Recent advances in multidisciplinary therapy for adenocarcinoma of the esophagus and esophagogastric junction

Yi-Han Zheng, En-Hao Zhao

Abstract Esophageal adenocarcinoma (EAC) and adenocarcinoma of the esophagogastric junction (EGJA) have long been associated with poor prognosis. With changes in the spectrum of the disease caused by economic development and demographic changes, the incidence of EAC and EGJA continues to increase, making them worthy of more attention from clinicians. For a long time, surgery has been the mainstay treatment for EAC and EGJA. With advanced techniques, endoscopic therapy, radiotherapy, chemotherapy, and other treatment methods have been developed, providing additional treatment options for patients with EAC and EGJA. In recent decades, the emergence of multidisciplinary therapy (MDT) has enabled the comprehensive treatment of tumors and made the treatment more flexible and diversified, which is conducive to achieving standardized and individualized treatment of EAC and EGJA to obtain a better prognosis. This review discusses recent advances in EAC and EGJA treatment in the surgicalcentered MDT mode in recent years.

Key Words: Multidisciplinary therapy; Esophageal adenocarcinoma; Adenocarcinoma of esophagogastric junction; Endoscopic resection; Surgery

lNTRODUCTlON

Currently, esophageal cancer is ranked 7thin incidence and 6thin overall mortality worldwide, with approximately 70% of cases occurring in males[1]. The most common subtypes of esophageal cancer are esophageal adenocarcinoma (EAC) and esophageal squamous cell carcinoma (ESCC). The two subtypes have very different etiologies; therefore, their incidence varies greatly in different countries and regions.Although its morbidity is much lower than that of ESCC in low-income countries, EAC accounts for two-thirds of esophageal cancer cases in high-income countries. Furthermore, owing to demographic changes, the burden of EAC is expected to increase in the future[2]. Obesity, gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD), and Barrett’s esophagus are some of the main risk factors for EAC. The increasing incidences of obesity and GERD are likely responsible for the continuing increase in the incidence of EAC. Additionally, reduction in chronicHelicobacter pylori(H. pylori) infection has been shown to be negatively correlated with EAC[2].

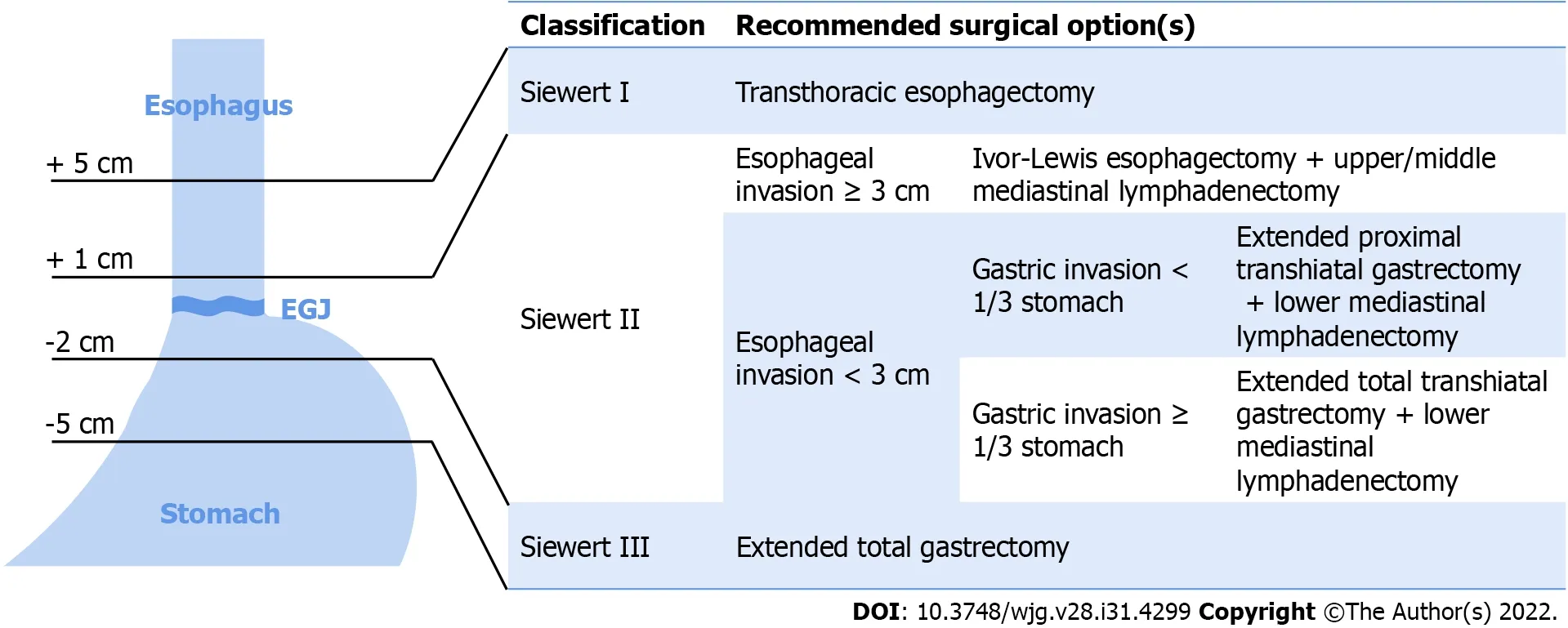

Adenocarcinoma of the esophagogastric junction (EGJA) is a type of cancer that develops at the junction of the esophagus and stomach, and is traditionally known as cardia cancer. According to the standard set by Siewertet al[3] in 1987, esophagogastric carcinoma is defined as a tumor located within 5 cm of the esophagogastric junction (EGJ). Type I was defined when the tumor center was located 1-5 cm above the EGJ, Type II when located from 1 cm above to 2 cm below the EGJ, and Type III when located 2-5 cm below the EGJ. Type II is also known as "real" carcinoma of the cardia. This classification also coincides with the distribution of the cardiac glands[4]. The American Joint Committee on Cancer 8thedition suggests that when the tumor center is located 2 cm below the EGJ or within 2 cm without invasion, it should be staged according to the TNM staging of gastric cancer. When the tumor center is located within 2 cm below the EGJ or with invasion, it should be staged according to the TNM staging of esophageal cancer[5]. Siewert type I EGJA is treated as esophageal cancer, Siewert type III EGJA is classified as gastric cancer, while controversies still exist in the treatment principles for Siewert type II EGJA[6,7]. Evidence indicates that the etiology of EGJA, which is negatively related toH. pyloriinfection and correlates with obesity and GERD injury, is similar to the risk factors for EAC[8].

Currently, surgery remains the primary treatment method for EAC and EGJA. However, due to the anatomical location, gastrointestinal surgeons and thoracic surgeons have different opinions regarding the treatment options. Perioperative therapies, including neoadjuvant and adjuvant therapies, are also gaining attention in the treatment of EAC and EGJA. The importance of multidisciplinary therapy(MDT) in the diagnosis and treatment of tumors has been increasingly emphasized. Clinicians from multiple departments, including radiologists, endoscopists, surgeons, and oncologists, have joined the MDT team to participate in clinical decision making, which has been conducive to the individualization of the diagnosis and treatment of EAC and EGJA.

ENDOSCOPlC RESECTlON: GROWlNG lN lMPORTANCE

For years, surgery has been the only radical treatment for esophageal and EGJ cancer. However, in recent decades, with the development of techniques, endoscopic therapy has gained popularity.Endoscopy has already been used for the early diagnosis of malignant tumors of the esophagus and EGJ, and in suitable patients, endoscopic treatment can be performed. However, endoscopic resection still has limitations and is more commonly used as a diagnostic method than a treatment. A retrospective cohort study demonstrated that, compared to patients who did not undergo continuous endoscopic examination, patients who underwent continuous endoscopy before the diagnosis of EAC were associated with less advanced locoregional staging, better prognosis and survival[9].

Endoscopic radical therapy includes endoscopic tumor resection and ablation of surrounding precancerous tissues to prevent recurrence. The most widely used techniques are endoscopic mucosal resection(EMR) and endoscopic submucosal dissection (ESD). EMR is a relatively safe procedure, with a low risk of postoperative complications. However, it should be noted that during EMR operations, the involved Barrett’s esophagus requires treatment; otherwise, locoregional EMR operations may lead to a high rate of recurrence[10]. Research has shown that the prognosis is relatively acceptable, with approximately 96% of patients achieving complete remission, with a 10-year survival rate of 75%[11]. ESD technology is more demanding than EMR technology. Both EMR and ESD have similar postoperative adverse events, but their incidence is higher following ESD[12]. The most common complications are stenosis,perforation, and bleeding[10]. According to a study, in the postoperative assessment, the recurrence rate after radical resection at 22.9 mo of follow-up was 0.17%[13].

The risk of lymphatic metastasis is relatively low in T1a cancer, but appears to increase with the depth of submucosal infiltration[14]. For EAC, the lymphatic metastasis rate is 0-2% in T1a cancer, and 0-22%, 0-30%, 20%-70% when T1b cancers infiltrate the upper third, the middle third, and the lower third of the submucosa, respectively[15-17]. Therefore, patient selection is essential for endoscopic therapy. EAC endoscopic resection is indicated in T1 carcinomas of differentiation grade G1/G2 without lymphatic invasion, venous invasion, or ulceration. In addition to these criteria, for T1b, infiltration less than 500 μm in depth and less than 20 mm in size is required[14]. Current guidelines usually recommend that additional surgery should be performed after endoscopic resection when the risk of lymphatic metastasis or residual cancer is too high to cure[18]. Meanwhile, if the specimen resected by endoscopic therapy reveals a positive margin on histological examination, additional esophagectomy is also required. Based on some cases of T1 carcinoma that underwent esophageal endoscopic resection with additional esophagectomy, among which 17/30 were cases of EAC, researchers concluded that esophagectomy could achieve further removal of residual advanced cancer or lymphatic metastases in 13% of patients. However, postoperative severe morbidity was 43% and mortality was 7%; therefore, the benefits and risks of close follow-upvssurgery should be considered[19].

In addition, Barrett’s esophagus has been demonstrated to be a significant risk factor for esophageal and EGJ carcinomas. The pathological basis of Barrett’s esophagus is the change in mucosal cells caused by long-term exposure to gastric acid, which can develop into adenocarcinoma. Compared to the normal population, patients with Barrett’s esophagus have a relative risk of 11.3 of developing adenocarcinoma[20]. Due to the relatively high rate of 25% developing into carcinoma, precursor intraepithelial neoplasia in Barrett’s esophagus is usually necessary for endoscopic resection[21].Additionally, removal of low-grade intraepithelial neoplasia is recommended[22].

SURGERY: REMAlNS THE MAlNSTAY OF TREATMENT

Surgical options for esophagus adenocarcinoma

According to the guidelines, the transthoracic approach is usually recommended for the treatment of esophageal carcinoma. For cancers located in the proximal one-third of the esophagus, thoracic esophagectomy can be expanded to three fields, including cervical lymph node dissection. However,controversy remains between transthoracic esophagectomy combined with intrathoracic anastomosis(Ivor-Lewis esophagectomy) and three-field esophagectomy combined with esophagogastrostomy(McKeown esophagectomy); the recommendations of concerned guidelines vary from country to country[7]. It is recommended that the absence of suspicious lymph node enlargement indicates a preference for extended two-field thoracoabdominal lymphadenectomy (conventional thoracoabdominal and upper mediastinal lymphadenectomy), whereas, suspicious lymph node enlargement supports the option of three-field cervical and thoracoabdominal lymphadenectomy (cervical and thoracoabdominal lymphadenectomy and upper mediastinal lymphadenectomy)[23]. Furthermore, to investigate the precise lymphatic staging, at least 15 Lymph nodes should be obtained[24]. In recent years, studies have compared two-field approach lymphadenectomy with three-field approach lymphadenectomy for postoperative overall survival (OS) and disease-free survival. The results suggest that there are no significant differences in prognosis between the two approaches[25].

Additionally, studies have shown that lymph node harvest during esophagectomy is associated with improved postoperative survival. A study by Lutfiet al[26] demonstrated that during lymphadenectomy, when 7 lymph nodes were harvested, OS improved significantly, and when 25 Lymph nodes were harvested, it showed maximum OS benefits. Other researchers also came to a similar conclusion regarding the influence of lymphadenectomy on postoperative survival after neoadjuvant therapy;when the number of lymph node dissections reached 25, postoperative life expectancy was the highest[27].

Surgical options for adenocarcinoma of EGJ

Although many studies have compared the transthoracic approach to the transhiatal approach, because of the special anatomical location of EGJA, the optimal surgical option is still under debate and recommendations are inconsistent[7]. Based on 14 studies published over the last 30 years, Tsenget al[28] concluded that the Siewert classification had a significant influence on the surgical options. The transthoracic approach was recommended for Siewert type I EGJA, and extended gastrectomy for Siewert type III EGJA. Siewert type II EGJA can be resected using a transthoracic or transhiatal approach, and each approach has similar effects on surgical results and overall prognosis. The surgical method should be determined according to patient factors, such as risk factors and general condition,and also depends on the preference of the surgeon[28]. The advantages of the transthoracic approach are better mediastinal lymph node dissection and better proximal resection margin, as it has the advantages of better para-celiac and para-aortic lymph node dissection, avoidance of thoracotomyassociated morbidity, and preferable postoperative quality of life[28].

Based on the analysis of the results of the Siewert type II EGJ carcinoma surgical treatment conducted by the JCOG9502 trial, the consensus of Chinese experts suggested that the transhiatal approach is recommended for esophageal invasion < 3 cm, and the right thoracoabdominal two-incision surgical approach is preferred for esophageal invasion ≥ 3 cm[29]. Currently, surgical treatment for true EGJA in Japan is generally determined by esophageal invasion of 3 cm and gastric invasion of the upper onethird as a demarcation[4]. Ivor-Lewis esophagectomy combined with upper or middle mediastinal lymphadenectomy is recommended for esophageal invasion ≥ 3 cm. For esophageal invasion < 3 cm, an extended proximal transdiaphragmatic gastrectomy was performed for distal invasion within the upper third of the stomach, and an extended total transdiaphragmatic gastrectomy was performed for invasion that exceeded the upper third of the stomach; meanwhile, a lower mediastinal lymphadenectomy was also required[4]. Nishiwakiet al[30] proposed that the distance from the EGJ to the proximal margin of the primary tumor (esophageal invasion) could be an indicator of mediastinal lymph node metastasis in Siewert type II tumors. The results showed that a distance ≥ 2 cm in esophageal invasion was associated with a higher risk of mediastinal lymph node metastasis. When esophageal infiltrates reach 3 cm, the risk was even higher, and the transthoracic approach should be considered for upper and middle mediastinal lymphatic dissection[30]. These results are consistent with the guidelines and current surgical options (Figure 1).

The optimum range of lymphatic dissection has not reached a consensus. According to previous studies, for Siewert type III EGJA, the incidence of lymphatic metastasis in groups No. 1, 2, 3, and 7 was higher than 20 %, metastasis in groups No. 5, 6, 11d, and 12a was less than 5 %, and metastasis in groups No. 107, 111, and 112 was much lower and close to zero. Compared with Siewert type III EGJA,the incidence of lymphatic metastasis in Siewert type II EGJA was significantly lower in the abdominal lymph nodes and higher in the lower mediastinal lymph nodes[31].

To date, only retrospective trials have been conducted on the surgical choice of Siewert type II EGJA,and research has not indicated any difference between the two surgical approaches. The CARDIA trial is the first randomized trial to compare transthoracic esophagectomy with transhiatal extended gastrectomy for Siewert type II EGJA, and the trial is ongoing (DRKS00016923). Esophagectomy is expected to achieve better radical resection and thorough mediastinal lymphatic dissection, leading to better OS, while the quality of life is still acceptable[32].

PERlOPERATlVE CHEMOTHERAPY AND RADlOTHERAPY: EXlST CONTROVERSY

Perioperative treatment includes multiple options, among which chemotherapy (CT), radiotherapy(RT), and chemoradiotherapy (CRT) are the most commonly used regimens. Neoadjuvant therapies benefit tumors by reducing tumor volume, tumor stage,etc., and therefore improve the surgical resection rate and prognosis. Postoperative therapies are mainly used to eliminate tumors that have not been completely resected and possible metastases, prolong postoperative survival and reduce the recurrence rate. Over the years, many researchers have made efforts to explore the best perioperative therapy for adenocarcinoma of esophagus and EGJ (Table 1).

RT in adenocarcinoma of esophagus and EGJ

Compared to many other tumors, including gastric carcinoma, RT plays a more important role in the treatment of EAC and EGJA. A Chinese research group included 4160 patients with Siewert type II EGJA to investigate whether perioperative RT benefits patients. The results indicate that neoadjuvant RT improves prognosis in more advanced patients (T3 or with lymphatic metastases) and is more effective in T4 tumors. For stage T1-2, surgery alone is preferred[33]. Furthermore, studies have shown that CRT is superior to RT alone in many aspects, such as tumor downstaging, R0 resection, and pathological complete response (pCR)[34,35], especially in patients with fairly good tolerance for CT. A study analyzed 101 patients with esophageal cancer who underwent CRT or RT alone. The primary endpoints were OS, progression-free survival, local control rate, and toxicity. The results showed that RT was safe and feasible and could partially compensate for the absence of CT[36]. However, because many elderly patients included in the cohort were not eligible for CT, the conclusion has limitations.

CT in adenocarcinoma of esophagus and EGJ

The validity of perioperative CT and concurrent CRT has been widely discussed and is considered thestandard treatment option. Mokdadet al[37] included 10086 patients with EGJ cancer who received adjuvant CT or postoperative observation. Patients who underwent adjuvant CT were relatively younger and more likely to have advanced disease. In the long-term, the OS of patients who received CT was clearly better at 1 year (94%vs88%), 3 years (54%vs47%), and 5 years (38%vs34%). In other words, most patients benefited from adjuvant CT for OS[37]. Another group included 312 patients (210 with EGJA and 102 with EAC) who underwent radical surgery after neoadjuvant CT (nCT). The experimental group received postoperative CT based on ECX (epirubicin, cisplatin, and capecitabine) regimen,while the control group did not. No significant differences were found in the primary prognostic data between the two groups. Only patients with postoperative microscopic residual disease (R1) benefited from postoperative CT[38].

Figure 1 Siewert classification of adenocarcinoma of the esophagogastric junction and recommended surgical options[3,4,28,29]. The tumors that centered 1-5 cm above esophagogastric junction (EGJ) are defined as Siewert type I, transthoracic esophagectomy is recommended. the tumors centered from 1 cm above to 2 cm below the EGJ are Siewert type II. For Siewert type II tumor with esophageal invasion ≥ 3 cm, Ivor-Lewis esophagectomy with upper/middle mediastinal lymphadenectomy is propriate surgical option; for esophageal invasion < 3 cm, extended proximal transhiatal gastrectomy or extended total trashiatal gastrectomy with lower mediastinal lymphadenectomy are recommended according to whether gastric invasion exceeded 1/3 of the stomach. The tumors that centered 2-5 cm below EGJ are defined as Siewert type III and extended total gastrectomy is the optimal surgical option. EGJ: Esophagogastric junction.

The purpose of nCT in tumor downstaging is to facilitate resection and improve the postoperative prognosis. Compared with the clinical stage before nCT, the tumor stage after nCT is more closely associated with prognosis and eligibility for surgery[39]. For borderline resectable cancers of the esophagus and EGJ, neoadjuvant therapy is usually recommended, followed by evaluation of the tumor stage according to the guidelines. Davieset al[39] reported that patients who received neoadjuvant therapy had a lower local recurrence rate (6%vs13%) and systemic recurrence rate (19%vs29%), along with improved survival. Predictors of postoperative survival after nCT have also been discussed. The results showed that pT staging, pN staging, and resection status were strong predictors of survival,including patients who underwent surgery alone or who received neoadjuvant therapy. Patients who achieved R1 resection or pT3/4 stage after neoadjuvant therapy had better OS than those who achieved the same outcome after surgery alone[40]. In addition, the adverse effects associated with neoadjuvant therapy, also known as toxicity, require attention. Buntinget al[41] reported 67 (23.4% of 286 cases)patients who experienced toxicity during nCT. Toxicity can lead to adverse consequences, such as failure to complete CT (47%vs17%), loss of opportunity for surgical resection (17.9%vs7.8%), and poor OS (median survival of 20.7 movs37.8 mo). Even if patients who missed surgery were excluded,median survival was shorter in patients with toxicity responses (26.2 movs47.8 mo)[41].

CRT in adenocarcinoma of esophagus and EGJ

Perioperative concurrent CRT is widely used to treat EAC and EGJA. The INT0116 trial, the first randomized controlled study of postoperative adjuvant CRT for gastric and EGJ carcinoma, showed that postoperative 5-FU and tetrahydrofolic acid combined with RT significantly extended OS and relapsefree survival in patients with advanced gastric and EGJ carcinoma[42]. This illustrates the importance of CRT in perioperative adjuvant therapy. Currently, adjuvant CRT is the standard treatment for gastric and EGJ carcinoma in the United States[43]. The CROSS study conducted by a Netherlands group in 2015 concluded that the OS of the long-term follow-up of 368 patients with resectable esophageal or EGJ carcinoma benefited more from neoadjuvant CRT (nCRT) followed by surgery than surgery alone. For patients with adenocarcinoma, the median OS of the group that received nCRT plus surgery was 43.2 mo, longer than 27.1 mo of the group that received surgery alone. Therefore, nCRT followed by surgery could be considered the standard treatment for patients with resectable locally advanced EAC or EGJA[44]. The importance of nCRT in the treatment of esophageal and EGJ carcinoma has been widely recognized. After sufficient evaluation of perioperative treatment options, the American Radium Society gastrointestinal expert panel established appropriate criteria that recommended nCRT for patients with resectable non-metastatic EAC or EGJA, cT3 or lymphatic metastasis, and high-risk manifestations. In patients with pathological evidence of lymphatic metastasis without neoadjuvant treatment, adjuvant CRT is recommended[45].

Compared with surgery alone, CT and CRT promote the survival of patients with EAC and EGJA.However, whether CRT is superior to CT remains under debate. Among the 13738 patients with EAC and EGJA who received nCT or nCRT and eventually underwent surgery, patients who underwent nCRT were 2.7 times more likely to achieve pCR than those who underwent nCT; however, OS was not statistically different[46]. Similarly, many studies have shown that nCRT is associated with a higher pCR rate, higher R0 resection rate, lower lymphatic metastasis rate, and is more likely to achieve downstaging before surgery than nCT; however, previous studies have not been able to reveal the effect on postoperative survival[35,47,48]. Several studies have suggested improvements in postoperative survival in patients treated with nCRT compared with those treated with nCT. Smythet al[49] showed a 4% increase in the 3-year OS in patients who received adjuvant CT after CRT plus surgery. Since most recurrent EGJAs occur within three years after surgery, this may indicate an increase in the curative ratio and that postoperative CT improves survival even after neoadjuvant therapy[49]. In another study of 170 patients with Siewert type II/III EGJA, Liet al[50] showed that nCRT provided better survival and improved R0 removal and pCR rates more than nCT in patients with locally advanced EJGA.However, Tianet al[51] drew the opposite conclusion after retrospectively reviewing 1048 patients with gastric adenocarcinoma and EGJA who underwent preoperative CT or CRT. While perioperative CRT was associated with a higher pCR rate (13.1%vs8.2%), preoperative CRT appeared to increase the risk of mortality[51].

In addition to the effectiveness of nCRT, its adverse effects and impact on the postoperative quality of life are also factors that must be considered. In the postoperative follow-up, a total of 386 patients with EAC who underwent surgery alone or nCRT plus surgery were followed up for 105 mo. Although the physical function and frailty of the patients remained relatively low, no adverse effects on long-term health-related quality of life (HRQoL) were observed in patients with preoperative nCRT. This finding supports the application of nCRT in patients with EAC[52]. Other similar trials conducted by the same group showed a significant reduction in HRQoL, but eventually HRQoL returned to baseline within eight weeks[53], and nCRT had no significant effect on postoperative HRQoL compared with patients who received surgery alone[54]. That is, nCRT did not cause irreversible long-term changes in HRQoL,which confirmed the safety of nCRT.

Further, there has been some discussion regarding the timing of surgery after neoadjuvant therapy.The current routine is 4-6 wk. Nilssonet al[55] randomly assigned 249 patients with esophageal or EGJ cancer into two groups: standard timing of surgery (4-6 wk) or prolonged timing of surgery (10-12 wk).The primary endpoint was overall postoperative complications, and the secondary endpoints were severity of complications, 90-d mortality, and inpatient stay. Data analysis showed that the timing of surgery after nCRT had no significant effect on short-term prognosis[55], while a meta-analysis in 2018 suggested a different opinion. A total of 15086 patients from 13 studies were included. Enrolled patients were divided into two groups based on the time of surgery (shorter or longer than the 7-8 wk interval).A subgroup analysis of patients with adenocarcinoma did not show significant differences in pCR rates,and a prolonged interval was significantly associated with increased mortality. An extended interval was also detrimental to the 2-year and 5-year OS[56].

Furthermore, researchers have compared the prognosis of patients with EAC after surgery alone and in combination with neoadjuvant therapy to clarify whether current treatment strategies could obtain any benefit. Although many patients are predicted to benefit from neoadjuvant therapy, their responses to therapy vary. It is estimated that the total restricted mean survival time would have a 7% gain if optimal therapy was applied instead of actual therapy[57]. This suggests that individualized treatment could benefit patients the most, but how to select individuals with better reactions to specific treatment options and achieve such benefits remains to be further studied.

DEFlNlTlVE CRT: FOR UNRESECTABLE TUMORS

At diagnosis, tumors in a considerable proportion of patients are no longer indicated for surgery because of tumor invasion of vital organs, main vessels, or nerves (T4b) or the occurrence of distant metastasis (M1)[5]. Neoadjuvant therapy might achieve tumor downstaging in some cases; however, for patients who refuse surgery or have unresectable tumors, definitive CRT (dCRT) remains the only option[23]. With the improvement in concurrent CRT, the 5-year survival of patients with unresectable tumors significantly improved from 0-14% to 20%-25%, indicating that the aim was transformed from palliative to efficient treatment[58]. It was about three decades ago when dCRT first attracted attention.Early randomized trials have shown that the median survival and 5-year survival of patients who received CRT were superior to those who received RT alone[59], and subsequent research confirmed the superiority of CRT over RT[58].

Locoregional recurrence was the main cause of treatment failure in patients who underwent dCRT. In a retrospective study of 184 patients with esophageal carcinoma, locoregional recurrences occurred in 41% of the cases, mostly within 12 mo after cessation of dCRT, and almost all occurred in 24 mo. Among the cases that recurred at the primary tumor site, only 57% occurred within the scope of radiation,which suggests that RT is valid in reducing locoregional recurrences[60]. However, the therapeutic doses of dCRT are still under discussion. In a cohort study, 12638 patients with metastatic esophageal cancer were divided into three groups: CT alone, combined with palliative RT, and combined with definitive RT. The median OS of the patients treated with CRT was 11.3 mo for the definitive dose radiation group and 7.5 mo for the palliative dose group. Thus, in CRT, compared to a lower dose of radiation, patients benefit more from definitive dose radiation[61]. In contrast, another study compared RT of standard dose with high dose in dCRT, which enrolled 260 patients with esophageal cancer. The results showed that the 3-year local progression-free survival rates were 70% and 73%, respectively,which suggested that higher doses of RT did not necessarily improve the clinical outcome, as assumed[62]. Therefore, the current recommended dose of radiation for dCRT benefits clinical outcomes more than higher or lower doses.

CONCLUSlON

Surgery has long been the only radical treatment available for EAC and EGJA. In recent decades, with the development of various other techniques as well as the concept of MDT, increased treatment options could be applied in patients with EAC or EGJA. There is no doubt that surgery is always one of the most important treatments; however, it is no longer the only solution. Clinicians with MDT teams can tailor the regimens for patients. At the same time, more options face more challenges. There are still many controversies, such as the optimal treatment for specific patient groups and the proper timing for applying certain treatments. Moreover, the implementation of MDT is also problematic because not every region or medical center can perform every treatment independently. It is worth exploring and discussing how to make MDT a useful and efficient method to guide treatment. It should be clarified that the final goal is to provide a standardized, efficient, and individualized treatment to each patient to improve OS and quality of life.

FOOTNOTES

Author contributions:Zheng YH wrote the manuscript; Zhao EH reviewed and revised the manuscript; and both authors proofed the manuscript.

Conflict-of-interest statement:The authors have nothing to disclose.

Open-Access:This article is an open-access article that was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution NonCommercial (CC BYNC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is noncommercial. See: https://creativecommons.org/Licenses/by-nc/4.0/

Country/Territory of origin:China

ORClD number:Yi-Han Zheng 0000-0003-2664-0535; En-Hao Zhao 0000-0003-1112-0043.

S-Editor:Yan JP

L-Editor:A

P-Editor:Yan JP

World Journal of Gastroenterology2022年31期

World Journal of Gastroenterology2022年31期

- World Journal of Gastroenterology的其它文章

- Duodenal-jejunal bypass reduces serum ceramides via inhibiting intestinal bile acid-farnesoid X receptor pathway

- Preoperative contrast-enhanced computed tomography-based radiomics model for overall survival prediction in hepatocellular carcinoma

- Prevalence and clinical characteristics of autoimmune liver disease in hospitalized patients with cirrhosis and acute decompensation in China

- Application of computed tomography-based radiomics in differential diagnosis of adenocarcinoma and squamous cell carcinoma at the esophagogastric junction

- Radiomics and nomogram of magnetic resonance imaging for preoperative prediction of microvascular invasion in small hepatocellular carcinoma

- Insights into induction of the immune response by the hepatitis B vaccine