One-step laparoscopic pancreatic necrosectomy verse surgical step-up approach for infected pancreatic necrosis: a case-control study

Sheng-bo Han, Ding Chen, Qing-yong Chen, Ping Hu, Hai Zheng, Jin-huang Chen, Peng Xu, Chun-you Wang, Gang Zhao

1 Department of Emergency Surgery, Union Hospital, Tongji Medical College, Huazhong University of Science and Technology, Wuhan 430022, China

2 Department of Pancreatic Surgery, Union Hospital, Tongji Medical College, Huazhong University of Science and Technology, Wuhan 430022, China

Corresponding Author: Gang Zhao, Email: gangzhao@hust.edu.cn

KEYWORDS: Infected pancreatic necrosis; One-step laparoscopic pancreatic necrosectomy; Surgical step-up approach

INTRODUCTION

Acute pancreatitis is a common and potentially fatal disease worldwide, with an incidence rate of 34 cases per 100 000 person-years.Approximately 20% of acute pancreatitis patients develop pancreatic or peripancreatic necrosis.Most of them are sterile, but 30% are infected. Infected pancreatic necrosis (IPN) is the leading cause of death in acute pancreatitis and is a difficult treatment point, with a very high mortality rate of 30%-39%.Clinical practice and various studies have shown that surgical intervention has an irreplaceable position in the treatment of IPN.

In the treatment guidelines for IPN ten years ago, laparotomy debridement was the golden standard operation. Still, a large number of clinical studies had shown that the incidence of serious complications such as new organ failure, sepsis, abdominal hemorrhage, and the gastrointestinal fistula was relatively high after laparotomy, leading to the unsatisfactory success rate of IPN treatment.In 2010, van Santvoort et alreported that a step-up approach based on minimally invasive surgical techniques was used to treat IPN for the first time. The multi-center randomized trials showed that the incidence of new organ failure, hernia, and secondary diabetes after the step-up approach was significantly lower than that of laparotomy. The core strategy of the step-up approach was that patients underwent percutaneous catheter drainage (PCD) first. Then video-assisted retroperitoneal debridement (VARD), minimal access retroperitoneal pancreatic necrosectomy (MARPN), or minimally invasive percutaneous nephoscopy necrosectomy were performed if necessary.

However, it should be noted that the step-up approach often requires multiple interventions, and they might not be effective for IPN patients with multiple abscesses. In addition, some IPN patients do not have a suitable route for PCD. Considering the rapid advancement of laparoscopic technology, we have conducted the one-step LPN as a minimally invasive method for these IPN patients since 2015. Through the preoperative imaging system assessment, a personalized laparoscopic approach, including omental sac approach, mesenteric root approach, paracolic sulci approach, or combination of multiple approaches, was conducted according to the location of the lesion. Therefore, we conducted a case-control study to investigate whether the one-step LPN was the same safe and eff ective as the surgical step-up approach (SSUA) in the treatment of IPN patients.

METHODS

Study design and population

All the IPN patients underwent one-step LPN and SSUA in the Department of Emergency Surgery of Wuhan Union Hospital from January 2015 to December 2020 were enrolled. Severe acute pancreatitis was diagnosed according to the Revised Atlanta Classification (2012) of acute pancreatitis.IPN was diagnosed by the positive culture of tissues obtained from the fineneedle aspiration, or the appearance of gas in the necrotic collections on contrast-enhanced computed tomography (CECT). This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Huazhong University of Science and Technology.

Inclusion criteria

(1) Confirmed IPN patients; (2) patients who underwent one-step LPN or SSUA in Wuhan Union Hospital from January 2015 to December 2020; (3) patients with age ≥ 18 years.

Exclusion criteria

(1) Patients who had previous intervention (percutaneous, endoscopic, or surgery) for necrotizing pancreatitis; (2) patients with chronic pancreatitis at an acute stage.

Follow-up

LPN approach

The approach and method of LPN were determined by multidisciplinary experts (including radiologists, physicians, and pancreatic surgeons) based on the location and state of the necrosis that CECT showed. LPN was performed by the experienced pancreatic surgeon. After general anesthesia, the patient was placed in a supine position; the surgeon inserted the trocar according to the position of the abscess cavity, and then established pneumoperitoneum. (1) In the omental sac approach, the surgeon pulled the stomach upwards, and the assistant pulled the transverse colon downwards to expose the gastrocolic ligaments fully. The gastrocolic ligament was opened through the avascular area and the omental sac was entered. The surgeon operated along the stomach wall to avoid damage to the colon. The surgeon removed the necrotic pancreatic tissue, drained the pus, flushed the abscess cavity, and placed two drainage tubes in each abscess cavity. It is mainly suitable for IPN when the abscess cavity is located near the head of the pancreas or the duodenum (supplementary Figure 1). (2) In the mesenteric root approach, the assistants pulled the colon transversum and fully expose the mesentery; the surgeon opened the mesentery between the middle and left colonic arteries. Then the surgeon conveniently removed the necrosis in the tail of the pancreas (supplementary Figure 2). (3) In the paracolic sulci approach, the patient was placed in a suitable position, and the assistant gently pushed the intestine to expose the necrosis cavity beside the abdominal wall. Next, the surgeon opened the lateral peritoneum to remove the necrosis (supplementary Figure 3). (4) For patients with multiple abscesses cavities, a combination of multiple approaches was performed (supplementary Figure 4). The images of the one-step LPN are shown in supplementary Figure 5.

Irrigation was conducted for patients with poor drainage. Drainage irrigation with saline (0.9%) was performed from the fourth day after operation. In the first week, continuous lavage at a rate of 100 ml/h was performed, entering a deeper drainage tube and draining through a shallow drainage tube. After the first week, the frequency of lavage was reduced to 500 mL twice a day. When the CT scan showed that the residual abscess cavity was significantly reduced and the drainage was clear, lavage was stopped. The drainage tube was taken out when the abdominal CT scan indicated no residual abscess.

Percutaneous catheter drainage

PCD was conducted under the guidance of CT. The patient was placed in the supine position for a CT scan to determine the lesion’s size, location, and puncture route. Routine disinfection, draping, and local anesthesia were performed. Puncture was performed with a 21-23 G fine needle, the patient was instructed to breathe deeply and hold breath, then resume breathing after the punch. The needle core was withdrawn and 1-3 mL of diluted contrast agent was injected through the needle sheath to confirm the drainage area’s size, shape, and position. An 18 G needle was used to insert at the same position. After the needle reached the predetermined depth, the needle core was removed, and the trocar was used to aspirate the effusion. The drainage fluid was drawn out, taken a small amount for related laboratory testing. Finally, the drainage tube was inserted to drain the liquid, and the drainage bag was connected and fixed by suture. When the patients’ condition improved, the LPN was performed.

Surgical step-up approach

The surgical step-up was performed and the details had been described previously.Briefly, PCD was conducted firstly; VARD, MARPN, or open surgery were conducted for patients who did not improve.

General treatment

All patients received enteral nutrition through nasojejunal feeding. When enteral nutrition couldn’t meet the required caloric intake, parenteral nutrition was given. All patients were treated with broad-spectrum antibiotics according to guidelines,and appropriate antibiotics were selected based on bacterial culture. Routine post-operative treatment was carried out according to the principle of Enhanced Recovery After Surgery (ERAS).

Data collection

Short-term complications included new-onset multiple-organ failure, intraabdominal bleeding, enterocutaneous fistula, perforation of a visceral organ, new-onset infection, pancreatic fistula, additional pancreatic necrosectomy, new-onset SIRS, and newonset admitted to ICU. Long-term complications included new-onset diabetes and the use of pancreatic enzymes. In addition, the imaging, medication, and laboratory results of patients were collected from the electronic medical records.

如前文的分析思路,选取贷款申请被接受的企业数据为样本,进行广义结构方程模型分析,以检验银行信任对小微企业贷款抵押要求的影响。详细分析结果如表6所示。

Statistical analysis

All continuous data were shown as means ± standard deviation or median with quartile and analyzed by t-test or Mann-Whitney U test. Dichotomous data were analyzed with the Chi-square test or Fisher’s exact test. Firstly, a univariate logistic regression was performed on each variable. The factors with P<0.1 in the univariate analysis were extracted for the multivariate analysis. Both directions of the maximum likelihood estimation method were used to screen the independent variable. Factors with P<0.05 were enrolled into the regression model. The statistical analysis was conducted with R software.

RESULTS

A total of one hundred fifty-three IPN patients were diagnosed as IPN in the Department of Emergency Surgery of Wuhan Union Hospital from January 2015 to December 2020, of which 93 patients were eligible (Figure 1). Fiftyfour patients underwent one-step LPN and 39 patients underwent the SSUA. One patient in the one-step group and two patients in the surgical step-up group were lost to follow-up.

There was no significant difference in the baseline characteristics of the patients between the one-step and step-up groups (Table 1). However, compared with the step-up group, the time to surgery from the onset of pancreatitis or hospitalization was significantly shorter in the one-step group. Thirty-eight (71.7%) patients had a single abscess cavity and fifteen (28.3%) patients with two or more abscess cavities in the one-step group (<0.05); while thirty-four (91.9%) patients had a single abscess and three (8.1%) patients with two or more abscess cavities in the step-up group (<0.05). We found that the leading cause of IPN was gallstone (43.3%), followed by abuse of alcohol (20.0%). Infection of(25.6%) was the most common gramnegative bacteria, followed by(11.1%). Infection of Enterococcus (16.7%) was the most common gram-positive bacteria, followed by(12.2%).

Three patients in the one-step group and three patients in the step-up group were converted to laparotomy because of extensive dense adhesions. Nine patients in the step-up group were cured by PCD and without surgery. The mortality and the incidence of short-term complications or long-term complications had no significant diff erence between these two groups (Table 2). However, the total length of stay was significantly shorter in the one-step group (24 [17-35] d) than that in the step-up group (31 [21-45] d). The major complications occurred in 8 (15.1%) patients in the onestep group and 7 (18.9%) in the step-up group (P=0.848). There were 3 (5.6%) patients in the one-step group and 2 (5.4%) patients in the step-up group death (P=0.999). The incidence of new-onset multiple organ failure (MOF) was 4 (7.5%) in the one-step group and 4 (10.8%) in the step-up group (P=0.712). New-onset SIRS and pancreatic fistula were the most common complications in both groups.

Figure 1. The flowchart of the cohort of infected pancreatic necrosis patients. IPN: infected pancreatic necrosis; PCD: percutaneous catheter drainage.

Table 1. Baseline characteristics of the patients

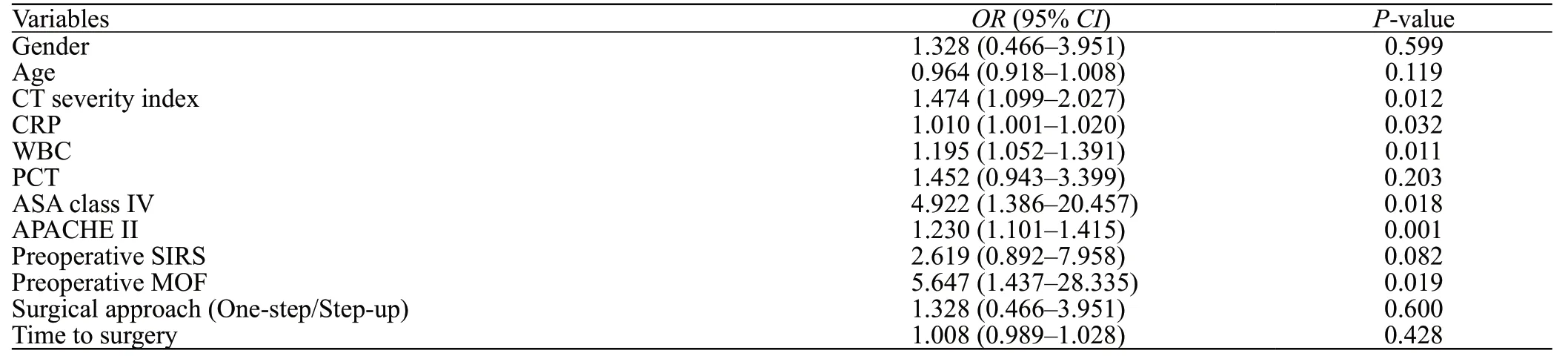

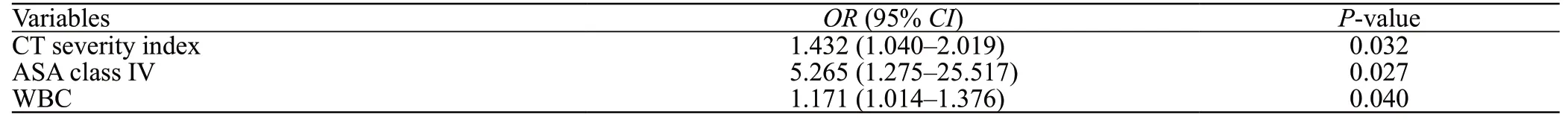

We performed logistic regression analysis to find the risk factor for major complications or death. Univariate logistic regression showed that the CT severity index, ASA class IV, APACHE II, preoperative MOF, CRP, and WBC at admission were related to the death or major complications, but the surgical approach (one-step/stepup) was not the risk factor (Table 3). Multi-factor logistic regression analysis indicated that CT severity index (odd ratio [OR]=1.432, 95% confidence interval [CI]: 1.040-2.019), ASA class IV (OR=5.265, 95% CI: 1.275-25.517), and WBC (OR=1.171, 95% CI:1.014-1.376) were the independent risk factors for death or major complications (Table 4).

DISCUSSION

This case-control study demonstrated that the onestep LPN was not superior to the SSUA in terms of mortality, short-term complications, and long-term complications in the treatment of IPN patients. However, our data showed that the total hospital stay in the onestep group was significantly shorter than that in the surgical step-up group. In our study, the tertiary referral IPN patients accounted for 58.9%, and we performed one-step LPN for IPN patients with multiple abscesses or no safe route for PCD.

The mortality and incidence of major complications were similar in the one-step LPN and SSUA. Laparotomy was the golden standard operation for IPN in the past.But now, it had become an alternative treatment when other minimally invasive interventions were failed. In 2010, van Santvoort et alreported that a step-up approach based on minimally invasive surgical techniques was used to treat IPN for the first time. They indicated that the incidence of new organ failure, hernia, and secondary diabetes after the stepup approach was lower than that of laparotomy. Many studies have reported that minimally invasive surgery based on the step-up model was better than traditional open surgery.Many guidelines recommended that the surgical treatment of IPN should follow the step-up treatment strategy.In our study, the incidence of new-onset MOF, intraabdominal bleeding, enterocutaneous fistula, perforation of a visceral organ, new-onset infection, and death had no significant diff erence between the one-step group and surgical stepup group.

There was no significant diff erence in the incidence of the pancreatic fistula between the one-step group and surgical step-up group, which was lower than that in the previous study using the SSUA but higher than the endoscopic approach.The reasons for the diff erence might as follows. First, 58.9% of patients were a tertiary referral, and their general condition was stable. Second, our sample size was relatively small. There was a total of 93 patients in our study. However, 47 patients met the exclusion criteria due to acute flare-up of chronic pancreatitis, previous drainage or surgery. Therefore, it might reduce the incidence of postoperative pancreatic fistula.

With the development of endoscopic technology and the application of new materials, some surgeons directly drained or removed the pancreatic necrotic tissue through natural cavities such as the stomach or duodenum, which were called endoscopic transluminal drainage (ETD) or endoscopic transluminal necrosectomy (ETN).Bakker et alfound that ETN reduced the incidence of postoperative inflammation, MOF, and pancreatic fistula, also improved the survival rate of patients when compared with surgical intervention. In a multicenter randomized controlled study, van Brunschot et alcompared the efficacy of the SSUA and endoscopic step-up approach (ESUA) in the treatment of IPN. They indicated that although there was no significant diff erence between SSUA and ESUA in terms of major complications and mortality, the ESUA group had a lower incidence of pancreatic fistula and a shorter hospital stay. Moreover, Bang et alreported in a randomized controlled study that ESUA could significantly reduce the incidence of major postoperative complications of IPN when compared with SSUA, and decrease treatment costs and improve quality of life. They suggested that the endoscopic step-up model had a good application prospect in treating IPN. However, the successful implementation of the ESUA required that the pancreatic necrotic tissue was close to the gastric cavity, which was fully liquefied and relatively wrapped. In addition, due to the technical and equipment requirements and the high cost, we did not perform the ESUA in our center.

Table 2. Outcome of the patients

Table 3. Univariate logistic regression analysis

Table 4. Multivariate logistic regression analysis

In our study, there was no significant diff erence in the incidence of new-onset diabetes and pancreatic exocrine insufficiency in the two groups. In a retrospective analysis of Stanford University Medical Center, Worhunsky et alreported the incidence of new-onset diabetes and new-onset pancreatic exocrine insufficiency of laparoscopic transgastric necrosectomy for IPN was 10% and 20% in a long-term follow-up. Cao et alshowed that the incidence of new-onset diabetes and pancreatic exocrine insufficiency of laparoscopic-assisted necrosectomy for IPN was 6.1% and 2.2%, respectively. In line with the previous studies, our results showed that the incidence of long-term complications was similar and low both in the one-step group and surgical step-up group.

The total length of stay of the one-step group was significantly shorter than that of the surgical stepup groups (P<0.001). Our result was in accordance with a recent study.They indicated that one-step laparoscopic-assisted necrosectomy for selected IPN patients could shorten the median length of hospital stays when compared with step-up laparoscopicassisted necrosectomy. The SSUA requires multiple interventions, while one-step LPN only needs one operation in most cases. Therefore, compared with the SSUA, one-step LPN significantly reduced the length of stay of IPN patients.

Univariate logistic regression showed that the surgical approach (one-step/step-up) was not the risk factor for major complications or death. Multivariate logistic regression analysis indicated that CT severity index, ASA class IV, and preoperational WBC were the independent risk factors. Hollemans et alreported that male sex, MOF, percentage of pancreatic necrosis, and the heterogeneous collection were negatively correlated to successful PCD for IPN patients. Cao et alshowed that preoperative CRP and IL-6 were independent risk factors for at least three interventions in IPN patients undergoing one-step or step-up surgery. Bang et alreported that acute physiology scores were a risk factor of major complications or death based on a COX proportional hazards model.

With the constant development of laparoscopic technology, some surgeons attempted to treat IPN with LPN.In a retrospective analysis from China, Tu et alreported that the mortality rate of retroperitoneal laparoscopy for IPN was 6%, the incidence of major complications was 28%, and the incidence of secondary surgery rate was 17%. In a retrospective analysis of Stanford University Medical Center, Worhunsky et alreported that the mortality rate of laparoscopic transgastric necrosectomy for IPN was 5% and the incidence of major complications was 24%. In a retrospective study from India, Mathew et alreported that the mortality rate of LPN for IPN was 4%, the incidence of pancreatic fistula and conversion to laparotomy was 29% and 7%, respectively. Our result also showed that the mortality and incidence of major complications or long-term pancreatic insufficiency were low in the one-step LPN approach.

Compared with the SSUA or ESUA, one-step LPN has many advantages. (1) It is safe and effective to sweep the necrotic tissues within the mesenteric root, paracolic sulci, or pelvic, which are not available to access the appropriate puncture route. (2) LPN could expediently remove the necrotic tissue for IPN patients with multiple abscesses, demonstrating the similar eff ect of the laparotomy pattern. (3) The visual field of LPN is significantly better than that in the minimally invasive or ESUA. The high-resolution magnified video output of the laparoscope would be conducive to visually distinguish the boundary between necrotic tissue and normal tissue. (4) The step-up approach often requires multiple debridements, which might prolong the length of stay and exaggerate physical and psychological stress. On the contrary, one-step LPN could timely remove the necrotic tissue for IPN patients. (5) The catheter is placed under laparoscopic guidance, thereby, the post-operation drainage is more accurate. Meanwhile, LPN requires the establishment of pneumoperitoneum, which limited its application for IPN patients who cannot tolerate. The therapeutic eff ect of LPN needs to be further confirmed by relevant clinical studies.

Our study has some limitations. First, this was a casecontrol study, and the level of evidence was not high enough. Although we adopted strict inclusion and exclusion criteria, there were still some selection biases. Second, the sample size of our study was relatively insufficient, which may overestimate the safety and effectiveness of one-step LPN. Therefore, a multi-center study of one-step LPN for IPN should be carried out later. Third, this study lacked the data on the ESUA for the treatment of IPN patients. We will take it into our research when our hospital can routinely perform the ESUA.

CONCLUSIONS

Due to the complexity of IPN, the treatment should be a highly individualized comprehensive treatment. For IPN patients, it is necessary to grasp the indications and timing of surgical intervention strictly, and cannot be restricted to a fixed mode. In summary, we conducted a case-control study and found that the one-step LPN was the same safe and eff ective as the SSUA in the treatment of IPN patients. Moreover, one-step LPN could significantly reduce length of stay when compared with the SSUA. Given the current high mortality rate of IPN, it is still the mission of clinicians to explore the pathogenesis of IPN, the optimal treatment time, and the intervention patterns.

Funding: This work was supported by the Clinical Research Physician Program of Tongji Medical College, Huazhong University of Science and Technology.

Ethic approval: This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Huazhong University of Science and Technology.

Conflicts of interest: The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Contributors: SBH and GZ conceived, designed, and revised this article. JHC, PH, DC, and CYW designed and drafted this article. SBH, QYC, HZ, and PX acquired and analyzed the data. These authors contributed equally: SBH, JHC, PH, DC.

All the supplementary files in this paper are available at http://wjem.com.cn.