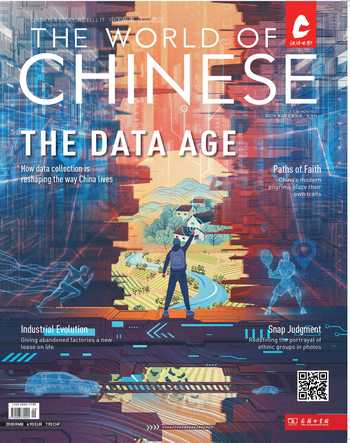

The Data Age

Digital Covid-19 health codes, facial recognition payment options, autonomous vehicles on the streets, AI-powered irrigation systems, farms with 5G networks—from “smart cities” to “future villages,” the digital revolution in China is very much underway. But big data brings with it big problems. Private companies harvest mountains of data on citizens without mature legal or technical guidelines for protecting it, health codes appear to have been manipulated by local officials, rural areas have pumped more money into public surveillance software than technology to improve grain yields, while “smart cities” laud over high-tech gimmicks that fail to solve practical problems like inadequate public transport. A small number of people have even had enough, ditching smartphones and embracing a life offline.

It may be too late to turn back the clock on the digitization of Chinese society, but equally the efficient digital utopia promoted by giant tech firms and grand government plans seems a long way off. Whether embrace or reject new digital technologies, Chinese citizens face a swath of uncertainties navigating a big data future.

從“智慧城市”到“数字乡村”,中国数字化浪潮如火如荼。与此同时,数据安全、配套技术与法律也迎来全新挑战。我们将面对什么样的数字未来?

Illustration and Design by Cai Tao and Fengzheng yisheng, Photographs from VCG

Digital Dilemma

Can people secure their data and privacy in the digital age?

Tian Li is sure her smartphone spies on her.

To her, the evidence is clear: “Often, once I mention something in chats with friends or search for it in the browser or other apps on my phone, Taobao will soon feed me ads for relevant products or services…this happens on JD and other apps too,” Tian explains, referring to Chinas two biggest e-commerce services. Her friends have had the same experience, she claims.

After this discovery early this year, Tian, a Shanghai resident in her 30s who wished to use a pseudonym in this story, has been on guard against any apps requests to access functions on her mobile phone, including the microphone and photo album—unless its required to activate a platform she really needs.

Similarly, Li Ao, an employee at an e-commerce company in Chengdu, Sichuan province, only allows access to his data when he uses the apps. “Most apps require access to the contact list and album, even though I dont see any connection between the accessibility and their function. You have to accept the terms they impose in order to use them,” he complains.

Their concerns are well-founded. For the last year or so, Chinas regulators have been on the case of technology firms relentless harvesting of data. According to an announcement by the Cyberspace Administration of China (CAC) this July, Chinese ride-hailing giant DiDi has collected perhaps billions of pieces of data from a dozen categories of users and drivers information, including screenshots from users photo albums, information from their clipboards and app lists, facial recognition images, age, occupation, kinship, and addresses, and drivers education and ID information. DiDi reportedly failed to clarify the purpose of collecting 19 of these items of personal information.

The company was fined over 8 billion yuan (approximately 1.2 billion US dollars) for its “severe” and “abominable” (in the words of the CAC) violations of Chinas Cyberspace Security Law, Data Security Law, and Personal Information Protection Law; while its CEO Cheng Wei and president Liu Qing were fined 1 million yuan each.

Meanwhile, a 2018 report released by the China Consumers Association showed that 91 out of the 100 common apps it surveyed request “excessive” information from users, including 59 apps asking for users location, 28 requesting contact lists and identity information, and 22 requesting mobile phone numbers. Others asked for access to users photo albums, financial information, biometrics, occupation, transactions, and online browsing records.

The public have been increasingly concerned with their privacy and data security, struggling to negotiate between the convenience brought by new technologies and devices, and their side effects, including excessive or illegal collection of data, leaks and illegal trade of data, and consequent spam messages, scams, and other risks. This concern has only heightened during the Covid-19 pandemic, when more personal information has been exposed due to digitalized anti-epidemic efforts.

“The illegal collection and abuse of data has gotten worse,” as the country goes digital, while relevant laws and regulations are yet to catch up, observes Zhao Yong, a computer science professor from the University of Electronic Science and Technology of China. As co-founder of the Big Data Center at Tsinghua University Suzhou Automotive Research Institute (which Zhao claims to be Chinas first professional big data research institute) and an associated company to promote research and application of relevant technologies since 2012, Zhao has closely observed the countrys digital development over the last decade, as data has become a new factor of production.

In the 21st century, data has also become a strategic resource vital to the nations economy. As Chinese President Xi Jinping put it during a visit to the China Academy of Sciences in July 2013: “The vast ocean of data, just like oil resources during industrialization, contains immense productive power and opportunities. Whoever controls big data technologies will control the resources for development and have an advantage.” In the following year, the Chinese government included big data in its government work report for the first time, and officially launched its “big data strategy” in 2015, aiming to harness data to boost the economy.

According to the latest statistics released during a press conference by the CAC this August, the size of Chinas digital economy, driven by technologies such as big data, cloud computing, and artificial intelligence (AI), grew from 11 trillion yuan in 2012 to 45.5 trillion yuan in 2021, accounting for 39.8 percent of the countrys GDP—up from 21.6 percent in 2012. This helped China rank second in the world for size of digital economy.

The digital trend has swept every aspect of peoples lives: In 2021, around 85.2 percent of personal consumption in the shopping sector was online, as well as 78.6 of consumption in the catering sector, 66.7 percent in culture and entertainment, over 50 percent each in travel, accommodation, and transportation, according to a report issued last May by the Institute of Quantitative & Technological Economics at the Chinese Academy of Science.

Zhao compares big data to a “microscope,” as it can analyze all the information companies gather to tailor their services to different customers accurately. “[The companies] may know you better than yourself…When you browse online and like some bag or clothes [even] subconsciously, the algorithm will feed it to you promptly,” he explains. As the algorithm and data can be transformed into economic returns through targeted selling and marketing, some apps have gone to extremes of breaking laws to collect as much information as possible, adds Zhao.

This has its upsides. “Its convenient. [Online shopping websites] can recommend products tailored to my needs, such as my favorite style and design of clothes,” says Wen Yun, a graduate student from Maoming, Guangdong province, who has turned to platforms like Taobao and Pinduoduo to buy up to 90 percent of her daily necessities since high school.

However, Tian believes the disadvantages outweigh the benefits. “To some extent, it narrows down our choices and makes our world one-dimensional,” she observes, referring to how apps repeatedly recommend the same products and types of content to her, rather than anything fresh. “I have a cat and sometimes watch pet-themed short videos. The platforms then bombard me with videos of various pets, even exotic marmots.”

Another reason for Tians skepticism is her discovery of being “ripped off” by Taobao in late 2020: When she and her boyfriend (who seldom uses Taobao) browsed on the platform respectively for a new food dehydrator, her results were dominated by products costing around 300 yuan, over 100 yuan higher than her boyfriends; it took her quite some time to dig out the cheaper options when browsing from her own account.

She believes the platform has restricted her access to more economically-priced products, due to her being less sensitive to prices in previous transactions.

Price discrimination on online platforms, or “big data ripping off frequent customers (大數据杀熟),” has been a common consumer complaint around businesses apparent misuse of big data. In a report issued by the Beijing Consumer Association this May, over 64 percent of the 4,163 users surveyed said they had experienced price discrimination. The study included 18 popular apps and websites including Taobao and Pinduoduo, online travel platforms Trip.com and Qunar.com, and food delivery giants Meituan and Ele.me.

In Chinas first lawsuit over price discrimination last year, a VIP member on Trip.com surnamed Hu in Shaoxing, Zhejiang, sued the platform for charging her 2,889 yuan a night for a hotel room that actually cost only 1,377 yuan. She thought the platform raised the price by taking advantage of users past consumption habits, while the platform argued that the price rose that night due to high demand but limited room vacancies. Although the court ruled in Hus favor and ordered the platform to pay her 4,777.48 yuan in compensation (three times the price difference), it did not support her price discrimination claim due to insufficient proof.

Zhao Zhanling, a lawyer specializing in IT and copyright from Beijing (no relation to Professor Zhao), tells TWOC that to find convincing evidence for such a claim, one must have access to the companies servers, and has to check the algorithm, data, and other internal management documents, which is seldom possible for ordinary consumers.

Another major issue is the security of the data collected. According to statistics from China Internet Network Information Center, more than 221 million online users in the country have had their personal information leaked. Some 16.6 percent had been scammed, 9.1 percent had had their devices infected with malware, and 6.6 percent reported their accounts or passwords stolen in 2021. Telecommunication network frauds in 2020 alone caused a loss of over 35 billion yuan, Li Ruiyi, deputy chief judge of the Third Court of the Supreme Court, told news site Jiemian in June 2021.

According to Professor Zhao, this data could be shared with the platforms associated parties or traded on the black market. But as individuals information is exposed to so many parties in each online transaction—for instance, to the e-commerce platform, shop owner, express delivery company, and delivery person for an online purchase—its difficult to track who is responsible for the leaks.

Even the authorities can be a source of information leaks and misuse, especially since the outbreak of Covid-19, the response to which has seen residents information such as their travel histories collected and disclosed in the name of anti-pandemic purposes. Some property management companies have even required residents to fill in their educational background, marital status, and WeChat account name, in addition to name, phone number, and address, when applying for an access pass to their residential compounds.

According to a survey by the Southern Metropolis Daily in March 2020, only 20 percent or so of all the respondents knew how their information collected through Covid-19 health codes by residential communities, supermarkets, pharmacies, and public transport would be stored and used after the pandemic.

The disclosure of information, including the address of suspected and confirmed Covid-19 cases, can have significant consequences. For instance, during a surge of Covid-19 cases in Chengdu last December, a 20-year-old girl known as “Miss Zhao” was abused online for her visits to several bars before she was sent to hospital as a confirmed case. Netizens quickly discovered her personal information, including ID number and address.

Wen, in Guangdong, had a similar experience: after she was quarantined on September 2 as a “close contact” with a confirmed case, she was bombarded with harassing WeChat messages and phone calls from strangers. Days earlier, she had been required to fill in her phone number, ID number, and address in the WeChat groups of her residential community and quarantine hotel, consisting of over 550 members in total.

“We could easily see all other members information on that document [on WeChat], including their phone number and address,” the college student recalls, adding that she had been concerned about this method of information collection at the time, but no one else questioned it.

This summer, several municipal officials in Zhengzhou, the capital city of Henan, were punished for having instructed the local big data bureau, health code management team, and a local big data company, to switch the Covid-19 health code of 1,317 people from “green” to “red” in mid-June, thus restricting their movements. But, it was alleged, these citizens had not contracted Covid-19—they had deposited money at four Henan banks that had halted withdrawals due to cash flow issues, and the codes were changed supposedly to prevent the irate customers from gathering and protesting in the city.

Similarly, in July, local residents committees in Changping district, Beijing, required residents coming back from Covid-19 risk areas to wear electronic bracelets to track their temperature during their home-stay quarantine, with the app associated with the device able to access the wearers location, camera, microphone, and contact list. Both incidents sparked public outcry and discussion over privacy.

Professor Zhao points out that the root cause for all these issues is that “ownership of data has been transferred from users to platforms and companies,” who then often process the data without informing users about how they collect, store, and use it, and may “choose to ignore or violate relevant rules and laws, because to comply with those rules will cost them a lot and impact their algorithm, services, and revenue.”

The Personal Information Protection Law implemented last November represents a milestone in Chinas data privacy laws. It details general rules for personal information processing, individuals rights, and the responsibilities of data-collectors. For instance, personal information must be collected for clear and reasonable purposes and be used for the stated purposes with minimal impact on an individuals rights and interests; only the minimum information necessary should be collected; and individuals must be notified and must give consent before their information is processed.

On Weibo, Lawyer Zhao hailed its implementation as the start of a “new age” of personal information protection, citing examples that many apps, including Alipay, have revised their personal information or privacy policies, and strengthened their compliance and protection of data.

However, tracking and regulating the millions of apps in China will prove difficult, and stricter laws like the European Unions General Data Protection Regulations (GDPR) would “rein in the development of the digital economy,” Xu Caisu, a researcher at Shanghai University, told Xinmin Weekly last July.

Nonetheless, public awareness of digital information and privacy protection is on the rise, and many people are taking things into their own hands. Tian avoids using her real name on deliveries from online shopping websites (though she still must register for them with her ID card), and regularly uninstalls apps and clears her browsing history online to reduce her data footprint. To avoid price discrimination, she compares prices on different shopping platforms.

However, after much trial and error, she knows that, with her smartphone seemingly always spying on her, “no matter how I try to compare, Ill never find the best-value goods.”– Tan Yunfei (譚云飞)

Huaweis new data center in Guizhou province: IT giants in China usually have their own data center

An anti-fraud app launched by the Ministry of Public Security last year went viral

Courier packages, labeled with the recipients name, phone number, and address, are a common low-tech way for personal information to leak

Data Farming

Can “digital villages” fulfill their promise to modernize the countryside through technology?

In the spartan surroundings of his office, Zhao Lin surveys the village streets on a giant computer screen. On this “magic mirror” are images beamed to him from over 200 CCTV cameras, some with infrared capabilities, via the villages speedy fiber-optic broadband network, which can alert Zhao to potential traffic accidents, crime, and natural disasters, as well as the growth of crops and prevalence of pests in the fields.

“Every year before, there were thefts and fights between villagers, but through the construction of this network, we were able to reduce the incidence of these crimes,” Zhao, the deputy Party secretary of Shuangshi village, located in Sichuan province, boasts to TWOC. And when hes not observing the screen, the 34-year-old browses a smartphone app where villagers can record their concerns using wireless internet from one of the areas seven 5G base stations. “We want to build an interactive bridge between the village committee and the villagers,” he says.

Zhao believes digital technologies like the “Magic Mirror Smart Eyes” hold the key to securing a prosperous future for villages. So does Chinas central government: Since 2019, when the State Council issued the “Digital Village Development Strategy Outline,” it has promoted the development of “digital villages” throughout the country. The plan is for rural areas to have fast internet, 5G coverage, telemedicine facilities, high-tech agriculture run on big data, e-commerce, and “smart” finance, government, elderly care, and tourism that run on the latest digital innovations, so that urban and rural residents can enjoy equal access to public services.

But even with vast investment in digital infrastructure in places like Shuangshi, massive hurdles remain before Chinas villages are dragged into a modern digital future. Though internet coverage now reaches even some of the remotest parts of the country, many villagers still struggle to use and understand online services, especially the elderly who make up nearly 25 percent of rural residents. Promises of booming sales in e-commerce and vast returns from “Taobao Villages” have failed to materialize in much of the countryside.

Meanwhile, technology for public security and surveillance is sometimes prioritized over improvements that might bring other benefits to villagers. In Shuangshi, the village committee is first focusing on “public governance” (it took eight months to install all the cameras needed for the Magic Mirror) before moving onto “smart agriculture,” according to Zhao.

Nonetheless, digital access is expanding rapidly in rural areas. By the end of 2020, for example, over 98 percent of villages in China had 4G network coverage, while internet penetration to rural areas rose from around 34 percent in 2017, to 57.6 percent in 2021. Online retail sales in rural areas reached 2.05 trillion yuan last year, up from just 180 billion yuan in 2014, according to statistics from the Ministry of Commerce and the state-affiliated China Internet Network Information Center (CNNIC).

Zhaos village has seen rapid digitization over the last two years. “The village was the first in Sichuan to achieve full 5G coverage, and then full fiber-optic [broadband] coverage,” he claims. Hes also got big plans to connect the village via the Internet of Things (IoT) with “remote weather sensors, water quality sensors, soil sensors, and pest sensors” all transmitting data seamlessly to the village committee “so that we can understand the environmental situation of the village.”

But most villages remain far from the digital rural utopia envisaged in government plans. “The smartphone penetration rate in rural villages is high; this is not a problem,” says Gu Yizhen, associate professor of economics at Peking Universitys HSBC Business School, “but how to use it...[especially] for old people: thats a problem.” He cites as an example his father, who does not know how to use WeChat or Alipay, and “probably wont feel comfortable paying for something first before getting the products.”

Xiao Wei, an agricultural researcher at Southwest University of Science and Technology, tells TWOC that digital agriculture technologies are too expensive for most farmers. Hi-tech, hi-definition cameras and monitoring devices could, in theory, be “available to every village…[but] if you dont have the large scale to support this kind of platform, then its not very meaningful,” says Xiao. “If youre just a small-scale farm…theres no point” since farmers can monitor small plots themselves without spending on technology. Digital farming technologies, therefore, are mainly reserved for big agriculture companies and local governments.

In Shuangshi, the elderly “dont understand or embrace this [digital technology]...because they have low exposure,” Zhao admits. “Some of them dont even have smartphones.” In response, Zhao and his colleagues have established a “comprehensive service station” in the village where local officials and volunteers are on hand to help seniors use digital technologies for errands such as applying for their pensions online.

This year, Zhao explains, new rules require elderly pensioners to prove they are still alive, by uploading photos and videos of themselves to an app, in order to continue receiving their benefits. Many seniors in the village struggle with this process, or simply dont have a smartphone, so head to the service station where they can receive help from officials.

Digitizing villages is also costly. Anding village in Zhejiang province has spent over 1 million yuan to turn itself into a “social media check-in spot” and was selected as one of the pilot areas for the provinces first batch of “future villages,” according to Farmers Daily. The village opened a campsite in May this year and invested in a WeChat mini-program which tourists can access via QR codes around the village to check how busy the site is, whether there are parking spaces available, see hiking routes, and buy local tea products. However, as Covid-19 restrictions and regular outbreaks across the country disrupt travel and tourism, its unclear how sustainable this model will prove to be.

Zhao tells TWOC that the added costs of all the digital projects in Shuangshi village so far, including the Magic Mirror system, come to more than 2 million yuan. Since the annual budget for the village committee is just 110,000 yuan, nearly all this funding has come from technology firms, mostly China Telecom, a giant state-owned telecommunications company. “The [governments] ‘revitalization of the countryside plan is shifting the attention of the whole of society to the countryside...so big companies like China Telecom have plans to push their business and technology into rural areas,” says Zhao, explaining the companys eagerness to fund rural projects.

Zhao calls Shuangshi village an “experimentation lab” in which some technologies and projects will inevitably fail, but he hopes some will become sustainable long term. The villages next digital project is to develop “smart fishing,” deploying sensors in farmers ponds to measure and adjust water temperature, and pH and oxygen levels.

The sensors connect to smartphones, and Zhao hopes to help farmers avoid losses from fish dying in the summer due to low oxygen levels in water, a common phenomenon in the village which can cause “tens of thousands of yuan in damage overnight.” Normally, farmers must observe the fish to check for signs of danger, but “human experience is not accurate enough, and at night everyone has to sleep,” says Zhao, explaining the benefits of the digital system.

The system will cost around 10,000 yuan for farmers to install, plus a monthly service fee—a significant outlay for fish farmers who make around 60,000 to 80,000 yuan profit a year on a typical onemu(0.16 acre) pond. Farmers are enthusiastic to at least see the technology in action, according to Zhao, and over time he hopes the cost will come down as more people take it up and find it leads to higher profits.

“The farmers in the countryside are middle-aged or older; between 40 and 70 years old...so they are not so enthusiastic to embrace digital technology,” Zhao admits. “But they arent averse to it, as long as it can bring them some economic value [and] bring them some benefits, then they are willing to use it.”

For larger farms, technology can be helpful, argues Xiao. “The software can send data on pests directly to them, and automatically tell them what the pest is, how many there are, and how long theyve been there.” Then the farm management or village committee can decide how to deal with it. At the national level, such systems can help government bureaus to monitor disease and pest outbreaks among crops and notify farms on the ground to take precautions, Xiao explains.

Besides agriculture, some villages have invested heavily in promoting e-commerce to put more money into residents pockets. But while online retail has boomed overall, some rural areas are seeing gains reversed. In a research paper published in 2021, Gu Yizhen and colleagues found that projects to connect rural areas to e-commerce failed to help villagers sell their products, nor did they have any significant impact on average incomes in the 100 villages they studied in Anhui, Henan, and Guizhou provinces.

E-commerce in villages risks becoming a race to the bottom as platforms encourage more villagers to sell, leading to competition between neighbors who try everything to cut costs and must spend on ads to compete. Gu argues “logistics cost is the major barrier to adopting e-commerce in villages,” citing lack of postal services and high transportation costs in rural areas. Furthermore, “on Taobao, only [products on] the first or second page can attract the attention from consumers…so you cannot expect every village to sell all its own products online.”

Not all villages are suited to becoming so-called “Taobao Villages” (defined by Alibaba as villages with at least 10 million yuan e-commerce sales annually and at least 100 online shops on Taobao run by local residents). In Guizhou province, for example, 13.73 million yuan of funding allocated to e-commerce projects for 106 villages remained unused in 2018 due to a lack of practical projects and insufficient e-commerce skills among residents, according to a paper by researchers from Australian National University published in 2021.

Despite all the investment and improvement in digital technologies in rural areas, there is still a vast gap to cities. In 2021, the rural internet penetration rate was 57.6 percent, compared to 81.3 percent in urban areas, according to the CNNIC. When schools closed during the pandemic, rural students suffered disproportionately because many of them struggled to participate in online classes due to poor internet coverage or phone reception.

In Shuangshi, however, Zhao believes the future is bright. “Lets think about smartphones, right? Twenty years ago, it would hardly have been possible for everyone to have a smartphone…So new products like this are very expensive to develop in the early stages,” he says, drawing an analogy to the new digital technologies he is trying to promote in his village. “We hope that one day in the near future, these digital village solutions, like our smartphones today, can be used by everyone…every village, to help community governance and services, and agricultural development.”– Sam Davies

Alibabas “Rural Taobao” project aims to bring cheap products to rural areas, but has struggled to help farmers sell their products online

Farmers have flocked to livestream services to sell their products as the Covid-19 pandemic has blocked many offline selling channels

Shuangshi village aims to become a pioneer in digital technology

Digital Hermits

Living smartphone-less in China in the digital age

Zheng Si doesnt call himself a “hermit” from data, “or I would not have seen your friend request,” he says, when he greets TWOC on WeChat, before moving the conversation to Telegram, a platform with a reputation for stronger data protection.

However, Zheng, an architect in training in Europe who wants to use a pseudonym to maintain his digital anonymity, tries to reduce his reliance on the digitized world. In 2017, while many of his peers were enjoying the increasingly telepathic product recommendations of e-commerce platforms like JD and Taobao, Zheng deleted both.

That year, he graduated from a liberal arts college and returned to his native Beijing to teach at a secondary school. He was shocked by how differently his students interacted with technology, compared with his own generation. In one class, Wu assigned groups of students a task to summarize an article, only to see the teens and preteens take out their own laptops, messaging each other online in silence. “They were sitting right next to each other,” he says. “But only on the computer did they feel comfortable talking to each other.”

This incident made Zheng reflect on how the digitized world can assimilate into the real world. “Technology itself is neither good nor bad,” Wu reflects. “If you use it well, it works for you and wont swallow you up; but if you abuse it, you become its slave.”

What doesnt sit well with him is big datas propensity to “flatten” complex human emotions into abstract data points. “For example, if you read something and you find it amazing, you click on the ‘like button. That means your appreciation can be represented by a logical symbol,” he explains.

Zheng believes giving up shopping on JD and Taobao helped him regain agency over human experiences, such as by rediscovering supermarkets and corner shops in his physical community. Once, he had needed foam sheets to make an architecture model, but couldnt recall where to buy them, because his shopping experience had become so disconnected from physical locations. Finally, he recalled going to a “Golden Five Star Wholesale Market” in Beijings Haidian district as a child.

Zhengs trip to Golden Five Star informed him of a new problem. Since 2016, the almost 20-year-old market, which used to host thousands of shops and stalls selling spare parts and other hard-to-find wholesale items, gradually closed down. The change is often attributed to a city-wide operation eliminating what the government called “low-end” physical markets, but Wu suspects the competition with online sellers who can operate at a lower cost also contributed to its decline.

Zheng had to reinstall WeChat, which he also deleted in 2017, due to the Covid-19 pandemic. The lack of a health code, a program embedded in WeChat that grants people entry into public buildings, had made his non-digital life even harder. Before the pandemic, hed asked people to send him text messages via SMS. “I probably lost a lot of opportunities to develop friendships,” he says with a shrug.

For news, Zheng relies on an RSS subscription to a few websites, and between his work projects, hanging out with friends, reading, and thinking, he says he does not have a lot of time left for internet and social media. “Sometimes I do go online to watch movies for 10 hours in a row, then I turn it off,” he says.

Zheng respects the hardcore defenders of data security who allegedly refuse to scan any health codes and sue businesses that dont accept cash, but he believes a “confrontational approach” might not be the most effective way to bring back more balance to digitization. He likens the progression of big data to “a sinking ship we are all on,” seeing the trend as irreversible. “Just expressing ‘I dont like it wont stop the sinking.”

As an architect, Zhengs ambition is to create spaces for offline communities, and provide more lifestyle options in addition to the digital world people are increasingly used to. “Some people are already making this come true,” he says, citing Shanghais Big Fish Community Design Center, which designs urban spaces to facilitate participatory offline events and hangout spots like cafes, book bars, and family play areas for local residents.“[These endeavors] might actually help people realize that life offline is much more colorful than online,” he says.

Every morning, 66-year-old Wu Juxin takes two buses from her apartment in southwest Beijing to get into the bustling Chaoyang and Dongcheng districts, where she cleans homes for dozens of clients.

On these two-hour journeys, while many of her fellow commuters are glued to their phone screens, Wu just stares out the window.

Unlike youngsters who may have deleted chat or e-commerce apps to make a statement on big data, Wu is not a deliberate “digital hermit”—she simply doesnt have a smartphone.

The only place she shops at is the farmers market near her home, where the vendors accept cash, and surprisingly, she hasnt faced many inconveniences, despite the notorious pandemic controls. When she needs to enter an apartment complex to clean, “You sign in at the gate and show your ID. For buses, just swipe the bus pass,” Wu explains.

She is rarely turned away, provided she follows Beijings Covid testing protocol (a negative result within 72 hours of entry, at the time of writing). Usually, one would pull up ones own results via the “Health Kit” mini-app on WeChat or Alipay, but its also possible to get someone else—say, a security guard at the entrance of a park—to look up a persons results by entering their national ID number in their own Health Kit.

When security guards at one apartment complex in the Sanlitun neighborhood refused her entry for a lack of health code this May, Wu got the police involved. After the officers verified her information, they ordered the apartments management company to make accommodations for people who are not digitally connected. “From then on, as long as you have an ID card, you can get into [that community],” Wu says, proud of her victory.

Wu has been working in Beijing for 30 years since she left her hometown in rural Feidong county, Anhui province, to earn money to raise her two young sons. “There are a lot of house cleaners, migrant workers, and elderly people who cannot read, just like me,” Wu says, explaining why a smartphone would not necessarily make everyones life easier.

Her daily rounds take her between home, the market, buses, and a handful of clients communities. She never eats out or goes to movie theaters, so she doesnt have to worry about showing her health code or leaving a digital footprint there. “Im too stingy. If I have onefen, I would cut it in half before using it,” she jokes. She doesnt even visit free parks, as she has almost no free time because of work.

In recent years, many domestic workers have turned to the internet to look for work: apps that connect cleaners to clients, WeChat groups where contractors share gigs, or agencies which attract customers with discounts on review app Dianping.

But Wu has been able to sustain a busy schedule solely by word-of-mouth recommendations. “[Clients] trust me as honest and thorough,” she beams, “so they all introduce me to their friends. I used to have so many requests that I often had to turn them down.”

Covid-19 has seen an exodus of expats from Beijing, who make up most of Wus clientele. Shes found her monthly income dropping from 8,000 to 9,000 yuan to only half that. “If there are no more gigs, Ill move back to Anhui,” she says, now that her sons have grown up and there is less pressure, before asking TWOC to recommend her to more clients.

Wherever she goes next, Wu sees no appeal in getting there with a smartphone. “If you dont have one, you are fine. But once you do, youll feel you have to use it. And when you use it, theyll check your phone, while they could have just checked your ID,” she explains. “Using a smartphone is actually more trouble.”– Siyi Chu (褚司怡)

A 76-year-old man who doesnt own a smart phone pays his parking fees by cash at Beijings China World Trade Center

A sign with a QR code outside of Beijings Tuanjiehu Park: Visitors are expected to scanto register with their Health Kit upon entering

New Cities, Old Problems

Smart cities are yet to truly transform urban life

Ten years since China launched 90 pilot “smart cities,” the technologically advanced, AI-powered, efficiently and digitally governed metropolitan utopias that technology companies and local governments promised are mostly yet to materialize.

Millions of yuan have been pumped into an estimated 800 smart city projects since then, but though there are more cameras with more digital functionality than ever, 5G coverage is almost everywhere, and many government services have gone online, most Chinese cities still suffer from the same problems as cities around the world: bad traffic, packed public transport, growing inequality, and environmental degradation.

This is not for a lack of cash or digital infrastructure. Alibabas “City Brain” project in Hangzhou, where the company is headquartered, uses AI to help optimize traffic systems, ensure quicker response times by ambulances, and automatically monitor traffic violations. DiDiChuxing, on the other hand, has launched self-driving vehicle pilot projects in Shanghai and Changsha. Shenzhen became the first city to pilot the Peoples Bank of Chinas digital Renminbi in 2020. Accounting firm Deloitte estimates investment in smart cities in China amounts to 25.9 billion US dollars up to 2018, and predicts that that will rise to 40 billion by 2023. China is responsible for over half of the worlds smart city projects, yet according to the 2019 Global Smart City Index, only two mainland Chinese cities are in the top 100 for their “smartness”: Shanghai (at 93rd) and Beijing (99th).

Lack of long-term planning and a focus on flashy tech over more practical solutions are part of the problem. In a 2021 study of smart cities, researchers at Peking University, Lanzhou University, and the Zhejiang Academy of Commerce found that Chinese smart cities scored well for “smart governance,” which includes things like public security and online government services, but lowest on “smart environment” and “smart economy” metrics. They argued that “technocentrism” driven by technology firms responsible for building the smart cities, and local governments who blindly recruit them and follow their plans, “does not pay enough attention to people-oriented application services.” Instead, it focuses on transportation, energy, and infrastructure at the expense of healthcare and residents needs like clean water, air, and food.

Some have accused local governments of rushing into contracts with big technology firms without proper strategies for how digitalization, AI, and the Internet of Things can be practically employed to improve the standard of living. Many of these technologies rely on massive amounts of data collected from residents, yet due to a lack of standard rules for data storing, different government bureaus often have trouble sharing information. Smart city plans have also been accused of a copy-and-paste approach which fails to consider the unique needs and advantages of different cities. Meanwhile, others worry that smart cities focus too much on high-cost technologies that will exclude those on low incomes, worsening the digital divide between rich and poor, and between rural and urban residents.

Building a new city from scratch might seem like an attractive alternative to tackling engrained problems in big cities like Beijing and Shanghai. Xiongan, a new smart city in Hebei province that has been under construction since 2017, is meant to become a model of smart, green, efficient urban life by 2035. So far, ecological projects have expanded vegetation coverage in two districts of the city by around 30 percent, according to a 2020 study. A new high-speed railway connection to Beijing and Tianjin, and a new station, have been built at a cost of around 33 billion yuan.

Yet for now, most of Xiongan remains a construction site, populated mainly with low-skilled workers and farmers. If it is to be a high-tech hub near the capital, then how, or even whether, these people fit in is still a puzzle. Chinas smart cities will need to become smarter at allocating resources to be deemed a success. – Sam Davies