Entire process of electrocardiogram recording of Wellens syndrome: A case report

Na Tang, Yi-Hua Li,Liang Kang,Rong Li, Qing-Min Chu

Abstract

Key Words: Wellens syndrome; Pseudo-normalized T-waves; Unstable angina pectoris; Myocardial ischemia; Electrocardiogram; Case report

lNTRODUCTlON

First described by de Zwaanet al[1] in 1982, Wellens syndrome is an important electrocardiogram (ECG) pattern, indicating severe stenosis in the left anterior descending (LAD) coronary artery. It is characterized by inverted or biphasic T-waves at precordial leads in angina-free periods, but shows positive or “normalized” T-waves during angina, which complicates the diagnosis. These positive or “normalized” T-waves are called pseudo-normalized T-waves[2] and might delay recognition of the emergency status of patients with chest pain. Here, we report a case of Wellens syndrome to deepen our understanding of these ECG signs.

CASE PRESENTATlON

Chief complaints

Chest pain, dyspnea.

History of present illness

A 47-year-old male patient was admitted with the chief complaint of repeated unprovoked chest pain for more than 20 da, which was aggravated for 1 d. After getting up early in the morning on the day of admission, he experienced paroxysmal chest pain again, which lasted for more than 30 min, in addition to radiating pain to the left arm and exertional dyspnea. At 18:30, the patient presented to the emergency department but had no chest pain or other discomfort at that time.

History of past illness

The patient had a history of smoking > 20 cigarettes per day for over 20 years, type 2 diabetes for 5 years, and gout for 2 years.

Personal and family history

No remarkable personal and familial medical history was identified.

Physical examination

At admission, the patient’s temperature was 37.0 °C, pulse was 99 bpm, and blood pressure was 13.9/9.6 kPa. Cardiopulmonary and abdominal physical examinations showed no obvious abnormalities.

在后来的日子里。敦礼只要是没有特别的事情,总是尽早结束上午的工作,准时赶到月半湾,他慢慢恋上了餐厅的宁静以及与那个女子背对背默然相守的温馨,他把自己深深地浸泡在这两种元素中。大多数时候,他都心甘情愿地把女子当作餐厅的一部分,就像餐桌上方那盏深色的吊灯,或者墙角摆放的绿萝,没有多大必要去打扰她或者认识她。并且认为也许正是因为这样的一种相守,才会使人流连,使人无法释怀,倘若真的相识,敦礼闭上眼沉思,倘若真的相识,那又会怎样呢?

Laboratory examinations

Upon admission, the patient’s serum high-sensitivity cardiac troponin I concentration was 0.317 ng/mL (normal range: 0-0.034 ng/mL). A serum lipid panel showed that the total cholesterol concentration was 5.44 mmol/L↑ (normal range: 2.6-5.2 mmol/L), low-density lipoprotein was 3.78 mmol/L↑ (normal range: ≤ 3.37 mmol/L), triglycerides were 1.65 mmol/L (normal range: 0.34-1.70 mmol/L), and highdensity lipoprotein was 1.10 mmol/L (normal range: > 1.04 mmol/L).

Imaging examinations

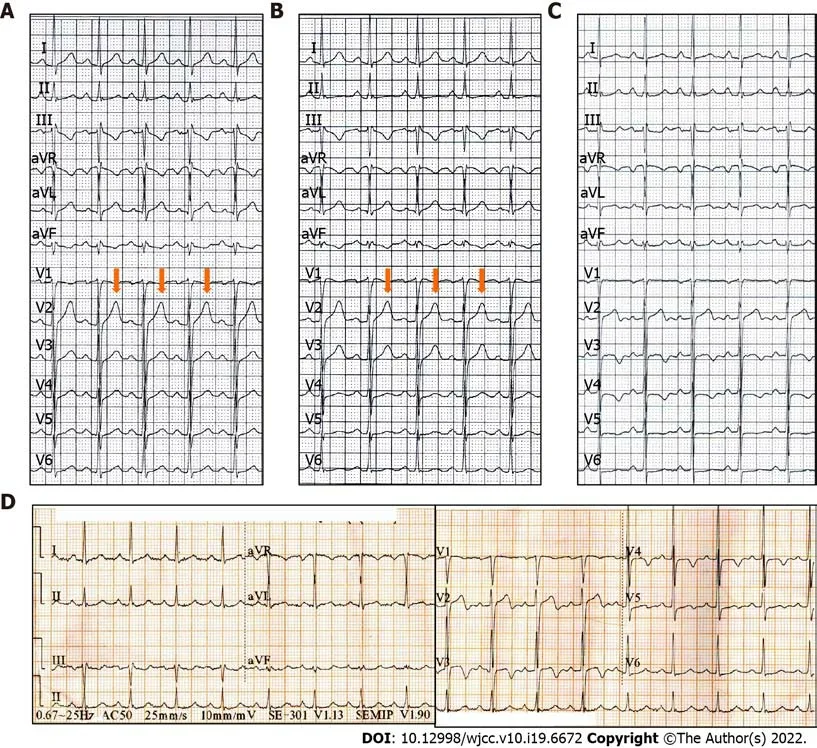

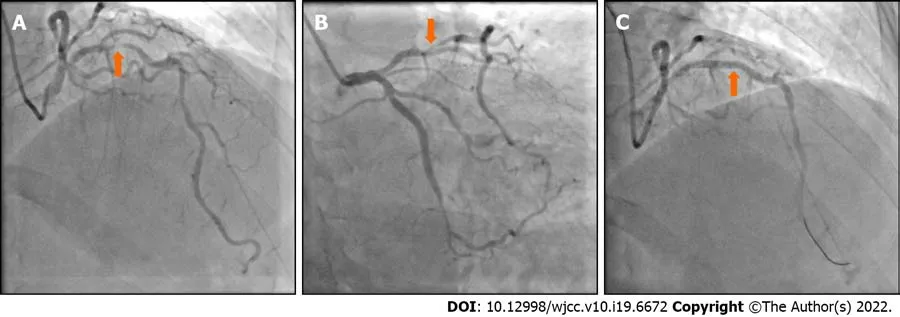

The ECG (Figure 1A and B) and myocardial enzymology examinations were normal when angina was present, while the ECG showed inverted or biphasic T-waves when angina was absent (Figure 1C). The ECG at presentation (Figure 1D) showed sinus tachycardia and T-wave changes, which were identified as Wellens syndrome when combined with previous ECG findings. Coronary angiography (CAG) showed localized stenosis of the proximal LAD (90%-95%; Figure 2), the D1 ostium (60%-70%), and the middle portion of the left circumflex artery.

FlNAL DlAGNOSlS

Wellens syndrome.

TREATMENT

Owing to frequent angina pectoris and the ECG pattern of Wellens syndrome, the patient was administered aspirin (300 mg), clopidogrel (300 mg), and atorvastatin (40 mg) for dual-loading antiplatelet and statin therapy, followed by percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI). Subsequently, a 3.0 mm × 23 mm drug-eluting stent was successfully implanted into the proximal LAD.

OUTCOME AND FOLLOW-UP

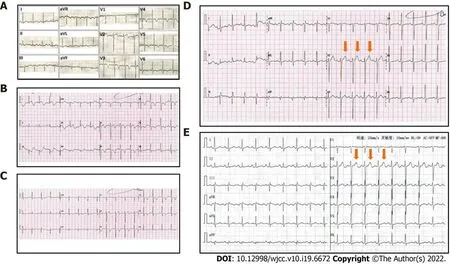

The patient’s chest pain fully resolved after the PCI. Postoperative ECGs demonstrated inverted or biphasic T-waves at the extensive anterior precordial leads on the day of PCI (Figure 3A), and 1 and 2 d after PCI (Figure 3B and C, respectively), but normal T-waves 3 d after PCI (Figure 3D). His ECGs recorded no subsequent ischemic ST-T-wave changes. Postoperative transthoracic echocardiography indicated a left ventricular ejection fraction of 69%. The patient’s ECG records at 1 (Figure 3E), 3, and 6 mo after hospital discharge were all normal, and he experienced no further chest pains during followup.

DlSCUSSlON

An increasing number of special ECG patterns are found to correlate highly with acute myocardial infarction (AMI), and these ECG patterns are even capable of predicting the exact site of the culprit lesions. For example, ST-segment elevation in lead aVR indicates an acute left main coronary artery occlusion[3] and leads V2 and aVL ST elevations indicate occlusion of the first diagonal artery[4]. Besides, de Winter pattern[5], Wellens syndrome, and Aslanger syndrome[6] among other ECG patterns, also draw the attention of clinic practitioners. However, due to the absence of classic ECG manifestations of AMI, identification of high-risk patients with these special ECG patterns is often delayed. In this paper, we report a case of Wellens syndrome to emphasize its value in the early identification of AMI.

Wellens syndrome, a specific ECG manifestation in high-risk patients with unstable angina pectoris, has an incidence of 0.1%[7] and a prevalence of 14%-18%[8] in patients with unstable angina pectoris. A history of angina, inverted or biphasic T-waves in the precordial ECG leads during the pain-free period, and little or no abnormality in cardiac biomarkers are key diagnostic indicators[9]. Another feature of Wellens syndrome is that in the presence of angina, the inverted or biphasic T-waves develop into positive T-waves[10], called pseudo-normalized T-waves[2] with an unknown mechanism. Additionally, Wellens syndrome is categorized into type A (biphasic) and type B (inverted) T-waves, which account for approximately 75% and 25% of the cases, respectively.

Previous studies have documented common etiologies of Wellens syndrome, including myocardial bridge[11], Tako-Tsubo cardiomyopathy[12], pulmonary embolus[13], and coronary spasm caused by drug abuse[14]. The pathophysiological mechanism underlying the characteristic T-wave changes in Wellens syndrome is debatable. Some studies have suggested that dynamic T-wave changes are caused by myocardial stunning or ventricular systolic dysfunction[15,16], whereas others have suggested that the pathophysiology is myocardial edema rather than myocardial dysfunction[17]. However, these studies have not clarified the mechanisms underlying the inverted or biphasic T-waves during the painfree period, or the positive T-waves in the presence of angina.

Figure 1 Preoperative electrocardiogram findings in a patient presenting with chest pain and exertional dyspnea. A and B: The electrocardiograms (ECGs) are normal in the presence of angina; C: The ECG shows inverted or biphasic T-waves in the absence of angina; D: The ECG at admission in the absence of angina showing sinus tachycardia and T-wave changes.

Figure 2 Coronary angiography findings in a patient presenting with chest pain and exertional dyspnea. A and B: Coronary angiography (CAG) showing 90%-95% localized stenosis of the proximal left anterior descending (LAD) artery; C: CAG showing recovery of LAD flow after the percutaneous coronary intervention.

Wellens syndrome plays an important role in the early recognition of the pre-infarction state and severe stenosis of the LAD. A study conducted by Haineset al[18] indicated that the Wellens syndrome ECG pattern has a sensitivity of 69%, specificity of 89%, and positive predictive value of 86% for significant LAD stenosis. Among patients with Wellens syndrome that accepted medicinal treatment alone, 75% reportedly developed myocardial infarction within 8.5 d[1]. Once Wellens syndrome is diagnosed, patients should undergo primary PCI, instead of exercise stress testing. In patients with Wellens syndrome, exercise stress testing induces AMI, malignant arrhythmias, or even sudden death[19].

Figure 3 Electrocardiogram findings after percutaneous coronary intervention in a patient presenting with chest pain and exertional dyspnea. A: Postoperative electrocardiograms (ECGs) showing inverted or biphasic T-waves at the extensive anterior precordial leads on the day of percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI); B: 1 d after PCI; C: 2 d after PCI; D: Postoperative ECGs showing normal T-waves on 3 d after PCI; E: 30 d after PCI.

The ECGs in our patient showed positive T-waves during angina, but inverted or biphasic T-waves when angina was relieved, thereby meeting the diagnostic criteria of Wellens syndrome. CAG showed a 90%-95% localized stenosis of the proximal LAD, which indicates that critical myocardial ischemia was present in this patient before he underwent PCI. Additionally, the patient’s angina resolved fully after PCI, and the T-waves normalized. These findings imply that the abnormal T-waves associated with Wellens syndrome resulted from severe fixed coronary stenosis, which could be repaired by PCI.

Regarding the evolution of the inverted or biphasic T-waves to positive T-waves during angina, we believe this was caused by the aggravation of myocardial ischemia. It is well known that flat, biphasic, or inverted T-waves are ECG manifestations of endocardial ischemia, whereas tall and symmetrical positive T-waves are features of transmural injury in the hyperacute phase of ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI). For patients with Wellens syndrome, coronary stenosis, coronary spasm, unstable plaque rupture, or myocardial oxygen supply-demand imbalance, would aggravate myocardial ischemia and even cause acute epicardial injury, resulting in angina attacks and abnormal Twaves becoming positive or pseudo-normalized. We found that the T-waves on this patient’s ECGs during angina attacks, which were previously considered pseudo-normalized, were higher and more symmetrical than the normal T-waves on ECGs at 3 and 30 days after PCI. Since Wellens syndrome has the potential to develop into AMI, we propose that the pseudo-normalized T-waves of Wellens syndrome in the presence of angina probably reflect its deterioration into the hyperacute phase of STEMI.

One limitation of this study is that we did not obtain enough cases to quantify and compare the symmetry of the T-waves in patients with Wellens syndrome before and after PCI.

CONCLUSlON

Our report demonstrates the ECG manifestations of Wellens syndrome before and after PCI, and during long-term postoperative follow-up, which were not considered in previous studies. The follow-up ECGs indicate that PCI can resolve the abnormal T-waves of Wellens syndrome. The abnormal T-waves during the pain-free period of Wellens syndrome likely result from endocardial ischemia based on significant coronary stenosis, while the pseudo-normalized T-waves reflect epicardial ischemia caused by stenosis aggravation. Without timely and effective treatment, pseudo-normalized T-waves are likely to develop into ST-segment elevation. Further studies are required to quantify and compare the symmetry of the T-waves in a larger number of patients with Wellens syndrome before and after PCI.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The author would like to express their gratitude to Dr. Yang LL and Dr. Yu X for their help on the revise of this paper.

FOOTNOTES

Author contributions:Tang N, Li YH and Kang L reviewed the literature and contributed to manuscript drafting; Li R and Chu QM analyzed and interpreted the electrocardiogram and coronary angiography findings; Chu QM was responsible for the revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content; all authors issued final approval for the version to be submitted.

lnformed consent statement:Informed written consent was obtained from the patient for publication of this report and any accompanying images.

Conflict-of-interest statement:The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

CARE Checklist (2016) statement:The authors have read the CARE Checklist (2016), and the manuscript was prepared and revised according to the CARE Checklist (2016).

Open-Access:This article is an open-access article that was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution NonCommercial (CC BYNC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is noncommercial. See: https://creativecommons.org/Licenses/by-nc/4.0/

Country/Territory of origin:China

ORClD number:Na Tang 0000-0002-0503-7174; Yi-Hua Li 0000-0002-9056-2386; Liang Kang 0000-0002-5042-8553; Rong Li 0000-0001-5771-1178; Qing-Min Chu 0000-0002-1144-5211.

S-Editor:Yan JP

L-Editor:A

P-Editor:Yan JP

World Journal of Clinical Cases2022年19期

World Journal of Clinical Cases2022年19期

- World Journal of Clinical Cases的其它文章

- Hem-o-lok clip migration to the common bile duct after laparoscopic common bile duct exploration: A case report

- Preliminary evidence in treatment of eosinophilic gastroenteritis in children: A case series

- Identification of risk factors for surgical site infection after type II and type III tibial pilon fracture surgery

- Sustained dialysis with misplaced peritoneal dialysis catheter outside peritoneum: A case report

- Delayed-onset endophthalmitis associated with Achromobacter species developed in acute form several months after cataract surgery: Three case reports

- Diagnostic accuracy of ≥ 16-slice spiral computed tomography for local staging of colon cancer: A systematic review and meta-analysis