How China Combats Cultural Racketeering

by Deborah Lehr

China is experiencing a surge in widespread interest in its ancient archaeological heritage. The country opened an average of one new museum every two days between 2016 and 2020. Last March, a livestream of excavations at the Sanxingdui Ruins site in Sichuan Province attracted some four million viewers and over a billion comments and views on Chinas twitter-like social media site Weibo. And it demonstrates that the Chinese market in artifacts, antiques, and fine art is booming. In 2021, it was valued at US$13.4 billion, making up 20 percent of the global total, second only to the United States.

Unfortunately, Chinas antiquities have attracted more than just tourists, viewers, and legitimate buyers—they have also attracted criminal traffickers and looters. But now, the Chinese government is making a serious effort to crack down on such crimes.

For one, China has strengthened its laws, both nationally and locally. By the end of 2016, there were 154 local laws, 138 local government statutes, and more than 13,000 local regulatory documents related to cultural work across the country. China has paired these laws with a much stronger approach to enforcement. In 2021, the country launched a crackdown that caught 650 gangs and resulted in the arrests of 61 of the 62 most-wanted suspects of cultural relic theft. Chinese authorities had recovered more than 150,000 cultural relics from overseas as of September 2021, according to Guangming Daily, a domestic media outlet.

China is also incorporating the protection of cultural history into its broader urbanization planning. This priority is reflected at the very highest levels of the Chinese government. In a message to UNESCO last year, President Xi Jinping emphasized that we “must properly handle the relationship between urban reconstruction and development and the protection and utilization of historical and cultural heritage, and ensure that urban development and heritage protection are well coordinated.”

As part of this coordinated effort, China recently generated a plan on how to use tourism to simultaneously protect culture and generate growth. The National Cultural Heritage Administration of China announced a new web platform that provides information about where to see the stolen objects that have been repatriated back to China. It also features a list of missing international antiquities, and includes two databases: the Stolen(Lost) Cultural Relics Information Publishing Platform of China and the Stolen Foreign Cultural Relics Database which are aimed at retrieving lost cultural property.

Beyond its national efforts, China has taken steps to engage internationally to cooperate in the fight against antiquities trafficking. One notable example is the Cultural Property Agreement(CPA) between China and the United States. This agreement shuts American borders to looted antiquities and stolen art from China, while seeking to increase responsible cultural cooperation and exchange between the two nations. The CPA is a valuable tool against illicit trade, benefiting both countries. By restricting the import of undocumented cultural objects—those which lack a so-called “provenance”or paper trail—into the United States, countries like China can deal an effective blow against the global black market. Beyond the import restrictions themselves, the CPA also provides for mutual cooperation, such as traveling museum exhibitions, professional exchanges, and joint research projects. China has similar bilateral agreements with over 20 other countries around the world on the subject of antiquities protection.

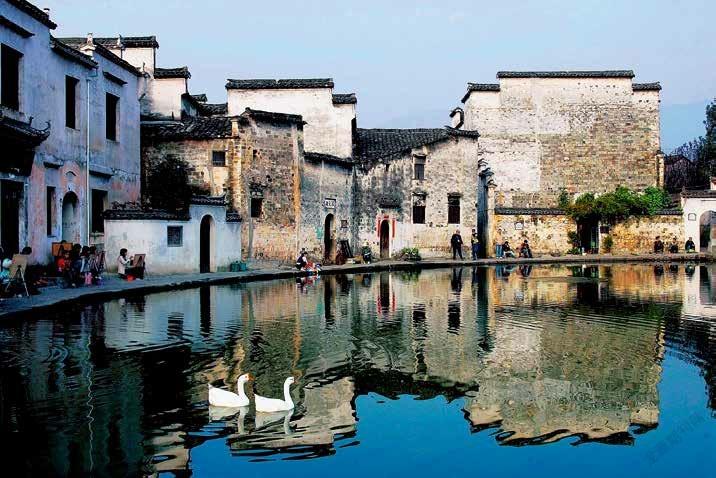

China is also engaging intergovernmental organizations like UNESCO, the cultural arm of the United Nations, as part of its strategy to better protect its heritage. In particular, UNESCOs World Heritage List has become an important platform for China, through which it is securing global recognition for its rich cultural patrimony. In doing so, it is now neck and neck with other top cultural powerhouses, such as Italy, which has 58 designated World Heritage sites. China has 56 sites that have received this status. China is using the international prestige that comes with such a designation as a force multiplier, encouraging local protection of sites as well as domestic tourism, with major economic impacts as a result. For example, only one year after the addition of Xidi and Hongcun, ancient villages in southern Anhui Province, to the World Heritage List, tourism replaced agriculture as the dominant industry in the villages.

In sum, Chinas energetic effort to protect antiquities has made significant progress in recent years. As interest in Chinas artifacts continues to grow, it will be well served by maintaining national efforts to preserve cultural history and by further pursuing global coordination in the fight against illicit antiquities trafficking. The illicit trade in art and antiquities is a global problem that touches every corner of the world. However, Chinas role as a powerhouse in the global art market means that it is uniquely well positioned to take on a more proactive role in fighting the illicit trade of antiquities. As China becomes ground zero for the challenges of antiquities theft, it can also serve as a model for how to fight back and stop their loss.