营造健康:自然和设计的作用

著:(美)戴维·坎普 译:刘睿 校:陈崇贤

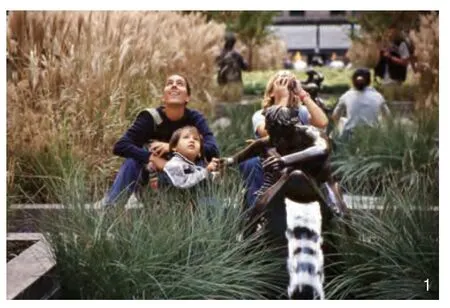

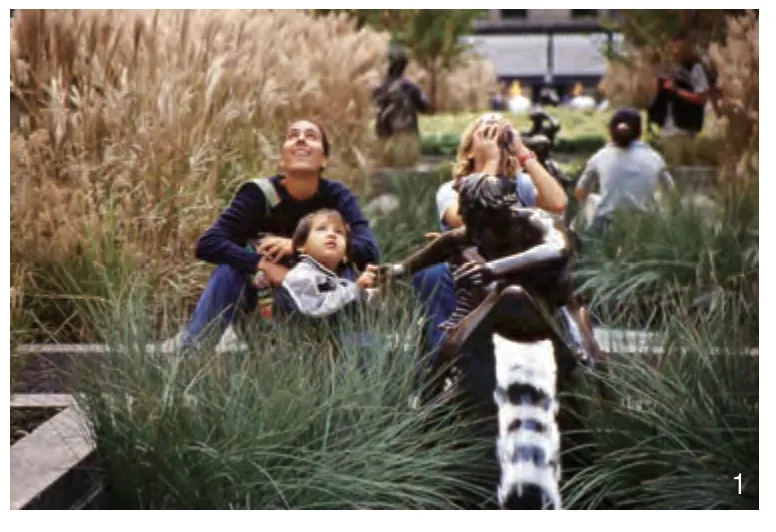

现在似乎是最好的时代,也是最坏的时代。我们的科技水平和应对能力达到前所未有的高度,但是我们给地球环境和居民基本健康所带来的威胁也是前所未有的。地球气候环境变得愈加不稳定,温室气体排放不断增加,生物多样性也在不断降低。当前,全球大部分发展最快的城市都处于生态敏感和不稳定的景观环境之中,缺乏能够支持居民基本生存质量的自然系统,现在是时候重视共同协作和创造性的思维了(图1)。

图1 纽约洛克菲勒中心海峡花园Rockefeller Center Channel Gardens, New York, NY

1 恢复平衡

几个世纪以来,科学技术改变了我们与自然的关系,人们一直渴望最大限度地减小自然对我们生活的影响。而今,风景园林师、建筑师和规划师,在强大的研究团队和拥护者的支持下,正引领着人们与自然界建立更紧密的联系[1]。城市历史学家Sam Bass Warner称之为:“恢复人类智慧。”①而社会生态学家Stephen Kellert称其为我们与生俱来的权利[2-3]②。E.O.Wilson将其描述为生物本能,一种与其他生命形式相联系的渴望[4]。这些观点的核心是自然、人类、基本福祉之间的根本联系。

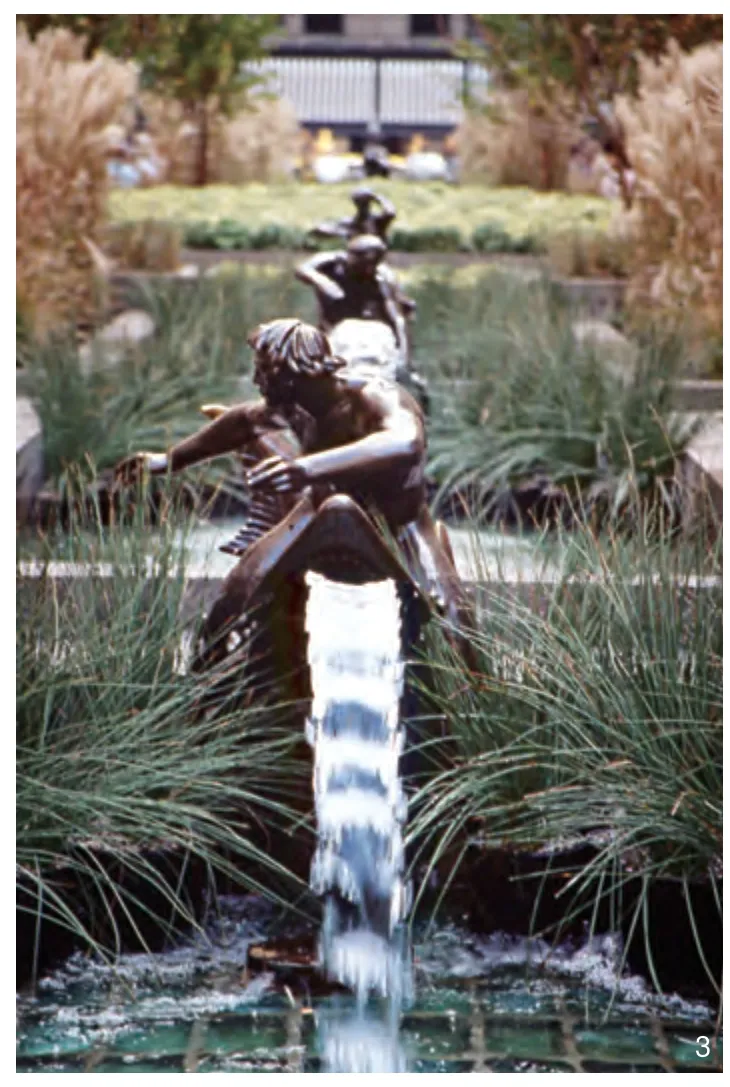

在稳定性和持续性受到威胁、脆弱性增加的危机时期,人类对亲近自然的需求从未像现在这样强烈。面对充满戏剧性和变数的未来,我们必须真诚无间、时刻保持一致,努力去平衡科技进步和我们对自然的内在需求。这要求我们审视疗愈科学与疗愈艺术的历史文化基础,制定具有敏锐性、适应性、整体性的设计响应措施,将设计实践作为一种带有协作和对话精神的社会艺术。将人类健康与环境健康作为一个共同体的设计理念,有助于将个体决策整合为集体决策,从而创建一个更具活力与公平的世界(图2)。

图2 创建改善健康和福祉的环境Creating settings that improve health and well-being

2 扩展健康和设计的概念

设计从业人员一直在倡导可持续和可再生的设计实践。多年来,其背后关于平衡资源利用和环境保护的理念,已经扩展到了更大的责任范围:不仅仅要给后代保留生存空间,还要通过恢复和修复自然系统并防止生态系统的破坏,以改善后代的生活。健康本源学则补充了这些理念:激励个体做出促进健康的决策。

健康本源学[5]是由社会学家Aaron Antonovsky提出的关于个人健康的理念。他的研究关注于压力、健康和福祉之间的关系。他提议的健康本源模型,是一种能够指导健康水平提升的理论。这个理论着眼于能够促进健康的因素而不是导致疾病的因素[6],其核心是心理一致感(sense of coherence)概念,这一概念阐述了压力对人体机能的影响,以及坚持将心理一致感(即可理解、可管理和有意义)作为目标的必要性。事实上,增强心理一致感——理解境遇、管理有效行动、找到意义,使我们能更好地应对生活的挑战。Antonovsky的假说强调了帮助个体认知生活品质,帮助他们理解品质如何影响个体行为和决策,都是十分重要的(图3)。

图3 利用设计和自然定义生活品质Using design and nature to help define a quality of life

正如我在其他地方提到过的,人们可能认为所有的设计都是为了健康本源的[7]。即使没有明确提出,我们也能意识到设计就是使环境变得可理解、可管理和有意义的艺术。设计是价值观的表达,我们选择建设的作品反映了我们的期望;我们的生活质量受已设计的、建成环境与自然环境之间关系的质量影响。然而要协调平衡无数的环境系统对设计师来说相当困难,这些环境系统会有力影响我们管理自然、技术、经济和人力资源系统的能力。个体健康的未来将在很大程度上依赖于设计的平衡:我们对生命意义的追寻绝不能被环境所阻碍,否则我们将失去坚持不懈的力量。相信Antonovsky的假说是有价值的,设计师在作品中有必要强调心理一致感,从而加强个体体验与社会环境需求之间的联系。

3 典型案例研究

以下案例研究是应用可持续、可再生和健康本源理论来解决复杂问题的代表项目,强调建成环境和自然界的关联性。这些案例同时也强调了设计作为提供给有识之士、社区参与乃至全球性倡议活动的有效资源,其超越尺度的能力(图4)。

图4 蓝色气候行动:转型机遇The Blue Climate Initiative: Transformational Opportunities

3.1 蓝色气候行动

蓝色气候行动(The Blue Climate Initiative)是一个为期多年的国际项目,旨在加快应对气候变化的海洋战略。蓝色气候行动由特提亚罗岛社会组织(Tetiaroa Society)发起,汇集了先锋实践者、研究人员和领袖,利用海洋的力量来解决这个时代所面临的巨大挑战,包括提供可再生的能源、可持续的食物供给、清洁的饮用水,进一步改善人类健康,丰富生物多样性以及实现可持续的海洋经济③。

2021年初,作为联合国海洋科学促进可持续发展十年计划(United Nations Decade of Ocean Science for Sustainable Development)的一部分[8],蓝色气候行动向全球范围的很多组织和社会团体颁发了创新气候解决方案奖。该行动旨在创建一个全球资源网络,利用世界沿海社区与国际研究和教育机构、非营利组织和可持续商业的活力和领导力,来创造和分享知识,推进新技术应用,促进教育协作和互联工作。目标是建立一个平台,以拓展和加强各个社区的工作成果,将创新的地域性对策转化为可实现和可转化的全球性战略。

为筹备蓝色气候行动建立了很多工作组以探索变革的机遇。我应邀加入了一个关注人类健康和福祉的工作组。我的合作者们来自世界各地,从美国马萨诸塞州的法尔茅斯到英国康沃尔郡的法尔茅斯,从伍兹霍尔海洋研究所到世界银行的气候变化和健康行动计划(World Bank’s Climate Change and Health Program)。我受邀分享了关于建成环境以及它与海岸环境关系的观点,围绕适应性的海岸基础设施提出了应对框架(图5)④。

图5 适应性海岸基础设施:概念图Adaptive coastal infrastructure: Concept image

研发适应性的海岸基础设施目的是模糊建成环境和海洋环境在理论和实践意义上的边界。力求将实体环境(我们的社区及其支持网络,如交通和公用事业)和经济系统(如商业和食品生产)与更大的目标相结合:在复杂且危机四伏的情况下,进行环境修复,为个体生存构筑经济、社会以及自我的韧性。最终将多样但相互关联的领域联系在一起,例如工程、生物和经济投资。

数百年来的沿海聚居导致在低洼和暴露地区增加了大量关键基础设施。这些庞大而老化的基础设施网络支撑着世界各地的沿海社区;许多这样的基础设施系统都不是按照抵御当今(或者未来)的环境风险来设计的。气候危机时代,在海平面上升以及风暴强度和频率不断增加的双重威胁下,老旧基础设施的各种弱点就暴露出来。

建造韧性基础设施并不意味着要建造更大或者更强的基础设施。韧性意味着灵活、快速响应和适应不确定未来的能力。在有限的资源日益紧张之际,设计师应推动现有基础设施的创造性改造进程;也应整合其他基础设施网络、自然系统和栖息地、可持续商业以及各个社区的具体需求,努力去实现涌现(emergence)和协同。21世纪的海岸基础设施已经不能再为线性的或索取能量这样狭隘的目的服务——海岸基础设施必须拥抱复杂性,能够可持续地运行,并且海岸将被视为一个持续的不断迁移变化的区域,不再是一个固定的边界。响应性基础设施要求设计师考虑社区的复杂性,确保规划工作建立在接触这些系统和网络的个人态度基础之上——无论是在确定关键问题方面,还是在展望可能的未来和预期的结果方面。构筑健康和韧性始于授权(图6)。

图6 纽约牙买加湾野生动物保护区的西部湖区生命海岸线West Pond Living Shoreline, Jamaica Bay Wildlife Refuge,New York, NY

3.2 西部湖区生命海岸线

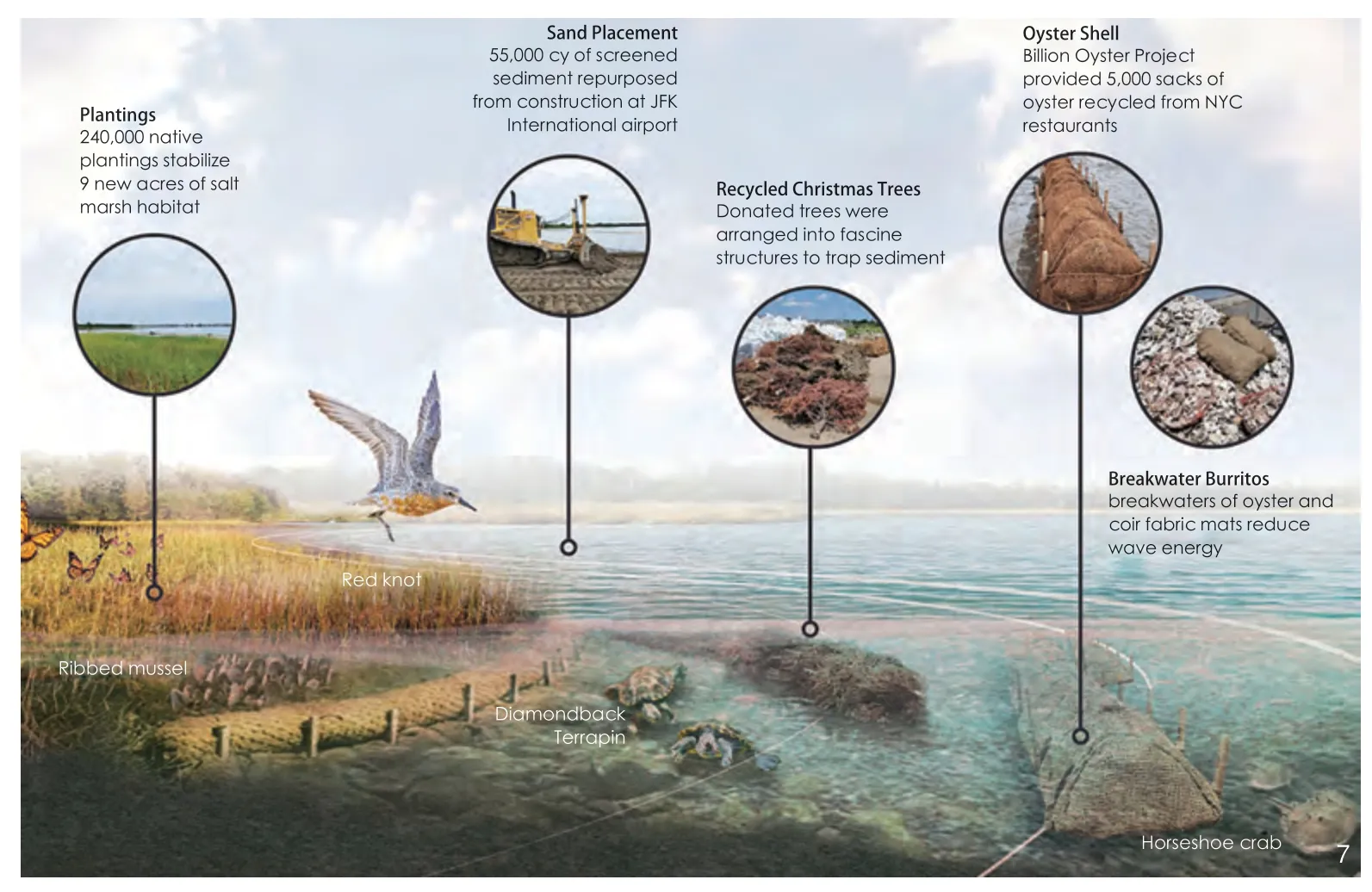

位于纽约皇后区牙买加湾野生动物保护区的西部湖区生命海岸线修复项目⑤,利用海湾的动力系统保护重要的栖息地和物种,同时让周围社区参与其修复。沿着脆弱的湖区边缘,综合了一系列设计策略以减弱波浪破坏影响、改善水质,并促进泥滩和盐沼的恢复。这种生命框架能够帮助湖区边缘修复,同时使这一脆弱的生态系统适应气候变化带来的诸多挑战。

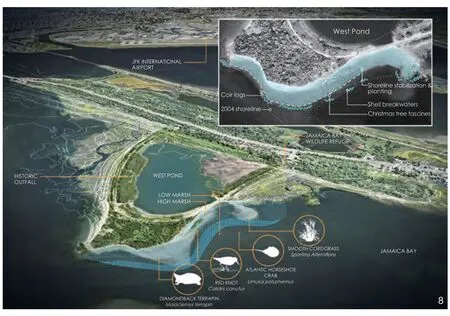

在过去的一个世纪里,纽约市失去了90%以上的淡水湿地。牙买加湾是现存最重要的湿地之一。西部湖区是牙买加湾生态系统中一个极其重要的淡水潟湖,具有非同寻常的文化和生态资源价值。世世代代以来,西部湖区一直是深受周边社区喜爱的自然资产,也是沿着大西洋迁徙候鸟的重要淡水资源。2012年,飓风“桑迪”使一道狭窄的堤坝决口,导致湖区的淡水与海湾的咸水混合。我们受邀来设计一个应对方案,该方案须兼顾多变的河口生态系统与国家公园管理局纲领性和可达性目标之间的复杂关联。我们的目标是利用牙买加湾的自然动力系统来重建、保护和维持西部湖区的关键沼泽栖息地(图7~9)。

图7 西部湖区生命海岸线:概念图West Pond Living Shoreline: Conceptual diagram

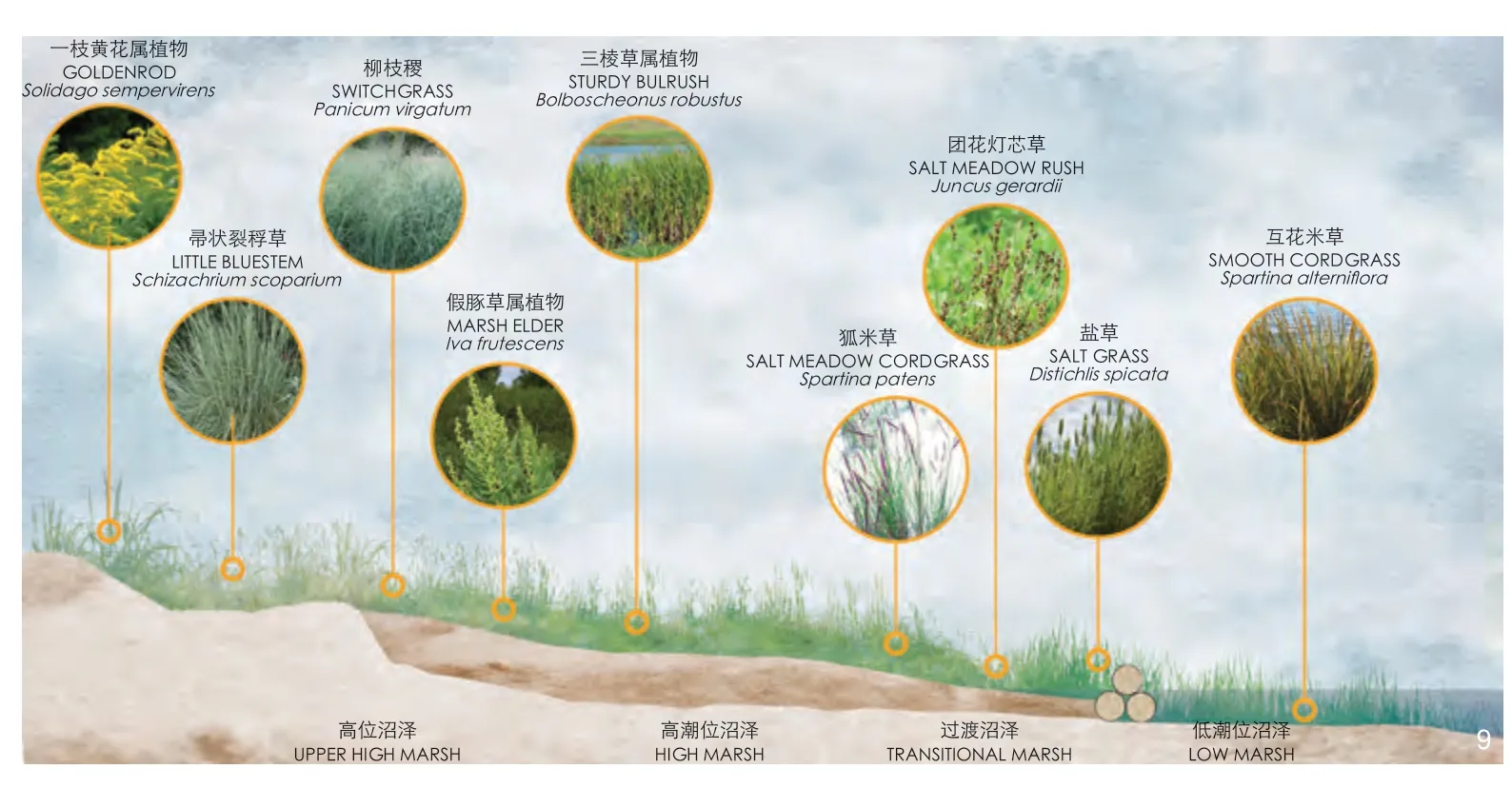

图8 概念剖面设计——设计将为这条脆弱的海岸线提供新的野生动物栖息地和保护带Conceptual section.The living design will provide new wildlife habitation and layers of protection along this vulnerable shoreline

图9 沼泽植物群落——海岸线种植了超过20万种本土的草本植物和灌木,减缓侵蚀的同时也为野生动物提供了栖息地Marsh planting communities.The shoreline was planted with over 200,000 native grasses and shrubs, limiting erosion, and providing wildlife habitat

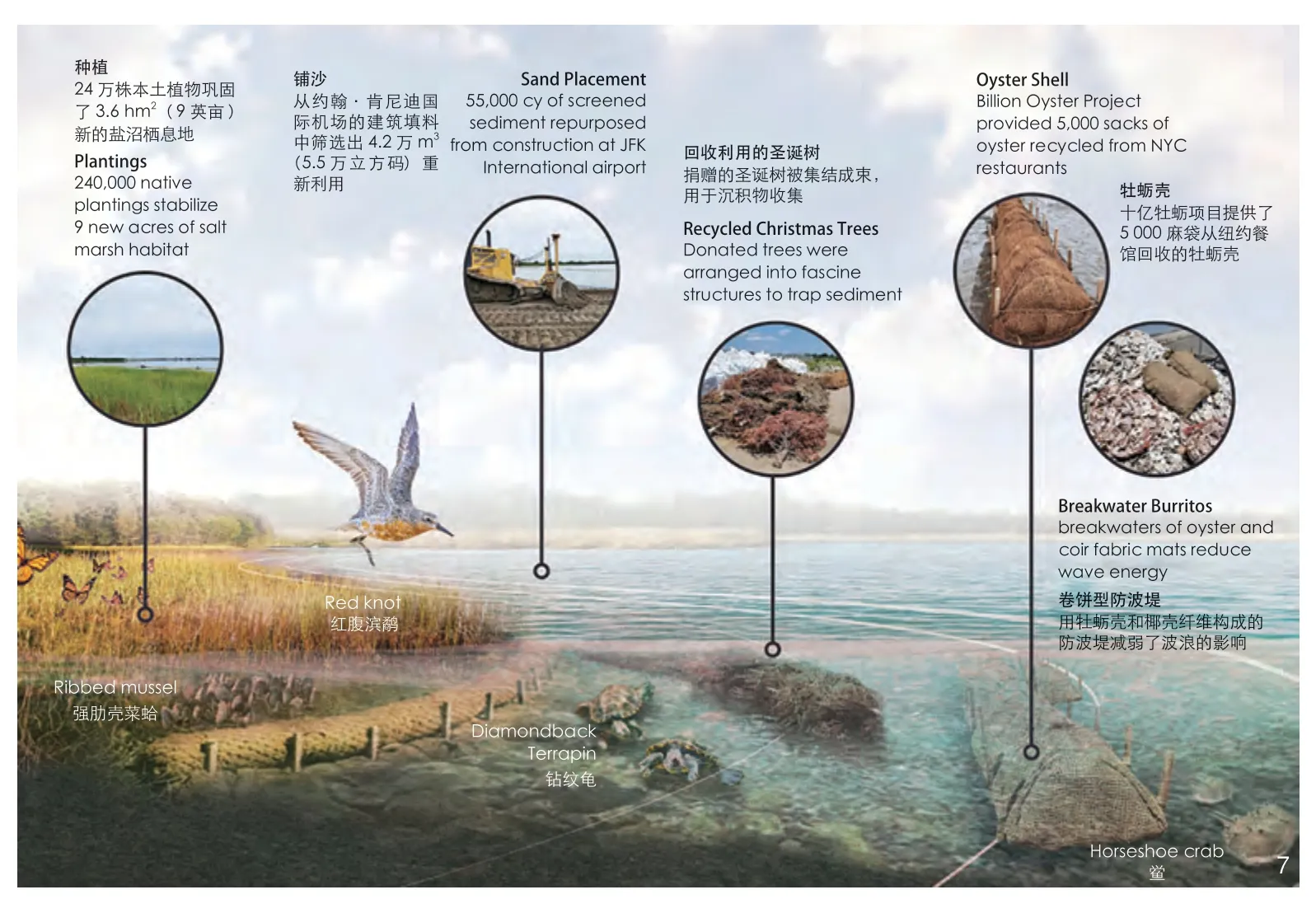

为了尽早减轻损害,时间至关重要。在18个月内,我们领导了一个由海洋工程师、生态学家、社区拥护者和志愿者组成的团队,设计并实施了一条732 m(2 400英尺)长的生命海岸线,创造了3.6 hm2(9英亩)左右的新栖息地,并恢复了5.7 hm2(14英亩)栖息地。我们沿着此前决口的位置,采取一系列的措施(包括增加防波堤结构、增加沉积物、种植湿地植物、控制侵蚀)以减弱波浪的影响、改善水质、促进泥滩和盐沼的恢复。这一生命框架满足了快速修复水域边缘的迫切需求,使脆弱的生态系统适应气候变化的挑战(图10)。

图10 为建造新的海岸线,从附近建筑工地引入清洁过的填料重新利用To create a new shoreline, repurposed cleaned fill was brought in from nearby construction sites

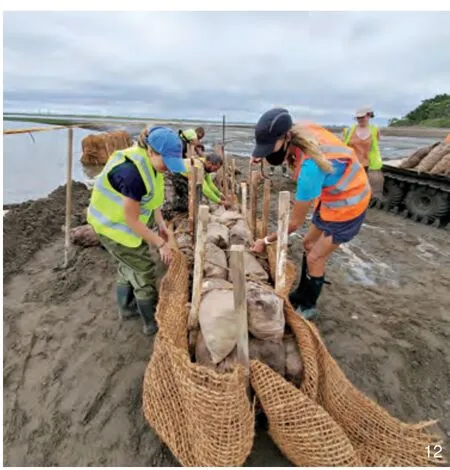

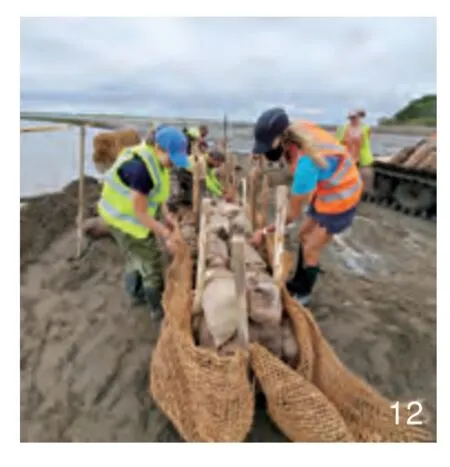

我们团队研究了各种可能的方法,包括天然存在的强肋壳菜蛤群落和人工构建的牡蛎礁结构,而由于国家公园管理局禁止水产养殖,我们认为牡蛎壳防波堤结构将会是这一区域最有效的解决方案。此外,还需要灵活应对疫情导致的供应链中断,紧密协作、灵活应对和具备创造力是必需的。这都是由于椰壳纤维主要来自斯里兰卡,而全球性的运输和生产迟滞迫使我们寻找替代材料。为此,我们与十亿牡蛎(Billion Oyster)项目⑥合作,从纽约市的餐馆获得了牡蛎壳。在阳光下暴晒了12个月后,牡蛎壳被打包放入由当地材料制作的粗麻布袋中。由于粗麻布在高盐条件下分解很快,我们提出了一种创新的“卷饼型防波堤”(breakwater burrito),将粗麻布袋堆叠成金字塔状,然后用椰壳纤维织物包裹住整个3.7 m(12英尺)长的结构。这种防波堤结构配合回收的圣诞树集束,减弱了波浪破坏,增加了沉积物,并保护新建的海岸线(图11、12)。

图11 起稳定作用的牡蛎壳通过十亿牡蛎项目的贝壳收集计划实现,并由志愿者将其放入可生物降解的袋子Oyster shells for our stabilization effort were collected through the Billion Oyster Project’s shell collation program and placed in biodegradable bags by volunteers

图12 创新的“卷饼型防波堤”用粗麻布袋装牡蛎,再堆叠成金字塔状结构,并用椰壳纤维织物包裹The innovative “breakwater burrito” was created by packing oysters in burlap, stacking them in a pyramidal structure, and wrapping the structure in coir fabric

基于健康本源的设计理念,社区参与对项目的成功至关重要。我们的任务包括协调当地环境保护组织和非营利机构的协同合作,并统筹数百名志愿者的工作。在施工期间要保护现有的栖息地和当地种群,包括对受保护的物种进行日常监测。例如,为680只繁殖期的雌性水龟构筑淤泥袋屏障,并培训施工人员检查施工设备下的阴凉处是否有午睡的水龟。

为了配合项目紧迫的时间节点,我们快速确定了关键性的策略,例如植物选择,因为本地的苗圃为我们准备24万株本土植物需要提前一年进行特定的扦插栽培。然后,将植物种植在盐沼和潮间带区域,以便在高潮位沼泽和淡水湖之间形成一个有韧性的交错带(图13、14)。

图13 在盐沼和潮间带种植植物,以支撑一个有韧性的海岸环境To support a resilient coastal condition, plantings were installed in salt marsh and intertidal zones

图14 基于健康本源的设计理念,社区参与对项目的成功至关重要Building upon the principles of salutogenic design,community engagement was essential for the project’s success

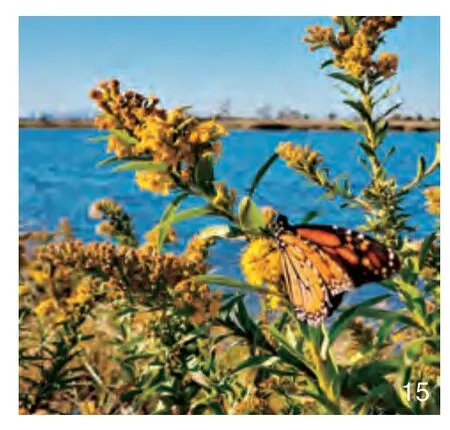

客户的目的是监测项目的长期健康状况,包括与牙买加湾科学与韧性研究所(Jamaica Bay Science and Resilience Institute)签订为期2年的合同。数据驱动的研究将支撑并启发生命海岸线设计,同时跟踪临近海域森林、灌丛、泥滩和湖泊淡水草本湿地的健康状况(图15)。

图15 数据驱动的研究将支撑并启发生命海岸线设计,同时跟踪临近区域生态系统的健康状况Data-driven research will sustain and inform this living shoreline design while tracking the health of the neighboring ecosystems

保护和维护西部湖区对于盖特威国家公园(Gateway National Park)生态系统的韧性至关重要,保护和维护社区管理的理念也同样重要。这一多学科、以社区为基础的行动为我们应对气候挑战提供了有效且重要的策略(图16)。

图16 该项目成功地营建了3.6 hm2(9英亩)新的滩涂湿地,并恢复了超过5.7 hm2(14英亩)的野生动物栖息地The project successfully created nine new acres of tidal wetland and restored over fourteen acres of wildlife habitat

4 优化策略

建设响应性的基础设施不仅仅是为了应对气候变化,也是为了完善公共卫生以应对未来不可预知的危机。新冠肺炎疫情也在提醒我们,改善每个人健康和福祉的工作还尚未完成。我们应如何在社区内建立有韧性和支撑性的健康结构体系?健康本源学设计让我们重新审视社区的规划,以便使人们更好地利用资源来适应变化,并做出明智的决策。设计师与经济、社会和环境科学等不同领域的专业人士协同合作,能更好地理解这些选择的决定因素,及其对我们的社区和公共环境的影响。综合了健康本源学、自然系统和技术的整体设计理念,与适应性的环境和社会基础设施相结合,有助于创造一个充满活力、有韧性和公平的未来。

注释:

① 引用了Warner未发表的论文《恢复性花园:为现代设计恢复一些人类智慧》。

② 耶鲁大学社会生态学教授Stephen R.Kellert出版了很多关于亲生物性概念的书,包括参考文献[2][3]。

③ 特提亚罗岛社会组织(Tetiaroa Society)是一个非营利组织,致力于保护法属波利尼西亚的环礁Tetiaro以及海洋的福祉。该组织由马龙·白兰度庄园(Marlon Brando Estate),该岛及岛上豪华度假酒店The Brando的所有者创立。详见https://www.tetiaroasociety.org/。

④ 这一概念来自David Kamp 2018年未发表的论文《适应性沿海基础设施》。

⑤ 牙买加湾野生动物保护区是1 093 hm2(27 000英亩)的盖特威国家休闲区(Gateway National Recreation Area)的一部分

⑥ 十亿牡蛎项目由一个总部位于纽约市的非营利组织发起。他们与当地社区合作,计划在2035年前为纽约港恢复十亿只活牡蛎。牡蛎礁为数百种物种提供栖息地,能够减弱巨浪的冲击、减少洪水并防止海岸线的侵蚀,进而保护城市地区免受风暴的破坏。

图片来源:

图1~3、16由Dirtworks景 观 事 务 所 拍 摄;图4由 特提亚罗岛社会组织蓝色气候行动提供;图5、7~9由Dirtworks景观事务所提供;图6、13、15由环保局Jean Schwarzwalder拍摄;图10由Dan Mundy二世拍摄;图11~12、14由Alex Zablocki拍摄。

(编辑/王一兰)

著者简介:

(美)戴维·坎普/男/ 美国风景园林师协会会员/Dirtworks景观事务所创始人/哈佛大学勒布学者/研究方向为健康环境设计

译者简介:

刘睿/女/硕士/绿化林业高级工程师/前上海植物园科研人员/低维护种植践行者/研究方向为华东区系适生植物应用与设计

校者简介:

陈崇贤/男/博士/华南农业大学林学与风景园林学院副教授/本刊特约编辑/研究方向为风景园林规划设计与理论

KAMP D.Building Health: The Role of Nature and Design[J].Landscape Architecture, 2023, 30(1): 20-29.DOI: 10.12409/ j.fjyl.202207260437.

Building Health: The Role of Nature and Design

Author:(USA) David Kamp Translator: LIU Rui Proofreader: CHEN Chongxian

Abstract:[Objective]This paper seeks to put individual health on a continuum with environmental health.It presents an approach to sustainable development that emphasizes the individual perspective in promoting health, a strategy that helps create conditions for individuals to better cope with life’s challenges,improve the quality of life and increase a sense of wellbeing and connectedness to nature.[Methods]Using case studies, the paper explores salutogenic design concepts that can help establish health-promoting resources for communities and address larger health inequalities.[Results]Salutogenic

concepts can be extrapolated to inform design choices, enhancing individual experiences and health-promoting outlooks within the framework of large-scale sustainable development initiatives.[Conclusion]A holistic design methodology incorporating salutogenesis, natural systems and technology with physical and social infrastructure can help create a healthy, vibrant, resilient, and equitable future.

Keywords: nature, design, and health; landscape design; salutogenic design;adaptive coastal infrastructure

It seems this is the best of times and the worst of times.Our capacity and potential and the technological and scientific resources we have at our disposal are unprecedented.Yet so are the threats to the basic health of the planet and its inhabitants.Biodiversity declines while greenhouse gas emissions increase as the Earth’s climate grows more erratic.Vast portions of the world’s fastest growing cities are built on ecologically sensitive,unstable landscapes that lack the natural support systems necessary to provide a basic quality of life for its inhabitants.It is time for collaborative and creative thinking (Fig.1).

1 Regaining Balance

For centuries technology and science transformed our relationship with nature, an aspiration reflecting an ever-increasing swing toward minimizing its influence in our lives.Now,landscape architects, architects, and planners,supported by a powerful group of researchers and advocates, are leading a shift back toward a more engaged relationship with the natural world[1].Urban historian Sam Bass Warner calls it “recovering some human wisdom”①while social ecologist Stephen Kellert says it is our birthright[2-3]②.E.O.Wilson described it as biophilia, the urge to affiliate with other forms of life[4].At its core is the fundamental link between nature, humans, and basic well-being.

The need for a connection to nature is never more poignant than in times of crisis, when stability and continuity are threatened, and our sense of vulnerability heightened.As we embrace a future of dramatic and complex change, we must maintain a concerted effort to balance our scientific and technological advancements with our intrinsic need for nature in a way that is genuine, intimate, and immediate.This effort demands we reflect on the historical and cultural underpinnings of the art and science of healing; crafting sensitive, adaptive, and holistic design responses; and practicing design as a social art, with dialog and collaboration.By putting human health on a continuum with environmental health, design can help individual choices coalesce into collective ones that lead to a more vibrant and equitable world (Fig.2).

2 Expanding Concepts of Health and Design

Design practitioners have long advocated for sustainable and regenerative design strategies.Over the years, the principles behind these methodologies, balancing resource use and environmental preservation, have expanded to encompass a larger responsibility: to not only accommodate but improve the life of future generations by restoring and repairing natural systems and preventing future ecosystem damage.Complementing these concepts is the idea of salutogenesis — motivating individuals to make choices that promote health.

Salutogenesis[5]is a perspective of personal health proposed by sociologist Aaron Antonovsky,whose research concerned the relationship between stress, health, and well-being.His proposal, the Salutogenic Model of Health, a theory to guide health promotion, looks at the factors that promote health rather than factors that cause disease[6].At its core is his “Sense of Coherence” construct, which describes the role of stress in human functioning and the need to maintain an orientation towards the world that is comprehensible, manageable,and meaningful.In essence, a fortified sense of coherence — comprehending a situation,managing effective actions, and finding meaning or purpose — better prepares us for life’s challenges.Antonovsky’s hypothesis emphasizes the importance of helping an individual determine a quality of life and understanding how that quality influences their behavior and choices (Fig.3).

图1 Rockefeller Center Channel Gardens, New York, NY

图2 Creating settings that improve health and well-being

图3 Using design and nature to help define a quality of life

图4 The Blue Climate Initiative: Transformational Opportunities

As I have written elsewhere, one can argue that all design aims to be salutogenic[7].If not explicit then by implication, design is the art of rendering the designed environment comprehensible, manageable,and meaningful.Design is an expression of values,reflecting our hopes and aspirations in what we choose to build; and our quality of life is influenced by the quality of the designed relationship between the built and natural environments.But it has become difficult for designers to balance the myriad physical systems that need to be accommodated with the forces that influence our ability to manage natural, technical, economic, and human resources.The future of personal health may well depend upon this balance: each of us must not be hampered by the environment in finding meaning in our lives or else we will not care enough to find the strength to persevere.Trusting that Antonovsky’s hypothesis has merit, it is essential for designers to emphasize a sense of coherence in the places we build, strengthening the threads that tie individual experiences to larger social and environmental needs.

3 Representative Case Studies

The following case studies represent projects that apply sustainable, regenerative, and salutogenic ideas to resolve complex problems, highlighting the interconnectedness of the built and natural worlds.They also emphasize design’s ability to transcend scale, serving as an effective resource for inspired individuals, engaged communities, and global initiatives (Fig.4).

3.1 The Blue Climate Initiative

The Blue Climate Initiative is a multiyear international program attempting to accelerate ocean-based strategies that combat climate change.Sponsored by the Tetiaroa Society, the initiative brings together pioneering practitioners,researchers, and leaders to leverage the power of our oceans to address some of the greatest challenges of our time: renewable energy,sustainable food supplies, clean drinking water,improved human health, flourishing biodiversity,and sustainable ocean economies③.

In early 2021, as part of an endorsed program of the United Nations Decade of Ocean Science for Sustainable Development[8], the Blue Climate Initiative granted awards for innovative climate solutions to a variety of communities and organizations around the world.The initiative seeks to create a global web of resources, leveraging the dynamism and leadership of the world’s coastal communities with international research and educational institutions, nonprofit organizations,and sustainable businesses to generate and share knowledge, advance new technologies and promote collaborative education and outreach efforts.The goal is to create a platform for extending and amplifying the work of individual communities,turning innovative local responses into realistic and transferable global solutions.

In preparation for this initiative, working groups were established to explore transformational opportunities.I was invited to join a group looking at human health and well-being.My collaborators came from across the globe — from Falmouth,Massachusetts, to Falmouth, Cornwall, from the Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution to the World Bank’s Climate Change and Health Program.Asked to contribute my perspective on the built environment and its relationship to coastal environments, I framed a response around the idea of adaptive coastal infrastructure (Fig.5)④.

图5 Adaptive coastal infrastructure: Concept image

图6 West Pond Living Shoreline, Jamaica Bay Wildlife Refuge,New York, NY

图7 West Pond Living Shoreline: Conceptual diagram

Developing an adaptive approach to coastal infrastructure intends to blur the boundaries of the built and marine environment practically and philosophically.It seeks to meld the physical environment (our communities and support networks such as transportation and utilities) and economic systems (such as commerce and food production) with larger goals: environmental remediation and building economic, societal, and personal resiliency for individuals living in complex and often daunting circumstances.It ties together diverse but interrelated perspectives, such as engineering, biology, and economic investment.

Centuries of coastal settlement have resulted in a vast accretion of critical infrastructure in low lying and exposed areas.These expansive, aging networks undergird coastal communities around the world;many of these systems were not designed to withstand today’s (or tomorrow’s) environmental stresses.The age of climate crisis exposed myriad vulnerabilities of these networks to the twin threats of sea level rise and increasing storm severity and frequency.

Building resilient infrastructure does not mean building bigger or stronger.Resilience implies a nimbleness, responsiveness, a capacity to adapt to uncertain futures.At a time of increasing strain on limited resources, designers should promote a process that includes the creative retrofitting of existing infrastructure; one that strives towards emergence and synergy — with other infrastructure networks, natural systems and habitats, sustainable commerce, and the unique needs of individual communities.Coastal infrastructure of the 21st century can no longer serve narrow purposes with linear, extractive flows of energy — they must embrace complexity, operate sustainably, and reflect a conception of the coast not as a fixed boundary but a continuous and migrating zone.Responsive infrastructure requires designers to embrace the complexity of communities, ensuring planning efforts are informed by the individuals these systems and networks touch — both in terms of identifying key issues but also in visioning possible futures and desired outcomes.Building health and resilience begins with empowerment (Fig.6).

3.2 West Pond Living Shoreline

The West Pond Living Shoreline Restoration Project, in the Jamaica Bay Wildlife Refuge in Queens, New York⑤, leverages the bay’s dynamic systems to protect critical habitat and species while engaging the surrounding community with its restoration.Along vulnerable pond edges,a constellation of design strategies coalesce to attenuate wave action, improve water quality, and support the reemergence of mudflats and saltmarsh.This living framework supports restoration of pond edges while adapting this vulnerable ecosystem to the many challenges presented by climate change.

Over the past century, New York City has lost over 90% of its freshwater wetlands.One of the most important remaining wetland areas is Jamaica Bay.West Pond, a critical freshwater lagoon within the larger Jamaica Bay ecosystem, is a resource of extraordinary cultural and ecological value.For generations, it has been a beloved community asset and vital freshwater source for migratory birds along the Atlantic Flyway.

In 2012, as the result of Hurricane Sandy, a narrow barrier was breached, mixing the pond’s fresh water with the bay’s saltwater.My firm, Dirtworks Landscape Architecture, PC was asked to develop a response, which considered the complex interplay of a shifting estuarine ecosystem alongside the National Park Service’s programmatic and accessibility goals.Our goal was to leverage Jamaica Bay’s dynamic natural systems to reestablish, protect and sustain West Pond’s critical marsh habitat (Fig.7-9).

图8 Conceptual section.The living design will provide new wildlife habitation and layers of protection along this vulnerable shoreline

图9 Marsh planting communities.The shoreline was planted with over 200,000 native grasses and shrubs, limiting erosion, and providing wildlife habitat

图10 To create a new shoreline, repurposed cleaned fill was brought in from nearby construction sites

图11 Oyster shells for our stabilization effort were collected through the Billion Oyster Project’s shell collation program and placed in biodegradable bags by volunteers

图12 The innovative “breakwater burrito” was created by packing oysters in burlap, stacking them in a pyramidal structure, and wrapping the structure in coir fabric

To ameliorate the damage as quickly as possible, time was of the essence.Leading a team of marine engineers, ecologists, community advocates and volunteers, within eighteen months we designed and implemented a 2,400-foot living shoreline, creating over nine acres of new habitat, and restoring fourteen acres.Along the formerly breached dam edge, a constellation of strategies — breakwater structures, additional sediment, marsh plantings and erosion control —coalesce to attenuate wave action, improve water quality, and support the reemergence of mudflats and saltmarsh.This living framework supports the immediate need to restore the pond edge while adapting this vulnerable ecosystem to the challenges of climate change (Fig.10).

Our team studied a variety of possible approaches, including naturally occurring rib mussel communities and spat-on-shell oyster reef construction.Due to the National Park Services’mandate against aquaculture, we determined that an oyster shell breakwater structure would be the most effective solution here.Nimble responses to supply chain and pandemic-related disruptions required close collaboration, flexibility, and creativity.It all came down to coconut fiber.With most coconut fiber coming from Sri Lanka, a global slowdown in shipping and production forced us to consider alternative materials.Partnering with the Billion Oyster Project⑥, we sourced recycled oyster shells from New York City restaurants, cured them in the sun for twelve months, and then packed them in locally sourced burlap bags.Because burlap breaks down faster in high salt conditions, we developed an innovative “breakwater burrito” by packing the burlap bags, stacking them in a pyramidal structure, and then wrapping the entire twelve-footlong assembly with coir fabric.These breakwater structures, together with recycled Christmas tree fascines, attenuate wave action, accrete sediment, and protect the newly constructed shoreline (Fig.11-12).

Building upon the principles of salutogenic design, community engagement was essential for the project’s success.Our work included coordinating the collaborative efforts of local environmental advocacy groups and nonprofits and overseeing the work of hundreds of volunteers.Existing habitat and native populations needed protection during construction, which included establishing a program of daily monitoring for protected species.Silt sock barriers were installed for six hundred eighty breeding terrapin females and construction crews were trained to check for terrapins who might take a midday nap in the shade under construction equipment.

图13 To support a resilient coastal condition, plantings were installed in salt marsh and intertidal zones

图14 Building upon the principles of salutogenic design,community engagement was essential for the project’s success

图15 Data-driven research will sustain and inform this living shoreline design while tracking the health of the neighboring ecosystems

图16 The project successfully created nine new acres of tidal wetland and restored over fourteen acres of wildlife habitat

To accommodate the project’s concentrated timeframe key design strategies, such as plant selections, were quickly determined because local nurseries needed to begin growing the specified plugs for our 240,000 native plantings a year in advance.Plantings were installed in salt marsh and intertidal zones, creating a resilient ecotone between the high marsh and freshwater pond (Fig.13-14).

Our client’s goal to monitor the longterm health of the project included a twoyear contract with the Jamaica Bay Science and Resilience Institute.Data-driven research will sustain and inform this living shoreline design while also tracking the health of the neighboring maritime forest, shrubland, mudflat, and lacustrine freshwater herbaceous wetlands (Fig.15).

Protecting and sustaining West Pond is critical to the resiliency of the larger Gateway National Park ecosystem.Equally critical is protecting and sustaining the idea of community stewardship.This multi-discipline, community-based initiative establishes an effective and vital response to our changing climate (Fig.16).

4 Optimizing Strategies

Building responsive infrastructure deals not only with climate change but also with optimizing public health for future crises.The COVID-19 pandemic is a humbling reminder of the work that is yet to be done to improve the health and wellbeing of everyone.How do we create resilient and supportive health structures within our communities? Salutogenetic design allows us to reconsider the planning of our communities to better equip people with the resources to adapt and make informed choices.Working collaboratively with professionals in diverse fields, such as economics,social and environmental science, designers can better understand the factors shaping these choices and their influence on our communities and the environment we share.A holistic design methodology incorporating salutogenesis, natural systems and technology, in combination with adaptive physical and social infrastructure, can help create a vibrant, resilient, and equitable future.

Notes:

① The Warner quote is from his unpublished paper“Restorative Gardens: Recovering Some Human Wisdom for Modern Design.”

② Stephen R.Kellert, a professor of social ecology at Yale, published many books incorporating the concept of biophilia, including reference [2][3].

③ The Tetiaroa Society is a nonprofit focused on the conservation of Tetiaroa, an atoll in French Polynesia,and the well-being of the oceans.The organization was founded by the Marlon Brando Estate, owners of the island and its luxury resort hotel, The Brando.See https://www.tetiaroasociety.org/.

④ The concept is from David Kamp’s 2018 unpublished paper “Adaptive Coastal Infrastructure.”

⑤ The Jamaica Bay Wildlife Refuge is part of the 27,000-acre Gateway National Recreation Area.

⑥ The Billion Oyster Project is a New York City-based nonprofit organization working in collaboration with local communities to restore one billion live oysters to New York Harbor by 2035.Oyster reefs provide habitat for hundreds of species and can protect urban areas from storm damage by softening the blow of large waves, reducing flooding,and preventing erosion along the shorelines.

Sources of Figures:

Fig.1-3, 16 photo by Dirtworks, PC; Fig.4: courtesy of Tetiaroa Society, Blue Climate Initiative; Fig.5, 7-9:courtesy of Dirtworks, PC; Fig.6, 13, 15 photo by Jean Schwarzwalder/DEP; Fig.10 photo by Dan Mundy, Jr.;Fig.11-12, 14 photo by Alex Zablocki.

(Editor / WANG Yilan)

Author:

(USA) David Kamp, FASLA, is the founding principal of Dirtworks Landscape Architecture, PC., and a Harvard Loeb Fellow.His research focuses on promoting health through design and nature.

Translator:

LIU Rui, Master, is a senior engineer of landscape architecture, former scientific researcher of Shanghai Botanical Garden, low maintenance planting practitioner.Her research focuses on plant design of East China.

Proofreader:

CHEN Chongxian, Ph.D., is an associate professor in the School of Forestry and Landscape Architecture, South China Agricultural University, and a contributing editor of this journal.His research focuses on landscape planning and design, and theory of landscape architecture.