Incident respiratory disease among youths using combustible tobacco,electronic nicotine products,or both: a longitudinal analysis

Dharma N. Bhatta ·Ruchi Adhikari

The use of electronic nicotine products is rapidly evolving among the United States (US) youth.Electronic nicotine products produce and deliver thousands of pulmonary toxicants and irritants different from combustible tobacco [1,2].A review of human,animal,and in vitro experimental studies suggested that electronic nicotine product aerosols can negatively affect multiple aspects of lung cellular and organ physiology,and immune function [3,4].Electronic nicotine product users are at increased risk of life-threatening hypersensitivity pneumonitis,respiratory bronchiolitis associated with interstitial lung disease,lipoid pneumonia,diffuse alveolar hemorrhage,eosinophilic pneumonia,and organizing pneumonia [5].Cross-sectional studies have reported an association between electronic nicotine product use and respiratory disorders among adolescents and youth [6–10].Despite this evidence,the long-term respiratory effects of electronic nicotine products among youth remain unclear.We assessed the association between exclusive combustible tobacco use,exclusive electronic nicotine products use,dual use,and incident respiratory disease among youth without respiratory disease at baseline.

This study analyzed the public use dataset of youth (age:12 to 17 years) sample from Population Assessment of Tobacco and Health (PATH) survey waves 4 (considered as baseline) and 5,a nationally representative,populationbased,longitudinal study to collect data on uses of tobacco products,health outcomes,risk perception,and attitudes.Wave 4 data were collected from December 2016 to January 2018,and wave 5 was collected from December 2018 to November 2019.Our analyses included individuals who were free of respiratory disease (excluded ever or past 12-month respiratory disease) at baseline.Responses to this study were reported by either parents/guardians or youths.We defined respiratory disease as a self-report of asthma,bronchitis,pneumonia,or chronic cough.

At wave 5 asthma was assessed with the question: “In the past 12 months,youth has been told by a doctor,nurse or other health professionals that he/she had asthma”;and bronchitis,pneumonia,or chronic cough was assessed with the question: “In the past 12 months,youth has been told by a doctor,nurse or other health professionals that he/she had bronchitis,pneumonia or chronic cough”.We created a composite variable of having any respiratory disease incidence(reported one or more diseases).

Self-reported any combustible tobacco (cigarettes,cigars,traditional cigars,filtered cigars,cigarillos,pipe tobacco,bidis,kreteks,or hookah) users and electronic nicotine products users at wave 4 were categorized as exclusive combustible tobacco users (ever used any combustible tobacco and never used electronic nicotine products),exclusive electronic nicotine products users (ever used electronic nicotine products and never used combustible tobacco),dual users (ever used both combustible tobacco and electronic nicotine products) and never users (never used both combustible tobacco and electronic nicotine products).Demographic variables were age,sex,race/ethnicity (Hispanic,White non-Hispanic,Black non-Hispanic,other non-Hispanic),and body mass index.

We conducted multivariable logistic regression to examine the association between combustible tobacco use,electronic nicotine products use,dual use,and incident respiratory disease,adjusting for demographic characteristics and accounting for complex survey sampling as specified in the PATH study user guide [11].As a sensitivity analysis,we included those whose exposure categorization of combustible tobacco and electronic nicotine products use was alike in waves 4 and 5.This means the exclusive combustible tobacco users,exclusive electronic nicotine products users,dual users,and never users in waves 4 and 5.We conducted all analyses in R statistical software using a“survey package”.We applied a listwise deletion method in regression analyses to handle missing data.Adjusted odds ratios (AORs) with 95% confidence intervals (CI)were calculated.

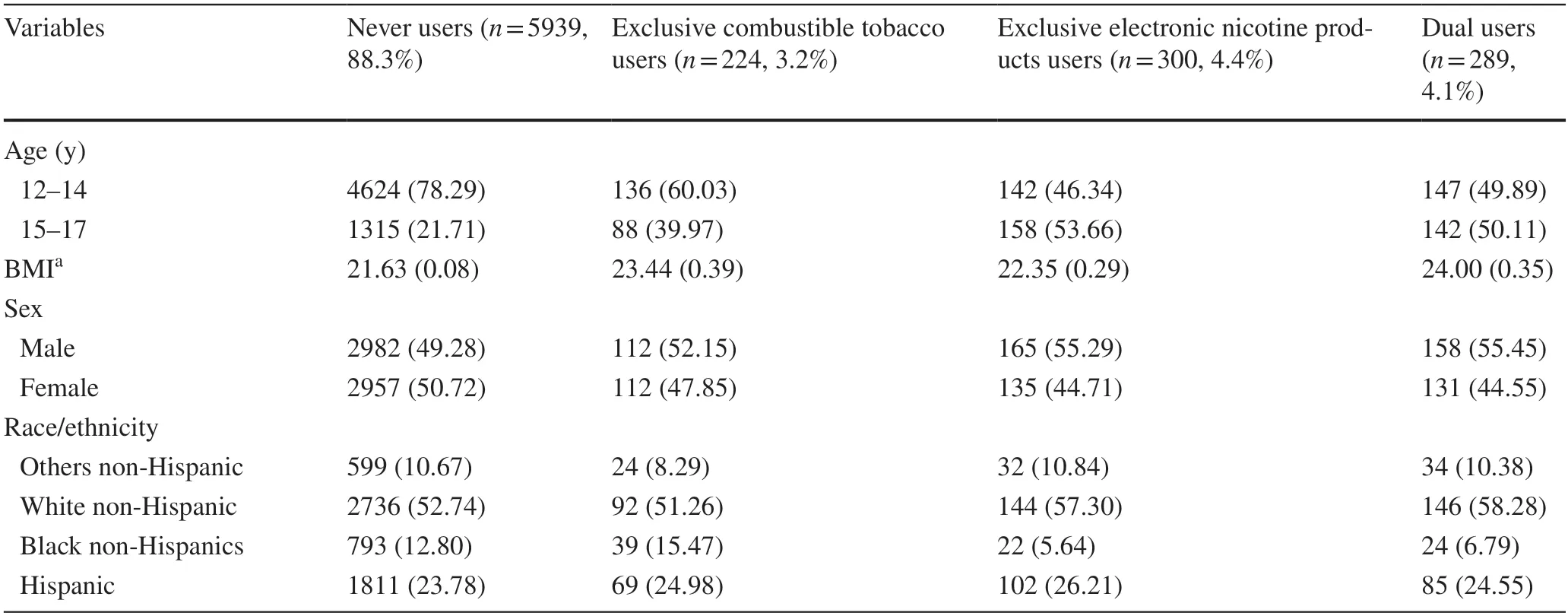

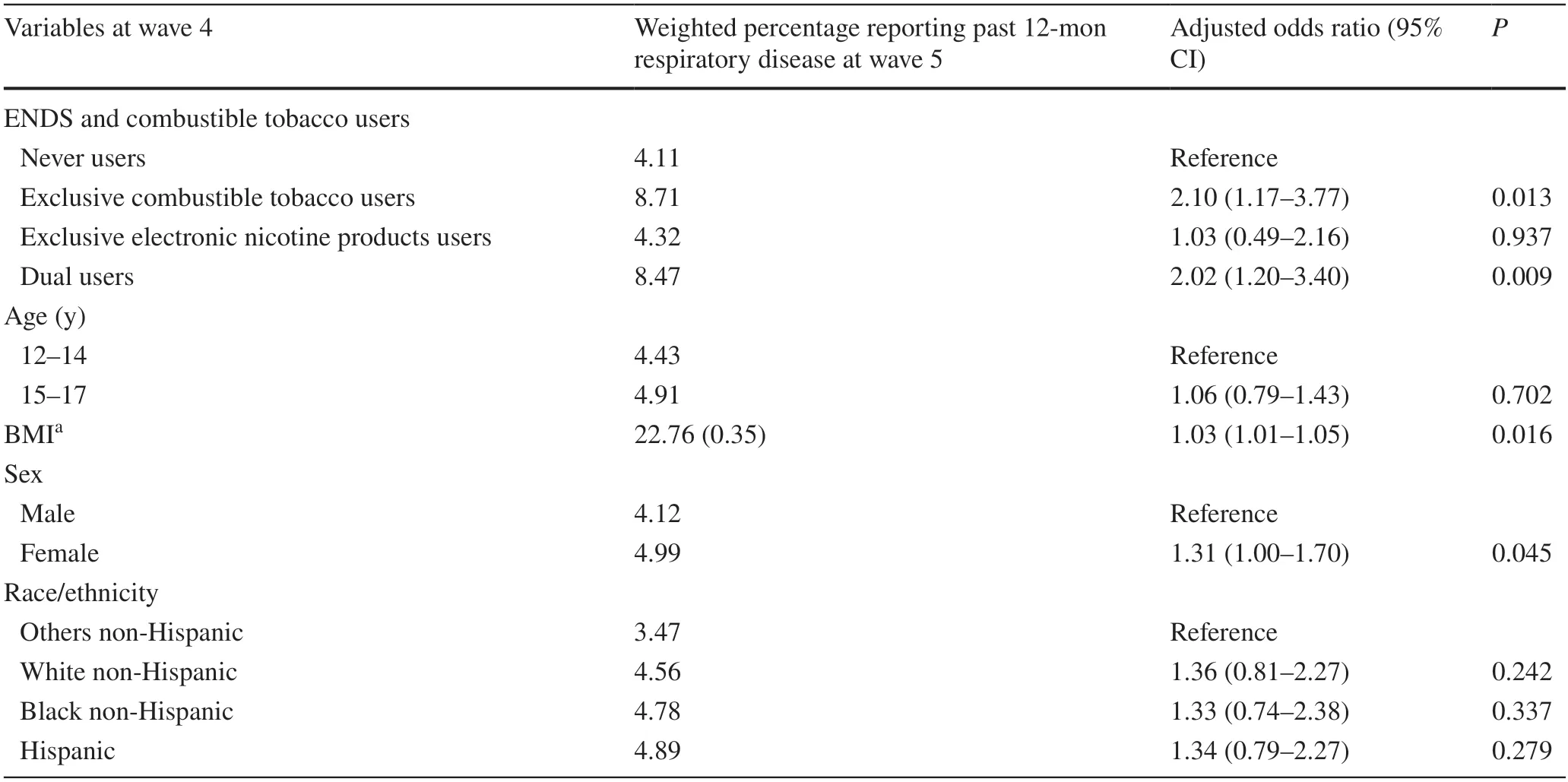

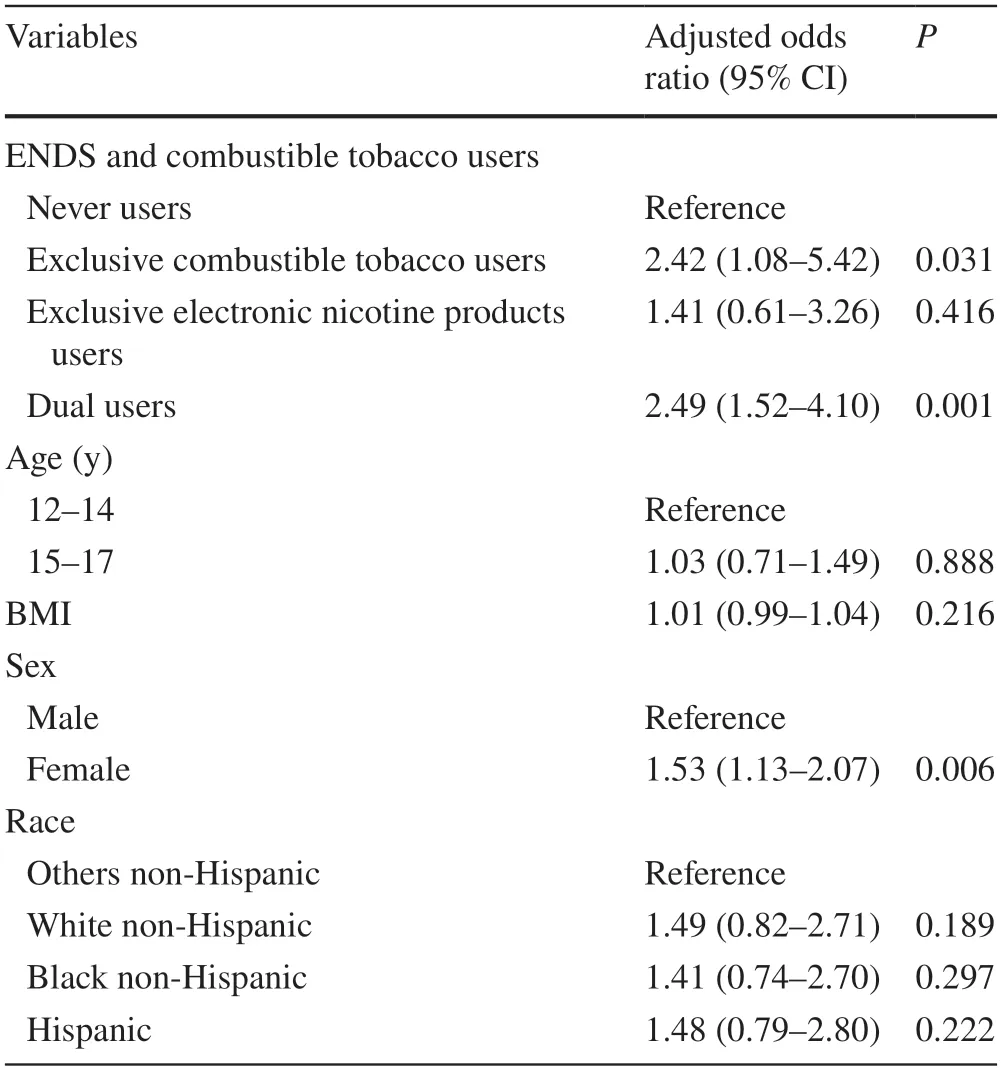

Among 6752 youths,after excluding ever or past 12-month respiratory disease at baseline,88.3% were never users,3.2% were exclusive combustible tobacco users,4.4% were exclusive electronic nicotine products users,and 4.1% were dual users (Table 1).Exclusive combustible tobacco use (AOR=2.10,95% CI=1.17–3.77),electronic nicotine products use (AOR=1.03,95% CI=0.49–2.16),and dual use of combustible tobacco and electronic nicotine products (AOR=2.02,95% CI=1.20–3.40) were more likely to be associated with an increased risk of respiratory disease incidence compared to never use any products.Point estimates for exclusive electronic nicotine products were not statistically significant (Table 2).The AOR for all the categories of exposure was increased in the sensitivity analysis (Table 3).

Table 1 Demographic characteristics stratified by electronic nicotine products and combustible tobacco users at wave 4 among those who never had the respiratory disease at wave 4

Table 2 Association between combustible tobacco or electronic nicotine products use at wave 4 and past 12-month respiratory disease at wave 5(n =6651)

Table 3 Association between combustible tobacco or electronic nicotine products use at both waves 4 and 5,and past 12-month respiratory disease at wave 5 (n =5270)

This population-based cohort study found that dual use of combustible tobacco and electronic nicotine products was associated with an increased risk of respiratory disease among youth.These results contribute to the continuing discussion about the respiratory effects of electronic nicotine product use among youth,and the findings may be helpful to pediatricians or physicians who are asked to alert young people about the risks of electronic nicotine products or dual use.

This study findings are consistent with previous research,such as existing cross-sectional epidemiological studies conducted among youth [6–10];laboratory,biological,and adult studies on adverse respiratory functions [3–5,12];and longitudinal epidemiological studies conducted among adults [13,14].Dual use of combustible tobacco and electronic nicotine products might have a synergistic interaction with lung pathology.This study’s findings are plausible based on biological and laboratory studies that indicate the potential effects of electronic nicotine products on the pulmonary system.For example,electronic nicotine products aerosols contain several respiratory irritants and toxicants that have been associated with respiratory symptoms;diacetyl and related diketone compounds or flavoring compounds have caused obstructive respiratory disease or bronchiolitis obliterans;glycerin-based oils found in e-cigarette aerosols have caused lipoid pneumonia;electronic nicotine products aerosols that increase oxidative stress could affect airway cells;electronic nicotine products aerosols that increase cytotoxic,allergen-induced airway inflammation and hyperresponsiveness could contribute to respiratory symptoms or damage to lung tissue;electronic nicotine products aerosols containing nitric oxide could be a marker of airway inflammation;electronic nicotine products aerosols contribute to the weakening of the immune system and increase susceptibility to infection [3–5,12].

It has been hypothesized that some individuals with the preexisting respiratory disease might have usedelectronic nicotine products because of the perception that they were therapeutic or less harmful than conventional cigarettes.Schweitzer et al.noted this reversecausation argument is implausible because the electronic nicotine products use among youth is higher than conventional cigarette smoking,so youth are unlikely to switch from smoking cigarettes to using electronic nicotine delivery systems [9],and studies based on meta-analysis established that the electronic nicotine products use is a gateway to tobacco smoking among youth [15–17].However,in some situations,few clinical conditions may motivate to switch from smoking tobacco to electronic nicotine products use.

The strengths of this study were randomly selected participants,prospective longitudinal follow-up,nationally representative,and a large cohort.The survey tools related to pulmonary disease [18,19] were validated against direct clinical observation and widely applied in large-scale epidemiological studies.This study excluded ever or past 12-month respiratory disease at baseline,and applied sensitivity analysis to validate the primary finding.E-cigarette and combustible tobacco use behaviors are unstable and change frequently.Those who were using e-cigarettes at baseline may have switched to combustible tobacco in subsequent waves,and the latter may have precipitated respiratory disease.To limit this misclassification,we performed sensitivity analysis controlling for time-varying exposure variables (exposure categorization of combustible tobacco and electronic nicotine products used was the same in waves 4 and 5) and we found the AOR was even stronger.However,owing to the small number of samples,the point estimates did not reach statistical significance.

This study has a few limitations.There is a chance of recall bias because we used self-reported events of smoking history without biochemical confirmation.However,it is hard to perform biochemical verification for such a large epidemiological survey.Youths with the respiratory disease could under-report these tobacco products.We were unable to control the history of tobacco product use,characteristics of electronic nicotine products,the intensity of tobacco product use,comorbidities,parental smoking habits,family history of asthma,and other several potential covariates which could affect the development of lung disease.Some respiratory conditions might appear after a long duration of tobacco product exposure which could be the possible reason for the small number of incidents of respiratory disease among youth which is why the point estimates did not reach statistical significance.Further longitudinal follow-up is required to track the impact of these products among youth.With the support of several biological and epidemiological studies findings,this study revealed that none of the exposure types (exclusive combustible tobacco use,exclusive electronic nicotine products use,or dual use) is safe for respiratory disease among youth.Youth who use electronic nicotine products have higher chances to become dual users,and the use of electronic nicotine products could have public health,clinical,economic,and policy implications.Our findings provide useful information on combustible tobacco use,electronic nicotine products use,and dual use with potential risk to help pediatricians or physicians treat and prevent tobacco-associated lung disease.

Author contributionsBDN contributed to conception and design,data analysis and interpretation,and manuscript writing.AR contributed to conception and design,interpretation,draft manuscript writing,and editing.All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

FundingNone

Data availabilityPublic use data can be obtained from https:// doi.org/10.3886/ ICPSR 36498.v13 .

Declarations

Ethical approvalWe used public use secondary data and ethical approval is not required for this study.

Conflict of interestNo financial or non-financial benefits have been received or will be received from any party related directly or indirectly to the subject of this article.The authors have no conflict of interest to declare.

World Journal of Pediatrics2022年11期

World Journal of Pediatrics2022年11期

- World Journal of Pediatrics的其它文章

- Instructions for Authors

- Third-line therapies in patients with Kawasaki disease refractory to first-and second-line intravenous immunoglobulin therapy

- A novel HNF4A mutation identified in a child with maturity onset diabetes of the young

- Neutropenia: diagnosis and management

- Integration of multiscale entropy and BASED scale of electroencephalography after adrenocorticotropic hormone therapy predict relapse of infantile spasms

- Effect of early atopic sensitization in children aged 0–2 years on the development of asthma symptoms at 9–11 years of age