Virological and histological evaluation of intestinal samples in COVID-19 patients

Dajana Cuicchi, Liliana Gabrielli, Maria Lucia Tardio, Giada Rossini, Antonietta D'Errico, Pierluigi Viale, TizianaLazzarotto,Gilberto Poggioli

Abstract

Key Words: COVID-19; SARS-CoV-2; Intestinal infection; Intestinal samples; Intestinal tropism; Rectal samples

INTRODUCTION

Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus-2 (SARS-CoV-2) is the pathogen responsible for pandemic coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19). It is a highly contagious virus which primarily affects the respiratory tract, typically causing symptoms, such as fever, dry cough and dyspnea, up to respiratory failure and death[1]. Nevertheless, the lungs are not the only target organs of the virus.Several studies have suggested that the intestinal tract could represent an additional tropism site for SARS-CoV-2[2]. Gastrointestinal (GI) symptoms, including diarrhea, nausea, vomiting, anorexia and abdominal pain are present in a substantial number of COVID-19 patients; the incidence can vary from 10% to 55%[3-6]. Many studies have reported that viral nucleic acids are detected in stool samples of COVID-19 patients with rates varying from 15.3% to 66.7%[7-11]. Viral receptor angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 (ACE2) and transmembrane protease serine-type 2 are highly expressed in the epithelial cells of the intestinal mucosa[7,12]. Moreover, some studies have demonstrated that SARS-CoV-2 virus can actively infect and replicate in human enteroids andin vitromodels of human intestinal epithelium[13,14]. These observations have collectively suggested that enteric infection can occur in patients with COVID-19. However, more robust evidence is limited. The detection of viral RNA in GI tissue samples or the isolation of the virus in stool samples have been reported in studies which enrolled only a limited number of cases[15-18]. In the present study, a greater number of intestinal mucosal samples from COVID-19 patients (as compared to previous studies) were analyzed, with the primary objective of detecting SARS-CoV-2 RNA and evaluating histological features.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

The COVID-19 patients hospitalized at IRCCS Sant’Orsola Hospital, University of Bologna, Bologna,Italy from June 2020 to March 2021 were evaluated for enrollment in a monocentric trial. SARS-CoV-2 infection was diagnosed at admission using real-time reverse transcriptase-polymerase chain reaction(RT-PCR) on pharyngeal swab specimens. The study was approved by the local hospital ethics committee and informed consent was obtained from all of the patients.

Inclusion/exclusion criteria

The study population was composed of two groups of adult patients (≥ 18 years of age) hospitalized for COVID-19. In the first group (biopsy group), patients were eligible for inclusion if they had mild to moderate disease (mild: Only mild symptoms with no radiological signs; moderate: Characterized by fever, respiratory symptoms and radiological signs of pneumonia)[19] and if they agreed to have a rectal biopsy; in the second group (surgical specimen group), patients were eligible for inclusion if they underwent intestinal resection during index hospitalization.

In the biopsy group, patients who had severe (dyspnea, respiratory frequency ≥ 30 breaths per minute, blood oxygen saturation ≤ 93%, partial pressure of arterial oxygen to fraction of inspired oxygen ratio < 300, and/or lung infiltrates > 50% within 24-48 h) and critical (respiratory failure, septic shock,and/or multiple organ dysfunction or failure) disease[19], contraindications to rectal biopsies (anticoagulant therapy with the exception of therapy with low molecular weight heparin and antiplatelet therapy), rectal disease (e.g.,chronic inflammatory disease and proctitis), previous abdominoperineal resection, recent anal surgery, anal stenosis or anal pain were excluded. In the surgical specimen group,those patients undergoing surgical treatment, cases without intestinal resection were excluded.

Interventions and design overview

Patients enrolled in the biopsy group were asked to collect a stool sample and undergo anoscopy with biopsy during their hospital stay. The anoscopy was performed at the bedside with the patient in the left lateral decubitus position using a disposable anoscope 18 mm diameter, lubricated with an anesthetic gel. During each anoscopy, 2 biopsies were performed at different sites of the rectal mucosa for viral RNA detection and stored, one in RNA Preservation Medium (RNAlaterTMStabilization Solution,Thermo Fisher Scientific, United States) and then fresh frozen, and one in 10% buffered formalin. The biopsy specimen fixed in formalin was subsequently paraffin embedded, cut into 4-μm-thick sections and then stained with hematoxylin and eosin. Multiple sections were obtained to assess the extent of the inflammation. Serial paraffin sections, 3-μm-thick, mounted on precoated slides were processed using standardized automated procedures with prediluted anti-CD68 antibody (clone PG-M1; DBS,Pleasanton, CA). The stool samples and all the biopsies were tested for the detection of SARS-CoV-2 RNA using real-time RT-PCR. The extraction of nucleic acids, reverse transcription reaction and realtime PCR amplification were performed using a SARS-CoV-2 ELITe MGB®Kit (ELITechGroup, Italy) on an ELITeInGenius®instrument. The assay detects the RNA of two SARS-CoV-2 specific genomic regions: RdRp gene and ORF8 gene. The tissue viral load was reported as number of copies/microgram RNA. The limit of detection of the test is 2 copies/reaction (10 copies/microgram RNA). Positive results below the lower limit of quantification (5 copies/reaction) were reported as < 25 copies/microgram RNA.Qualitative data were provided for the fecal samples.

Patients enrolled in the surgical specimen group were asked for consent in order to take a tissue sample from the surgical specimen to identify the presence of both inflammatory cells infiltrated and virus SARS-CoV-2 RNA using the same methodology described above. For each patient, data were collected regarding sex, age, comorbidities, disease severity, symptoms on admission, radiological features and clinical outcomes.

Outcomes

The primary aim was to evaluate the presence of SARS-CoV-2 RNA in intestinal mucosa samples using real-time RT-PCR. The secondary aims were to detect both SARS-CoV-2 RNA in stool samples using RT-PCR and the inflammatory state in all tissue samples.

Statistical analysis

Sample size analysis was not carried out due to the exploratory nature of the study. Statistical analysis was carried out using SPSS 20 software (SPSS Inc, Chicago, IL). Continuous data were expressed as means ± SDs (for data with normal distribution), or median and range (for data with nonnormal distribution); discrete data were expressed as percentages. The descriptive analyses were carried out using parametric methods, depending on the distribution of the variables under examination. Variables between the 2 groups were compared using the following tests as appropriate:t-test and Fisher’s test.The differences were considered statistically significant for values of < 0.05.

RESULTS

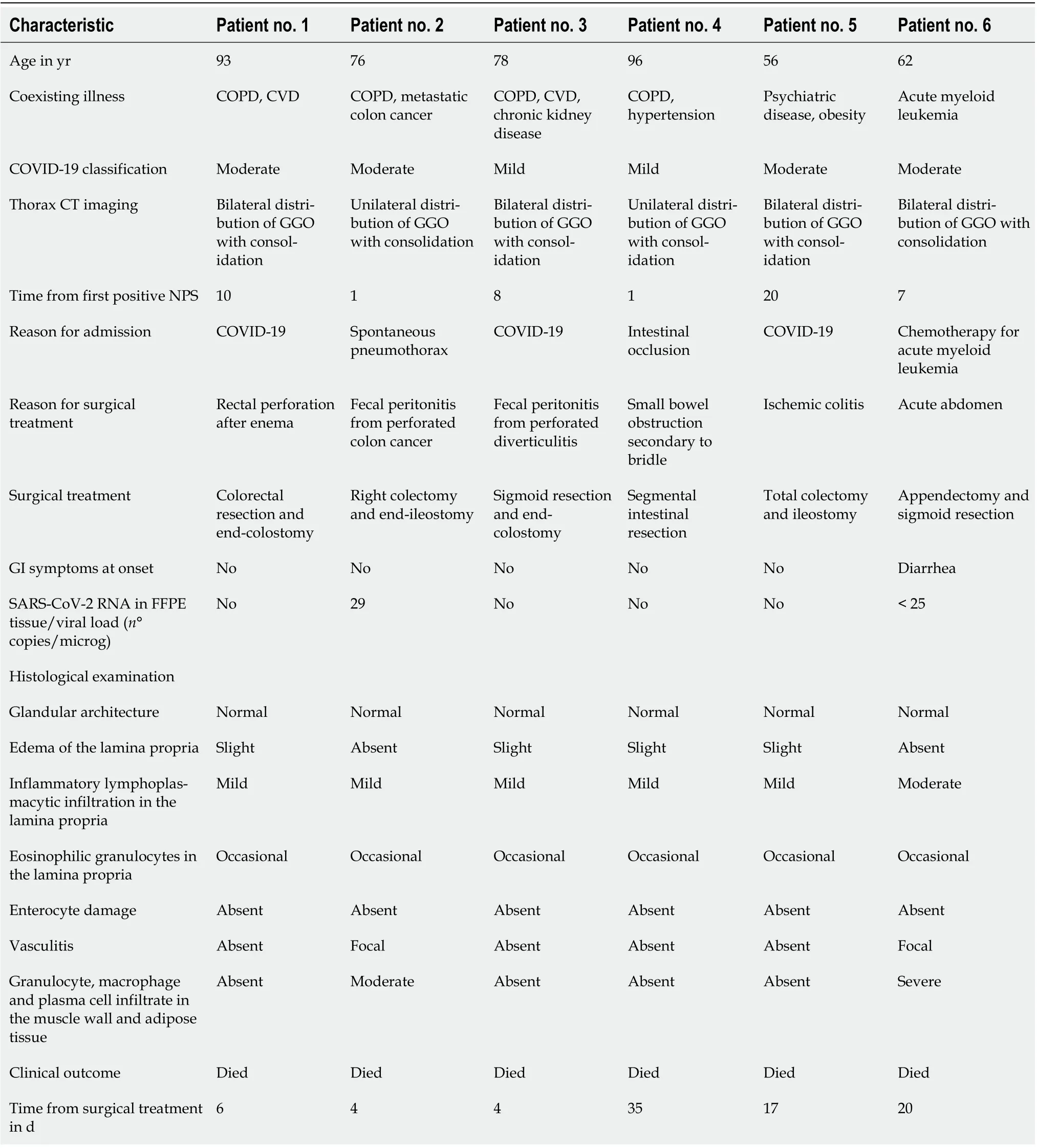

From June 2020 to March 2021, 957 patients hospitalized for confirmed COVID-19 were screened. The diagram in Figure 1 shows the flow of participants in the trial. The biopsy group consisted of 30 patients and the surgical specimen group had 6 patients. The clinical characteristics of the patients in both groups are shown in Tables 1 and 2. In the biopsy group, GI symptoms were present in 19 patients(63.3%). Diarrhea was the most common GI symptom; it was reported in 14 cases (73.7%), anorexia in 8 cases (42.1%), nausea and vomiting in 7 cases (36.8%) and abdominal pain in 4 cases (21.0%). There was no statistically significant difference in the general demographics or clinical outcomes between patients with and without GI symptoms (Table 1); SARS-CoV-2 RNA was detected in the stool in 36.4% of the patients with GI symptoms and in 66.7% of those without GI symptoms. Nevertheless, the number of positive fecal cases did not show significant difference between the two groups. Considering only patients who had diarrhea on admission, viral RNA was found in half of the fecal samples examined.Overall, SARS-CoV-2 RNA was detected in fecal samples in 6 cases out of 14 cases examined (42.9%).The greatest number of positive cases was found in the fecal samples collected in the 2ndwk after the first positive nasopharyngeal swab (NPS) (3/3, 100%), 2 cases in the 1stwk (2/5, 40%) and the remaining case in the 3rdwk (1/4, 25%). There was no significant difference in time interval between sampling and the first positive NPS in positive and negative viral RNA fecal samples (9.0 ± 4.6vs16.4 ± 14.7 respectively,P= 0.26). Viral RNA was not detectable in any of the 53 rectal biopsies performed. The histological examination of the rectal samples showed that the mucosal epithelium of the rectum did not have any major damage in patients with and without GI symptoms. The glandular architecture was always normal.In no case was there any enterocyte damage. Moreover, microscopy revealed slight expansion of the lamina propria by moderate edema in 26 cases out of 30 (86.7%) and an inflammatory lymphoplasmacytic infiltration in the lamina propria, varying from mild to moderate, in 28 and 2 cases(93.3% and 6.7%), respectively. There was no difference in inflammatory infiltrates in patients with and without GI symptoms (Table 1). Rare eosinophilic and neutrophil granulocytes were identified in the lamina propria in 20 and 2 cases (66.7% and 6.7%), respectively.

In the surgical specimen group, all patients underwent emergency intestinal resection (Table 2). Three patients were hospitalized for COVID-19 symptoms and, 8-20 d after the first positive NPS, underwent bowel resection for iatrogenic perforation of the rectum, diverticular perforation and ischemic colitis,respectively. One patient was hospitalized for intestinal obstruction secondary to bridles and underwent segmental resection of the small intestine within 1 d after a positive pharyngeal swab for SARS-CoV-2.One patient with plurimetastic colon cancer (liver, lung, peritoneum and brain), during hospitalization for a spontaneous pneumothorax developed symptoms of COVID-19 and, soon after, had an intestinal perforation for which the patient underwent a right hemicolectomy. The remaining patient affected by acute myeloid leukemia developed COVID-19 symptoms while hospitalized for chemotherapy; a week later, the patient underwent an appendectomy and colonic resection for peritonitis secondary to an inflammatory mass englobing the appendix and the sigmoid colon. All the patients died during hospitalization. SARS-CoV-2 RNA was detected in 2 cases out of 6 (33.3%). In both cases, the virus RNA was positive in the colonic tissue of the 2 patients with active neoplastic disease. In both cases, the viral load was very low. In one intestinal specimen, the viral load was less than the limit of quantification of the test (< 25 copies/microg RNA) and, in the second, it was 29 copies/microgr RNA. Histological examination of the apparently healthy tissue of all the cases showed normal glandular architecture, no enterocyte damage, a slight expansion of the lamina propria by edema and inflammatory lymphoplasmacytic infiltration in the lamina propria varying from mild to moderate. However, in the two cases positive for viral RNA, histological examination also pointed out abundant macrophages, granulocytes and plasma cells infiltrating the muscular layer, and adipose tissue, focal vasculitis and some macrophages in the vascular lumen (Figures 2A and B).

Table 1 Baseline characteristics of the biopsy group

DISCUSSION

In the present study, SARS-CoV-2 RNA was identified in only two cases out of the 59 intestinal samples(3.4%). In both cases the viral load was very low; the intestinal samples consisted of colonic tissue of patients with active neoplastic disease (a patient with acute myeloid leukemia who was receiving immunosuppressive therapy and a patient with metastatic colon cancer), and there was a nosocomial transmission of SARS-CoV-2. Interestingly, in the biopsy group, two patients had previously undergone surgery for cancer (prostate and cervix) and in both cases, no viral RNA was identified in the rectal samples. Several studies have suggested that people with neoplastic disease are more likely to contract COVID-19 and to develop more severe disease or die from it than the general population. A recent systematic review on COVID-19 patients with active malignancy, defined as current malignant disease or treatment for malignancy within the last 12 mo, showed that cancer constitutes a co-morbidity in 2.6% [95% confidence interval (CI): 1.8%-3.5%,I2: 92.0%] of hospitalized COVID-19 patients and that the pooled in-hospital mortality risk was 14.1% (95%CI: 9.1%-19.8%,I2: 52.3%)[20]. Nahshonet al[21]suggested a severe clinical course of 50.6% and a mortality rate of 34.5% in COVID-19 patients with cancer. The worst COVID-19 outcomes include acute respiratory distress syndrome, septic shock, acute myocardial ischemia and death[22]. These severe events occurred more frequently in patients with stage IV cancer as compared to those with non-stage IV cancer (70.0%vs44.4%, respectively) and if the last antitumor treatment was within 14 d (hazard ratio = 4.079, 95%CI: 1.086-15.322,P= 0.037)[22]. The pathogenesis of severe COVID-19 in cancer patients may be due to the aggravation of inflammatory cytokine storms, the imbalance of immune responses, and multiple organ damage[23]. In a multicenter retrospective cohort study on 232 patients with cancer and 519 statistically matched patients without cancer, Tianet al[23] identified elevated levels of interleukin (IL)-6, tumor necrosis factor α (TNF-α) and N-terminal pro-B-Type natriuretic peptide (NT-proBNP) and a reduced level of CD4+T cells and albumin-globulin ratio as risk factors of COVID-19 severity in patients with cancer. Similarly, in a retrospective cohort study which included 2052 patients hospitalized with COVID-19 (cancer,n= 93;non-cancer,n= 1959), Caiet al[24] reported that immune dysregulation was an important feature in cancer patients with COVID-19, which might account for their poorer prognosis; they found that COVID-19 patients with cancer had ongoing and significantly elevated inflammatory factors and cytokines (C-reactive protein, procalcitonin, IL-2 receptor, IL-6, IL-8) as well as a decreased number of immune cells (CD8 + T cells, CD4 + T cells, B cells, nature killer cells, T-helper and T- suppressor cells)than those without cancer. In patients with weakened immune systems, SARS-CoV-2 could infect vascular epithelial cells and organs, such as the lungs, heart, kidneys, liver, and intestine, expressing high levels of ACE2[25]. Autopsy data have reported viral infection in several organs, indicating hematogenic spread of the virus[26,27]. Moreover, serum SARS-CoV-2 nucleic acid (RNAemia) was associated with COVID-19 severity [odds ratio (OR) = 5.43, 95%CI: 3.46-8.53], increased risk of multiorgan failure (OR = 7.33, 95%CI: 2.46-21.88) and mortality (OR = 11.07, 95%CI: 5.60-22.88)[28].Notably, viral RNA was undetectable in any of 53 rectal biopsies performed on the 30 patients hospitalized for moderate COVID-19 (biopsy group). The inability of the authors to detect viral RNA in the rectal samples contrasted with some data which have identified SARS-CoV-2 in intestinal samples[8,9].Xiaoet al[8] evaluated the viral nucleocapsid protein in the GI tissues of a COVID-19 patient who developed severe respiratory distress and an upper GI bleed. At endoscopy, they observed mucosal damage in the esophagus and found viral nucleocapsid protein in the cytoplasm of gastric, duodenal,and rectal glandular epithelial cells with immunofluorescent staining[10]. Linet al[9] detected SARSCoV-2 RNA at endoscopy in esophageal, gastric, duodenal, and rectal specimens in 2 out of 6 COVID-19 patients having GI symptoms. In this study, the presence of viral RNA in the GI tissue was also associated with severe disease; in fact, SARS-CoV-2 RNA was found in the samples of 2 patients with severe disease but not in those of 4 patients with non-severe disease[9]. Therefore, although the authors’failure to detect SARS-CoV-2 in the rectal samples could have been due to the mild disease course of the cases selected, the possibility that the viral load was below the detection limit of their RT-PCR assay cannot be excluded. This could justify the presence of a mild to moderate inflammatory infiltrate in the lamina propria in all the rectal samples at histological examination. In fact, plasma cells, lymphocytes,and granulocytes can migrate to the extravascular space to reach the possibly infected tissues. These findings are in line with the low number of endoscopic and histological examinations of intestinal samples of COVID-19 patients which showed inflammatory infiltration in the lamina propria.Endoscopy and biopsy samples of the esophagus, stomach, duodenum and rectum were taken from a 78-year-old patient with COVID-19 who showed symptoms of upper GI bleeding. Numerous infiltrating plasma cells and lymphocytes with interstitial edema were found in the lamina propria of the stomach, duodenum and rectum of this patient[8]. In a surgical rectal specimen obtained during the incubation period in a COVID-19 patient with rectal adenocarcinoma, histological examination showed prominent lymphocytes and macrophages infiltrating the lamina propria without significant mucosal damage. T lymphocytes and macrophages were found to be more numerous than B lymphocytes in the lamina propria[29].

Six patients out of the 14 cases examined (42.9%) tested positive for SARS-CoV-2 RNA in the stool.Multiple studies have reported the positive detection of viral nucleic acids in the fecal samples of COVID-19 patients, finding rates varying from 15.3% to 66.7%[6,14]. In a meta-analysis, the authorsshowed that viral RNA may be present in the feces in 48.1% of patients[30]. The mechanism of diarrhea in patients with COVID-19 is still largely unknown. Various etiopathogenetic hypotheses have been advanced to explain the occurrence of diarrhea in COVID-19 patients including alterations in gut microbiota, osmotic diarrhea due to malabsorption or inflammation, release of virulent proteins or toxins, and viral-induced intestinal fluid and electrolyte secretion by activation of the enteric nervous system[31,32].

Table 2 Baseline characteristics of the surgical specimen group

Currently, the exact mechanism of intestinal involvement in COVID-19 is not yet well understood.Intestinal epithelial cells could be primarily infected by SARS-CoV-2viathe oral-fecal route or SARSCoV-2 may invade the enteric cells after respiratory infectionvialympho hematogenic spread. As COVID-19 is also associated with the involvement of different organs and systems, such as the liver,kidneys, heart, blood, and nervous system; it has been hypothesized that in severe COVID-19 patients and in those with compromised immunity, SARS-CoV-2 has not been successfully eradicated and can spread from the lungs to target organs, such as the intestine[33]. Although the present data are unable to support the observations suggesting that enteric infection can occur in COVID-19 patients, in the two cases positive for viral RNA, histological examination showed an inflammatory infiltrate characterized by the presence of macrophages, granulocytes, plasma cells, and focal vasculitis. Thus, it could be hypothesized that in these cases, there were both a direct viral infection and immune hyperactivation.Hyperactivation of the immune system in response to infection can cause severe complications and organ damage. The host immune response is thought to play a vital role in the pathogenesis of COVID-19[34-36]. The present study has several limitations. The biopsies were performed only in the rectum of patients with moderate COVID-19. On the other hand, due to the high risk of viral spreading during endoscopic procedures, it is difficult to obtain samples from the gastric, intestinal and colic mucosa in patients who do not complain of GI symptoms, especially in cases of severe illness. Moreover, it is not possible to exclude that the two positive colon samples could be contaminated by SARS-CoV-2 positive stool or blood. Another limitation of the present study was its observational nature which made it difficult to identify the causes of the observed phenomena. Nonetheless, the detection of the viral RNA observed and the inflammatory cell infiltration to the colonic tissue of patients with active cancer could serve as hypothesis generators, leading to the analyzing of more comprehensive autopsy or surgical specimens in order to assess the potential link between SARS-CoV-2 and enteric infections in this population. The strengths of this study include the use of RT-PCR which is the gold standard for detecting SARS-CoV-2 infection. Moreover, the rectal biopsies were performed in two different sites and stored in both RNA preservation medium and in 10% buffered formalin to reduce the risk of false negatives.

CONCLUSION

SARS-CoV-2 RNA was found in only a small percentage of the intestinal samples analyzed (3.4%).Nevertheless, more comprehensive autopsy or surgical specimens are needed to provide histological evidence of intestinal infection.

ARTICLE HIGHLIGHTS

FOOTNOTES

Author contributions:Lazzarotto T and Poggioli G contributed equally to this work. Cuicchi D, Lazzarotto T, D’Errico A and Poggioli G participated in the conceptualization and design of the study; Cuicchi D collected data and carried out the initial analyses; Cuicchi D, Gabrielli L and Tardio ML drafted the initial manuscript; Gabrielli L and Rossini G carried out the virological evaluation; Tardio ML, D’Errico A and Poggioli G carried out the histological evaluation;D’Errico A, Poggioli G and Lazzarotto T made substantial contributions to all aspects of the writing of the manuscript, which included contribution to conception, design, analysis and interpretation of the article; Lazzarotto T contributed to the review and revision of the manuscript; Poggioli G interpreted data, reviewed and revised the manuscript, and supervised and provided mentorship throughout all stages of the project and writing of the manuscript; and all authors approved the final version to be submitted.

Institutional review board statement:The study was reviewed and approved by the Institutional Review Board of the Azienda Ospedaliero-Universitaria di Bologna, Italy (Approval No. 2257/2020).

Informed consent statement:All study participants, or their legal guardian, provided informed written consent prior to study enrollment.

Conflict-of-interest statement:All the authors report having no relevant conflicts of interest for this article.

Data sharing statement:Technical appendix, statistical code, and dataset available from the corresponding author at dajana.cuicchi@aosp.bo.it. Participants gave informed consent for data sharing in anonymized form.

STROBE statement:The authors have read the STROBE Statement-checklist of items, and the manuscript was prepared and revised according to the STROBE Statement-checklist of items.

Open-Access:This article is an open-access article that was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution NonCommercial (CC BYNC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is noncommercial. See: https://creativecommons.org/Licenses/by-nc/4.0/

Country/Territory of origin:Italy

ORCID number:Dajana Cuicchi 0000-0002-1504-4888; Pierluigi Viale 0000-0003-1264-0008.

S-Editor:Wang JJ

L-Editor:Filipodia

P-Editor:Wang JJ

World Journal of Gastroenterology2022年44期

World Journal of Gastroenterology2022年44期

- World Journal of Gastroenterology的其它文章

- Comment on “Prognostic value of preoperative enhanced computed tomography as a quantitative imaging biomarker in pancreatic cancer”

- Randomized controlled trial to evaluate the efficacy and safety of fexuprazan compared with esomeprazole in erosive esophagitis

- Postoperative outcomes and recurrence patterns of intermediate-stage hepatocellular carcinoma dictated by the sum of tumor size and number

- Glucagon-like peptide-2 analogues for Crohn’s disease patients with short bowel syndrome and intestinal failure

- Development of Epstein-Barr virus-associated gastric cancer: Infection, inflammation, and oncogenesis

- Machine learning insights concerning inflammatory and liver-related risk comorbidities in noncommunicable and viral diseases