Promoting axon regeneration in the central nervous system by increasing PI3-kinase signaling

Bart Nieuwenhuis, Richard Eva

Abstract Much research has focused on the PI3-kinase and PTEN signaling pathway with the aim to stimulate repair of the injured central nervous system. Axons in the central nervous system fail to regenerate, meaning that injuries or diseases that cause loss of axonal connectivity have life-changing consequences. In 2008, genetic deletion of PTEN was identified as a means of stimulating robust regeneration in the optic nerve. PTEN is a phosphatase that opposes the actions of PI3-kinase, a family of enzymes that function to generate the membrane phospholipid PIP3 from PIP2 (phosphatidylinositol (3,4,5)-trisphosphate from phosphatidylinositol (4,5)-bisphosphate). Deletion of PTEN therefore allows elevated signaling downstream of PI3-kinase, and was initially demonstrated to promote axon regeneration by signaling through mTOR. More recently, additional mechanisms have been identified that contribute to the neuron-intrinsic control of regenerative ability. This review describes neuronal signaling pathways downstream of PI3-kinase and PIP3, and considers them in relation to both developmental and regenerative axon growth. We briefly discuss the key neuron-intrinsic mechanisms that govern regenerative ability, and describe how these are affected by signaling through PI3-kinase. We highlight the recent finding of a developmental decline in the generation of PIP3 as a key reason for regenerative failure, and summarize the studies that target an increase in signaling downstream of PI3-kinase to facilitate regeneration in the adult central nervous system. Finally, we discuss obstacles that remain to be overcome in order to generate a robust strategy for repairing the injured central nervous system through manipulation of PI3-kinase signaling.

Key Words: axon cytoskeleton; axon regeneration; axon transport; cell signaling; central nervous system; growth cone; neuroprotection; PI3-kinase; PI3K; PTEN; trafficking; transcription; translation

Introduction

Class I phosphoinositide 3-kinases (PI3Ks) are a family of enzymes that mediate signaling downstream of growth factor-, cytokine-, and integrin receptors, by producing the membrane phospholipid PIP3from PIP2(phosphatidylinositol (3,4,5)-trisphosphate from phosphatidylinositol (4,5)-bisphosphate). Activation of PI3K is the first step in a well-characterized signaling pathway that regulates a wide range of cellular functions including growth, survival and motility (Vanhaesebroeck et al., 2012). In the nervous system, it has long been implicated in the regulation of axonal specification and elongation during development (Cosker and Eickholt, 2007), and was identified in 2008 as a key pathway that could be targeted to support axon regeneration in the adult central nervous system (CNS), through genetic deletion of the enzyme PTEN (Park et al., 2008). PTEN functions to oppose the actions of PI3K. These ground-breaking studies led to a research focus on the PI3K/PTEN pathway, aimed at identifying potentially translatable approaches that might enable repair of injured axons in the adult CNS. These studies have been enormously beneficial in highlighting the importance of this pathway and identifying potential approaches for treating CNS injuries (Zhang et al., 2018).

A more recent study focused on increasing regeneration through hyperactivation of PI3K, as opposed to deletion of PTEN (Nieuwenhuis et al., 2020). This study identified additional cell biological mechanisms through which PI3K enables axon growth, not only during development, but also during regeneration after injury in the adult CNS. The study confirms PIP3as a key lipid for growth cone redevelopment and axon regeneration, and demonstrates a developmental decline in axonal PIP3as a key reason behind axon regeneration failure in the adult CNS. In this review, we summarize the neuronal signaling pathways that function downstream of PI3K and its product phosphatidylinositol(3,4,5)-trisphosphate (PI3,4,5P or PIP3) in relation to axon growth. We discuss the neuron-intrinsic mechanisms that determine the regenerative ability of axons in the adult CNS, and describe how many of these are affected by PI3K activation. We highlight that a key factor for regenerative failure is the developmental decline in PI3K and PIP3, and summarize the studies that have targeted an increase in signaling downstream of PI3K/PTEN as a means of facilitating regeneration in the adult CNS. Finally, we discuss the need for further work, and the obstacles that need to be overcome in order to generate a clinically useful strategy for repairing the injured CNS through PI3K manipulation.

Database Search Strategy

Relevant studies were identified by cross-referencing literature retrieved from internet searches using Google or PubMed, searched until March 2021. Searches were not limited.

Axon Regeneration Failure in the Adult Central Nervous System

Axons in the adult brain, spinal cord and optic nerve do not regenerate. Injury or diseases that lead to loss of axonal connectivity can therefore have devastating, life-altering consequences depending on the extent and location of the injury. CNS injuries commonly occur as a result of accidents but can also arise due to the unavoidable consequences of surgery, such as the removal of tumors closely associated with the optic nerve or spinal cord. Axon loss can also occur due to degenerative diseases such as glaucoma, which can lead to irreparable deterioration and damage of axons in the optic nerve (Williams et al., 2020). Strategies to repair injured or diseased axons in the CNS are therefore focused on stimulating robust axonal regrowth, and ultimately aimed at reconnecting axons with their correct targets. Effective repair of the injured CNS relies on axons extending over large distances through the brain, spinal cord or optic nerve before reaching their correct destinations, and re-establishing lost synapses. In addition to treating injury or disease, the ability to encourage directed regenerative growth from the retina, through the optic nerve and into the brain could also make eye transplantation a realistic possibility. Current research is primarily focused on encouraging robust, long-range growth, however in the retina and optic nerve it is equally critical to prevent the death of retinal ganglion cell (RGC) neurons which do not survive once their axonal connections are lost (Gokoffski et al., 2020).

Axon regeneration fails in the adult CNS for two principal reasons: an inhibitory extracellular environment, and a weak intrinsic capacity for axon growth. Studies aimed at overcoming the inhibitory environment have led to a number of interventions that can stimulate short-range axon growth, sprouting or enhanced axonal plasticity and these have been expertly reviewed previously (Geoffroy and Zheng, 2014; Silver et al., 2014b; Fawcett, 2015). Some of these interventions have been successful in leading to functional recovery, but an optimal intervention for repair will additionally rely on elevating the intrinsic capacity for axon growth.

Studies into the intrinsic mechanisms controlling regenerative axon growth have focused on various neuronal types in order to understand successful regeneration. The adult peripheral nervous system (PNS) is often studied as an example of neuronal populations with a good regenerative ability, whilst models of axonal injury in the CNS are studied as examples of regenerative failure with the aim of facilitating better regenerative growth, usually in the injured optic nerve or spinal cord. These studies are often paired with investigations into PNS and CNS developmental axon growth to better understand the mechanisms required for rapid and robust axon growth. Regenerative axon extension is similar to developmental growth, but is complicated by the necessity to from a new growth cone from the severed or crushed axon (Bradke et al., 2012). The development of a new growth cone may also be affected by the synaptic connections remaining after the injury; a branched axon which maintains some connectivity may be hampered by signals derived from these remaining synapses (Kiyoshi and Tedeschi, 2020). Additional challenges to axon regeneration are the large distance between the growth cone and the cell body and the polarized nature of neurons, in which the somatodendritic domain is separated from the axonal domain by membrane diffusion barriers, distinct cytoskeletal structures, and polarized transport mechanisms (Petrova and Eva, 2018). Many insightful studies of the past 20 years have been enormously informative regarding the intrinsic mechanisms controlling regenerative capacity, arising at a time when PI3K and phosphoinositide biology has also been heavily studied (Hawkins and Stephens, 2015; Fruman et al., 2017).

PI3K and PIP3 Signaling in Axon Growth

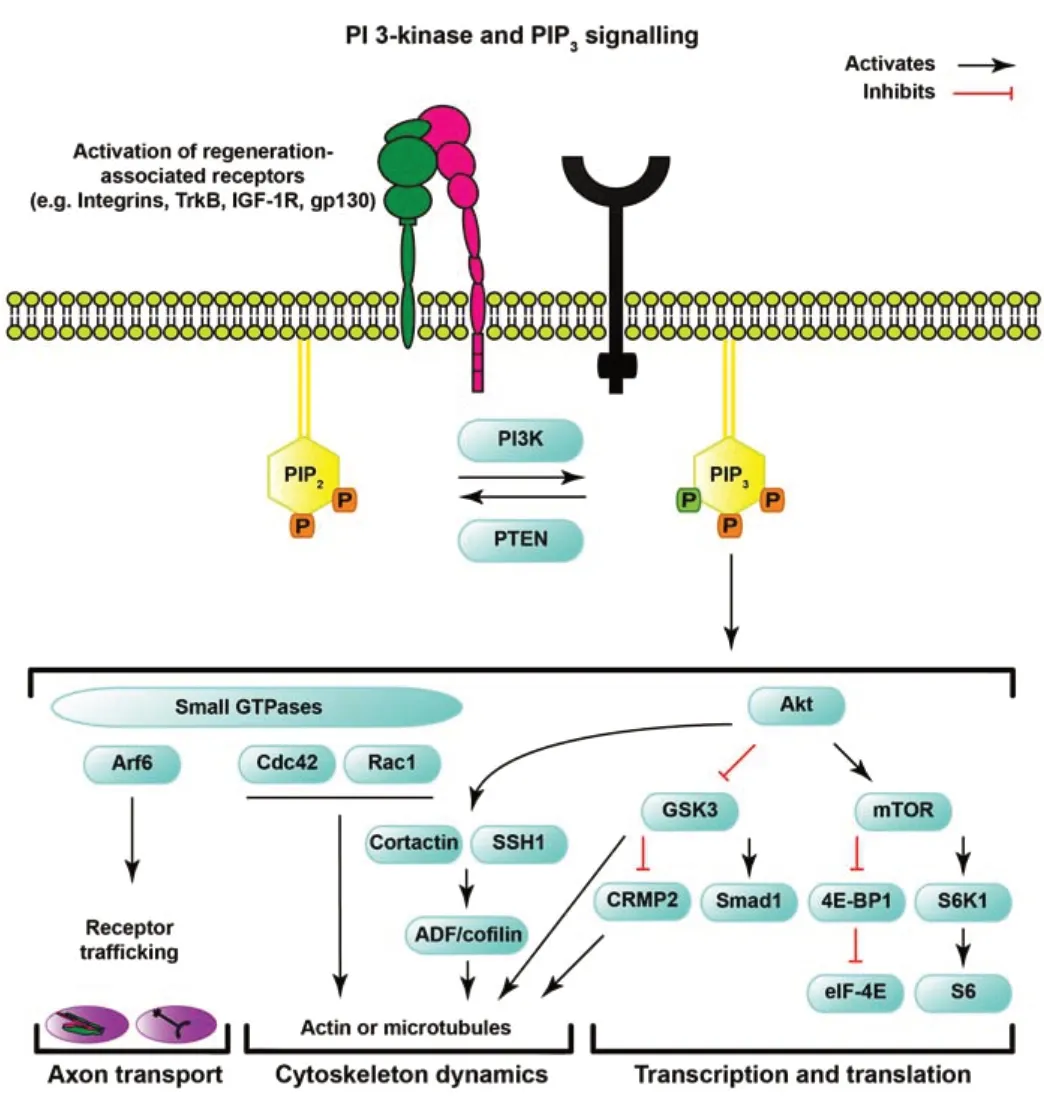

Phosphatidylinositol is a membrane phospholipid that can be modified by kinases and phosphatases at three specific hydroxyl sites (named 3,4,5). The function of PI3K is to phosphorylate the 3’ position of PI4,5P2 (PIP2) to generate PI3,4,5P3 (PIP3). In contrast, PTEN is a phosphatase that converts PIP3 to PIP2by dephosphorylating the 3’ position. It is important to note that PTEN also has enzymatic activity for additional lipids and proteins, while PI3K is thought to specifically function by phosphorylating PIP2to generate PIP3(Shi et al., 2012; Malek et al., 2017). Whilst the function of PI3K is straightforward, neuronal signaling downstream of its activity is complex and wide-ranging (Figure 1).

Figure 1|Schematic of PI3-kinase and PIP3 signaling.

PIP3signaling has been reported to regulate developmental neuronal events such as axon specification, axon elongation, and the formation of growth cone filopodia and lamellipodia (Menager et al., 2004; Zhou et al., 2004; Cosker and Eickholt, 2007), although a more recent study failed to find a direct relationship between high abundance of PIP3on specific neurites and axon specification (Kakumoto and Nakata, 2013). The involvement of PIP3in these processes has been shown indirectly using fluorescently tagged pleckstrin homology (PH)-domain reporters (Nishio et al., 2007; Henle et al., 2011; Kakumoto and Nakata, 2013). Despite the importance of PIP3, the endogenous distribution of the lipid was only recently visualized in neurons. Utilizing a lipid-specific staining protocol (Hammond et al., 2009) and anti-PIP3antibodies, the neuronal distribution of PIP3appeared to be dynamic and influenced by the developmental stage of CNS neurons. Developing cortical neurons have elevated levels of PIP3at “hotspots” in regions including the soma, along the shaft of the distal part of the axon, and at neurite growth cones; as development progresses, these enrichments decline, first in the cell body, and subsequently in the axon and growth cone (Brosig et al., 2019; Nieuwenhuis et al., 2020). This developmental down regulation of PIP3coincides with the age-related decline in regeneration capacity of CNS neurons, which is discussed in more detail in the section below.

There are four class I PI3K isoforms that contribute to the synthesis of PIP3. These are composed of a regulatory subunit and a catalytic subunit, with the p110 catalytic subunits designated p110α, p110β, p110δ and p110γ. The catalytic subunits originate from different genes (PIK3CA, PIK3CB, PIK3CD, and PIK3CG) and are expressed in various cell populations (Bilanges et al., 2019). The p110α and p110β isoforms are ubiquitously expressed throughout the body, while p110δ and p110γ are enriched in leukocytes (Hawkins and Stephens, 2015). A study using LacZ reporter mice examined the endogenous distribution of PI3K in the nervous system and found ubiquitous expression of p110α, while p110δ was expressed in peripheral nerves, DRG and the spinal cord of embryonic mice (Eickholt et al., 2007). In the CNS, the sub-cellular localization of endogenous p110δ has been described at Golgi apparatus of mature cortical neurons (Low et al., 2014; Martinez-Marmol et al., 2019) although the mRNA for p110δ is not highly expressed in cortical neurons, and overexpression directed the protein throughout these neurons, with the exception of the nucleus (Nieuwenhuis et al., 2020).

Endogenous p110α and p110δ contribute to developmental neuronal growth as well as regeneration. p110α mediates neuronal migration and neurite outgrowth of olfactory sensory neurons in chick embryo (Hu et al., 2013), whilst p110α-mediated signaling in the somatic and axonal compartment contributes to developmental axon growth and regeneration of rat DRG neuronsin vitro. In contrast, p110δ functions specifically in the axonal compartment to mediate growth cone redevelopment and regeneration, but is not required for developmental axonal extension (Eickholt et al., 2007; Nieuwenhuis et al., 2020). Interestingly, p110δ has been reported to function in a hyperactive fashion in its native state, behaving similarly to the H1047R activating mutation in p110α to generate elevated PIP3and increased downstream Akt signaling (Kang et al., 2006; Nieuwenhuis et al., 2020), suggesting that it may be required to sharply elevate axonal PIP3levels to facilitate growth cone redevelopment after axonal injury. Interestingly, inhibition of p110β only had moderate effects on the axon growth rate of DRG neurons, indicating that p110α and δ are the dominant isoforms of PI3K driving growth in these PNS neurons (Nieuwenhuis et al., 2020). Consistently, p110δ is an important component for the spontaneous axon regeneration of rat DRG neuronsin vivo, as transgenic mice expressing a D910A inactivating mutation in p110δ exhibited a decrease in axon regeneration and impaired functional motor recovery after sciatic nerve injury (Eickholt et al., 2007).

The PIP3generated by activated PI3Ks functions as a secondary messenger in a wide range of signaling pathways that are favourable for axon regeneration and survival. Elevation of PIP3, along with the simultaneous decline of PIP2mediated by the enzymatic activity of PI3Ks, causes an increase in the recruitment of proteins with PIP3-binding PH-, PX-, or FYVE domains to the plasma membrane and a decrease in molecules that bind to PIP2. Overexpression of p110δ in CNS neurons indeed leads to the activation of multiple downstream signaling cascades (Nieuwenhuis et al., 2020). Perhaps the best-characterized regeneration pathway is the recruitment and activation of Akt and subsequent downstream signaling through mTOR and phosphorylation of ribosomal protein S6, which is also involved in mediating regeneration after the genetic deletion of PTEN (Park et al., 2008; Liu et al., 2010; Geoffroy et al., 2016; Nieuwenhuis et al., 2020). S6 kinase 1 (S6K1) is also activated by signaling through this pathway, and one of its functions is to behave as negative regulator of PIP3-mediated signaling and neuronal growth (Al-Ali et al., 2017). How S6K1 attenuates PI3K signaling remains to be elucidated, but an interaction with IRS-1 (Tremblay et al., 2007; Zhang et al., 2008) could be involved. Furthermore, mTOR inactivates 4E-BP1, which in turn is inhibitory for eIF-4E, and this signaling cascade was shown to be required for axon regeneration mediated by PTEN deletion (Yang et al., 2014).

In addition to mTOR signaling, activation of Akt also relieves the inhibition of GSK3 which affects the activity of several molecules including collapsin response mediator protein 2 (CRMP2), which enhances optic nerve regenerationin vivo(Leibinger et al., 2019). However, these events represent a fraction of the cellular pathways that can be affected by signaling through Akt, which is itself part of a family of kinases that interact with numerous molecules and are subject to regulation by several post-translational modifications (Manning and Toker, 2017).

As well as signaling via Akt, PIP3(and PIP2) also signal via small GTPase proteins. These molecular switches are regulated by GAPs (GTPase-activating proteins) and GEFs (Guanine nucleotide exchange factors) that act as activators and inactivators. Many of these proteins have PH-domains, which become activated in response to elevated PIP3. The cytoskeleton regulating small GTPases Cdc42 and Rac1 are also recruited to dynamic PIP3hotspots (Tolias et al., 1995; Welch et al., 2002) and have been shown to be important for axon specification, and axon growth in developing CNS neurons (Yoshizawa et al., 2005; Sosa et al., 2006). Another influential small GTPase that is regulated downstream of PIP3and PIP2is ARF6 (Randazzo et al., 2001; Macia et al., 2008), which is governed by its GEFs EFA6 and ARNO in CNS axons, two molecules which have been targeted to increase axonal transport and regeneration in CNS neuronsin vitro(Franssen et al., 2015; Eva et al., 2017), discussed in more detail below.

PI3K and Neuron-Intrinsic Control of Regenerative Ability

Studies into the neuron-intrinsic control of regenerative ability have highlighted the importance of specific cell-biological mechanisms that are required for axon regeneration, as well as signaling pathways and genetic factors that determine regenerative ability. For more detail, some excellent in-depth reviews have been published (Curcio and Bradke, 2018; Mahar and Cavalli, 2018; Palmisano and Di Giovanni, 2018; Williams et al., 2020; Petrova et al., 2021). Here we discuss these mechanisms in relation to PI3K signaling and this is summarized inFigure 2.

Figure 2|PI3-kinase and neuron-intrinsic control of regenerative ability.

Whilst we focus on neuron-intrinsic mechanisms, it is important to note that injury responses also rely on cellcell communication, particularly with glia and immune cells. PI3K is activated downstream of cytokine receptors and plays an important role in immune cell activation (Hawkins and Stephens, 2015) as well as astrocyte activation (Cheng et al., 2020). Inflammation after CNS injury has been reviewed previously in detail (Fischer and Leibinger, 2012; Brennan and Popovich, 2018; Cianciulli et al., 2020; Greenhalgh et al., 2020; Linnerbauer and Rothhammer, 2020; Xu et al., 2020; Yazdankhah et al., 2021). Whilst these inflammatory processes occur extrinsically (to neurons), immune activation can also lead to activation of PI3K within injured neurons. This has been demonstrated in the PNS where a conditioning injury leads to the release of NADPH oxidases from inflammatory macrophages in exosomes, which are taken up by neurons leading to an increase in reactive oxygen species, which in turn leads to a decrease in PTEN activity (via cysteine oxidation) and an increase in phospho-Akt and axon regeneration (Hervera et al., 2018).

PI3K regulates axon mechanics and growth cone redevelopment

Arguably the most decisive factor determining whether an axon will regenerate is its ability to develop a new growth cone from the site of injury, as the growth cone is thought to be the primary director of axon growth (Bradke et al., 2012). Axon growth is also governed by mechanical forces generated by cytoskeletal regulation, with evidence for both the actin and microtubule cytoskeleton (as well as their linkers) as key controllers of regenerative growth (Leite et al., 2020; Rolls et al., 2021; Sousa and Sousa, 2021).

PNS dorsal route ganglion (DRG) axons grown in culture will rapidly develop a new growth cone after a laser or scratch injury (Chierzi et al., 2005; Nieuwenhuis et al., 2020), and are often studied as an example of neurons with a good axon regenerative ability. PI3K activity is required for the redevelopment of adult DRG axon growth cones, because specific PI3K inhibitors targeting either the p110α or p110δ isoforms of PI3K dramatically oppose growth cone redevelopment, even when the inhibitors are specifically applied only to the axonal compartment through microfluidic separation (Nieuwenhuis et al., 2020). Why is PI3K activity required in the axon? One possibility is for the directional targeting and insertion of growth promoting-receptors into the growth cone surface. Integrins are a good example of a regenerative growth receptor (Nieuwenhuis et al., 2018), being capable of driving robust regeneration in the adult spinal cord (Cheah et al., 2016). Integrin clustering at the growth cone is regulated by PI3K and PTEN, where asymmetric PIP3controls growth cone turning in response to chemo-attractive gradients (Henle et al., 2011, 2013). Integrins are inserted onto the growth cone surface from recycling endosomes marked by the small GTPases Rab11 and ARF6 through binding partners such as RCP and ACAP1 (Eva et al., 2010, 2012), which target integrins to the surface membrane downstream of PI3K activity to regions containing PIP3(Lindsay and McCaffrey, 2004; Li et al., 2005; Caswell et al., 2008; Hsu et al., 2020). ACAP1 is present in high levels in cultured adult DRG growth cones and is required for axon growth, but is not expressed in CNS cortical neurons (Eva et al., 2012, 2017). In addition to receptor mobilization, PI3K activity in the growth cone is also required for the transport of membrane itself from the central domain to the periphery, a process that is required for growth cone redevelopment (Ashery et al., 1996; Akiyama and Kamiguchi, 2010). Both Rab11 and ARF6 are associated with the control of regenerative ability. They facilitate the transport of integrins into regenerative PNS axons, but are restricted from adult CNS axons. Interventions that target Rab11 and ARF6 enhance the axonal transport of integrins, leading to increased regenerative ability (Nieuwenhuis and Eva, 2020). A more recent study demonstrated that Rab11 endosomes can be targeted to the distal part of axons through overexpression or activation of Protrudin, an endoplasmic reticulum resident Rab11-binding protein. Protrudin stimulates robust regeneration in the optic nerve, functioning through a number of mechanisms including via its phosphoinositide-binding FYVE domain (Petrova et al., 2020). The Protrudin FYVE domain binds to a number of phosphoinositides including PIP3 (Gil et al., 2012), and is necessary for growth cone redevelopment because inactivating mutations in this domain oppose this function (Petrova et al., 2020).

Another potential necessity for PI3K and PIP3in growth cone development is the regulation of actin. Phosphoinositides have long been identified in the control of the actin cytoskeleton, and PIP3 often colocalises with regions of f-actin polymerization (Insall and Weiner, 2001) including at the growth cones of hippocampal neurons, where it is sufficient to induce actin reorganization (Kakumoto and Nakata, 2013). The actin cytoskeleton is a critical regulator of growth cone morphology and dynamics as well as regenerative ability. The relationship between growth cone actin dynamics and axon regeneration has recently been reviewed in detail, with a number of studies demonstrating that the correct regulation of actin dynamics is crucial for axon extension, and that increasing actin dynamics can lead to enhanced regeneration in the CNS (Leite et al., 2020; Sousa and Sousa, 2021). One actin regulator that has recently been targeted to increase CNS regeneration is the actin depolymerising factor ADF/cofilin (Tedeschi et al., 2019). We highlight this here because of its regulation downstream of PI3K activity. ADF/cofilin regulates actin dynamics by severing actin filaments. Its activity is regulated by phosphorylation, being activated by dephosphorylation and inhibited by phosphorylation. This has important implications for axon regeneration, because ADF cofilin activity increases after a conditioning injury in the PNS, being dephosphorylated by the increased activity of phosphatase Slingshot homolog 1 (SSH1), rather than the decreased activity of the kinase LIMK that phosphorylates ADF/cofilin (Tedeschi et al., 2019). SSH1 was previously shown to be activated downstream of PI3K, leading to increased ADF/cofilin activity, which changes actin and membrane morphology (Nishita et al., 2004). The conditioning injury response is a well-established phenomenon that occurs after an injury to the peripheral branch of the PNS leading to substantial subcellular changes that result in an enhanced regenerative ability of the axons extending into the CNS (Neumann and Woolf, 1999). A number of studies have identified changes that occur at the level of gene expression (described in more detail below), but the control of actin dynamics represents an important mechanical process that mediates an increase in regenerative ability. In addition to SSH1, ADF/cofilin is also regulated by an interaction with Cortactin (Oser et al., 2009), another actin regulatory molecule that in turn is regulated by phosphorylation by Akt downstream of PI3K activation (Wu et al., 2014). Cortactin was recently implicated in the control of regenerative growth, by mediating inhibitory signals leading to growth cone collapse (Sakamoto et al., 2019). Whilst it is clear that PI3K activity is required locally for growth cone redevelopment (Nieuwenhuis et al., 2020), it remains to be determined whether PI3K activity regulates ADF/cofilin and actin dynamics at the growth cones of regenerating axons.

One explanation for the facilitation of regeneration through increased growth cone actin dynamics may be a permissive subcellular environment for propulsive growth from the microtubules which extend into the growth cone, which is a necessity for developmental as well as regenerative axon growth (Bradke et al., 2012). PI3K activity has been associated with the necessity for microtubule advance into the growth cone periphery for efficient axon extension, as well for microtubule dependent trafficking of membrane to the growth cone surface (Akiyama and Kamiguchi, 2010). The relationship between axon microtubule dynamics and axon regeneration has been carefully examined, with a number of studies demonstrating that microtubules can be targeted to facilitate regeneration in the adult CNS. These studies have recently been reviewed in detail (Murillo and Mendes Sousa, 2018; Rolls et al., 2021). Briefly, microtubule stability, dynamics and speed are regulated by post-translational modifications such as acetylation, tyrosination, and phosphorylation, as well as by severing or targeting of microtubule associated proteins to specific locations. Most of these mechanisms have been associated with regeneration, and/or have been targeted to enhance regeneration in the CNS (Hellal et al., 2011; Liz et al., 2014; Chen et al., 2015; Leibinger et al., 2017; Wu et al., 2020), however these have not led to a unified understanding of microtubule dynamics and axon regeneration. Some studies indicate the need for stabilized microtubules to enable axon regrowth (Hellal et al., 2011; Ruschel et al., 2015; Kath et al., 2018), while a recent study indicated that microtubules are more dynamic in the distal part of DRG axons regenerating into the spinal cord after chemogenetic stimulation (Wu et al., 2020). Additionally, pharmacological inhibition of microtubule detyrosination by parthenolide leads to an increase in dynamic microtubules, and enhanced peripheral nerve axon regeneration (Gobrecht et al., 2016). There is also evidence from anin vitrostudy that mature CNS axons with enhanced regenerative ability have no major changes in microtubule dynamics (Eva et al., 2017).

PI3K has long been associated with the regulation of axonal microtubules through downstream signaling through GSK3β and the microtubule modulators CRMP2, APC and MAP1B, which can regulate microtubule polymerization as well as stabilization and dynamics to affect axon growth (Yoshimura et al., 2005; Zhou and Snider, 2005). A number of studies have therefore meticulously examined signaling through PI3K, GSK3 and CRMP2 and reported on their involvement in the intrinsic control of regenerative ability in the CNS (Gobrecht et al., 2014; Liz et al., 2014; Leibinger et al., 2017, 2019) either through genetic deletion of PTEN (Leibinger et al., 2019) or overexpression of the natively hyperactive PI3K isoform p110δ (Nieuwenhuis et al., 2020). In addition, deletion of PTEN has also been shown to mediate enhanced regeneration through microtubule regulation, with deletion leading to an increase in tyrosinated, stable microtubules (Kath et al., 2018).

PI3K regulates transcription and translation

In the cell body, regenerative ability is controlled through signaling pathways which regulate gene and protein expression via epigenetic regulators and transcription factors as well as translation initiation factors (Curcio and Bradke, 2018). Localized protein translation also occurs within the axon and is linked to the control of regeneration (van Erp et al., 2021). As described above, regeneration relies on the redevelopment of the growth cone from the site of injury, and this is governed by the efficient anterograde delivery of materials and machinery from the cell body. At the same time, there is also communication between the axon and cell body through retrograde signaling molecules and endosomes (Petrova and Eva, 2018). A conditioning injury in the PNS leads to numerous genetic changes that elevate the neurons regenerative capacity (Neumann and Woolf, 1999).

In the CNS, growth and regeneration associated-genes are down-regulated with development and the loss of regenerative ability (Venkatesh et al., 2016; Koseki et al., 2017), and whilst injury to the PNS leads to an upregulation of regeneration-associated genes, this is generally not seen in the CNS or detected to a lesser degree (Curcio and Bradke, 2018). Studies into the transcriptional control of regeneration have identified a number of transcription factors associated with regenerative ability; some have which have been successfully targeted to enhance regeneration (Gao et al., 2004; Moore et al., 2009; Norsworthy et al., 2017). Whilst targeting single transcription factors can have beneficial effects, it is also evident that the genetic differences between neurons of varying regenerative ability are controlled by wide-ranging transcriptional events. Recent studies have therefore investigated the epigenetic mechanisms that control regeneration, identifying post-translational modifications of chromatin via both acetylation and methylation, as well as post-translational modification of transcription factors that affect the expression of regeneration associated genes and the capacity for regeneration (Weng et al., 2017; Palmisano and Di Giovanni, 2018; Palmisano et al., 2019; Chang et al., 2021). Whilst specific enzymes involved with chromatin modifications have been targeted to enhance regeneration (Oh et al., 2018; Weng et al., 2018), it is clear that the transcriptional landscape alters dramatically when neurons switch to a regenerative state (Chandran et al., 2016; Poplawski et al., 2020; Renthal et al., 2020) and specific epigenetic identities have been associated with the expression of regenerative genes (Palmisano et al., 2019). The PI3K pathway has been implicated with an increase in regenerative ability of PNS axons, being activated in response to sciatic nerve injury and signaling through GSK3 and the transcription factor Smad1 to increase regeneration (Saijilafu et al., 2013), however it has not been directly associated with an increase in sensory axon regeneration into the spinal cord after PNS injury.

PI3K activity is known to regulate the activity of influential transcription factors including NFκB, CREB and FOXO, and cancer studies have identified several chromatin modifying enzymes whose activity is regulated downstream of PI3K activity (Spangle et al., 2017; Yang et al., 2019). Neuronal deletion of PTEN certainly leads to wide-ranging changes in gene expression in RGC neurons (Sun et al., 2011), and PTENdeletion induced regeneration is attenuated by silencing of the mRNA methyltransferase Mettl14, an epigenetic regulator required for injury-induced enhancement of protein translation in the PNS (Weng et al., 2018).

“You must always remain with me,” said the emperor. “You shall sing only when it pleases you; and I will break the artificial bird into a thousand pieces.”

Deletion of PTEN is also associated with altered protein translation, via downstream signaling through mTOR. Whilst mTOR signaling can affect many cellular pathways, its effect on translation is known to be important for its regenerative effects (Yang et al., 2014). Whilst the effects on RGC neurons are most likely occurring within the cell body, localized translation can also occur within axons. There is evidence in the PNS that mTOR not only functions to upregulate local translation after an axonal injury, but also that translation of mTOR itself is upregulated in response to an injury (Terenzio et al., 2018). mTOR has also been identified at the growth cones of axons extending through the brain during development (Poulopoulos et al., 2019), however it is not known whether mTOR is present to the same extent in mature CNS axons. Given that there is a decline in local translation as CNS axons mature (van Erp et al., 2021), it is possible that mTOR expression or activity may be differently regulated in CNS axons contributing to their lower regenerative ability. The regulation of translation downstream of mTOR is complicated and has been reviewed in detail previously (Roux and Topisirovic, 2018).

Overcoming the Age-Related Decline of PIP3 Signaling in Central Nervous System Neurons

Ageing has important implications for axon regeneration (Kang and Lichtman, 2013; Geoffroy et al., 2016; Koseki et al., 2017; van Erp et al., 2021). For instance, ageing results in an increased axon growth-repulsive environment at the injury site, in particular due to enhanced reactivity by astrocytes, microglia and macrophages (Geoffroy et al., 2016). The PIP3 signaling pathway is one of the neuron intrinsic factors that becomes less active in the axon when CNS neurons mature. This is particularly supported by the finding that PIP3 levels are low in mature CNS neurons compared to developing CNS neurons that have the intrinsic capacity for developmental growth and regeneration after injury (Koseki et al., 2017; Nieuwenhuis et al., 2020). In line with the loss of PIP3 signaling, a developmental decline in the phosphorylation of S6 protein has been observed in RGC neurons (Park et al., 2008) and cortical neurons (Liu et al., 2010)in vivo.

There are various components that contribute to the decline of axonal PIP3 signaling in CNS neurons. Firstly, growthassociated cell-surface receptors such as integrins and growth factor receptors are restricted from the axons of adult CNS neurons (Hollis et al., 2009a, b; Franssen et al., 2015; Andrews et al., 2016) and these receptors are essential for the activation of PI3K. Secondly, the expression levels of all PI3K isoforms decline during the maturation of cortical neuronsin vitro(Koseki et al., 2017; Nieuwenhuis et al., 2020) and are indeed low in the adult brain (www.brainrnaseq.org/). Thirdly, high levels of active axonal PTEN are maintained in into adulthood; intriguingly, PTEN expression changes little throughout development, either at the mRNA or protein level (Koseki et al., 2017; Brosig et al., 2019). This suggests that axon growth capacity might be more tightly regulated by controlling PTEN activity rather than its expression levels, and there is evidence for this. During development, axonal PTEN activity is controlled by binding to PRG2, a protein which targets PTEN to nascent axon branch points and inhibits its activity leading to localized increases in PIP3generation (Brosig et al., 2019). Indeed, that PIP3levels decline along the developing axon shaft, but are detectable at branch points suggests that there is a close relationship between PIP3and PTEN activity, and that downregulation of PTEN activity allows for sustained PIP3required for branch generation (Fuchs et al., 2020). PTEN activity is also regulated by post-translational modifications, including being acetylated by some of the same epigenetic regulators (histone acetylases) that control gene expression and axon regeneration including CREBBP, EP300 and PCAF (Shi et al., 2012; Lee et al., 2018; Palmisano and Di Giovanni, 2018). Thus, there is an age-related decline of neuronal PIP3generation that coincides with the intrinsic regeneration capacity of CNS neurons.

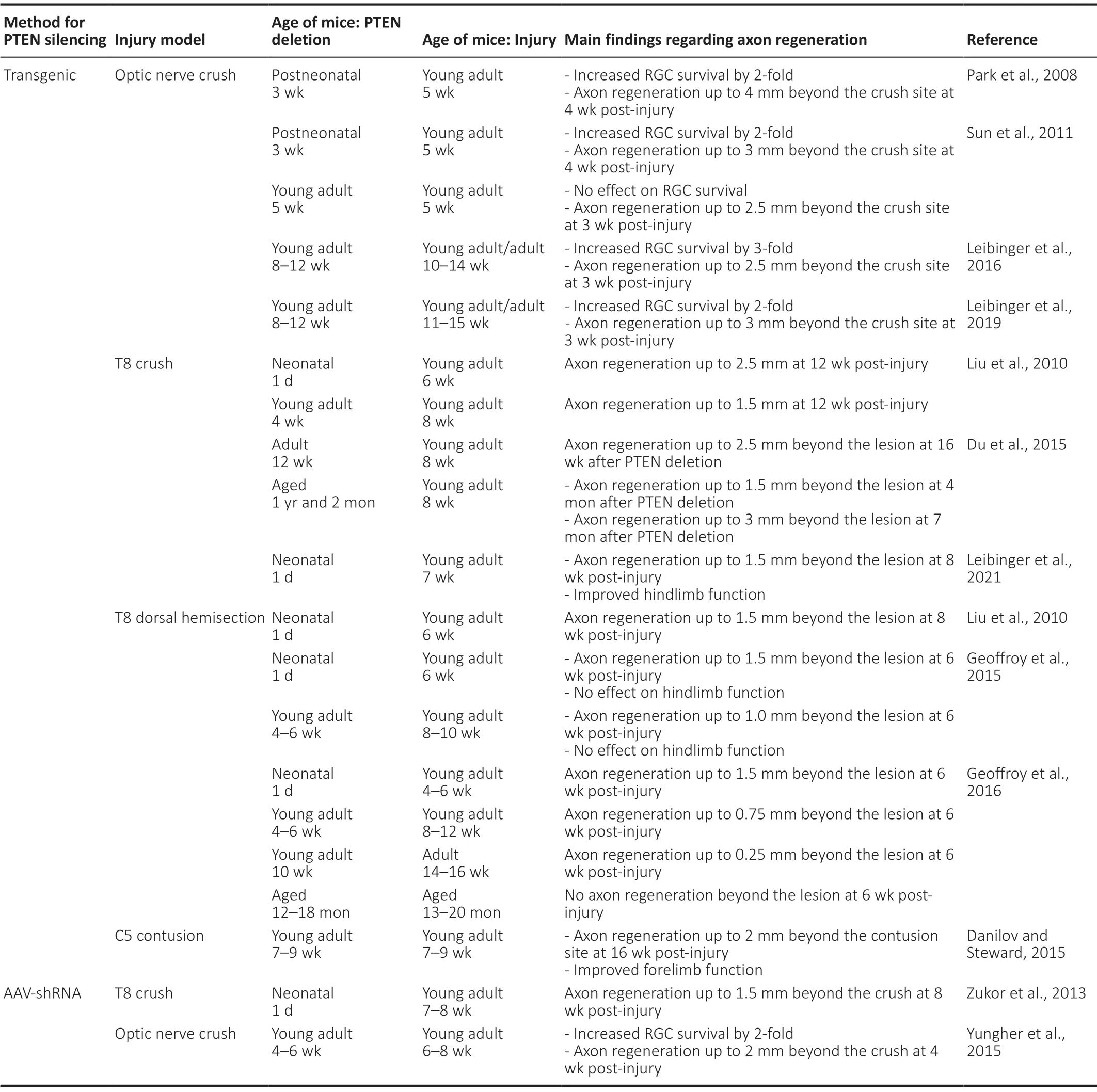

Elevating signaling through the PI3K/PIP3signaling pathway is therefore a compelling approach to promote axonal regeneration in the adult CNS. As described above, this approach was first supported in 2008 by the finding that PTEN deletion enables axon regeneration after a crush injury in the adult optic nerve (Park et al., 2008). Genetic deletion of PTEN effectively removed the brake on the PIP3signaling cascade, leading to enhanced signaling through mTOR and increased regeneration. Since this finding, variousin vivostudies have targeted this signaling pathway in different CNS injury models, demonstrating its importance in various neuronal populations. It is also important to note the effects on neuronal survival in the retina after an optic nerve injury, as axonal injury usually leads to death of RGC neurons.Table 1summarizes studies that assessed the effect of PTEN silencing on axon regeneration and neuronal survival in the corticospinal tract and optic nerve.

Repairing the Central Nervous System by Elevating PI3K Signaling

PI3K signaling is clearly beneficial for axon growth as well as redevelopment of a growth cone after axonal injury (Figure 1). The evidence from numerous neuronal and non-neuronal studies suggest that PI3K signaling affects the majority of the key mechanisms that control regenerative ability (Figure 2). However, PI3K and PIP3are developmentally downregulated in certain populations of adult CNS neurons, rapidly falling at the time when axons lose their capacity for regeneration. A number of approaches have shown that elevating signaling through the PI3K pathway leads to an increase in regeneration after a CNS injury, in both the optic nerve and spinal cord. The studies described inTable 1have elevated PI3K signaling by the targeted deletion of PTEN; In addition to these, elevated PI3K signaling has also been achieved by pharmacological inhibition of PTEN (Walker et al., 2012, 2019; Mao et al., 2013; Ohtake et al., 2014; Walker and Xu, 2014; Zhang et al., 2017). There have also been a number of approaches that have aimed to increase PI3K signaling through methods other than PTEN deletion or inhibition, with robust effects on axon regrowth either directly through increased PI3K activity (Nieuwenhuis et al., 2020), or indirectly through strategies that activate PI3K coupled receptors including combined osteopontin and IGF delivery (Duan et al., 2015; Liu et al., 2017), and activation of gp130 receptors through hyper-IL-6 treatment (Leibinger et al., 2016). There is also the approach of providing ligand and receptor in a single vector, with AAV delivery of combined TrkB and BDNF leading to striking effects on RGC survival, although this has not been tested for regenerative effects (Osborne et al., 2018).

Table 1 |Summary of studies that assessed the effect of PTEN silencing on axon regeneration and neuronal survival in the corticospinal tract and optic nerve

These studies validate the approach of elevating PI3K activity and PIP3generation as a valuable strategy for facilitating axon regeneration in the CNS. However, they have not yet yielded an intervention that permits rapid, long-range regrowth of all populations of injured axons, at a rate comparable to developmental axon growth. Why is this? Are there additional elements, which might also be addressed? An important consideration should be the exceptionally high levels of PIP3 that are present at the growth cone during development, which decline to almost undetectable amounts in adult axons (Nieuwenhuis et al., 2020). Perhaps the approaches studied have not achieved these developmental high PIP3levels. A plausible explanation for this could be the extracellular environment. PI3K elevation through p110α H1047R or p110δ expression has particularly robust effects stimulating regenerationin vitro, but more modest effects on regeneration after an optic nerve crush injury (Nieuwenhuis et al., 2020). Inhibitory CSPGs are abundantly expressed after an optic nerve crush injury (Pearson et al., 2020) and are known to oppose axon growth by attenuating PI3K (Silver et al., 2014a).

Another consideration may be the receptor/ligand engagement required for PI3K activation. This can be achieved through exogenous growth factor or cytokine expression, but relies on the abundant expression of the receptor at the site of injury. Growth factor treatments have been effective in the spinal cord, but have not yielded optimal functional recovery (Anderson et al., 2018). The developmental decline of axonal transport of receptors after development is clearly an issue (Petrova and Eva, 2018). The current evidence therefore indicates that there are low levels of PI3K coupled receptors in mature CNS axons (compared to development), low levels of activating ligands in the extracellular environment (of the injured optic nerve or spinal cord), and growth repulsive molecules such as CSPGs which oppose signaling via PI3K. This would indicate very low levels of PI3K activation in mature axons, which have become geared for neurotransmission as opposed to growth. In which case, PTEN deletion might only have limited potential due to the low levels of PI3K activity and PIP3generation at the outset.

Future approaches may need to address low levels of PI3K activation concurrently, perhaps by targeting increased receptor and ligand availability as well as overcoming the inhibitory environment. The studies described above demonstrate that the tools are now available for increasing the axonal transport of growth-receptors as well as for increasing PI3K activation though expression of p110δ. Controlled release of chondroitinase ABC as a means of overcoming inhibitory molecules is also available (Hyatt et al., 2010; Burnside et al., 2018). There are also additional approaches that might be considered for overcoming the actions of PTEN, perhaps through reducing its activity rather than its targeted deletion. As described above, PTEN activity is regulated by post translational modifications as well as by protein interactions, including reduction of activity by the histone acetyltransferase PCAF (Okumura et al., 2006), a molecule associated with the PNS regenerative response to injury. A further consideration is the availability of materials for membrane and phospholipid synthesis, with current evidence suggesting key organelles as sources of material for developmental axon growth (Petrova et al., 2021), and therefore the availability of materials may need to be addressed as well.

Author contributions:RE and BN wrote the manuscript and contributed equally. BN prepared the figures and table. Both authors approved the final manuscript.

Conflicts of interest:The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Financial support:This work was funded by the Medical Research Council (MR/R004544/1, MR/R004463/1, to RE), EU ERA-NET NEURON (AxonRepair grant, to BN), Fight for Sight (5119/5120, and 5065-5066, to RE), and National Eye Research Centre (to RE).

Copyright license agreement:The Copyright License Agreement has been signed by both authors before publication.

Plagiarism check:Checked twice by iThenticate.

Peer review:Externally peer reviewed.

Open access statement:This is an open access journal, and articles are distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 License, which allows others to remix, tweak, and build upon the work non-commercially, as long as appropriate credit is given and the new creations are licensed under the identical terms.

Open peer reviewers:George Leondaritis, University of Ioannina, Greece; Simone Di Giovanni, Imperial College London, UK.

Additional file:Open peer review reports 1 and 2.

- 中国神经再生研究(英文版)的其它文章

- The importance of fasciculation and elongation protein zeta-1 in neural circuit establishment and neurological disorders

- Microglial voltage-gated proton channel Hv1 in spinal cord injury

- Liposome based drug delivery as a potential treatment option for Alzheimer’s disease

- Retinal regeneration requires dynamic Notch signaling

- All roads lead to Rome — a review of the potential mechanisms by which exerkines exhibit neuroprotective effects in Alzheimer’s disease

- SARS-CoV-2 involvement in central nervous system tissue damage