Bidirectional relationships of physical activity and gross motor skills before and after summer break:Application of a cross-lagged panel model

Ryan D.Burns*,Yang Bai,Wonwoo Byun,Taylor E.Colotti,Christopher D.Pfledderer,Sunku Kwon,Timothy A.Brusseau

Department of Health,Kinesiology,and Recreation,University of Utah,Salt Lake City,UT 84112,USA

Abstract

Keywords:Children;Motor competence;Physical activity;Schools

1.Introduction

Physical activity(PA)has numerous health and wellness benefits for children that span the physical,cognitive,and affective domains.1-5Unfortunately,many children in the United States do not meet the recommended 60 min of PA per day guideline,and PA behaviors tend to decline as children track into adolescence.6-8To improve PA,school-and community-based interventions have been devised to improve the number of PA opportunities.9,10These interventions have been implemented with varying success in diverse pediatric population subgroups,11including in children from lowincome families,where the environment presents barriers to participation.12Using data from the 2017-2018 National Survey of Children’s Health,25.3%of 10-17-year-old youths from families at the 0-99%of the U.S.Federal Poverty Level met PA guidelines.13Because children spend most of their weekdays in school settings,and because of the out-of-school PA barriers that children from low-income families experience,school hours may provide valuable opportunities for children to participate in PA.14However,during prolonged out-of-school time periods such as summer break,unhealthy behaviors can lead to unwanted fitness loss and weight gain,which can compromise further PA participation and lead to PA disengagement as children return to school.15-17

Gross motor skills are considered to be an important correlate of PA18-20and have also been found to be longitudinally associated with weight status.21Fundamental gross motor skills are building blocks for more advanced and complex movements,and they comprise locomotor skills(e.g.,running,jumping,hopping)and object control/ball skills(e.g.,throwing,catching,kicking).22Complex movements needed for sports participation and leisure PA require a level of motor competency,defined as the ability to perform gross motor skills in a proficient manner.23Stodden et al.24derived a framework linking gross motor skills to PA and metabolic dysfunction.This relationship has been studied using various moderators and mediators of effect,such as specific psychosocial variables and specific domains of health-related fitness.25-29Motor development researchers have also postulated that the link between gross motor skills and PA may be bidirectional,depending on a child’s developmental stage.20,24,26,27

In the United States,studies examining trends in weight status and fitness have shown that summer break may be a barrier to optimizing health behaviors.Brusseau et al.30found that unfavorable changes in weight status and cardiorespiratory endurance occurred over summer break and that sports participation moderated the relationship between summer break and fitness loss.Fu et al.31found that significant losses in health-related fitness improvements accrued during a Comprehensive School Physical Activity Program after a summer break.Other researchers have found accelerated weight gain over the summer.32,33Brazendale et al.34derived the Structured Days Hypothesis to provide a framework for these observed phenomena.According to the hypothesis,children tend to be more active and consume more healthful food during structured days such as school days,and they tend to be less physically active and consume more highly caloric foods during unstructured days such as summer break.34These general trends have been observed in other studies showing accelerated weight gain during the summer.35However,longitudinal studies have found higher PA during the weekends compared to weekdays,possibly suggesting that the decreases in PA and increases in weight status may be specific to summer break or specific to prolonged school breaks.36

Studies empirically testing bidirectional relationships between PA and gross motor skills are limited.Understanding this potential bidirectional relationship over summer break can provide critical information for developing interventions that are aimed at attenuating declines in PA as children track through elementary school.Furthermore,examining these relationships may be important in children from low-income families,who may have additional PA barriers compared to their counterparts in higher socioeconomic strata.12,37To the best of our knowledge,no study has examined the bidirectional relationships between school PA and gross motor skills over a summer break.Therefore,the purpose of this study was to examine the bidirectional relationships between school PA and pt?>gross motor skills over a 3-month summer break in a sample of children from low-income families.It was hypothesized that the relationship between PA and gross motor skills is bidirectional over summer break,with higher PA predicting higher gross motor skills and higher gross motor skills predicting higher PA from the end of the spring semester to the beginning of the following fall semester.

2.Methods

2.1.Participants

The sample consisted of 440 elementary school-aged children(age=8.9±1.2 years,mean±SD;229 girls)recruited from 3 low-income schools located in the Mountain West region of the United States.All students were recruited from the same urban school district,and the same sample of students was analyzed at 2 separate timepoints.Given the information provided on the school district’s website,91%-94%of the students at each school came from low-income families,characterized as receiving free or reduced-price lunches.Socioeconomic information was not collected at the student level.Study participation exclusion criteria included any healthrelated condition that precluded or limited daily PA participation.Students excluded from the study(3 students)were not included in the sample.Students were recruited from first through fourth grades.The sample distribution per grade level included 79 first graders,88 second graders,121 third graders,and 152 fourth graders.Approximately 61.2%of the sample was of Hispanic/Latino ethnicity,13.9% were Pacific Islanders,11.1%were Caucasian,8.5%were African American,3.1%were Asian,and approximately 2.2%were classified as other.Written and signed consent was obtained from the students,and written and signed consent was obtained from the parents prior to data collection.The University of Utah Institutional Review Board approved the protocols employed in this study(IRB_00078226).

2.2.Measures

2.2.1.Anthropometry

Height and weight were collected in a private room during each child’s physical education class.Height was measured to the nearest 0.01 meters using a stadiometer(Seca 213;Seca North America,Chino,CA,USA),and weight was measured to the nearest 0.1 kilogram using a medical scale(Tanita BD-590;Tanita,Tokyo,Japan).Body mass index(BMI)was calculated using standard procedures,taking a child’s weight in kilograms divided by the square or his or her height in meters.BMI z-scores were calculated using the STATA(StataCorp.,College Station,TX,USA)“zanthro”package via the BMIfor-age 2000 Centers for Disease Control and Prevention growth chart.38

2.2.2.School PA

School-day step counts were measured using Yamax Digi-Walker CW600 pedometers(Yamasa Tokei Keiki,Tokyo,Japan).Yamax DigiWalker models have been shown to provide an accurate recording of steps within±3%of actual steps39and have been shown to be a valid assessment of free-living physical activity.40Pedometers were the instrument chosen for the assessment of PA because of their cost-effectiveness and easily interpretable output(i.e.,step counts)within the context of school PA.Pedometers were worn for 5 consecutive school days between the hours of 8:00 a.m.and 3:00 p.m.and were worn on the right side of the body,at waist level,and in line with the right kneecap.Only school-day PA was assessed;therefore,step counts were recorded only for 7 h per school day.A typical school day at each school consisted of 1 daily 15-min recess period and 1 daily 30-min lunch period.Physical education classes were held once per week for 50 min at each school.Each pedometer had an identification number that was labeled with each child’s name,which was recorded on an Excel spreadsheet.The step-count unit of analysis was average steps per school day.

2.2.3.Gross motor skills

The Test for Gross Motor Development,3rd edition(TGMD-3)was used to assess gross motor skills.The psychometric properties of the TGMD-3 have been reported recently to have acceptable levels of reliability and validity.41-43The TGMD-3 assesses gross motor competency across 13 movement skills within separate locomotor and ball-skill subtests.The total score for the locomotor subtest is 46,the total score for the ball-skill subtest is 54,and the total possible TGMD-3 score is 100.Locomotor skill test items consisted of running,galloping,hopping,skipping,horizontal jumping,and sliding.Ball-skill test items consisted of 2-handed and 1-handed striking,dribbling,overhand throwing,underhand throwing,catching,and kicking.Each child performed the test items across 2 trials that were scored based on 3 to 5 binary-scored and specific performance criteria(0=did not perform correctly;1=performed correctly).Data used for analyses were the total TGMD-3 scores,the locomotor subtest scores,and the ball-skill subtest scores.One member of the research team collected locomotor information at each school,and 1 member of the research team collected ball-skill information at each school to maintain testing consistency.Intraobserver and interobserver reliability were tested on a third-grade class.The intraclass correlation coefficient=0.91 for intraobserver agreement and 0.90 for interobserver agreement,both of which were considered acceptable.

2.3.Procedures

School-day steps and gross motor skills were collected at 2 timepoints:at the end of spring semester immediately before summer break(T1)and at the beginning of the subsequent fall semester immediately following summer break(T2).Data were collected at the end of the 2015-2016 academic school year and at the start of the 2016-2017 academic school year.T1 and T2 were separated by a 3-month summer break during which the children did not attend school.At both timepoints,BMI,step counts,and gross motor skills were assessed on separate and consecutive school weeks during each child’s physical education class.BMIs were collected during the first school week,school step counts were collected during the second school week(averaged across 5 consecutive school days),and gross motor skills were collected during the third school week.This testing order was the same for each child and was scheduled because of the data collection time allocation given to the researchers by school administrators and physical education teachers.Children with missing data at the fall timepoint(n=25;14 girls)because of absence from their physical education classes were contacted at a later date for testing(within 2 weeks of the original testing date).After contact,8 children(4 girls)were successfully rescheduled for testing;therefore,17 children(10 girls)had missing data at the fall timepoint(n=423 at T2).

2.4.Data analysis

The primary variables used in the analysis included average T1 and T2 school-day step counts,T1 and T2 gross motor skill total scores,and T1 and T2 gross motor skill subtest scores(i.e.,locomotor skills and ball skills).T1 and T2 BMI z-scores and the child’s age at T1 were covariates.School step counts,in addition to the total and subtest TGMD-3 scores,were screened for outliers using box-plots and were checked for Gaussian distributions using k-density plots.

The primary analysis consisted of cross-lagged panel models using Full Information Maximum Likelihood,which uses all cases within an analysis,regardless of any missing data.Cross-lagged models can analyze reciprocal relationships between 2 or more observed variables measured at 2 or more distinct timepoints,including both autoregressive effects(the association of a variable on itself at a later point)and cross-lagged effects(an association of a variable with another variable at a later point)within the model.44In our study,cross-lagged models resembled structural equation models,specifically path models,in which all variables were observed(i.e.,no latent variables).Models were constructed using STATA’s(StataCorp.)“sem builder”.Specific paths within each cross-lagged model included T1 to T2 school step counts,T1 to T2 gross motor skills,T1 school step counts to T2 gross motor skills,and T1 gross motor skills to T2 school step counts.Standardized covariance coefficients between T1 school step counts and gross motor skills and between T2 school step count error and gross motor skill error were also computed.Cross-lagged models were adjusted for T1 age and BMI z-scores by correlating T1 age and T1 and T2 BMI zscores with all other variables in the model at both timepoints.The school level was not used as a higher level because of the limited number of clusters(n=3).Analyses were run for the total sample,within sex-specific groups,and for the separate TGMD-3 locomotor and ball-skills subtest scores;therefore,5 age-and BMI-adjusted cross-lagged models were constructed.Reporting of the results included the standardized regression coefficients(β-coefficients)with corresponding 95%confidence intervals(95%CIs).Equation-level goodness-of-fit statistics were computed and reported as the coefficient of determination(R2),in addition to the Bayesian Information Criterion(BIC)and Akaike Information Criterion(AIC).Alpha level was originally set at p<0.05 but was adjusted to p<0.01 because of multiple comparisons.All analyses were conducted using the STATA Version 15.0 statistical software package(StataCorp.).

3.Results

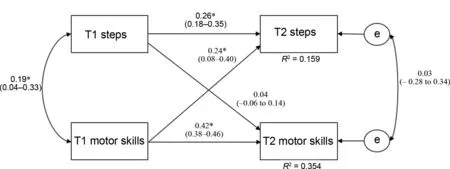

Fig.1.Cross-lagged model of the bidirectional relationships between school-day step counts and gross motor skills before and after a 3-month summer break using the total sample.Model is adjusted for T1 age,body mass index z-scores,and clustering of students within classrooms at T1.T1 stands for timepoint 1-before summer break;T2 stands for timepoint 2-after summer break;e stands for error.Path coefficients are standardized with 95%confidence intervals.*denotes a statistically significant path coefficient at p<0.01.

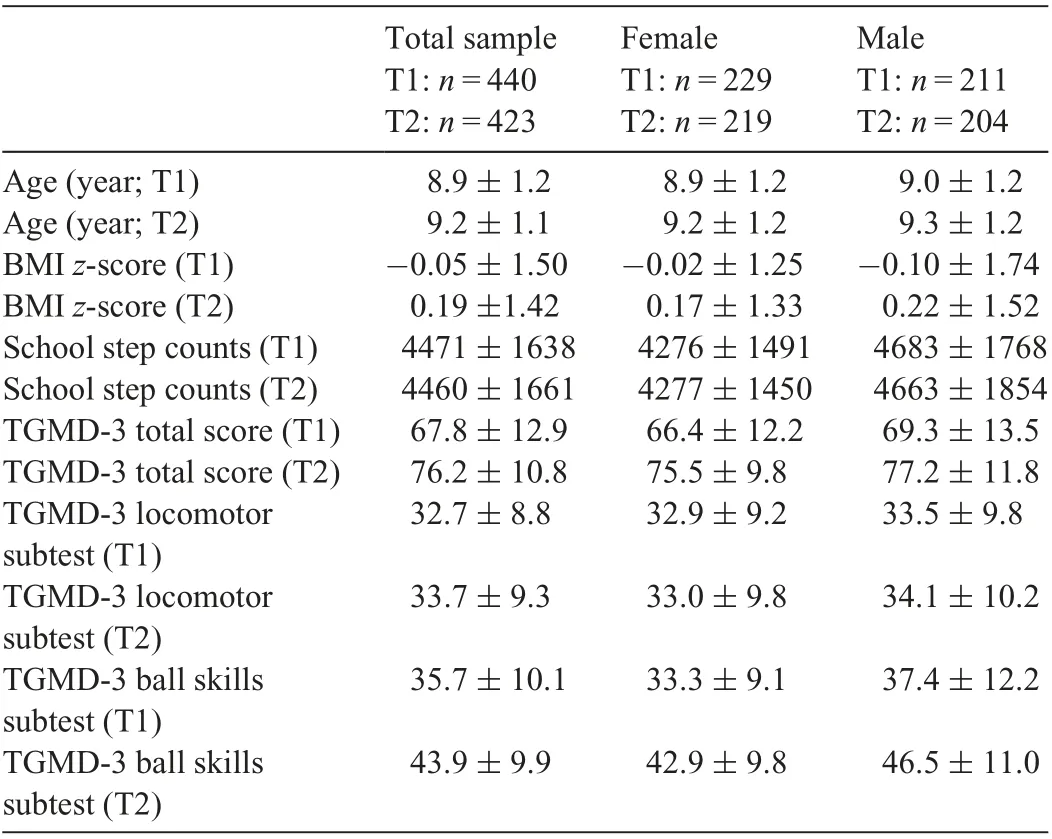

Table 1 Descriptive statistics(mean±SD).

Fig.1 presents the results of the age-and BMI-adjusted cross-lagged model using the total sample(BIC=7056.1;AIC=6991.5).T1 school steps significantly correlated with T1 gross motor skills(p=0.009);however,T2 school steps did not significantly correlate with T2 gross motor skills(p=0.871).T1 school steps significantly predicted T2 school steps(p<0.001),and T1 gross motor skills significantly predicted T2 gross motor skills(p<0.001).Interestingly,T1 gross motor skills significantly predicted T2 school step counts(p=0.003);however,T1 school step counts did not predict T2 gross motor skills(p=0.445).Not shown in Fig.1 are the associations of school steps and gross motor skills with T1 age.T1 age significantly and positively correlated with T1 steps(β=0.21,95%CI:0.09-0.33,p<0.001,T1 gross motor skills(β=0.39,95%CI:0.28-0.50,p<0.001)and T2 gross motor skills(β=0.24,95%CI:0.08-0.40,p=0.002)and significantly and negatively correlated with T2 steps(β=-0.19,95%CI:-0.33 to-0.05,p<0.001).Also,not shown in Fig.1 are the associations of school steps and gross motor skills with BMI z-scores.T1 BMI z-scores significantly and positively predicted only T2 BMI z-scores(β=0.70,95%CI:0.49-0.90,p<0.001)but did not correlate with other T1 predictors or predict any T2 outcomes.The model explained approximately 35.4%(R2=0.354)and 15.9%(R2=0.159)of variances of T2 gross motor skills and T2 step counts,respectively,using T1 steps,gross motor skills,age,and BMI z-scores as predictor variables.

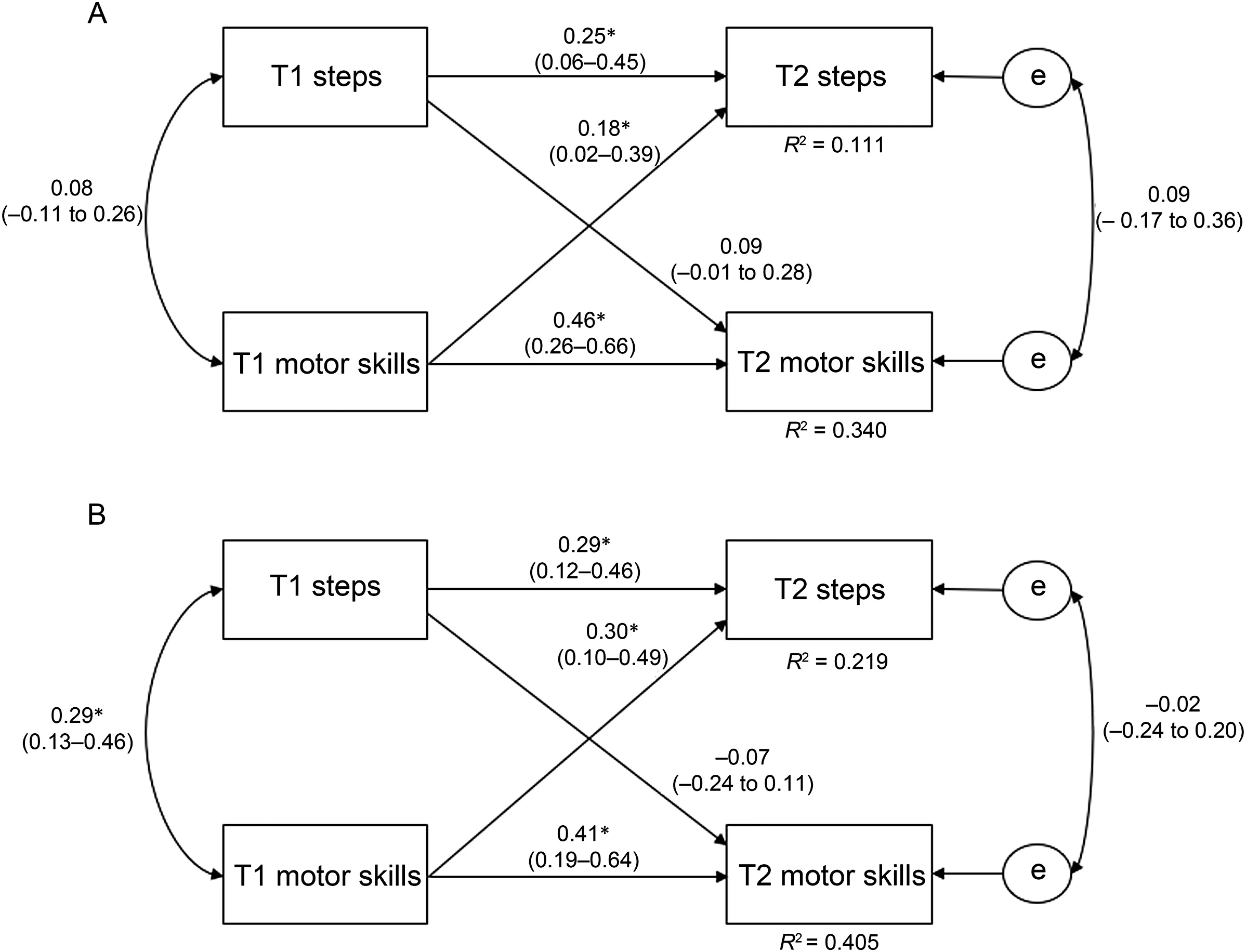

Fig.2 show sex-specific cross-lagged models for males and females,respectively (females:BIC=3295.6,AIC=3249.0;males:BIC=3804.5,AIC=3751.6).Most relationships observed using the total sample held in the sex-specific analyses,with the exception being a nonstatistically significant correlation between T1 school steps and T1 gross motor skills in males only(p=0.426).Additionally,the significant relationship between T1 gross motor skills and T2 school step counts tended to be stronger in females compared to males.The patterns of associations found for age and BMI z-scores using the total sample also held in the sex-specific analyses.The male model explained approximately 34.0%(R2=0.340)and 11.1%(R2=0.111)of the variances of T2 gross motor skills and T2 step counts,respectively;the female model explained approximately 40.5%(R2=0.405)and 21.9%(R2=0.219)of the variances of T2 gross motor skills and T2 step counts,respectively.

Additional analyses were conducted to determine whether the TGMD-3 subtest scores were associated with school step counts.Statistically significant cross-lagged paths that were found for the TGMD-3 total scores were found only for the ball-skill subtest scores,not for the locomotor subtest scores.Specifically,for the T1 gross motor skill to T2 school PA path,T1 ball skills significantly predicted T2 school step counts(β=0.20,95%CI:0.08-0.32,p<0.001);however,T1 locomotor skills did not significantly predict T2 school steps(β=0.08,95%CI:-0.19 to 0.35,p=0.783).Additionally,the statistically significant covariance found between T1 gross motor skills and T1 school steps using the TGMD-3 total scores were also found only for the ball-skills subtest scores(p<0.001),not for the locomotor subtest scores.The patterns of associations found for age and BMI z-scores using the TGMD-3 total scores also held within the TGMD-3 subtest score analyses.Therefore,the relationships found in the crosslagged models using the TGMD-3 total scores were driven primarily by variability in the ball-skill subtest scores.

Fig.2.Cross-lagged model of the bidirectional relationships between school-day step counts and gross motor skills before and after a 3-month summer break in(A)males and(B)females.Model is adjusted for T1 age,body mass index z-scores,and clustering of students within classrooms at T1.T1 stands for timepoint 1-before summer break;T2 stands for timepoint 2-after summer break;e stands for error.Path coefficients are standardized with 95%confidence intervals.*denotes a statistically significant path coefficient,p<0.01.

4.Discussion

In our study,we examined bidirectional relationships between school PA and gross motor skills over a 3-month summer break in a sample of children from low-income families using an age-adjusted,cross-lagged panel design.To our knowledge,this is the first study to examine reciprocal relationships between school PA and gross motor skills before and after a prolonged school break.The results indicated that gross motor skills,specifically ball skills,before summer break significantly predicted school PA after summer break.However,there was no evidence for bidirectionality in this relationship,as school PA before summer break did not significantly predict gross motor skills after summer break.The relationships found using the total sample generally held within sex-specific stratified analyses,although the strength of the relationships tended to be stronger in females.In the following section,we provide an interpretation of the findings,a discussion of potential practical applications,and recommended future research directions.

Previous studies have shown that the summer break can be a barrier to children’s engagement in positive health behaviors.30-35Despite a number of studies examining health behaviors,health outcomes,and health-related fitness before,during,and after summer break,30-35,45,46no studies have examined gross motor skills and their potential causal relationship with salient health behaviors such as school PA before and after summer break.One of the key findings in our study was the lack of bidirectionality between school PA and gross motor skills(i.e.,school PA did not predict gross motor skills);however,this finding aligns well with Stodden’s conceptual model.24Stodden’s model24postulates that the predictive and directional relationship between PA and gross motor skills is prevalent primarily in early childhood(before 6 years of age).In early childhood,higher PA may facilitate development of the neuromuscular system,which is needed for the development of gross motor skills.24During middle and late childhood,the proposed directionality of this relationship shifts,because gross motor skills tend to be a stronger predictor of PA,rather than PA predicting gross motor skills.Proposed reasons for this shift in directionality include the notion that older children lacking motor competency may not want to demonstrate low motor competency to their peers by engaging in PA and that these children may also have fewer movement options and PA opportunities because of the real or perceived lack of skill.24Indeed,Barnett et al.,47using a sample of elementary school-aged children,specified that children with higher levels of object-control skills tended to have higher PA levels during adolescence.The sample in our study also consisted of children who were characterized as being in middle and late childhood,and it is during this developmental age range(rather than during early childhood)when gross motor skills are postulated to have a stronger predictive relationship with PA,rather than PA predicting gross motor skills.24In our study,this directional and potentially causal relationship holds in children from low-income families from before to after a 3-month summer break,suggesting that higher ball skills may be an important antecedent for higher school PA after a prolonged summer break.It should be of note,however,that ball skills significantly improved after summer break compared to before summer break in this sample of children.At the spring timepoint(T1),there may have been many children within the sample who did not reach motor competency for ball skills,signifying a need for improvement in these skills.Reasoning for the significant improvement in ball skills over summer break may be due to increases in physical maturation or greater familiarity with TGMD-3 testing.Because physical maturation and the control for testing was not accounted for in our analyses,the observed results should be interpreted with caution.

Another interesting finding in our study was that the observed significant relationship between gross motor skills and school PA,although present in both sexes,was stronger in girls than in boys.Previous longitudinal studies have shown that girls tend to have lower gross motor skills,particularly object control/ball skills,compared to boys.48Additionally,girls tend to display less improvement in motor skills between the ages of 6 years and 9 years compared to boys.49In our study,there were nonsignificant trends for boys to score higher on the TGMD-3 compared to girls.These studies suggest a greater need for the improvement of ball skills in girls during elementary school compared to boys.Because of these sex differences in ball skills,the declines in PA throughout elementary school,and generally lower PA found in girls compared to boys,6-8the predictive relationship between gross motor skills and school PA from before to after summer break manifests itself in important practical implications for physical and health educators—specifically,to focus on ball-skill development in girls so as to sustain higher levels of PA throughout childhood.There are also important practical implications for PA researchers aiming to develop and test health-behavior interventions specifically tailored to a child’s age and sex.

Results from our study can inform future interventions designed to sustain higher levels of school PA after a prolonged summer break.Physical and health educators should continue to emphasize the importance of gross motor skills in children and communicate to students how gross motor skills can facilitate participation in a variety of PA modalities.50Children who are less motor competent and who participate in activities involving complex upper and lower body movements during sport,physical education,or leisure physical activities may not compete adequately with their counterparts who are more competent in motor skills,which may lead to lower PA enjoyment,perceived competence,and eventual disengagement from participation by those with less motor competence.51-54This ultimately may negatively affect health-related fitness and negatively affect health risk.Because the predictive relationships in our study were stronger among females than among males,targeting female gross motor skills may be especially beneficial when also considering that girls have lower average perceived physical competence and PA enjoyment than do boys.53,54However,methods for developing and testing such programs is an important area for future research.

Gross motor skill interventions have been implemented in recent years with modest success by using a number of targeted physical,cognitive,and affect variables.55-60For instance,a 9-month Mastery Motivational Climate program that provided participant autonomy in activity choice,activity duration,and choosing activity peers significantly improved preschool children’s gross motor skills.59Creating a noncompetitive and positive environment where children work together and also have a choice in engaging in various activities that will improve their gross motor skills—specifically,their ball skills—may be a good strategy for future interventions.59,60Given Stodden’s conceptual model,24frequently providing PA opportunities to children during early childhood(i.e.,3-5 years old)will help to develop their motor competency,which will subsequently serve to facilitate further PA participation during middle to late childhood(i.e.,6-13 years old).The results of our study support this potential relationship between gross motor skills and school PA before and after summer break,a period during which there may be greater barriers to sustaining positive health behaviors in children from low-income families.

Our study has several strengths,including the use of objective assessments of PA and gross motor skills,the assessment of PA and gross motor skills both before and after summer break,the use of a cross-lagged panel model to examine reciprocal relationships,and a relatively large sample size of children from low-income families.However,there are some limitations to this study that should be considered before deciding whether the results can be generalized.First,the generalizability of this study may be limited because participants were a convenience sample from 1 geographic location in the United States.Second,gross motor skills and step counts were assessed only before and after summer break,not during summer break.Future research should examine these relationships using additional timepoints during the summer to find a better representation of the trends among the different variables.Third,although step counts can be used as an assessment of ambulatory PA,only school step counts were assessed.Because children are sedentary for most of the school day,61examining the relationship between gross motor skills and total PA per day may yield more important information regarding the relationship between motor skill and PA because other factors such as school policy were not controlled for in this study.Future research examining these relationships should assess PA across the entire day by using objective and valid assessment instruments such as accelerometry and more meaningful assessment metrics such as estimated energy expenditure.Additionally,body composition was assessed using BMI,which does not distinguish between fat mass and fat-free mass and was recently shown to be a poor predictor of adiposity in children.62Future research should employ more direct measures of adiposity to improve the validity of body composition assessment.The use of the general cross-lagged panel model,which accounts for fixed differences between individuals by using a modeled latent variable,provides better evidence for causal effects over a greater number of observed timepoints.63,64There could be mediators in the relationship between PA and gross motor skills.Testing the bidirectionality of PA and gross motor skills over a summer break by using different mediator variables,such as perceived competence or specific health-related fitness test scores,could help to further elucidate potential causal mechanisms.Finally,because PA is itself associated with a number of health outcomes and other health behaviors,65,66gross motor skills predicting school PA after a prolonged summer break may have other positive effects not examined in our study,such as improved healthrelated fitness,improved sleep on school nights,and improved psychosocial measures,such as perceived competence and enjoyment of PA.67,68Therefore,the significant association between gross motor skills and school PA found in our study suggests a need for future research examining the relationship of gross motor skills with other health-related behaviors.

5.Conclusion

Children’s gross motor skills,specifically ball skills,before a 3-month summer break significantly predicted children’s school PA after summer break.To our knowledge,this is the first study to examine bidirectional relationships between gross motor skills and school PA before and after summer break.It is recommended that future research determine whether higher gross motor skills at the end of the school year can sustain PA both during and after summer break in children from low-income families.Although mediators of the relationship between gross motor skills and school PA were not tested,they should,nonetheless,be a priority for future research in order to further understand the potential causal mechanisms between the 2 constructs.Our study adds to the continually growing body of evidence concerning the important role that gross motor skills—specifically,ball skills—play within the pediatric population in sustaining PA after a prolonged summer break.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the students who participated in this study.This work was supported by a Physical Education Program Grant(Grand No.S215F140118)from the U.S.Department of Education.The study sponsor did not have any role in the study design;in the collection,analysis and interpretation of data;in the writing of the report;or in the decision to submit the article for publication.

Authors’contributions

RDB conceived the study,collected data,performed the data analysis,and drafted the manuscript;YBperformed the data analysis and drafted the manuscript;WB performed the data analysis and drafted the manuscript;TEC interpreted the results and drafted the manuscript;CDP interpreted the results and drafted the manuscript;SK interpreted the results and drafted the manuscript;TAB provided administrative support,collected data,and drafted the manuscript.All authors have read and approved the final version of the manuscript,and agree with the order of presentation of the authors.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Journal of Sport and Health Science2022年2期

Journal of Sport and Health Science2022年2期

- Journal of Sport and Health Science的其它文章

- Exercise is medicine for type 2 diabetes:An interview with Dr.Sheri R.Colberg

- Application of e-health programs in physical activity and health promotion

- Exercise cardiac power and the risk of heart failure in men:A population-based follow-up study

- A physically active lifestyle is related to a lower level of skin autofluorescence in a large population with chronic-disease(LifeLines cohort)

- Movement behaviors and their association with depressive symptoms in Brazilian adolescents:A cross-sectional study

- Using compositional data analysis to explore accumulation of sedentary behavior,physical activity and youth health