A Discovery for the Ages

by Zhang Jingwen

“What a large and flat terrace!”Zheng Zhexuan exclaimed, when the archaeologist from the Sichuan Provincial Cultural Relics and Archaeology Research Institute first reached an area in Daocheng County, Garze Tibetan Autonomous Prefecture, southwestern Chinas Sichuan Province.

At the moment, little did he know that the terrace was obscuring extensive Paleolithic ruins, the Piluo site. The well-preserved site showed a clear archaeological sequence through rich cultural relics of unique technical characteristics and multi-cultural elements.

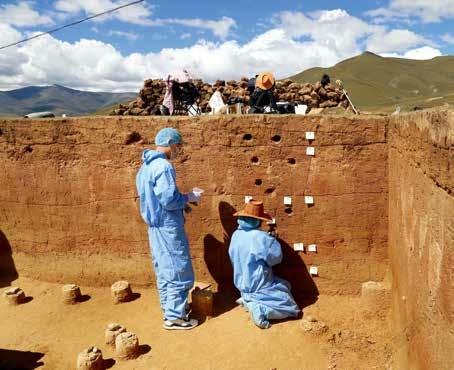

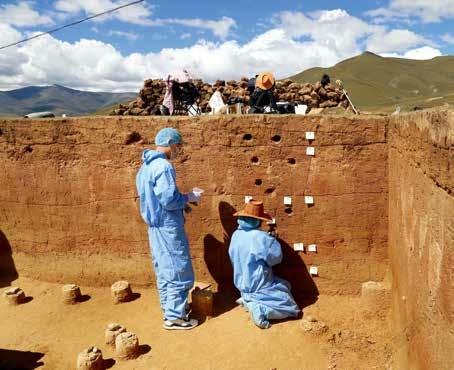

Joy and Hardship of Outdoors Excavation

Production activities of human beings in primitive societies were greatly restricted by natural conditions. The stones used for making tools were mostly quarried from the banks of rivers or nearby rocky areas. Ancient stone tools often provide the greatest insight for the later generations to understand their ancestors during the long history before the emergence of written records.

Zheng Zhexuan is the director of the Paleolithic research department of the Sichuan Provincial Cultural Relics and Archaeology Research Institute. In March 2019, he led a team to conduct archaeological work in Kangding City, capital of Garze Tibetan Autonomous Prefecture. They found a hand axe on a protruding terrace, an iconic stone tool from the Paleolithic period.

“When I first saw the axe, I was a bit hesitant to confirm it,”Zheng admitted. “So I quickly asked a nearby colleague to have a look. He also hesitated for a second, before we shared the joy and confirmation in each others eyes.” Like a ray of sunshine driving the clouds away, the discovery opened the floodgates for the team to conduct a special Paleolithic archaeological investigation.

Zhengs field investigation work plan for April and May 2020 focused on Daocheng County. That is how they came to Piluo and started chipping away the mysteries of the site.

On May 11, 2020, their very first day in Piluo, the team made many discoveries including several stone choppers and blades. The next day, they found the first hand axe, and then the second, third, and more.

So Zheng felt there was something unusual about the site. His suspicions were confirmed by more detailed investigations which uncovered a shocking scene. One field was completely covered with stone wares. “We found at least 20 pieces of hand axes, let alone many others,” he said. That afternoon, a heavy rain accompanied by small hailstones pelted members of the archaeological team. But they were so excited that they preferred to continue digging for stone wares against the rainstorm.

Subsequent daily work of the archaeological team mainly involved excavation, surveying, and mapping of the site. When excavating the Piluo ruins, they cleaned the surface of the Paleolithic site carefully little by little with the simplest tools such as shovels, bamboo sticks, and brushes. During surveying and mapping, they used RTK measuring instruments, electronic theodolites, and photographic equipment to take pictures of all numbered specimens and record 3D coordinates and occurrences as well as performing 3D photographic modeling of the horizontal layers where the relics were densely distributed.

Through the first-stage field excavation, the team estimated that the site could potentially cover about one million square meters. And several more ancient human activity zones were unearthed with over 7,000 specimens.

Delicate Acheulean Hand Axes

The most groundbreaking discovery during the excavation was hand axes highlighting the Acheulean technique. The technique was named after the Saint Acheul archaeological site discovered in Amiens, France.

The Acheulean hand axe was the first standard-made heavy tool in the Paleolithic Age, evidenced by careful trimming on two sides. It represented the highest technical level of stone tool processing and production during the time Homo erectus abounded.

Previously, global archaeologists had been debating whether Acheulean technology existed in East Asia. After participating in a 1944 expedition tour in Southeast Asia, American archaeologist H. L. Movius proposed that hand axes were only found in Paleolithic sites in Western Europe, Africa, West Asia and the South Asian subcontinent, but not in East Asia, Southeast Asia, Siberia, and other places.

Based on this, he drew the so-called “Movius line” that separates those parts of Europe, Africa and Asia with or without Acheulean hand axes. The west of the line was called the “hand-axe cultural circle,” and the east of the line was the “chopping-tool cultural circle.” At the height of ideological confrontation during the Cold War, the “Movius line”was even used to support the fallacy that East Asia was on the fringes of human evolution and development.

With the continuous advancement of archaeological work in China, archaeologists have successively discovered hand axes in Changbai Mountains in northeastern China, Baise City in southern Chinas Guangxi Zhuang Autonomous Region, and other places. But the production level of the stone axes did not meet the classic Acheulean standard.

In recent years, hand axes discovered in the Luonan area in northwestern Chinas Shaanxi Province conformed to the form and technical characteristics of some early Western Acheulean stone tools. But the hand axes were still not thin and symmetrical enough, so some foreign scholars refused to rate them as relics of typical Acheulean technology.

However, the hand axes, thin-blade axes, and other relics found at the Piluo site are not only the remains of Acheulean stone tools discovered at the highest altitude in the world, but also the Acheulean tools with the most typical styles, the most exquisite forms, the most mature technology, and the most complete package in East Asia. They effectively chopped away the half-century-old “Morvis line” debate.

“But we are still unable to determine whether these stone tools were created as a result of continuous technological innovation of the same group of ancestors or as tools brought by the continuous immigration of ethnic groups,” said Zheng Zhexuan. “But we can be sure that the extremely-high-altitude environment of the QinghaiTibet Plateau did not stop the spread of human civilization. The Piluo site provides evidence that early humans could manage the tough living environment on the plateau.”