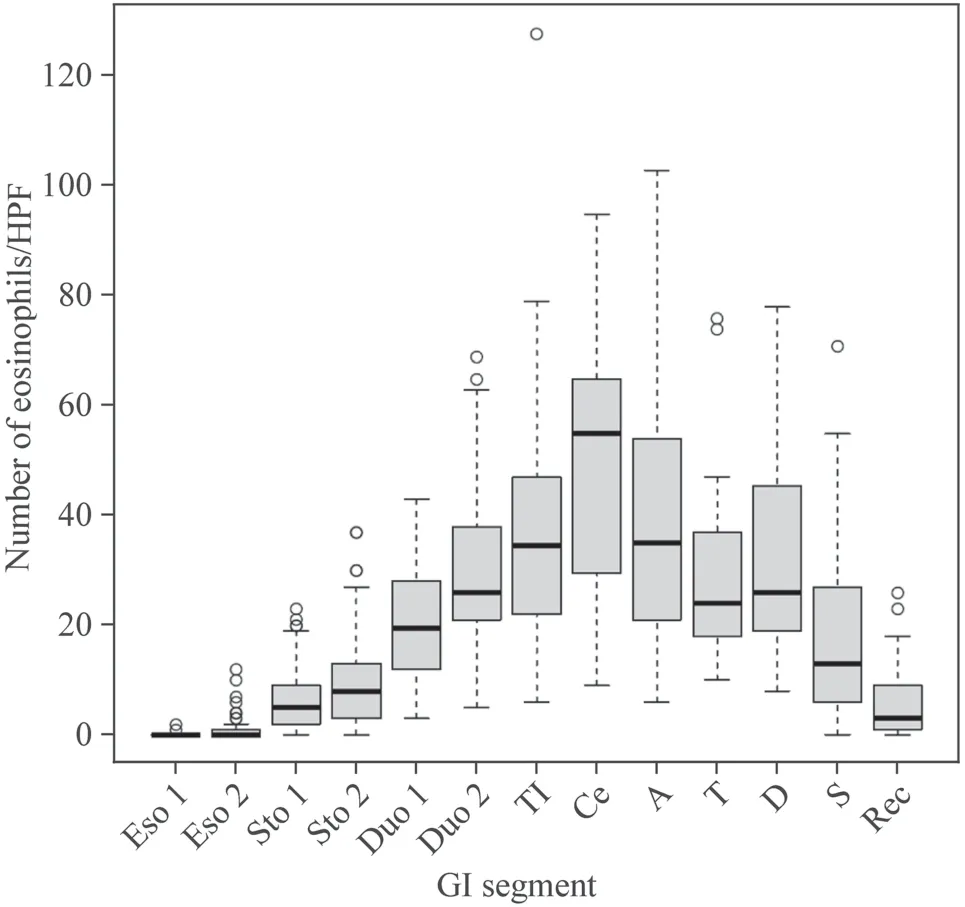

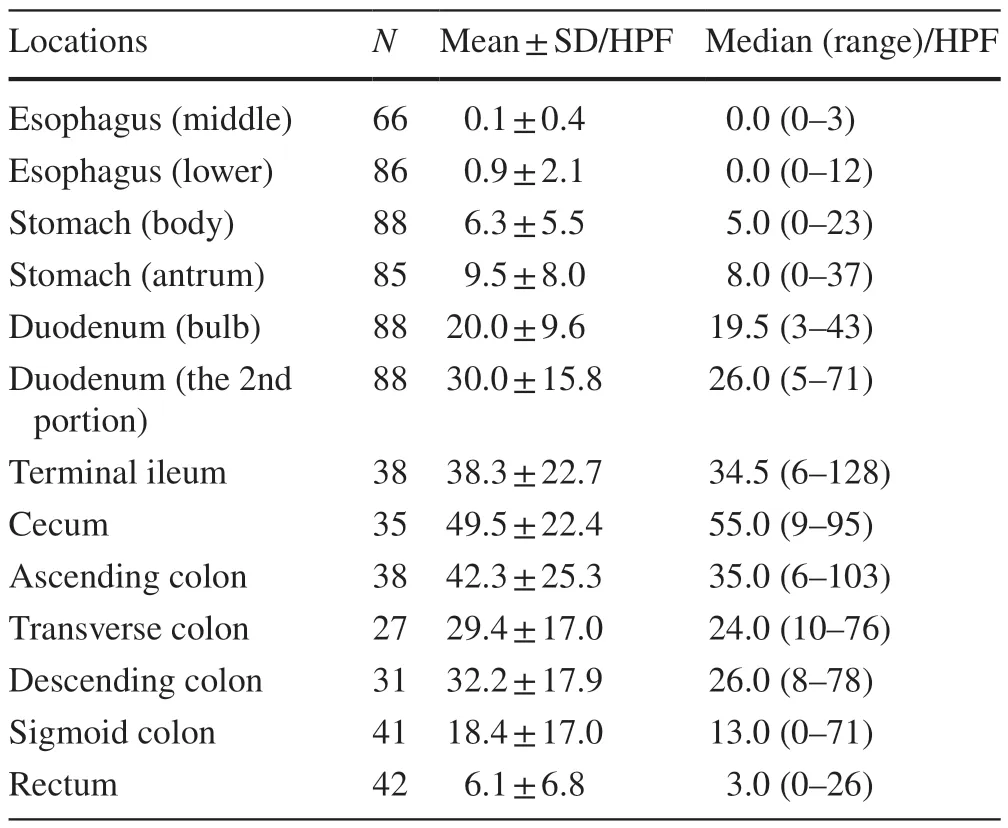

The numbers of eosinophils were significantly higher in the duodenum,terminal ileum,and right side of the large bowel(Figs.1,2).The mean eosinophil density was highest in the cecum (49.5 ± 22.4 per HPF).Eosinophils were more likely to be seen in the small bowel [terminal ileum (38.3 ± 22.7 per HPF)],duodenum [second portion (30.0 ± 15.8 per HPF)] and right side colon.In contrast,counts of fewer than 10 eosinophils per HPF were observed in the stomach(antrum and body) and rectum;a count of fewer than one eosinophil per HPF was observed in the esophagus (lower and middle) (Table 2).In patients without a known history of allergies,the eosinophil distribution was similar to that in the overall cohort.Additionally,no significant differences were identified in the number of eosinophils between the groups with and without a history of allergy,and Cohen’sdfor each location mostly demonstrated a small-sized effect(Table 3).

Fig.1 The mean number of eosinophils in each GI segment.In the esophagus,only a few eosinophils were observed;the number of eosinophils gradually increased through the stomach,duodenum,and terminal ileum;the highest number was observed in the cecum.The mean number of eosinophils decreased through the right-side colon,left-side colon,and rectum. Eso 1 middle esophagus,Eso 2 lower esophagus,Sto 1 gastric body,Sto 2 antrum,Duo 1 duodenal bulb,Duo 2 second portion of the duodenum,TI terminal ileum,Ce cecum,A ascending colon,T transverse colon,D descending colon,S sigmoid colon,Rec rectum

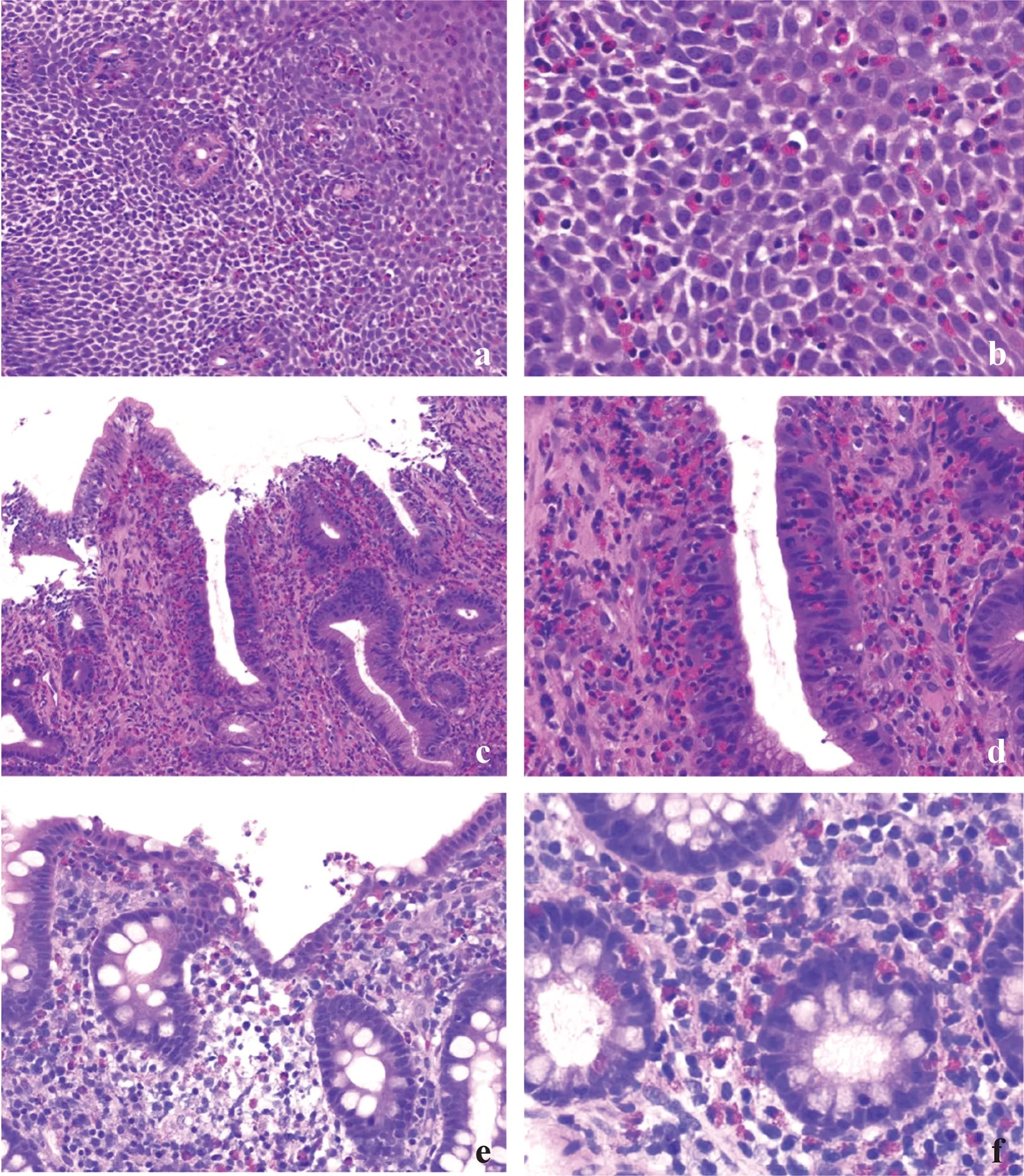

Fig.2 A biopsy from the gastric body,which initially exhibited few eosinophils (a);however,more than five eosinophils were evident throughout the image,using a higher-power view (arrow: eosinophil) (b).In the duodenum,eosinophils were clearly observed (c) [original magnification × 100 (d)];dense inflammatory infiltrate was observed with many eosinophils in the right colon (e).The number of eosinophils decreased in the left colon (f)

Table 2 Number of eosinophils in the GI tract

Table 3 Number of eosinophils in the GI tract;without and with known history of allergy

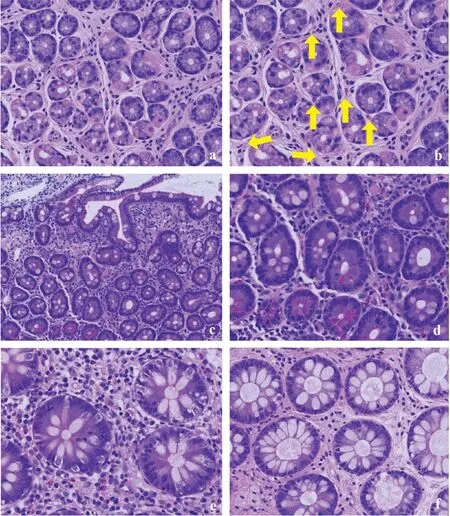

In contrast,the numbers of eosinophils in cases with a known history of EGIDs (one patient with EoE,three patients with EGE) were markedly higher than those in our cohort.Inf lamed areas showed counts of more than 70 eosinophils perHPF (Table 4) with eosinophilic abscess formation,epithelial reactive change,and/or erosion.Furthermore,dense eosinophilic infiltration prevented the quantification of eosinophils in some specimens (Fig. 3).

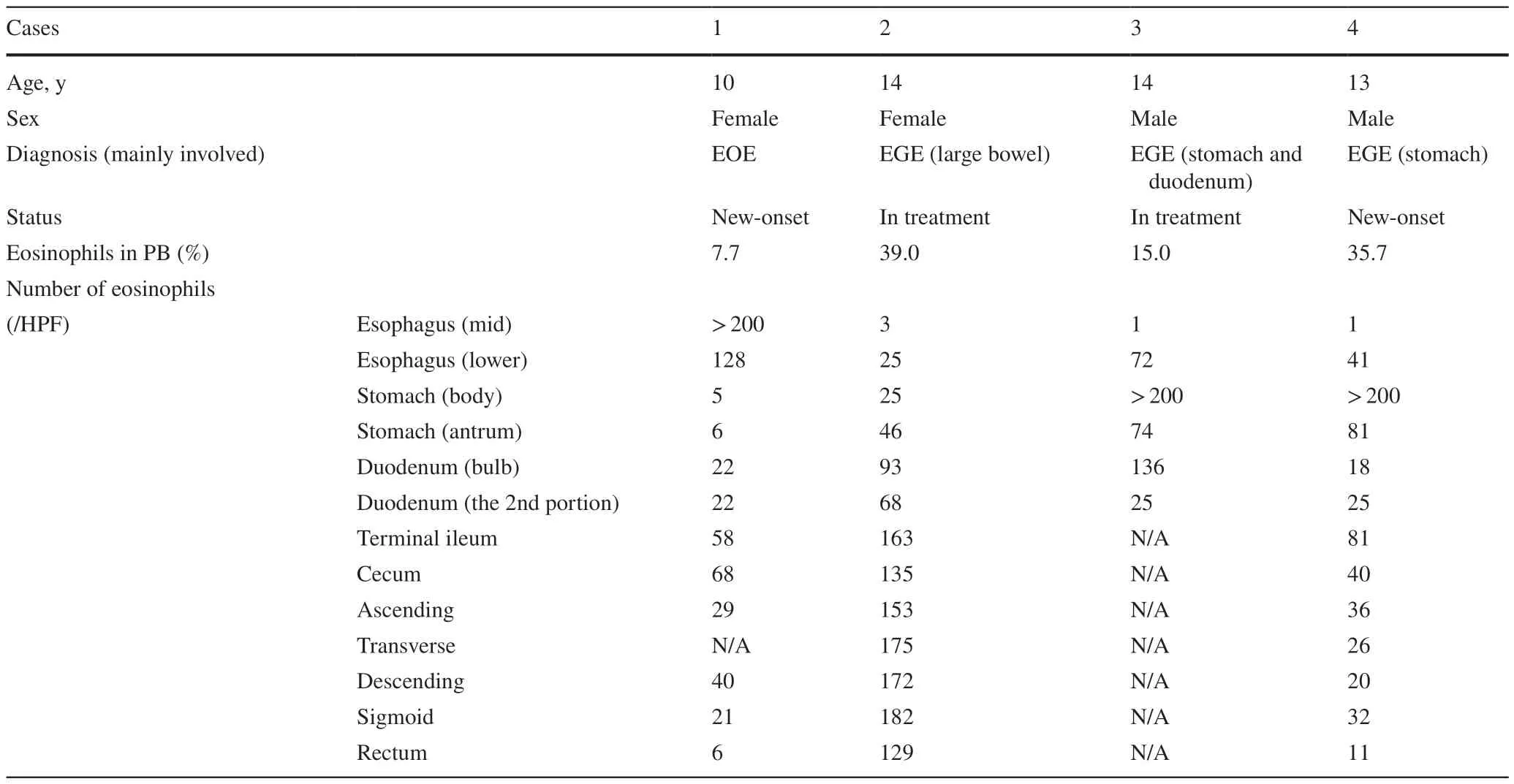

Table 4 The number of eosinophils in EGID pediatric patients

Numbers of lymphocytes in the stomach

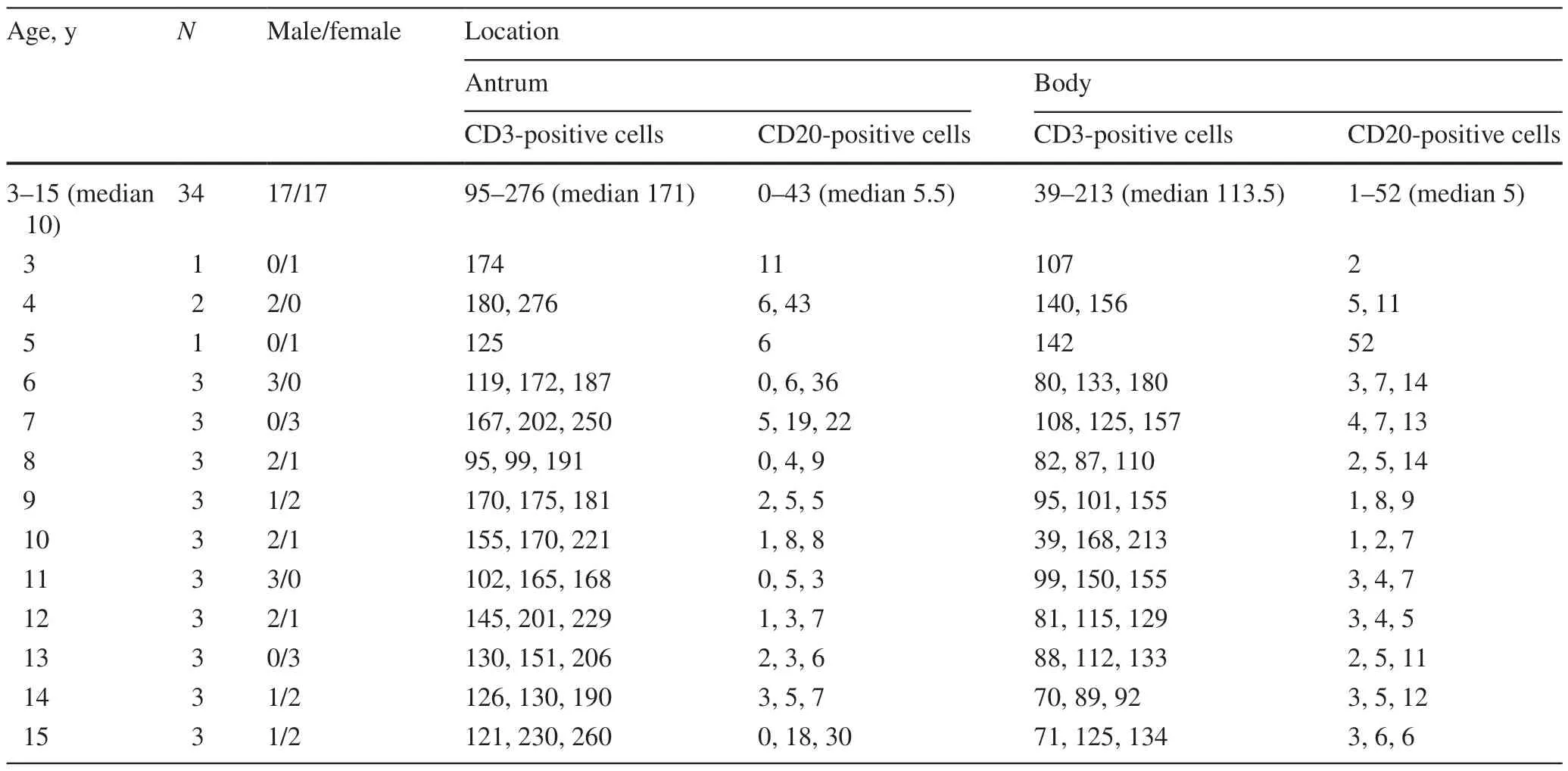

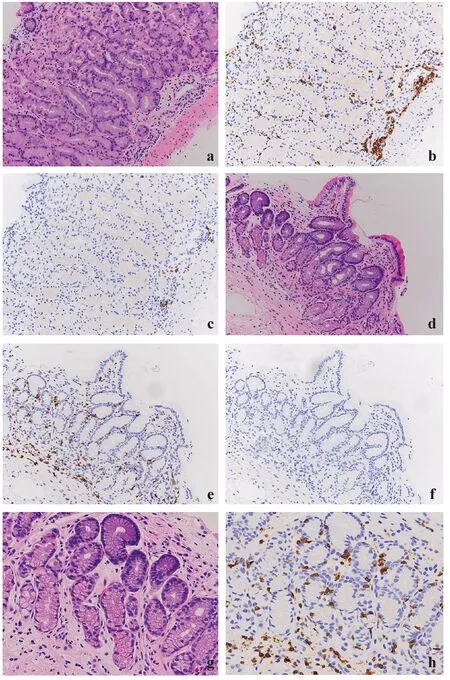

On H&E sections,some lymphocytes were indistinguishable from fibroblasts or other mononuclear cells in the lamina propria of the stomach;however,immunohistochemical staining revealed the distributions of CD3-positive T cells and CD20-positive B cells.CD3-positive T cells were prominent in both the antrum and body (respective ranges,95—276 and 39—213;respective medians,171 and 133.5),while CD20-positive B cells were less common in both areas (respective ranges,0—43 and 1—52;respective medians,5.5 and 5) (Fig. 4).The numbers of lymphocytes were not associated with age (Table 5).

Table 5 The number of lymphocytes in the stomach (per HPF)

CD3-positive T cells tended to surround foveolar pits,oxyntic glands,and pyloric glands;intraepithelial lymphocytes were occasionally observed.However,there were no instances of lymphoepithelial lesions present in MALT lymphoma (Fig. 4).

Discussion

We evaluated the number of eosinophils in the Japanese pediatric GI tract and found counts of more than 20 eosinophils per HPF in the duodenum,terminal ileum,cecum,and colon.Although counts of more than 20 eosinophils were occasionally observed in the stomach and rectum,no esophageal biopsy specimens showed more than 15 eosinophils per HPF.Furthermore,immunohistochemical evaluation of the numbers of lymphocytes in the stomach revealed more lymphocyte infiltration in the lamina propria than estimated by H&E staining;CD3-positive T cells were significantly more common in both the antrum and body than CD20-positive B cells.

Similar to the findings in prior studies,few or no eosinophils were identified in the esophagus in our cohort;this finding suggests that the current EoE diagnostic criteria in Japan and the criteria proposed by the American College of Gastroenterology are suitable for Japanese pediatric patients[9].However,compared with other pediatric cohorts in the United States and European countries [3—5],the numbers of eosinophils in the stomach,duodenum,terminal ileum,and large bowel were higher in our cohort.Our data were similar to the findings by Chernetsova et al.in Ontario,Canada;using a 0.55-mm2HPF area,they noted mean eosinophil counts of 50 per HPF in the cecum,20—35 per HPF in the distal colon,and 10 per HPF in the rectum [10].

The underlying reasons for the different numbers of eosinophils among studies are not fully understood;however,geographical factors may contribute to these differences.Pascal et al.reported that the number of eosinophils in the normal left colon was highest in the southern United States,and there was a 35-fold difference between New Orleans and Boston;they suggested that allergens in the environment or diet may influence the number of eosinophils in the colonic mucosa [1].This relationship may explain why our cohort of Japanese pediatric patients showed higher numbers of eosinophils in the GI tract (except esophagus) than prior studies performed in other countries;our findings imply potential hypersensitivity to aeroallergens.Tissue eosinophilia in some regions of the GI tract is affected by aeroallergens [11];Yamamoto et al.reported a high prevalence of allergic diseases among Japanese individuals compared with the populations of some European countries [12].Interestingly,even though cases involving individuals with a known history of allergies were excluded,counts of more than 20 eosinophils per HPF were clearly observed in the small bowel and the right side colon in our cohort.We evaluated the number of eosinophils throughout multiple seasons and multiple years;therefore,seasonal allergic rhinitis (mostly caused by Japanese cedar pollen [13]) and other unknown aeroallergens might have affected our data.

In Japan,the Ministry of Health,Labor and Welfare,as well as its research group,announced recommendations for the diagnosis and management of EGIDs.They defined a count of more than 20 eosinophils per HPF in the lamina propria as a diagnostic criterion for EGE;however,the threshold is lower than in prior studies [14—17].Ko et al.described pediatric cases with typical clinical and endoscopic features of eosinophilic gastritis;they used a strict threshold (70 eosinophils per HPF) to define the disease.No cases in our cohort met this criterion of 70 eosinophils per HPF.We also evaluated the number of eosinophils in EGID cases for comparison;we found extensive eosinophil infiltration with epithelial reactive changes,abscess formation,and/or erosion—these features were sufficient for the diagnosis of “gastroenteritis” or “esophagitis” in the involved GI segments.

Immunohistochemical analysis revealed that lymphocytic infiltration was underestimated by H&E staining.It has been described that small numbers of lymphocytes in the lamina propria and intraepithelial lymphocytes are T cells,while isolated lymphocytes in the lamina propria are B cells [18];however,the exact numbers of T cells and B cells in thestomach have not been reported.Although no cases exhibited histologically evident chronic inflammatory changes that were indicative of gastritis,a CD3-positive T-cell infiltrate of > 100/HPF was frequently observed;small numbers of CD20-positive B cells were also identified.CD3-positive T cells frequently surrounded foveolar pits,oxyntic glands,and/or pyloric glands;intraepithelial lymphocytes were occasionally observed.Although there were no features indicative of gastritis,the immunohistochemical findings in the epithelium were similar to the features of lymphocytic gastritis [19];therefore,we note that it is common to observe a large number of CD3-positive cells in the normal gastric mucosa during immunohistochemical analysis,and such a finding should be interpreted cautiously.

Fig.3 Eosinophilic infiltration of the GI tract in patients with known EGIDs.Esophageal biopsy from a patient with a known history of eosinophilic esophagitis (case a): extensive eosinophil infiltration was observed,along with epithelial spongiosis and basal hyperplasia (a,b).Extensive eosinophil infiltration in the gastric mucosa was observed in a patient with a known history of eosinophilic gastroenteritis (case c).Marked intraepithelial infiltration of eosinophils was observed,along with epithelial reactive change (c,d).Eosinophil infiltration with abscess formation was observed in the right side colon in a patient with a known history of eosinophilic gastroenteritis (case b) (e);dense eosinophil infiltration in the lamina propria and eosinophilic cryptitis were also observed (f). EGID eosinophilic gastrointestinal disorders,GI gastrointestinal

Fig.4 Gastric body biopsy (a) showing CD3-positive T cells infiltrating the deep lamina propria (b),while only a few CD20-positive B cells were identified (c).Gastric antral biopsy (d) showing diffuse infiltration of CD3-positive T cells (e) and a few CD20-positive B cells (f).Highpower view of the gastric antrum (g),with intraepithelial lymphocytes highlighted by CD3 immunohistochemistry (h)

Although most reports have described the number of eosinophils per HPF,the HPF size has not been specified.The field of view is calculated by the magnification of the objective lens and the diameter of the eyepiece;thus,the HPF size depends on the eyepiece field number.For universal standardization,eosinophil counting might be estimated using a field of 1 mm2;however,it would be a substantial practical burden for pathologists to count 3 or more areas of eosinophils per HPF for each biopsy specimen.The development of advanced techniques (e.g.,artificial intelligence)may solve this problem.

One limitation of our cohort was the use of a case selection approach because non-symptomatic pediatrics usually do not undergo endoscopy.Although we excluded cases with a known clinical history,abnormal endoscopic findings,or histological abnormalities,our cohort might be considered“relatively normal” in symptomatic Japanese pediatric populations.

In conclusion,we examined the number of eosinophils in the Japanese pediatric GI tract.We found that the numbers of eosinophils in the stomach,duodenum,terminal ileum,and large bowel were higher than those in previous studies performed in other countries;extensive differences were not found in the esophagus compared with previous studies.Compared with H&E staining,immunohistochemical analyses revealed significantly more lymphocytic infiltration in the gastric mucosa.Although the underlying pathological mechanisms are not fully understood,our findings of eosinophil infiltration imply hypersensitivity to aeroallergens in the Japanese pediatric population.Finally,using the current diagnostic criteria for EGE in Japan might cause some children to be misdiagnosed with EGE as a result of insufficient or inadequate clinical examination.

AcknowledgementsWe thank Ryan Chastain-Gross,Ph.D.,from Edanz (https://jp.edanz.com/ac) for editing a draft of this manuscript.Also cordially thank Masayoshi Koinuma,PhD,and the members of Center for Clinical Research,Shinshu University Hospital,for their insightful discussions in this work.

Author contributionsIM: conceptualization,methodology,investigation,data curation and writing of the original draft.NY: conceptualization,methodology,investigation,data curation,review and editing of the original draft.KSHO,KSA,KSHI and ST: investigation and data curation.IY: data curation and formal analysis.UT: conceptualization,methodology and supervision.OH: conceptualization,methodology,review and editing of the original draft,and supervision.All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

FundingThe authors did not receive any funding.

Data availabilityThe datasets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Compliance with Ethical Standards

Conflict of interestNo financial benefits have been received from any party related directly or indirectly to the subject of this article.

Ethics approvalThe study was carried out in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and was approved by the Shinshu University Research Ethics Committee (approval no.4810,July 29,2020).Our institutional review board waived the requirement for informed consent,and patients were provided with the opportunity to opt-out of the study.

World Journal of Pediatrics2023年3期

World Journal of Pediatrics2023年3期

- World Journal of Pediatrics的其它文章

- Monkeypox and the perinatal period: what does maternal–fetal medicine need to know?

- Monkeypox virus: past and present

- Stressful life events,psychosocial health and general health in preschool children before age 4

- Associations of preterm and early-term birth with suspected developmental coordination disorder: a national retrospective cohort study in children aged 3–10 years

- T-cell and B-cell repertoire diversity are selectively skewed in children with idiopathic nephrotic syndrome revealed by high-throughput sequencing

- Pathologic etiology and predictors of malignancy in children with cervical lymphadenopathy