Blunt dopamine transmission due to decreased GDNF in the PFC evokes cognitive impairment in Parkinson’s disease

Chuan-Xi Tang , Jing Chen , Kai-Quan Shao Ye-Hao Liu Xiao-Yu Zhou , Cheng-Cheng Ma Meng-Ting Liu, Ming-Yu Shi ,Piniel Alphayo Kambey Wei Wang, Abiola Abdulrahman Ayanlaja Yi-Fang Liu Wei Xu Gang Chen, Jiao Wu Xue Li,Dian-Shuai Gao

Abstract Studies have found that the absence of glial cell line-derived neurotrophic factor may be the primary risk factor for Parkinson’s disease.However, there have not been any studies conducted on the potential relationship between glial cell line-derived neurotrophic factor and cognitive performance in Parkinson’s disease.We first performed a retrospective case-control study at the Affiliated Hospital of Xuzhou Medical University between September 2018 and January 2020 and found that a decreased serum level of glial cell line-derived neurotrophic factor was a risk factor for cognitive disorders in patients with Parkinson’s disease.We then established a mouse model of Parkinson’s disease induced by 1-methyl-4-phenyl-1,2,3,6-tetrahydropyridine and analyzed the potential relationships among glial cell line-derived neurotrophic factor in the prefrontal cortex, dopamine transmission, and cognitive function.Our results showed that decreased glial cell line-derived neurotrophic factor in the prefrontal cortex weakened dopamine release and transmission by upregulating the presynaptic membrane expression of the dopamine transporter, which led to the loss and primitivization of dendritic spines of pyramidal neurons and cognitive impairment.In addition, magnetic resonance imaging data showed that the long-term lack of glial cell line-derived neurotrophic factor reduced the connectivity between the prefrontal cortex and other brain regions, and exogenous glial cell line-derived neurotrophic factor significantly improved this connectivity.These findings suggested that decreased glial cell line-derived neurotrophic factor in the prefrontal cortex leads to neuroplastic degeneration at the level of synaptic connections and circuits, which results in cognitive impairment in patients with Parkinson’s disease.

Key Words: cognitive impairment; degree centrality; dendritic spine; dopamine transmission; dopamine transporter; glial cell line-derived neurotrophic factor;Parkinson’s disease; prefrontal cortex; synaptic plasticity

Introduction

The rising pandemic of Parkinson’s disease (PD) due to ever-changing socioeconomic circumstances and aging population (Dorsey et al., 2018),as well as the considerable inter-individual differences (e.g., the onset and progression of clinical symptoms, early surveillance, and diagnosis) has presented significant challenges.The hallmark motor symptoms induced by dopaminergic neuron (DAN) loss in the basal nuclei were once considered the mainstay of PD diagnostic criteria (Jankovic, 2008).However, an epidemiological study has shown that non-motor symptoms begin years before the severe decline in movement and physical tasks (Williams-Gray et al.,2007), albeit in a less noticeable manner.Consequently, cognitive impairment,the most severe non-motor feature that is often more debilitating than motor symptoms for PD patients and their caregivers, has become more recognized in patients with PD (Burn et al., 2014).However, cognitive dysfunction is not a sufficiently distinct feature of PD to aid in early PD detection (Tolosa et al.,2009).Thus, there is an urgent need to pursue validated clinical biomarkers to predict and evaluate the cognitive deterioration and potential progression of PD and advance our knowledge of the underpinnings of the disease.

Blood- or cerebrospinal fluid-based biomarkers, such as α-synuclein (Tokuda et al., 2006), microtubule-associated protein tau, amyloid-beta (Wang et al., 2013), and homocysteine (Isobe et al., 2005), have been linked to the severity of PD.These biomarkers were selected because there is agreement that the initial pathogenesis of PD involves a series of events that culminate in DAN death (Olanow, 2007).Indeed, alterations in brain functional network connections may be the primary mechanism underlying early cognitive neurodegeneration in PD (Caviness, 2014), rather than the exclusive death of DANs.This has led to inconsistent findings, such as those that indicate no changes in the tau levels in the cerebrospinal fluid, providing limited utility for predicting the progression of PD (Kang et al., 2013; Youn et al., 2018).Because of such contradictory findings and the lack of specificity of diseaseand symptom assessments, there are currently no serum biomarkers for the diagnosis of PD.We suggest that neurotrophic factor deficiency may be a more plausible mechanism because links between changes in the microenvironment and oxidative stress, inflammation (Bellaver et al., 2017),mitochondrial dysfunction, misfolded protein aggregation (Chmielarz et al.,2020), and transmitter disorder (Halliday et al., 2014) have been consistently reported.We further propose that neurotrophic factor insufficiency is the cause of PD.Specifically, glial cell-derived neurotrophic factor (GDNF) is a critical factor in promoting DAN survival and differentiation of DANs (Lindholm et al., 2007) and is a potent inhibitor of DAN mortality and degeneration.Recently, studies have reported that serum GDNF levels are significantly correlated with cognitive impairment in patients with Alzheimer’s disease(Sharif et al., 2021), and higher serum GDNF levels are associated with better cognitive performance in patients with deficit schizophrenia (Tang et al.,2019b).These findings suggest that the GDNF level is a promising candidate for assessing cognition status.However, because the specific mechanism of GDNF in executive functions is currently uncertain, no studies have offered direct evidence for a relationship between GDNF levels and cognitive performance in patients with PD.

Executive functions, which encompass the higher-order control of various goal-directed behavioral processes (Rodriguez-Oroz et al., 2009; Talpos and Shoaib, 2015) (i.e., working memory, planning and reasoning, and inhibition control), are also impaired in early PD but often obscured by motor features (Goldman and Sieg, 2020).The prefrontal cortex (PFC) is a primary contributor to executive functions (Nyberg, 2018).Indeed, imaging studies have consistently shown that the specific regions of the PFC are consistently activated in response to different elements of the executive process (Kirsch, 2011; Nyberg, 2018).Dopamine (DA), produced by DANs in the ventral tegmental area (VTA) (Murty et al., 2017), supplies the PFC as a potent modulator and has an inverted U-shaped relationship with executive function performance (Bilder et al., 2004; Simioni et al., 2017; Tang et al.,2019a) by fine-tuning the neuronal activity and plasticity of the PFC (Popescu et al., 2016).This indicates that both insufficient and excessive DA activity impairs PFC functions (Durstewitz et al., 2000).Based on the detection of 18F-dopa, it has been revealed that the loss of dopaminergic cortical input is also an early hallmark of PD (Moore et al., 2008).As previously stated, GDNF has high selectivity for DANs and has been shown in a PD animal model to enhance DA system recovery (Sterky et al., 2013).However, the basal GDNF level in the midbrain is low (Pochon et al., 1997), and the principal source of GDNF is retrogradely conveyed by DANs (Tomac et al., 1995), which indicates that endogenous midbrain GDNF is a retrograde factor of other regions,including the PFC.Considering the above findings of GDNF reduction in PD,loss of DA transmission in the PFC, and the retrograde factor characteristic of GDNF, we hypothesized that during the early stages of PD, GDNF deficiency in dopaminergic axon terminals, particularly in the PFC, plays a vital role in executive dysfunction.The underlying mechanism by which GDNF reduction in the PFC, as the targeted region dominated by dopaminergic axons,promotes morphological and functional changes in PFC neurons that lead to cognitive-behavioral abnormalities is uncertain.Therefore, we aimed to examine the relationship between serum GDNF levels and cognitive status in patients with PD.

Methods

Participants

This case-control study was approved by the Ethics Committee of the Affiliated Hospital of Xuzhou Medical University (approval No.XYFY2017-KL047-01; Additional file 1) on May 6, 2020.All participants provided written informed consent.This study followed the STRengthening the Reporting of OBservational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) guidelines (von Elm et al.,2007; Additional file 2).

Participants were recruited from the Affiliated Hospital of Xuzhou Medical University between September 2018 and January 2020.Individuals were eligible if they had been clinically diagnosed with PD by two neurologists by fulfilling the United Kingdom-PD Society Brain Bank criteria (Hughes et al.,2001) and had not undergone any neurosurgical treatment.The exclusion criteria were: non-idiopathic Parkinsonism, dementia with Lewy bodies,severe brain injury, serious illness (e.g., heart failure, psychiatric illness, and malignancy), and cognitive impairment precluding informed consent.Healthy age-matched and sex-matched control individuals were recruited from the spouses and friends of PD participants.Participants were assessed using a variety of questionnaires covering demographic information and clinical characteristics.Their usual daily medication was not restricted.We recorded the lifestyle habits of all participants, which included cigarette smoking,alcohol consumption, chronic diseases (e.g., hypertension and diabetes), and clinical PD data (i.e., age at onset, disease duration, Hoehn-Yahr stage (Hoehn and Yahr, 1967), and medication use).Cognitive evaluations were conducted using the Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE) (Burdick et al., 2014), the Montreal Cognitive Assessment (MoCA) (Nasreddine et al., 2005), the Clinical Dementia Rating (CDR) (Lim et al., 2005), part of the Alzheimer’s disease assessment scale (ADAS-cog) (Kueper et al., 2018), and the Trail Making Test-A (TMT-A) (Bowie and Harvey, 2006).The specific cognitive domains evaluated by the above scales were disassembled to provide a comprehensive analysis of cognitive function.The levodopa equivalent daily dose (LEDD) was calculated according to conversion factors (Tomlinson et al., 2010).

Animals

All experiments were performed in accordance with the guideline of the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals published by the United States National Institutes of Health and the related ethical regulations of Ethics Committee of Experimental Animal Center of Xuzhou Medical University (approval Nos.L20210226140 [March 2, 2021] and L20210226312 [February 28,2021]).Female mice are not suitable for Parkinson model mice due to neuroprotective role of estrogen (Chen et al., 2019), so we selected only male mice.All male wild-type C57BL/6J mice (10–12 weeks old, weighing 23–25 g)were housed in constant humidity (45–65%) and temperature (18–26°C) in pathogen-free cages with food and water available ad libitum on a 12-hour light/dark cycle.The mice were provided by the Laboratory Animal Centre of Xuzhou Medical University (license No.SYXK [Su] 2020-0048).All experiments were conducted and reported according to the Animal Research: Reporting ofIn Vivo

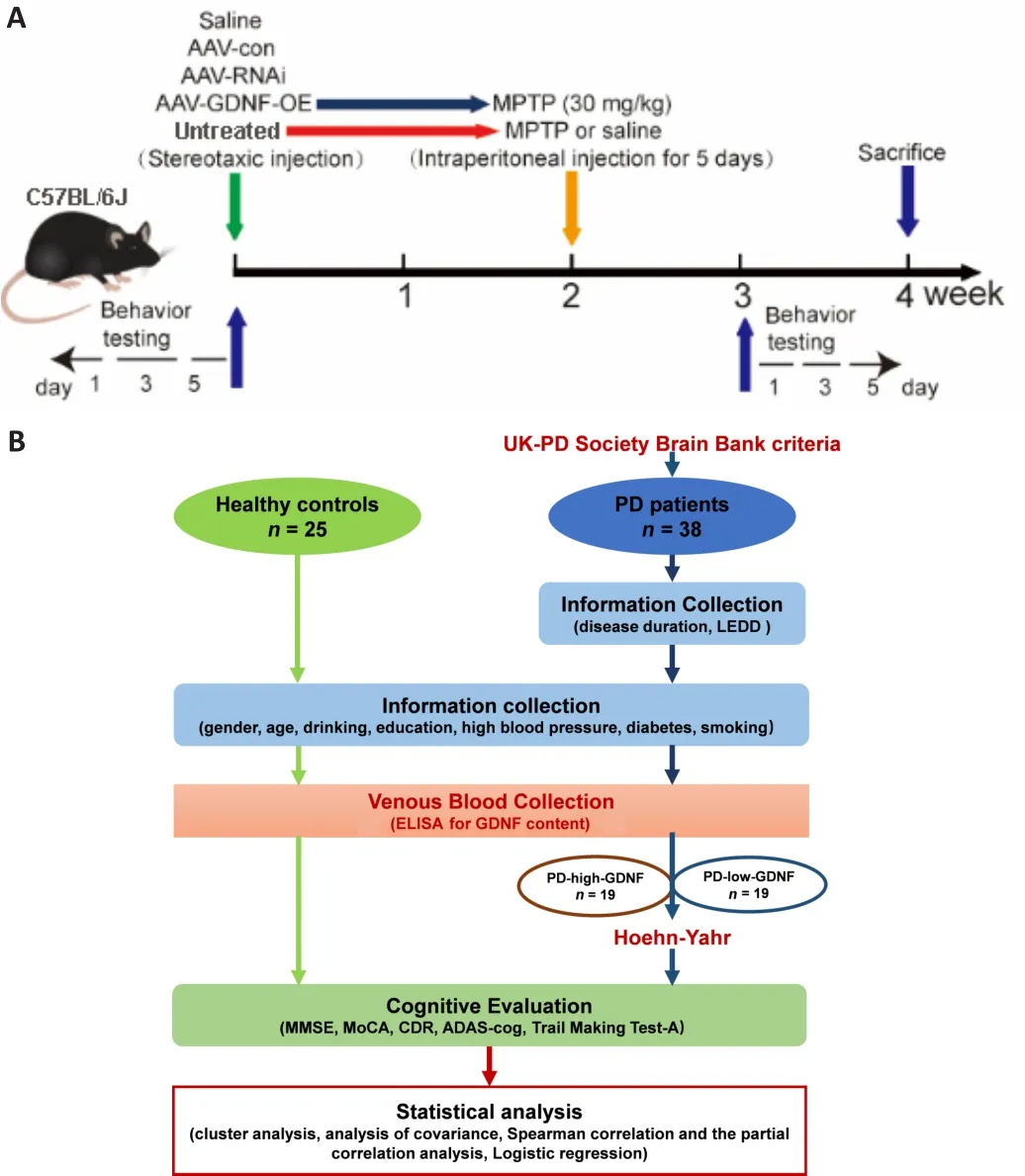

Experiments guidelines (Percie du Sert et al., 2020).The experimental process is shown in Figure 1A.1-Methyl-4-phenyl-1,2,3,6-tetrahydropyridine PD model

All mice were randomly divided into 1-methyl-4-phenyl-1,2,3,6-tetrahydropyridine (MPTP) and control groups (12 mice/group).The subacute PD models were established by intraperitoneal administration of 30 mg/kg MPTP (dissolved in sterile normal saline, with the final concentration 6.8 mg/mL) (Cat# M0896, Sigma, St.Louis, MO, USA) per day for 5 consecutive days.We administered 0.12 mL of normal saline to the control mice.

Stereotaxic surgery and adeno-associated virus injection

After anesthesia by intraperitoneal injection of pentobarbital sodium(45 mg/kg), all mice randomly underwent stereotaxic surgery to infuse the adeno-associated virus (AAV) injection (AAV-GDNF-overexpression [AAV-GDNF],AAV-GDNF-RNAi [AAV-RNAi], or AAV-control [AAV-con]) into the PFC (anteriorposterior [AP]: +1.78 mm; medial-lateral [ML]: +0.15 mm; dorsal-ventral [DV]:–2.25 mm] (Franklin and Paxinos, 2008).Two weeks later, half of mice in the AAV-GDNF and AAV-con groups were administered MPTP (30 mg/kg) via an intraperitoneal injection for 5 consecutive days and used as the MPTP + GDNF and MPTP groups.A trace syringe connected to a micro-injection pump was inserted into the target brain region for the viral infusion and maintained in place for 2 minutes for stabilization.After stabilization, we performed infusion at 0.1 μL/minute, followed by a 15-minute resting period to permit AAV diffusion.The AAV was unilaterally injected into the PFC.After infusion,the syringe was slowly removed, and the scalp was sutured.Postoperatively,mice were kept warm and provided with peanuts as a nutrient supply.After 4 weeks, we performed the perfusion and histology procedures.

Y-maze test

The Y-maze (Zheng Hua Tech Co., Ltd., Hefei, China) comprised three gray opaque arms orientated at 120° angles from each other and was used to assess short-term spatial working memory by allowing the mice to explore all three arms of the maze (Kraeuter et al., 2019).Spontaneous alternation was defined as consecutive entries into all three arms.The numbers of arm entries and alternations were recorded to calculate the percentage of alternation behavior over 5 minutes.The alternation percentage was calculated using the following formula: alternation (%) = number of alternations/(total number of arm entries – 2) × 100.A high alternation percentage indicates good working memory because it indicates that the mouse could recall which arms it had already visited.

Passive avoidance test

The passive avoidance test (PAT) was designed according to the preference for darkness in mice and was used to evaluate passive avoidance learning memory in mice (Salimi and Pourahmad, 2018).A retractable door divided the apparatus (ZH-500x, Zheng Hua Tech Co., Ltd.) into two compartments of the same size (20.3 × 15.9 × 21.3 cm): a brightly lit compartment and a dark compartment.The dark compartment was equipped with a grid floor programmed to control electricity through which a foot shock could be delivered.Upon entering the dark compartment, mice received an electric shock.Mice underwent two independent trials: a training session and a test session conducted 24 hours later.The mouse was placed in the light compartment during the training session, and 10 seconds later, the door was opened.The mouse was allowed to move freely around the device.After 3 minutes of habituation, the mouse was removed.This process was repeated for each mouse.The mouse was then placed into the light compartment first.As soon as the mouse entered the dark compartment, an electric shock was delivered.The testing session was repeated 24 hours later.However, for this session, a foot shock was not delivered.The latency to enter the dark compartment was recorded, with a cutoff time of 300 seconds.

Sampling mouse serum from the retro-orbital sinus

Mice were anesthetized by an intraperitoneal injection of pentobarbital sodium (45 mg/kg).When mice achieved the ideal anesthetic state, an inner canthus puncture was performed after providing iodine volts disinfection around the eye.After sample collection, the blood was centrifuged at 1000×g

for 10 minutes at 4°C to isolate the serum supernatant for serum GDNF analysis.Tissue processing and histology

Immediately following the blood withdrawal procedure, the mice were perfused transcardially with 35 mL of 0.1 M of pH 7.4 phosphate buffer saline(PBS), followed by 35 mL of 4% formaldehyde in PBS.The brains were postfixed for 24 hours with 4% paraformaldehyde and then transferred to 30%sucrose for cryoprotection.The left hemispheres of the mouse brains wereremoved and dissected on ice.Samples from the PFC were homogenized in lysis buffer (Beyotime, P0013B, Shanghai, China) containing a protease/phosphatase inhibitor cocktail (Beyotime, P1050).The homogenate was centrifuged (12,000 ×g

) at 4°C for 30 minutes, and the supernatant was collected and stored at –80°C.Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay

Mice and human serum samples and ground mice brain tissue supernatant were detected using enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) (GDNF ELISA Kit [human]: Cat# SEA043 Hu, Cloud-Clone Corp, Wuhan, China; GDNF ELISA Kit [mice]: Cat# ml037698, Shanghai Enzyme-linked Biotechnology Co., Ltd., Shanghai, China; DA ELISA Kit [mice]: Cat# NM-0355R2, MEIMIAN,Yancheng, Jiangsu, China).The protocol was performed according to manufacturer instructions.The optical density values were detected using a microplate reader (BioTek, Hercules, CA, USA).

Immunohistochemistry

Brain tissues were embedded in an optimal cutting temperature compound(4583, Tissue-Tek, Sakura, Tokyo, Japan), serially coronally sectioned at a thickness of 20 μm using a cryostat (CM1950, Leica, Wetzlar, Germany),and free-floating sections were stored in a cryoprotection solution (0.1 mM PBS, ethylene glycol, and sucrose) at –20°C.All sections were prepared for immunohistochemistry according to the following methods: sections were rehydrated in Tris-buffered saline (TBS) three times for 10 minutes each;blocked in TBS containing 0.5% Triton X and 5% normal donkey serum for 60 minutes; incubated with primary antibodies (anti-dopamine transporter[DAT], rabbit, 1:500, Sigma, St.Louis, MO, USA, Cat# AB1591P, RRID:AB_90808) overnight at 4°C; washed with 0.1 M PBS three times for 10 minutes each following morning; incubated with secondary antibodies goat anti-rabbit immunoglobulin G (IgG) H&L (Alexa Fluor® 594, 1:1000, Abcam,Cambridge, UK, Cat# ab150080, RRID AB_2650602) for 3 hours; washed in TBS three times for 10 minutes each; and mounted on a glass slide and coverslipped with mounting medium.Immunofluorescence was imaged digitally using a fluorescent microscope (BX-43, Olympus, Tokyo, Japan) and a confocal microscope (FV10i, Olympus).Images were digitally processed using Photoshop 23.3.0 (Adobe, San Jose, CA, USA) or ImageJ 1.8.0 (National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD, USA) (Schneider et al., 2012) software.

Immune electron microscopy

Mice were anesthetized by intraperitoneal administration of pentobarbital sodium (45 mg/kg) and subsequently perfused transcardially with 4%formaldehyde and 0.5% glutaraldehyde.The PFC was dissected and immersed in the same fixative with 4% paraformaldehyde, 0.5% glutaraldehyde, and 0.2% picric acid for 4 hours.The tissue blocks were dehydrated by increasing ethyl alcohol solution concentrations (50%, 70%, 80%, 85%, 95%, and 100%each for 15 minutes).The tissue blocks were then penetrated in a gradient and embedded using the LR White Kit (Agar, 14383-UC, Essex, UK).The blocks were sectioned into 90 nm-thick sections using an ultramicrotome.Sections were treated with 0.1 M PBS for 5 minutes and 1% glycine for 30 minutes and immersed in a blocking buffer (0.1% gelatin + 1% bovine serum albumin + 0.1% Saponin) to minimize non-specific antibody binding.We used 0.04% Triton X-100 to enhance antibody penetration.Sections were treated overnight with an anti-DAT antibody (rat, Cat# sc-32259, RRID: AB_627402,Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Dallas, TX, USA) diluted to 1:10 in blocking buffer at 4°C.Sections were rinsed after primary antibody incubation and placed in 10 nm colloidal gold (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA) for 1 hour.Sections were extensively rinsed four times in blocking buffer (0.1% gelatin+ 1% bovine serum albumin + 0.1% Saponin) for 20 minutes each and fivetimes in PBS for 2 minutes each, postfixed in 1% glutaraldehyde (10 minutes),and rinsed again in PBS.Sections were counterstained with uranium dioxide acetate and lead citrate for 3 minutes each, rinsed again five times in PBS for 2 minutes each, and examined on a Tecnai G2 Spirit Twin transmission electron microscope (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA).

Golgi-Cox staining

Mice were anesthetized by intraperitoneal administration of pentobarbital sodium (45 mg/kg) and subsequently perfused with 4°C PBS being killed.The brains were removed from the skull carefully and as quickly as possible.The pia mater was carefully removed, and the brain was placed in a constant volume mixture of solutions A and B.The impregnation solution was replaced the following day and stored at room temperature (20–25°C) for 2 weeks in the dark.The brains were then transferred to solution C.The buffer was replaced on the second day, and the brains were stored at 4°C for 96 hours in the dark.The brain was sectioned coronally using a vibrating microtome at a thickness of 100 μm.Each section was mounted on a gelatin-coated microscope slide using solution C, and the slides were allowed to dry naturally at room temperature (20–25°C) in the dark.The slices were rinsed twice with deionized water for 5 minutes each and incubated with a mixture of solutions D and E and deionized water for 10 minutes.After gradient dehydration, xylene transparence and gum sealing were performed according to the instructions of the Golgi-Cox Stain Kit (FD NeuroTech, Columbia, MD,USA).Finally, the sections were imaged using a digital scanning sectioning system (Olympus VS120).Sholl analysis using the ImageJ software was used to quantitatively analyze the morphological characteristics of the imaged neuron.For example, the differences in the number of dendritic intersections were correlated with the distance from the cell body.

Western blot assay

The protein level in the supernatant from brain tissue was determined using a Micro bicinchoninic acid protein assay kit (23235, Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA) using bovine serum albumin as the standard.The proteins were separated using sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis and electrophoretically transferred to a nitrocellulose or polyvinylidene fluoride membrane (10600023, GE Amersham Biosciences,Little Chalfont, Buckinghamshire, UK).The membrane was blocked for 2 hours at room temperature (20–25°C) using a blocking buffer (5% bovine serum albumin).The membrane was incubated with appropriate dilutions of primary antibodies (anti-GDNF: Cat# ab176564, Abcam, Cambridge, UK; anti-DAT: AB1591P, RRID: AB_90808, Sigma, St.Louis, MO, USA; anti-synapsin:Cat# 11568, RRID: AB_10760506, SAB, College Park, MD, USA; postsynaptic density protein-95 (PSD95): Cat# 3450S, RRID: AB_2292883, CST, Boston, MA,USA) in blocking buffer at 4°C overnight.The following day, the membrane was washed with TBS three times for 5 minutes each and subsequently incubated with secondary antibodies (IRDye® 800CW goat anti-rabbit IgG secondary antibody: Cat# 926-32211, RRID: AB_621843; IRDye® 680RD goat anti-mouse IgG secondary antibody: Cat# 926-68070, RRID: AB_10956588;1:15000, LI-COR, Lincoln, NE, USA) for 2 hours at room temperature (20–25°C).The immunoblots were developed using the Odyssey Imager 5359 (LI-COR).Immunoblot analysis was performed using the ImageJ software.

DA dynamics recording

In vivo

fiber photometry was performed to measure the activity of dopaminergic axon terminals from the VTA.Photometry is the most commonly used visual approach alongside genetically-encoded calcium indicators (Sun et al., 2018).The mice were injected with an AAV-encoding G protein-coupled receptor-activation-based-DA (AAV2-CaMKIIa-DA1h, 500 nL; Brain VTA, Wuhan, China).The optic fiber was implanted with the tip placed over the dopaminergic axon terminal in the target brain region (AP:+1.78 mm, ML: +0.25 mm, DV: –2.05 mm) 3 weeks after the virus injection.The stimulation electrode was embedded in the VTA (AP: +3.20 mm, ML:+0.45 mm, DV: –4.30 mm).The fluorescence signal changes before and after electrical stimulation of the VTA (100 Hz, 1 ms wave width, 2 seconds duration, 100 μA intensity, 5–6 stimulations) were recorded using an optical fiber recording system (Thinkertech Nanjing Biological Technology Co., Ltd.,Nanjing, China).The fiber photometry recording data were then processed using the MATLAB R2020b software (The MathWorks, Inc., Natick, MA, USA).High-performance liquid chromatography

DA concentration was evaluated using a high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) system (Agilent, 1290 Infinity, Santa Clara, CA, USA).For the preparation of the standard solutions, an appropriate amount of DA reference solution of quality control standard was accurately weighed and dissolved in ultra-pure water.The standard stocks at 10 mM were prepared and stored at –20°C in the dark.In addition, an appropriate amount of caffeic acid (CA) reference substance was accurately weighed and dissolved in ultrapure water.We prepared 1 mg/mL (internal standard of CA) of CA reserve solution.The artificial cerebrospinal fluid (ACSF) was prepared, i.e., NaCl 6.279 g + KCl 0.216 g + CaCl0.353 g + MgCl0.488 g + NaHCO1.932 g + glucose 0.6 g + NaHPO0.358 g were dissolved in 1000 mL of ultra-pure water.A 90 μL sample preparation of ACSF was accurately measured, and 10 μL of the standard solution was added to prepare the standard sample.An appropriate amount of the medial PFC was obtained, accurately weighed, immediately cut with ophthalmic shears at a ratio of 1 mg: 50 μL using normal cold saline,and homogenized in an ice bath with a tissue homogenizer to prepare a tissue homogenate of 20 g/L.The tissue homogenate was measured and added to 10 μL of CA (2000 ng/mL for tissue determination).After vortexing for 10 seconds, 100 μL of cold acetonitrile was added.After swirling for 1 minute,100 μL of supernatant was cryogenically centrifuged at 14,000 ×g

at 4°C for 10 minutes, and 50 μL of sodium tetraborate (100 mM) and 50 μL of benzoyl chloride (2% acetonitrile solution) were added successively.A derivation reaction was performed after swirling for 5 minutes at room temperature (20–25°C), and cryogenic centrifugation was performed at 14,000 ×g

at 4°C for 10 minutes.The sample volume of supernatant was 10 μL for tissue analysis.The MassHunter GCMS Data Acquisition software (Agilent Technologies, Inc., Palo Alto, CA, USA) was used to collect HPLC-mass spectroscopy (MS)/MS data.The collected data were qualitatively and quantitatively analyzed.Electrophysiological whole-cell patch-clamp recordings

Mice were decapitated by pentobarbital sodium (45 mg/kg) anesthetization,and transverse PFC slices (400-μm thickness) were prepared using a vibratome in ice-cold ACSF (Sigma-Aldrich, St.Louis, Missouri, USA).Slices were placed in the recording chamber (RWD Life Science Co., Ltd., Shenzhen,China), which was superfused (3–4 mL/min) with ACSF at 32–34°C.The field excitatory postsynaptic potential (fEPSP) of the PFC was recorded by placing a tungsten wire electrode on layer V and an ACSF-filled glass extracellular recording electrode on layers II–III of the medial PFC.The test stimuli consisted of monophasic 0.1-ms pulses of constant currents (with intensity adjusted to produce 50% of the maximum response) at a frequency of 0.033 Hz.Dipulse stimuli were presented at intervals of 20, 40, 60, 80, 100, 150,200, 400, 600, and 800 ms and 1 second.The ratio of the amplitude of the second fEPSP to that of the first fEPSP was calculated.The intensity of the stimulus was determined by measuring 50% of the maximum rising fEPSP phase slope.Signals were recorded steadily for 15 minutes as a baseline.All drugs were dissolved in ACSF and administered by switching the perfusion from the control ACSF to the drug-containing ACSF.Long-term potentiation(LTP) was induced by high-frequency stimulation (HFS; 100 Hz, 1000 ms × 2,30 seconds interval).LTP was recorded 30 minutes after HFS.

Magnetic resonance imaging

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) scans were acquired on a 7.0T Biospcc 70/20 MR spectrometer (Brook GmbH, Karlsruhe, Germany).Mice were anesthetized using 5% isoflurane (RWD Life Science Co., Ltd., Shenzhen,Guangdong, China) and maintained with 1.1–1.5% isoflurane under spontaneous breathing conditions.The animal was secured in a custommade stereotaxic holder (RWD Life Science Co., Ltd.) with ear and tooth bars.Data were acquired using the following parameters: T2-weighted image parameters: scan thickness = 0.7 mm, repetition time = 2500 ms, echo time= 35 ms, imaging frequency = 300.3206893 ms, imaging core: 1H, and image matrix size =256 × 256; diffusion tensor imaging parameters: echo time =0.68267 ms, repetition time = 2800 ms, dispersion time = 12 ms, dispersion coding time = 5 ms, total sample dispersion direction = 30,b

-value = 2040.17 s2, in-plane resolution = 0.140625 mm, and scan thickness = 0.8 mm.The brain (excluding the olfactory bulb and cerebellum) was manually segmented according to the T2*-weighted images.For quantitation of MRI parameters,bilateral regions of interest (ROIs), including the whole brain, striatum,substantia nigra, motor cortex, thalamus, hippocampus, PFC, and corpus callosum, were manually drawn on each animal using the Waxholm Space mouse template (Chongqing Siying Technology, Chongqing, China).Mice MRI data were preprocessed using the Matlab software and involved removing the first 10 time points, slice-time correction, head movement correction,and statistical parametric mapping for registration processing.The scalp was removed using a three-dimensional-pulse-coupled neural network, and the linear trend was removed.The filter was calibrated to 0.01–0.08 Hz, and 24 head movement parameters were returned.The Data Processing and Analysis for Brain Imaging toolbox (DPABI RRID:SCR 010501) was used to generate functional connection maps.The degree centrality (DC) of the whole brain and each ROI was calculated to examine node centrality in the DC analysis.Statistical analysis

All clinical data were statistically analyzed using IBM SPSS 20.0 (IBM, Armonk,NY, USA).Firstly, k-means was used for the cluster analysis based on the serum GDNF results (domain clustering) and cognitive symptoms (symptom clustering).Because the sample size was balanced, we set an initial cluster center of k = 2.The subjects in the PD group were clustered into PD-high-GDNF and PD-low-GDNF groups.We performed subgroup analyses of each variable of both the clustering and control groups.Data distributions were assessed for normality using the Shapiro-Wilk test.The descriptive statistics of the quantitative data are presented as means ± standard deviations or interquartile ranges.The clinical and demographic features in the three groups were compared using the Kruskal-WallisH

test.Chi-square, likelihood ratio, and Mann-WhitneyU

tests were used to examine differences between groups.Analyses of covariance were conducted to test whether the means of the dependent variables were equal across levels of the categorically independent variable while controlling for the effects of other continuous variables that were not of primary interest.Spearman correlation and partial correlation analyses were used to examine associations among variables,such as the serum GDNF concentration and cognitive status (i.e., MMSE and MoCA scores).Moreover, odds ratios (ORs) were estimated to identify the association between GDNF level and cognitive function using univariate/multivariate logistic regression models.Using the cognitive level as assessed by the MMSE/MoCA score, we used no cognition dysfunction (MMSE score≥ 27; MoCA score ≥ 26) and mild cognitive impairment (MMSE score ≥ 21;MoCA score ≥ 18) as a control group and moderate cognitive disorder (MMSE score < 21; MoCA score < 18) as a validation group.Data from these groups were analyzed using receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curves.Youden’s index determined the ‘optimum’ cutoff point, and aP

< 0.05 was considered significant.Logistic regression was used to predict the risk of developing PD and cognition dysfunction based on patients’ observed characteristics(e.g., age, sex, education, lifestyle habits, and GDNF blood test results).The correlation between the serum level of GDNF and cognitive assessment scores as measured using the MMSE and MoCA was examined using the Pearson correlation coefficient.All graphical representations of data were generated using Prism 8.0.2(GraphPad, La Jolla, CA, USA, www.graphpad.com) in combination with Photoshop 23.3.0 and Illustrator 23.0.3 (Adobe, San Jose, CA, USA).All data are presented as means ± standard errors.When the homogeneity of variance(P

> 0.05 on the Levene test) of the data indicated a normal distribution (P

> 0.05 on the Kolmogorov-Smirnov and Shapiro-Wilk tests), we used oneway analyses of variance (ANOVAs) to compare data among three groups and Student’st

-tests to compare data between two groups.Post hoc

tests for the one-way ANOVA (e.g.least significant difference and Bonferroni’spost hoc

tests) were applied for pairwise comparisons.Spearman correlation analysis was used to test for associations between variables.The significance level for all statistical tests was set atP

< 0.05.Results

Serum GDNF reduction is a risk factor for cognition dysfunction in PD

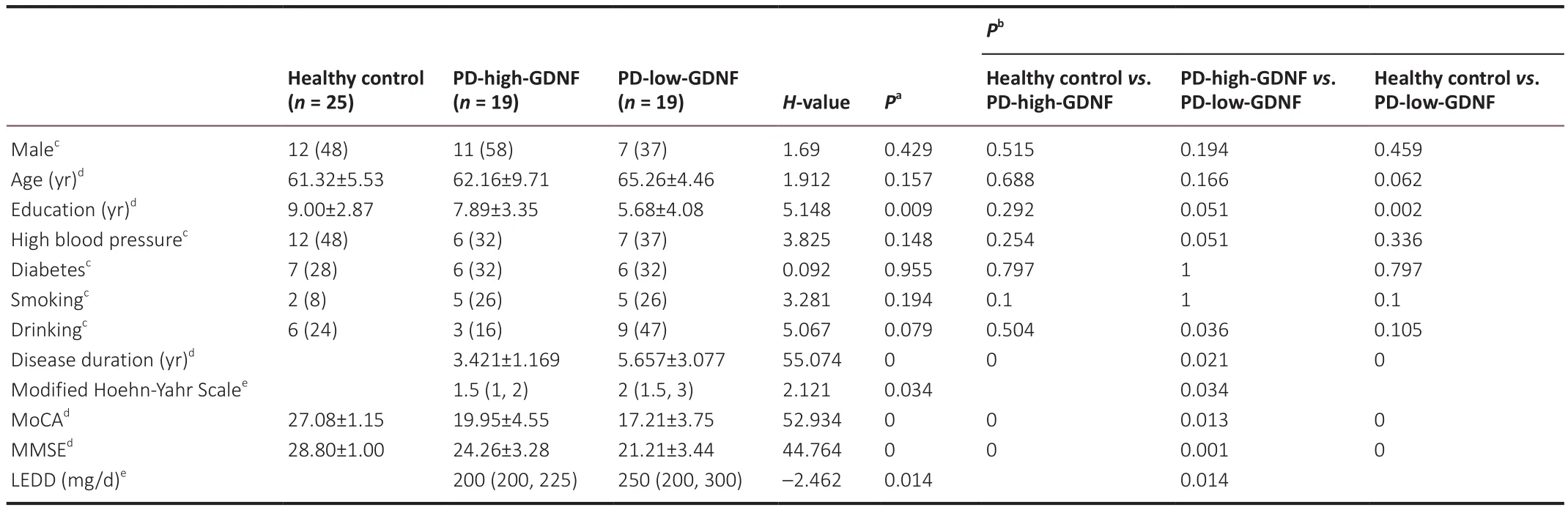

Thirty-eight patients with PD and 25 healthy controls provided blood samples and underwent complete evaluations.K-means clustering was used to divide the PD group into two subgroups according to serum GDNF levels: PD-high-GDNF and PD-low-GDNF groups (Additional Table 1 and Additional Figure 1).There were no significant differences in age, sex, diabetes mellitus,hypertension, smoking, or alcohol consumption between the subgroups (P

>0.05; Table 1).There were significant differences in education, disease duration,Hoehn-Yahr stage, cognitive score (MMSE, MOCA), and LEED among the three clusters (P

< 0.05; Table 1).The clinical trial process is shown in Figure 1B.

Figure 1| The procedure of the animal experiment (A) and the clinical trial (B).

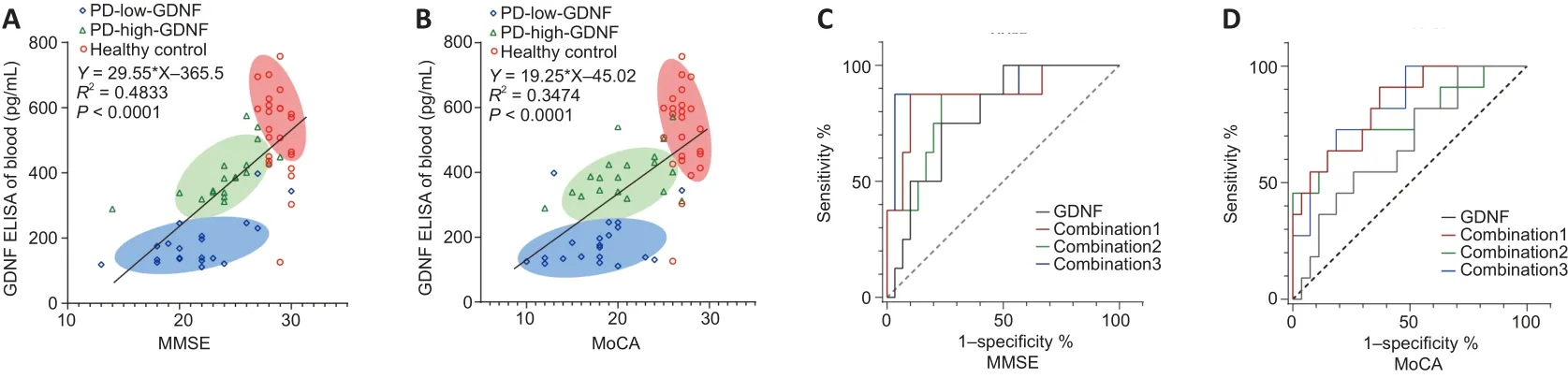

The correlation between the serum level of GDNF and MMSE and MoCA scores was examined using Pearson correlation.There was a significant positive correlation between the serum level of GDNF and cognitive score(R

= 0.695,P

< 0.001;R

= 0.659,P

< 0.001), as shown in the scatter plot with a fitted regression line in Figure 2.The PD group is presented separately, and partial correlation analysis was performed using multiple factors as covariables.The positive correlation between serum GDNF concentration and cognitive score was retained in the various adjusted covariate models (Additional Table 2).In the univariate logistic analysis, we identified PD as a risk factor for cognitive impairment regardless of whether cognitive function was evaluated using the MMSE (OR = 12.667, 95% confidence interval (CI): 4.276–37.524) or the MoCA (OR = 17.480, 95% CI: 4.514–67.690; Additional Table 3).Thus, we further analyzed whether a high serum GDNF level served as a protective factor for cognition in the PD subgroup.The univariate binary logistic regression analysis revealed that a high serum GDNF level decreased the risk and severity of cognition dysfunction for analyses based on both the MMSE (OR = 0.405, 95% CI: 0.228–0.720) and MoCA scores (OR = 0.562, 95%CI: 0.348–0.907; Additional Table 4).Furthermore, after adjusting for PD duration, Hoehn-Yahr stage, LEDD, and alcohol consumption, the OR value was maintained at < 1 (OR = 0.338 for the analysis using the MMSE score; OR= 0.498 for the analysis using the MoCA score), which indicated that a high GDNF level is a protective factor for cognition and a dependent factor for the diagnosis of cognitive dysfunction, although the 95% CI overlapped with the vertical line of no effect (line value = 1).

The ROC curve analysis (Figure 2C and D) results demonstrated that the serum GDNF level has diagnostic potential in discriminating mild and moderate cognitive impairment according to the MMSE score (area under the ROC curve [AUC] = 0.797, 95% CI 0.6400–0.0.9433,P

= 0.012), but not the MoCA score (AUC = 0.6667, 95% CI 0.4832–0.8501,P

= 0.1111).The combination of GDNF level, PD duration, Hoehn-Yahr stage, LEDD, alcohol consumption, sex,age, education, blood pressure, diabetes, and smoking provided the highest AUC among other factor combination models in the differentiation of degrees of cognitive impairment (Additional Table 5).Notably, risk estimation was calculated using the cutoff value (189.7 pg/L) determined by the optimal Youden index in the ROC curve analysis, which fell within the PD-low-GDNF clustering range.

Figure 2 | Linear correlation analysis and receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve analysis for predicting the degree of cognitive impairment.

Patients with insufficient GDNF exhibit greater executive dysfunction

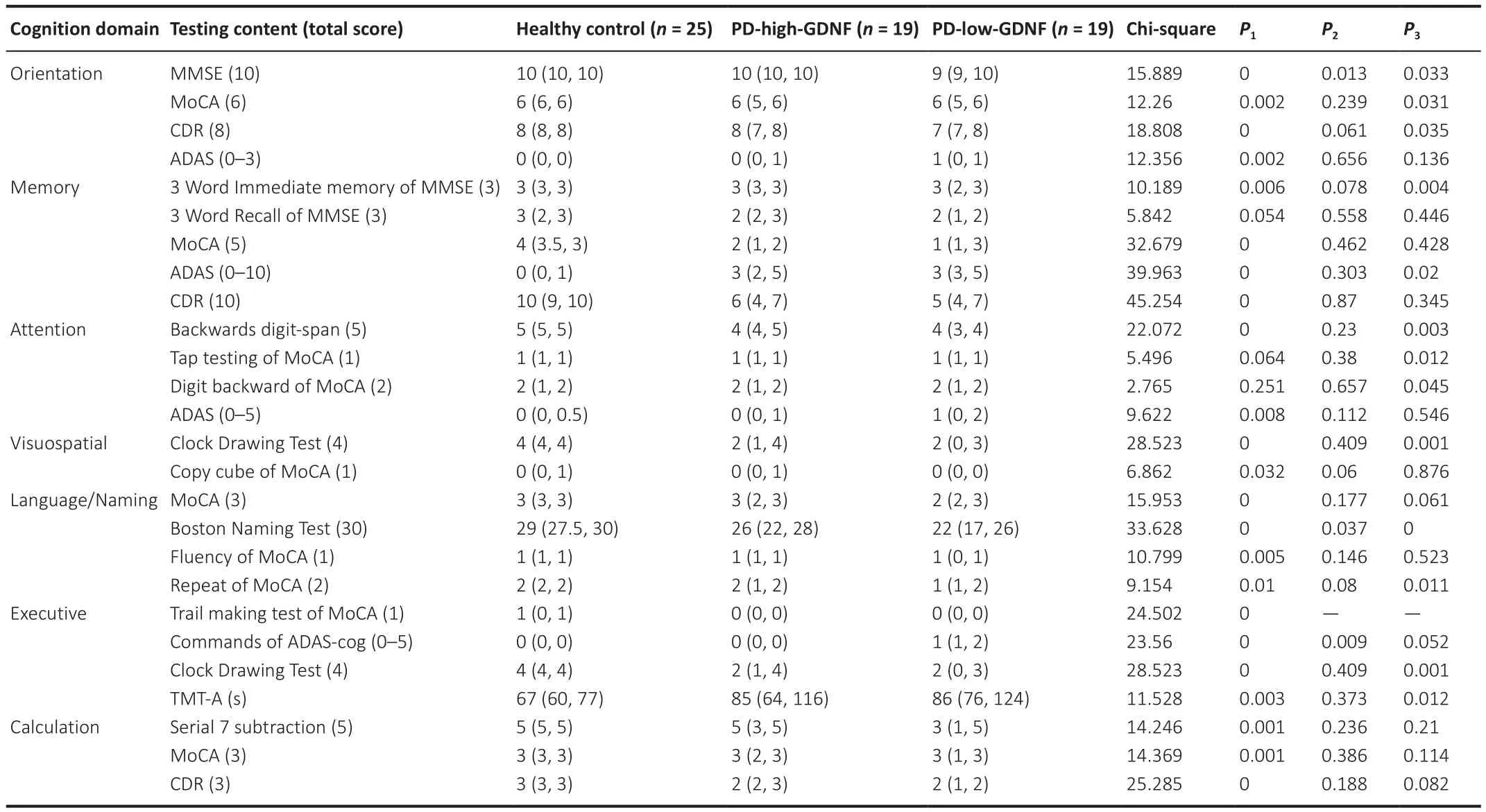

Next, we explored which cognitive domain is most affected by the reduction in serum GDNF.The cognitive assessment results were divided into the seven cognitive characteristics, which yielded three domains: executive function,attention, and visuospatial function.We accounted for cognition performance differences by adjusting for multiple covariates, especially for executive functions assessed in the Clock Drawing Test and TMT-A (Table 2).

Table 1 |Baseline demographic and clinical characteristics between PD patients and healthy control

Table 2 |Comparison of scores in different cognitive domains in different groups

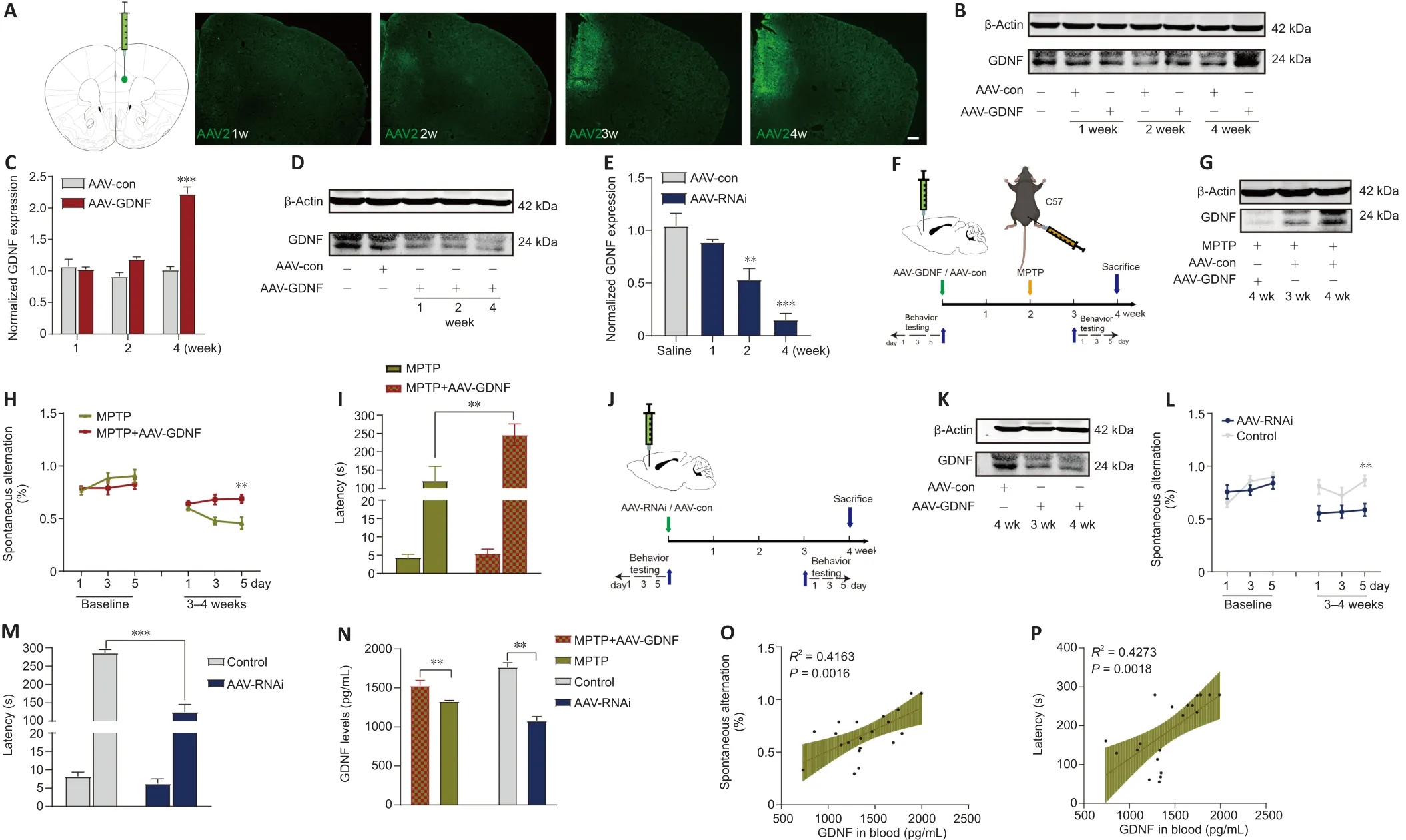

Deletion of PFC GDNF triggers cognition decline in mice via intrinsic mechanisms by which increased membrane DAT causes a reduction in effective DA transmission

To examine the correlation between the PFC and blood levels of GDNF in PD mice, we compared GDNF level changes after demonstrating that MPTP successfully induced the loss of DANs in the substantia nigra.Mice showed a deficit in working memory/avoidance memory performance as well as a GDNF reduction in both the PFC and serum.There was a significant positive correlation between decreased GDNF and cognitive dysfunction in mice(Additional Figure 2).To gain further insight into the effects of endogenous GDNF loss in the PFC on cognition, we used a unilateral stereotaxic injection to deliver AAV-mediated GDNF knockdown into the PFC of C57BL/6J mice (Figure 3A–P) and assess whether the reduction in the GDNF level impairs cognition,thereby mimicking the initial onset of PD.We examined the primordial extent of viral transfection in the PFC (Figure 3A) and found that AAV-GDNF-RNAi(AAV-RNAi) specifically reduced GDNF levels in the PFC (Figure 3D, E, and K).Short-term spatial working memory was altered in AAV-RNAi-treated mice,reflected by their similar spontaneous alternation behavior during the Y-maze task to control mice (Figure 3L and M).In the passive avoidance reproduction memory test, AAV-RNAi-treated mice tended not to spend a prolonged period in the light compartment (Figure 3M).These clinical results suggested that the serum GDNF level is positively associated with cognitive performance(Figure 3N–P).

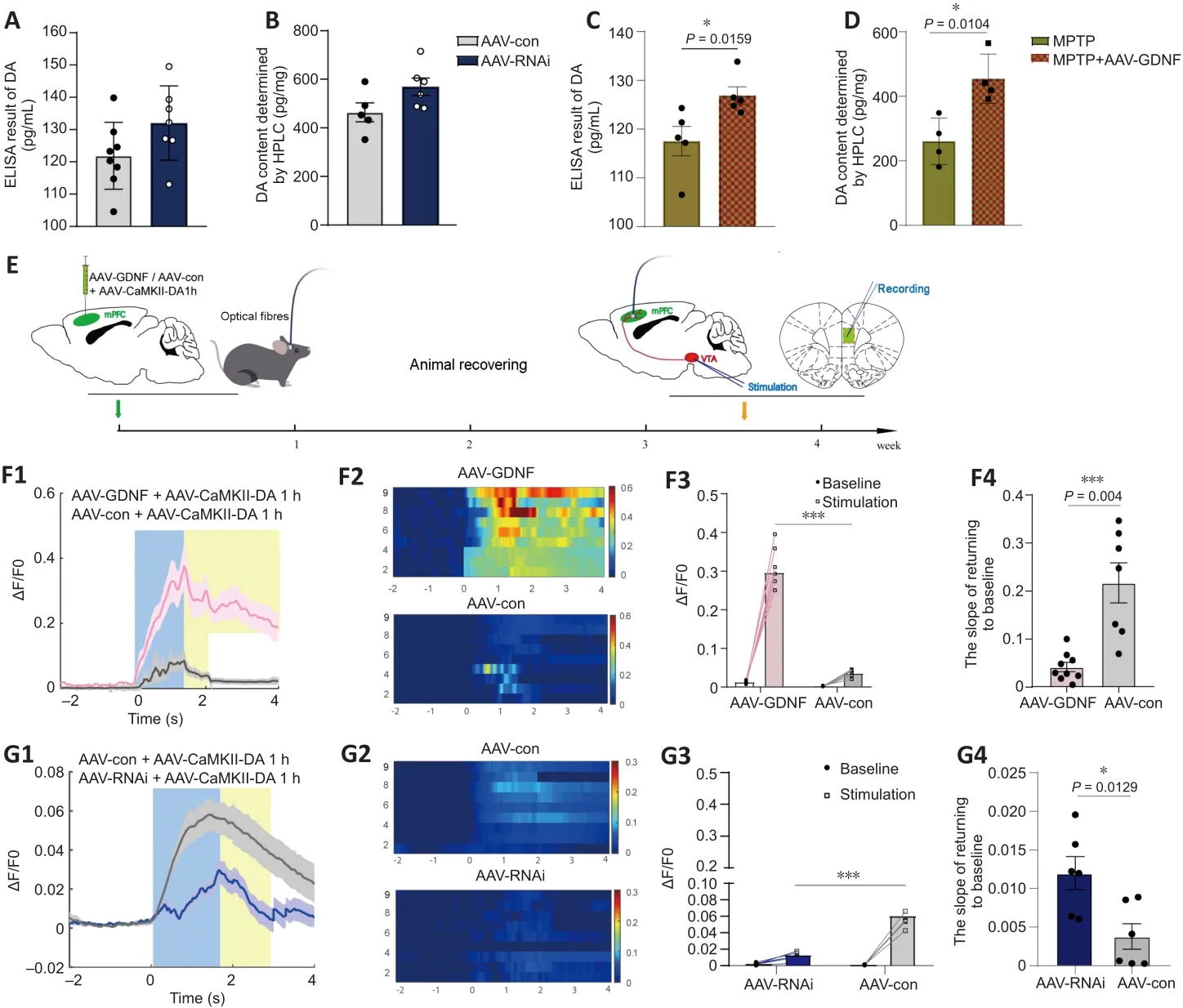

The ELISA and HPLC analyses for DA did not reveal any differences in DA level between the AAV-RNAi and AAV-con groups (Figure 4A and B).However,GDNF enhanced the level of DA in the PFC of MPTP mice (Figure 4C and D).To monitor changes in effective DA transmission, we virally expressed a high sensitivity and fast temporal resolution DA1h by administering AAV2-CaMKIIa-DA1h into the PFC of mice to examine PFC DA dynamics in the VTA projectionin vivo

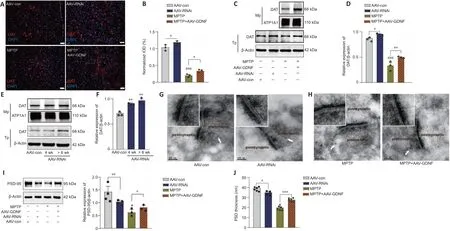

.Electrical stimulation of the VTA elicited transient fluorescence increases in the PFC (Sun et al., 2018; Figure 4E).In all mice,VTA stimulation triggered a corresponding change in the fluorescence signals in the PFC.Furthermore, the averaged DA1h fluorescence in the AAV-GDNF group increased significantly more than in the AAV-con group (Figure 4F).Moreover, this group exhibited a prolonged decay of signals to baseline (> 4 seconds), as reflected by the size of the slope (Figure 4F), whereas the signals of the control group returned to baseline rapidly in approximately 2 seconds.In contrast, the DA1h signal of the AAV-RNAi group peaked at the end of the 1.7-second stimulation and sharply decreased to the pre-stimulation level in 3 seconds (Figure 4G).Furthermore, the slope of the signal returning to the pre-stimulation level in the AAV-RNAi group was higher than that in the AAV-con group (Figure 4G).Overall, the fluorescence signals in the AAV-RNAi group were lower than those in the control and AAV-GDNF groups (Figure 4G).However, because of the regulation effect of GDNF on DAT, the levels of DA in the synaptic cleft were not consistent, which contributed to the differences in the DA1h signal value and the signal decay time.We found a significant increase in DAT levels in the AAV-RNAi group, and the enrichment of DAT in the membrane was most evident in this group (Figure 5A–F).Notably,when we assessed the structure of dopaminergic synapses in the PFC in more detail via immune electron microscopy, there was insufficient evidence to indicate significant DAT level changes in the dopaminergic presynaptic components.However, the thickness and volume of the postsynaptic dense area showed slight variations, which appeared as thinning in the AAV-RNAi group (Figure 5G).Furthermore, the synaptic marker PSD95 was decreased,which corresponded to the elevated DAT in the AAV-RNAi group (Figure 5C and I).These results indicated that GDNF deficit-induced DAT enrichment involves reductions in effective DA transmission and dopaminergic synapse modification.Altered excitatory field potentials and spine remodeling in the PFC following alterations in GDNF mediate the change in DA transmission

Both GDNF and DA signaling modulate synaptic plasticity (Chen et al., 2008;Kopra et al., 2017).However, the plasticity of excitatory glutamatergic neurons is rarely reported, especially in the PFC.The above observations prompted us to test whether a decrease in GDNF results in a reduction in LTP (Figure 6A–F).We found that the AAV-RNAi group had a greater deficit in LTP than the AAV-con group (Figure 6B).To test whether an increase in DA concentration ameliorates this LTP deficit in AAV-RNAi mice, we added DA into the ACSF and acquired electrophysiological recordings.Appropriate DA supplementation ultimately rescued LTP in the GDNF-deficit mice (Figure 6C).As shown in Additional Figure 3, the fEPSP amplitude was significantly increased by lowdose DA (< 250 nM) and was significantly decreased once high-dose DA was administered (> 250 nM).

Figure 3 | Glial cell line-derived neurotrophic factor (GDNF) reverses cognitive deficits induced by MPTP, and a decrease in GDNF level in the prefrontal cortex (PFC) directly leads to cognitive impairment.

Figure 4|Effect of glial cell line-derived neurotrophic factor (GDNF) on the release and reuptake of endogenous dopamine (DA) measured in the prefrontal cortex (PFC).

Differences in the change in expression of the synaptic marker PSD95 (Figure 5I and J), according to the above results and LTP (Figure 6A–F), suggested that the change is associated with spine density (Figure 6H–K).The dendritic spines were abundant and uniformly distributed (Figure 6J), the boundary of spines was clear, and the morphology was predominantly mushroom-shaped,long, and thin.The AAV-RNAi-treated mice showed a marked reduction in spine density in the PFC (Figure 6J and K).In addition, the dendrites became swollen, and the boundary of the spines became blurred.Notably, we observed that the structure of the dendritic tree of the pyramidal neurons tended to exhibit fewer intersections, and only the apical dendrites with relatively distinct features were retained in AAV-RNAi mice, as observed in the Sholl analysis (Bird and Cuntz, 2019; Figure 6H and I).

GDNF ameliorates cognitive deficits and behavioral abnormalities by restoring the deficit of dopaminergic axons in the PFC of PD mice

Numerous studies have demonstrated that GDNF induces behavioral recovery in PD patients and animal models of PD (Kordower et al., 2000; Chen et al.,2008).Typical cognitive behaviors for control and MPTP-treated mice are illustrated in Additional Figure 2A.The effectiveness of MPTP lesions was demonstrated by comparing the tyrosine hydroxylase (TH)cells in the VTA and the substantia nigra between PD and sham mice (Additional Figure 2B).Saline-treated mice showed clear shock stimulation memory during the passive avoidance task.However, in PD mice, MPTP impaired passive avoidance memory retention during the step-through tasks (Additional Figure 2F) and spontaneous alternations during the Y-maze task (Additional Figure 2C).AAV-GDNF was administered 2 weeks before modeling MPTP(Figure 3F).The pre-injection of AAV-GDNF markedly reversed MPTP-induced avoidance memory retention impairments in MPTP + GDNF group, which was not observed in the MPTP group (Figure 3I).Similarly, for the evaluation of working memory performance, the MPTP-treated mice exhibited a significant decrease in the percentage of correct alternations during the Y-maze test(Figure 3H).

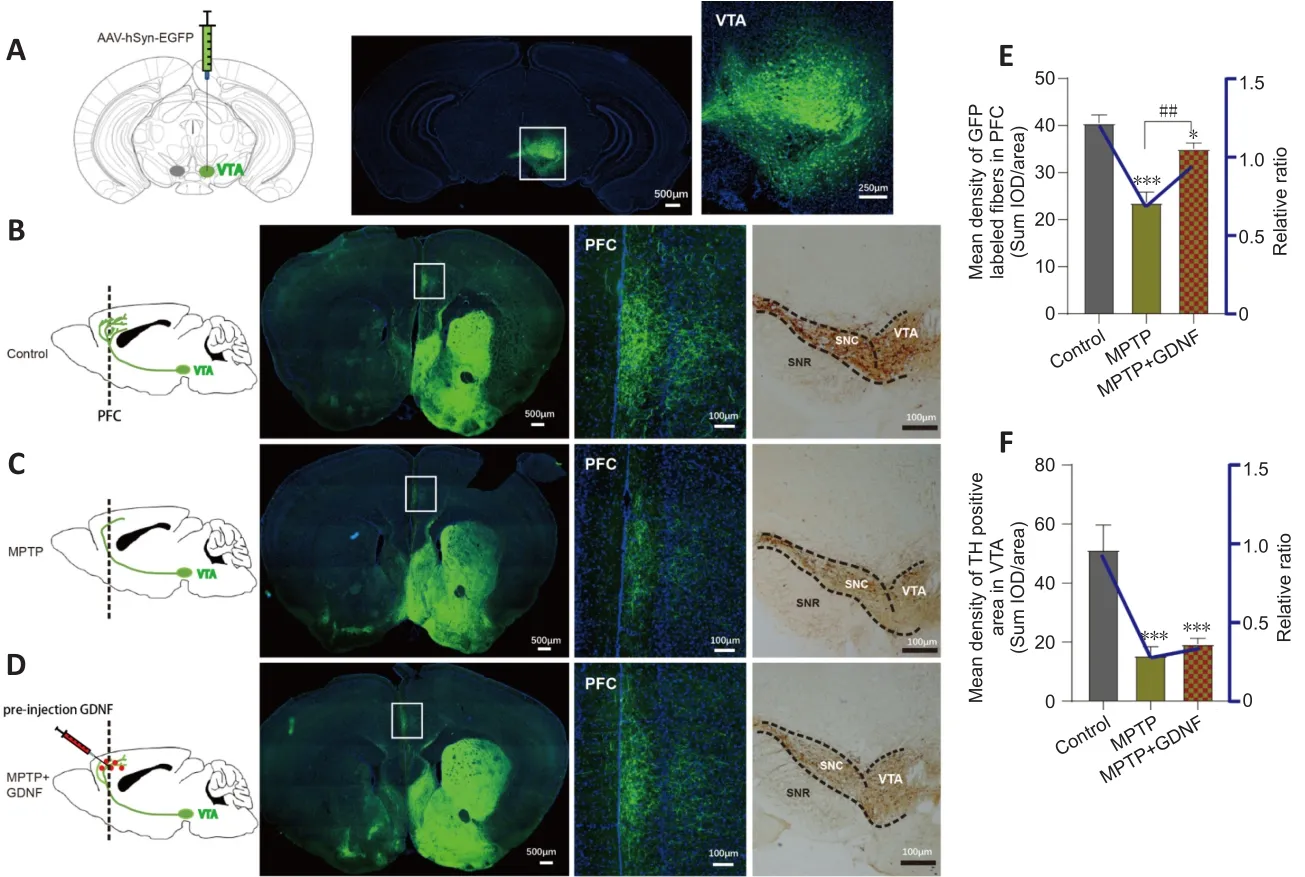

We speculated that there were changes in the dopaminergic transmission in the PFC.First, the ELISA and HPLC assays demonstrated that the DA concentration in the PFC was significantly decreased (Figure 4C and D).Furthermore, we used DA dynamics recordings to detect electrically-evoked DA release in the PFC to examine how MPTP affects DA output in the PFC.We found a significant decrease in the peak amplitude of evoked extracellular DA released in MPTP mice (Additional Figure 4A–C).Significantly more DA was released following the same stimulation when there was sufficient GDNF,and DA had a longer-lasting effect (Additional Figure 4D).Furthermore, we administered an anterograde AAV-syn-enhanced green fluorescent protein(EGFP) injection into the VTA and observed a decrease in dopaminergic fibers in the PFC of PD mice (Figure 7A–C).However, when the GDNF factors were injected early, the PFC received more EGFP-positive fibers (Figure 7D–F);thus, the diminished dopaminergic innervation was reversed.With the loss of dopaminergic fibers, western blotting (Figure 5A–D) and the HPLC assay(Figure 4C and D) showed that the DAT and DA levels were inevitably reduced,which also explains the reduction in DA delivery.It is well-established that the loss of dopaminergic projections profoundly affects cognitive flexibility, which is consistent with our behavioral results.

Elevation of GDNF levels in PD mice relieves spine loss and long-term synaptic plasticity deficits

DA can individually or cooperatively affect long-term synaptic plasticity in the PFC (Goto et al., 2010; Xing et al., 2016).The immunoelectron microscopy assay revealed that DA loss induced by the administration of MPTP significantly decreased the postsynaptic density (PSD) thickness of the postsynaptic element of the dopaminergic synapse (Figure 5H–J).The total PSD95 level in the PFC region also showed a decline (Figure 5I).Moreover,the AAV-GDNF group showed a greater increase in PSD thickness of the dopaminergic synapse and the PSD95 level of the PFC than the MPTP- induced mice (Figure 5H–J).When we evaluated the synaptic plasticity of the PFC, the MPTP-treated mice exhibited a pronounced reduction in the fEPSP amplitude(Figure 6D), which may account for their working memory deficits.These deficits were partially restored by pre-treatment with AAV-GDNF (Figure 6D)or exogenous DA supplementation (Figure 6E), which suggested that GDNF plays a crucial role in regulating the function of dopaminergic synapses.Given the chronically low DA, we then investigated the changes in dendritic length and distribution of glutamatergic neurons in the PFC levels and conducted spine analysis.Notably, we visually detected varying degrees of branch-likedendrite network loss in the MPTP-induced mice.Sholl analysis identified a distinctive loss of dendritic branches in the radiation range centering on the neuron body in the MPTP mice (Figure 6H and I).

Figure 5| Effect of glial cell line-derived neurotrophic factor (GDNF) on dopamine transporter (DAT), postsynaptic density protein 95 (PSD95) expression, and dopaminergic synaptic morphological structure.

Additionally, we observed a significant reduction in the number of dendritic spines in the PFC after administering MPTP.Shrinkage of the spine heads and morphological changes in the spine were also observed (Figure 6J–K).Interestingly, GDNF promoted spine formation and stability and enabled the generation of farther-reaching connections with axon terminals and higher dendritic spines density (Figure 6H).LTP is a neurophysiological process that depends on neuronal activity and reflects synaptic plasticity and synaptic connection strength.This plasticity enables the nervous system to adapt to changes in the environment (sensory information) and behavior and contributes to inhibitory control and cognitive flexibility, which are the primary components of executive function (Feldman, 2009).We found that 100 Hz HFS could not induce LTP in the PFC slices (Figure 6D).To further test whether GDNF elevation is sufficient to facilitate LTP induction in the PFC pyramidal cells in the MPTP group, mice were pretreated with AAV-GDNF (i.e., MPTP +AAV-GDNF group).Sufficient GDNF ensured that LTP was maintained in the PFC(Figure 6D) and improved PFC intrinsic excitability.Similar to supplementation with exogenous DA, the fEPSPs were intact after applying the same HFS stimulation to the PFC (Figure 6E).Taken together, the impact of exogenous DA equals that of GDNF protection in MPTP-induced mouse PFC slices; GDNF works by regulating dopaminergic synapses and altering LTP in the PFC.

Functional connectivity of the PFC changes according to DC

The voxel-wise DC analysis based on graph theory using the functional MRI data showed DC abnormalities in mainly the neocortex, hypothalamus, and medulla in all groups (Additional Figure 5A).Compared with the control group, the PFC GDNF-deficit group showed lower DC in the neocortex,whereas the hypothalamus showed significantly higher DC (Additional Figure 5B).The neocortex showed a trend lower DC in the MPTP group compared with the control group, the difference was not significant.Furthermore,supplementary GDNF induced a trend greater restoration in DC of the three nodes compared with the MPTP group but the differences were not significant in the neocortex or medulla.Collectively, we speculated that longterm loss of GDNF in the medial prefrontal lobe reduces network connectivity in the neocortex and simultaneously increases abnormal connectivity in the hypothalamus.In the MPTP-induced group, adequate GDNF could reverse the change in DC, which would contribute to the restoration of connectivity of the neural network.

Figure 6 | Glial cell line-derived neurotrophic factor (GDNF) altered long-term potentiation (LTP), mediated by dopamine (DA) level, dendritic spine density, and morphology of the prefrontal cortex (PFC).

Figure 7|Glial cell line-derived neurotrophic factor (GDNF)decreases the loss of dopaminergic axons from the ventral tegmental area (VTA) in the prefrontal cortex (PFC).

Discussion

The main finding in the present work was that decreased GDNF in the PFC triggered deficits in dopaminergic synaptic transmission, such as the degeneration of dopaminergic synaptic function, which may contribute to cognitive impairment in patients with PD.

GDNF is considered a protective factor of DANs (Mu et al., 2020).It is derived from not only glial cells (e.g., astrocytes and microglia) (Batchelor et al.,1999; Chen et al., 2006) but also neurons (DANs and parvalbumin-positive interneurons) (Pochon et al., 1997; Hidalgo-Figueroa et al., 2012); moreover,it achieves balance in the brain via retrograde axoplasmic transport (Wang et al., 2010).GDNF is widely distributed in the brain, including the striatum,cortex, hippocampus, spinal cord, and PFC, the latter of which is a core region for advanced cognitive function (Mitra et al., 2021).Several studies have focused on the role of GDNF in the mesocorticolimbic DA system (e.g.,the PFC, VTA, and nucleus accumbens) (Li et al., 2013; Koskela et al., 2021);however, none of these studies investigated the impact of GDNF in the PFC on cognition in PD.

An observational study showed lower serum GDNF levels in PD patients than in the control population, which is consistent with the findings of our previous work (Liu et al., 2020).Several studies to date have identified a link between GDNF and cognition in diseases other than PD.GDNF levels are lower in patients with postoperative cognitive impairment than in those without cognitive dysfunction (Duan et al., 2018).Furthermore, a recent study found a correlation between serum GDNF level and cognition in obsessive-compulsive disorder mice, where lower GDNF levels were associated with impaired cognitive behavior (Guo et al., 2020).Similarly, after adjusting for PD duration,Hoehn-Yahr stage, and LEDD, we found that GDNF serum levels were strongly positively correlated to MMSE and MoCA scores, which suggested that low serum GDNF levels are a sign of cognitive impairment in patients with PD.

Given that serum GDNF concentrations are positively correlated with cerebrospinal fluid GDNF levels (Straten et al., 2009), the decreased serum GDNF level observed in our study implies a GDNF deficiency in the brain.Our animal experimental data confirmed that the subacute MPTP mouse model of PD had reduced GDNF in the PFC due to the effect of MPTP on the ability of astrocytes to synthesize and release GDNF (Gao et al., 2021).In contrast, PD mice with high GDNF levels in the PFC showed an improvement in cognitive performance.

Neuromodulators such as DA, norepinephrine, serotonin, and acetylcholine are the primary regulators of neuronal electrical activity and subsequent outward output to the PFC subcortical area (Lohani et al., 2019).DA is thought to play pivotal roles in diverse cognitive-behavioral functions by precisely modulating PFC activity (Miller and Cohen, 2001).Our DA dynamics recording analysis results showed that GDNF boosts DA fluorescence and reduces signal decay after electrical stimulation of the VTA.In contrast, DA concentrations were considerably lower in MPTP-induced animals because of pathological changes, such as DAN death, a lack of DA synthesis, and decreased DA storage(Goldberg et al., 2011).Thus, GDNF may prevent DA loss.We hypothesized that lowering GDNF levels primarily affects extracellular DA levels rather than the presynaptic storage of DA.However, GDNF also influences the spontaneous firing of VTA DA neurons (Wang et al., 2010), which is an important component of the neuronal circuitry underlying cognition given its role as a retrograde enhancer of dopaminergic tone in the mesocorticolimbic system (Nicola, 2007).Therefore, the contribution of GDNF loss in the PFC to cognitive decline may be a possible explanation for diminished DA transmission, although further evidence is required.Ourin vivo

DA dynamics study showed that the DA1h signal of the AAV-RNAi group peaked sharply and decreased to pre-stimulation levels in 1 second, whereas that of the AAVGDNF group showed a significantly higher peak than the AAV-con group,followed by a long-lasting reduction (i.e., > 2 seconds), indicating that fewer DAT surface expressions occur during the adaptive response.The results of western blot assay showed that the membrane expression of DAT wasenhanced when the baseline GDNF was downregulated, which is consistent with the findings of Boger et al.(2007).This may explain our findings in the PFC.Moreover, Barroso-Chinea et al.(2016) discovered that long-term GDNF overexpression reduces DAT activity.Similarly, this phenomenon was also observed in the striatum in the dopaminergic projection of the terminal region (Barroso-Chinea et al., 2005).Indeed, several studies have demonstrated that protein kinase C (PKC) signal-induced internalization of the transporter regulates the surface expression of DAT (Sorkina et al., 2005),which offers new avenues for elucidating the regulation mechanism of GDNF to DAT internalization.The ELISA and HPLC assays revealed no significant differences in DA level between GDNF loss and control conditions under healthy settings.We only observed a significant difference in the DA dynamics analysis.GDNF has been shown to increase DA release by blocking A-type potassium channels, which results in presynaptic membrane depolarization and calcium entry (Yang et al., 2001).Therefore, we postulated that decreasing dopaminergic terminal GDNF (in the PFC) would encourage the development of membrane DAT expression, improve reuptake ability, and diminish terminal release, all of which contribute to reduced DA transmission.We showed that GDNF restored axonal ends and reduced MPTP toxin-induced DAN bodies, which indicated that the number of DATs in the DA storage at the terminal was maintained.

Two studies have demonstrated that when PSD95, which is closely related to DA transmission (Rubino et al., 2009b), is lowered in the PFC, rats exhibit impaired spatial working memory because of a lack of synaptic efficiency and hypoactive synapses (Rubino et al., 2009a).Our Golgi staining analysis showed that when DA transmission was reduced, there was less dendritic branching complexity in the pyramidal neurons, which formed a “micro-network” with limited intersections.Moreover, there was a reduction in spine density.In addition, in the GDNF-RNAi group, the number of protruding dendritic spines increased, and the spines became shorter and coarser.The expansion of these stubby and wide dendritic spines does not affect synaptic connections,although their excitatory transmission function is reduced (Danglot et al.,2012), which indicates the degeneration of dendritic spines.Similar decreases in spine density and morphological abnormalities were discovered in MPTP-induced mice.The proportion of these architectural changes and the number of new/eliminated spines may be associated with memory formation and information flow pathways (Yang et al., 2009).When combined with the LTP findings, these spine alterations may be specifically linked to pyramidal neuronal excitability and effective information processing.It has been shown that DA levels in the PFC must be appropriately maintained to sustain adequate synaptic plasticity and enable proper cognitive function (Tang et al., 2019a), which is consistent with our findings.Our examination of changes in DC using imaging showed a drop in DC value in the neocortex following GDNF knockdown, which indicated a decrease in prefrontal connectivity.However, because of our small sample size, it is difficult to provide a detailed interpretation.Nevertheless, we highlight one possibility of long-term projection association alterations, which result in cognitive impairment.

In summary, during the early stages of PD, non-motor symptoms, especially cognitive impairment, may occur with relatively minimal alterations to dopaminergic terminals (in the PFC) caused by GDNF deficiency, which weakens DA transmission, pyramidal neuronal activity, and the connectivity of the PFC to other regions.

Acknowledgments:

We would like to thank all members of the Neurobiology Laboratory of Xuzhou Medical University past and present who participated in this project.In particular, we thank Di Wang from Anesthesiology Laboratory of Xuzhou Medical University, and Peng-Lai Liu from Biochemistry Experimental Center of Xuzhou Medical University for technical input and data mapping.

Author contributions:

Study design and conception: CXT, DSG; animal experiment implementation and data collection: KQS, XYZ, CCM, YHL, MTL,JC, CXT; clinical peripheral blood samples collection and cognitive evaluation:MYS, YFL, WX, GC, JW, XL; data analysis: XYZ, CCM, MYS; manuscript draft:CXT, JC; manuscript review: PAK, WW, AAA.All authors approved the final version of the manuscript.

Conflicts of interest:

All authors declare they have no competing interests.

Availability of data and materials:

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article and its supplementary information files.

Open access statement:

This is an open access journal, and articles are distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons AttributionNonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 License, which allows others to remix, tweak, and build upon the work non-commercially, as long as appropriate credit is given and the new creations are licensed under the identical terms.

Open peer reviewers:

Xavier d’Anglemont de Tassigny, Instituto de Biomedicina de Sevilla, Spain; Leonardo Cocito, Universita degli Studi di Genova, Italy;Guoping Peng, the First Hospital of Zhejiang Province, China.

Additional files:

K-means clustering analysis (A) and the violin plot of GDNF serum level based on K-means grouping (B).

The correlation of GDNF level between the medial prefrontal cortex and the peripheral blood was verified in the model of PD with

cognitive impairment.

LTP induction in the PFC was regulated by DA level, and the U-shaped relationship between prefrontal dopamine level and fEPSP amplitude.

Effect of GDNF on release and reuptake of endogenous DA in PFC based on MPTP-induced mice.

Differences in degree centrality of different groups mice in the in the resting state.

Comparison of serum GDNF level in three groups based on k-means clustering.

Correlation analysis between serum GDNF and cognitive score.

ORs (95% CIs) for cognition disorder and PD.

ORs (95% CIs) for Parkinson’s disease with cognition disorder and serum GDNF level.

The diagnosis efficiency of the ROC analysis of serum GDNF.

Hospital ethic approval (Chinese).

STROBE checklist.

Open peer review reports 1–3.

- 中国神经再生研究(英文版)的其它文章

- The effects and potential of microglial polarization and crosstalk with other cells of the central nervous system in the treatment of Alzheimer’s disease

- Novel therapeutic strategies targeting mitochondria as a gateway in neurodegeneration

- Vimentin as a potential target for diverse nervous system diseases

- Clemastine in remyelination and protection of neurons and skeletal muscle after spinal cord injury

- Artificial nerve graft constructed by coculture of activated Schwann cells and human hair keratin for repair of peripheral nerve defects

- The critical role of the endolysosomal system in cerebral ischemia