Expression of the methylcytosine dioxygenase ten-eleven translocation-2 and connexin 43 in inflammatory bowel disease and colorectal cancer

Mohammad E-Harakeh, Jessica Saliba, Kawthar Sharaf Aldeen, May Haidar, Layal El Hajjiar,Mireille KallassyAwad,Jana G Hashash,Margret Shirinian,Marwan El-Sabban

Abstract

Key Words: Demethylation; Inflammation-induced carcinogenesis; Ulcerative colitis; Colorectal cancer;Connexins

INTRODUCTION

The gastrointestinal tract is constantly exposed to environmental insults that may potentially lead to pathologies. Inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) is a relapsing and remitting inflammatory disorder affecting distinct parts of the gastrointestinal tract. It comprises two primarily encountered disorders:Crohn’s disease and ulcerative colitis, which can be distinguished by their localization in the different parts of the gut and the endoscopic appearance of the inflamed segment[1-3]. IBD increases the risk of developing colon adenocarcinoma[4], and colitis-associated colon adenocarcinoma remains a fundamental consequence of sustained IBD, possibly because both IBD and colon adenocarcinoma share etiological factors implicated in their development[5].

Gap junctions (GJs), components of junctional complexes, have a potential role in regulating epithelial integrity and function. GJs are formed by the docking of two hemichannels (connexin hexamers)contributed from two adjacent cells, allowing the direct exchange of ions and small signaling molecules(< 2 kDa)[6]. Connexins play a pivotal role in cellular proliferation, differentiation, and function and are recognized as putative tumor-suppressor genes[7-9]. The library of connexin-related diseases has been emerging for many years, and includes various types of syndromes and disorders, such as inflammatory diseases and cancer. Several studies have revealed that the inflammatory response relies in part on connexins and GJ-mediated intercellular communication (GJIC)[10]. More specifically, alteration in the expression of connexin 43 (Cx43) in the gastrointestinal tract is associated with IBD, gastrointestinal infections, and impaired motility[11,12]. We have previously shown an alteration of Cx43 expression and localization, as well as a direct heterocellular communication between intestinal epithelial cells(IECs) and macrophages, which may contribute to IBD pathogenesis[12].

In complex diseases, such as IBD and colon adenocarcinoma, in addition to the heritable component,environmental and epigenetic (DNA methylation and demethylation, histone marks, higher order chromatin structure,etc.) factors are likely to influence onset[13]. DNA methylation state is controlled by the interplay between DNA methyltransferases and demethylating enzymes, such as ten-eleven translocation (TET) proteins. Methylation occurs at normally demethylated CpG-rich regions named “CpG islands”, of which 70% overlap with human gene promoters, and results in gene silencing[14]. DNA methylation profiles from IBD patients are considerably altered compared to healthy counterparts[15].Moreover, in IBD-associated colon adenocarcinoma, DNA methylation status was distinct from sporadic colon adenocarcinoma, with different gene expression profiles[16]. DNA methylation is counteracted by demethylation mechanisms, catalyzed by TET enzymes (TET-1, TET-2, TET-3), thus activating gene transcription[17]. Following a series of oxidation reactions by TET enzymes, previously methylated 5-methylcytosine is converted to 5-hydroxymethylcytosine (5-hmC) and further oxidized products that will be recognized and excised by thymine-DNA glycosylase/base enzyme repair pathway to result in an unmethylated cytosine residue[18]. TET genes are mutated in a variety of diseases and cancers. In inflammatory diseases, TET-2 is crucial for the repression of the pro-inflammatory cytokine, interleukin(IL)-6[19], while in several cancers, TET-2 expression is downregulated[20]. In particular, tumors of the digestive tract express different levels of TET enzymes, which are explored as potential factors informing prognosis[21]. Downregulation of TET-1, TET-2, and TET-3 have been reported in gastric cancers with concomitant loss of 5-hmC marks[22]and in colorectal carcinoma[23], with TET-2 transcriptional levels potentially serving as indicators for treatment outcome and disease recurrence[23]. In addition, a recent study reported that the human gene coding for TET-2 contains three promoter elements which are differently regulated in different tissues and developmental stages[24]and may play a role in cancer development.

While many studies have reported the Cx43 promoter to be hypermethylated during the transition from inflammation to cancer[25-27], the expression statuses of Cx43 and TET-2 in IBD and colorectal cancer have not been simultaneously described. This study investigated the effect of inflammation and Cx43 expression levels on the intestinal cell membrane integrity and described TET-2 expression and 5-hmC marks under inflammatory statesin vitro, in vivo, and in human samples of ulcerative colitis and sporadic colon carcinoma.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Cell lines and culture conditions

The HT-29 and Caco-2 cell lines derived from colorectal adenocarcinoma tissues were used as models for human IECs. When grown in monolayer, these cells become more differentiated and IEC-like[12,28,29]and are widely used as a model of intestinal transport and pathology, including inflammation.Human embryonic kidney cells (packaging HEK 293T cells) were used for production of viral supernatant for transduction purposes.

In addition, the human monocytic cell line (THP-1) was used as anin vitromodel for activated macrophages[12,30,31]for the production of conditioned inflammatory medium. After exposure to phorbol myristate acetate (PMA) and lipopolysaccharide (LPS), THP-1 cells become activated; they adhere to the cell culture vessel and show increased transcriptional levels of connexins, Toll-Like Receptor (TLR)-2, TLR-4, NF-κB p65, COX-2, inflammatory cytokines tumor necrosis factor-α (TNF-α),and IL-1β[12]. In this study, suspension THP-1 cells were activated with 50 ng/mL PMA (Sigma-Aldrich, St Louis, MO, United States) for 24 h, followed with 1 μg/mL of LPS (Sigma-Aldrich) for 4 additional hours. When activated THP-1 cells adhered to the cell culture plate, they were washed with PMA- and LPS-free media and left to grow for 72 h. Conditioned media was then collected, filtered, and appliedin vitroonto colon cell lines to create an inflammatory milieu.

Cells were maintained in complete RPMI-1640 (Sigma-Aldrich) for HT-29 and THP-1 cells or Dulbecco's Modified Eagle's medium (DMEM AQ; Sigma-Aldrich) for HEK 293T cells supplemented with 10% FBS (Sigma-Aldrich), 100 U/mL penicillin G, and 100 μg/mL streptomycin (Sigma-Aldrich).Cells were grown at 37 °C in a humidified incubator with 5% CO2atmosphere.

Generation of HT-29 cells upregulating Cx43 gene

The Cx43-pDendra2N construct (Evrogen, Moscow, Russia) was previously cloned into pCSCW lentiviral vectors[12]. The plasmid was then used to transform DH5α competentEscherichia colibacteria,which were then left to proliferate. Plasmid was then isolated and purified using the EndoFree Maxi plasmid purification kit (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany) to be used for transfection along with other plasmids (gag/pol/env) into HEK 293T cells for production of viral supernatant, which carries the Cx43-pDendra2 chimeric proteins. The viral supernatant was used to transduce HT-29 cells. Following the transduction, HT-29 cells were cultured, expanded, and highly positive cells (referred to as HT-29 Cx43D cells thereafter) were sorted using the BD FACSAria™ III sorter (BD Biosciences, Franklin Lakes,NJ, United States). Viral supernatants were obtained from HEK 293T cells and used to transduce HT-29 cells. These cells, named HT-29 Cx43D, were then isolated using a BD Fluorescence-Activated Cell Sorting Aria SORP cell sorter in the single-cell mode. Green fluorescence in HT-29 Cx43D cells attests to the successful upregulation of exogenous Cx43 in these cells.

Generation of HT-29 cells downregulating Cx43 gene using CRISPR/Cas9 system

HT-29 cells knocking down Cx43, referred to as HT-29 Cx43-cells, were generated using the CRISPR/Cas9 gene-editing system. After cloning the Cx43 target sequence (20 bp) into the guide RNA scaffold of the pX330-CRISPR plasmid, the bacterial transformation was performed as above and 10-15 colonies were picked to check for the correct insertion of the guide RNA by sequencing. Transfection of HT-29 cells with positive clones was performed, and cells were selected with puromycin (1 μg/mL)until isolated colonies were obtained. Several positive clones were validated for Cx43 knockdown at the RNA and protein levels. One specific clone resulted in more than 90% down-regulation of Cx43 mRNA,generating the experimental HT-29 Cx43-cells. This downregulation was confirmed by western blot and immunofluorescence assays.

Cell growth assay

Parental HT-29, HT-29 Cx43D, and HT-29 Cx43-cells were seeded in 24-well plates at a density of 25000 cells/cm2. At 24 h, 48 h, and 72 h, cells were washed with PBS and trypsinized. Viable cells were counted using the trypan blue exclusion dye.

Evaluation of barrier integrity

Trans-epithelial electrical resistance: This method evaluates barrier integrity of epithelial cells grown in monolayer; by describing the impedance of barrier-forming cell cultures. Briefly, electrodes are placed on both sides of the cellular barrier and an electric current is applied. The resulting current established in the circuit is measured and trans-epithelial electrical resistance (TEER) is calculated. The higher the TEER, the better the membrane integrity[32]. In this study, HT-29, HT-29 Cx43D, and HT-29 Cx43-cells were cultured on Transwell®inserts with 0.4 μm-pore size filters (Corning, Corning, NY,United States). TEER was measured on confluent cells in the presence or absence of 2% dextran sulfate sodium (DSS) using an EVOM voltmeter with an ENDOHM-12 (World Precision Instruments, Sarasota,FL, United States). Electrical resistance was expressed as Ω × cm2. DSS was applied onto the cells to reproducein vitrothe membrane breach it is known to inducein vivoand characterize the loss of membrane integrity. TEER was calculated by subtracting the resistance of blank filters from that of filters covered with a monolayer of parental HT-29, HT-29 Cx43D, or HT-29 Cx43-cells.

Evans blue assay

Epithelial cells form tight junctions that prevent paracellular transit. Evans blue is a dye that strongly binds to serum albuminin vivoandin vitro, becoming a protein tracer[33]. When Evans Blue is added on the apical aspect of cells in culture, it is retained in this compartment due to the established epithelial barrier. Any perturbation of barrier integrity will result in seeping of Evans Blue to the basolateral aspect of the cells. HT-29, HT-29 Cx43D, and HT-29 Cx43-cells were grown on transparent PET membrane cell culture inserts with 0.4 μm-pore size (Corning) until confluent (monolayer). Evans Blue solution (Sigma-Aldrich) was prepared in a 1% bovine serum albumin (cell culture grade; GIBCO®,Paisley, Scotland) at a concentration of 170 μg/mL and then filtered through 0.22 μm-filters (Corning®,Wiesbaden, Germany). At confluence, cells were exposed to 2% DSS for 24 h. Cells were then washed twice with PBS and 400 μL of Evans Blue solution were added on top of the cells (seeded in inserts).Plate wells were rinsed and 1 mL of PBS was added into each well. Cells were then incubated at 37 °C.Every 30 min, 200 μL of solution from the well were collected and replaced with fresh 200 μL PBS, for a total of 2 h. The optic density of collected solution was recorded at 630 nm and concentrations of Evans Blue were calculated.

DSS-induced colitis mouse model

This study was approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Utilization Committee of the American University of Beirut (IACUCC# 18-03-476). The acute DSS-induced colitis mouse model was performed as previously reported[34]. The DSS colitis model in mice is a well-established model for IBD. Using this mouse model, studies have shown disruption of the epithelial barrier function with the infiltration of immune cells, as well as an uncommon production of cytokines[35,36]. In addition, DSS has been previously usedin vitroto induce a cell membrane breach in a monolayer of colon cells, mimicking the intestinal mucosal barrier. DSS exposure resulted in impairment of protein trafficking and alterations in membrane composition in the intestinal Caco-2 cell line[37,38], resembling the intestinal mucosa integrity breach that occurs in IBD.

In this study, carbenoxolone (CBX) was used as a non-specific GJ inhibitor, injected intraperitoneally at the dose of 30 mg/kg every other day. Briefly, adult BALB/c male mice were distributed into the following experimental groups, each comprised of five mice: (1) Control group that received normal drinking water with no CBX injections; (2) CBX group that received normal drinking water with CBX injections starting on day 11; (3) DSS group where mice were exposed to 2.5% DSS in their drinking water for 10 d, followed by normal drinking water as of day 11; and (4) DSS + CBX group that received DSS-containing drinking water for 10 d followed by CBX injections. All four groups were given normal drinking water from day 11 to day 21 (end of experimental duration) and body weights were measured daily. All mice were given standard chowad libitumand were housed in a temperature-controlled environment on a 12-h automated light/dark cycle. On day 21, mice were anesthetized with isoflurane and then euthanized by cervical dislocation. Colon lengths were measured using a ruler and colon tissues were collected for histological and molecular examinations to assess tissue integrity and expression of inflammatory markers, Cx43, and TET-2.

RNA isolation

Cells in culture: Cells were washed with PBS and total RNA was extracted using the RNeasy®Plus mini kit (Qiagen) aspermanufacturers’ instructions.

Cryopreserved tissues: Colon tissues from experimental mice were collected and snap-frozen in liquid nitrogen. RNA was then isolated using TRI reagent (Sigma), aspermanufacturers’ protocol. Since DSS treatment inhibits mRNA amplification from tissues by quantitative polymerase chain reaction (qPCR)by inhibiting the activities of both polymerase and reverse transcriptase, RNA purification for all samples in all conditions was done by the lithium chloride method according to Viennoiset al[38].

qPCR

One μg of total RNA was reverse-transcribed to cDNA using the iScriptTM cDNA synthesis kit (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA, United States). qPCR was conducted using a homemade SYBR green mix in a CFX96 system (Bio-Rad). Products were amplified using primers that recognize Cx43, TET-2, IL-1β, TNF-α, and glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH) (Table 1). PCR settings were as follows: A precycle at 95 °C for 5 min followed by 40 cycles consisting of 95 °C for 10 s, 52-62 °C for 30 s, and 72 °C for 30 s with a final extra-elongation at 72 °C for 5 min. The fluorescence threshold cycle value (Ct) was obtained for each gene and normalized to the corresponding GAPDH Ct value. All experiments were carried out in technical duplicates and independently performed at least three times.

Protein extraction and Western blot

Cells in culture: Cells were washed with ice-cold PBS, and scraped on ice in lysis buffer (0.5 M Tris-HCl buffer, pH 6.8; 2% SDS, and 20% glycerol) containing protease and phosphatase inhibitors (Roche, Basel,Switzerland).

Cryopreserved tissues: Snap-frozen mouse colon tissues were homogenized on ice in ice-cold RIPA buffer containing 10% of a 0.5 M Tris-HCl buffer, pH 7.5, 3% of 5 M NaCl, 1% NP-40, 10% sodium deoxycholate, and 1% SDS as well as phosphatase and protease inhibitors.

The lysate was then sonicated. Proteins were quantified, loaded onto 10% SDS-polyacrylamide gels,and subjected to electrophoresis. Migrated proteins were transferred to polyvinylidene fluoride membranes (Bio-Rad) and membranes were blocked with 5% fat-free milk in PBS. Membranes were then incubated with either human or mouse primary antibodies for 3 h at room temperature or overnight at 4 °C. Primary antibodies were hybridized with horseradish peroxidase-conjugated secondary antibodies (anti-rabbit: SC-2357 and anti-mouse SC-2005; Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Dallas,TX, United States) and blots were visualized using an enhanced chemiluminescence detection kit.GAPDH (MAB5476; Abnova, Taipei, Taiwan) and β-actin (A2228; Sigma-Aldrich) were used as loading controls. The quantification of bands was performed using the ImageJ software (United States National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD, United States). Immunoreactivity of proteins under study was reported as a ratio of protein-of-interest expression to the housekeeping gene used as loading control.

Table 1 Quantitative polymerase chain reaction human and mouse primer sequences

Specimens from human patients

Archived formaldehyde-fixed paraffin-embedded (FFPE) colon blocks (ulcerative colitis, sporadic colon adenocarcinoma and normal) were obtained from the American University of Beirut Medical Center. All patients’ identifiers were kept confidential from the study team.

Histological evaluation

Sections obtained from animals and human samples were stained with hematoxylin and eosin (H&E)for observation under the light microscope (CX41; Olympus, Tokyo, Japan).

Immunofluorescence microscopy

Cells in culture: Cells were grown on coverslips and then fixed either with 4% paraformaldehyde and permeabilized with 0.05% Triton X-100 for 20 min for Cx43 probing (SAB4501175; Sigma-Aldrich) or with ice-cold methanol at -20 °C for TET-2 (ab94580; Abcam, Cambridge, United Kingdom) and 5-hmC(ab214728; Abcam) probing before blocking of non-specific binding.

FFPE tissues: Human and murine 5-μm-thick tissue sections were immune-stained using antibodies against Cx43, TET-2, 5-hmC, and CD68 (ab201340, Abcam, United States). Briefly, paraffin blocks were sectioned using a microtome and sections were mounted onto glass slides. Specimens were deparaffinized in xylene and rehydrated using a gradient series of alcohol to water. Antigen retrieval was performed by incubating sections in sodium citrate buffer (pH 6.0) in a steamer for 30 min. Sections were allowed to cool, then washed twice with deionized water before blocking of non-specific binding.Non-specific binding was blocked with 5% normal goat serum (Chemicon, Burlington, MA, United States) in PBS for 1 h in a humidified chamber and incubated with the primary antibody against Cx43,TET-2, and 5-hmC overnight at 4 °C. Cells were then washed and incubated with IgG-conjugated secondary antibody: Either Texas Red (T862; Life Technologies, Carlsbad, CA, United States) or Alexa Fluor 488 (A11070; Life Technologies) at 1 μg/mL for 1 h at room temperature. Nuclei were counterstained with 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole at 1 μg/mL for 10 min. Coverslips were then mounted onto the glass slides using Prolong Anti-fade kit (Life Technologies).

Slides were examined under a fluorescence microscope and images were acquired using a 63×/1.46 Oil Plan-Apochromatic objective (on the laser scanning confocal microscope LSM 710, operated by the Zeiss LSM 710 software; Carl Zeiss, Oberkochen, Germany).

Statistical analyses

Numerical values were expressed as mean ± SEM or mean ± SD. ThePvalue was determined and considered significant forP< 0.05. Differences between experimental groups were assessed using Studentt-test, one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) or by two-way ANOVA followed by Tukey's multiple comparisons test.

RESULTS

Characterization of the HT-29 cell model used in this study

In an attempt to investigate TET-2 modulation in the context of different Cx43 expression levels in HT-29 cells, Cx43 was upregulated (HT-29 Cx43D cells) or downregulated (HT-29 Cx43-cells). Increases and decreases in Cx43 levels were reflected at the translational level: Western blot analysis (Figure 1A)shows upregulation of exogenous Cx43 protein levels in HT-29 Cx43D and loss of endogenous Cx43 protein expression in HT-29 Cx43-cells compared to parental HT-29 cells (P< 0.001). Figure 1B also shows increased expression of Cx43 in HT-29 Cx43D cells and their localization at the cell periphery,where they form GJ plaques, and a decrease in Cx43 levels in HT-29 Cx43-cells.

Cells manipulated forCx43gene showed differential proliferation rates 48 h and 72 h post-seeding.As depicted in Figure 1C, Cx43 upregulation (HT-29 Cx43D cells) significantly decreased the number of viable cells compared to parental HT-29 cells (P< 0.05 at 48 h andP< 0.001 at 72 h). However, cells devoid of Cx43 (HT-29 Cx43-cells) demonstrated a significantly greater proliferation rate compared to parental HT-29 cells at 48 h and 72 h post-seeding (P< 0.001). The increased proliferation rate of HT-29 Cx43-cells was also accompanied by increased migratory potential, as suggested by the wound healing and the invasion assays (Supplementary Figure 1). Compared to parental cells, HT-29 Cx43-cells seemed more efficient at closing the artificially created gap (P< 0.05).

These observations are in accordance with the tumor suppressor role of Cx43, greatly inhibiting the proliferation of HT-29 cells.

Modulation of TET expression in HT-29 cellular subsets

Transcriptional levels of TET-1, TET-2, and TET-3 were evaluated in HT29 cells, manipulated for Cx43 expression. TET-2 specifically demonstrated the highest transcriptional levels between all three TET genes (Figure 1D). TET-2 protein expression was verified by immunofluorescence in parental HT-29 cells (Figure 1D). While TET-1 and TET-3 levels were not significantly different in HT-29 cells expressing lower or higher levels of Cx43, TET-2 levels significantly increased in HT-29 Cx43-cells compared to parental HT-29 (P< 0.05) and to HT-29 Cx43D (P< 0.001) cells.

For the remainder of this study, TET-2 expression levels and 5-hmC mark were evaluated given the greater expression of TET-2 in HT-29 cells and the prevalence of loss-of-function mutations of TET-2 in cancer[21,39-41].

Inflammation induces increase in Cx43 and TET-2 expression levels in HT-29 cells

In order to explore a potential pattern of expression for TET-2 and Cx43 in inflammation, parental HT-29, HT-29 Cx43D, and HT-29 Cx43-cells were screened for TET-2 mRNA and protein expressions, as well as 5-hmC marks by immunofluorescence using an antibody against 5-hmC, a product of the reaction catalyzed by TET-2. In Cx43-expressing cells, the addition of inflammatory media (supernatant from activated THP-1 cells) resulted in upregulation of Cx43 (Figure 2A). Similarly, under inflammatory conditions, all three cellular subsets upregulated their TET-2 expression (P< 0.05) at the transcriptional and translational levels (Figure 2B). Interestingly, HT-29 cells down-regulating Cx43 showed higher expression of TET-2 compared to parental cells or cells overexpressing Cx43 (Figure 2B). The 5-hmC marks also increased with increased TET-2 levels in HT-29 Cx43-cells. Levels of TET-2 and 5-hmC both increased in cells exposed to inflammation, as shown by quantified immunofluorescence micrographs(Figure 2C). Changes in TET-2 expression were less pronounced in HT-29 Cx43D cells than in HT-29 Cx43-cells. This trend was also evident with the 5-hmC marks (Figure 2C) where increased expression of TET-2 correlated with increased amounts of 5-hmC.

In order to strengthen these findings, experiments were performed on Caco-2 cells. Levels of Cx43 and TET-2 were also upregulated in Caco-2 cells exposed to inflammatory medium (Figure 2D), with a five-fold increase in Cx43 levels (P< 0.001) and two-fold increase in TET-2 levels (P< 0.01).

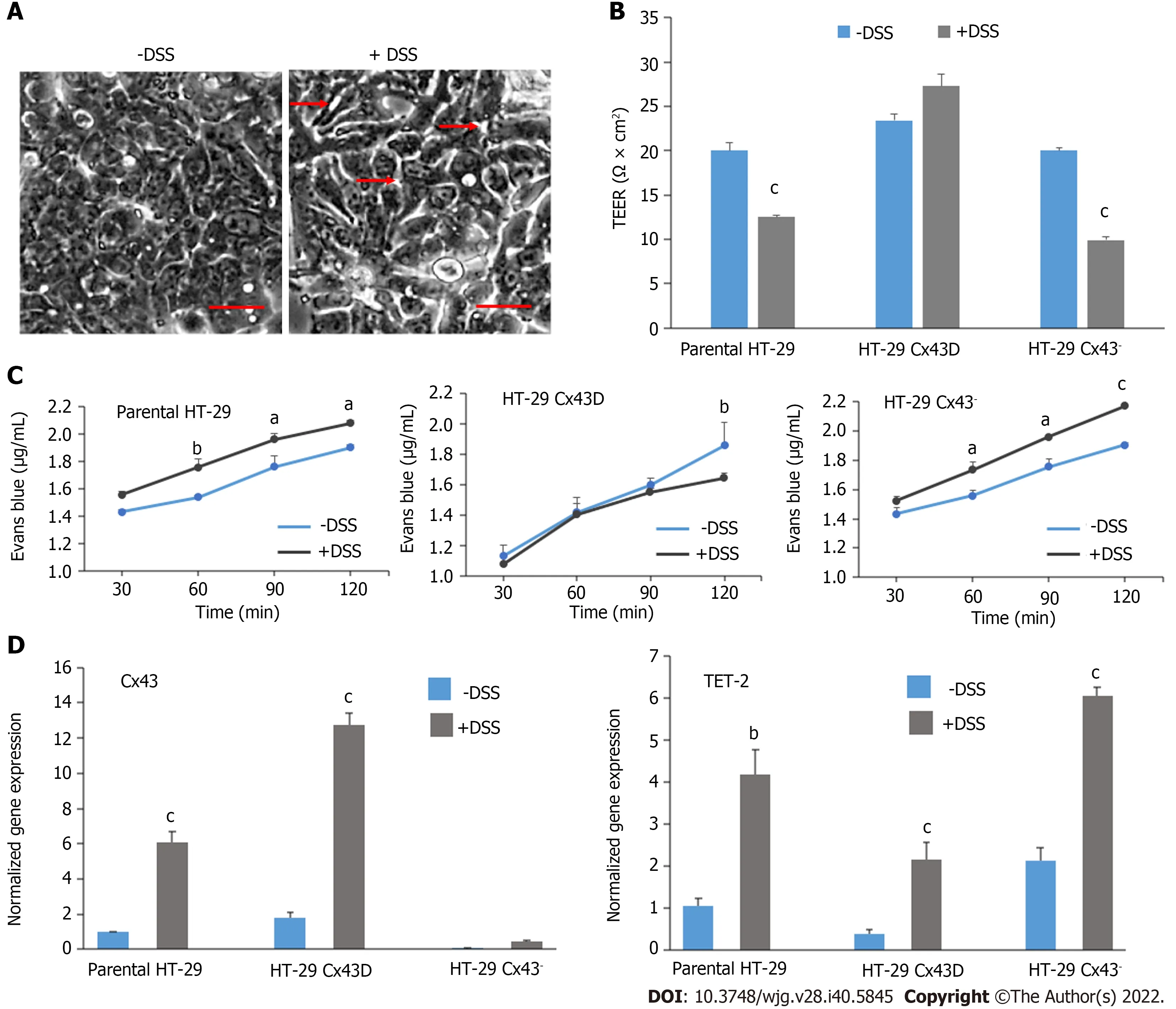

Downregulating Cx43 contributes to the disruption of epithelial membrane integrity

Figure 1 Characterization of the in vitro HT-29 cell model. A: Western blot of connexin 43 (Cx43) protein expression in parental HT-29, HT-29 Cx43-Dendra (Cx43D), and in HT-29 Cx43- cells. Bar graphs display mean densitometric analysis (of three independent experiments) after normalizing protein expression to glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH); B: Immunofluorescence micrographs of parental HT-29 and HT-29 Cx43- cells, as well as a fluorescent micrograph of HT-29 cells transduced with the GFP-Cx43 construct. Highly GFP positive cells were sorted using BD-Fluorescence-Activated Cell Sorting cell sorter,generating the HT-29 Cx43D. Scale bar 10 μm; C: Cells were counted at three different time points (24, 48 and 72 h), using the trypan blue dye exclusion assay.Compared to parental HT-29 cells, HT-29 Cx43D cells had a slower proliferation rate and HT-29 Cx43- cells a faster proliferation rate at 48 and 72 h; D: Histograms show normalized gene expression of ten-eleven translocation (TETs) in parental HT-29, HT-29 Cx43D and HT-29 Cx43- cells, as detected by quantitative polymerase chain reaction (qPCR). TET-2 was the highest expressed TET in HT-29 cells, and cells with differential Cx43 expression also had significantly different TET-2 expression levels. The inset is an immunomicrograph of TET-2 in HT-29 C43D cells. Scale bar 5 μm. Results are presented as means ± SEM of three independent qPCR runs in duplicates. One-way ANOVA, aP < 0.05; bP < 0.001; cP < 0.0005. Cx43: Connexin 43; GAPDH: Glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate dehydrogenase.

Parental HT-29, HT-29 Cx43D, and HT-29 Cx43-cells were grown as monolayers and exposed to 2% DSS for 24 h to evaluate if differential Cx43 levels would have any bearing on DSS-induced membrane integrity breach. DSS was previously shown to impair IEC membrane integrityin vitro[42]and it was used in our study to induce membrane injury similar to that observed upon chronic inflammation.Figure 3A shows that DSS resulted in decreased cell contacts and increased spaces between cells (red arrows), indicating loss of membrane integrity. The TEER assay was performed to assess how Cx43 modulation affects membrane integrity in the presence of DSS. Figure 3B shows that, in the absence of DSS, differentially expressed Cx43 had no major impact on epithelial barrier integrity, with an average TEER of 20 Ω × cm2in parental and in HT-29 Cx43-cells and 23 Ω × cm2in HT-29 Cx43D cells. However,the addition of DSS resulted in a significant decrease in TEER values by approximately 37% in parental cells and 50% in HT-29 Cx43-cells (P< 0001). Therefore, overexpression of Cx43 in HT-29 Cx43D cells seemed to be protective against DSS-induced loss of membrane integrity (Figure 3B).

Figure 2 Connexin 43 and ten-eleven translocation-2 expression increases in cells exposed to inflammation. Parental HT-29, HT-29 connexin 43-Dendra (Cx43D), and HT-29 Cx43- cells were exposed to inflammatory conditioned media (CM) obtained from activated THP-1 cells for 24 h. A: Histograms show the normalized gene expression of Cx43, as detected by quantitative polymerase chain reaction. Cx43 mRNA levels increase in parental HT-29 and HT-29 Cx43D, in the presence of inflammatory media. Western blot of endogenous Cx43 and exogenous Cx43D protein expression in parental HT-29, HT-29 Cx43D, and in HT-29 Cx43- cells. Densitometric analysis (ratio of protein-of-interest to loading control band intensity) shows a slight increase in Cx43 levels upon exposure to inflammation;B: Bar graphs show ten-eleven translocation-2 (TET-2) transcriptional levels increase in all three HT-29 cellular subsets when exposed to CM. Western blots of TET-2 and densitometric analysis shows increased protein levels of TET-2 in CM-treated cells; C: Immunofluorescence images showing TET-2 expression and 5-hmC marks in parental HT-29, HT-29 Cx43D, and HT-29 Cx43- cells. Bar graphs in the right panel reflect mean fluorescence intensity of at least five different fields acquired from three different experiments. Levels and activity of TET-2 increase in all CM-exposed cells. Scale bar 5 μm; D: Bar graphs display levels of Cx43 and TET-2 in Caco-2 cells exposed to CM. Fluorescent micrographs show increased levels of TET-2 in the nucleus upon exposure to CM. Scale bar 5 μm. Experiments were repeated at least three different times. One-way ANOVA, aP < 0.05; bP < 0.001; cP < 0.0005. TET-2: Translocation-2; Cx43: Connexin 43; GAPDH:Glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate dehydrogenase; MFI: Mean fluorescence intensity.

The Evans Blue permeability assay was then performed to evaluate the monolayer integrity under DSS exposure and in cells with different Cx43 expression status. The level of cell permeability or“leakage” was correlated to the concentration of Evans Blue measured at the bottom of the well. As shown in Figure 3C, after 60 min of incubation with Evans Blue, the concentration of the dye significantly and rapidly increased in DSS-treated parental HT-29 (P< 0.05) and HT-29 Cx43-cells (P<0.0001). However, within the two-hour timeframe, cells overexpressing Cx43 (HT-29 Cx43D cells) had not leaked substantial levels of Evans Blue dye.

DSS was subsequently used to reproduce the murine colitis model to evaluate modulation of Cx43 and TET-2 levels in the inflamed colons of mice. Figure 3D shows that upon exposure of HT-29 cells to DSSin vitro, levels of Cx43 and TET-2 vary. Specifically, in Cx43-expressing cells, DSS exposure results in upregulation of Cx43 (P< 0.001). Levels of TET-2 also significantly increase in all HT-29 cellular subsets (P< 0.01).

In summary,in vitroresults suggest that inflammation leads to upregulation of Cx43 and of TET-2 in HT-29 cells. TET-2 upregulation was more pronounced in HT-29 cells devoid of Cx43. Moreover, Cx43 knockdown rendered HT-29 cells more sensitive to DSS-induced membrane integrity breach, in favor of a role of Cx43 protein in the maintenance of epithelial barrier integrity. Modulation of Cx43 and TET-2in vitrodisplayed similar trends whether cells were exposed to conditioned inflammatory media(obtained from activated THP-1 cells) or to DSS (subsequently used in the colitis mouse model).

Figure 3 Dextran sulfate sodium treatment disrupts the integrity and permeability of intestinal epithelial barrier, notably in HT-29 connexin 43- cells. A: Light microscopy images of HT-29 cells in the presence or absence of 2% dextran sulfate sodium (DSS). Scale bar 50 μm; B: The membrane integrity of parental HT-29, HT-29 connexin 43-Dendra (Cx43D), and HT-29 Cx43- cells in the presence or absence of 2% DSS was measured by transepithelial electrical resistance (TEER). Bar graphs indicate average TEER measurements; C: Membrane permeability was evaluated by Evans Blue permeability assay in all three cell subsets. Levels of Evans Blue that crossed are measured by spectrophotometry and are plotted as means over time; D: Quantitative polymerase chain reaction data show that transcriptional levels of Cx43 and ten-eleven translocation-2 (TET-2) significantly increase in DSS-treated cells. All experiments have been repeated at least three times. Two-way ANOVA, aP < 0.05; bP < 0.001; cP < 0.0005. Cx43: Connexin 43; DSS: Dextran sulfate sodium; TEER:Trans-epithelial electrical resistance.

An established and widely used DSS-induced colitis mouse model was reproduced[34]to evaluate Cx43 and TET-2 expression. A subset of mice was also administered CBX, a GJ inhibitor, to examine TET-2 expression modulation in varying functional states of GJs.

DSS-induced colitis in mice is attenuated by CBX-induced GJ blockade

The experimental design was as described in Figure 4A, where each group comprised five mice. Body weight was recorded daily, throughout the 21-d experimental duration. Figure 4B reflects weight changes; while mice in the control group (Group 1) consistently gained weight over the 21-d experiment, mice exposed to CBX alone (Group 2) maintained their baseline weight throughout the experiment. On the other hand, DSS-exposed mice lost a moderate amount of weight until day 10, after which they were switched to normal drinking water (Group 3) and their average weight picked up to almost control group levels. Mice in the DSS group who were injected with CBX starting day 11 recovered some of the weight lost until day 10, but did not reach the normal weight recorded in the control group.

Figure 4 Dextran sulfate sodium induces inflammation in mice and carbenoxolone restores the normal phenotype. A: A flowchart schematizing the in vivo experimental design. BALB/c male mice were distributed into four experimental groups, each comprised of five mice: (1) Control group that received normal drinking water with no carbenoxolone (CBX) injections; (2) CBX group that received normal drinking water with CBX injections starting day 11; (3)Dextran sulfate sodium (DSS) group where mice were administered with 2.5% DSS in their drinking water for 10 d but not subjected to any CBX injections; and (4)DSS + CBX group that received DSS-containing drinking water as well as CBX injections. Mice were given 30 mg/kg CBX via intraperitoneal injections from day 11 every other day to the end of the experiment; B: Variation of animal body weight over 21 d. DSS-exposed mice lost weight. Significance in body weight change was detected between days 4 and 12 in DSS-treated mice, and days 11 and 21 in CBX-injected mice only; C: Hematoxylin and eosin images showing the architecture of mice colon tissues from all experimental groups. Arrows indicate representative sites in each experimental condition. Scale bar 50 μm; D: Colon length was measured at the end of the experiment. DSS-treated mice showed significantly longer colons compared to the control group; E: Bar graphs showing the normalized gene expression of interleukin-1β and tumor necrosis factor-α in mouse colon tissues, as detected by quantitative polymerase chain reaction. Experiments were repeated five times and results are displayed as means ± SEM. One-way ANOVA, aP < 0.05. IL: Interleukin; CBX: Carbenoxolone; DSS: Dextran sulfate sodium; TNF-α:Tumor necrosis factor-α.

At the end of the experimental duration, mice were euthanized and their colons examined and collected for measurement purposes and a biopsy was used for histological and molecular analyses.Histological examination of H&E stained sections of colons showed a disruption of epithelial barrier as well as an increase in infiltrating cells in crypts of colons from DSS-treated mice compared to control.CBX-treated animals seem to have retained (albeit not fully) some normalcy (Figure 4C). DSS-treated mice showed significantly longer colons compared to the control group (P< 0.05). CBX significantly reduced the length of DSS-treated colons to approximately normal levels (P< 0.05) (Figure 4D).

Levels of inflammatory cytokines, IL-1β and TNF-α, previously shown to be modulated in IBD models[12,38,43], were evaluated by qPCR. In accordance with weight changes and colon length indicative of intestinal damage, DSS-treated mice of Group 3 had increased expression of both IL-1β and TNF-α, compared to control Group 1 (P< 0.05) (Figure 4E).

These data propose that CBX alleviates DSS-induced inflammation in mice, as demonstrated by normalized colon length and histology, as well as decreased levels of inflammatory mediator transcripts in colon tissues.

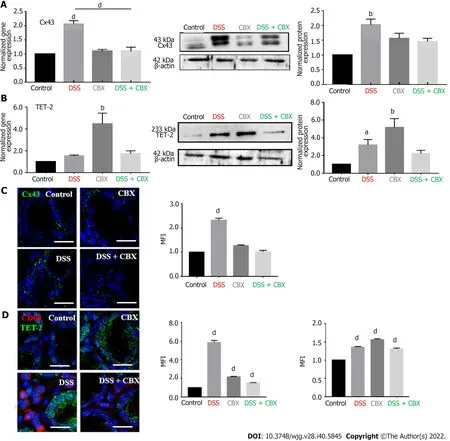

DSS-induced inflammation increases Cx43 and TET-2 expression in vivo

Colon tissues obtained from mice on day 21 (end of experimental duration) were processed for total RNA and protein extraction. Cx43 expression was significantly higher in tissues from mice exposed to DSS both at the transcriptional (Figure 5A,P< 0.0001) and translational levels (Figure 5A, middle and right panels). However, CBX injections restored Cx43 mRNA and protein levels back to control levels.Not only did GJ inhibition attenuate the inflammatory state in the colon, it also led to downregulated Cx43 expression.

Levels of TET-2 were also evaluated in the colon tissues obtained from mice in all four experimental groups. Gene expression analysis pointed to an increase of TET-2 mRNA levels in the CBX-treated group (Group 2, Figure 5B,P< 0.001). In the tissues of mice from Group 4 (DSS + CBX), TET-2 levels were similar to those in the DSS group (slightly, but not significantly, higher than control levels). The same pattern was observed at the protein level (Figure 5B, middle and right panels). Changes in TET-2 levels were accompanied by changes in Cx43 levels, which increased in DSS-treated (inflamed) colons and decreased upon addition of CBX (Figure 5C). Inflammation was further underscored by immunostaining using CD68 antibody. As shown in Figure 5D, levels of infiltrated CD68+cells (macrophages)increased significantly by six-fold in colons of DSS-treated mice as opposed to those of control or CBXtreated mice alone (P< 0.0001). In accordance with CBX effects on inflammatory mediators and histological aspects, CBX injections following DSS exposure resulted in a decreased amount of macrophages. Sections from colons of mice in the DSS group also showed considerable levels of TET-2 protein in epithelial cells with neighboring macrophages, both indicative of an active inflammatory process. TET-2 levels increased further in colons of CBX-treated mice. In addition, and consistent with transcriptional and translational data, CBX-treated mice had upregulated TET-2 protein levels in their colons (Figure 5D). Immunofluorescent micrographs reflect TET-2 level increase in mucosal cells,though not to the same extent as qPCR data; due to the contribution of TET-2 mRNA from CD68+macrophages in the vicinity of IECs.

These data indicate that inhibiting GJs in inflamed tissues mitigates DSS-induced inflammation. In addition, the increase in Cx43 expression upon exposure to DSS is accompanied by an increase in TET-2 protein expression levels, and disabling GJs by CBX is paralleled by a significant increase in TET-2 levels. Data therefore suggest that, under inflammatory conditions (DSS), GJ inhibition by CBX restores Cx43 levels down to control. In accordance within vitrodata where HT-29 Cx43-cells had upregulated TET-2 levels, chemical inhibition of Cx43in vivoalso was accompanied by increased TET-2 levels.

Collectively,in vitroandin vivodata indicate that under inflammatory conditions, levels of both TET-2 and Cx43 increase.

Cx43 levels increase and TET-2 levels decrease in colons of patients with ulcerative colitis

In an attempt to correlatein vitroandin vivofindings with clinical data, FFPE colon biopsies from normal non-dysplastic non-inflamed colons (n= 7), ulcerative colitis (n= 5), and colon adenocarcinoma (n= 7) patients were obtained anonymously. Sections were stained with H&E for light microscopy, as well as with antibodies against CD68 (macrophage marker), Cx43, and TET-2 for immunofluorescence analyses.

Histological staining exposed a clearly disorganized intestinal mucosal layer in ulcerative colitis and sporadic colon adenocarcinoma tissues as compared to normal tissues (Figure 6A). The disrupted architecture was due to extensive immune activity in the tissues underlying the mucosa. Figure 6B shows CD68+macrophages infiltrating tissues from ulcerative colitis patients (P< 0.0001), underscoring the inflammatory profile. Tissues obtained from patients with sporadic adenocarcinoma of the colon also displayed macrophage foci, but to a much lesser extent than ulcerative colitis tissues (P< 0.001).Although comparable to control in terms of fluorescence intensity, CD68+cells in the adenocarcinoma specimen were not uniformly distributed in the tissue.

Moreover, Cx43 and TET-2 expression and localization were evaluated by immunofluorescence(Figure 6C and D). Consistent with data obtainedin vitro(Figures 2 and 3) andin vivo(Figure 5), Cx43 protein levels were significantly increased in ulcerative colitis (i.e.inflamed) tissues (P< 0.005) and sharply decreased in adenocarcinoma. Unlikein vitroandin vivodata that reflect parallel patterns of Cx43 and TET-2 expression in inflammatory conditions, Cx43 level increase in ulcerative colitis was accompanied by a decrease in TET-2 expression (P< 0.001). This observation, however, resembles thein vitroscenario illustrated in Figure 2. In fact, while TET-2 expression had increased upon exposure of cells to an inflammatory milieu, Cx43 upregulation in HT-29 Cx43D cells was associated with lower overall TET-2 expression compared to parental cells, and Cx43 knockdown resulted in elevated TET-2 levels.

DISCUSSION

In various pathologies, including inflammation and cancer, the alteration of the expression, regulation,and association of junctional complexes with other proteins have been reported. Epigenetic methylation and demethylation processes are also major players in a cell’s malignant transformation. Specifically,GJ-forming Cx43 and demethylating enzyme TET-2 have both been documented to be impaired in inflammation and cancer[10-12,19,20].

Figure 5 Dextran sulfate sodium increases connexin 43 and ten-eleven translocation-2 expressions in vivo. A: Left panel: Histograms show the normalized gene expression of connexin 43 (Cx43) in mice colon tissues, as detected by quantitative polymerase chain reaction (qPCR). Middle panel: Western blot of Cx43 protein in mouse colon tissues. Right panel: Densitometric analysis of protein expression after normalization to β-actin. Dextran sulfate sodium (DSS)-treated mice had the highest expression of Cx43 in their colons; B: Left panel: Histograms display the normalized gene expression of ten-eleven translocation-2 (TET-2) in mouse colon tissues, as detected by qPCR. Middle panel: Western blot of TET-2 protein expression in mouse colon tissues. Right panel: Densitometric analysis of protein expression after normalization to β-actin. DSS exposure resulted in enhanced TET-2 transcription and carbenoxolone inhibition of gap junctions significantly increased TET-2 expression; C: Immunofluorescence images of colon tissues stained for Cx43 with the mean fluorescence intensity (MFI) analysis. Scale bar 20 μm;D: Immunofluorescence images of mouse colon tissues stained for CD68 and TET-2. Histograms reflect the MFI analysis. High levels of CD68+ cells correlated with greater expression of Cx43 and TET-2 in DSS-exposed mice. Scale bar 10 μm. Experiments were repeated five times. One-way ANOVA, aP < 0.05; bP < 0.005; dP <0.0001. MFI: Mean fluorescence intensity; CBX: Carbenoxolone; DSS: Dextran sulfate sodium.

Figure 6 Modulation of connexin 43 and ten-eleven translocation-2 expression in human colon tissues under pathological conditions. A:Hematoxylin and eosin images of human colon tissues. Compared to normal (histopathologically unchanged) samples, tissues from inflamed (ulcerative colitis) and sporadic malignant colons show disorganization of colon crypts and infiltration of immune cells within the lamina propria. Scale bar 50 μm; B: Immunofluorescence images of CD68+ cells (macrophages) and connexin 43 (Cx43) show that Cx43 expression increases in inflamed tissues. Scale bar 10 μm; C: Immunofluorescence images of ten-eleven translocation-2 (TET-2) in human colon tissues (upper panel: Low magnification; lower panel: Higher magnification). TET-2 protein was minimally detected in ulcerative colitis and colon adenocarcinoma tissues. Scale bar 10 μm; D: Mean fluorescence intensity (MFI) analyses reflecting the expression of CD68, Cx43, and TET-2. One-way ANOVA, bP < 0.005; dP < 0.0001. MFI: Mean fluorescence intensity; TET: Ten-eleven translocation.

Studies have shown that the inflammatory response relies in part on intercellular communication mediated by channel-forming connexins. The role of GJ-mediated signaling in the initiation of inflammation is mainly through the transfer of ATP between neighboring cells. ATP molecules are then released in the extracellular environment where they act as signaling molecules that activate purinergic receptors, amplifying the inflammatory response[10]. Wonget al[11]partly elucidated the role of Cx43 in intestinal epithelial barrier injury. TLR activation in the disrupted intestinal epithelium translates intracellularly into Cx43 transcription, translation, post-translational modification, and assembly into connexons. GJIC regulates intestinal epithelial function during both acute and chronic inflammation[11]. Furthermore, Al-Ghadbanet al[12]demonstrated a role of GJs in the pathogenesis of IBD by a direct communication between IECs and macrophages enhanced by basement membrane degradation[12]. Long-term IBD associates with amplified risk of colon carcinogenesis, and the deregulation of connexin expression is regarded as one of the hallmarks of different cancers. Shilovaet al[44]reviewedin vitroandin vivostudies that point at a correlation between the loss of connexin expression and cancer onset. In fact, downregulation of Cx26, Cx32, and Cx43 accompanies the development of human bladder cancer, hepatocarcinoma, and breast cancer, respectively[44]. A recent study on breast cancer proposed that Cx43 upregulation in a triple negative breast cancer cell line led to a reversal of its mesenchymal phenotypein vitroand to a decreased metastatic potentialin vivo[7]. While connexin downregulation is observed in many cancers, elevated Cx43 levels have also been associated with increased malignancy. In a hepatocellular carcinoma cell line, Cx43 was shown to enhance malignancy by inhibiting Cx32-mediated GJIC[45], and, in prostate cancer, Cx43 promoted invasion and metastasis[46]. Variability of data on connexin involvement in cancer onset and progression warrants more research to identify the underlying factors that dictate a tumor-suppressing or tumor-enhancing activity of connexins.Epigenetic regulation of various genes could explain the differential expression of tumor-suppressor and tumor-enhancer genes in inflammation and cancer onset and progression.

The role of demethylating enzyme TET-2 in IBD and colorectal adenocarcinoma has not been fully described. In fact, TET proteins have mostly been studied in hematological malignancies. TET-1 was characterized as a partner gene to theMixed-Lineage Leukemiagene in acute myeloid leukemia (AML),and theTET-2gene was described in a study on the myelodysplastic syndrome[47]. Recent investigations report that frequent point mutations in theTET-2gene can lead to the truncation of the resulting protein and loss of enzymatic activity, reflected by reduced global levels of the 5-hmC marks in AML patients[41,48]. However, although mutations in theTET-1andTET-3genes are rare in hematological malignancies compared toTET-2, both still exhibit a tumor-suppressor role: TET-1 in B-cell lymphomas[41]and TET-3, together with TET-2, in murine aggressive myeloid cancer[49]. Mutations and reduced expression of TET proteins were also observed in solid tumors, and decreased translational levels of TETs seem like an important hallmark of different cancers, including cancers of the digestive system[50-52].

In addition to carcinogenesis, a study by Zhanget al[19]shows an anti-inflammatory role for TET-2,which, under inflammatory conditions, repressed IL-6 transcription in dendritic cells and macrophages[19]. Moreover, TET-2-deficient bone marrow-derived dendritic cells and macrophages had high transcriptional levels of IL-6 upon LPS challenge. Another study also reported an increase of TET-2 transcriptional levels in colon tissues from patients with IBD[53].The present study examined the expression of Cx43 and TET-2 in anin vitromodel of colon epithelium, where HT-29 cells were used in their parental state or with upregulated or knocked-out Cx43 in the presence or absence of inflammation(induced by DSS or by the addition of an inflammatory medium). A DSS-induced colitis murine model was used to describe how inflammation modulates the expression of Cx43 and TET-2. Data were then compared to Cx43 and TET-2 expression levels in tissues obtained from patients with ulcerative colitis or sporadic colorectal cancer.

Results from this study indicate that knockout of Cx43 in the HT-29 intestinal cell line leads to disruption of membrane integrity exacerbated by the DSS chemical insult. In Cx43-deficient cells and in mice that were subjected to chemical inhibition of GJs by CBX, loss of GJs was paralleled with increased TET-2 expression, further intensified in the presence of inflammation. In fact, inflammation triggered an upregulation of Cx43 and TET-2 expression in all cell subsets, which is in accordance with the literature[19,47]. An exploratory analysis of human colon samples obtained from ulcerative colitis patients revealed an increase in Cx43 and a decrease in TET-2 protein levels accompanied by the disruption of colon architecture. Though these findings are not aligned with the overall trend implicating TET-2 in intestinal inflammatory conditions, little is known about characteristics of patients whose colon biopsies were examined, including potential pharmacological agents that could lead to TET-2 degradationviaone of the four pathways reviewed by Conget al[54]in October 2020: A caspase-dependent pathway,calpain1-promoted degradation of TET-2, proteasome-dependent degradation, and p53-facilitated autophagy of TET-2 proteins[54]. Moreover, TET-2 seems to be implicated in both initiation of the inflammatory process by activating innate pro-inflammatory signaling pathways and its resolution by inducing the repression of pro-inflammatory mediators[55]. Therefore, the exact status of TET-2 in the colon of IBD patients remains to be elucidated, in light of multiple factors governing post-transcriptional and post-translational TET-2 regulation. In specimens from sporadic colon adenocarcinoma, both TET-2 and Cx43 proteins were considerably downregulated, underscoring the tumor-suppressor role of Cx43.

In the context of IBD (specifically ulcerative colitis) and colon cancer, we propose that Cx43 upregulation in inflamed colons could attenuate or slow down the onset of malignancy. Therefore, loss of Cx43 in tissues from colon cancer could be attributed to a malignant switch, turning off tumor-suppressor genes and activating tumor-promoting genes. The presence of CD68+cells (macrophages) was concomitant with loss of TET-2 expression in the colon adenocarcinoma samples. This could be explained by an immune-active phenotype in tumors, with tumor-associated macrophages having little to no TET-2 expression[55]. A 2018 study reported increased levels of TET-2 in T lymphocytes from colorectal tumor tissues, leading to demethylation and activation of FOXP3 and regulation of regulatory T cell (Treg) function[56], further implicating TET-2 in immune-related processes. In particular, TET-2 has been reported to regulate the innate immune response[57,58]. While it serves to activate the inflammatory response, TET-2 has also been implicated in inflammation resolution, where in response to IL-1/RMyD88 signaling, TET-2 downregulates the expression of inflammatory cytokines, such as IL-6 in innate myeloid cells and IL-1β in macrophages by recruiting HDACs for histone deacetylation[19,57].This property might explain low levels of TET-2 in human ulcerative colitis samples where unresolved inflammation can be attributed to persistent inflammatory cytokines.

TET-2 status and role in digestive cancers remain unclear and variable, depending on the cancer site and grade, but also on possible mutations that could lead to cancer progression and resistance to chemotherapy, as recently reviewed[21].

CONCLUSION

Data presented in this manuscript show that exposure of intestinal cells to inflammation is associated with Cx43 and TET-2 upregulationin vitroandin vivo.We propose that, as part of its potential antiinflammatory role and through its demethylating activity, TET-2 might be responsible for promoting the expression of anti-inflammatory genes and for indirectly repressing the expression of pro-inflammatory genes under inflammatory conditions. Similarly, we hypothesize that the demethylating TET-2 enzyme might promote the expression of tumor-suppressor genes (among others, Cx43) in the inflamed colon.Extrapolating from observations made on human colon samples, a malignant switch could happen in chronically inflamed colons. This malignant switch could be associated with downregulation of TET-2(and potentially other TET enzymes[20,23]) in ulcerative colitis, possibly resulting in the hypermethylation of genes that are relevant in the context of carcinogenesis, such as Cx43. Although we present evidence on the modulation of TET-2 expression and we reiterate the role of Cx43 in intestinal inflammation, further investigation is under way to more solidly explore the mechanism of action behind a potential interplay between Cx43 and TET-2 that might, at least partly and indirectly, bridge chronic inflammation (such as in IBD) and IBD-induced carcinogenesis in the colon.

ARTICLE HIGHLIGHTS

Research perspectives

In vitro, manipulation of TET-2 levels in intestinal cells may yield further insight into the mechanism of action. Methylation studies will also be undertaken. The animal model will be expanded to allow for the development of colon carcinoma, and timed evaluation of molecular players will be performed. More stringent criteria will be implemented for prospective tissue collection from non-inflamed subjects,patients with IBD, and with IBD-associated colorectal cancer.

FOOTNOTES

Author contributions:El-Harakeh M, Saliba J, Haidar M, and Sharaf Aldeen K equally contributed to the study; El-Sabban M conceived and designed the study; Hashash JG, Awad MK, Shirinian M, and El-Sabban M provided the material and resources for the experiments; El-Harakeh M, Haidar M, Sharaf Aldeen K, and El Hajjar L performed the experiments; Saliba J and El-Harakeh M analyzed the data and wrote the manuscript; Shirinian M and Hashash JG critically reviewed the manuscript; Saliba J and El-Sabban M revised the manuscript; All authors read and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Institutional review board statement:Archived formaldehyde-fixed paraffin-embedded (FFPE) colon blocks(ulcerative colitis, sporadic colon adenocarcinoma and normal) were obtained from the American University of Beirut Medical Center (AUBMC). All patients’ identifiers were kept confidential and all samples were anonymous,hence exempted from ethics committee approval.

Institutional animal care and use committee statement:All procedures involving animals were reviewed and approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of the American University of Beirut, No. 18-03-476.

Conflict-of-interest statement:All the authors report no relevant conflicts of interest for this article.

Data sharing statement:Raw data are available upon reasonable request.

ARRIVE guidelines statement:The authors have read the ARRIVE guidelines, and the manuscript was prepared and revised according to the ARRIVE guidelines.

Open-Access:This article is an open-access article that was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution NonCommercial (CC BYNC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is noncommercial. See: https://creativecommons.org/Licenses/by-nc/4.0/

Country/Territory of origin:Lebanon

ORCID number:Mohammad El-Harakeh 0000-0003-3014-3937; Jessica Saliba 0000-0002-9117-8773; Kawthar Sharaf Aldeen 0000-0002-9546-104X; May Haidar 0000-0002-4345-0621; Layal El Hajjar 0000-0003-3123-5577; Mireille Kallassy Awad 0000-0003-1489-8686; Jana G Hashash 0000-0001-8305-9742; Margret Shirinian 0000-0003-4666-2758; Marwan El-Sabban 0000-0001-5084-7654.

S-Editor:Fan JR

L-Editor:Filipodia

P-Editor:Cai YX

World Journal of Gastroenterology2022年40期

World Journal of Gastroenterology2022年40期

- World Journal of Gastroenterology的其它文章

- Heterogeneity of immune control in chronic hepatitis B virus infection: Clinical implications on immunity with interferon-α treatment and retreatment

- Liver transplantation is beneficial regardless of cirrhosis stage or acute-on-chronic liver failure grade: A single-center experience

- Curcumin alleviates experimental colitis via a potential mechanism involving memory B cells and Bcl-6-Syk-BLNK signaling

- Pancreatic acinar cell carcinoma: A comprehensive review

- Management of liver diseases: Current perspectives

- Improving the prognosis before and after liver transplantation: Is muscle a game changer?