Effects of amyloid precursor protein peptide APP96-110, alone or with human mesenchymal stromal cells, on recovery after spinal cord injury

Stuart I. Hodgetts, Sarah J. Lovett D. Baron-Heeris A. Fogliani Marian Sturm, C. Van den Heuvel, Alan R. Harvey

Abstract Delivery of a peptide (APP96-110), derived from amyloid precursor protein (APP), has been shown to elicit neuroprotective effects following cerebral stroke and traumatic brain injury. In this study, the effect of APP96-110 or a mutant version of this peptide (mAPP96-110) was assessed following moderate (200 kdyn, (2 N)) thoracic contusive spinal cord injury (SCI) in adult Nude rats. Animals received a single tail vein injection of APP96-110 or mAPP96-110 at 30 minutes post-SCI and were then assessed for functional improvements over the next 8 weeks. A cohort of animals also received transplants of either viable or non-viable human mesenchymal stromal cells (hMSCs) into the SC lesion site at one week post-injury to assess the effect of combining intravenous APP96-110 delivery with hMSC treatment. Rats were perfused 8 weeks post-SCI and longitudinal sections of spinal cord analyzed for a number of factors including hMSC viability, cyst size, axonal regrowth, glial reactivity and macrophage activation. Analysis of sensorimotor function revealed occasional significant differences between groups using Ladderwalk or Ratwalk tests, however there were no consistent improvements in functional outcome after any of the treatments. mAPP96-110 alone, and APP96-110 in combination with both viable and non-viable hMSCs significantly reduced cyst size compared to SCI alone. Combined treatments with donor hMSCs also significantly increased βIII tubulin+, glial fibrillary acidic protein (GFAP+) and laminin+ expression, and decreased ED1+ expression in tissues. This preliminary study demonstrates that intravenous delivery of APP96-110 peptide has selective, modest neuroprotective effects following SCI, which may be enhanced when combined with hMSC transplantation. However, the effects are less pronounced and less consistent compared to the protective morphological and cognitive impact that this same peptide has on neuronal survival and behaviour after stroke and traumatic brain injury. Thus while the efficacy of a particular therapeutic approach in one CNS injury model may provide justification for its use in other neurotrauma models, similar outcomes may not necessarily occur and more targeted approaches suited to location and severity are required. All animal experiments were approved by The University of Western Australia Animal Ethics Committee (RA3/100/1460) on April 12, 2016.

Key Words: amyloid precursor protein; cell transplantation; combination; contusion; functional recovery; mesenchymal stromal cells; neuroprotection; regeneration; spinal cord injury; tissue sparing

Introduction

Secondary degenerative changes following an initial trauma are major contributors to the extensive cell death and tissue damage, and associated loss of functional connections, that occur after spinal cord injury (SCI) (Hausmann, 2003; Hagg and Oudega, 2006). Widespread and ongoing degenerative events create a hostile injury site that is unable to support cell survival, axonal regrowth/regeneration and remyelination following injury. Any reduction in inflammatory damage and secondary degeneration may significantly improve neuronal and glial cell survival, thereby increasing tissue sparing and the preservation of functional connections at the lesion site, potentially resulting in functional and morphological improvements (Bethea and Dietrich, 2002; Alexander and Popovich, 2009; Bowes and Yip, 2014).

Many neuroprotective approaches aim to reduce host tissue damage following SCI by modulating inflammatory and immunological reactions at the lesion site, protecting neuronal and glial cells against excitotoxicity or by inhibiting apoptosis (Kwon et al., 2011; Siddiqui et al., 2015). Cationic argininerich peptides and polyarginine or arginine-rich peptides have potent neuroprotective propertiesin vitro(Meloni et al., 2014, 2015a, b; Edwards et al., 2017), andin vivothey have been shown to be protective after both permanent and transient middle cerebral artery occlusion (MCAO) stroke in rats (Meloni et al., 2015a, 2017; Milani et al., 2016, 2017). Derived from the apolipoprotein E and amyloid precursor proteins (APP) respectively, the COG1410 and APP96-110 peptides are cationic and arginine rich (Chiu et al., 2017) and also exhibit neuroprotective effects following traumatic brain injury (TBI) (Hoane et al., 2007; Laskowitz et al., 2007; Tukhovskaya et al., 2009; Kaufman et al., 2010; Jiang and Brody, 2012; Corrigan et al., 2014; Cao et al., 2016; Qin et al., 2017). The neuroprotective potential of APP has been studied in a number of central nervous system (CNS) injury models after it was identified that APP upregulation following traumatic brain injury (TBI) is associated with a significant increase in neuronal survival (Van den Heuvel et al., 1999). Further investigation of APP identified several functional regions that may contribute to its neuroprotective ability. In particular, the heparin binding site at amino acid residues 96-110 (APP96-110) was shown to have neuroprotective effects following TBI, resulting in reduced lesion volume and axonal injury, increased numbers of spared neurons, and improved functional and cognitive outcomes (Corrigan et al., 2011, 2014; Plummer et al., 2018). The APP96-110 peptide may also exert similar neuroprotective effects in other traumatic CNS injury models.

In the present study, the neuroprotective effect of APP96-110 was assessed following moderate contusive SCI in Nude rats (Hodgetts et al., 2013a, b), with animals given a single intravenous injection of APP96-110 (active) and mAPP96-110 (mutant; with reduced but not absent heparin binding ability (Corrigan et al., 2014)) peptides at 30 minutes post-SCI. Because multipotent mesenchymal stromal cells (MSCs) are anti-inflammatory and immunomodulatory (Gronthos et al., 2003; Herrmann et al., 2012; Herrmann and Sturm, 2014) and cells of this lineage have been shown to elicit beneficial effects after SCI (Tetzlaff et al., 2011; Hodgetts et al., 2013a, b), a cohort of animals also received transplantation of viable (v) or non-viable (nv) human mesenchymal stromal cells (hMSCs) at one week post-injury, to assess the effect of combined APP96-110 and hMSC treatment. Based on previous studies carried out in the brain (Van den Heuvel et al., 1999; Hoane et al., 2007; Laskowitz et al., 2007; Tukhovskaya et al., 2009; Kaufman et al., 2010; Jiang and Brody, 2012; Corrigan et al., 2014; Cao et al., 2016; Qin et al., 2017), it was hypothesised that APP96-110 will exert neuroprotective effects following SCI, leading to significantly reduced tissue damage, and improved tissue sparing and functional recovery. Combined treatment with hMSC transplantation will determine whether the altered local environment of the cell transplanted injury site provides an even better platform for the regrowth of axons after APP96-110-induced neuroprotection. This combined treatment may produce greater improvements than APP96-110 or hMSCs alone.

Materials and Methods

Experimental animals

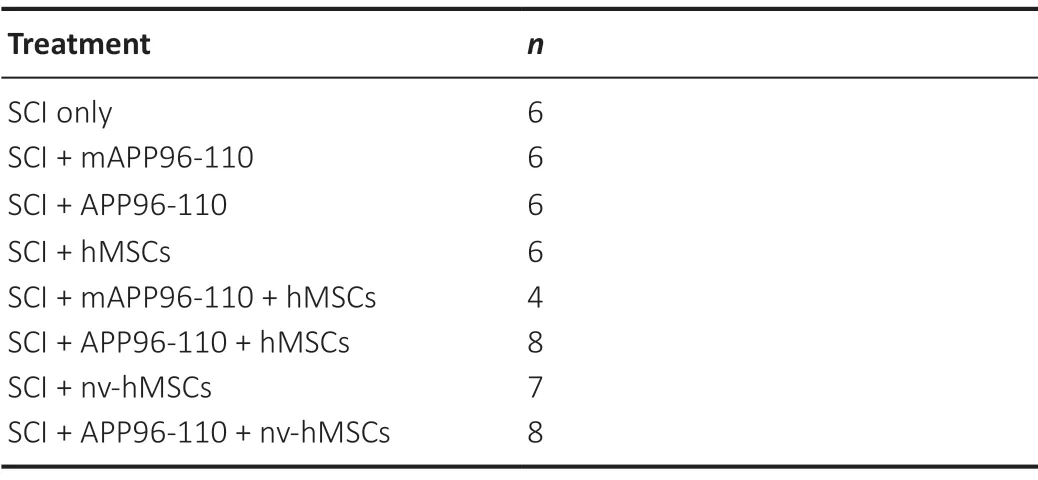

All animal work was approved by The University of Western Australia Animal Ethics Committee (RA3/100/1460, approved on April 12, 2016) and conformed to National Health and Medical Research Council (Australia) guidelines. Fifty-one adult female CBH-rnu/Arc (Athymic Nude) rats (≥ 12 weeks, body weight 140-170 g; Animal Resources Centre, Perth, WA, Australia) were used in this study, distributed randomly across 8 experimental groups (n= 4-8/group) as shown inTable 1. Animals were housed in filter top cages with absorbent bedding, with access to food and waterad libitum, on a 12-hour light-dark cycle (red lights on 1000-2200). Animals were acclimated to the holding room, handled and pre-trained on all behavioural testing apparatus daily for 2 weeks prior to SCI surgery.

Table 1 |Treatment groups and number of animals per group, sacrificed at 8 weeks post-injury

SCI

Pre-surgical buprenorphine (Temgesic, 1 μg/100 g body weight, 300 U/mL, intraperitoneal (i.p.); Reckitt Benckiser Healthcare, West Ryde, NSW, Australia) was administered 30 minutes prior to the induction of anaesthesia. Animals were anaesthetised with isoflurane (induced at 3-4% (v/v) and maintained at 1.5-2.5% (v/v); Bayer, Leverkusen, Germany) combined with nitrous oxide (60% (v/v); 4 L/min) and oxygen (38.5% (v/v); 2 L/min). Ophthalmic eye ointment was applied to the eyes to prevent drying during surgery. The back of the animal was shaved and the surgical site cleaned with 4% (w/v) chlorhexidine solution. Skin overlying the thoracic area and underlying musculature was cut, and excess muscle removed from the dorsal and lateral processes of the vertebrae. A partial laminectomy of the 10 vertebra was performed using Rongeurs (Fine Science Tools (FST), North Vancouver, BC, Canada) to expose the underlying spinal cord without disrupting the dura. Surrounding bone was cleared as needed to provide sufficient clearance for the impactor head to access the dorsal surface of the spinal cord. A moderate (200 kdyn (2 N)) contusive SCI was performed at the T10 level using an Infinite Horizon impactor (Precision Systems and Instrumentation; Lexington, KY, USA).

Following injury, muscles were sutured and the overlying skin was closed with wound clips (Michel Suture Clips; FST). Rehydrating normal saline (2 mL, subcutaneous (SC), 0.9% (w/v) sodium chloride; Baxter, Deerfield, IL, USA) and antibiotic Benacillin (0.02 mL/100 g body weight, 300 U/mL, intramuscular (i.m.; gastrocnemius), 150 mg/mL procaine penicillin, 150 mg/mL benzathine penicillin, 20 mg/mL procaine hydrochloride); Ilium, Troy Laboratories, Glendenning, NSW, Australia) were administered immediately following surgery. Animals were returned to clean cages and placed in a heating cabinet (26°C) for 24-48 hours postsurgery to aide recovery from anaesthesia. Normal saline (0.5-2 mL) and buprenorphine (0.25-1 μg/100 g body weight; dose reduced every second day) were administered (SC) daily for 1 week post-surgery. To prevent bladder infection, antibiotic (Benacillin; 0.02 mL/100 g body weight) was administered (IM; alternating legs) every second day for 1 week post-surgery. Bladders were manually expressed twice daily for 2 weeks or until normal bladder function returned.

Peptide treatment

Custom APP96-110 (active) and mAPP96-110 (mutant; with reduced heparin binding ability (Corrigan et al., 2014)) peptides were produced by Auspep Pty Ltd (Tullamarine, VIC, Australia) according to the sequences; APP96-110: AC-NWCKRGRKQCKTHPH-NH2; mAPP96-110: AC-NWCNQGGKQCKTHPH-NH2). The APP96-110 peptide contained a disulphide bridge between cysteines 98 and 105, important for efficacy (Small et al., 1994; Corrigan et al., 2014). For animals that received peptide treatment (Table 1), a single intravenous injection of active or mutant peptide (0.05 mg/kg) in normal saline (Baxter) was administered via the tail vein at 30 minuntes post-SCI in accordance with previous literature (Plummer et al., 2018).

hMSC culture

Clinical grade hMSCs were obtained from Cell and Tissue Therapies WA (CTTWA; Royal Perth Hospital, Perth, Western Australia, Australia) and had been isolated using methods similar to those described previously (Herrmann et al., 2012; Hodgetts et al., 2013a, b). Frozen hMSCs were rapidly thawed in a 37°C water bath, washed in minimum essential medium-alpha modification (α-MEM; Gibco, Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA) supplemented with 10% (v/v) foetal bovine serum (FBS; Gibco) and seeded into T75 flasks (Corning, St. Louis, MO, USA) at a concentration of 2.5-3.5 × 103cells/cm2in α-MEM/10% FBS. Cells were maintained in α-MEM/10% FBS and incubated at 37°C/5% (v/v) carbon dioxide (CO2) for transplantation, or used forin vitrodifferentiation and characterisation studies.

In vitro differentiation

To confirm multipotencyin vitro, donor hMSCs were differentiated into osteoblasts, adipocytes and chondrocytes using StemXVivo Osteogenic/Adipogenic/Chondrogenic differentiation media (R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN, USA) according to manufacturers’ instructions. Differentiation was confirmed by staining fixed cells on microscope slides with 2% (w/v) Alizarin Red S (Sigma-Aldrich; osteoblasts), 0.3% (w/v) Oil Red O in isopropanol (Sigma-Aldrich; adipocytes), or 0.05% (w/v) Toluidine blue O (Sigma-Aldrich; chondrocytes) followed by solvent (e.g. acetone, xylene) dehydration.

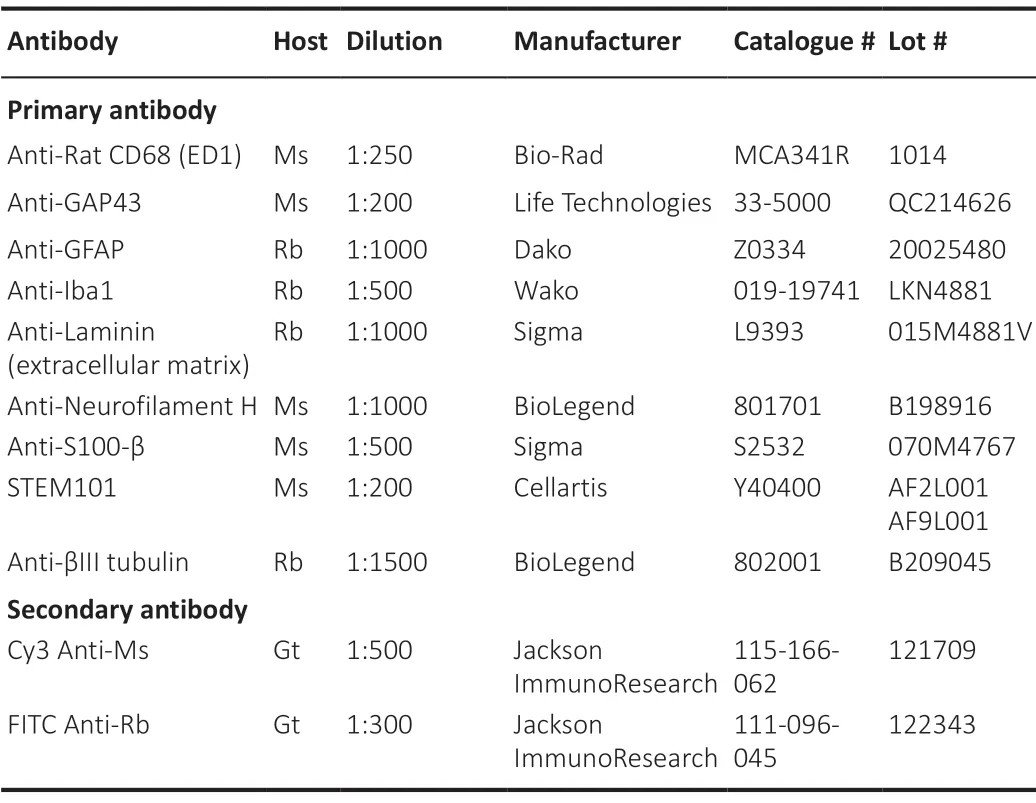

In vitro characterisation

Non-differentiated donor hMSCs were seeded onto 0.1 mg/mL (w/v) poly-L-lysine (PLL; Sigma-Aldrich)/0.05 mg/mL (w/v) laminin (Sigma-Aldrich) coated 8-well chamber slides, at a concentration of 1 × 104cells/well. Cells were grown to 80-90% confluence, fixed in 4% (w/v) paraformaldehyde (PFA; Sigma-Aldrich) and assessed for marker expression against the panel of antibodies outlined inTable 2.

Table 2 |Primary and secondary antibodies used for immunohistochemistry

Preparation for cell transplantation

Donor hMSCs (passage 3-5) for spinal cord transplantation were used directly from culture. Once cells had grown to 80-90% confluence, flasks were washed 3× with Hanks’ balanced salt solution (HBSS; Gibco), incubated with 0.05% Trypsin-EDTA (Gibco) for 3-5 minutes until adherent cells were detached from the flask surface, then cells were collected into fresh α-MEM/10% FBS. The cell suspension was centrifuged, supernatant discarded and the cell pellet resuspended in PBS (Gibco). Cell viability was determined using trypan blue (Sigma-Aldrich) staining, and the cell suspension was adjusted to a concentration of 6.25 × 104viable cells/μL. For non-viable (nv; control) cells (nv-hMSCs), prepared cell suspensions were repeatedly freeze-thawed in liquid nitrogen until the cells were no longer viable as indicated by trypan blue staining (< 5% viability after 4 freeze/thaw cycles). Non-viable hMSCs are an appropriate control to assess whether the effects of cell transplantation on experimental outcomes are due to the ongoing influence of any live engrafted donor cells remaining in the lesion site, in contrast to the simple addition of (inactive) cellular material that could modulate the transplantation site to provide a more favourable terrain for repair, regrowth and/or regeneration (Katoh et al., 2019). All cell suspensions were stored on ice prior to and for the duration of the transplantation surgery (viable cells remain ~90% viable after 6 hours on ice as determined by trypan blue staining).

Cell transplantation

At 1 week post-injury, cohorts of animals received transplantation of either viable or non-viable (nv) hMSCs into the spinal cord lesion site (Table 1; 5 × 105cells in 8 μL PBS total). Animals were prepared for cell transplantation surgery and anaesthetised as described previously. The incision site along the dorsal surface of the skin and the underlying musculature were reopened, and clamps from the IH impactor apparatus were attached to vertebra adjacent to the injury site (~T8 and T12) in order to immobilise the spinal column of the animal. Any scar tissue overlying the spinal cord was removed using fine forceps (Dumont #5 forceps; FST) and the dura carefully opened using a fine needle tip (26G; Terumo, Shibuya, Tokyo, Japan) without disturbing the spinal cord. Glass micropipettes (60 μm tip diameter; Blaubrand, Wertheim, Baden-Württemberg, Germany) for cell injection were pulled using a P-2000 Laser-Based Micropipette Puller (Sutter Instruments, Novato, CA, USA) with the following settings; heat = 750, filament = 5, velocity = 30, delay = 200, pull = 50. Fine forceps (FST) were used to modify the pipette tip to the appropriate diameter. The micropipette was attached to a 10 μL Hamilton syringe (Hamilton, Reno, NV, USA) with polyethylene tubing (Becton Dickinson, Franklin Lakes, NJ, USA) and positioned using a stereotaxic frame (Kopf Instruments; Tujunga, CA, USA). Two injections of 2.5 × 105donor hMSCs/nv-hMSCs in 4 μL PBS (5 × 105cells in 8 μL total) were delivered into the contusion site (rostral and caudal to the lesion epicentre, at the midline of the spinal cord) at a depth of 1 mm. Donor cells were delivered at a rate of 0.5 μL/min for 8 minutes using a syringe pump (Harvard Apparatus, Holliston, MA, USA). The micropipette was left in place for 1 minute following delivery to minimize efflux of cells after pipette withdrawal. Following transplantation, muscles were again sutured and overlying skin closed with wound clips. Animals were returned to clean cages and placed in a heating cabinet (26°C) for 24 hours to aid recovery following surgery. Rehydrating normal saline, analgesic and antibiotic were administered for 1 week post-surgery, as described above (Hodgetts et al., 2013a, b, 2018).

Functional analyses

Functional recovery assessment in spinal cord injury studies require multiple tests in order to indicate robust outcomes. Whilst it is not always possible to link functional outputs directly to any morphological improvements or changes, a range of different functional outputs were used to assess; hindlimb (HL) recovery specifically in open field and on a horizontal ladder (as a general indicator of recovery of function with time). Additionally our own RatWalk gait analysis was used to reveal any potential changes in patterns of forelimb/hindlimb (FL/HL) coordination. HL function was assessed weekly using open field locomotor (BBB) scoring (Basso et al., 1995), LadderWalk, and RatWalk analyses.

Open field locomotor analysis

Hindlimb (HL) function was assessed weekly from day 7 post-SCI using the 21-point Basso, Beattie, Bresnahan (BBB) locomotor rating scale (Basso et al., 1995). Rats were allowed to freely move about an open field for 3-4 minutes while observers scored the degree of HL function demonstrated. At least two observers independently scored each animal and all observers were blinded to the treatment group. All BBB runs were video recorded for further analysis by additional observers (if needed). Individual scores were assigned for the right (R) and left (L) HL, and the highest recorded score was used for analysis (most scores differed by ≤ 2 points). BBB scores for each treatment at each time point were averaged and are presented as non-rounded values. Rats that attained a BBB score of 10, representing occasional (≤ 50%) weight supported plantar steps, were subjected to further behavioural testing on LadderWalk and RatWalk platforms.

LadderWalk analysis

Rats were video recorded while completing 3 passes of a 1 m long horizontal ladder with varying distances between the ladder rungs (Soblosky et al., 1997; Metz and Whishaw, 2002; Webb and Muir, 2003; Hodgetts et al., 2018). The number of right (R) and left (L) HL missteps were noted individually, where a misstep was defined as an incorrect paw placement that results in the foot falling below the ladder rungs and/or the loss of controlled HL weight support. The total number of missteps (R + L HL missteps) were averaged over the 3 passes for each animal and used to calculate the average number of missteps for each treatment group at each time point.

RatWalk analysis

Rats completed 3 passes across a 1-m long horizontal glass platform while their paw prints were video recorded from below. The paw prints were later identified and assigned as right or left (R/L) and fore- or hind-limb (FL/HL), in step sequence, using the RatWalk computer program designed independently in our laboratory (Godinho et al., 2013; Hodgetts et al., 2018), based on the CatWalk program (Hamers et al., 2001, 2006). RatWalk generates data that reflects locomotor characteristics such as step sequence, coordination pattern, stride length and stance width (Godinho et al., 2013; Hodgetts et al., 2018). The results generated were averaged over the 3 passes for each animal, then averaged for each treatment group at each time point.

Tissue processing and morphological analysis

Eight weeks after SCI, animals were euthanased with a lethal injection (IP) of sodium pentobarbitone (lethabarb; Virbac, Carros, France). A heart bleed was performed immediately before transcardial perfusion with 150 mL of heparinised PBS (1% (v/v) heparin, Hospira, Lake Forest, IL, USA) and fixation with 150 mL of 4% (w/v) PFA. The vertebral column was removed and post-fixed (4% (w/v) PFA) for at least 24 hours at 4°C before the spinal cord was dissected out and stored in 4% (w/v) PFA at 4°C.

A 1 cm segment of spinal cord, with the injury site at the midpoint of the segment, was removed for sectioning. Spinal cord segments were cryoprotected in 30% (w/v) sucrose in PBS overnight (O/N) at 4°C, then embedded in 10% (w/v) gelatin (DifcoTM; Becton Dickinson) in PBS. Blocks were fixed in 4% (w/v) PFA for 2 hours at RT, cryoprotected in 30% (w/v) sucrose O/N at 4°C, then frozen O/N at -20°C. Spinal cord blocks were sectioned using a CM3050 Leica cryostat (temperature maintained at -22°C to -20°C; Leica Biosystems, Nussloch, Baden-Württemberg, Germany) and serial 40 μm thick longitudinal sections were transferred in sequence to 24-well plates containing 0.2% (v/v) sodium azide (Sigma-Aldrich) in PBS. All sections were stored at 4°C until used for histological staining and immunohistochemistry.

Toluidine blue staining and cyst analysis

To analyze cyst formation within the lesion site, every sixth spinal cord section was mounted onto subbed slides (2% (w/v) gelatin, 0.2% (w/v) chromium (III) potassium sulphate (Sigma-Aldrich) in dH2O) and allowed to air-dry O/N. Slides were submerged in toluidine blue solution (0.05% (w/v) Toluidine blue O (Sigma-Aldrich) and 0.005% (w/v) sodium tetraborate (Sigma-Aldrich) for 30-40 seconds, immediately rinsed in dH2O and dehydrated in graded alcohols (70, 90 and 100% (v/v)) for 3 minutes each. Slides were air-dried O/N then coverslipped with Leica CV Mount (Leica Biosystems).

Toluidine blue stained slides were scanned at 20X magnification using a Leica Aperio ScanScope XT digital slide scanner (Leica Biosystems), and the resulting data files were processed using Aperio ImageScope software (Leica Biosystems). Image-Pro Plus software (version 6.2; Media Cybernetics, Rockfield, MD, USA) was used to outline the borders of each section and all cysts, in order to calculate the total tissue and cyst areas. The cyst areas for each section were summed and used to calculate the total cyst area as a percentage of the total section area. The percentage cyst for each section was averaged across all sections analyzed to give the average percentage cyst per animal, which was then averaged for each treatment group (Hodgetts et al., 2013a, b, 2018).

Immunohistochemistry and fluorescence quantitation

The fluorescence intensity of neuronal [βIII tubulin, growth associated protein-43 (GAP43), SMI32], glial [S100, glial fibrillary acidic protein (GFAP)], extracellular matrix (ECM; laminin) and immune cell (Iba1, ED1) markers was analyzed on three sections (each 240-320 μm apart) per antibody, surrounding the midline of the spinal cord. Free-floating sections were blocked in 10% (v/v) FBS and 0.02% (v/v) Triton-X 100 in PBS for 30 minutes at RT. Sections were washed 3 times over 5 minutes in PBS and incubated with primary antibodies (Table 2) diluted in PBS O/N at 4°C in a humidified chamber. Primary antibodies were removed, sections were washed 3 times over 5 minutes in PBS and incubated with secondary antibodies (Table 2) diluted in PBS for 30 minutes at RT, protected from light. Secondary antibodies were then removed and sections washed 3 times over 5 minutes in PBS, mounted onto slides (Menzel-Gläser, ThermoFisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA) and allowed to air-dry (1-2 hours) before being coverslipped with ProLong® Diamond Antifade Mountant (Molecular Probes, Eugene, OR, USA) and air-dried O/N, protected from light. All slides were stored at 4°C and protected from light until imaged.

Tiled fluorescent images were taken at 20× magnification using a Photometrics CoolSNAP EZ camera (Teledyne Photometrics, Tucson, AZ, USA) attached to a Nikon Eclipse Ti microscope (Coherent Scientific, Australia) with NISElements BasicResearch software (Melville, NY, USA). For analysis of fluorescence intensity (used as an indicator of the amount of protein expression), the images for each antigen were taken using the same exposure time, gain and camera settings. Sections were not exposed to light prior to imaging and all sections stained with a particular antibody, for each experiment, were imaged on the same platform during the same imaging session. Images were analyzed with NIS-Elements BasicResearch software to determine the fluorescence intensity of whole images. The threshold for fluorescence intensity was set/determined using secondary only (negative/secondary control) stained sections to assign background fluorescence. Pixels above background were counted as positive and the amount of positive fluorescence per field of view was recorded. The minimum, maximum, average and sum intensity were recorded and averaged across the 3 images for each animal, then averaged for each treatment group.

Detection and quantification of human nuclei

Human MPC survival was confirmed with human nuclear antigen (HNA) STEM101 antibody to detect human nuclei in Nude rat spinal cord sections. Thein vivopresence of donor hMSCs and possible interactions between the cell graft and host tissue were assessed with double labelling of STEM101 with various markers, and also by immunostaining sections adjacent to those containing STEM101 positive cells. Three sections per animal were double stained to compare the distribution of STEM101+cells with βIII tubulin (neuronal), GFAP (glial), and laminin (ECM) immunoreactivity. Sections analyzed were selected based on the results of toluidine blue staining. For identification of human nuclei (hMSCs), tiled confocal images were taken at 20× magnification on a Nikon A1 Confocal Microscope (Nikon) (Coherent Scientific, Australia) with NIS-Elements AdvancedResearch software (version 4.13; Nikon, Melville, NY, USA). Images were taken at 1.5 μm z-step intervals through the tissue, and the resulting image at each step was analyzed for antigen co-localisation. Maximum intensity projection images were created from z-stacks using NIS-Elements AdvancedResearch software. Due to limitations on the location of sections (within the spinal cord and relative to the cell transplant location) and the number of sections available for STEM101 immunohistochemistry, one section per animal was used for human nuclei counts. The section that appeared to have the largest number of STEM101+nuclei was analyzed. STEM101+human nuclei were manually counted using Image-Pro Plus software (Media Cybernetics, Rockville, MD, USA) and the average number of human nuclei calculated for each treatment group.

Statistical analysis

Statistical tests were conducted using GraphPad Prism (version 7.01; GraphPad, San Diego, CA, USA) and/or GenStat (18thEdition; VSN International Ltd., Hemel Hempsted, Hertfordshire, UK). Statistical analysis of BBB scoring was carried out using the Kruskal-Wallis test (non-parametric analysis of variance (ANOVA)) with Bonferroni correction for multiple comparisons. One- or two-way ANOVA with Fisher’s least significant difference (LSD; at 5%) were used for all other analyses to assess differences between pre-injury animals and each treatment group (one-way), and differences between treatment groups (two-way). We considered statistical significance atP< 0.05. Quantitative analysis of donor hMSC survival at 7 weeks post-transplantation (Table 3) was performed using a two-samplet-test.

Table 3 |Quantitative analysis of donor hMSC survival at 7 weeks posttransplantation

Results

Functional recovery

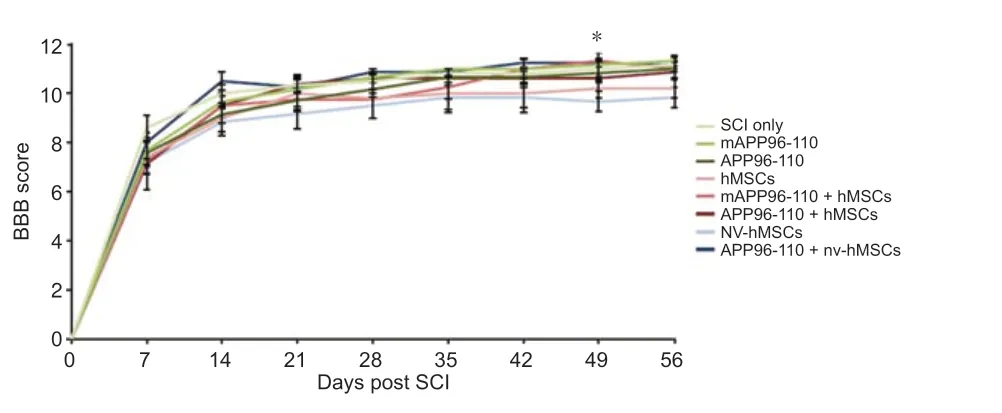

After the complete loss of HL function immediately following SCI (D0) there was a gradual recovery of function over the 8 week experimental period (Figure 1). However, while the nv-hMSC group consistently showed the lowest BBB scores, statistical analysis did not reveal any significant differences in the functional recovery between SCI only and any treatment group, nor between groups, for any functional test up to D56. No group recovered to pre-injury scores. There was a significant increase in BBB score with APP96-110 + nv-hMSCs compared to nv-hMSCs at D49 (P< 0.05;Figure 1), however this was not maintained for the following (final) week. By D56, all groups demonstrated occasional to frequent weightsupported plantar stepping (BBB 10 to 11) with no significant differences in the average BBB score between any groups at D56 (Figure 1;P> 0.05).

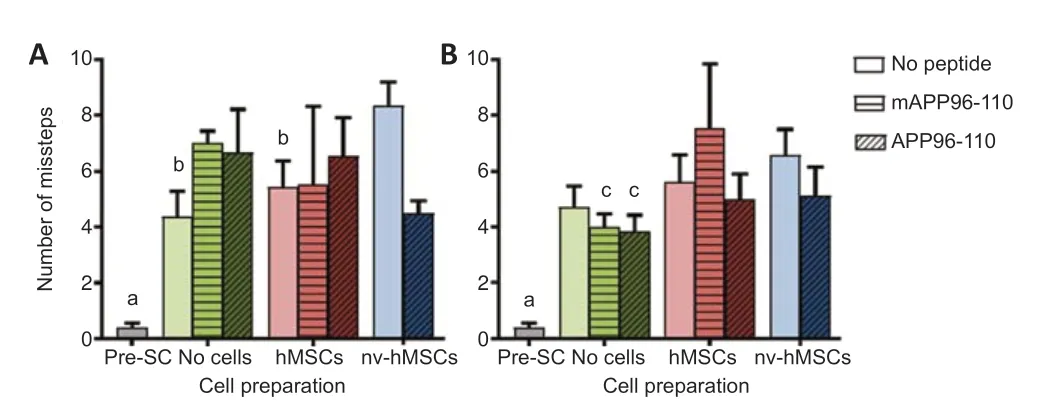

LadderWalk analysis showed a significant impact of SCI on HL function (Figure 2), as seen by a significant increase in the number of missteps at D35 (A) and D56 (B) post-SCI compared to pre-injury scores (P< 0.05). While no group recovered to pre-injury scores, there were significantly fewer missteps at D35 for SCI only, hMSCs and APP96-110 + nv-hMSCs compared to nv-hMSCs (P< 0.05), and at D56 for mAPP96-110 and APP96-110 compared to mAPP96-110 + hMSCs (P< 0.05).

RatWalk analysis was used to assess aspects of functional recovery such as stance width, stride length and the frequency of different coordinating patterns for animals that had attained a BBB score of 10, demonstrating occasional weightsupported plantar stepping. SCI significantly reduced forelimb (FL) and HL stance widths and stride lengths at D35 and D56 compared to pre-injury (P< 0.05, one-way ANOVA). FL stance width and stride lengths were 42-50% shorter, and HL stance width and stride lengths were 18-28% shorter post-injury compared to pre-injury. There were largely no differences in stance width or stride length between treatments; however at D56, HL stride lengths were larger (~20%) for SCI only, APP96-110 and nv-hMSCs compared to hMSCs (data not shown;P< 0.05, two-way ANOVA significance for HL). Importantly, there were no progressive differences in stance width or stride length for each treatment between D35 and D56, indicating no consistent change or improvement with time. With regard to coordinating patterns of limb movement, there were no significant differences in the amount of each coordinating pattern demonstrated pre-injury compared to D35 and D56 post-SCI (data not shown). This is possibly due to the large variation in the amounts of each coordinating pattern demonstrated by individual animals during triplicate RatWalk passes (pre- and post-injury), and the likelihood that animals will use some coordinating pattern to locomote (once weight supported stepping has returned) regardless of injury severity or amount of HL functional control.

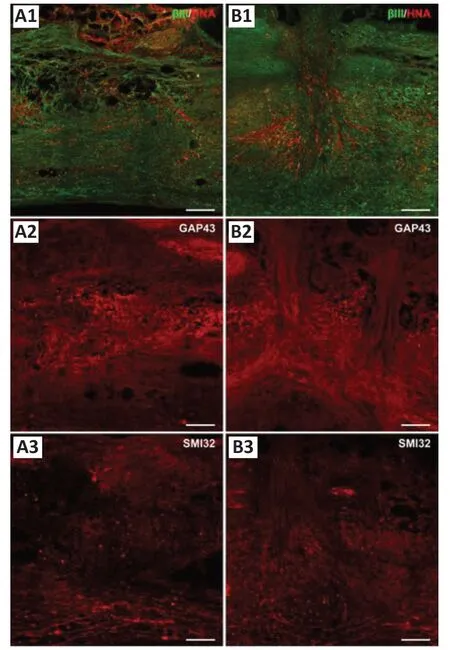

Morphological and immunohistochemical analyses APP96-110 peptide combined with MSC transplants

Areas with grafted hMSCs appeared in toluidine blue stained sections as dark blue stained, dense, fibrous areas that had a particular alignment within the tissue (extending rostral/caudal from the injection site or dorsal/ventral along the transplantation needle track - data not shown). Neuronal marker profiling identified a clear injury site that was void of organized neuronal tissue, lacked distinguishable grey and white matter regions and was bordered rostrally and caudally by uninjured tissue, and ventrally by spared tissue. In some cases, the injury site extended up to 6 mm in length (rostral/caudal). The number of βIII tubulin+, GAP43+and SMI32+fibers varied greatly between groups and appeared to be denser and more numerous in hMSC treated animals. The majority of neuronal fibers extending within the lesion site lacked specific orientation and organization, however many fibers were orientated with the hMSC graft in hMSC treated animals. At D56 (49 days post-transplantation) numerous βIII tubulin+axons filled the lesion site and were closely associated with STEM101+hMSCs (Figure 3A1andB1). Similarly, numerous GAP43+(Figure 3A2andB2) and SMI32+(Figure 3A3andB3) fibers surrounded and extended through hMSC graft areas. Neuronal fibers appeared to be denser and more aligned when associated with hMSC graft areas, perhaps indicating that the grafted cells promoted and/or supported the regrowth/regeneration of neuronal processes.

STEM101 distinguishes uniformly sized, oval human nuclei from surrounding autofluorescent macrophages (intense,varied autofluorescence and a foamy/spongy morphology with uneven borders). Human MSCs often migrated 1-3 mm (rostral/caudal) within the lesion site itself and in some cases extended dorsal/ventral within the needle track (data not shown). Viable STEM101+donor hMSCs survived to at least 7 weeks after transplantation (Table 3). However, even at 7 weeks post-transplantation there was no evidence of migration of viable hMSCs into adjacent intact host tissue. There was a significant increase in the average number of STEM101+nuclei with viable hMSCs (hMSCs only and APP96-110 + hMSCs) compared to nv-hMSCs (nv-hMSCs only and APP96-110 + nv-hMSCs;P< 0.05). There was also a significant increase in the average number of STEM101+nuclei with hMSCs compared to APP96-110 + hMSCs (P< 0.05), however neither group was significantly different to mAPP96-110 + hMSCs (P> 0.05), due to the large variance in STEM101+human nuclei counts of mAPP96-110 + hMSCs animals.

Astrocytes (S100+or GFAP+) were evenly distributed throughout uninjured tissue and present within the lesion site to varying degrees. The lesion site was largely devoid of S100 and GFAP immunoreactivity, particularly in cell transplanted animals. GFAP immunoreactivity was strongest in tissue immediately adjacent to the injury site and/or hMSC graft regions. There was limited interaction between donor hMSCs and host glial cells, identified by GFAP (astrocytes) or S100 (astrocytes and perhaps infiltrating Schwann cells) immunoreactivity. As shown inFigure 4A1andB1, there was intense GFAP immunoreactivity at the border between host tissue and the hMSC graft with very few GFAP+processed extending into the graft. S100 immunoreactivity followed a similar pattern with abundant S100+profiles surrounding the graft and few S100+process extending into the graft area (not shown).

Laminin deposits filled and bridged the lesion site of all animals, extending between uninjured rostral and caudal tissue. Extensive tubular laminin deposits filled the lesion site of all hMSC transplanted animals and appeared to be greatest in areas within and immediately surrounding the hMSC graft (not quantified;Figure 4A2andB2). Accordingly, laminin+profiles were often orientated with the direction of the hMSC graft.

Iba1+and ED1+microglia/macrophages were present within the lesion site and in surrounding uninjured tissue of all animals at 8 weeks post-SCI. Iba1 and ED1 immunoreactivity identified resident and infiltrating microglia/macrophages within the injury site that had either an amoeboid morphology with short processes characteristic of activated microglia or a large, foamy/spongy morphology characteristic of phagocytotic microglia/macrophages (ED1+,Figure 4A3andB3). Iba1+cells present within the injury site often aligned with the hMSC graft while ED1+cells were often concentrated at the border of the graft with few ED1+cells infiltrating the graft area. ED1 immunoreactivity appeared weaker within graft areas than the surrounding tissue, suggesting that donor hMSCs may be influencing the activation and infiltration of microglia/macrophages to varying degrees.

Every sixth spinal cord section was toluidine blue stained to visualise tissue morphology and cyst formation. Cyst formation occurred in all animals following SCI. Large cysts were visible within the lesion epicentre of SCI only and APP96-110 treated animals, and in some cases, some cyst formation occurred in tissue rostral and caudal to the lesion site. In contrast, in animals that also received cell grafts, spared/sprouting/regrowing tissue and extracellular matrix (ECM) deposits were present within the lesion epicentre, with numerous smaller cysts surrounding the lesion site, and in tissue rostral and caudal to the lesion site (data not shown). After quantifying these cyst sizes, it was revealed that treatment with mAPP96-110 significantly reduced cyst size (Figure 5) compared to SCI only (P< 0.05), while combined treatment with mAPP96-110 + hMSCs, APP96-110 + hMSCs and APP96-110 + nv-hMSCs significantly reduced cyst size compared to SCI only and APP96-110 (P< 0.05). APP96-110 + hMSCs also significantly reduced cyst size compared to nv-hMSCs (P< 0.05).

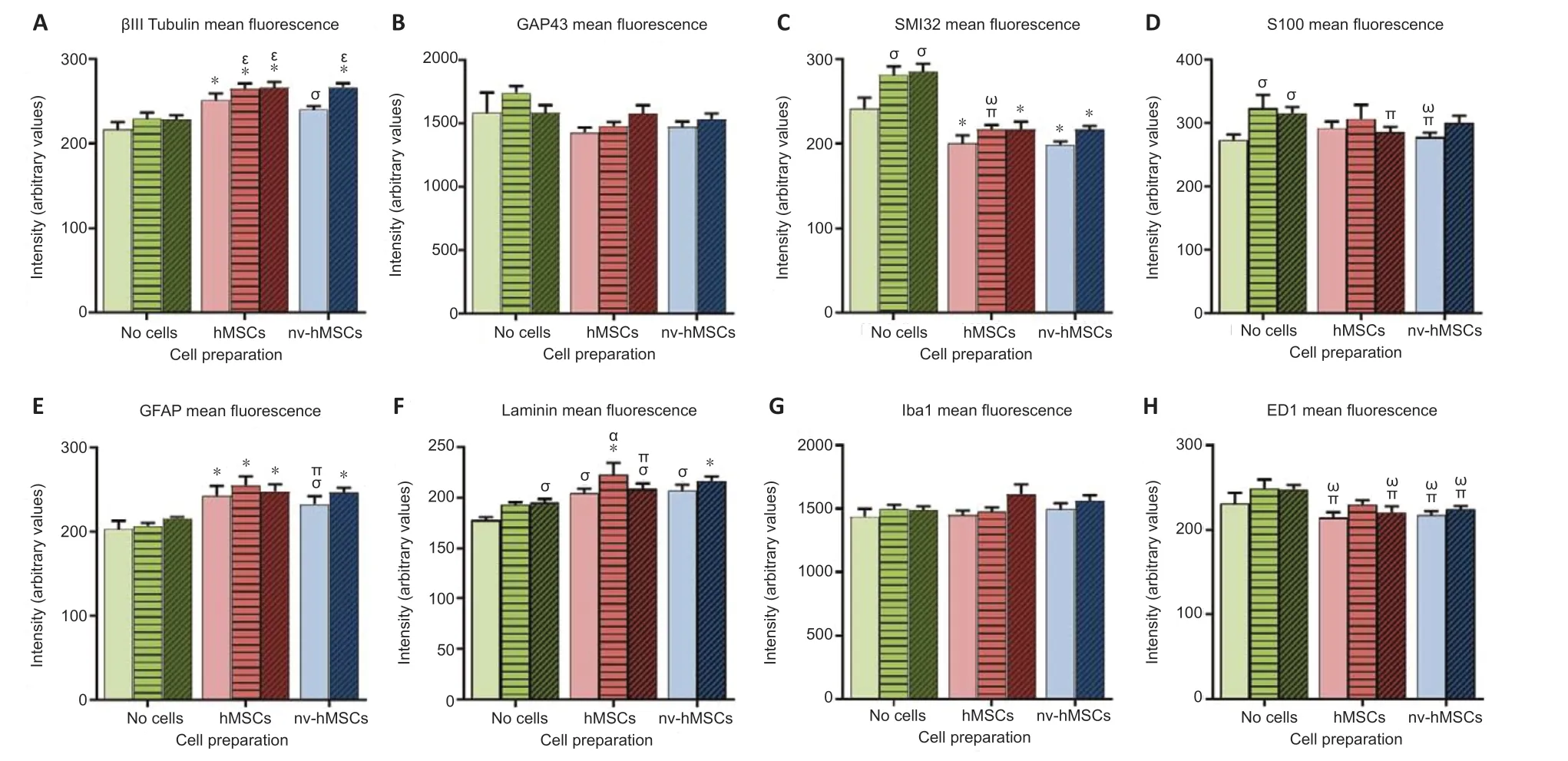

Quantification of immunostaining Neuronal markers

There was a significant increase in the average fluorescence intensity of βIII tubulin with hMSCs, mAPP96-110 + hMSCs, APP96-110 + hMSCs and APP96-110 + nv-hMSCs compared to SCI only, mAPP96-110 and APP96-110 and nv-hMSCs (P< 0.05, two-way ANOVA). There was also a significant increase with nv-hMSCs compared to SCI only (Figure 6A). Conversely, there was a significant decrease in the average fluorescence intensity of SMI32 with hMSCs, APP96-110 + hMSCs, nvhMSCs and APP96-110 + nv-hMSCs compared to SCI only, mAPP96-110 and APP96-110, and mAPP96-110 + hMSCs compared to mAPP96-110 and APP96-110, and a significant increase in SMI32 fluorescence intensity with mAPP96-110 and APP96-110 compared to all other groups (no difference between mAPP96-110 and APP96-110) (P< 0.05, two-way ANOVA) (Figure 6C). There was no difference in the average fluorescence intensity of GAP43 between any groups (P> 0.05, two-way ANOVA) (Figure 6B).

Glial markers

There was a significant decrease in the average fluorescence intensity of S100 with APP96-110 + hMSCs and nv-hMSCs compared to mAPP96-110 and/or APP96-110 (P< 0.05, two-way ANOVA). Whereas mAPP96-110 and APP96-110 significantly increased S100 fluorescence intensity compared to SCI only (Figure 6D). There was a significant increase in the average fluorescence intensity of GFAP with hMSCs, mAPP96-110 + hMSCs, APP96-110 + hMSCs and APP96-110 + nvhMSCs compared to SCI only, mAPP96-110 and APP96-110, and with nv-hMSCs compared to SCI only and mAPP96-110 (P< 0.05, two-way ANOVA) (Figure 6E).

Laminin

There was a significant increase in the average fluorescence intensity of laminin with APP96-110, hMSCs, APP96-110 + hMSCs and nv-hMSCs compared to SCI only and/or mAPP96-110, and mAPP96-110 + hMSCs and APP96-110 + nv-hMSCs compared to SCI only, mAPP96-110 and APP96-110, and/or hMSCs (P< 0.05, two-way ANOVA) (Figure 6F).

Microglia/macrophage markers

There was no difference in the average fluorescence intensity of Iba1 between any groups (P> 0.05, two-way ANOVA) (Figure 6G), however there was a significant decrease in the fluorescence intensity of ED1 with hMSCs, APP96-110 + hMSCs, nv-hMSCs and APP96-110 + nv-hMSCs compared to mAPP96-110 and APP96-110 (P< 0.05, two-way ANOVA) (Figure 6H).

Figure 1|Open field locomotor recovery as assessed with BBB scoring.

Figure 2|Hindlimb functional recovery as assessed by LadderWalk.

Figure 3|Immunostaining of adjacent longitudinal sections of the same injured spinal cord grafted with donor hMSCs, examined at D56 (49 days post-transplantation) revealing neuronal marker (βIII tubulin+, GAP43+ and SMI32+ fiber) profiles in injury sites.

Figure 4|Immunostaining of adjacent longitudinal sections of the same injured spinal cord grafted with donor hMSCs examined at D56 (49 days post-transplantation) revealing astrocytic (GFAP+), extracellular matrix (laminin+) and microglial/macrophage (ED1+) marker profiles in injury sites.

Figure 6|Mean fluorescence intensities of various immunostained sections.

Discussion

Based on recent studies reporting neuroprotective effects of APP96-110 following TBI (Corrigan et al., 2014; Plummer et al., 2016, 2018), we investigated the neuroprotective potential of the APP96-110 peptide following SCI. In summary, while occasional functional improvements were seen, they were inconsistent between groups and across BBB, LadderWalk and Ratwalk tests, thus their biological significance is unconvincing. Nonetheless, there were some improvements in outcomes using morphological measures. Surprisingly, and for reasons that remain unclear, the mutant APP96-110 peptide, but not APP96-110, significantly reduced cyst size compared to SCI. Importantly however, both peptides significantly reduced cyst size when combined with viable hMSCs, an effect that was not seen with hMSC transplantation alone. In our previous studies treatment with human mesenchymal precursor cells after SCI resulted in reduced cyst size (Hodgetts et al., 2013a, b), which may highlight the possibility of specific donor variation within these human mesenchymal isolates. Fluorescence intensity was used as an indicator of the amount of protein expression for each antigen in spinal cord sections. Treatments with viable and nv hMSC transplantation (± APP96-110) significantly increased βIII tubulin, GFAP and laminin, and decreased SMI32, S100 and ED1 fluorescence intensity, whereas mAPP96-110 and APP96-110 alone significantly increased SMI32 and S100 fluorescence intensity. Donor hMSC survival was significantly higher with hMSCs compared to APP96-110 + hMSCs, however neither group differed when compared to mAPP96-110 + hMSCs.

Importantly, the same peptides and essentially identical protocols/doses used in the previous brain studies (Corrigan et al., 2014; Plummer et al., 2016, 2018) were used in our SCI model, and yet resulted in different outcomes from a functional perspective. We consider below how the potential factors defining the efficacy of a particular therapeutic approach in one CNS injury model may not necessarily be observed in other neurotrauma models.

Administered alone, APP96-110 peptide did not produce any consistent improvements in either functional or morphological outcomes post-SCI. While the effectiveness of a therapeutic approach in a particular CNS injury model often provides the justification for investigation in other models, it does not guarantee that similar outcomes will occur. It seems likely that the neuroprotective effects of APP96-110 following TBI reported previously by Corrigan et al. (2014) and Plummer et al. (2018) were not replicated in this study due to differences in the animal and CNS injury models used. Not only are there significant differences in the inflammatory response (and injury development in SCI) between mice and rats (Sroga et al., 2003), but also between different strains of the same species (Popovich et al., 1997; Kigerl et al., 2006), and between animals of different ages (Kumamaru et al., 2012; Sutherland et al., 2016). Although both are part of the CNS, the brain and spinal cord exhibit significantly different inflammatory immune responses [reviewed by Zhang and Gensel (2014)]. Overall, the timing and duration, and magnitude of the inflammatory immune response to injury is greater in the spinal cord than the brain, with significantly greater microglia/macrophage and astrocyte activation, and neutrophil and lymphocyte infiltration following SCI than TBI (Schnell et al., 1999; Batchelor et al., 2008). Injury severity also significantly affects the magnitude of the inflammatory response with the amounts of blood-spinal cord barrier (BSCB) and inflammatory tissue damage, and secondary degeneration directly related to the force of the primary mechanical injury (Noble and Wrathall, 1989a, b; Yang et al., 2005; Maikos and Shreiber, 2007). Consequently, some pharmacological and cell-based therapies that are efficacious in mild SCI are less effective in moderate or severe injury models [e.g. cell transplantation (Himes et al., 2006; Zheng et al., 2011; Yokota et al., 2015)]. Clearly then, potential neuroprotective therapies for CNS trauma need to be tailored to suit the injury model and injury severity accordingly.

The dose and route of administration can also affect the efficacy of pharmacological therapies. Increasing the concentration of APP96-110 significantly improves neuroprotective effects following TBI, possibly due to increased heparin binding (from more peptide being available) leading to increased downstream effects that contribute to greater neuroprotection. Because of this, and the differences in the inflammatory immune responses between TBI and SCI discussed previously, future studies should investigate the effects of increased APP96-110 concentrations following SCI, in order to determine whether APP96-110 can have neuroprotective effects following SCI, and whether these effects are dose dependent. Both intravenous and intracerebroventricular APP96-110 injections have been tested following TBI (Corrigan et al., 2014; Plummer et al., 2018). The latter approach bypasses the blood-brain barrier and delivers the peptide directly to the brain. Although intravenous injection may be less invasive and a more clinically relevant method of delivery than intraspinal injection, it relies on the peptide being able to cross the compromised BSCB or the peptide having systemic effects within the body. Although BSCB permeability is increased for a number of weeks following mechanical injury (Popovich et al., 1996), the overall permeability, and permeability to proteins of different molecular weights varies greatly with injury severity (Noble and Wrathall, 1989a, b; Maikos and Shreiber, 2007). It may be that direct injection into the spinal cord via intralesional or intrathecal injection (single administration), or implantation of a mini-osmotic pump (continuous administration) at the lesion site bypasses the BSCB and provides a more effective route of administration. The incorporation/fusion of neuroprotective peptides with nanoparticles, magnetic particles or other cell penetrating peptides (e.g. TAT) that can cross the BSCB may also improve peptide delivery to the spinal cord (Hwang and Kim, 2014; Busquets et al., 2015; McGowan et al., 2015; Funnell et al., 2019; Naqvi et al., 2020).

APP96-110 has been suggested to act via heparin binding due to its homology with the D1 heparin binding domain of APP (Corrigan et al., 2011, 2014), and the role of heparin sulphate proteoglycans (HSPGs) in neuronal development, synaptogenesis, cell survival, proliferation and neurite outgrowth (Cui et al., 2013; Swarup et al., 2013; Beller and Snow, 2014). Alternatively, HSPG-mediated peptide endocytosis may produce neuroprotective effects by modulating ion channels and cell surface receptors expressed on neurons (Amand et al., 2012; Meloni et al., 2015a, b). Poly-arginine/arginine-rich peptides exert neuroprotective effects on neuronsin vitroby reducing calcium influx and subsequent calcium-mediated excitotoxicity, however these neuroprotective effects are inhibited if neuronal cultures are treated with heparin prior to peptide administration (Meloni et al., 2015b). Calcium influx inhibition is influenced by peptide cationic charge and arginine content (Meloni et al., 2015a, 2017). Despite being considered as neuroprotective, the modest inhibitory action of COG1410 and APP96-110 peptides in reducing excitotoxic neuronal calcium influx could be due to their relatively low cationic charge and the presence of only two arginine residues, compared to cationic argininerich peptides such as R18 (Chiu et al., 2017). Indeed, a recent study demonstrated that the cationic arginine-rich peptide R18 is more effective than either COG1410 or APP96-110 at reducing neuronal death and calcium influx followingin vitroexcitotoxicity, and that R18 showed greater efficacy than APP96-110 in reducing axonal injury and improving some functional outcomes after TBI (Chiu et al., 2017).

Treatment with arginine-rich peptides also significantly reduces expression of the N-methyl-D-aspartate (NMDA) receptor subunit NR2B (MacDougall et al., 2017) and it is hypothesised that HSPG-mediated peptide endocytosis (initiated by poly-arginine/arginine-rich peptide binding to HSPGs) also leads to the endocytosis of cell surface receptors that may be key mediators of neuronal excitotoxicity (Meloni et al., 2015b; MacDougall et al., 2017). Because APP96-110 is a short peptide (15 amino acids) with two arginine residues, it is considered to be an arginine-rich peptide and some of its neuroprotective effects may be mediated via HSPG-mediated endocytosis. It has been reported that the neuroprotective potential of APP96-110 in the brain is reduced when the APP96-110 peptide is modified to have reduced heparin binding ability (“mAPP96-110” in the present study) (Corrigan et al., 2014), and is increased (to a certain extent) with increased heparin binding ability (Plummer et al., 2016). We used the same heparin-binding peptides, shown to remain stable in the brain for at least 5 hours post injection (Van Den Heuvel, unpublished observations), in our SCI model. Interestingly, our new data showing a reduction in cyst size with the mutant APP96-110 peptide but not APP96-110 treatment suggests that heparin binding ability and HSPGmediated neuroprotection may not completely account for our observations in the spinal cord after trauma.

APP96-110 is also likely to interact with the amyloid precursor-like protein 2 (APLP2), which is homologous with APP, expressed ubiquitously throughout the body (Aydin et al., 2012) and has roles in neuronal development, synaptogenesis, and synaptic plasticity and transmission (Wang et al., 2005; Weyer et al., 2011; Shariati et al., 2013). Like APP, APLP2 expression in the brain significantly increases following TBI (possibly accounting for the neuroprotective effects of APP96-110), however there are no reports on its expression in the spinal cord before or after injury. As APLP2 may be involved in mediating the neuroprotective effects of APP96-110, it is pertinent to determine APLP2 expression in uninjuredvs.injured spinal cords. This study aimed to investigate the potential effects of APP96-110 on donor hMSC survival following transplantation, and whether reduced secondary degeneration (via neuroprotection) promotes a less inflammatory injury site environment that is more conducive to donor cell survival. On the contrary, the number of human nuclei present within the spinal cord at 7 weeks post-transplantation was significantly lower with APP96-110 + hMSCs compared to hMSCs only, however neither of these groups differed from mAPP96-110 + hMSCs. Due to the need for multiple immunohistochemistry runs only a limited number of sections were specifically available for analysis of hMSC survival; further studies will be therefore be needed to confirm these initial observations.

In summary, in contrast to previous neurotrauma studies in the brain, intravenous delivery of APP96-110 at the time of SCI did not produce comprehensive neuroprotective effects (Corrigan et al., 2014; Plummer et al., 2018); this may be associated with differences in the magnitude and development of inflammatory immune responses in TBI versus SCI (Schnell et al., 1999; Batchelor et al., 2008; Zhang and Gensel, 2014). Future studies investigating the effects of increased APP96-110 concentration, alternative routes of delivery, and increased heparin binding ability of APP96-110, may determine whether APP96-110 can indeed exert similar neuroprotective effects following SCI, and whether these neuroprotective effects can be enhanced. In a recent TBI study, animals treated with 0.05 or 0.5 mg/kg APP96-110 after 0.5 hours demonstrated significant improvements in motor outcome, with reduced axonal injury and neuroinflammation at 3 days post-TBI, whereas 5 μg/kg APP96-110 had no effect. In contrast, treatment with 5 μg/kg or 0.5 mg/kg APP96-110 at 5 hours post-TBI demonstrated significant improvements in motor outcome over 3 days, and a reduction in axonal injury (Plummer et al., 2018). Additional dose response and clinically relevant therapeutic time window studies are required to further evaluate the potential of the APP96-110 analogue as a neuroprotective therapy for SCI, and this is a current avenue of investigation. Even though we occasionally obtained beneficial events using the mutant APP96-110, it is hypothesised that active APP96-110 exerts its effects via heparin binding, and potentially the modification of cell surface ion channels and receptors thereby preventing neuronal excitotoxicity (Meloni et al., 2015b; MacDougall et al., 2017). Combining this approach with other neuroprotective therapies or approaches aimed at promoting spinal cord repair (e.g. cell transplantation, scaffolds, growth/trophic factors) may significantly enhance the effects of individual therapies and lead to greater functional and morphological improvements following injury.

Author contributions:Experimental design, performed and provided training in surgical procedures, animal recovery and monitoring, behavioural assays, analysis of results, and primary author manuscript preparation: SIH. Performed surgical procedures, animal recovery and monitoring, behavioural assays, tissue processing: SJL, DBH, AF. Isolation and provision of clinical grade hMSCs for implantation: MS. Generation, purification and supply of APP96-110 and mAPP96-110 peptides, assistance with manuscript preparation: CVH. Assistance with experimental design, analysis of results and manuscript preparation: ARH. All authors approved the final version of the manuscript.

Conflicts of interest:The authors declare that they have no competing interests.Editor note: ARH is an Editorial Board member of Neural Regeneration Research. He was blinded from reviewing or making decisions on the manuscript. The article was subject to the journal’s standard procedures, with peer review handled independently of this Editorial Board member and their research groups.

Financial support:This work was supported by the Neurotrauma Research Program of Western Australia.

Institutional review board statement:All performed procedures were approved by The University of Western Australia Animal Ethics Committee (RA3/100/1460) on April 12, 2016.

Copyright license agreement:The Copyright License Agreement has been signed by all authors before publication.

Data sharing statement:Datasets analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Plagiarism check:Checked twice by iThenticate.

Peer review:Externally peer reviewed.

Open access statement:This is an open access journal, and articles are distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 License, which allows others to remix, tweak, and build upon the work non-commercially, as long as appropriate credit is given and the new creations are licensed under the identical terms.

- 中国神经再生研究(英文版)的其它文章

- The importance of fasciculation and elongation protein zeta-1 in neural circuit establishment and neurological disorders

- Promoting axon regeneration in the central nervous system by increasing PI3-kinase signaling

- Microglial voltage-gated proton channel Hv1 in spinal cord injury

- Liposome based drug delivery as a potential treatment option for Alzheimer’s disease

- Retinal regeneration requires dynamic Notch signaling

- All roads lead to Rome — a review of the potential mechanisms by which exerkines exhibit neuroprotective effects in Alzheimer’s disease