Heterogeneity of immune control in chronic hepatitis B virus infection: Clinical implications on immunity with interferon-α treatment and retreatment

Guo-Qing Yin,Ke-Ping Chen,Xiao-Chun Gu

Abstract Hepatitis B virus (HBV) infection is a global public health issue. Interferon-α (IFNα) treatment has been used to treat hepatitis B for over 20 years, but fewer than 5%of Asians receiving IFN-α treatment achieve functional cure. Thus, IFN-α retreatment has been introduced to enhance antiviral function. In recent years,immune-related studies have found that the complex interactions between immune cells and cytokines could modulate immune response networks, including both innate and adaptive immunity, triggering immune responses that control HBV replication. However, heterogeneity of the immune system to control HBV infection, particularly HBV-specific CD8+ T cell heterogeneity, has consequential effects on T cell-based immunotherapy for treating HBV infection.Altogether, the host’s genetic variants, negative-feedback regulators and HBV components affecting the immune system's ability to control HBV. In this study,we reviewed the literature on potential immune mechanisms affecting the immune control of HBV and the clinical effects of IFN-α treatment and retreatment.

Key Words: Hepatitis B virus; Chronic; Functional cure; Heterogeneity; Immunity;Immune control; Interferon-α; Retreatment

INTRODUCTION

Hepatitis B virus (HBV) infection is a major global health problem. It is estimated that over 257 million people are suffering from chronic hepatitis B (CHB) infection[1]. After being infected by HBV, the virus transfers its genome into the nucleus of hepatocytes, where it is converted into covalently closed circular DNA (cccDNA), which has two major roles: Acting as a template for virus replication and acting as a reservoir for long-term virus preservation. Some studies have found that cccDNA persists in the hepatocytes of patients even decades after HBV infection has been resolved[2]. Further, it was shown that part of the viral genome remained integrated into the genomic DNA of the host’s hepatocytes.Therefore, targeted eradication of cccDNA and viral genome in hepatocytes is regarded as the holy grail for curing HBV[3-5], which has not yet been achieved with current therapies.

HBV infection induces various immune responses that lead to heterogeneous immune control associated with the HBV infection[5,6]. Acute HBV infection can be terminated by the host’s adaptive immune responses, characterized by multi-specific and vigorous HBV-specific CD8+T cell responses. In contrast, during CHB infection, the adaptive immune responses are severely depressed due to exhausted or reduced HBV-specific CD8+T-cells[6,7]and dysfunctions in HBV-specific B cells[7-9].Researchers have noticed different outcomes from HBV infection in different populations and races.

Most CHB cases in the Asian population occur during infancy or childhood. However, asymptomatic infection during childhood makes it very challenging for authorities to determine when the infection actually occurred. Further, due to the uncertain timing of hepatitis flares and disease phases, there is little research on this topic in past literature, and little is known about hepatitis flares and intrahepatic immunity. Recently, studies on the partial immune mechanism in CHB have been performed, and important discoveries were made[2-6].

Currently, CHB is treated with nucleoside/nucleotide analogs (NAs) or interferon-α (IFN-α). NAs can target HBV polymerase/reverse transcriptase, inhibit HBV replication and are better tolerated by patients, but they cannot target cccDNA and unavoidably often results in NAs resistance and associated mutations. Since NAs do not directly influence immune response, functional cure with NAs is rarely achieved. In contrast, IFN-α treatment enhances HBV-specific immune control and can result in a partial or functional cure. However, due to poor efficacy with single course IFN-α treatment, since 1996,researchers have begun using IFN-α retreatment to improve the antiviral efficacy in CHB patients[10-15]or sufferers from NAs multi-drugs resistance[15-18].

In this present article, we reviewed the complex interactions between immune cells and cytokines of the immune response network against HBV, the correlation between host genetic variations and hepatitis B, the interplay between HBV components and HBV-specific immune control, and the heterogeneity of HBV-specifical immune control. Based on this foundation, we also discussed the underlying mechanism of IFN-α treatment and retreatment for improved HBV-specific immune control.

HETEROGENEOUS IMMUNITIES DURING HBV INFECTION

The innate and adaptive immunity work together to control immune responses against HBV. Innate immunity is not HBV antigen-specific but still produces T-cell polarizing and inflammatory cytokines that alter the intrahepatic microenvironment for presenting HBV antigens to naïve T cells to establish HBV-specific immunity. In recent years, researchers have recognized adaptive immunity as a crucial player for persistent and efficient immune control of HBV infection, which comprises a complex web of effector cell types. HBV-specific T cells help clearing HBV-infected hepatocytes and reduce the levels of circulating virus, while B cells neutralize viral particles and prevent reinfection[3,19-22]. Thus, their levels ultimately determine the outcome of the disease.

The liver is an immunologically tolerant organ in which most immune cells are suppressed to limit hypersensitivity of immune responses against organ damage and local antigens. Thus, in a healthy state,the proportion of immune cells within the liver is much lower than in the peripheral blood. The difference in immune statuses between the liver and peripheral blood is defined as “immune compartmentalization”. Investigations into the effects of costimulation have shown that Toll-like receptors(TLRs) and Treg cells participate in the intrahepatic immunopathogenesis in patients with HBV infection[3,23-25].

Recognition of HBV components by the innate immunity

Non-specific recognition of HBV components occurs at the molecular/subcellular level by innate immunosensors, namely pathogen-recognition receptors (PRRs) that recognize pathogen-associated molecular patterns (PAMP). The main PRRs that sense viral infection consists of retinoic acid-inducible gene I (RIG-I)-like receptors, nucleotide-binding oligomerization domain-containing protein-like receptors, TLRs, DNA-sensing receptors and C-type Lectin. These PRRs are expressed in epithelial cells,endothelial cells and immune cells. When PRRs interact with their cognate PAMP, downstream signaling pathways cascade, including adaptor/co-adaptor molecules, kinases and transcription factors are activated. This leads to the expression of interferon-stimulated genes (ISGs) and NFκB-inducible or pro-inflammatory genes, and various inflammatory cytokines are secreted. Primary cytokines include various classes of IFNs, pro-inflammatory cytokines and chemokines. These cytokines recruit various immune cells to the HBV-infected site, causing direct or indirect antiviral actions. These immune responses induce T cell proliferation and increase the efficiency of HBV-specific CD8+ T cells[21,26,27].In particular, TLRs in hepatocytes and hepatic non-parenchymal cells (NPCs) have been shown to play vital roles in antiviral immunity. Currently, the use of TLR agonists as therapeutic agents to treat CHB is being validated[7].

In addition to cytokines, innate effector cells also participate in the control of HBV infection. Innate effector cells, including natural killer (NK) cells, γδT cells and mucosal-associated invariant T cells, can restrain the virus but are not specific for controlling HBV. Activated NK cells can induce inflammation in the liver, while activated T cells can be killed by NK cells, thereby reducing HBV-specific T cells.Although NK cells can suppress HBV replication, their activity was shown to be inhibited by transforming growth factor β (TGF-β) and IL-10 in CHB patients[3]. In addition, hepatic PCs, such as KCs and liver sinusoidal endothelial cells, can stimulate innate and adaptive immunity against HBV infection[28,29].

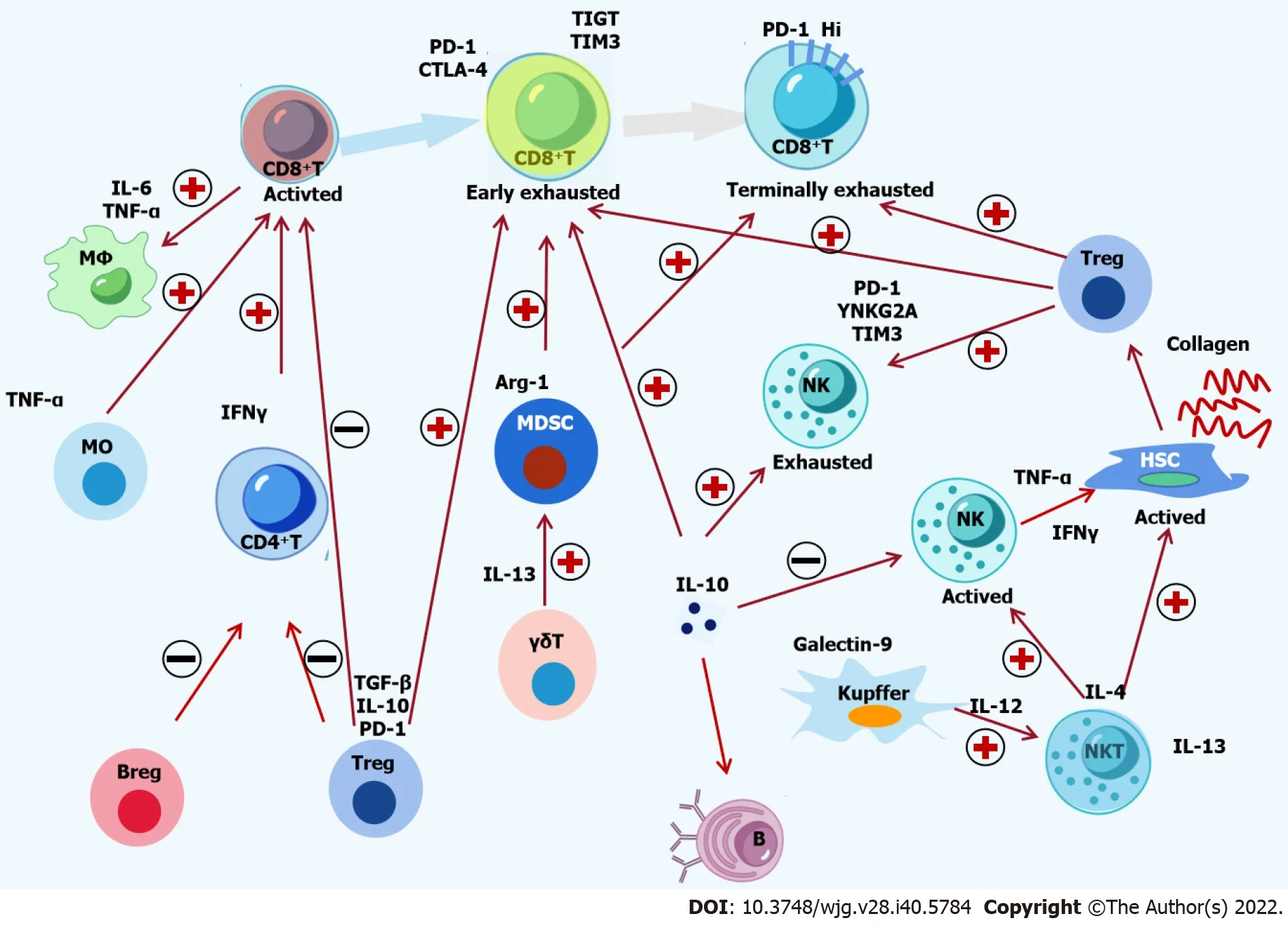

In short, the activation of innate immunity can lead to the production of cytokines, enhance antigen presentation, alter the intrahepatic microenvironment and trigger adaptive immunity (Figure 1).

HBV infection and adaptive immunity

HBV-specific T cells play a vital role in controlling HBV infection, and their immune responses can lead to the resolution of HBV replication. In acute hepatitis B patients, spontaneous viral clearance can occurviamulti-specific CD8+T cell responses against HBV components[3,30]. In contrast, in CHB, the patients suffer from the exhaustion of HBV-specific CD8+T-cell responses throughout the HBV infection. Thus,most research on immune dysfunction focus on the activity of T cells, including CD8+and CD4+T-cells.

CHB is associated with the exhaustion of HBV-specific CD8+T-cells, marked by compromising functionality, such as reduced production of antiviral cytokines and immunodulatory cytokines and impaired proliferative capacities, defined as T-cell exhaustion[31,32]. HBV-specific CD8+T-cell exhaustion can be induced by: (1) Gradual aggravation of CD8+T-cells dysfunction and decreasing inflammatory cytokines production; (2) Increase in checkpoint inhibitors and immunosuppressive cytokines; (3) Epigenetic alterations leading to unrecoverable CD8+T-cell functions; (4) Alterations in CD8+T-cell phenotype; (5) Mitochondrial dysfunction and glycolysis downregulation, (6) Decrease in cell detection rate; and (7) Terminal exhaustion and physical deletion of HBV-specific CD8+T-cells.

In acute hepatitis B, CD4+T-cells have an important but indirect role in cleaning the virus. Th1-polarized CD4+T-cells regulate and maintain CD8+T-cell responses, contributing to HBV clearance. In contrast, during chronic HBV infection, the activation and upregulation of CD4+CD25+Treg-cells suppress effective antiviral immune responses by inhibiting IFN-γ secretion, which inhibits the proliferation and cytokine secretion of CD4+and CD8+T-cells[7,30]. Figure 1 illustrates the complex interactions between immune cells and cytokine within the immune response network. The immune cells and their related cytokines are presented in Table 1.

HBV components inhibit innate and acquired immunity

HBV is believed to have existed in the human population for thousands of years and evolved with humans. During this evolution process, HBV has developed a particular lifecycle based on its unique replication mode through cccDNA and viral components that can adapt and suppress its host's immunity. Although the innate immunity can differentiate between different HBV components, HBV virion, antigens and peptides are still able to attack the TLR signaling pathway, resulting in negligible ISGs or IFNs secretions[4,7].

Table 1 Immune cells and their corresponding cytokines released

Among the ISGs is the apolipoprotein B editing complex (APOBEC) gene. APOBEC3A/B has been shown to cause cccDNA degradation, while APOBEC3G can inhibit HBV replication. However,APOBEC3G expression is often reduced by HBsAg[32].

A viral protein known for influencing HBV replication is HBx. It can interact with the cellular proteins in hepatocytes to increase viral replication by impairing IFN signaling and enhancing HBV gene expression[33-35]. Further, it was shown that HBV antigens could inhibit CD8+T-cell efficiency.Antagonist functions may provide a means for HBV to escape immune detection. Considering that certain CD8+T-cell epitopes in hepatitis B core antigen (HBcAg) or HBsAg can act as T-cell receptor(TCR) antagonists, their binding to TCR can lead to the suppression of CD8+T-cell response, thus decreasing their efficiency (Figure 2). In addition, the chronicity of HBV infection was shown to be promoted by HBeAgviathe induction of CD8+T-cell tolerance[36].

Mechanisms of immune escape in antigen-presenting cells/HBV specific-CD8+ T-cells

When the HBV protein is swallowed by antigen-presenting cells (APCs), this protein is digested into tiny pieces, which are transferred onto human leukocyte antigen (HLA) antigens. The HLA antigen complex on APCs is then displayed to T cells, which produce effector molecules to eliminate HBV.However, when HBV enters a hepatocyte, it enhances intracellular survival at the expense of higher levels of HBV replication. Thus, HBV-infected hepatocytes produce a large number of HBV antigens that can, in turn, inhibit HBV antigen processing and presentation in APCs. Further, amino acids flanking the viral epitopes in APCs play a critical role in antigen processing. Mutations at these regions in HBV infection harm the proteasomal processing of epitopes and lead to CD8+T-cell escape[30].

HLA genes are critical for the immune system as they control pathogens and clear infections. Host HLA polymorphisms have been demonstrated to influence disease progression in HBV infection[37].Studies found that changes in the surface expression of HLA class I complexes on APCs were associated with HBV replication and persistence. Lower HLA class I expression led to early HBeAg seroconversion, while down-regulation of HLA class II molecules led to pre-core mutants of HBcAg[38].Lumleyet al[30]focused on the interplay between the immune escape of HBV and the selective mutation of HLA-binding residues. They reported that this selective mutation of HLA-binding residues in CD8+epitopes could induce the immune escape of HBV, which is one of the most commonly identified mechanisms for HBV-specific CD8+immune escape[30].

N-linked glycosylation (NLG) is a post-translational modification that can impact the infectivity and antigenicity of HBV. It can mask immune epitopes, leading to immune escape and interfering with the antibody recognition of hepatitis B surface antigen. NLG can also affect the ability through which the envelope protein of HBV interacts with the surface of capsids to drive HBV virion secretion[30].

The connection between TCR on T-cell and HLA class I/peptide complexes induces the activation of CD8+T-cells, but alterations in TCR recognition,i.e., epitope mutations in TCR contact residues, can lead to the immune escape of CD8+T-cells. Immunodominance of HBV epitopes is ensured by the amino acid sequence of the peptide and its concentration and binding affinity with T cell clones. In different CD8+T-cell clones, the same viral peptide can induce different signaling cascades[22]. Figure 2 illustrates the immune escape of HBV, which can occur through multiple pathways. This has a vital role in HBV infection that can last for decades, with some T cell defects being irreversible.

Figure 1 Crosstalk among immune cells and cytokines in hepatitis B virus infection. The complex interactions among immune cells and cytokines in chronic hepatitis B are shown. Hepatitis B virus (HBV)-specific CD8+ T-cells are activated by monocytes and CD4+ T-cells, followed by recruitment and activation of macrophages by active CD8+ T-cells. The activation of natural killer (NK) T-cells is induced by Kupffer cells, which activate NK cells and hepatic stellate cells (HSCs).Suppressive Tregs, Bregs and Kupffer cells induce the functional impairment of CD8+ T cells, CD4+ T-cells and NK cells. Moreover, Treg cells, Kupffer cells and myeloid-derived suppressor cells can lead to the exhaustion of CD8+ T-cells and NK cells. Inflammatory and inhibitory cytokines, including Monocyte chemoattractant protein-1, tumor necrosis factor-α, interferon-γ, interleukin (IL)-4, IL-6, IL-12, IL-13, IL-17, IL-10, and transforming growth factor-β, are involved in the crosstalk among immune cells. The activation of HSCs in sinusoids is induced by a complement protein such as C5a. Finally, decreasing epigenetic modification and function of HBVspecific CD8+ T-cells inhibits the immune control of HBV. PD-1: Programmed death 1; CTLA-4: Cytotoxic T-lymphocyte antigen-4; IL: Interleukin; TNF-α: Tumor necrosis factor-α; TGF-β: Transforming growth factor β; IFN-γ: Interferon-γ; HSC: Hepatic stellate cell; MDSC: Myeloid-derived suppressor cells; NK: Natural killer.

Negative feedback regulation in immune response pathways

Negative feedback regulations commonly occur in immune response pathways. These regulations include negative regulation of immune signal pathways (i.e., negative feedback regulation in TLRs pathway), activation of immune checkpoints, expression of inhibitory cytokines, and activation of inhibitory immune cells. An active innate immunity can induce the secretion of cytokines with antiviral activity, enhance the efficiency of APCs and alter the microenvironment of the liver. However, inflammatory cytokines such as IFNs and tumor necrosis factor-α (TNF-α) can induce immune tolerance[39-41]. Many immune cells and signaling pathways in the liver contribute to immune responses against HBV infection. These immune responses are contact-dependent and can be affected by environmental factors. Inhibitory molecules are produced by hepatic stellate cells, Kupffer cells, T-regulatory cells and myeloid-derived suppressor cells. Through a contact-dependent manner, NK cells can kill HBV-specific CD8+T-cells. Moreover, HBV-specific CD8+T-cells can be suppressed by inhibitory ligands such as programmed death-ligand 1 (Figure 1)[6,42]. However, considering HBV has adaptive and active strategies to evade innate immune responses and negative feedback exists in all immune responses,immune regulator therapy targeting only a single pathway is unlikely to be effective in treating HBV infection.

Host genetic variations associated with HBV infection

Researchers have made great efforts to confirm the associations between HBV infection and host immunogenetics. Host genetic variants, including mutations in TLRs, HLAs, vitamin D-related genes,cytokine and chemokine genes, microRNAs, and HBV receptor sodium taurocholate co-transporting polypeptide, have been observed to impact the outcomes of HBV infection (Table 2)[43-46]. The HLA genes are divided into two classes: HLA-class I (HLA-A, B, C, E, F and G) and HLA-class II (HLA-DP,DQ, DR, DM and DO). Polymorphisms in HLA genes were shown to be significantly associated with thepathogenesis of HBV infection[47,48]. Studies have also reported that the genes encoding cytokines such as interleukins, TNF-α, IFNs and TGF-β, can influence the immune state of CHB patients[49-53]. In a study by Nitschkeet al[54], the authors confirmed that specific HLA class I alleles restricted the efficacy of HBV-specific CD8+T-cells[54], indicating that the host’s immune-related genes can affect the outcome of hepatitis B infection.

Table 2 Host genetic variants associated with hepatitis B virus infection[43-46]

Haplotypes:1G-A-G-A-T-T, rs9277535-rs10484569-rs3128917-rs2281388-rs3117222-rs9380343.2G-G-G-G-T-C, rs9277535-rs10484569-rs3128917-rs2281388-rs3117222-rs9380343.3A-A, rs3077-rs9277535.4A-A, rs2395309-rs9277535.5T-A-T, rs3077-rs9277378-rs3128917.6C-A-T, rs3077-rs9277378-rs3128917.7A-A-C-T, rs2395309-rs3077- rs2301220-rs9277341.8A-A-C-C//A-G-T-G-C-C, rs2395309-rs3077-rs2301220-rs9277341//rs9277535-rs10484569-rs3128917 -rs2281388-rs3117222-rs9380343.9A-A-C-T//A-G-T-G-C-C, rs2395309-rs3077-rs2301220-rs9277341//rs9277535-rs10484569-rs3128917 -rs2281388-rs3117222-rs9380343.10G-G-T-C//A-G-T-G-C-C, rs2395309-rs3077-rs2301220-rs9277341//rs9277535-rs10484569-rs3128917 -rs2281388-rs3117222-rs9380343;11T-T-G-A-T, rs9276370-rs7756516-rs7453920- rs9277535-rs9366816.12T-T-G-G-T, rs9276370-rs7756516-rs7453920-rs9277535-rs9366816.13G-A, rs2856718- rs9275572.14A-G, rs2856718- rs9275572.15A-A, rs2856718- rs9275572.16T-C-C-G-G-G, -1031/-863/-857/-308/-238/-163.17C-A-C-G-G-G, -1031/-863/-857/-308/-238/-163.18A-T-G-T-T-T-T-C-T, +88344/+102906/+103432/+103437/+103461/+104261/+104802/+106151/+106318.19T-C, rs12375841-rs17803780.20C-A-C, rs421446-rs107822-rs213210.21T-G-T, rs421446-rs107822-rs213210.22C-A-C-C-G, -1722/-1661/-658/-319/+49.23T/C-A-C-C-G, -1722/-1661/-658/-319/+49.24T-A-C-C-A, -1722/-1661/-658/-319/+49.25A-T-A, rs17401966-rs12734551-rs3748578.26C-C, rs111033850-rs12953258.27T-T-C-T-A, -1800/-1627/+4645/+5806/+6139.28C-T-C-T-T, rs8179673-rs7574865-rs4274624-rs11889341-rs10168266.29G-G-A, rs3757328-rs6940552-rs9261204.SNPs/Hap/CNVs: Single nucleotide polymorphisms/Haplotype/Copy number variations; HLA: Human leukocyte antigen; TLR: Toll-like receptors.

Figure 2 Mechanism of immune escape in antigen-presenting cell/hepatitis B virus special T-cell. Hepatitis B virus (HBV)-infected hepatocytes produce various HBV antigens that are swallowed and digested by antigen-presenting cells (APCs), producing HBV peptide/human leukocyte antigen (HLA)complexes. Antigen processing escape mutants, down-regulating HLA expression and mutation of HLA binding residues may appear in APCs. The HBV peptide/HLA complexes are transferred to the surface of APC and make contact with T-cell receptor (TCR) on the surface of CD8+ T-cells. Masking HLA/TCT binding residues with N-linked glycosylation and mutation of TCR binding residues influences TCR affinity/avidity, leading to CD8+ T-cell stimulation or inhibition. The square icon displays:(1) Increase in viral antigen; (2) Antigen processing escape mutants; (3) Down-regulation of HLA expression; (4) Mutation of HLA binding residues; (5) Masking of HLA/TCT binging residues with N-linked glycosylation; (6) Mutation of TCR binding residues; (7) Stimulation induced by cytokine production and cytolytic activity; and(8) Inhibition caused by exhaustion, anergy and tolerance. HBV: Hepatitis B virus; TCR: T-cell receptor; HLA: Human leukocyte antigen.

Researchers have observed significant differences in HBV infection rates between Western and East/Southeast Asian populations. Prior to HBV vaccination programs, the prevalence of HBsAg was less than 1% in the Caucasian population but higher than 10% in the Chinese population[43]. This difference was investigated in several studies, which showed that HLA molecules in European,Caucasian, Middle East, African-American and Asian populations affected the rate of HBV infection[43,55,56]. In addition, discordances in HBV-specific CD8+T-cell repertoires observed in different races, i.e.,between Chinese and Caucasian populations, could be related to race-dependent HLA gene variants,leading to the different T-cell responses observed between different populations and ethnicities[57].

Thus, these findings underline the complexity of HBV-specific immune control efficacy, which is influenced by HBV components, negative feedback regulation in immunity and host genetic variants(Figure 3).

Heterogeneity of immune control in HBV infection

Figure 3 Interplay between hepatitis B virus-specific immune control, hepatitis B virus components, and negative feedback regulation in immunity and host genes. HBV: Hepatitis B virus.

Heimet al[6]reviewed the heterogeneity of HBV-specific CD8+T-cells and described the functional deficiencies and distinct phenotypical characteristics associated with HBV-specific CD8+T-cells exhaustion. T-cell impairment demonstrates hierarchical and progressive loss in antiviral functions,from functional suppression to physical deletion in T-cells, which depend on the quantity of HBV antigens and the duration of T cell exposure to these antigens[31,58]. Moreover, exhausted CD8+T-cells do not represent a homogeneous T-cell population but are rather heterogeneous in function and phenotype. Kuiperyet al[5]proposed concepts related to the heterogeneity of immune responses in CHB patients[5]. Based on reports from literature, we summarized the following concepts to improve our understanding on the heterogeneity of immune control.

Figure 1 illustrates the activation and inhibition of immune signaling pathways that overlap in HBV infection, multiple immune cell populations and integrated signals pathways that simultaneously respond to the stimulation of HBV components, and the ability of HBV-specific immune control depends on the overall immune responses of an individual rather than the capability of single immune cells or a single immune pathway.

Based on the immune escape mechanisms of APCs/CD8+T-cells presented in Figure 2, the heterogeneous immune responses of T-cells are related to very fine mechanisms of immune regulation that influence the immune control of HBV-specific T-cells, or T-cells sensitivity/inhibition.

Figure 3 outlines the reasons for heterogeneous immune control. The overall immune control against HBV in an individual is influenced by HBV, negative feedback regulation in the immune signaling network and host genetic variants. Therefore, any changes in these three countenances could lead to fluctuations affecting the effectiveness of immune control. Thus, CHB infection is divided into four clinical phases: Immune tolerant with HBeAg-positive, HBeAg-positive immune-activation, inactive carrier with HBeAg-negative, and HBeAg-negative immune-activation. Further, heterogeneous immune controls can lead to different clinic phases and disease outcomes such as acute hepatitis, chronic hepatitis, cirrhosis, hepatocellular carcinoma and hepatic failure[43].

Reports have shown that host genetic polymorphisms are crucial determinants influencing HBV infectious rate and disease outcomes in Caucasian, Saudi Arabian, African-American, European, and Asian populations[56,59,60]. In addition, the host genetic variants of individuals from the same race can influence disease outcomes and the efficacies of antiviral therapy.

Researcher and immunologists who often overlook immune compartmentalization should be cautious when interpreting findings from the peripheral blood of patients.

IFN-α TREATMENT FOR CHB

Definition of partial cure and functional cure

A complete cure from HBV infection is currently hypothesized to be possible if the cccDNA and integrated HBV DNA are eliminated from hepatocytes. However, this is challenging as cccDNA can still persist in patients despite spontaneous recovery from an acute HBV infection. Since 2017, some advances in CHB therapeutics have been achieved[61], and researchers have proposed new definitions of cure. For instance, a partial cure has been defined as persistently undetectable HBV DNA and HBeAg in patients’ serum after the completion of a limited course of antiviral therapy. Functional cure has been defined as sustained and undetectable HBV DNA and HBsAg in patients’ serum, with or without seroconversion to hepatitis B surface antibody (anti-HBs), after a limited course of therapy. Complete sterilizing cure has been defined by the absence of HBsAg and eradication of HBV DNA, including HBV virion, integrated HBV DNA and cccDNA in the liver and serum of patients. However, because current treatments cannot deliver complete sterilizing cure, functional cure is the selected goal of therapy.

NAs and immunotherapy

Therapeutic strategies for CHB can be classified into two categories: NAs targeting HBV replication and immune modulators targeting immune control. NAs can cause rapid decay of HBV DNA in the peripheral blood but cannot completely eradicate HBsAg from patients' serum and cccDNA in hepatocytes[62,63]. Even though the virus might be undetectable in the serum after long-term treatment with NAs, low-level viral replication still persists due to the conservation of cccDNA in the nucleus of hepatocytes. Thus, prolonged NAs treatments are rarely associated with CHB cure and inevitably result in either NAs resistance or viral relapse[62-66].

In contrast, immunotherapy can target the innate and adaptive immunity to reinvigorate the host immune response to long-term inhibition of viral replication. Therapeutic strategies involving innate immunity include activating pattern recognition receptors (i.e., TLRs and RIG-I), enhancing cytokine secretion, and improving the efficacy of NK cells. For adaptive immunity, therapies are directed at restoring the effects of HBV-specific T-cells and B-cells. Clinically, although immunotherapy can lead to sustained HBsAg loss, it cannot eradicate cccDNA from hepatocytes. Thus, being the more promising treatment compared to NAs, the ultimate goal of immunotherapy is currently targeted at achieving functional cure, enabling spontaneous control of HBV replication and maintaining disease remission without antiviral therapy[3]. Hoogeveen and Boonstra[32]reported that immunomodulators regulating a single immune pathway might not restore antiviral immunity as multiple immune pathways in the host enhance specific HBV immune responses[32].

Mechanism and clinical application of IFN-α therapy

IFNs are produced and released by immune cells in response to HBV components[67,68]. Of the known IFNs, IFN-α has broad-spectrum effects on viruses and tumors, and contributes to immune regulation by suppressing viral replication and cell growth. The antiviral function of IFN-α is cascaded by binding to IFN receptors on immune cells, activating signal transcription pathways, and inducing ISGs expression and related product secretion. Various ISGs products were found to inhibit different stages of the viral life cycle[69]. Further, epigenetics was shown to play a critical role in regulating cccDNA transcription[70-73]. IFN-α can regulate the epigenetic repression of cccDNA transcription by inducing cccDNA-bound histone hypo-acetylation and increasing the recruitment of transcription co-repressor on cccDNA[63,65,73]. In addition, IFN-α can upregulate HLAs expression to activate innate and adaptive immune responses. Many researchers have investigated the host genes associated with IFN-α treatment outcomes and observed its genetic polymorphisms[43,44,74-78](Table 3).

As described earlier, due to negative feedback mechanisms, immune modulators targeting a single signal pathway might not improve the overall and long-term immune responses[61]. In this regard, the advantages of IFN-α treatment are that IFN-α can simultaneously affect multiple immune pathways and various immune cell populations in the host and integrate signals to improve the efficacy of immune control[10,11,15,36]. Currently, only IFN-α treatment was found to improve the efficacy of immune control[64,65].

IFN-α has been approved for the treatment of hepatitis B for over 20 years[36,61,65]. Compared with NAs, IFN-α has shown better efficacy in HBeAg seroconversion and HBsAg loss, with no risk of drug resistance[79]. For groups of patients with good prognoses, such as Caucasians, young age, low viral load, and females, IFN-α treatment has been more effective[80,81]. One study reported functional cure in 10%-20% of Caucasians who underwent IFN-α treatment, while it was < 5% in Asian patients[82].However, most of the underlying mechanisms of IFN-α therapy are still unclear. More research is needed to investigate these significant differences in IFN-α efficacy between different groups of patients.

Table 3 Host genetic variants associated with interferon-α therapy[43,44,74-78,91]

IMPROVEMENT OF HBV-SPECIFIC IMMUNE CONTROL BY IFN-α RETREATMENT

IFN-α retreatment

In 1996, although IFN-α was already being used to treat CHB patients, only 20%-30% of the patients achieved viral suppression or partial cure with single IFN-α treatment. Then, it was found that IFN-α retreatment in these remaining patients could enhance treatment outcomes. Thus, multiple courses of IFN-α were implemented to treat these patients and researchers observed that three courses of IFN-α treatment were effective in treating HBeAg positive or negative patients. With multiple frequencies of IFN-α treatment, partial or functional cure rates gradually increased to approximately 25%-40% but were mostly observed in patients of white race[10-14](Table 4).

By 2008, failures from combination therapy with nucleoside and nucleotide were reported, and multidrug resistance with NAs treatment started to increase in China. Comparatively, IFN-α retreatment was associated with safe stopping of NAs administration and induced better-sustained responses to IFN-α[15]. Thus, when researchers started to investigate the effects of increasing the frequency and extending the total course of IFN-α treatment and found that these could significantly improve the rate of functional cure in Asian and Caucasian patients[73-75,80-83]. IFN-α retreatment was recommended by the Asian-Pacific clinical practice guidelines[16-18]and by Yinet al[64](Table 4). Based on these promising findings and recommendations, we estimate that more CHB patients in Asia would receive IFN-α retreatment and experience better antiviral efficacy.

Interplay between IFN-α retreatment and the HBV-specific immune control

Recently, more and more HBV-specific immune mechanisms have been discovered, inspiring clinicians and immunologists to collaborate to study the interplay between immune mechanisms and clinical events in hepatitis B. Changet al[84]summarized the relationship between hepatitis flare and immune responses in CHB patients to explore the underlying immune mechanism of hepatitis flares[84]. The observations made from the strategy of Chang'set al[84]involved in IFN-α retreatment.

Table 4 Summary and timeline of interferon-α retreatment for chronic hepatitis B virus infection

Asymptomatic persistence of cccDNA in the liver of patients who had acute hepatitis B or selflimiting HBV infection, despite the resolution of HBV infection[3], indicates that the host’s immune system can fully inhibit HBV replication and that the specific HBV immune control in these individuals had an overwhelming advantage over HBV replication. In addition, investigations on the heterogeneous immune control of HBV infection have shown that the heterogeneity depends on the interplay between the host, virus and therapy, including host genes and immunity state, HBV load, duration of HBV infection, and IFN-α treatment and course of treatment[5,6,31,58]. However, the exact mechanismviawhich IFN-α retreatment exerts its benefits is yet to be fully elucidated.

Apart from HBV load, HBsAg and HBeAg, markers associated with the immune control of IFN-α treatment are lacking. In a study by Konerman and Lok[79], the authors proposed a scoring system that could help assess the efficacy of immune control[79]. The type of immune control could be estimated from a patient’s HBV DNA, HBeAg seroconversion, HBsAg loss and times of IFN-α treatment, based on the following criteria: (1) Patients with acute hepatitis B or self-limiting HBV infection could achieve automatic cure without IFN-α treatment; (2) Patients with acute hepatitis B could achieve functional cure with one time IFN-α treatment; (3) CHB patients with one time IFN-α treatment could achieve functional cure; (4) CHB patients with one time IFN-α treatment could achieve partial cure; (5) CHB patients with multiple times of IFN-α treatment could achieve functional cure; and (6) CHB patients with multiple times of IFN-α treatment could achieve partial cure. These criteria suggest a step-like decline in immune control with increasing infection severity.

Clinical studies have confirmed that IFN-α retreatment could gradually increase the rate of partial and functional cure (Table 4)[10,11,13,15,36]and that CHB patients often have diverse HBV-specific immune control. Since 2016, researchers in China have reported numerous findings from clinical trials in which patients with inactive HBsAg carriers or low-level viremia were selectively enrolled and treated with IFN-α to evaluate their functional cure rate[85-88]. However, it should be noted that these were performed under trial settings because clinical guidelines do not recommend IFN-α therapy for the treatment of CHB in these patients[16,89,90]. A high rate of functional cure, 44.7%-84.2% of HBsAg loss and 20.2%-68.2% of HBsAg seroconversion were reported, in which a distinctive pattern of immune control whereby a close correlation between lower HBsAg at baseline and higher rates of HBsAg loss or HBsAg seroconversion was observed[85-88]. This pattern also appeared in the final course of IFN-α retreatment in previous studies[10,11,13,15,36], indicating that reducing HBsAg could be a prerequisite for achieving functional cure during IFN-α retreatment.

Taken together, current literature indicates that IFN-α retreatment could gradually enhance the overall immune control and improve the antiviral efficacy of IFN-α in CHB patients (Figure 4).

Figure 4 Interferon-α retreatment improves the efficacy of hepatitis B virus-specific immune control. Interferon-α (IFN-α) retreatment can lead to various treatment outcomes, namely no response, hepatitis B virus (HBV) decline, partial cure and functional cure. Multiple frequencies of IFN-α treatment can potentially restore specific immune control to HBV infection and simultaneously increase the rate of partial cure and functional cure. A: Exhausted immune control to HBV before IFN-α therapy (Baseline); B: Without HBV decline following IFN-α therapy; C: HBV decline; D: Partial cure; E: Functional cure. CHB: Chronic hepatitis B.

CONCLUSION

The interactions between immune cells and cytokines form a complex immune response network that exerts immune control over HBV infection. The efficacy of HBV-specific immune control is affected by HBV components, negative feedback regulation in the immune system, host genetic variants, and heterogeneity in the function and phenotype of immune control to HBV. Treatment with IFN-α can simultaneously affect multiple immune pathways and various immune cell populations in the host and integrate signals to improve the efficacy of immune control. Clinically, increasing the frequency and extending the total course of IFN-α retreatment have improved functional cure rates, indicating that IFN-α retreatment could gradually enhance the overall immune control. Further research on IFN-α retreatment could help promote this strategy in CHB patients with.

Altogether, this article outlined immune control without detailed discussions on immunity-related markers during immune transformation. In future studies, the discovery of detailed markers associated with immune transformation could provide important clues in understanding the underlying mechanism of immune control to improve the treatment of HBV infection.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We are very grateful to Prof. Gao-Jun Teng in Zhong-Da Hospital, Southeast University and Prof. Bei Zhong in the sixth Affiliated Hospital of Guangzhou medical University/Qingyuan People’s Hospital for the comprehensive evaluation of the manuscript and valuable advices. Authors acknowledge Dr.Cun Shan in the Department of infectious disease, Nanjing Zhong-Da Hospital for data collection.

FOOTNOTES

Author contributions:All authors contributed to the study conception and design; The first draft of the manuscript was written by Yin GQ; All authors commented on previous versions of the manuscript, they all read and approved the final manuscript.

Conflict-of-interest statement:All the authors report no relevant conflicts of interest for this article.

Open-Access:This article is an open-access article that was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution NonCommercial (CC BYNC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is noncommercial. See: https://creativecommons.org/Licenses/by-nc/4.0/

Country/Territory of origin:China

ORCID number:Guo-Qing Yin 0000-0002-8972-3752; Ke-Ping Chen 0000-0002-8601-7481; Xiao-Chun Gu 0000-0002-7289-8054.

S-Editor:Fan JR

L-Editor:A

P-Editor:Fan JR

World Journal of Gastroenterology2022年40期

World Journal of Gastroenterology2022年40期

- World Journal of Gastroenterology的其它文章

- Expression of the methylcytosine dioxygenase ten-eleven translocation-2 and connexin 43 in inflammatory bowel disease and colorectal cancer

- Liver transplantation is beneficial regardless of cirrhosis stage or acute-on-chronic liver failure grade: A single-center experience

- Curcumin alleviates experimental colitis via a potential mechanism involving memory B cells and Bcl-6-Syk-BLNK signaling

- Pancreatic acinar cell carcinoma: A comprehensive review

- Management of liver diseases: Current perspectives

- Improving the prognosis before and after liver transplantation: Is muscle a game changer?