转录因子调控青蒿素生物合成的作用机制研究进展

詹忠根

转录因子调控青蒿素生物合成的作用机制研究进展

詹忠根

浙江经贸职业技术学院生物制药教研室,浙江 杭州 310018

青蒿素是从药用植物黄花蒿中分离的一种倍半萜内酯,广泛应用于疟疾治疗,野生资源含量较低。为缓解持续增加的需求,尝试提高青蒿素含量或产量的研究成为热点课题。转录因子具有调节代谢途径中一个或多个基因表达的作用,据报道,已有多个转录因子家族参与调节青蒿素的生物合成和积累,干预转录因子表达是提高青蒿素含量或产量的重要手段。从转录因子调控黄花蒿腺毛形成与发育和转录因子调控青蒿素生物合成2个方面综述青蒿素的生物合成机制,以期为青蒿素代谢的转录调控研究提供参考。

青蒿素;转录因子;生物合成;腺毛发育;激素信号;光信号;逆境胁迫

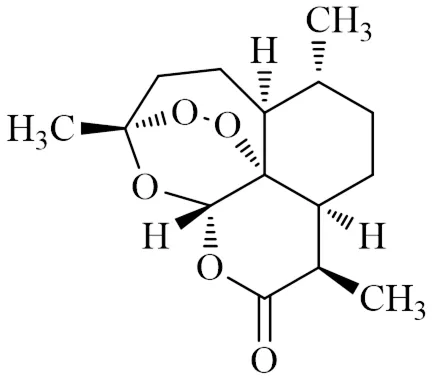

青蒿素是从药用植物黄花蒿L.中分离的一种含有“过氧桥”结构(1,2,4-三烷环)的倍半萜内酯(图1),广泛应用于疟疾治疗。全球每年新增疟疾病例连续多年超过2亿,加之青蒿素及其衍生物还具有抗病毒、抗肿瘤、抗炎、抗氧化及治疗糖尿病、肺结核等潜力,致使其国际需求持续增加[1-2]。但青蒿素仅分布于黄花蒿叶片、芽和花表面的分泌性腺毛(glandular secretory trichomes,GSTs),野生资源含量较低(占植物干质量的0.1%~1.0%)且不稳定[3]。为缓解日益突出的供需矛盾,近年来尝试了多种方法试图提高青蒿素的含量或产量,如成功培育青蒿素含量超过2%(干质量)的高产品种[4],利用酵母工程菌半合成青蒿素初步达到可商业化的工艺水平[5],抑制竞争代谢途径关键酶(鲨烯合成酶)基因获得青蒿素质量分数为31.4 mg/g的高产转基因植株[6],过表达青蒿素生物合成关键酶基因或转录因子基因使青蒿素含量成倍增加[7-8],以及利用异源宿主[9]或黄花蒿自交系非GSTs细胞合成青蒿素[10]等研究为提高青蒿素产量做出了有益探索。

图1 青蒿素的化学结构

尽管上述研究未能从根本上解决青蒿素供应不足或有效降低青蒿素生产成本的难题,却为人们深入了解青蒿素生物合成及其调控机制提供了很好的帮助。目前,青蒿素生物合成途径已基本明确[11],黄花蒿基因组测序也已完成[12],但要进一步提高青蒿素生物合成能力仍缺乏良好的遗传转化体系,通过串联表达等技术靶向生产青蒿素将同时面临鉴定大量结构基因和转化效率低等困难。青蒿素生物合成基因的时空表达受不同转录因子的严格调控,随着青蒿素生物合成过程的基本阐明,科学工作者更加注重青蒿素生物合成相关的转录因子研究并取得长足进展。因此,本文从转录因子调控黄花蒿腺毛形成与发育和转录因子调控青蒿素生物合成2个方面综述其调控青蒿素生物合成的作用机制,以期为青蒿素代谢的转录调控研究提供参考。

1 黄花蒿转录因子研究概况

由于基因扩张,黄花蒿中的转录因子数量众多,基因组中发现2717个,尤其是香豆酸-3-羟化酶(p-coumarate 3-hydroxylase,C3H)、远红色受损应答1(far-red impaired response 1,FAR1)和根瘤起始类蛋白(nodule inception-like protein,NLP)3个转录因子家族数量远超其他物种[12],转录组中检测到55个家族的1588个转录因子,其中乙烯响应因子(ethylene resposive factor,ERF)家族成员最多,达123个,且碱性螺旋-环-螺旋转录因子(basic helix-loop-helix transcription factors,bHLH)、C2H2锌指结构转录因子(Cys2/His2-type zinc finger protein,C2H2)、NAC转录因子(NAM-ATAF1/2-CUC2,NAC)、C3H、WRKYGQK结构域锌指型转录因子(WRKYGQK domain zincfinger motif,WRKY)、MYB转录因子、碱性亮氨酸拉链转录因子(basic leucine zipper,bZIP)和GRAS转录因子家族成员也超60个[13]。由于转录因子能有效调节植物次生代谢的生物合成,为厘清青蒿素生物合成转录调控网络,近年来基于基因组数据[12]、转录组测序[13]、文库筛选[14]相继发现AP2/ERF、bHLH、MYB、NAC、WRKY和bZIP等多个转录因子家族成员参与青蒿素的生物合成调控。如Shen等[12]应用热力图从黄花蒿全基因组数据中鉴定了15个调控青蒿素生物合成的转录因子,Hao等[13]发现ERF、MYB、bHLH、HD-ZIP、赖氨酸特异性组蛋白去甲基化酶(lysine specific demethylase,LSD)和E2F/DP家族成员介导光照下茉莉酸(jasmonate,JA)处理的青蒿素生物合成,Pan等[15]用基因芯片检测到WRKY家族成员AaWRKY11、AaWRKY14参与UV-B辐照处理后的青蒿素生物合成,在光与赤霉素(gibberellins,GA)协同提升青蒿素生物合成的研究中发现、、、、等179个转录因子基因与紫穗槐二烯合成酶(amorpha-4,11-diene synthase,)基因共表达,、、、等161转录因子基因与细胞色素P450依赖性羟化酶基因(cytochrome P450 monooxygenase,)共表达[16]。此外,还对AaMYB1[17]等近40个转录因子的调控功能进行了较为详尽的研究(表1),为揭示转录因子调控青蒿素生物合成机制及利用基因工程技术提高青蒿素含量打下了坚实的研究基础。

表1 青蒿素生物合成相关转录因子

Table 1 Transcription factors of artemisinin biosynthesis

类型转录因子名称功能文献 MYBAaMYB1可激活腺毛形成必需基因GL1、GL2表达及GA4合成与降解,共同促进GSTs形成,促进CYP71AV1、ADS基因表达17 AaMYB2AaMYB2过表达植株中,AaHD1、AaMYB1、CYP71AV1基因表达量下降,腺毛密度降低18 AaMYB4响应UVB辐照,正调控ADS、DBR2基因表达19 AaMYB5/AaMYB16AaMYB5响应JA刺激,抑制腺毛形成,形成AaHD1-AaMYB5复合体调控AaGSW2转录因子;AaMYB16促进腺毛形成,形成AaHD1-AaMYB16复合体调控AaGSW2转录因子20 AaMYB15响应暗处理和JA刺激,负调控ADS、CYP71AV1、DBR2、ALDH1和AaORA基因表达21 AaMYB17正调控GSTs形成22 AaMIXTA1通过促进角质层、蜡质形成,进而正调控腺毛发育23

续表1

HD1-同源结构域蛋白1 GSW2- GST-特异性WRKY转录因子 TLR1/TLR2-腺毛负调节因子1/2 TAR2-腺毛和青蒿素调节因子2 HY5-下胚轴伸长转录因子 TGA-TGACG基序结合因子 PIFs-光敏色素互作因子 MYC2-骨髓细胞组织增生因子2 EIN3/EIL-乙烯不敏感因子3/乙烯不敏感样因子3 MeJA-茉莉酸甲酯 ABA-脱落酸 SA-水杨酸

HD1-homeodomain protein 1 GSW2- GST-specific WRKY transcription factor TLR1/TLR2-trichomeless regulator 1/2 TAR2-trichome and artemisinin regulator 2 HY5-elongated hypocotyl 5 TGA-TGACG motif-binding factor PIFs-phytochrome interacting factors MYC2-myelocytomatosis 2 EIN3/EIL-ethylene-insensitive 3/EIN3-like MeJA-methyl jasmonate ABA-abscisic acid SA-salicylic acid

2 转录因子调控黄花蒿腺毛形成与发育

黄花蒿叶片、芽和花表面存在2种多细胞头状腺毛,即GSTs和T型非分泌性腺毛(T-shaped non-glandular trichomes,TNGs)。GSTs由10个细胞(2个基细胞、2个颈细胞、4个近顶细胞和2个顶细胞)及1个储存青蒿素的皮下空间组成,是青蒿素生物合成的主要场所,ADS、CYP71AV1、青蒿素醛Δ11(13)还原酶2(double bond reductase 2,DBR2)和醛脱氢酶1(aldehyde dehydrogenase 1,ALDH1)等青蒿素生物合成关键酶及大量转录因子基因在GSTs的顶细胞和近顶细胞中表达[14,53]。因此,GSTs数量越多(或密度越高),生物合成能力越强,意味着青蒿素含量越高。然而,GSTs仅占植株干质量的2%且易于脱落,以及在GSTs中合成的其他萜类与青蒿素合成存在代谢竞争等因素极大阻碍了青蒿素产量的提升,通过转录因子促进GSTs形成、改善GSTs生长发育状态是提升药材整体品质的有效策略[10,54]。

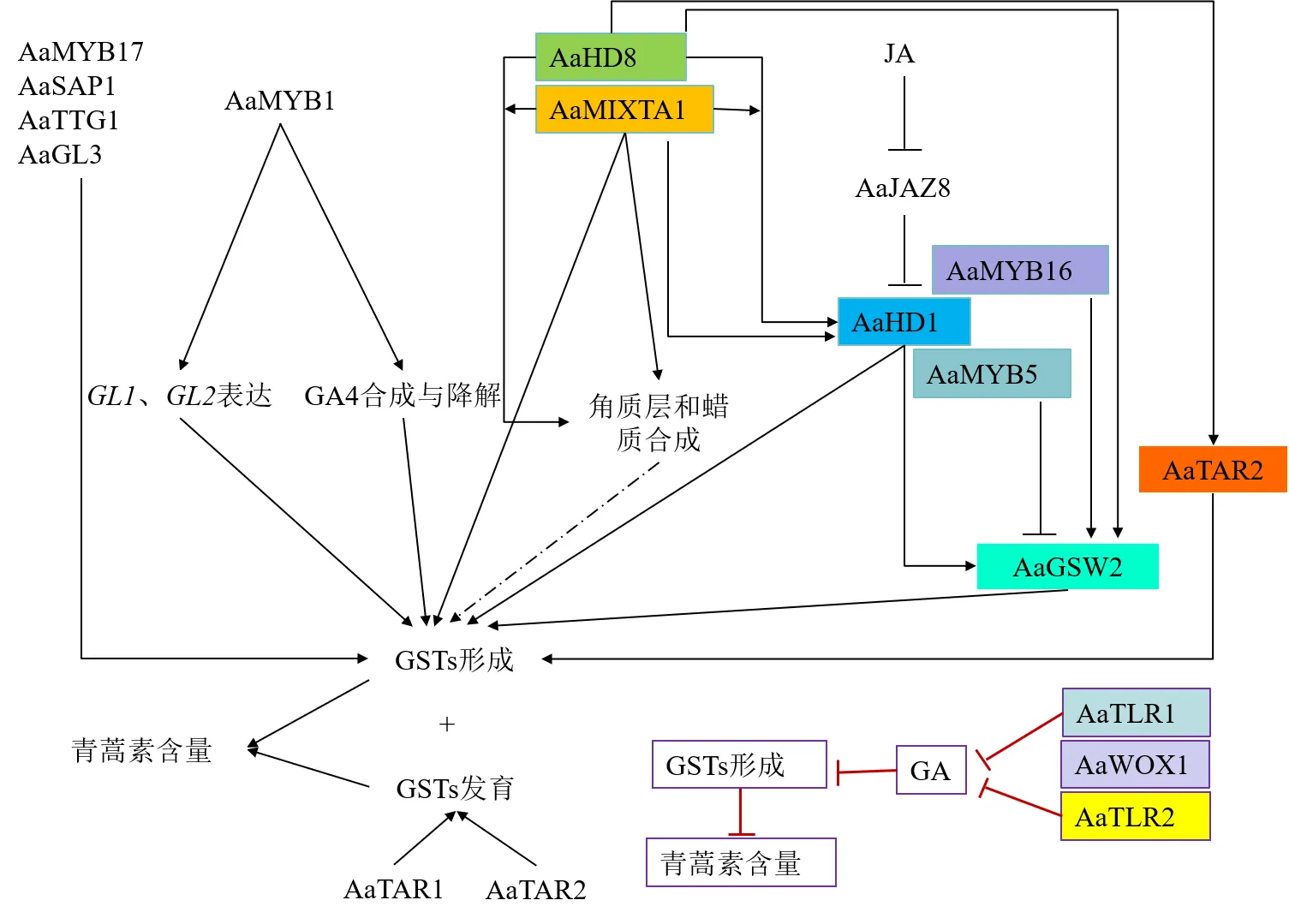

研究表明,R2R3-MYB和HD-ZIP IV类转录因子在GSTs的形成与发育中扮演重要角色(图2)。AaMYB1是第1个从黄花蒿腺毛特异性EST文库中分离的腺毛形成相关转录因子,位于R2R3-MYB亚家族S13亚组,编码330 aa,在黄花蒿叶片成熟时表达上调并持续到花蕾形成。过表达可激活腺毛形成必需基因表达及GA4合成与降解,共同促进GSTs形成[17]。AaMYB2能与拟南芥腺毛调控复合体蛋白GL3直接作用,过表达的植株中、、基因表达量下降,腺毛密度降低。主要在GSTs基细胞中表达的R2R3-MYB S9亚组转录因子AaMIXTA1促进黄花蒿GSTs和TNGs密度增加可能与其正调控角质层、蜡质形成有关。过表达AaMIXTA1、RNA干扰和双荧光素酶报告基因检测均显示AaMIXTA1正调控角质层形成基因、和蜡质形成基因、、表达[23]。而与AaMIXTA1同源的转录因子AaMYB17,主要在芽尖等分生组织的GSTs特异表达,其正调控GSTs形成的作用机制与AaMIXTA1有所差异,并非通过调控角质层生物合成基因表达发挥作用[22]。研究发现,另一R2R3-MYB转录因子AaTLR1在AaWOX1介导下与LFY转录因子AaTLR2结合,通过抑制GA合成,下调腺毛形成正调控转录因子、和基因表达等负调控GSTs形成,并下调、、、基因表达进一步抑制青蒿素生物合成[24]。

除R2R3-MYB外,2种HD-ZIP IV转录因子AaHD1、AaHD8调控腺毛形成的机制研究较为详尽,两者既可单独发挥作用,也可通过相互作用增强活性或共同调控其他转录因子活性,促进腺毛形成。在外源JA刺激下,AaHD1与抑制蛋白AaJAZ8分离,释放出的AaHD1促进GSTs和TNGs形成,敲除基因,JA促进腺毛形成的作用下降[26],而AaHD8可通过激活角质层生物合成关键酶基因表达间接促进腺毛形成[25]。同时,位于上游的AaHD8可与AaHD1启动子L1-box(TAAATGC/TA)结合,增强AaHD1的调控活性或与AaMIXTA1形成复合体,协同增强对角质层形成及AaHD1的调控效果[27],此外,AaHD1、AaHD8还可分别调控AaGSW2、AaTAR2转录因子的活性,促进GSTs形成[25,33]。而2个调控作用相反且相互竞争的转录因子AaMYB5、AaMYB16则很大程度依赖与AaHD1的START-SAD结构域结合,才能发挥对AaGSW2转录因子的调控作用[20]。由于HD-ZIP转录因子通常以二聚体形式发挥调控作用,深入研究AaHD1/AaHD8的相互作用机制有助于揭示调控腺毛形成的特异性调节因子。

图2 转录因子通过调控GSTs形成与发育对青蒿素产量的影响

与前述转录因子调控功能不同,AP2/ERF转录因子AaTAR1和S15亚组的MYB转录因子AaTAR2调控的是腺毛发育过程而不是腺毛形成。在TAR1-RNAi植株中,GSTs顶部细胞膨胀、GSTs细胞数量减少、表皮蜡质异常沉积和角质层渗透性发生改变[34]。抑制基因表达,GSTs和TNGs 2种腺毛形态发生剧烈变化,腺毛细胞皱缩,缺乏支持,但过表达基因对腺毛形态和密度无明显影响[25]。此外,也有报道锌指蛋白AaSAP1和WRKY转录因子AaTTG1、AaGL3能响应JA诱导,正调控腺毛的发育,提高腺毛密度,但具体机制还有待进一步解析[55-56]。

通常认为,TNGs与GSTs的主要区别是其不具有分泌和贮存各种次生代谢物的能力,但随着TNGs青蒿素合成能力的证明[10],以及多种转录因子(如AaHD1、AaHD8、AaMIXTA1、AaTAR2等)同时调控GSTs和TNGs的形成,表明2种腺毛的形成至少在早期阶段可能具有相同或相似的分子机制,为进一步开发非GSTs资源合成青蒿素的研究提供了有力的理论依据。

3 转录因子调控青蒿素生物合成

3.1 调控青蒿素生物合成关键酶基因表达

以法尼基焦磷酸(famesyl diphosphate,FPP)合成为分界点,青蒿素生物合成可分为上游步骤和下游步骤2个阶段(图3)。青蒿素生物合成上游步骤已比较清楚,有较为公认的限速酶和酶促反应。其中,甲羟戊酸(mevalonate acid,MVA)途径是FPP合成的主要贡献者,阻断MVA途径青蒿素含量降低80.4%,而阻断2-甲基赤藓醇磷酸(methylerythritol phosphate,MEP)途径青蒿素含量仅降低14.2%[57]。进一步研究表明,MEP途径关键酶基因仅在含有叶绿体的GSTs近顶细胞中表达[58]。FPP合成时,由MEP途径提供1分子异戊烯基焦磷酸(isopentenyl diphosphate,IPP)先与MVA途径生成的1分子二甲基烯丙基焦磷酸(dimethylallyl pyrophosphate,DMAPP)合成牻牛儿基二磷酸(geranyl diphosphate,GPP),然后转运至顶细胞与胞质中MVA途径提供的1分子IPP形成通用前体FPP[59]。在下游步骤,FPP先被ADS催化生成紫穗槐二烯(amorpha-4,11-diene,AD),再经CYP71AV1催化依次生成青蒿醇、青蒿醛和青蒿酸[60-62]。值得注意的是,青蒿醛既可在DBR2、ALDH1催化下形成二氢青蒿醛、二氢青蒿酸,并最终生成青蒿素[63-64],也可被ALDH1、CYP71AV1催化生成青蒿酸而最终形成青蒿素B[62,65]。可见,DBR2酶的活性对于青蒿醛是否被DBR2有效催化形成二氢青蒿醛至关重要,是能否得到高含量青蒿素的关键。另外,青蒿醇也可形成其他中间产物参与青蒿素合成,如青蒿醇可被催化形成二氢青蒿醇[63],再被CYP71AV1和ALDH1催化形成二氢青蒿醛[二氢青蒿醛也可被二氢青蒿醛还原酶1(dihydroartemisinic aldehyde reductase 1,RED1)还原成二氢青蒿醇],参与青蒿素合成[66-67]。但下游步骤仍存在一些争议之处:如有研究认为青蒿酸可经青蒿素B和青蒿烯进而形成青蒿素[68],而前体饲喂研究表明二氢青蒿酸才是青蒿素的直接前体,青蒿酸并不能转化为二氢青蒿酸和青蒿素,其主要代谢产物是青蒿素B[60,65]。再如,尽管有研究证明二氢青蒿酸转化成青蒿素及青蒿酸转化成青蒿素B的过程是一种自发的光氧化反应,而非酶促反应[69],但也有研究认为,青蒿素含有过氧桥键,可能存在一种过氧化物酶或其他一系列氧化酶催化二氢青蒿酸转化成青蒿素[70]。现已证明,过氧化物酶在黄花蒿无细胞系系统中间接参与向青蒿素的生物转化[71],并发现3种与青蒿素含量相关的过氧化物酶[72-74],如果能分离出相应的酶,将极大促进青蒿素的合成生物学研究。

图3显示多种限速酶控制着青蒿素的合成进程,这些酶的基因表达水平受转录因子严格调控,迄今已报道AP2/ERF、bHLH、MYB、NAC、WRKY、bZIP、HD-ZIP IV、TCP、SPL、YABBY等家族的众多转录因子具有调控青蒿素生物合成关键酶基因、表达的作用。由于这些基因的启动子区域含有多种转录因子结合位点,如AP2/ERF结合位点RAA基序、WRKY结合位点W-Box、bZIP结合位点ABRE基序、MYB结合位点E-Box、bHLH结合位点G-box[75],因此,在已有研究中,大部分转录因子能与相应位点特异性结合,激活基因表达,直接正调控青蒿素生物合成。如最近发现AaWRKY17和AabZIP9能与ADS启动子W-box基序、“ACGT”顺式作用元件结合,上调基因表达,过表达植株中青蒿素、双氢青蒿素和青蒿酸含量分别提高23.2%~67.1%、34.5%~92.8%、40.4%~121.2%[30,38]。AaSPL2能与启动子的GTAC-bow基序结合,调控基因转录,过表达植株中青蒿素含量提高33%~86%[49]。AaYABBY5能直接与、启动子结合,或以其他方式间接上调、基因表达,过表达植株中双氢青蒿素和青蒿素含量显著提高[50]。同时也有部分转录因子通过与其他转录因子相互作用而间接正调控青蒿素生物合成,如AaMYB2和bHLH类转录因子AaPIF3对基因表达均有促进作用,过表达AaPIF3,青蒿素含量提高55.97%~65.21%[12,42],但AaPIF3只能通过AaERF1起间接调控作用[76];乙烯信号关键因子AaEIN3通过促进叶片衰老基因表达,加速黄花蒿叶片衰老,进而减弱、、和基因表达,降低青蒿素积累[51]。还有一些转录因子(如AaMYB15)作为负调控因子参与青蒿素生物合成[21]。此外,AaWRKY40、AaPWA73483、AaPWA66309等多个转录因子的调控机制也在继续研究之中[31]。

G3P-甘油醛-3-磷酸酯 HMGS-3-羟基-3-甲基戊二酸单酰辅酶A合酶 HMGR-3-羟基-3甲基-戊二酸单酰辅酶A还原酶 DXS-1-脱氧-D-木酮糖-5-磷酸合成酶 DXR-1-脱氧-D-木酮糖-5-磷酸还原酶 IDS-异戊烯基焦磷酸异构酶 FPS-法呢基焦磷酸合酶 DBR2-双键还原酶2 CPR-细胞色素P450还原酶

3.2 调控青蒿素生物合成相关的激素信号传导

外源JA/MeJA、SA、ABA和GA等多种激素促进青蒿素生物合成离不开转录因子的参与,如ABA可激活AabZIP1转录因子上调和表达[37]。JA能激活多种转录因子,促进GSTs发育及激活青蒿素生物合成基因转录[13,77]。目前,转录因子参与激素信号传导调控青蒿素生物合成的研究已获得较大进展,部分重要调控机制逐步得到揭示。

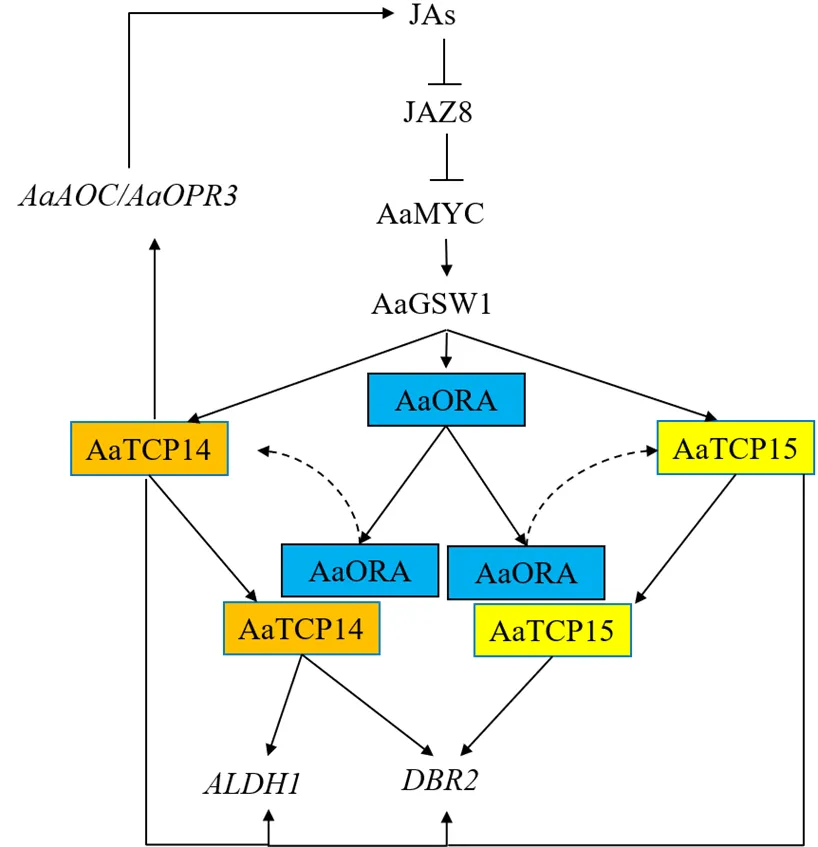

3.2.1 调控JAs信号传导 JAs是研究最多也是促进青蒿素生物合成最有效的植物激素,能上调青蒿素合成酶基因、、和转录因子表达、促进GSTs形成与发育,提高青蒿素及其衍生物含量[47,77]。JA信号介导的转录调控核心模型是SCFCOI1-JAZs-MYC2复合体,在JA作用下,转录抑制因子JAZ蛋白降解,释放出MYC2等转录因子激活下游JAs应答基因表达。研究表明,转录因子参与JA调控青蒿素生物合成的作用包括2个方面,一是激活JA生物合成关键基因,如AaTCP14上调丙二烯氧化环化酶基因(allene oxide cyclase,)和12-羰-植物二烯酸还原酶3基因(12-oxo-phytodienoic acid reductase 3,)表达,促进内源性JA生物合成,进而提高青蒿素产量[47]。二是激活JAs应答因子,促进JA信号传导,上调青蒿素生物合成基因表达。早期发现,在MeJA作用下,AP2/ERF转录因子(AaTAR1、AaERF1、AaERF2)、AaWRKY1、AabHLH1表达增加,分别与、启动子GCC-box/RAA/CBF2、W-box、E-box结合,上调基因表达[28,34-35,43]。随着AaORA[36]、AaGSW1[32]、AaMYC2[45]、AaTCP14[47]、AaTCP15[48]等转录因子功能的相继确定,JA促进青蒿素生物合成的转录调控网络逐渐被揭示。bHLH转录因子AaMYC2受AaJAZs负调控,既是响应JA信号通路的核心调节因子,也是GA信号抑制子AaDELLAs调控节点[78],过表达AaMYC2或AaMYC2-like,可激活、启动子G-box基序,提高基因表达水平,显著提高青蒿素生物合成能力[45-46]。黄花蒿转录因子除单独调控青蒿素生物合成基因表达外,还与其他转录因子形成复合体,以级联方式提高转录调控效率。如GST特异性WRKY转录因子AaGSW1除直接上调表达外,AaMYC2、AabZIP1(响应ABA信号)可分别与AaGSW1启动子G-box、ABRE基序结合,并通过AaORA间接上调、表达,从而在JA信号传导上游形成AaMYC2-AaGSW1-AaORA转录级联调控模式[32]。AaORA是另一个在GST特异性表达的AP2/ERF转录因子,上调、、及转录因子基因表达[36]。基于AaORA与长春花(L.) G. Don中调控萜类吲哚生物碱生物合成的关键转录因子CrORCAs[79]、烟草L.中调控尼古丁生物合成的NIC2-基因座关键转录因子ERFs高度同源[80]及JA信号下游转录因子CrORCA2/CrORCA3受CrMYC2调控[81]等研究结果,推测AaORA是JA信号传导的重要调控因子,在青蒿素生物合成调控中起关键作用(或核心作用)。在JA信号传导下游,AaORA转录因子对青蒿素生物合成基因的调控既部分依赖于AaTCP14(AaTCP14与AaORA的C端结合,形成AaTCP14-AaORA转录激活复合体,协同增强、转录活性,该复合体的形成受AaJAZ8负调控,且AaJAZ8减弱AaTCP14-AaORA对的激活作用),又能独立行使调控作用(AaTCP14只能调控、转录活性,AaORA还能调控转录活性)[47]。与AaTCP14相似,其同源转录因子AaTCP15也能与AaORA的C端、N端结合,形成AaTCP15-AaORA复合体协同调控活性(与AaTCP14-AaORA不同的是AaTCP15-AaORA不能激活基因转录)或直接激活、转录,推动代谢流从青蒿醛向二氢青蒿醛方向转化,提高青蒿素含量[48]。AaMYC2-AaGSW1-AaORA/ AaTCP14(AaTCP15)转录级联调控模式的阐明为JAs调控青蒿素生物合成的动态调控机制研究提供了更好的研究平台(图4)。

图4 JA信号调控青蒿素生物合成的AaMYC2-AaGSW1-AaORA/AaTCP14 (AaTCP15) 转录级联模式

3.2.2 调控ABA信号传导 ABA除调节干旱、寒冷和渗透胁迫等应激反应外,也是植物次生代谢的关键调节因子。在青蒿素生物合成中,外源ABA激活合成酶基因表达,提高青蒿素含量[82-83]。目前已发现多种转录因子参与ABA信号通路调控,其中bZIP家族A组能与ABA响应元件(ABA-responsive elements,ABRE)结合,该组中ABF1、ABF2、ABF3、ABI5等是调控ABA信号的重要转录因子,被称为ABI5-ABF-AREB亚家族。研究发现黄花蒿中有145个bZIP转录因子,其中64个在GSTs表达,ABI5-ABF-AREB亚家族的AaABF3能激活启动子G-box,上调基因表达[39]。AabZIP1的N末端C1结构域含有保守的丝氨酸和苏氨酸残基,是响应ABA信号的关键,该结构域变异后AabZIP1无法响应ABA信号[37]。当黄花蒿体内ABA增加时,ABA先与AaPYL9受体结合启动ABA信号传导,随后该复合体与2C型蛋白磷酸酶AaPP2C1结合(AaPYL9的P89S、H116A被替换以及AaPP2C1第3磷酸化位点基序的G199D被替换或缺失,则两者相互作用即消除),从而释放在静息状态下被AaPP2C1抑制的SnRK2类激酶AaAPK1[84-86]。随着AaAPK1的激活,下游AabZIP1的Ser37位点被AaAPK1磷酸化,继而激活AaGSW1、AaORA、AaTCP14/AaTCP15等转录因子活性,以AabZIP1-AaGSW1-AaTCP14(AaTCP15)/AaORA级联方式或直接与、启动子ABRE基序结合,上调青蒿素合成酶基因表达,提高青蒿素及其衍生物含量[32,47-48,86]。

3.2.3 调控GAs信号传导 GAs是一种二萜类植物激素,参与种子萌发、植物开花、环境胁迫等过程。在植物体内,GAs与青蒿素共用萜类生物合成上游途径,FPP是两者生物合成分支点。目前,GAs中活性最强的GA3对青蒿素的调控作用仍存在一定争议,有研究认为外源GA3可能通过刺激SA合成,触发活性氧生成,从而促进青蒿素生物合成基因表达和/或提高青蒿素合成代谢流以增加青蒿素积累[87-89],也有研究认为GA3并未显著促进青蒿素生物合成或增加GSTs数量(密度),仅促进GSTs个体增大[56]。Chen等[90]研究也指出,真正有效促进青蒿素生物合成的是GA4和GA1,而不是GA3。另外,过表达GA4/GA1前体GA20/GA9生物合成关键酶基因,促进转基因植物枝条数量增加,株高增长,GSTs个体增大、密度提高,青蒿素含量增长2倍[91],该研究进一步表明GA4/GA1可能是青蒿素生物合成的主要活性GAs。在GAs信号通路中,转录因子同样发挥重要作用,当植物感受到GA(GA4/GA1)信号时,R2R3-MYB、HD-ZIP IV、C2H2锌指蛋白和bHLH转录因子家族随即参与GA信号调节,AaMYB1促进和表达,提高GA9向GA4的转化效率[17],尤其是MYB转录因子AaMIXTA1表达显著上调,并通过AaHD8正调控GSTs形成[27,90],或与、、和启动子的GA响应元件GARE基序结合,上调青蒿素生物合成基因表达[17]。

3.2.4 调控SA信号传导 SA是一种调节植物生长发育、光合作用、蒸腾作用以及诱导致病基因表达、促进次生代谢产物合成的重要酚类激素。施用外源SA,可激活、等青蒿素生物合成前期基因转录表达,刺激细胞产生活性氧,促进二氢青蒿酸转化为青蒿素,而对生物合成后期基因的表达影响不大[92-93]。在SA信号通路中,病程相关基因非表达子(non-expressor of pathogenesis-related genes,NPR)基因家族及bZIP类转录因子TGA起着关键作用。NPR包含ANK和BTB/POZ 2个结构域,通过ANK结构域介导,NPR的BTB/POZ结构域与TGA转录因子结合,发挥调控作用[94]。黄花蒿中检测到6个TGA转录因子和5个基因,其中AaNPR1作为转录共激活因子与AaTGA6相互作用,增强AaTGA6与启动子TGACG基序的结合能力,进而增加下游基因表达,而AaTGA3则与AaTGA6相互作用形成异二聚体,负调控AaTGA6与的结合。AaTGA6是青蒿素生物合成的重要调控因子,在过表达植株中,mRNA水平增加11~15倍,mRNA水平增加2~3倍,、、基因表达水平提高1~7倍,青蒿素含量提高90%~120%[40]。

上述研究表明,转录因子调控激素信号的传导是一个相当复杂的过程,加之部分转录因子,如AaGSW1[32]、AabHLH1[43,95]、AaTCP15[48]等同时参与调控2种及2种以上激素信号应答,相互形成多种交叉调控,大大增加了转录因子调控网络的研究难度。

3.3 调控青蒿素生物合成相关的光信号传导

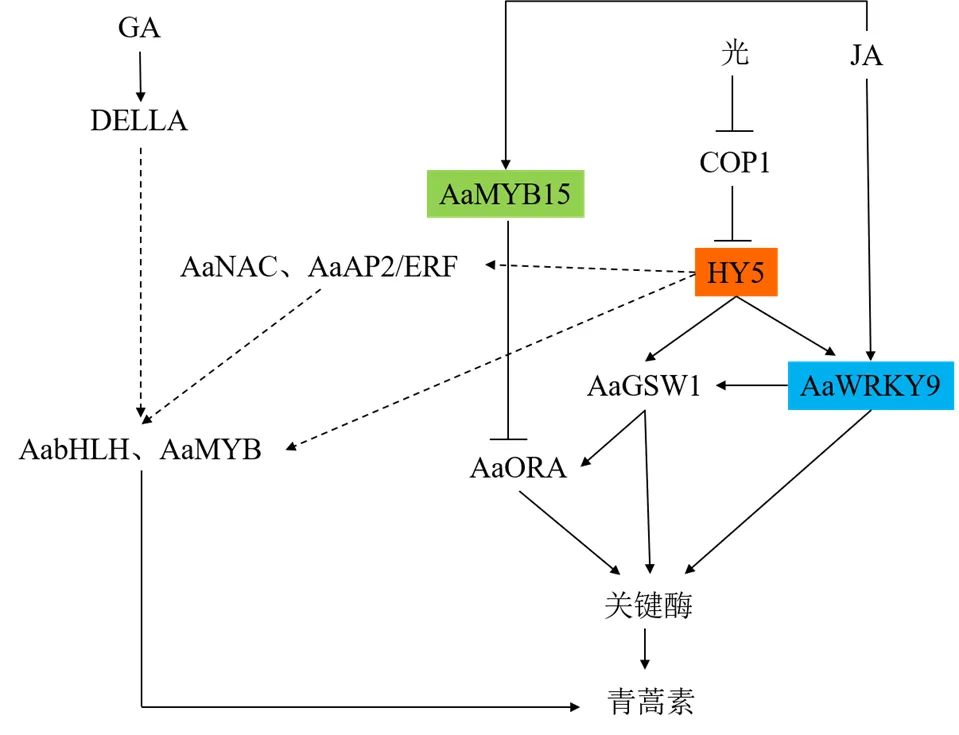

光是调节青蒿素生物合成的另一重要因子。研究显示,过表达蓝光受体AtCRY1促进和转录,过表达光敏色素互作因子PIF3上调、、基因表达,红光、蓝光显著提高青蒿素及其衍生物含量,冷白光促进黄花蒿毛状根形成及青蒿素生物合成,UVB辐照激活、、、和基因表达[96],而暗处理使、、基因的mRNA水平下调10倍以上[13]。植物具有极其精细的光接收(如感受红光和远红光的光敏色素、感受蓝光/UVA的隐花色素和趋光色素、感受UVB的紫外光受体UVR8)和信号传系统将光传递到光调控因子(如bZIP转录因子HY5、光形态建成调控因子COP1)调控相关基因表达。AaHY5有3个结构域,分别是与DNA结合的bZIP结构域、COP1位点及酪蛋白激酶II磷酸化位点。AaHY5和AaCOP1是作用相反的2个因子,在黑暗条件下,细胞核内AaCOP1聚集,负调控AaHY5生成;在光照条件下,细胞核内AaCOP1降低,AaHY5的积累启动光形态建成,并激活表达,直接或进而激活AaORA间接正调控青蒿素生物合成(图5)[41]。此外、、、、、等转录因子基因在响应光信号时表达上调,表达下调,这些转录因子可能也参与光信号调控[15,19]。

图5 光与GA/JA对青蒿素生物合成的协同调控模式

JA、GA等激素调控青蒿素生物合成需要光的介导,两者具有协同增效作用,当激素和光组合处理时,青蒿素生物合成关键基因、、、的表达水平显著高于光或激素单独处理[13,16]。研究表明,激素和光对青蒿素生物合成的协同增效作用与转录因子的调控作用密不可分,现已发现多种转录因子参与介导光与激素的协同增效过程,涉及bHLH、MYB、NAC、WRKY、ERF、LSD、HD-ZIP和E2F/DP等多个转录因子家族,推测的调控机制如图5所示[13,16]。其中AaWRKY9、AaMYB15 2个转录因子的研究较为深入,AaWRKY9是一个由光或JA双重诱导的腺毛特异性转录因子,的表达受AaHY5正调控,AaJAZ9负调控。在光下,AaHY5积累增加,AaHY5与启动子的G-box结合后上调表达;缺乏JA时,AaJAZ9抑制表达。因此,在仅有光或JA时,促进下游基因表达的能力有限,只有在光和JA同时存在时,表达增加且AaJAZ9被降解,大量的AaWRKY9与启动子W-box基序结合,协同提升青蒿素生物合成能力[29]。而AaMYB15是一个负调控因子,暗处理和JA处理可诱导表达,光照抑制其表达。AaMYB15能直接下调、、、等基因表达,或与启动子结合并抑制其活性,间接下调青蒿素合成途径关键酶基因表达(图5)[21]。

在自然界,光作为一种不可或缺的环境因素与其他环境因素协同(或拮抗)调节植物次生代谢物的生物合成,其含量和产量与光质、光强、光周期密切相关[96]。尽管已对光质与青蒿素生物合成的调控关系有所了解,并对部分光响应转录因子进行了表征,但光强和光周期的调节机制尚少有涉及,完整的光信号通路仍不清楚,很有必要系统开展光对黄花蒿生长与发育及对青蒿素含量和产量的调控机制研究。

3.4 调控青蒿素生物合成相关的逆境胁迫因子信号传导

除植物激素和光外,一些逆境因子,如盐胁迫、浸水胁迫、低温胁迫、干旱胁迫等也对青蒿素的生物合成产生显著影响,一定程度的盐胁迫、浸水胁迫、低温胁迫能促进青蒿素及其衍生物的积累,而干旱胁迫则减少积累[97]。逆境胁迫对青蒿素生物合成的调节作用与其促进相关酶基因表达及特定转录因子的参与有关,ABF1、APX、CCC1、CPK6、JAZ1、MYC2和JAZ5是潜在的响应因子[98]。研究表明,盐胁迫促进和基因表达[99],24 h浸水处理后和基因表达上调[100],低温促进青蒿素生物合成基因(、、、和)转录水平显著提高、产生高浓度ROS促进青蒿素合成前体转化、抑制竞争途径β-石竹烯合酶基因表达,并通过诱导JA合成及提高JA信号相关转录因子AaERF1、AaERF2、AaORA的调控能力进一步上调青蒿素生物合成基因表达[101-102]。最近发现,AabHLH112是调控冷胁迫信号的重要转录因子,能通过转录因子AaERF1间接上调青蒿素生物合成基因表达[44]。而干旱胁迫下,、、、、等生物合成基因和转录因子基因表达下调[103],过表达干旱胁迫相关转录因子,、、基因表达水平上调,青蒿素含量增加[52]。另据转录组分析也表明,转录因子在盐、浸水、低温、干旱等胁迫应激信号传导中起着不可或缺的作用,有29个转录因子家族参与其中一种或多种胁迫,尤其是NAC和MYB/MYB相关家族的转录因子在上述4种胁迫中均发挥重要作用,是研究转录因子调控逆境胁迫信号传导需要重点关注的家族[97]。

总体来说,目前对转录因子响应黄花蒿逆境胁迫的作用机制研究还不够深入,而且青蒿素含量与胁迫程度、光照强度、黄花蒿生长状态、收获时间等多种因素有关,即使胁迫类型相同,因胁迫程度等因素差异也往往得出不一致的研究结果,如Lv等[52]、Marchese等[104]认为短期缺水有利于青蒿素积累,,基因表达提高3~7倍,而Vashisth等[97]、Yadav等[103]认为长期缺水抑制青蒿素的生物合成。

4 结语与展望

青蒿素作为治疗疟疾的特效药,过去5年间需求量增长25%。近年来,化学合成、代谢工程、合成生物学、高产品种选育等研究为提高青蒿素产量提供了多种方案,但仍有不少难题尚未解决[105]。如化学合成的纯青蒿素产品在药效及耐药性方面不及植物来源的青蒿素[106-107],半合成方法生产青蒿素的成本较高、效率较低,影响了工业化进程[108],代谢工程或选育的新品种优良性状还不能稳定遗传[3,11]。因此,迄今仍未建立一种高效、快速、经济和大量生产青蒿素的有效方法,从植物提取依然是青蒿素生产的主要来源,高含量青蒿素品种的研发仍是解决当前困境的关键。

转录因子作为青蒿素生物合成的高效调控因子,具有调控等基因表达、腺毛形成与发育和激素等信号传导的作用,在提高青蒿素含量或产量方面拥有巨大的潜力,然而利用转录因子提高青蒿素含量或产量的研究还未达到可商业化的目标。基于青蒿素生物合成相关转录因子主要在GSTs中表达,并与等基因表达模式高度一致,目前已利用激光捕获显微切割(laser capture microdissection,LCM)、RNA-seq及染色质免疫共沉淀(chromatin immunoprecipitation,ChIP)技术对近40个转录因子进行克隆、表达及基本功能研究。最近,单细胞测序技术应用于构建基因网络以鉴定在植物发育分化过程中起着关键作用的核心转录因子,以及解析转录因子对植物组织成分、细胞特性及分化的影响等方面显示出广阔的发展前景[109-110],相信随着该技术的应用及相关数据的增多,将大大加快候选转录因子的筛选和功能表征速度,有效提高转录因子的研究精度,增加对青蒿素生物合成转录因子调控网络的认识。同时,先前青蒿素生物合成相关转录因子的研究大多注重靶基因结合位点分析,较少涉及表观遗传学研究,而Pandey等[111]研究表明UVB介导了基因启动子中包括WRKY在内的7个转录因子结合位点的去甲基化,甲基化程度的降低显著促进了基因上调表达和青蒿素合成。因此,注重转录因子/结构基因甲基化/去甲基化等表观遗传研究,可能开启转录因子调控青蒿素生物合成途径研究的新领域。此外,植物基因组中常有一些特定的具有相似表达模式的基因簇参与次生代谢调控,而黄花蒿基因组高度复杂,是典型的大基因组(1.74 Gb)、高杂合度(1.0%~1.5%)、高重复序列(61.57%)、低GC含量(仅31.5%)基因组,其中萜类合酶基因家族显著扩张,是目前已测序植物物种中萜类合酶基因最多的物种之一[12]。从复杂的基因组中鉴定关键转录因子,特别是基因簇调控转录因子及其功能,将为寻找更有效的青蒿素生物合成相关转录因子提供更多机会。总之,通过多种方法构建青蒿素生物合成调控网络,将丰富青蒿素代谢调控理论,助力青蒿素含量或产量进一步提高。

利益冲突 所有作者均声明不存在利益冲突

[1] Ekiert H, Świątkowska J, Klin P,.importance in traditional medicine and current state of knowledge on the chemistry, biological activity and possible applications [J]., 2021, 87(8): 584-599.

[2] Liu C X. Discovery and development of artemisinin and related compounds [J]., 2017, 9(2): 101-114.

[3] 张小波, 郭兰萍, 黄璐琦. 我国黄花蒿中青蒿素含量的气候适宜性等级划分 [J]. 药学学报, 2011, 46(4): 472-478.

[4] Cockram J, Hill C, Burns C,. Screening a diverse collection ofgermplasm accessions for the antimalarial compound, artemisinin [J]., 2012, 10(2): 152-154.

[5] Paddon C J, Westfall P J, Pitera D J,. High-level semi-synthetic production of the potent antimalarial artemisinin [J]., 2013, 496(7446): 528-532.

[6] Zhang L, Jing F Y, Li F P,. Development of transgenic(Chinese wormwood) plants with an enhanced content of artemisinin, an effective anti-malarial drug, by hairpin-RNA-mediated gene silencing [J]., 2009, 52(Pt 3): 199-207.

[7] Chen Y F, Shen Q, Wang Y Y,. The stacked over-expression of FPS, CYP71AV1 and CPR genes leads to the increase of artemisinin level inL. [J]., 2013, 7(3): 287-295.

[8] Shen Q, Yan T X, Fu X Q,. Transcriptional regulation of artemisinin biosynthesis inL. [J]., 2016, 61(1): 18-25.

[9] Malhotra K, Subramaniyan M, Rawat K,. Compartmentalized metabolic engineering for artemisinin biosynthesis and effective malaria treatment by oral delivery of plant cells [J]., 2016, 9(11): 1464-1477.

[10] Judd R, Bagley M C, Li M Z,. Artemisinin biosynthesis in non-glandular trichome cells of[J]., 2019, 12(5): 704-714.

[11] Xie D Y, Ma D M, Judd R,. Artemisinin biosynthesis inand metabolic engineering: Questions, challenges, and perspectives [J]., 2016, 15(6): 1093-1114.

[12] Shen Q, Zhang L D, Liao Z H,. The genome ofprovides insight into the evolution of Asteraceae family and artemisinin biosynthesis [J]., 2018, 11(6): 776-788.

[13] Hao X L, Zhong Y J, Fu X Q,. Transcriptome analysis of genes associated with the artemisinin biosynthesis by jasmonic acid treatment under the light in[J]., 2017, 8: 971.

[14] Olofsson L, Lundgren A, Brodelius P E. Trichome isolation with and without fixation using laser microdissection and pressure catapulting followed by RNA amplification: Expression of genes of terpene metabolism in apical and sub-apical trichome cells ofL [J]., 2012, 183: 9-13.

[15] Pan W S, Zheng L P, Tian H,. Transcriptome responses involved in artemisinin production inL. under UV-B radiation [J]., 2014, 140: 292-300.

[16] Ma T Y, Gao H, Zhang D,. Transcriptome analyses revealed the ultraviolet B irradiation and phytohormone gibberellins coordinately promoted the accumulation of artemisinin inL. [J]., 2020, 15: 67.

[17] Matías-Hernández L, Jiang W M, Yang K,. AaMYB1 and its orthologue AtMYB61 affect terpene metabolism and trichome development inand[J]., 2017, 90(3): 520-534.

[18] 苏航. 青蒿MYB类转录因子MYB2调控腺毛发育的功能研究 [D]. 泉州: 华侨大学, 2018.

[19] Li Y P, Qin W, Fu X Q,. Transcriptomic analysis reveals the parallel transcriptional regulation of UV-B-induced artemisinin and flavonoid accumulation inL. [J]., 2021, 163: 189-200.

[20] Xie L H, Yan T X, Li L,. An HD-ZIP-MYB complex regulates glandular secretory trichome initiation in[J]., 2021, 231(5): 2050-2064.

[21] Wu Z, Li L, Liu H,. AaMYB15, an R2R3-MYB TF in, acts as a negative regulator of artemisinin biosynthesis [J]., 2021, 308: 110920.

[22] Qin W, Xie L H, Li Y P,. An R2R3-MYB transcription factor positively regulates the glandular secretory trichome initiation inL. [J]., 2021, 12: 657156.

[23] Shi P, Fu X Q, Shen Q,. The roles of AaMIXTA1 in regulating the initiation of glandular trichomes and cuticle biosynthesis in[J]., 2018, 217(1): 261-276.

[24] Lv Z Y, Li J X, Qiu S,. The transcription factors TLR1 and TLR2 negatively regulate trichome density and artemisinin levels in[J]., 2022, 64(6): 1212-1228.

[25] Zhou Z, Tan H X, Li Q,. Trichome and artemisinin regulator 2 positively regulates trichome development and artemisinin biosynthesis in[J]., 2020, 228(3): 932-945.

[26] Yan T X, Chen M H, Shen Q,. HOMEODOMAIN PROTEIN 1 is required for jasmonate-mediated glandular trichome initiation in[J]., 2017, 213(3): 1145-1155.

[27] Yan T X, Li L, Xie L H,. A novel HD-ZIP IV/MIXTA complex promotes glandular trichome initiation and cuticle development in[J]., 2018, 218(2): 567-578.

[28] Ma D M, Pu G B, Lei C Y,. Isolation and characterization of AaWRKY1, antranscription factor that regulates the amorpha-4,11-diene synthase gene, a key gene of artemisinin biosynthesis [J]., 2009, 50(12): 2146-2161.

[29] Fu X Q, Peng B W, Hassani D,. AaWRKY9 contributes to light- and jasmonate-mediated to regulate the biosynthesis of artemisinin in[J]., 2021, 231(5): 1858-1874.

[30] Chen T T, Li Y P, Xie L H,. AaWRKY17, a positive regulator of artemisinin biosynthesis, is involved in resistance toin[J]., 2021, 8(1): 217.

[31] de Paolis A, Caretto S, Quarta A,. Genome-wide identification of WRKY genes in: Characterization of a putative ortholog of[J]., 2020, 9(12): E1669.

[32] Chen M H, Yan T X, Shen Q,. GLANDULAR TRICHOME-SPECIFIC WRKY1 promotes artemisinin biosynthesis in[J]., 2017, 214(1): 304-316.

[33] Xie L H, Yan T X, Li L,. The WRKY transcription factor AaGSW2 promotes glandular trichome initiation in[J]., 2021, 72(5): 1691-1701.

[34] Tan H X, Xiao L, Gao S H,. Trichome and artemisinin regulator 1 is required for trichome development and artemisinin biosynthesis in[J]., 2015, 8(9): 1396-1411.

[35] Yu Z X, Li J X, Yang C Q,. The jasmonate-responsive AP2/ERF transcription factors AaERF1 and AaERF2 positively regulate artemisinin biosynthesis inL [J]., 2012, 5(2): 353-365.

[36] Lu X, Zhang L, Zhang F Y,. AaORA, a trichome-specific AP2/ERF transcription factor of, is a positive regulator in the artemisinin biosynthetic pathway and in disease resistance to[J]., 2013, 198(4): 1191-1202.

[37] Zhang F Y, Fu X Q, Lv Z Y,. A basic leucine zipper transcription factor, AabZIP1, connects abscisic acid signaling with artemisinin biosynthesis in[J]., 2015, 8(1): 163-175.

[38] Shen Q, Huang H Y, Zhao Y,. The transcription factor Aabzip9 positively regulates the biosynthesis of artemisinin in[J]., 2019, 10: 1294.

[39] Zhong Y J, Li L, Hao X L,. AaABF3, an abscisic acid-responsive transcription factor, positively regulates artemisinin biosynthesis in[J]., 2018, 9: 1777.

[40] Lv Z Y, Guo Z Y, Zhang L D,. Interaction of bZIP transcription factor TGA6 with salicylic acid signaling modulates artemisinin biosynthesis in[J]., 2019, 70(15): 3969-3979.

[41] Hao X L, Zhong Y J, Nï Tzmann H W,. Light-induced artemisinin biosynthesis is regulated by the bZIP transcription factor AaHY5 in[J]., 2019, 60(8): 1747-1760.

[42] Zhang Q Z, Wu N Y, Jian D Q,. Overexpression of AaPIF3 promotes artemisinin production in[J]., 2019, 138: 111476.

[43] Li L, Hao X L, Liu H,. Jasmonic acid-responsive AabHLH1 positively regulates artemisinin biosynthesis in[J]., 2019, 66(3): 369-375.

[44] Xiang L E, Jian D Q, Zhang F Y,. The cold-induced transcription factor bHLH112 promotes artemisinin biosynthesis indirectly via ERF1 in[J]., 2019, 70(18): 4835-4848.

[45] Shen Q, Lu X, Yan T X,. The jasmonate-responsive AaMYC2 transcription factor positively regulates artemisinin biosynthesis in[J]., 2016, 210(4): 1269-1281.

[46] Majid I, Kumar A, Abbas N. A basic helix loop helix transcription factor, AaMYC2-Like positively regulates artemisinin biosynthesis inL [J]., 2019, 128: 115-125.

[47] Ma Y N, Xu D B, Li L,. Jasmonate promotes artemisinin biosynthesis by activating the TCP14-ORA complex in[J]., 2018, 4(11): eaas9357.

[48] Ma Y N, Xu D B, Yan X,. Jasmonate- and abscisic acid-activated AaGSW1-AaTCP15/AaORA transcriptional cascade promotes artemisinin biosynthesis in[J]., 2021, 19(7): 1412-1428.

[49] Lv Z Y, Wang Y, Liu Y,. The SPB-box transcription factor AaSPL2 positively regulates artemisinin biosynthesis inL [J]., 2019, 10: 409.

[50] Kayani S I, Shen Q, Ma Y N,. The YABBY family transcription factor AaYABBY5 directly targets cytochrome P450 monooxygenase (CYP71AV1) and double-bond reductase 2 (DBR2) involved in artemisinin biosynthesis in[J]., 2019, 10: 1084.

[51] Tang Y L, Li L, Yan T X,. AaEIN3 mediates the downregulation of artemisinin biosynthesis by ethylene signaling through promoting leaf senescence in[J]., 2018, 9: 413.

[52] Lv Z Y, Wang S, Zhang F Y,. Overexpression of a noveldomain-containing transcription factor gene (AaNAC1) enhances the content of artemisinin and increases tolerance to drought andin[J]., 2016, 57(9): 1961-1971.

[53] Soetaert S S, van Neste C M, Vandewoestyne M L,. Differential transcriptome analysis of glandular and filamentous trichomes in[J]., 2013, 13: 220.

[54] Pulice G, Pelaz S, Matías-Hernández L. Molecular farming in, a promising approach to improve anti-malarial drug production [J]., 2016, 7: 329.

[55] Wang Y T, Fu X Q, Xie L H,. Stress associated protein 1 regulates the development of glandular trichomes in[J]., 2019, 139(2): 249-259.

[56] Liu S Q, Tian N, Li J,. Isolation and identification of novel genes involved in artemisinin production from flowers ofusing suppression subtractive hybridization and metabolite analysis [J]., 2009, 75(14): 1542-1547.

[57] Ram M, Khan M A, Jha P,. HMG-CoA reductase limits artemisinin biosynthesis and accumulation inL. plants [J]., 2010, 32(5): 859-866.

[58] Olsson M E, Olofsson L M, Lindahl A L,. Localization of enzymes of artemisinin biosynthesis to the apical cells of glandular secretory trichomes ofL [J]., 2009, 70(9): 1123-1128.

[59] Schramek N, Wang H H, Römisch-Margl W,. Artemisinin biosynthesis in growing plants of. A13CO2study [J]., 2010, 71(2/3): 179-187.

[60] Wang H Z, Han J L, Kanagarajan S,. Trichome-specific expression of the-4, 11-diene 12-hydroxylase (cyp71av1) gene, encoding a key enzyme of artemisinin biosynthesis in, as reported by a promoter-fusion [J]., 2013, 81(1/2): 119-138.

[61] Wang Y Y, Yang K, Jing F Y,. Cloning and characterization of trichome-specific promoter of cpr71av1 gene involved in artemisinin biosynthesis inL [J]., 2011, 45(5): 817-824.

[62] Teoh K H, Polichuk D R, Reed D W,.L. (Asteraceae) trichome-specific cDNAs reveal CYP71AV1, a cytochrome P450 with a key role in the biosynthesis of the antimalarial sesquiterpene lactone artemisinin [J]., 2006, 580(5): 1411-1416.

[63] Wu T, Wang Y J, Guo D J. Investigation of glandular trichome proteins inL. using comparative proteomics [J]., 2012, 7(8): e41822.

[64] Teoh K H, Polichuk D R, Reed D W, et al. Molecular cloning of an aldehyde dehydrogenase implicated in artemisinin biosynthesis in[J]., 2009, 87(6): 635-642.

[65] Brown G D, Sy L K.transformations of artemisinic acid inplants [J]., 2007, 63(38): 9548-9566.

[66] Rydén A M, Ruyter-Spira C, Quax W J,. The molecular cloning of dihydroartemisinic aldehyde reductase and its implication in artemisinin biosynthesis in[J]., 2010, 76(15): 1778-1783.

[67] Suberu J, Gromski P S, Nordon A,. Multivariate data analysis and metabolic profiling of artemisinin and related compounds in high yielding varieties offield-grown in Madagascar [J]., 2016, 117: 522-531.

[68] Alejos-Gonzalez F, Qu G S, Zhou L L,. Characterization of development and artemisinin biosynthesis in self-pollinatedplants [J]., 2011, 234(4): 685-697.

[69] Czechowski T, Larson T R, Catania T M,.mutant impaired in artemisinin synthesis demonstrates importance of nonenzymatic conversion in terpenoid metabolism [J]., 2016, 113(52): 15150-15155.

[70] Bryant L, Flatley B, Patole C,. Proteomic analysis of: Towards elucidating the biosynthetic pathways of the antimalarial pro-drug artemisinin [J]., 2015, 15: 175.

[71] Zhang Y S, Liu B Y, Li Z Q,. Molecular cloning of a classical plant peroxidase fromand its effect on the biosynthesis of artemisinin[J]., 2004, 46: 1338-1346.

[72] Nair P, Misra A, Singh A,. Differentially expressed genes during contrasting growth stages offor artemisinin content [J]., 2013, 8(4): e60375.

[73] Nair P, Shasany A K, Khan F,. Differentially expressed peroxidases fromand their responses to various abiotic stresses [J]., 2018, 36(2): 295-309.

[74] Nair P, Mall M, Sharma P,. Characterization of a class III peroxidase from: Relevance to artemisinin metabolism and beyond [J]., 2019, 100(4/5): 527-541.

[75] Hassani D, Fu X Q, Shen Q,. Parallel transcriptional regulation of artemisinin and flavonoid biosynthesis [J]., 2020, 25(5): 466-476.

[76] 扎西次仁, 张巧卓, 杨春贤, 等. AaPIF3对青蒿素生物合成基因及AaERF1的转录调控研究 [J]. 西南大学学报: 自然科学版, 2020, 42(10): 65-73.

[77] Maes L, van Nieuwerburgh F C, Zhang Y S,. Dissection of the phytohormonal regulation of trichome formation and biosynthesis of the antimalarial compound artemisinin inplants [J]., 2011, 189(1): 176-189.

[78] Shen Q, Cui J, Fu X Q,. Cloning and characterization of DELLA genes in[J]., 2015, 14(3): 10037-10049.

[79] van der Fits L, Memelink J. ORCA3, a jasmonate-responsive transcriptional regulator of plant primary and secondary metabolism [J]., 2000, 289(5477): 295-297.

[80] Shoji T, Kajikawa M, Hashimoto T. Clustered transcription factor genes regulate nicotine biosynthesis in tobacco [J]., 2010, 22(10): 3390-3409.

[81] Zhang H T, Hedhili S, Montiel G,. The basic helix-loop-helix transcription factor CrMYC2 controls the jasmonate-responsive expression of the ORCA genes that regulate alkaloid biosynthesis in[J]., 2011, 67(1): 61-71.

[82] Jing F Y, Zhang L, Li M Y,. Abscisic acid (ABA) treatment increases artemisinin content inby enhancing the expression of genes in artemisinin biosynthetic pathway [J]., 2009, 64(2): 319-323.

[83] Zebarjadi A, Dianatkhah S, Pour Mohammadi P,. Influence of abiotic elicitors on improvement production of artemisinin in cell culture ofL. [J].(), 2018, 64(9): 1-5.

[84] Zhang F Y, Lu X, Lv Z Y,. Overexpression of theorthologue of ABA receptor, AaPYL9, enhances ABA sensitivity and improves artemisinin content inL [J]., 2013, 8(2): e56697.

[85] Zhang F Y, Fu X Q, Lv Z Y,. Type 2C phosphatase 1 ofL. is a negative regulator of ABA signaling [J]., 2014, 2014: 521794.

[86] Zhang F Y, Xiang L E, Yu Q,. Artemisinin biosynthesis promoting kinase 1 positively regulates artemisinin biosynthesis through phosphorylating aabzip1 [J]., 2018, 69(5): 1109-1123.

[87] Zhang Y S, Ye H C, Liu B Y,. Exogenous GA3 and flowering induce the conversion of artemisinic acid to artemisinin inplants [J]., 2005, 52(1): 58-62.

[88] Banyai W, Mii M, Supaibulwatana K. Enhancement of artemisinin content and biomass inby exogenous GA3 treatment [J]., 2011, 63(1): 45-54.

[89] Guo X X, Yang X Q, Yang R Y,. Salicylic acid and methyl jasmonate but not Rose Bengal enhance artemisinin production through invoking burst of endogenous singlet oxygen [J]., 2010, 178(4): 390-397.

[90] Chen R B, Bu Y J, Ren J Z,. Discovery and modulation of diterpenoid metabolism improves glandular trichome formation, artemisinin production and stress resilience in[J]., 2021, 230(6): 2387-2403.

[91] Inthima P, Nakano M, Otani M,. Overexpression of the gibberellin 20-oxidase gene fromresulted in modified trichome formation and terpenoid metabolities ofL [J].2017, 129(2): 223-236.

[92] Pu G B, Ma D M, Chen J L,. Salicylic acid activates artemisinin biosynthesis inL. [J]., 2009, 28(7): 1127-1135.

[93] Yin H, Kjaer A, Fretté X C,. Chitosan oligosaccharide and salicylic acid up-regulate gene expression differently in relation to the biosynthesis of artemisinin inL [J]., 2012, 47(11): 1559-1562.

[94] Wang W, Withers J, Li H,. Structural basis of salicylic acid perception byNPR proteins [J]., 2020, 586(7828): 311-316.

[95] Ji Y P, Xiao J W, Shen Y L,. Cloning and characterization of AabHLH1, abHLH transcription factor that positively regulates artemisinin biosynthesis in[J]., 2014, 55(9): 1592-1604.

[96] Zhang S C, Zhang L, Zou H Y,. Effects of light on secondary metabolite biosynthesis in medicinal plants [J]., 2021, 12: 781236.

[97] Vashisth D, Kumar R, Rastogi S,. Transcriptome changes induced by abiotic stresses in[J]., 2018, 8(1): 3423.

[98] Alam P, Balawi T A.identification of-regulatory elements and their functional annotations from assembled ESTs ofL. involved in abiotic stress signaling [J]., 2021, 26(2): 2384-2395.

[99] Yadav R K, Sangwan R S, Srivastava A K,. Prolonged exposure to salt stress affects specialized metabolites-artemisinin and essential oil accumulation inL.: Metabolic acclimation in preferential favour of enhanced terpenoid accumulation accompanying vegetative to reproductive phase transition [J]., 2017, 254(1): 505-522.

[100] Yang R Y, Zeng X M, Lu Y Y,. Senescent leaves ofare one of the most active organs for overexpression of artemisinin biosynthesis responsible genes upon burst of singlet oxygen [J]., 2010, 76(7): 734-742.

[101] 杨瑞仪, 卢元媛, 杨雪芹, 等. 低温诱导黄花蒿中青蒿素的生物合成及其机制研究 [J]. 中草药, 2012, 43(2): 350-354.

[102] Liu W H, Wang H Y, Chen Y P,. Cold stress improves the production of artemisinin depending on the increase in endogenous jasmonate [J]., 2017, 64(3): 305-314.

[103] Yadav R K, Sangwan R S, Sabir F,. Effect of prolonged water stress on specialized secondary metabolites, peltate glandular trichomes, and pathway gene expression inL. [J]., 2014, 74: 70-83.

[104] Marchese J A, Ferreira J F S, Rehder V L G,. Water deficit effect on the accumulation of biomass and artemisinin in annual wormwood (L., Asteraceae) [J]., 2010, 22(1): 1-9.

[105] Wani K I, Choudhary S, Zehra A,. Enhancing artemisinin content in and delivery from: A review of alternative, classical, and transgenic approaches [J]., 2021, 254(2): 29.

[106] Elfawal M A, Towler M J, Reich N G,. Dried whole-plantslows evolution of malaria drug resistance and overcomes resistance to artemisinin [J]., 2015, 112(3): 821-826.

[107] Desrosiers M R, Mittelman A, Weathers P J. Dried leafimproves bioavailability of artemisinin via cytochrome P450 inhibition and enhances artemisinin efficacy downstream [J]., 2020, 10(2): 254.

[108] Turconi J, Griolet F, Guevel R,. Semisynthetic artemisinin, the chemical path to industrial production [J]., 2014, 18(3): 417-422.

[109] Liu Z X, Zhou Y P, Guo J G,. Global dynamic molecular profiling of stomatal lineage cell development by single-cell RNA sequencing [J]., 2020, 13(8): 1178-1193.

[110] Shahan R, Hsu C W, Nolan T M,. A single-cellroot atlas reveals developmental trajectories in wild-type and cell identity mutants [J]., 2022, 57(4): 543-560.

[111] Pandey N, Pandey-Rai S. Deciphering UV-B-induced variation in DNA methylation pattern and its influence on regulation of DBR2 expression inL. [J]., 2015, 242(4): 869-879.

Research progress on transcriptional regulation mechanism of artemisinin biosynthesis

ZHAN Zhong-gen

Biopharmaceutical Laboratory, Zhejiang Institute of Economics and Trade, Hangzhou 310018, China

Artemisinin is an unusual novel endoperoxide sesquiterpene lactone isolated from medicinal plant, has been widely used to treat falciparum malaria. Due to increasing international demand and low content in wildplants, trying to enhance the content or yield of artemisinin become a hotspot. Transcription factors play important roles in regulating a series of genes in the metabolic pathway, and several families of transcription factors have been reported to participate in regulating the biosynthesis and accumulation of artemisinin, and the intervention of transcription factor by genetic engineering is an important method in enhancing the content or yield of artemisinin. Therefore, biosynthesis mechanism of artemisinin from regulating the initiation and development of glandular trichomes and regulating the biosynthesis of artemisinin by transcription factors were reviewed in this paper, in order to provide reference for the transcriptional regulation of artemisinin metabolism.

artemisinin; transcription factor; biosynthesis; trichomes initiation; hormone signal; light signal; adversity stress

R282.1

A

0253 - 2670(2022)19 - 6258 - 15

10.7501/j.issn.0253-2670.2022.19.031

2022-06-09

浙江省自然科学基金资助项目(LGN18C200026);浙江省省属高校基本科研业务费项目(21SBYB08)

詹忠根(1971—),男,教授,硕士,研究方向为药用植物生物技术。E-mail: zhzg9321@163.com

[责任编辑 崔艳丽]

——青蒿素